THE GREAT FREEZE is upon us.

. . .

I am still grieving1 deeply for my friend George Johnson, and since his death last Whitsun another friend – the mathematician John Collins, Fellow of the Royal Society – has also died. Their deaths have discomposed me and left me lethargic. But I begin to consider my own mortality, and am resolved to send Mr Wood all my poor scribbles by Easter term. I hope he will have the goodness to pardon and pity my melancholy and long silence.

. . .

I am ordering2 and revising my manuscripts. Since 1669 I have been reflecting on education. I have hundreds of notes on the design of a school for gentlemen and have taken one of my epigraphs for my Idea of Education from Seneca’s Epistulae Morales.

Mr Paschall urges me3 to go on with my design. He says he believes this is the great thing the world needs and it would be worth the while of a good angel to come down from heaven to promote such work.

My mind turns back to the school days I shared with George Johnson in Blandford. Plato says that the education of children is the foundation of government. It follows then that the education of the nobility must be the pillars and ornament of government: they bear the weight of it, like Atlas. But while there is ample provision in both our universities for the education of divines and clerks, no care has been taken for the right breeding of gentlemen of quality, which could not be of greater importance in a nation, since they are the root and source of a good administration of justice. It may seem paradoxical, but no nobleman’s son in England is so well bred as the King’s Mathematical Boys at Christchurch Hospital in London, which our King Charles, founded in 1673 for producing navigators. Arithmetic and geometry are the keys that open to us mathematical and philosophical knowledge, and all other knowledge as a consequence. Arithmetic and geometry teach us to reason right and carefully and not to conclude hastily or make a false step.

Without doubt4 it was a great advantage to the learned Mr William Oughtred’s natural parts that his father taught him common arithmetic perfectly while he was a schoolboy. The like advantage may be supposed of the learned Edward Davenant, whose father taught him arithmetic when a schoolboy. The like may be said of Sir Christopher Wren, Mr Edmund Halley and Mr Thomas Axe. In some men it makes no matter if they learn in later life, e.g. Mr Hobbes was forty years old, or more, when he began to study Euclid’s Elements. But more commonly, learning arithmetic after a good number of years is difficult: ’tis as if a man of thirty or forty should learn to play on the lute when the joints of his fingers are knit: there may be something analogous to this in the brain and understanding.

A banker5 in Lombard Street assured me that most tradesmen are ruined for want of skill in arithmetic. For the merchants sell to them by wholesale and the retailers (through ignorance) over shoot themselves and do not make their money again.

. . .

William Brouncker6, President of the Royal Society for about fifteen years, was buried today in the vault he had built in St Katharine’s, near the Tower of London (the vault is eight foot long, four foot broad, and about four foot high). He died on 4th of this month. He was governor of St Katharine’s and shortly before his death he gave the church a fine organ. He told me he lived in Oxford when it was a garrison for our late King, but was not of the University. Instead he addicted himself to the study of mathematics, at which he was a great artist.

Sir William Petty’s7 thirty-two questions for the trial of mineral water have been printed in the Royal Society’s Philosophical Transactions. I will include them all in my Natural History of Wiltshire, where I take notice of the springs in that county:

. . .

I am beset8 by the fear that my two volumes of notes on the antiquities of Wiltshire, which I sent to Mr Wood via his friend Mr Allan, have been lost, since I hear that Mr Allan has now died of smallpox! Last week my Natural History of Wiltshire reached Mr Paschall, but when it arrived the box was all broken to splinters and it had been months in transit. Thus we see how manuscripts are apt to be lost!

. . .

This evening I was eyewitness to one of my ever-honoured friend Mr Edmund Wylde’s experiments. Just before we sat down to dinner this evening, he sowed in an earthen porringer of prepared earth seeds of parsley, purslane, balm, etc. The porringer was then set on a chafing dish of coals and by the time we had finished dinner (about an hour and a half later) the seeds had sprung up visibly: nineteen or twenty young plants. More appeared afterwards, their leaves as big as pinheads. We drew out some of them with pliers and found the roots were about half an inch long. The dish was put out in the garden overnight. It is raining very hard now. Quaere: if the plants will survive?

. . .

