Butler started writing science fiction at age twelve, after seeing the 1954 movie Devil Girl from Mars on television. “As I was watching this film, I had a series of revelations,” the California-born author recalled years later. “The first was that ‘Geez, I can write a better story than that.’ And then I thought, ‘Gee, anybody can write a better story than that.’ And my third thought was the clincher: ‘Somebody got paid for writing that awful story.’ So I was off and writing, and a year later I was busy submitting terrible pieces of fiction to innocent magazines.” After college, Butler worked a series of “horrible little jobs”—including as a dishwasher, a telemarketer, a warehouse worker, and a potato-chip inspector—while continuing to write in the early mornings. “I felt like an animal, just living in order to live, just surviving,” she said. “But as long as I wrote, I felt that I was living in order to do something more, something I actually cared about.” She finally published her first novel, Patternmaster, in 1976, and went on to publish a novel a year for the next four years, including one of her best-known works, 1979’s Kindred, after which she was able to support herself by her writing alone.

As she became an internationally acclaimed author, Butler was often asked for her advice to young writers. She always said that the most important thing was to write every day, whether you feel like it or not. “Screw inspiration,” she said. Butler also suggested that aspiring writers might “look at the lives of a half dozen writers to see what they do.”

That doesn’t mean that you’ll do what any of them do, but what you’ll learn from what they do is that they have felt their ways. They have found out what works for them. For instance, I get up between three or four o’clock in the morning, because that’s my best writing time. I found this out by accident, because back when I used to work for other people I didn’t have time to write during the day. I did physical work, mostly hard physical work, so I was too tired when I came in at night. I was also too full of other people. I found that I couldn’t work very well after spending a lot of time with other people. I had to have some sleep between the time that I spent with other people and the time that I did the writing, so I would get up early in the morning. I generally would get up around two o’clock in the morning, which was really very much too early. But I was ambitious, and I would write until I had to get ready to go to work.

As she got older, Butler’s schedule loosened somewhat. According to a 2000 profile in The Seattle Times, her routine was “waking between 5:30 and 6:30 a.m., taking care of things around the house, and sitting down at her computer to write at 9 a.m.” She considered herself a slow writer, and spent much of her working day “reading books or sitting and staring or listening to book tapes or music or something and then all of a sudden I’m writing furiously.” This meant lots of time on her own, which suited the “comfortably asocial” author just fine. “I enjoy people best if I can be alone much of the time,” Butler said in 1998. “I used to worry about it because my family worried about it. And I finally realized: This is the way I am. That’s that. We all have some weirdness, and this is mine.”

“I fight pain, anxiety, and fear every day, and the only method I have found that relieves my illness is to keep creating art,” the Japanese conceptual artist wrote in her 2011 autobiography, Infinity Net. Kusama has suffered from visual and aural hallucinations since she was a child, and in 1977 she checked herself into the Tokyo mental hospital where she still lives. Across the street, she built a studio where she works every day. In her autobiography, Kusama described her routine:

Life in the hospital follows a fixed schedule. I retire at nine o’clock at night and wake up the next morning in time for a blood test at seven. At ten o’clock each morning I go to my studio and work until six or seven in the evening. In the evening, I write. These days I am able to concentrate fully on my work, with the result that since moving to Tokyo I have been extremely prolific.

Indeed, as the international art world has rediscovered Kusama over the last two decades, she has had to hire a small army of assistants to help her keep up with the demand for her work—and nowadays the artist works harder than ever. “Every day I am creating a new world by making artworks,” Kusama said in 2014. “I wake up early in the morning and stay up late at night, sometimes until 3 a.m., just to make art. I am fighting for my life and don’t take any rest.”

“Some days all I do is write and then for months I don’t write a thing,” the American poet said in 1978. Bishop’s friend and fellow poet Frank Bidart confirmed that “she didn’t (so far as I know) write every day, or in any kind of regular pattern. . . . When an idea for a poem possessed her, she carried it as far as she could, and then might let the fragments lie waiting to be finished for immense lengths of time.” Between starting and finishing her poem “The Moose,” for instance, twenty years elapsed.

