Alcott wrote in fits of creative energy and obsession, skipping meals, sleeping little, and scribbling so furiously that she eventually had to train herself to write with her left hand to give her cramped right hand a break. “The fit was on strong and for a fortnight I hardly ate, slept, or stirred but wrote like a thinking machine in full operation,” she noted while working on her first novel, Moods. A more detailed account of Alcott’s writing binges can be found in her next and most famous novel, Little Women, in a passage about her heroine, Jo March, who has caught the writing bug at a young age, just as her creator had:

Every few weeks she would shut herself up in her room, put on her scribbling suit, and “fall into a vortex,” as she expressed it, writing away at her novel with all her heart and soul, for till that was finished she could find no peace. Her “scribbling suit” consisted of a black woolen pinafore on which she could wipe her pen at will, and a cap of the same material, adorned with a cheerful red bow, into which she bundled her hair when the decks were cleared for action. This cap was a beacon to the inquiring eyes of her family, who during these periods kept their distance, merely popping in their heads semi-occasionally to ask, with interest, “Does genius burn, Jo?” They did not always venture even to ask this question, but took an observation of the cap, and judged accordingly. If this expressive article of dress was drawn low upon the forehead, it was a sign that hard work was going on, in exciting moments it was pushed rakishly askew, and when despair seized the author it was plucked wholly off, and cast upon the floor. At such times the intruder silently withdrew, and not until the red bow was seen gaily erect upon the gifted brow, did anyone dare address Jo.

She did not think herself a genius by any means, but when the writing fit came on, she gave herself up to it with entire abandon, and led a blissful life, unconscious of want, care, or bad weather, while she sat safe and happy in an imaginary world, full of friends almost as real and dear to her as any in the flesh. Sleep forsook her eyes, meals stood untasted, day and night were all too short to enjoy the happiness which blessed her only at such times, and made these hours worth living, even if they bore no other fruit. The divine afflatus usually lasted a week or two, and then she emerged from her “vortex,” hungry, sleepy, cross, or despondent.

By all accounts, this was how Alcott herself worked—except that in place of a writing cap by which family members judged her availability for interruption, there was a “mood pillow” on the parlor sofa that served the same purpose. Alcott lived with (and financially supported) her parents for most of her adult life; during her writing fits, she generally holed up in her bedroom, working at the small half-moon desk that her father had built for her. But she was restless by nature and would sometimes move about the house as she daydreamed about her work. If she settled on the sofa, her parents or her sisters were occasionally tempted to interrupt her, but they knew from experience that breaking her concentration at a crucial moment would provoke the author’s extreme consternation. So Alcott turned a bolster pillow into a kind of “tollgate for conversation,” the biographer John Matteson has written. “If the pillow stood on its end, the family was free to disturb her,” Matteson explains. “If the pillow lay on its side, however, they should tread lightly and keep their interjections to themselves.”

An illustration from Louisa May Alcott’s Little Women, depicting Jo in her “scribbling suit”

Although Little Women contains the fullest description of Alcott’s writing vortex, the novel was actually composed without her usual creative mania. Alcott never felt inspired by the project and wrote it only to please her editor and her father, both of whom saw the lucrative potential of popular children’s books. This was in the late 1860s, when Alcott had just turned thirty-five, and by then she was already a seasoned writer of melodramatic short stories—“blood & thunder tale[s],” she called them, with titles like “The Maniac Bride” and “Pauline’s Passion and Punishment”—which she published under the pseudonym A. M. Barnard. She wrote the stories for money, often while working other jobs and attending to myriad domestic obligations, and she had long yearned to make the leap into more serious literature; Moods had been her bid for a complex, nuanced work for adult sensibilities. But as with most matters in her life, Alcott deferred to her father on the “girl’s book” he wanted her to write, and despite her lack of inspiration she worked fast, completing the novel’s 402 manuscript pages in just two and a half months. Brisk sales prompted her publisher to ask for a second volume, which Alcott wrote even more quickly, aiming for a chapter a day. She thought she could finish the book in a month, and nearly managed to do so. “I am so full of my work I can’t stop to eat or sleep, or for anything but a daily run,” she wrote.