Mr Paschall has written9 me a long and generous letter about my Idea of Education, which he has read through carefully. He thinks that it might be wise to make no mention of particular schools and universities, particularly not of their defects. He urges me to give some thought to educational proposals for the first nine or thirteen years, whereas at present my scheme only covers education after these years. He is particularly concerned that I should add a scheme for moral, legal and religious education.

. . .

The great stone10 at Avebury has fallen and broken into two or three pieces (it was but two foot deep in the earth!). The attorney Walter Sloper of Winterbourne Monkton (the next village north of Avebury) has let me know this. I must go to Avebury and see it if I can.

. . .

I dined tonight with Mr Wood, who came up to London last Friday (17 October). He paid for our meal.

. . .

I have asked my friend11 Mr Paschall to be sure to send some berries of the Holy Thorn of Glastonbury to my mother this Christmas. (The old tree was cut down in the late wars, but by grafting and inoculation it was preserved for the country.) Mr Paschall tells me that recently labourers at Glastonbury found a manuscript indicating treasure nearby, and a search was carried out. A man who obtained stone from a renter of the abbey found gold in it. The gold came from chimney stones, where it was perhaps hidden at the time of the Dissolution.

. . .

Dr Plot has printed a small treatise on the origin of springs, De Origine Fontium, which he has dedicated to Mr Ashmole. He has finished his natural history of Staffordshire and I hope he will turn now to Wiltshire. I asked him to undertake this work in 1675, and offered him all my papers and assistance to this end. But Dr Plot says he is too busy at the museum and will not meddle any more in work of this kind unless for his native county of Kent. He urges me to finish and publish the work on Wiltshire I began almost thirty years ago. I fear that if I do not do this myself, my papers will perish or be sold in an auction, or somebody else will put their name to my work.

I related12 to the Royal Society Colonel John Windham’s observation about the height of the barometer in Salisbury Cathedral. That steeple is 404 foot high; the weather door is 4,280 inches and at that height the mercury subsides 42/100 of an inch.

. . .

Mr Wood tells me13 he has lately heard that most, if not all, of the library at Wilton House is to be sold. I remember the books I read in that library, especially Sir Philip Sidney’s translation of the Psalms. No one knows that library better than my friend Christopher Wase, who was a tutor at Wilton. I must ask him for more information about it.

. . .

On this day the King suffered a sudden apoplectic fit.

. . .

On this day the King died at Whitehall Palace. His brother James, the Roman Catholic Duke of York, has succeeded him.

. . .

The dead King’s body was buried today in Westminster Abbey, without any manner of pomp. James II of England is our new King.

. . .

Today I saw the coronation of King James II. I watched the procession. After the King was crowned, according to ancient custom, the peers went to the throne to kiss him. The crown was nearly kissed off his head. An earl set it right, but as the King left the abbey for Westminster Hall, the crown tottered extremely.

Just as the King14 came into Westminster Hall, the canopy of golden cloth carried over his head by the wardens of the Cinq Ports was torn by a puff of wind (it was a windy day). I saw the cloth hang down very lamentably. Perhaps this is an ill omen. Storm clouds of religious strife are gathering.

. . .

Tonight stately fireworks15 were prepared on the banks of the Thames to celebrate the coronation of the King. But they all took fire together and the flames were so dreadful that several of the spectators leaped into the river, preferring to be drowned than burnt.

. . .

King James has ordered the trial of Titus Oates on charges of perjury.

. . .

Titus Oates has come16 before Judge Jeffreys and been found guilty of false testimony, on account of which many innocent Roman Catholics were arrested and some executed. He has been sentenced to be stripped of his clerical habit, to be pilloried in Palace Yard, to be led round Westminster Hall with an inscription declaring his infamy over his head, to be pilloried again in front of the Royal Exchange, to be whipped from Aldgate to Newgate, and, after an interval of two days, to be whipped from Newgate to Tyburn. If, against all probability, he survives this punishment, he is to be kept a prisoner for life, brought forth from his dungeon five times a year and exposed on the pillory in different parts of London.

. . .

My honoured friend Sir James Long has promised to send me cloth for a new suit and four cheeses from Draycot. Wiltshire is good for cloth and cheese.

