The Russian-born American sculptor possessed all the usual traits of the prolific: intense drive, large stores of physical energy, and a powerful need to prove her worth to the world. But, she said, “I’m also prolific because I know how to use time.” In her autobiography, Nevelson described her daily routine:

I get up, six in the morning. And I wear cotton clothes so that I can sleep in them or I can work in them—I don’t want to waste time. I go to the studio, and usually I put in pretty much of a big day. And very often, almost all the time (I think I have a strong body), it wears me out. The physical body is worn out before the creative. When I finish, I come in and go to sleep if I’m tired, have something to eat. . . .

Sometimes I could work two, three days and not sleep and I didn’t pay any attention to food, because . . . a can of sardines and a cup of tea and a piece of stale bread seemed awfully good to me. You know, I don’t care about food and my diet has very little variety. I read once that in her old age Isak Dinesen only ate oysters and drank champagne, and I thought what an intelligent solution to ridding oneself of meaningless decision-making.

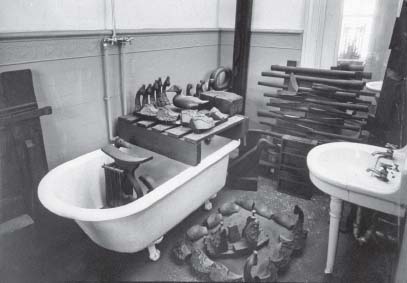

Louise Nevelson’s bathtub, 1958

Nevelson gave this account in 1976, when she was seventy-seven years old and one of the world’s most famous living artists. But before reaching this pinnacle she had toiled in near obscurity for decades. A bad marriage at eighteen, and an unplanned pregnancy the next year, derailed her early ambitions, and it took Nevelson more than a decade to escape her marriage and establish herself as an independent artist in New York. Even after that, she exhibited her work for twenty-five years without making a sale, didn’t have her first solo exhibition until she was forty-two years old, and didn’t get her big break until her work was included in a 1958 exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, when Nevelson was almost sixty.

Until then, the artist got by thanks to regular infusions of money from her family and occasional gifts from her many lovers. (She never had a day job.) Her brother, who owned a successful hotel in Maine, was especially supportive—for years he gave Nevelson a monthly allowance, and in 1945 he bought her a four-story town house on Manhattan’s East 30th Street. By then, Nevelson’s son had left home to join the merchant marine (and had also started sending his mother regular checks), and it was over the subsequent decade that Nevelson, through much experimentation, arrived at her mature style. After years of making small and medium-size sculptures from salvaged pieces of wood, she started to build massive monochrome carved-wood walls, essentially inventing the field of environmental sculpture. She later told her friend Edward Albee that she found her true identity as a sculptor when she “stood up the wood.”

As she gained confidence in her new work, Nevelson became increasingly prolific, producing about sixty sculptures a year; by the late 1950s she had filled her home with approximately nine hundred sculptures. Decades later, the New York Times art critic Hilton Kramer recalled visiting Nevelson’s town house around this time:

Nothing that one had seen in the galleries or museums or, indeed, in other artists’ studios could have prepared one for the experience that awaited a visitor to this strange house. It was certainly unlike anything one had ever seen or imagined. Its interior seemed to have been stripped of everything—not only furniture and the common comforts of daily living, but of many mundane necessities—that might divert attention from the sculptures that crowded every space, occupied every wall, and at once filled and bewildered the eye wherever it turned. Divisions between the rooms seemed to dissolve in an endless sculptural environment. When one ascended the stairs, the walls of the stairwell enclosed the visitor in this same unremitting spectacle. Not even the bathrooms were exempted from its reach. Where, I wondered, did one take a bath in this house? For the bathtubs, too, were filled with sculpture.

By all accounts, Nevelson enjoyed her late-life renown, and it was around the time of her 1958 MoMA exhibition that she began to don the outrageous wardrobe that became her signature, wearing thick eyelashes made from mink, elaborate headscarves, flowing dresses, and flamboyant jewelry. But she still spent the vast majority of her time alone in the studio. After her disastrous first marriage, Nevelson swore off that institution forever—“It’s a lot of work and it’s not that interesting,” she said of marriage—and although she had many lovers and a wide circle of friends and admirers, she kept most of them at arm’s length. As Edward Albee put it: “I imagine I was kept in my compartment like everyone else was—in my Nevelson box.”