Bishop often felt guilty about her modest output—she published only about a hundred poems in her lifetime—and wished that she had written more. Briefly, in the early 1950s, she tried to speed along the process with stimulants. Bishop had recently moved from the United States to Brazil to be with her lover, the architect Lota de Macedo Soares. But upon settling in her new home, she discovered that her chronic asthma had grown much worse. To control it, Bishop began taking cortisone, and she found that the drug’s side effects were potentially useful for a writer—it produced sleeplessness combined with a kind of creative euphoria, which she thought could be beneficial for her poetry and for the short stories she was trying to write at the time. “To begin with it is absolutely marvelous,” Bishop reported to the poet Robert Lowell, her close friend and confidant.

You can sit up typing all night long and feel wonderful the next day. I wrote two stories in a week. The letdown isn’t bad if you do all the proper things, but once I didn’t and found myself shedding tears all day long for no reason at all. This time I’m hoping it will help me get that last impossible poem off to H. Mifflin [her publisher]. . . . Try it sometime. It seems to apply to just about anything.

The euphoria was short-lived—Bishop soon grew afraid of the drug’s effect on her emotions and stopped taking it. Over time, she seemed to reconcile herself to her halting, gradual work style. She liked to quote Paul Valéry: “A poem is never finished, only abandoned.”

The German choreographer expanded the possibilities of modern dance by incorporating dreamlike sequences, elaborate stage sets, dramatic speeches, and snatches of dialogue into her hugely influential “dance theater.” Famously, from the late 1970s on, she developed her pieces through a question-and-answer process, drawing on her dancers’ memories and everyday lives as the basis for a new performance. “Pina asks questions,” one of her longtime dancers explained. “Sometimes it’s just a word or a sentence. Each of the dancers has time to think, then gets up and shows Pina his or her answer, either danced, spoken, alone, with partner, with props with everyone, whatever. Pina looks at it all, takes notes, thinks about it.” For Bausch, the questions were a way to get at ideas that she couldn’t access on her own. “The ‘questions’ are there for approaching a topic quite carefully,” she once said. “It’s a very open way of working but again a very precise one. It leads me to many things, which alone, I wouldn’t have thought about.” She was always searching for something she couldn’t easily define, “not something I know with my head exactly,” she said, “but to find the right images. And I have no words for that. But I know right away when I’ve got it.”

To people on the outside of this process, it could be daunting to watch her at work. “The anguish that she goes through is enormous,” Bausch’s partner, Ronald Kay, told The Guardian in 2002. “She comes home like a heap of ashes. I have learned to look at it from a distance. To be absolutely outside of it is the only way I can help.” Kay went on to describe Bausch’s work schedule during the rehearsals for a new performance:

She works in the rehearsal room from 10 in the morning, and rehearsals don’t end till late in the evening. She comes home at about 10 at night, we eat, and then she sits there till two or three o’clock getting an idea of what it was all about, what can be kept, what are the little jewels of the piece. And then she gets up at seven, sometimes even earlier, to prepare. She always manages to keep the same intensity.

Bausch herself struggled to explain the source of this intensity. When faced with the prospect of developing a new piece, her immediate response was closer to despair than enthusiasm. “There is no plan, no script, no music, and no set,” she said.

But there is a date for the premiere and little time. Then I think: it is no pleasure to do a piece at all. I never want to do one again. Each time it is a torture. Why am I doing it? After so many years I still haven’t learnt. With every piece I have to start from the beginning again. That’s difficult. I always have the feeling that I never achieve what I want to achieve. But no sooner has a premiere passed than I am already making new plans. Where does this power come from? Yes, discipline is important. You simply have to keep working and suddenly something emerges—something very small. I don’t know where that will lead, but it is as if someone is switching on a light. You have renewed courage to keep on working and you are excited again. Or someone does something very beautiful. And that gives you the power to keep on working so hard—but with desire. It comes from inside.

María Sol Escobar was born to a wealthy Venezuelan family, grew up in Paris and Caracas, went to high school in Los Angeles, and studied art in Paris and New York. She initially pursued painting but, in 1953, began making sculptural figurines “as a kind of rebellion,” she said. “Everything was so serious. I was very sad myself and the people I met were so depressing. I started doing something funny so that I would become happier—and it worked. I was also convinced that everyone would like my work because I had so much fun doing it. They did.” She soon adopted the name Marisol and, by the mid-1960s, was a New York art-world star, known for her witty melding of Pop and folk art, and for her enigmatic public persona. “The first girl artist with glamour,” declared Andy Warhol, who cast her in his films The Kiss and 13 Most Beautiful Women. Like Warhol, Marisol had a knack for terse pronouncements that walked a line between naïveté and profundity. “I don’t think much myself,” she said in a 1964 interview. “When I don’t think, all sorts of things come to me.”