When the second volume was published, Little Women quickly became a sensation, and from then on the “girl’s book” defined Alcott’s life. Although its success finally gave her the financial independence to write full-time, it also curtailed her ambitions. Her audience would forever want more of the same, and after so many years toiling in obscurity, Alcott could not resist satisfying the demand. “Though I do not enjoy writing ‘moral tales’ for the young,” she admitted in an 1878 letter, “I do it because it pays well.” Meanwhile, a host of chronic health conditions prevented Alcott from working with the same intensity as she once had; in a letter from 1887, she lamented that she could “write but two hours a day, doing about twenty pages, sometimes more”—an enormously productive day for most writers, but, for Alcott, a cause for concern and self-reproach.

“My daily life—I have no real life—this life is a dream, a dream of Duty,” Hall wrote in a 1934 letter. By then she was the author of several collections of poetry and seven novels, including, most famously, 1928’s The Well of Loneliness, a landmark of lesbian literature that was promptly banned as obscene in her native England. But she had not always felt duty-bound to writing. Born to wealthy but neglectful parents, Hall received a poor education and drifted throughout most of her adolescence and early adulthood, untethered to any vocation other than falling in and out of love with women whom she usually lost to marriage. That all changed with the first great love affair of her life, with the singer and composer Mabel “Ladye” Batten, who read voraciously, spoke several languages, and had no intention of sharing her life with an uneducated young dilettante. Determined to make herself worthy of Batten’s love, Hall began writing short stories, and Batten submitted some of them to a publisher. To Hall’s surprise, the publisher received them enthusiastically—but he insisted that Hall’s talents would be better served by a novel, and suggested that she begin work on one right away.

Hall demurred; she was not yet ready to embark on such a demanding project. But Batten’s death in 1916—before which Hall had begun an affair with Batten’s distant cousin, the sculptor Una Troubridge—injected a potent mixture of grief and guilt that stiffened her resolve. As Troubridge would later recall, Hall soon “launched upon an existence of regular and painstaking industry such as she had never before even dreamed of. The idle apprentice was metamorphosed by sorrow into someone who would work from morning to night and from night till morning, or travel half across England and back again to verify the most trifling detail.”

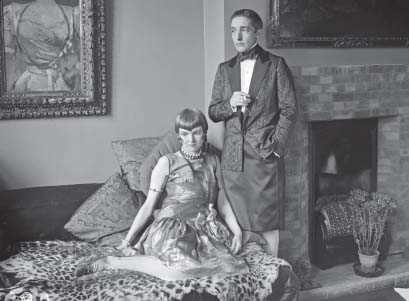

Radclyffe Hall (standing) with Una Troubridge, 1927

In this enterprise Hall was lucky to have found Troubridge, who became her lifelong lover and literary amanuensis—and who stoically endured Hall’s frequent struggles with “inspirational blackout,” and the black moods that accompanied them. Hall was never an effortless writer; she labored ferociously over her books, and her process was halting in the extreme. In a biography of Hall written after her death, Troubridge records her writing methods:

Whether she felt inspired or not, her method of work never varied. She never herself used a typewriter, in fact she never learned to type and the mere thought of dictating her inspiration to a typist filled her with horror. She always said that the written word was to her an essential preliminary and she wrote her work with pen or pencil, very illegibly, generally mis-spelt and often without punctuation. Sometimes she wrote in manuscript books but, especially in later years, often on loose sheets of sermon paper or indeed on paper of any kind, and to this day I will find scraps covered with sentences and sometimes discover “try outs” on a bit of blotting paper or an old cardboard box.

Hall chain-smoked as she worked, and she had a “neatness complex,” she wrote, whereby “anything in the nature of untidiness fidgets me to death.” Her writing wardrobe was unvarying. “I can never work in anything but old clothes, although these must always be very neat,” Hall told a reporter. “I usually work in an old tweed skirt and my velvet smoking jacket, a man’s smoking jacket by choice because of the loose and comfortable sleeves.”

After she completed a first draft, Hall would ask Troubridge to read it back to her, and as the reading progressed the author would dictate corrections, which Troubridge would mark on the pages and incorporate into the next reading. These readings had to be repeated many, many times until Hall was satisfied. “I have known a chapter worked on for weeks on end,” Troubridge recalled. “I have often read one aloud a score of times.” And if her reading evinced even a hint of flatness or boredom, Hall would seize on this as evidence of the writing’s deficiency, and sometimes snatch the pages from Troubridge’s hands and throw them into the fire. When, on the other hand, Hall was finally satisfied with the reading-aloud stage, she would next dictate the corrected draft to a typist, and then the process would begin all over again. In this manner, draft by painstaking draft, Hall would creep toward a final version, relying on Troubridge’s endless readings aloud as her essential quality check.