As she grew older, Nevelson only became more devoted to her work, which after all had been the one sustaining force in her life. “I like to work,” she said. “I always did. I think there is such a thing as energy—creation overflowing. . . . In my studio I’m as happy as a cow in her stall. My studio is the only place where everything is all right.”

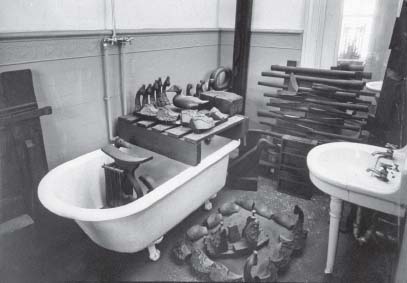

Born Karen Dinesen in Copenhagen, she became Baroness Blixen upon marrying her cousin, a Swedish nobleman, in 1914. Shortly after their engagement, the couple settled in Kenya, where they intended to run a coffee plantation. Both ventures—the marriage and the plantation—eventually failed, and in 1931 Dinesen returned to Denmark, rudderless and broke, to live with her mother. Her story might have ended there, but Dinesen had a new venture in mind. “During my last months in Africa, as it became clear to me that I could not keep the farm, I had started writing at night, to get my mind off the things which in the daytime it had gone over a hundred times, and on to a new track,” she later recalled. While still in Kenya, Dinesen had penned the first two stories of what would become her first book, Seven Gothic Tales, an unlikely best seller when it was published in 1934 under the pseudonym Isak Dinesen. She followed it with Out of Africa, the classic memoir of her seventeen years in Kenya, completing her transformation into an international literary celebrity.

Unfortunately, as her writing career was taking off, Dinesen’s health was flagging. During her marriage, Dinesen’s philandering husband had given her syphilis, and the disease would cause her considerable anguish throughout her life; the effects included impaired balance, difficulty walking, anorexia complicated by ulcers, and attacks of abdominal pain so severe that they sometimes left her lying on the floor “howling like an animal.” (Dinesen’s secretary Clara Svendsen said it was “like one human being trying to stem an avalanche.”) Dinesen’s writing habits shifted with her health. “In her late forties and early fifties,” the biographer Judith Thurman writes, “the bad days alternated with relatively long periods of good health and vigor, when she could visit her neighbors on an old bicycle and swim in the Sound before sitting down to write in the morning. But as she aged, it sapped her ability to work, to eat, to concentrate, even to sit upright, and she would dictate much of her later work to Clara Svendsen lying on the floor or confined to bed.”

Isak Dinesen, 1950s

In her later years, Dinesen famously claimed that she subsisted on a diet of oysters and champagne—but, as Thurman writes, it was actually amphetamines that “would give her the overdrive she required, and late in her life she took them recklessly, whenever strength was needed at an important moment.” Doing so hastened her death, but Dinesen was determined to live as fully as possible—and to transform her experiences into writing—until the end. She told a friend, “I promised the Devil my soul, and in return he promised me that everything I was going to experience would be turned into tales.”

“I had to succeed,” the American-born French dancer and singer once wrote. “I would never stop trying, never. A violinist had his violin, a painter his palette. All I had was myself. I was the instrument that I must care for, just as Sidney [Bechet] fussed over his clarinet.” Baker spent thirty minutes every morning rubbing herself with half a lemon in an attempt to lighten her skin—a lifelong obsession—and the same amount of time preparing a special mixture to apply to her hair. But she didn’t worry about her diet and didn’t follow any special exercise regimen, at least not in the early days of her career, when she was dancing ten hours a day or more. In Paris in the 1920s, Baker would start her evening dancing at the Folies Bergère and then make subsequent appearances at other cabarets until finally heading home at dawn “through a murky Paris preparing for work—the Paris of the poor,” she wrote. “Collapsing into bed, I would snuggle against my puppies and sleep until the maid awakened me at four.”