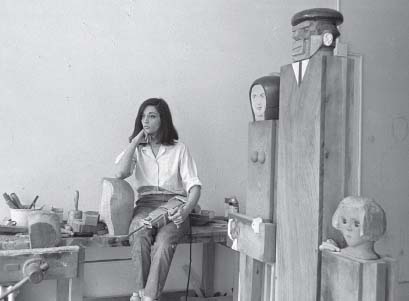

Marisol, New York, 1964

In 1965, a New York Times reporter sketched the artist’s daily routine. It began at about noon, when Marisol woke up and ate her standard breakfast of ham and eggs. Then she headed from her Murray Hill apartment to her loft on lower Broadway, stopping along the way to purchase materials—“nails, glue, chair legs, barrel staves, pine planks from a lumber yard”—while also keeping an eye out for new additions to her cherished collection of “props,” which ranged from tiny parasols to a stuffed dog’s head from a taxidermist’s. “I do my research in the Yellow Pages,” she said. Once inside her ninety-by-twenty-five-foot studio, Marisol began working with a mix of carpentry, carving, and power tools, sawing, hammering, chiseling, and sanding her sculptures into existence. She continued until the evening, when, most nights, she headed uptown for gallery openings or parties, often escorted by Warhol. She ate a late dinner and frequently returned to work afterward. “Her discipline is iron,” the painter Ruth Kligman said. “Sometimes I’ve passed her studio at 2 a.m. and seen her there still plugging away.”

At openings and parties, Marisol was notorious for her silences; many friends and acquaintances recalled spending hours with the artist without her uttering a word. According to the critic John Gruen, “When Marisol was quiet she could sit in a chair for hours without moving a muscle.” In his memoir of the New York art world in the 1950s, Gruen describes an outdoor lunch on Long Island that Marisol attended along with a number of other artists and musicians:

Marisol was listening to the lively conversation around the table. Silent as a statue, she sat totally still for at least two hours. At one point I turned toward her and noticed, to my astonishment, that a spider had spun a complete web, filling in the triangle formed by her bare upper arm, her torso, and her armpit. When I pointed this out to her—and to the rest of the company—Marisol calmly glanced at the spider and its work, saying, “The same thing happened to me once in Venezuela. It’s nothing new to me. I’m used to it.”

Although this extreme reticence could seem like an act, Marisol’s friends swore that it was genuine. In 1965, a friend defended her behavior to The New York Times: “A, she’s genuinely shy. B, she realizes that most people have nothing much to say. So why should she put out more energy than she has to? She saves it for work. When she does say something, it’s direct and to the point. She puts things in their place.”

For her part, Marisol claimed not to understand—or care about—all the attention devoted to her public persona. “I don’t feel like a myth,” she said in the 1970s. “I spend most of my time in my studio.” As for her years of relentlessly making the rounds of parties—she went to those things “to relax,” she said. “Because it’s very depressing to be so profound all day.”

In her autobiography, I Put a Spell on You, Simone compared her best performances to a bullfight she once witnessed in Barcelona, a shocking display of violence that touched something deep in the audience and left them feeling transformed. Onstage, Simone felt that she occupied a role similar to that of the toreador—and, she wrote, “people came to see me because they knew I was playing close to the edge and one day I might fail.”

But getting audiences to experience something profound was also a matter of technique, and Simone honed her methods over years of touring:

To cast the spell over an audience I would start with a song to create a certain mood which I carried into the next song and then on through into the third, until I created a certain climax of feeling and by then they would be hypnotized. To check, I’d stop and do nothing for a moment and I’d hear absolute silence: I’d got them. It was always an uncanny moment. It was as if there was a power source somewhere that we all plugged into, and the bigger the audience the easier it was—as if each person supplied a certain amount of the power. As I moved on from clubs into bigger halls I learned to prepare myself thoroughly: I’d go to the empty hall in the afternoon and walk around to see where the people were sitting, how close they’d be to me at the front and how far away at the back, whether the seats got closer together or further apart, how big the stage was, how the lights were positioned, where the microphones were going to hit—everything. . . . So by the time I got on stage I knew exactly what I was doing.