As she got older, Hall only worked harder. In her later years, she gravitated increasingly toward writing first drafts at night, as a result of which, Troubridge recalls, “she never really got enough sleep. Not only had she always suffered from insomnia but after a night of intensive work—a stretch of perhaps sixteen hours on end during which she had reluctantly swallowed such food as I gave her, without leaving her desk—even when she finally almost fell into bed, within a couple of hours she would be wide awake, asking for her breakfast or going over her work.” Once she developed her fanaticism for writing, Hall didn’t know any other way to be. In a 1934 letter, she said, “I literally wear myself out over a book, too much I suppose, but there it is.”

The Irish-born, French-based architect and furniture designer helped revolutionize the look of modern homes but was proudly incompetent at running her own. “Oh, how I abominate housework,” she once said—and she avoided this and other domestic obligations by employing a faithful housekeeper, Louise Dany, who attended to her needs from 1927 until Gray’s death almost fifty years later. Gray also insisted on being driven everywhere. (In the 1910s, her favored chauffeur was the singer Marisa Damia, whose pet panther would join them on joyrides around Paris.) “Artists ought not to drive at all,” she wrote in a letter to her niece. “First of all, they are too precious, secondly, driving prevents their thoughts wandering where they should, thirdly, it puts constant tension on their eyes.” And Gray needed to preserve her eyesight for her work, which was really the only thing in her life that she cared about. As she wrote in her nineties, “Only work of some sort can help to give meaning to life even if it is really quite useless.”

Duncan essentially invented modern dance and became an international star as a result, but her artistic triumph never made her wealthy; for most of her career she worried about how to pay her expenses, many times rehearsing in a freezing studio because she couldn’t afford to heat it. (The problem may have been less about making money than holding on to it: According to the journalist Janet Flanner, Duncan “once gave a house party that started in Paris, gathered force in Venice and culminated weeks later on a houseboat on the Nile.”) During one of her European tours, Duncan started joking with her sister that the solution, clearly, was to find a millionaire. Then, the morning after a performance in Paris, one appeared—Paris Singer, heir to the Singer sewing machine company fortune, a six-foot-three, blond, bearded arts patron who had fallen for Duncan and come to sweep her off her feet. Duncan was willing enough—but Singer soon proposed marriage, an institution she abhorred. Singer wanted the great dancer to live with him in London and on his estate in the English countryside. Duncan, accustomed to touring relentlessly before adoring crowds, wasn’t sure she could tolerate such a settled life. What would she do with herself? Try it for three months, Singer proposed. “So that summer we went to Devonshire,” Duncan wrote in her autobiography,

Isadora Duncan at the Acropolis of Athens, circa 1910s or 1920s

where he had a wonderful château which he had built after Versailles and the Petit Trianon, with many bedrooms and bathrooms, and suites, all to be at my disposition, with fourteen automobiles in the garage and a yacht in the harbor. But I had not reckoned on the rain. In an English summer it rains all day long. The English people do not seem to mind at all. They rise and have an early breakfast of eggs and bacon, and ham and kidneys and porridge. Then they don mackintoshes and go forth into the humid country till lunch, when they eat many courses, ending with Devonshire cream.

From lunch to five o’clock they are supposed to be busy with their correspondence, though I believe they really go to sleep. At five they descend to their tea, consisting of many kinds of cakes and bread and butter and tea and jam. After that they make a pretence of playing bridge, until it is time to proceed to the really important business of the day—dressing for dinner, at which they appear in full evening dress, the ladies very décolleté and the gentlemen in starched shirts, to demolish a twenty-course dinner. When this is over they engage in some light political conversation, or touch upon philosophy until the time comes to retire.

You can imagine whether this life pleased me or not. In the course of a couple of weeks I was positively desperate.