Baker wasn’t always able to sleep this late; for most of her life she was plagued by nightmares and insomnia, and was known to telephone friends as early as 5:30 in the morning, alert and ready to chat even after staying up most of the night. “Her secret was little catnaps,” one friend recalled. “Many times [in person] she would be talking to me and suddenly drop off to sleep in the middle of the conversation. Then, a half hour later, she would awaken abruptly, as if she had never napped, and continue on the same subject.”

Josephine Baker, circa 1925

Baker’s chronic lack of sleep, frenetic lifestyle, and outsize ambitions did seem to take their toll, however, as the dancer became prone to sudden outbursts of anger and irritation. “She was always in a crisis,” one of her employees recalled. “I never knew what started them. Sometimes there would be one per day; other times two per day or only one per week. Sometimes a crisis would last a week. They were like seizures that took hold of her.” Baker’s first husband confirmed that she fundamentally did not know how to unwind. “Friends often asked us to spend a quiet day at their hacienda,” he wrote. “Josephine would accept politely, but at the last minute would find a reason to break the engagement. There was always something else she wanted to do or see. ‘Turn off your motor, Josephine,’ I’d tease. Impossible. She simply couldn’t slow down.”

Hellman started writing drama in her late twenties and quickly vaulted into the first rank of American playwrights, a position she would occupy for the next twenty-five years. Her first play, a comedy, was never performed—but her second, The Children’s Hour, opened in 1934 and was an immediate sensation, earning its twenty-nine-year-old author $125,000 from its first run and a $50,000 contract from Hollywood to write the film version. From then until the early 1960s, Hellman produced a new play almost every other year; in between, she wrote screenplays. But the New Orleans–born writer was never comfortable with success, and after her second hit play, 1939’s The Little Foxes, she fled New York for Hardscrabble Farm, a 130-acre property about an hour and a half drive north of the city. There Hellman quit drinking (mostly), and her relationship with the writer Dashiell Hammett eased from a combative love affair to a comfortable friendship (mostly), with the two writers sharing a home base but occupying separate bedrooms and independently entertaining their own friends and lovers.

It was not always an easy arrangement, but it proved durable. Hammett had by then ceased writing—after the success of his 1934 novel The Thin Man, he never published another book—but Hellman threw herself into her work. At Hardscrabble she seemed to tap into an unlimited reservoir of energy, writing several hours a day while pursuing all manner of projects on the farm. She hired two maids, a cook, a full-time farmer, and seasonal farm helpers. She planted vegetable gardens, raised chickens and sold their eggs, swam and fished in the eight-acre lake, bred standard poodles, and hosted friends for long visits—although she expected her guests to entertain themselves most of the time. “My friends come to stay and amuse themselves any way they want to—most of them read,” Hellman told a reporter in 1941. “We meet at meals. When I write I still leave plenty of time around the meal hours; work three hours or so in the morning, two or three hours in the afternoon, and start again at 10 and work until 1 or 2 in the morning.”

Her morning routine, she said in another interview, was to get up at 6:00, make coffee, and help the farmer milk the cows or clean the barn until 8:00, then eat breakfast before settling down to write. She worked at the typewriter, chain-smoking and drinking coffee while she wrote; according to a 1946 profile, she drank twenty cups of strong coffee and smoked three packs of cigarettes a day. To prevent interruptions from her houseguests, Hellman posted a warning on the door of her study:

THIS ROOM IS USED FOR WORK

DO NOT ENTER WITHOUT KNOCKING

AFTER YOU KNOCK, WAIT FOR AN ANSWER

IF YOU GET NO ANSWER, GO AWAY AND

DON’T COME BACK

THIS MEANS EVERYBODY

THIS MEANS YOU

THIS MEANS NIGHT OR DAY

By order of the Hellman-Military-Commission-for-Playwrights.

Court-martialling will take place in the barn, and your trial will not be a fair one.