I have nearly finished17 my revisions to my Natural History of Wiltshire. It is now fifteen years since I left Wiltshire, but I spent so long travelling between north and south Wiltshire on the road from Easton Pierse to Broad Chalke that I have a strong enough image of it in my mind to make some additions to my old notes even at this distance. My discourse on Wiltshire is like the portrait of Dr Kettell of Trinity College that Mr Edward Bathurst (one of Ralph Bathurst’s brothers) painted some years after his death. It was not done from life, but it did well resemble him. If I had had the leisure I would have willingly searched the whole county for natural remarks.

I hope hereafter my work will be an incitement to some ingenious and public-spirited young Wiltshire man to polish and complete what I have delivered rough-hewn, for I have not leisure to heighten my style. I will dedicate my Natural History of Wiltshire to my patron Lord Pembroke. He is hard in his bargaining but as just a paymaster as lives.

. . .

I need to move18 my mother from Bridgwater, where she has been living of late, back to Broad Chalke, and will need to spend time helping her settle. Mr Paschall and his wife will be sad at parting from her. They have been good neighbours and friends to her in Bridgwater.

. . .

There is a hill19 in Wiltshire under which three streams rise: one runs to Sarum, then on to Christ Church and into the French sea; another runs to Marlborough and on to Reading, where it runs into the Thames; and a third runs to Calne and on until it disgorges into the Avon which runs to Bristol.

It seems to me20 that the city of Bristol very well deserves the pains of some antiquary (Gloucester too). I think the best-built churches of any city in England are in Bristol, excepting the London churches that have been built since the Great Conflagration. Bristol had a great many religious houses in the old days; the Priory of Augustine is a very good building, especially the gatehouse. I think Bristol is the second city in England both for greatness and trade, and yet is not so much as mentioned in Antonini Itinerario.

Yesterday I came21 to Chedzoy, near Bridgwater, to meet Mr Paschall’s friend who is rector here. They have a scheme afoot to operate some lead mines in the Mendips – I thought perhaps this scheme might mend my fortunes. But alas! More menacing plots and plotters thwart me. I arrived here on the very night the Duke of Monmouth, the late King’s bastard son, landed at Lyme Regis to begin his rebellion. Monmouth’s soldiers entered the house and came into my chamber as I lay in bed. They took away horses and arms.

. . .

After his landing at Lyme Regis, the Duke of Monmouth collected a following of 3,000 men and was proclaimed King at Taunton. From there he went to Bristol, but the city shut its gates on him, so he retired to Bridgwater. Government forces were encamped nearby at Sedgemoor. There was fierce battle on the evening of 5 July, after which Monmouth fled. He was captured on Shag Heath and is now being held at the house of my old friend Anthony Ettrick (Recorder and Magistrate of Poole and Wimborne), from whence he will be sent to trial. Deo Gratias that storm cloud is over-blown!

. . .

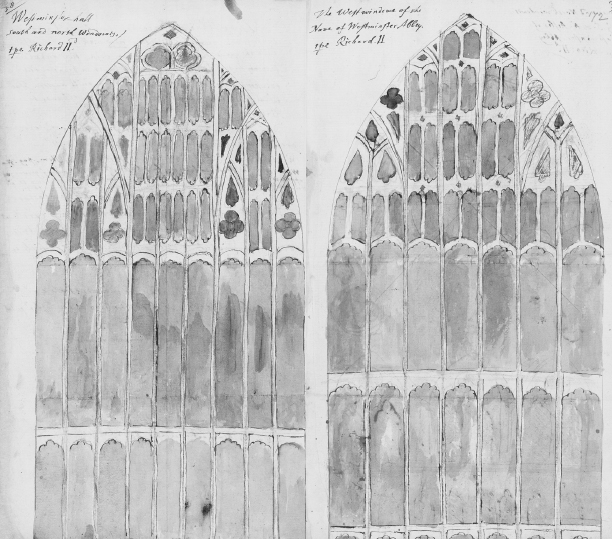

I hope to find out22 from Sir William Dugdale when glass painting was first used in England.

I have heard23 William Dugdale say that although Mr Camden has the better reputation, the antiquary Mr Robert Glover was the best Herald of the College of Arms. He took a great deal of pains in searching out the antiquities of several counties, participating in heraldic visitations in the north of England especially.