Duncan did not agree to marry Singer, or to ever again follow such a regimented lifestyle. She preferred to spend “long days and nights in the studio seeking that dance which might be the divine expression of the human spirit through the medium of the body’s movement.” Although, even for Duncan, not every day could be a joyous communion with art; sometimes she looked back on her life and was “filled only with a great disgust and a feeling of utter emptiness.” But Duncan believed that this, too, was a part of the artist’s life. “I have met many great artists and intelligent and so-called successful people in my life, but never one who could be called a happy being, although some have made a very good bluff at it,” she wrote. “Behind the mask, with any clairvoyance, one can divine the same uneasiness and suffering.”

The French novelist began writing at the behest of her first husband, Henry Gauthier-Villars, a popular writer (and notorious libertine) who published under the nom de plume Willy. Suspecting that Colette’s coming-of-age experiences would make compelling fiction, he urged her to write them down—and play up the more salacious bits—and then published the resulting novel, Claudine à l’école, under his own name. The book was a commercial and critical success, and Willy demanded more; according to Colette, he would lock her in her writing room and wouldn’t allow her to emerge until she had completed her daily quota of pages. “A prison is indeed one of the best workshops,” Colette wrote many years later. “I know what I am talking about: a real prison, the sound of the key turning in the lock, and four hours’ claustration before I was free again.”

Colette at work, circa 1950

Colette eventually divorced Willy and began publishing under her own name, drawing on her numerous affairs with men and women for novels well stocked with sensual adventures; by the end of her life, she had written more than fifty books and had become a national institution in France, beloved especially for her novels Chéri and Gigi. Colette never enjoyed writing, but thanks to Willy’s early “training,” she forced herself to do it nearly every day. Her stepson Bernard—with whom Colette had a five-year affair, beginning when he was sixteen and she was forty-seven—had “the opportunity to watch her work early in the morning,” he later recalled. “Wrapped up in a blanket, she attacked the blue pages she always wrote on. It was a great lesson for me, for she would fill four or five pages easily, then throw away the fifth, and so on in this manner until she was tired.”

Colette didn’t always write first thing. According to her third husband, “She was wise enough never to write in the morning, but to go out for a walk with her dog, whatever the weather. . . . She never worked in the evening except when pressed by circumstance.” Rather, he said, it was “chiefly between three and six in the afternoon” that she composed her day’s work. As she grew older and began suffering from arthritis, Colette preferred to write on the sofa, stretched out on her “raft” with a blue-shaded lamp (blue was her favorite color) hovering above her lap table. Writing for her meant, she wrote, “idle hours curled up in the hollow of the divan, and then the orgy of inspiration from which one emerges stupefied and aching all over, but already recompensed and laden with treasures that one unloads slowly on to the virgin page in the little round pool of light under the lamp.” Once inspiration struck, she wrote fast, furiously filling page after page—although, the next day, she didn’t necessarily approve of what she had written. “To write is to pour one’s innermost self passionately upon the tempting paper,” she wrote, “at such frantic speed that sometimes one’s hand struggles and rebels, overdriven by the impatient god who guides it—and to find, next day, in place of the golden bough that bloomed miraculously in that dazzling hour, a withered bramble and a stunted flower.”

Fontanne and her husband, Alfred Lunt, created probably the greatest husband-and-wife acting team in theatrical history, working together in more than two dozen productions from 1923 to 1960. Their success was the result of mutual perfectionism and constant, almost obsessive rehearsal. “Miss Fontanne and I rehearse all the time,” Lunt once said. “Even after we leave the theater, we rehearse. We sleep in the same bed. We have a script on our hands when we go to bed. You can’t come and tell us to stop rehearsing after eight hours.”

In his biography The Fabulous Lunts, Jared Brown describes the couple’s rehearsal process inside their apartment on Manhattan’s East 36th Street:

They worked out a meticulous routine for their sessions at home. Memorization of lines came first. Since the apartment had three stories, with the dining room on the ground floor, the bedrooms on the second and a studio-living room on the third, Fontanne would take the top floor and Lunt the lowest. Each would thus be able to shout out the lines of the play without disturbing the other. . . . After both felt reasonably secure in their lines, they worked in the same room, sitting facing one another on two plain wooden chairs. With legs interlocked and eyes focused squarely on each other, they began to exchange dialogue. If one of them faltered or gave the wrong line, the other clapped his knees together and the scene began again. After several such sessions, their knees may have been bruised but they were letter-perfect in their lines.