Although she worked steadily each day, Hellman’s writing progressed slowly; generally it took her a year or longer to complete a new play. In part, this was because she did extensive research before she began writing; for her 1941 play Watch on the Rhine, Hellman made digests of twenty-five books and filled her notebooks with “well over 100,000 words,” almost none of which made it into the finished work. In addition, she went through numerous drafts of each play: Watch on the Rhine required eleven rough versions and four complete drafts. As she worked, Hellman paid fanatical attention to the dialogue, reading it out loud to herself every night and again every morning before she resumed writing. She carried the projects forward on successive currents of “elation, depression, hope,” she said. “That is the exact order. Hope sets in toward nightfall. That’s when you tell yourself that you’re going to be better the next time, so help you God.”

Chanel was born in poverty, spent her adolescence in an orphanage, and received little formal education. Despite this disadvantaged start, she was a household name by age thirty and a multimillionaire by forty. Not surprisingly, work was her life, and the only truly reliable partner she ever found. Her unceasing dedication to the Chanel brand made her a formidable businesswoman—and, for her workers, a demanding and even tormenting employer. As the biographer Rhonda K. Garelick has written, Chanel’s staff at her Paris headquarters was kept in a constant state of “watchful anxiety.” Here, Garelick describes Chanel’s work routine in Paris:

While much of the staff reported to work at about eight thirty in the morning, Coco had never been an early riser and tended to show up hours later. When she did arrive, usually around one p.m., she was attended by a degree of fanfare befitting a five-star general or royal monarch. The moment Coco left her apartment across the street at the Ritz, hotel staff members would immediately telephone the operator at rue Cambon to alert her. A buzzer would sound throughout the studio to spread the word: Mademoiselle was on her way. Someone downstairs would spray a mist of Chanel No. 5 near the entrance, so that Coco could walk through a cloud of her own signature scent. . . . “When she entered the studio, everyone stood up,” recalled the photographer Willy Rizzo, “like children at school.” Then, the staff would form a line, hands at their sides, “as in the army,” employee Marie-Hélène Marouzé put it.

Coco Chanel, 1962

Once upstairs in her office, Chanel would set immediately to work on her designs. She refused to use patterns or wooden mannequins, and so would spend long hours draping and pinning fabrics on models, smoking one cigarette after another, rarely or never sitting down. According to Garelick, “She could remain standing for nine hours at a time, without pausing for a meal or a glass of water—without even a bathroom break, apparently.” She stayed until late in the evening, compelling her employees to hang around with her even after work had ceased, pouring wine and talking nonstop, avoiding for as long as possible the return to her room at the Ritz and to the boredom and loneliness that awaited her there. She worked six days a week, and dreaded Sundays and holidays. As she told one confidant, “That word, ‘vacation,’ makes me sweat.”

In between the two world wars, Schiaparelli rose from obscurity to the top of the Paris fashion world, making dresses for Katharine Hepburn and Marlene Dietrich; collaborating with Salvador Dalí and Jean Cocteau; creating her own signature shade of pink, called Shocking—as well as her own signature perfume of the same name—and bringing dashes of surrealism to haute couture with hats in the form of lamb cutlets, pockets made to look like drawers, handbags shaped like balloons, and other playful unorthodoxies. Like so many self-made women, she was a workaholic. In his 1986 biography, Palmer White summarizes Schiaparelli’s daily routine:

Every morning Elsa rose at eight, no matter when she had gone to bed, sipped lemon-juice-and-water and a cup of tea for breakfast as she read the papers, handled private correspondence, made telephone calls and gave the menus of the day to the cook. Weather permitting, she often walked to work. “Always on time, five minutes early” was a motto with her. Punctual to the second everywhere in the world and livid if anyone else was one minute late, winter and summer she arrived at her office on the dot of ten. There she slipped a double-breasted white tailored cotton smock over her skirt and blouse or simple frock and outworked everyone until seven in the evening with power-house energy.

Although she spent long hours at the studio, Schiaparelli actually conceived her designs elsewhere. According to White, “Most of her designing Elsa did in her head, often while walking to work, alone in the countryside, driving or, later, riding in her chauffeur-driven Delage, lined in white pine and fitted with a bar. By nature a rebel who hated restrictions of any kind, she did not think well between walls.”