. . .

I have quarrelled furiously with my tiger brother William over money.

I cannot read24 or write for grief! I cannot go to Salisbury to search out answers to Mr Wood’s questions. My brother and I are at such a difference that it completely distracts my mind.

. . .

John Pell25 has died. I could not persuade him to make a will, so his books and manuscripts have fallen into the hands of his son-in-law.

. . .

I have visited26 Dr Pell’s last home and rescued some letters in his own handwriting from the pies! I cannot bear to think how many letters of ingenious men have been lost at the hands of cooks who value them not.

. . .

I am back now27 in the city from Broad Chalke, thank goodness, since my domestic troubles there are so great that I could not read or write this past six weeks, and could find no time to visit Salisbury to answer Mr Wood’s questions, which I would otherwise have willingly done! My tiger brother William and I have such great differences that I believe we will never be close again. I do not know if I shall ever shake off this grief.

. . .

Captain Poyntz28 has made me a grant of a thousand acres of land on the island of Tobago, for services I have done him with regard to the Earl of Pembroke and the Earl of Abingdon. He advises me to send over people to settle and to get subscribers to sign up for a share of this land, since he says 200 acres will be enough for me personally.

. . .

I have started composing29 a list of ideas for rescuing my fortunes.

– Obtain a patent to open the passage to make it wider for ships to come to Bristol, whereas now they come no nearer than Hungerode. Also to blow up the little island, or collection of rocks, in the key (called the Lidds?) at Bristol which occupies the room of two or three barks. Also to make obtuse the sharp angular rock at St Vincent’s which is a great nuisance to the merchants.

– Put somebody on to merging the Thames and Avon, and get a share in it.

– Obtain a patent to dig for the coal that I have discovered in Slyfiend Common in Surrey, near Guilford.

– Discover and find out the lands concealed and embezzled by the Fishmongers’ Company, which was to maintain so many scholars in Oxford and for the ease of poor Roman Catholics in Lent. Mr Fabian Philips tells me I may find out the donation in Stow’s Survey of London. Edmund Wylde says that the old Parliament intended to have an inspection into charitable uses.

– My discovery of the nitrous springs at Minty in Wiltshire called the Gogges (1665), where there is good fuller’s earth. I will engage Sir Edward Hungerford to help me get the ground from our friend George Pitt, Esq.

– It would be a prudent way of laying out money to build a handsome commercial house of entertainment for the water-drinkers at Seend and to make a fine bowling green etc.

– William Penn, Lord Proprietor of Pennsylvania, has given me a grant of 600 acres and advises me to plant it with French Protestants.

. . .

My friend Mr Edward Lhwyd30, who is Dr Plot’s assistant at the Ashmolean and Register to the Chymical Course at the Laboratory, thanks me for my continual favours to the museum, but tells me that most people at Oxford do not yet know what it is. They simply call the whole building the Laboratory and distinguish no further. In fact, the museum consists of three principal rooms open to the public, each about fifty-six feet long and twenty-five broad. The uppermost room is called the Musaeum Ashmoleanum, and this is where rarities are shown to visitors; the middle room is the School of Natural History, where Dr Plot, who is Professor of Chemistry as well as Keeper of the Museum, lectures three times a week; the third room, in the basement, is the laboratory, for demonstrations and experiments.

. . .

Mr Loggan will draw31 a picture of me in black and white that can be engraved for my Natural History of Wiltshire when it is printed. I also desire him to draw Wilton House so that a picture of it can be included in my book.

. . .

Today I told32 the Royal Society of a series of six drawings of sea battles done by Mr Hollar: the Society hopes to obtain them.

. . .

I described to the Royal Society how Sir Jonas Moore arranged for several curious observations of the tides at London Bridge to be made by means of a rod buoyed up at the bottom by a cork, so rising and falling with the water. I think the record of these observations is in the keeping of Mr Flamstead or Captain Hanway, and I will do my best to procure them for the Society.

I also mentioned33 that the greatest tide found on the coast of England is at Chepstow Bridge. I hope Sir John Hoskyns might pursue further investigations into that tide. Captain Collins is currently engaged in a survey of the sea coast of England, so he too could communicate his observations to the Society of the tides in various ports and headlands.