Alfred Lunt and Lynn Fontanne, with a script, 1931

Once the memorization was complete, rehearsals began, with Fontanne and Lunt playing each scene over and over again, each time modifying their characters’ attitude and intentions. After multiple run-throughs, they would come to an agreement about which version had been most successful, and then they would begin yet another round of rehearsals, now stopping mid-scene as needed to discuss the finer points of each other’s performance, making small modifications to gestures, looks, points of emphasis, relentlessly polishing every detail. Only after this extensive “homework” would the Lunts be ready to rehearse with the other actors in a production—and even then, they continued to rehearse by themselves at home afterward. “Over a period of weeks, each scene was repeated, with modifications, hundreds of times,” Brown writes. And these were not gentle, supportive sessions—the Lunts were hard on each other. Indeed, Fontanne thought that this was probably the secret to their success. “I think that we are terrifically critical of each other,” she once said. “And we’ve learned, the both of us, to take it.”

“When I am working on a book I work all the time,” the American poet told a reporter in 1931. “I always have notebook and pencil on the table at my bedside. I may wake up in the middle of the night with something I want to put down. Sometimes I sit up and write in bed furiously until dawn. And I think of my work all the time even when I am in the garden or talking to people. That is why I get so tired. When I finished [the poetry collection] ‘Fatal Interview’ I was exhausted. I was never away from the sonnets in my mind. Night and day I concentrated on them for the last year and a half.”

Edna St. Vincent Millay at Steepletop, circa 1930s

By this time Millay had been living for several years at Steepletop, the abandoned berry farm that she and her husband purchased in 1925 and transformed into an elegant country estate with extensive gardens; an outdoor bar; a tennis court; a spring-fed pool, where guests were invited to swim in the nude; and a secluded writing hut for Millay (although she often wrote in the main house, lying in bed). Millay’s husband, a Dutch coffee importer named Eugen Boissevain, had given up his business to run Steepletop, which proved a near-perfect arrangement for the poet. When a visiting reporter asked Millay how she managed such a large and complicated household, Millay explained that she had nothing to do with it:

Eugen does all that kind of thing. He engages the servants. He shows them around. He tells them everything. I don’t interfere with his ordering of the house. If there is anything I don’t like, I tell him. I have no time for it. I don’t want to know what I’m going to eat. I want to go into my dining room as if it were a restaurant, and say, “What a charming dinner!”

It’s this concern with my household that protects me from the things that eat up a woman’s time and interest. Eugen and I live like two bachelors. He, being the one who can throw household things off more easily than I, shoulders that end of our existence, and I have my work to do, which is the writing of poetry.

Ignoring the household did not exactly come naturally to Millay. “I care an awful lot that things be done right,” she said. “Yet I don’t let my concern break in and ruin my concentration and my temper.” She considered writing poetry an extremely delicate process and took pains not to let everyday worries disrupt it. “When you write a poem something begins to be a part of your thought and your life,” she said, “and you become more and more conscious of it. It forms as if conjured out of steam.” Once she had completed a first draft, she would work it over and over, often setting a poem aside for months or even as long as two years. “I put it away until it is cold,” she said, “and I get a critic’s point of view toward it as if it weren’t mine at all, and only when it has satisfied my most searching analysis do I let it out.”

All of this required tremendous energy, and while it appeared to guests that Millay and her husband were living a life of ease in the country, Millay was in fact pushing herself to the brink of collapse. “I can spade a garden and not get tired,” Millay said, “but the nervous intensity attendant on writing poetry, on creative writing, exhausts me, and I suffer constantly from a headache. It never leaves me while I am working, and for that there is no cure save not to work. Doctors advise me to go away for a rest cure, but who wants to lie stretched on one’s back idle for months at a time?”