Elsa Schiaparelli, 1938

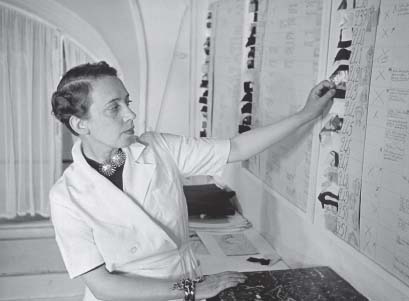

Graham established her own dance company in 1926 with a studio in New York’s Greenwich Village, then a hotbed of intellectual and artistic activity. But Graham was not particularly interested in what her neighbors were doing. “Most of my time was spent in the studio,” she wrote in her autobiography, Blood Memory.

Around this time, things in the Village were very intellectual. People would sit around and talk about things constantly. I never really went in for that. If you talk something out, you will never do it. You can spend every evening talking with your friends and colleagues about your dreams, but they will remain just that—dreams. They will never be made manifest—whether in a play, a piece of music, a poem, or a dance. Talk is a privilege and one must deny oneself that privilege.

Over her long and restlessly innovative career, Graham grew to be an expert in this kind of self-denial; dance was her life, and little else mattered, or was permitted to matter. Her longest-running personal relationships were with her music director and with the first male dancer in her company, to whom she was briefly married. After her divorce she considered adopting a child but decided against it. “I chose not to have children for the simple reason that I felt I could never give a child the caring upbringing which I had as a child,” she wrote. “I couldn’t control being a dancer. I knew I had to choose between a child and dance, and I chose dance.”

This is not to say she found the work enjoyable or easy. Dance was, she said, “permitting life to use you in a very intense way”—and the beginning of a new dance was “a time of great misery.” She came to her dances through long hours in the studio alone, testing her body, searching for physical movements that embodied emotions, especially those emotions that could not be expressed through language. She said, “Movement in modern dance is the product not of invention but of discovery—discovery of what the body will do.” But Graham also found inspiration outside the studio, in nature, in the people she met, and especially in the books she read. “I owe all that I am to the study of Nietzsche and Schopenhauer,” she once said. At night, she read voraciously, jotting down notes and copying passages that got her ideas flowing. Over time, the notes would begin to reveal a pattern, and Graham would next write out a scenario or script for her dance: “I would put a typewriter on a little table by my bed, bolster myself with pillows and write all night.”

Once Graham had a script, she would begin to work with a composer, gradually bringing together her scenario, the music, and the movements she had developed in the studio. When it came time to get her dancers involved, she allowed them to help her realize and refine her ideas—but, one member of her company recalled, “she was there every second of the time, shaping, molding, modeling.” When Graham ran into a “choreographic block,” she would stare out the window, thinking, while her dancers sat on the floor and waited. And when the work didn’t meet her high standards, she could become furious. “We used to watch her with alarm,” another of Graham’s dancers recalled. “She had her tantrums because she couldn’t draw out of herself all of the devils she kept inside her. When she couldn’t rid herself, cleanse herself, it was just frightful.” After “the purge,” however, would come a surge of “wonderful creativity.”

Graham continued to dance onstage until she was seventy-five, and was devastated when she finally had to retire. But she kept working as a choreographer up until a few weeks before her death at ninety-six. A dance critic who profiled Graham on the eve of her ninetieth birthday found her working as many as six hours a day, from 2:00 to 5:00 in the afternoon and again from 8:00 to 10:00 or 11:00 at night, with a break in between to rest and eat a light meal. Returning home at the end of the night, Graham dealt with paperwork and had a late supper of scrambled eggs, cottage cheese, peaches, and Sanka. Afterward she would watch old movies on television until 1:00 a.m., and then be up again at 6:30 in the morning (although she might go back to bed if she didn’t have any morning appointments). Even after a lifetime of dance, and the universal recognition of her genius, Graham was driven by chronic dissatisfaction. “Somewhere very long ago,” she wrote in Blood Memory, “I remember hearing that in El Greco’s studio, after he died, they found an empty canvas on which he had written only three words: ‘Nothing pleases me.’ This I can understand.”