. . .

My friend Mr Paschall34 writes to tell me that our country is a pleasant land! Under his influence, Chedzoy, though close to the centre of the uprising last year, provided very few recruits for the Duke of Monmouth’s army. And yet Mr Paschall is still saddened to see the common people’s folly: many of them will not believe that the King is living, or that the late Duke of Monmouth is dead.

My good mother35 is unwell and distressed by the quarrel between me and my brother William. She is close now to the end of her life and wishes she could leave us friends.

. . .

On this day my dear and ever honoured mother died; my head is a fountain of tears. My brother William has decided my mother will be buried at Kington St Michael with my father.

. . .

Aside from necessary business, I have not written a word since my great grief. I have not touched my Natural History of Wiltshire since the evening of 21 April when I heard the news of my mother’s death. Earlier that day I just finished the last chapter, rough-hewn.

I am troubled36 by the death of my mother and the financial troubles that have resulted. Chalke must now be sold.

May I live37 to publish my papers. I must make haste for I am now sixty years old.

. . .

Mr Paschall tells38 of a holy day at Bridgwater (on Tuesday, 6 July) in remembrance of last year’s deliverance from the Duke of Monmouth (bells, guns, bonfires). The people there are hoping that the King, who pardoned the rebels, will welcome this voluntary act of loyalty and gratitude.

. . .

My friend Thomas Mariett39 tells me that his deceased first wife appeared to him: he is certain that if he could tell me all the circumstances, I would believe him.

. . .

I have been reflecting on the fate of manuscripts after the death of their author, and since I intend to take a journey into the west of the country soon, I have made a new will today. If I should depart this life before I return to London, I bequeath the unfinished manuscript of my Natural History of Wiltshire to my friend Mr Hooke of Gresham College. I humbly desire him to have my sketches of the noble buildings and prospects of Wiltshire engraved by my worthy friend Mr David Loggan. I signed this will today in the presence of four witnesses, one of them Mr Francis Lodwick.

. . .

Mr Paschall has described40 to me a case of gonorrhea in a man of sixty who has led a temperated sedentary life. He asks me to ask my friends for advice. I will send him a recipe with egg white and sugar that will help.

. . .

I have given Sir William Petty the extracts I copied out of the register books of half a dozen parishes in south Wiltshire.

. . .

Today I showed41 the Royal Society a nautilus cast in the substance of the pyrites or vitriol stone: a brass colour, found in a chalk-pit.

In the Royal Society’s Philosophical Transactions for this month and last (no. 185) there is an account of the discovery of an ancient sepulchre by the River Eure at Cocherel, Rouvray, near Pacy-sur-Eure, in Normandy. Since it slightly resembles the Sanctuary at Avebury, I have inserted this account into my manuscript. I am still working on it. I will have to change the dedication since King Charles died last year. It was he who originally set me on the task of writing about Avebury, after I showed it to him in 1663. I must finish and publish if I can.

. . .

I have begun to collect records of folk customs. I find there are many connections between the customs of classical Rome and modern England.

The Britons imbibed their Gentilisme from the Romans; and as the British language has crept into corners (like Wales and Cornwall) so the remains of Gentilisme are still kept there. I do not doubt that those customs were anciently over all Britain and Gaul; but the Inundation of the Goths drove them out, together with the language.

Quaere: How comes it to pass that while the British language is so utterly lost in England, so many Roman customs yet remain? But indeed they are most northwards, and towards Wales, while the south retains but few of them.

The Gentiles would not perfectly relinquish all their idols; so they were persuaded to turn the image of Jupiter with his thunderbolt into Christus crucifixus, and Venus and Cupid into the Madonna and her Babe, which Mr Thomas Hobbes said was prudently done, in his Leviathan.

I am reminded of my friend Thomas Browne’s critique of miracles wrought by relics in his Religio medici, which first opened my understanding when I was a young man.

. . .

I am embattled42 in a lawsuit with my brother William, who plagues me with letters and running up and down to lawyers. I have had no time of late to think my own thoughts, to help Mr Wood, or to work on my Natural History of Wiltshire. I need to fulfil my promise to Mr Dugdale to make my Templa Druidum fit for publication. Perhaps I can get to Oxford for three or four days in April, to paste some notes and memoranda into my collection of Lives. Meanwhile, I must move out of my lodgings near Gresham College, where I have lived these past ten years.