“I have three phobias which, could I mute them, would make my life as slick as a sonnet, but as dull as ditch water: I hate to go to bed, I hate to get up, and I hate to be alone,” Bankhead wrote in her 1952 autobiography. The first two phobias can be attributed, in part, to the Alabama-born actress’s chronic insomnia; the last seemed to be congenital, and may have been tied up with her love of—even addiction to—conversation, although conversation for Bankhead was invariably a one-sided affair. Her preferred mode of being was monologue, to be carrying on an endlessly digressive mix of anecdotes, witticisms, and unintentional one-liners (e.g., “We’re reminiscing about the future”; “I’ve had six juleps and I’m not even sober”). A friend of Bankhead’s once measured her rate of words per minute, and estimated her daily output at just under seventy thousand (almost the length of this book). Another famously reported, “I’ve just spent an hour talking to Tallulah for a few minutes.”

Bankhead claimed that she called everyone “dahling” because she could never remember names—just as she could never remember directions, addresses, or telephone numbers. But she had no trouble memorizing her lines during her five-decade theatrical career; indeed, onstage she was able to press her outsize personality into the service of flamboyant and fierce performances that made her one of her century’s greatest leading ladies. Bankhead, however, dismissed acting as “sheer drudgery” and claimed it barely even qualified as a creative profession:

The author writes a play, then is through with it, aside from collecting royalties. Four weeks of rehearsing and the director’s work is done. Theirs are creative jobs. But how would the author feel if he had to write the same play over each night for a year? Or the director restage it before each performance? They’d be as balmy as Nijinsky in a week. Even the ushers traffic with different people every night. But the actress? She’s a caged parrot.

Bankhead also loathed the strict timetable of the theater, the necessity to appear nightly from 8:30 to 11:00 p.m., without any room for error or improvisation. “Above the members of any other profession actors are slaves to the clock,” she wrote. Not that she was ever tardy—another of Bankhead’s phobias was being late to an appointment, and she generally arrived everywhere at least thirty minutes early. Before opening nights, she was struck with “pre-show terror,” a rare lapse in her otherwise indefatigable persona. And although Bankhead disapproved of superstitions, she admitted to indulging in them on these occasions. “Ever since The Squab Farm [her first production] a framed picture of my mother had graced my dressing-room table on opening nights,” Bankhead wrote. “Unfailingly I would drop on my knees just before curtain rise and pray: ‘Dear God, don’t let me make a fool of myself.’ Then I would open a split of champagne and my maid and I would drink to our good fortune.”

Nilsson was one of the great opera singers of her era, renowned for her rich, powerful soprano voice and her definitive interpretations of the operas of Strauss and, in particular, Wagner. She grew up a farmer’s daughter in southern Sweden, where she was encouraged to sing by a local choirmaster; after studying at Stockholm’s Royal Academy of Music, Nilsson gradually built an international reputation and, from the late 1950s until her retirement in 1984, was constantly in demand. Asked how she maintained her instrument over such a long career, Nilsson demurred. “I do nothing special,” she said. “I don’t smoke. I drink a little wine and beer. I was born with the right set of parents.” On another occasion, she was asked the secret to her success as Wagner’s Isolde. “Comfortable shoes,” she said.

The real secret to her success was discipline, which Nilsson said was particularly important for a singer. “A writer or painter can work when they feel the inspiration,” she said. Singers aren’t so lucky:

A singer can awaken in the morning with a headache and feel very bad, and you’ll be nervous and everything is against you, but you have to regain the strength for the performance that night. It’s a very tough feeling. The more responsibility you feel, the more nervous and impossible you get. At times like that, you go very early to the theater and try little by little to get in shape. And most of the time those troubles are forgotten when you are onstage, and that’s wonderful. I guess it’s like giving birth to a child—when the child is there in your arms, it’s wonderful and you forget the pain of before.

For many years Nilsson performed almost continually, traveling from one opera house to another, living in hotels for months on end. She didn’t take vacations of any length, saying, “If you rest too long, it is harder to bring the voice back into shape.” And although she and her husband, a Swedish businessman, maintained apartments in Stockholm and Paris, she did not consider either of them—or any place—her home. “I cannot be an artist and have a home,” she once said. “You have to say ‘No, thank you’ to either one. I say ‘No, thank you’ to a home. I love my profession so much, and my husband is so understanding.”

Despite her renown, Nilsson never relished the role of the diva off-stage. “I don’t like that expression ‘prima donna,’” she said. “I feel more like a working soprano.” Her performance rituals were simple: Before going onstage, she performed a rapid series of vocal warm-ups that lasted three to four minutes and, according to eavesdroppers, sounded “perfectly awful.” During intermission, she sucked on an orange; after a performance, she had an attendant bring her a glass of beer, a jigger of aquavit, and a Swedish herring from the personal supply she carried with her wherever she went.

