Marie Bashkirtseff, circa 1876

Bashkirtseff was a Russian-born painter and sculptor who kept a diary from age thirteen until shortly before her death of tuberculosis at twenty-five. During that time she studied painting in Paris (at a private academy; the famous École des Beaux-Arts did not admit women until 1897) and began to establish herself as a gifted young artist. “I hate moderation in anything,” she wrote in 1876, the year she began to study art seriously. “I want either a life of continual excitement or one of absolute repose.” In fact, she chose continual work, for years following more or less the same schedule: up at 6:00 a.m., drawing or painting from 8:00 to noon and from 1:00 to 5:00, with an hour-long meal break in between. Then she bathed and changed clothes, had dinner, read until 11:00 p.m., and went to bed. (Sometimes she would draw by lamplight in the early evening before dinner, extending her workday by an hour or so.) Occasionally, she grew fatigued of the relentless schedule, but, as she wrote in 1880, “when I spend the day without working I suffer the most frightful remorse.” Learning that she had tuberculosis and would likely die young only increased Bashkirtseff’s determination. “Everything seems petty and uninteresting, everything except my work,” she wrote in May 1883. “Life, taken thus, may be beautiful.”

“One must, in one’s life, make a choice between boredom and suffering,” Madame de Staël wrote to a friend in the summer of 1800. In her own life, Staël proudly chose suffering. The Swiss-French woman of letters was born into enormous wealth and status—her father was Louis XVI’s minister of finance, her mother a central figure in the salons of Paris—but her outspoken opposition to Napoleon in the 1790s forced her into exile, much of it spent at her family residence in Coppet, Switzerland, which became an important meeting place and laboratory of ideas for many of Western Europe’s leading intellectuals. There Staël also wrote numerous political and literary essays, although her productivity was not always apparent to her guests. “Madame de Staël worked a great deal, but only when she had nothing better to do; the most trifling social amusement always had priority,” one visitor noted. That’s not quite true. In his biography of Staël, J. Christopher Herold provides a more nuanced portrait of her lifestyle in Coppet:

Breakfast was between ten and eleven. Then the guests were left to their own devices, while Germaine devoted herself to her business correspondence, her accounts, the administration of her estate, and, if there was time, to reading and writing. To her guests it seemed that she was doing nothing, for she was able to busy herself with several matters at a time, and interruptions, which were continuous, did not set her back. She took notes while riding in her carriage, kept up running conversations while dictating letters, and worked at her books no matter where she happened to be or what was going on. Even to those closest to her it was a mystery how she could write so much when there seemed to be no time for writing. The secret was not in any special organization of time; rather, it was in absolute lack of organization. Most men expend the larger part of their time on trying to concentrate and on resting from the effort; between preparation and relaxation there is hardly time left for action. Madame de Staël, always concentrated, never at rest, was endowed with a brain that could, in an instant, adjust itself to whatever demanded her attention.

Because breakfast at Coppet was between 10:00 and 11:00 a.m., lunch wasn’t served until about 5:00 p.m., and dinner not until 11:00 p.m. In between lunch and dinner, there was an evening walk or drive, or a gathering for music, conversation, and games. After dinner, conversation continued until the early morning, at least for Staël and her inner circle. Staël slept only a few hours a night—and then only thanks to a dose of opium—and she expected a similar level of stamina in her intimates. “Like all insomniacs,” Herold writes, “she resented fatigue in others as a manifestation of disaffection.” Staël’s longtime lover, the politician and author Benjamin Constant, said that he had never known anyone “more continuously exacting without realizing it.” He wrote, “Everybody’s entire existence, every hour, every minute, for years on end, must be at her disposition, or else there is an explosion like all thunderstorms and earthquakes put together.”