. . .

I have acquainted43 Sir Thomas Langton, one of the aldermen of Bristol, with my design to remove the Lidds, and he has imparted it to the common council of the city, who kindly received it, but troubles and debts come upon me and I do not think I will be able to emerge from them to fulfil my plan for reviving my fortunes.

. . .

Sir James Long invites me to consult him about natural history. He offers good horses from Reading to get me in three hours to Hungerford and thence to Bath.

Meanwhile he writes44 to me about ferns of the district, the many deer in Auburn Chase and the plants they feed on, the kinds of fish (lampreys plentiful in flood time) and birds of the district: water fowl and sea birds especially.

. . .

My friend Mr Paschall45 tells me the Quakers do all they can in town and county to make a great show. He believes the active ruling men among them were principals in the rebellion, and owe their lives to a scarce-hoped-for mercy from the King. He fears that the Republicans who were at the bottom of the rebellion may be exerting a mischievous influence for the overthrow of the monarchy and that their joy over the indulgence is due to their hopes of overthrowing the Church of England with the help of the Roman Catholics.

Robert Barclay’s book46, System of the Quakers’ Doctrine in Latin, first appeared in English in 1678, dedicated to King Charles, now to King James. Barclay is an old, learned man, mightily valued by the Quakers. His book is common.

. . .

Today at the Royal Society47 we discussed the plant called Star of the Earth, which grows plentifully about the mills near Newmarket and Thetford. I explained that it can also be found at Broad Chalke.

. . .

Mr Dugdale has criticised48 me for putting hearsays into writing. For example: when I was a schoolboy in Blandford there was a tradition among the country people of Dorset that Cardinal Morton – Bishop of Ely, then Archbishop of Canterbury during the reign of Henry VII – was the son of a shoemaker of Bere Regis. Mr Dugdale believes such things should not be part of a written life. But if I do not collect these minute details, they will be lost for ever. I do not say they are necessarily true, only that they have been believed true and have become part of local traditions.

I am setting out now on an excursion to Yorkshire.

. . .

On a rocky mountain49 above Netherdale there is a kind of moss that also grows in Scotland. I have pressed a piece of it, together with its roots, between two sheets of paper.

. . .

In Yorkshire50 I have seen the pyramid stones called the Devil’s Arrows today, near Borough-Bridge, on the west side of the Fosse Way. They are a kind of ragstone and not much weather beaten. I did not have the right idea about this antiquity until I saw it for myself. The stones stand almost in a straight line except the one near the Three Greyhounds, which is about two and a half yards out of line with the rest. I could not see any sign of a circular trench around the monument, like that at Avebury or Stonehenge.

The crosses at Borough-Bridge and nearby villages are the highest I have ever seen. I think the early Christians must have re-used the stone from these Devil’s Arrows to save themselves the trouble of drawing new stones out of the quarries to make their crosses. This would have reduced the number of the Devil’s Arrows still in place.

In this county51, the women still kneel on the bare ground to hail the new moon every month. The moon has a greater influence on women than on men.

From Stamford to the bishopric I saw not one elm on the roads, whereas from London to Stamford there are elms in almost every hedge.

. . .

Sir Charles Snell52 has sent me my poor brother Thomas’s ill-starred horoscope, which he had refrained from sending until now lest dread of the event might have killed him. But since poor Thomas died in 1681, no harm can come of it now.

. . .

This month I have dipped my fingers in ink. I am transcribing all the British place names I can find in Sir Henry Spelman’s Villare Anglicanum (printed in 1656) and interpreting them with the help of Dr Davies’s Dictionary and some of my Welsh friends. Spelman’s book was made from Speed’s maps, but in the maps many names are false written, so Spelman has transcribed them wrongly in his book, and in addition there are some errors introduced by the printer. I began reading Spelman’s book with only the intention of picking out the small remnant of British words that escaped the fury of the Saxon conquest. But then I decided to list the hard and obsolete Saxon words too and interpret them with the help of Whelock’s Saxon Dictionary. We need to make allowances for these etymologies. There were, no doubt, several dialects in Britain, as we see there are now in England: they did not speak alike all over this great isle.