In March 1951, Hurston wrote a letter to her literary agent thanking her for a $100 check and sharing some news about the novel she had recently started writing. “I have caught fire on the novel, and I am back at work on it already,” Hurston wrote.

Zora Neale Hurston, 1938

I do not know whether you ever went down to the Matanza river in your pig-tail days to fish and caught a toad fish. You know if they are swallowed by a big fish, they will eat their way out through the walls of its stomach. That is like the call to write. You must do it irregardless, or it will eat its way out of you anyhow.

It’s a pretty good metaphor for how Hurston worked. She never followed a writing routine or plan, and she went through “terrible periods” when she couldn’t write at all. “Every now and then I get a sort of phobia for paper and all its works,” she wrote in a 1938 letter. “I cannot bring myself to touch it. I cannot write, read, or do anything at all for a period. . . . Just something grabs hold of me and holds me mute, miserable and helpless until it lets me go. I feel as if I have been marooned on a planet by myself. But I find that it is the prelude to creative effort.”

Once she was seized by a creative idea, everything changed. Hurston wrote her most famous novel, Their Eyes Were Watching God, in the fall of 1936, while on a Guggenheim Fellowship researching voodoo culture in Haiti. In the previous months she had been in Jamaica living with and studying the Maroons, descendants of escaped slaves, and the immersion in Jamaican and Haitian culture helped Hurston see her own country’s race, class, and gender issues in a new light. Once she began Their Eyes Were Watching God, she worked with amazing speed. “It was dammed up in me, and I wrote it under internal pressure in seven weeks,” Hurston wrote in her autobiography. “I wish that I could write it again.”

Bourke-White was a pioneering photojournalist with a career of firsts: She was the first Western photographer allowed to enter the Soviet Union, the United States’ first female war correspondent, and the first female staff photographer at Life magazine, where she was known by her colleagues as “Maggie the Indestructible” for her daring forays into sites of global conflict, from which she inevitably emerged unscathed and undaunted. Due to the nature of her work, Bourke-White could never really follow a fixed schedule as a photographer, instead adapting as needed to the assignment on hand. But she was also a gifted writer—publishing several books on her work and a lively autobiography, Portrait of Myself—and here she did follow extremely regular habits. Indeed, photography and writing proved an ideal pairing for Bourke-White: “I wanted to have a rhythm in my life: the high adventure—with all the excitement, the difficulties, the pressures—balanced with a period of tranquility in which to absorb what I had seen and felt,” she wrote. And her house in Darien, Connecticut, “isolated by surrounding woods,” proved the perfect setting for these periods of tranquility. “I am a morning writer,” Bourke-White noted in Portrait of Myself.

The world is all fresh and new then, and made for the imagination. I keep an odd schedule that would be possible only for someone with no family demands—to bed at eight, up at four. I love to write out of doors and sleep out of doors, too. In a strange way, if I sleep under open sky, it becomes part of the writing experience, part of my insulation from the world.

For outdoor writing and sleeping, Bourke-White employed “a piece of garden furniture on wheels, with a little fringed half-canopy on top,” she wrote. “It was wide and luxurious, and when it was made up with light quilts and a candle on each side, and reflected in the swimming pool, it was a child’s dream of a bed made for a princess.” Each night she would roll it to a different spot on her property and fall asleep as the sun set and the fireflies emerged. Just before daylight she would wake and begin writing, “and by the time the sun rose, I was sealed in my own planet and safe from the distractions of the day.”

This last point was crucial: Bourke-White required long periods of solitude to write, with as few interruptions as possible. She was aware that this could be difficult for outsiders to accept. “I’m afraid my closely guarded solitude causes some hurt feelings now and then,” she wrote. “But how to explain, without wounding someone, that you want to be wholly in the world you are writing about, that it would take two days to get the visitor’s voice out of the house so that you could listen to your own characters again?” In fact, friends and colleagues were sometimes put out by Bourke-White’s relentless focus on her work. “The very first time I met her I asked her if she would have lunch with me,” the Life photographer Nina Leen once recalled. “She told me she was writing a book and there was no hope of a lunch for several years.”