Martha Graham in rehearsal, 1965

Bowen was an Anglo-Irish novelist and short-story writer whose books include The Death of the Heart, The Heat of the Day, and The House in Paris. In the late 1930s, the American poet May Sarton got to know Bowen in London, and observed how she divided her time between writing and entertaining. “I had never run a house, nor entertained, nor been responsible for ordering meals, and I had no idea what energy it all requires—the devouring machine that someone has to keep running smoothly,” Sarton wrote.

In Elizabeth’s life that machine had to be relegated to the periphery; central, of course, was her work. She worked extremely hard. No one saw her before one, and by then she had been at her desk for four hours. At one there was a break, lunch, and perhaps a short walk in Regent’s Park just outside her front door. After that break she went back to her study for two more hours. At four or half past tea was brought up to the drawing room and intimate friends often dropped in for a tête-a-tête.

When Alan [Cameron, her husband] came home at half past five, the tensions subsided and everything became cozy and relaxed. He embraced Elizabeth, asked at once where the devil the cat was—a large fluffy orange cat—and when he had found her, settled down for a cocktail and an exchange about “the day.” As in many successful marriages they played various games; Alan in his squeaky voice complained bitterly about some practical matter Elizabeth should have attended to, and she looked flustered, laughed, and pretended to be helpless. Alan’s tenderness for her took the form of teasing and she obviously enjoyed it. I never saw real strain or needling between them, never for a second.

Bowen and Cameron’s relationship has been described as “a sexless but contented union”; they were married for almost three decades, from 1923 until his death in 1952, but apparently the marriage was never consummated, and Bowen may have been a virgin until she started having extramarital affairs about ten years into the marriage. From then on, she had several affairs with men and women, including a thirty-year relationship with Charles Ritchie, a Canadian diplomat seven years her junior (who was also married for the latter twenty-five years of their affair). Despite the importance of these relationships to Bowen’s happiness, and to her fiction, she managed to keep them carefully compartmentalized: Apparently, Cameron never learned of her long-term relationship with Ritchie or any of her other lovers.

Bowen’s letters to Ritchie—and Ritchie’s diary entries during their affair—were published in 2008, and they provide valuable glimpses of Bowen’s creative process. “E was discussing her method of writing the other night,” Ritchie noted in March 1942.

She says that when she is writing a scene the first time, she always throws in all the descriptive words that come to her mind. . . . Like, as she said, someone doing clay-modelling who will smack on handfuls of clay before beginning to cut away and do the fine modelling. Then afterwards she cuts down and discards and whittles away. The neurotic part of writing, she says, is the temptation to stop for the exact words or the most deliberate analysis of a situation.

For her part, Bowen said that novel-writing was “agitating but makes me very absorbed, and in one kind of way happy.” Working on The Heat of the Day in 1946, she wrote, “I discard every page, rewrite it and throw discarded sheets of conversation about the floor. . . . From rubbing my forehead I have worn an enormous hole in it, which bleeds.”

“I have suffered two serious accidents in my life,” Kahlo once told a friend, “one in which a streetcar ran over me. . . . The other accident is Diego.” Kahlo married Diego Rivera in 1929 when she was twenty-two and the celebrated muralist was forty-two. She had started painting four years earlier, while convalescing from the gruesome streetcar accident that had fractured her spine and crushed her pelvis and one foot. (During her recovery, she taught herself to paint using a specially built easel that allowed her to work in bed.) Over the next several years, Kahlo followed Rivera to San Francisco, Detroit, and New York, where he had landed a series of prominent mural commissions; meanwhile, Kahlo continued to develop as a painter while yearning to return home. In 1934, Rivera reluctantly agreed and the married artists returned to Mexico City, where they had commissioned the architect Juan O’Gorman to build them a modernist house in the wealthy neighborhood of San Ángel. The dwelling was actually two houses, one for each artist, connected by a rooftop bridge and enclosed by a fence of tall cactuses. In her biography of Kahlo, Hayden Herrera summarizes the artists’ routine in San Ángel:

Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera at lunch, 1941

When all was well between Frida and Diego, the day usually began with a long, late breakfast in Frida’s house, during which they read the mail and sorted out their plans—who would need the chauffeur, which meals they would eat together, who was expected for lunch. After breakfast, Diego would go to his studio; occasionally he would disappear on sketching trips to the countryside, from which he would not return until late at night. . . .