Following my Natural History53 of Wiltshire, I am tempted to write memoirs of the same kind for Gloucestershire, Herefordshire, Monmouthshire, Flintshire and Surrey. I am fearful of what will happen to my work if I die. What shall I say or do with these pretty collections? I had thought to make Mr Hooke my executor to publish them after my death, but he has so much of his own work to do that he will not be able to finish mine. I think Mr Wood would take more care than anyone else, but many of the remarks I have collected will be lost if I do not stitch them together myself.

. . .

On this day54 Sir William Petty died of a gangrenous foot caused by gout at his house in Piccadilly Street opposite St James’s Church. As soon as I can, I must visit his house and take note of the manuscripts he has in his closet. His last two printed tracts were comparisons of London and Paris. I expect to find much unprinted or unfinished work.

. . .

I have been chosen55 to serve again on the committee that audits the Royal Society’s accounts.

. . .

I am grateful to Mr Wood for remembering my great-grandfather, Dr William Aubrey, in his book. I am grateful too to his brother, who entertains me so well when I am in Oxford.

. . .

On this day King James’s son was born. He will surely be raised a Roman Catholic and succeed to the English throne ahead of his Protestant half-sister Mary, wife of William, Prince of Orange. Anti-Catholic sentiment has reached a climax and many talk of inviting Mary and William to England. It is not clear what this might achieve. Perhaps their presence would help overturn some of the King’s policies, or perhaps there could be some kind of regency.

. . .

I dined this evening56 at the Mermaid Tavern with Mr Wood and Dr Plot. He told Mr Wood that when his book is published, he would give him 5 li. for a copy. I have asked Mr Wood to give all the papers of mine that he has to the museum for safe keeping.

. . .

I have decided57 to donate to the museum in Oxford a miniature of myself by Samuel Cooper, and one of Archbishop Bancroft by Nicolas Hilliard, the famous illuminer in Queen Elizabeth’s time, together with a collection of thirty-seven coins (seven silver, the rest brass) and other things of antiquity dug up from the earth. The picture of me is done in water colour and set in a square ebony frame; that of Archbishop Bancroft is set in a round box of ivory, not much bigger than a crown piece. I have sent all these things to Mr Wood in Oxford and asked him to deliver them for me. I promised him he could peruse all that I am giving first, before passing the box and its contents to the museum.

. . .

May, June58, and July this year have been very sickly and feverish.

. . .

Dr Plot complains that Mr Wood has not yet delivered my box to the museum. He has let the museum have the two miniatures and the coins I sent, but kept back the rest together with the manuscripts of mine that are in his keeping.

. . .

New troubles arise upon me like hydras’ heads.

I am concerned59 about my papers and collections, which are still with Mr Wood. He will not surrender them to Dr Plot for the museum as I have asked. Dr Plot has told Mr Ashmole what has happened and he is outrageously angry, as Mr Wood is suspected of being a Papist, and in these tumultuous times his papers will surely be searched. My manuscripts must not fly around like butterflies.

My brother William, whom I have injured, is very violent. In our shared troubles over money, I have not always behaved well and have put my interests above his when I needed to. In my father’s will he was left a portion but it was always hard for me to pay it and lately impossible. He is keen to meet me, but I must avoid him. He writes to me often, sending his letters to me via Mr Hooke. This strife between us gravely disturbs me.

My heart is almost broke and I have much ado to keep my poor spirits up. I pray God will comfort me.

I am separated from my books. They are all at Mr Hooke’s or my old landlord Mr Kent’s, so even if I had any leisure to enjoy them, I could not.

To divert myself since the removal of my books, I have been perusing Ovid’s works. I have picked up a sheet or so of references for my Remaines of Gentilisme (my collection of folklore which I have been working on since February last year); some of them are from his Epistles and Amores, where one would not expect to find anything. See what a strange distracted way of studying the Fates have given me.

To rescue my finances, I need to sell my last remaining interest in Broad Chalke farm and keep an annuity of 250 li. for myself if I can. My brother William must not hear of it.

I desire of God60 Almighty nothing but for the public good.