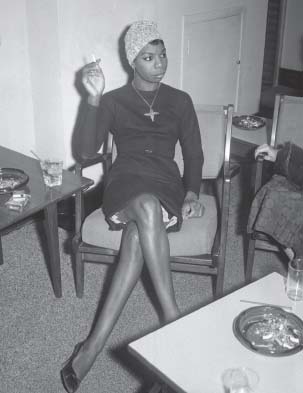

Nina Simone, Pittsburgh, 1965

Before important concerts, Simone would practice alone for hours at a time, sometimes playing the piano for so long that her arms “would seize up completely.” She made sure her band was just as rigorously prepared; she rehearsed every detail of the show with them, and she made an effort to gather musicians around her who understood and empathized with the particular experience she was trying to create. On concert nights, Simone didn’t give the band a set list until the very last minute, sometimes right as they were walking out onstage; before she chose the songs, she wanted to soak up the mood of the audience and the venue for as long as possible. When she walked out, she was “super-sensitive” to the crowd, and yet at the same time she tried to play for herself alone and draw the audience into what she was feeling. Even with all this preparation, however, Simone could never predict when a given show would make the leap from a solid professional performance to something strange and sublime. “Whatever it was that happened out there under the lights,” she wrote, “it mostly came from God, and I was just a place along the line He was moving on.”

A photograph, Arbus said, “is a secret about a secret.” And Arbus loved secrets. “I can find out anything,” she once said. She took up photography, in part, because she thought of it as “a sort of naughty thing to do” and “very perverse.” Throughout her career, Arbus almost exclusively shot portraits, on commission for magazines like Harper’s Bazaar, Esquire, and New York, and on her own time, cruising parks, circuses, freak shows, nudist colonies, society balls, swinger parties, and psychiatric institutions for new subjects. Her favorite people to shoot were outsiders and misfits, especially the more subtle varieties. Beatniks and hippies bored her; she preferred people who couldn’t help being a little off-center, and the thrill was getting them to reveal something of their inner self to the camera.

To make this happen, Arbus played a waiting game. Arriving for a shoot, often inside the subject’s home, Arbus would be reserved and soft-spoken but friendly, not at all bossy or demanding. Gently, she would ask her subjects to move about until they arrived at a pose that she liked; then, Arbus would ask them to hold the pose for fifteen or twenty minutes—a long time for anyone to hold a single pose, especially the nonprofessional models who were Arbus’s usual subjects. Finally, Arbus would allow them a short break, only to ask them to resume the same pose for another fifteen minutes. She would keep this up for hours, far longer than her subjects expected, and far beyond most people’s ability to remain poised in front of the camera. “She would try to wear people down,” said the photographer Deborah Turbeville, who worked with Arbus on Harper’s Bazaar assignments in the mid-1960s. “They just stood there looking wilted.” (Turbeville and her assistant would sometimes covertly remove rolls of film from Arbus’s camera bag to bring the shoot to an end sooner.) But Arbus needed the shoots to drag on, both because she wanted her subjects to drop their guard and because she sought a particular kind of connection with them. As Turbeville explained, “It was an endurance process, while she tried to get herself excited and then to get a response from [the subjects]. She would ask them questions. She would reveal something about herself and hope these people would react and then she would go from there and get more and more intimate until she’d slam a home run.”

It was similar to the kind of charge that Arbus sought out in her sex life, which was unusually vigorous, even by the standards of the sexual revolution. Arbus frequently slept with her photographic subjects, and she told one confidant that she had never in her life turned down anyone who asked her to bed. According to the biographer Arthur Lubow, when Arbus started seeing a psychiatrist in the late 1960s, she “described going up to strangers on the street and propositioning them for sex. She spoke of answering ads in swinger magazines and bedding physically unattractive couples. She recounted sexual escapades on Greyhound buses and at orgies. She detailed episodes of sexual intercourse with sailors, women, nudists. . . . Most startling of all, she said in an offhand way that she slept with her brother, Howard, whenever he came to New York.”

The therapist was perturbed, but Arbus could never explain her own impulses, in art or in life, and she wasn’t very interested in trying. “I photograph, I can’t even really figure out what the reason is,” she once said. “I don’t know what else to do. It became a thing, really, that the more I did it the more I could do it.” The closest she came to clarifying her artistic motivations was in answer to a question about how she chose her subjects. Arbus said, “I do what gnaws at me.”