Occasionally after breakfast, Frida would go upstairs to her studio, but she did not paint consistently, and weeks went by when she did not work at all. . . . More often, once the affairs of the household had been settled, the chauffeur would drive her into the center of Mexico City to spend the day with a friend.

One of Kahlo’s friends, the Swiss-born artist Lucienne Bloch, wrote in her diary that “Frieda [sic] has great difficulty doing things regularly. She wants schedules and to do things like in school. By the time she must get into action, something always happens and she feels her day broken up.” It didn’t help that Kahlo and Rivera’s relationship was never calm for long, with constant financial problems and numerous infidelities on both sides. Rivera’s conquests included Kahlo’s younger sister; Kahlo’s included Leon Trotsky, who was in exile from the Soviet Union. She made many of her most famous paintings in two periods of intense activity: in 1937–38, following her affair with Trotsky, and in 1939–40, during her temporary separation and divorce from Rivera. (They remarried after about a year, although Kahlo would never again live in the San Ángel residence, preferring to stay in La Casa Azul, her family home in the suburb of Coyoacán.)

In 1943, at Rivera’s suggestion, Kahlo began teaching at an experimental new painting and sculpture school where high school students from poor neighborhoods were given art supplies and free instruction. Kahlo enjoyed teaching, but inevitably it became yet another distraction from her own practice. In a 1944 letter, she described her routine as a teacher and artist:

I start at 8 A.M. and get off at 11 A.M. I spend half an hour covering the distance between the school and my house = 12 noon. I organize things as necessary to live more or less “decently,” so there’s food, clean towels, soap, a set-up table, etc., etc. = 2 P.M. How much work!! I proceed to eat, then to the ablutions of the hands and hinges (meaning teeth and mouth). I have my afternoon free to spend on the beautiful art of painting. I’m always painting pictures, since as soon as I’m done with one, I have to sell it so I have moola for all of the month’s expenses. (Each spouse pitches in for the maintenance of this mansion.) In the nocturnal evening, I get the hell out to some movie or damn play and I come back and sleep like a rock. (Sometimes the insomnia hits me and then I am fuc-bulous!!!)

Throughout the 1940s, Kahlo also had to contend with endless medical problems stemming from her streetcar accident; by the end of her life, she had endured more than thirty surgeries, and starting in 1940 she had to wear a series of steel-and-leather or plaster corsets to support her spine. As Kahlo’s health deteriorated, painting became more difficult; by the mid-1940s, she could neither sit nor stand for long periods of time. In 1950, the artist spent nine months in a Mexico City hospital, where she had a bone-graft surgery that became infected and required several follow-up surgeries. She made the best use of the time she could, once again employing the easel that allowed her to work lying on her back in bed. When the doctors permitted it, she would paint for up to four or five hours a day. “I never lost my spirit,” Kahlo said. “I always spent my time painting because they kept me going with Demerol, and this animated me and it made me feel happy. I painted my plaster corsets and paintings, I joked around, I wrote, they brought me movies. I passed [the year] in the hospital as if it was a fiesta. I cannot complain.”

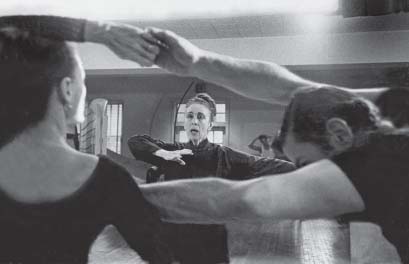

De Mille was born in New York City and grew up in Hollywood, the daughter of the screenwriter and director William C. de Mille and the niece of the legendary filmmaker Cecil B. DeMille (who altered his last name to look better on movie marquees). Told she was not pretty enough to be an actress, the young de Mille resolved to become a ballet dancer instead, returning to New York after college and touring the United States and Europe as a dancer while also beginning to work in choreography, which was where she made her real contribution to the field. Beginning with Rodeo, in 1942, de Mille pioneered a distinctly American style of dance that incorporated folk idioms into modern dance and classical ballet. In 1943, she choreographed Oklahoma!, the first in a string of hugely successful Broadway musicals; by the end of the 1940s, she was the best-known choreographer in the world.

To develop a new work of choreography, de Mille needed “a pot of tea, walking space, privacy and an idea,” she wrote in her 1951 memoir, Dance to the Piper. To begin, she would shut herself in a studio and listen to music—not from the musical or ballet in question (for musicals, the scores often wouldn’t be written yet) but music that inspired her, especially that of Bach, Mozart, and the Czech composer Bedřich Smetana, “or almost any folk music in interesting arrangements,” she wrote. Then the work began:

I start sitting with my feet up and drinking pots of strong tea, but as I am taken into the subject I begin to move and before I know it I am walking the length of the studio and acting full out the gestures and scenes. The key dramatic scenes come this way. I never forget a single nuance of them afterwards; I do usually forget dance sequences.

Agnes de Mille in rehearsal, 1964

The next step is to find the style of gesture. This is done standing and moving, again behind locked doors and again with a gramophone. Before I find how a character dances, I must know how he walks and stands. If I can discover the basic rhythms of his natural gesture, I will know how to expand them into dance movement.

It takes hours daily of blind instinctive moving and fumbling to find the revealing gesture, and the process goes on for weeks before I am ready to start composing. Nor can I think any of this out sitting down. My body does it for me. It happens. That is why the choreographic process is exhausting. It happens on one’s feet after hours of work, and the energy required is roughly the equivalent of writing a novel and winning a tennis match simultaneously. This is the kernel, the nucleus of the dance. All the design develops from this.

Once she had the kernel, de Mille sat down at her desk and worked out the pattern of the dances, and at this point she would listen to the score, if it existed. She made detailed diagrams and notes of her own invention, “intelligible only to me and only for about a week,” she wrote. Then she was ready to begin rehearsals, a process of several weeks. The biographer Carol Easton writes:

When a show was in rehearsal, Agnes saw little of her husband and even less of her child. She did not work at home—except in her head, before dawn. She had breakfast in a drugstore, away from the telephone and other interruptions, making notes while she ate. Mornings were for dance rehearsals, afternoons for the chorus. After that, to avoid interruption, she sometimes took a room at the Algonquin Hotel and worked there through dinner, returning to the theater to rehearse the actors until ten or eleven. When she got home, she made notes for the housekeeper about the next day before going to bed, usually with a headache.

After giving birth to her only child, a son, in 1946, de Mille hired a full-time housekeeper who handled almost all of the childcare duties, and she also hired the housekeeper’s husband, a chauffeur and general handyman. She could afford it: Following the success of Oklahoma!, de Mille’s annual earnings could top $100,000 in a good year, or more than a million dollars in today’s money. But her husband was never entirely comfortable with her success, and de Mille was aware that he had affairs on the side. She accepted this as something of an inevitability. When her friend the writer Rebecca West learned of her own husband’s infidelity, de Mille sent her a letter of empathy and support. “I have yet to meet the man who can accept with grace and comfort creativity in his wife,” she wrote. “Men can’t. They want to. But they feel dwarfed and obligated. . . . That’s how it is, darling. Gifted women pay. There are compensations.”

For de Mille, the compensations came in the rehearsal room. Which is not to say the work was easy; to the contrary, it proceeded with excruciating slowness—two hours of rehearsal might yield just five seconds of a final dance. De Mille was so protective of the work in progress that she sometimes stationed a guard at the door of the rehearsal room. Inside, she sat leaning forward in a chair, burning “with the concentration of an acetylene torch,” she said. Then she would spring to her feet to demonstrate a movement—only to stop abruptly and stand utterly still, in what one dancer called her “fish-out-of-water pose,” as she mentally processed the next part of the dance. De Mille was, she admitted, “apt to be short-tempered and jumpy at these times,” and her dancers learned to be patient—and to ply de Mille with cups of hot coffee, which she said comforted her. (By the end of a rehearsal, there would be a ring of empty cups surrounding her chair.) When she got stuck, “the tension could be painful,” one dancer recalled. “But when it was right,” said another, “she was triumphant! You felt like a real collaborator. The kick wasn’t just someone saying ‘Well done,’ but ‘YES, THAT’S IT!’ ”