Madame du Deffand was an intimate friend and correspondent of Voltaire, Montesquieu, and Horace Walpole, and the hostess of a Parisian salon that stood at the center of the city’s intellectual life for forty years. In his book Written Lives, Javier Marías summarizes Deffand’s daily routine:

Her life followed a slightly disorderly timetable: she would get up at about five o’clock in the afternoon and, at six, receive her supper guests, of whom there might be six or seven or even twenty or thirty depending on the day; supper and talk went on until two in the morning, but since she could not bear to go to bed, she was quite capable of staying up until seven playing at dice with [the British politician] Charles Fox, even though she did not enjoy the game and was, at the time, seventy-three years of age. If no one else could keep her company, she would wake the coachman and have him take her for a ride along the empty boulevards. Her aversion to going to bed was due in large part to the terrible insomnia from which she had always suffered: sometimes, she would await the early morning arrival of someone who could read to her, and then, after listening to a few passages from a book, she could at last fall asleep.

The central event of Deffand’s day was supper—“one of man’s four aims,” she wrote; “I have forgotten what the other three are”—and she continued hosting her evening supper parties right up until her death at age eighty-three. “Exert all your talents,” she often told her cook, “as I more than ever require the aid of society to beguile the time.” As Marías noted, she was especially loath to be left alone at night. After her visitors finally went home and her servants retired, Deffand wrote, “I am left to myself, and I cannot be in worse hands.”

“If you have any young friends who aspire to become writers, the second greatest favor you can do them is to present them with copies of The Elements of Style,” Parker once said. “The first greatest, of course, is to shoot them now, while they’re happy.” Parker was only half-joking, or maybe not even half. Despite becoming a much-sought-after writer, with high-profile, well-paying gigs at Vanity Fair and The New Yorker, Parker loathed the writing process and barely managed to get her articles in on time. She never followed any particular writing routine, although when she was a reviewer for The New Yorker there was a kind of weekly routine, a push-and-pull act between the reluctant author and her editor, which Marion Meade describes in her biography of Parker:

A 1945 telegram from Dorothy Parker to her editor

Almost from the outset, she set a precedent of being late with her copy, which was due at The New Yorker on Fridays. On Sunday mornings, someone from the magazine would telephone. Dorothy, reassuring, said that the column was finished except for the last paragraph and promised to have it for them within the hour. Throughout the day, the same routine would be repeated several times. Occasionally, she would claim she had just ripped up the column because it was awful. At that point, she would start writing.

She did this with all her editors. An editor at The Saturday Evening Post remembered the process this way: “You sit around and wait for her to finish what she has begun. That is, if she has begun. The probability is that she hasn’t begun.” An editor at Esquire confirmed that Parker “had a miserable time writing,” and compared the process of extracting copy to a difficult childbirth, with the editor as obstetrician—the operation was, he said, a “high-forceps delivery.” Parker hated it as much as her editors did, but she couldn’t change. She was once asked by an interviewer what she did for fun. “Everything that isn’t writing is fun,” she replied.

“I know of no professional writer who doesn’t get to work every day as does a stenographer or a bus driver or a President of the United States,” Ferber wrote in her 1963 autobiography, A Kind of Magic. “The difference is that the writer is accountable to no one but himself, which makes for a tough taskmaster; and the writer works as a rule seven days a week instead of the usual worker’s five.”

From the age of twenty-one until the end of her life, Ferber sat down at the typewriter every morning at 9:00 a.m. and aimed for one thousand words a day. Although she didn’t always meet this mark, she often did, producing twelve novels, twelve short-story collections, nine plays, and two autobiographies in her fifty-year career. (In 1921, she won the Pulitzer Prize for her novel So Big, although she is probably better known for her novels Show Boat, Cimarron, and Giant.) The author’s writing surroundings were unimportant; over the years, Ferber said, she had trained herself to work in virtually any conditions: “I have written in bathrooms and aboard ships; on jet planes and in woodsheds; on trains between New York and San Francisco or Paris to Madrid; in bed at home or propped up on a hospital contraption; in hotels; cellars, motels, automobiles; well or ill, happy or despairing.”

There was one exception to this rule. When Ferber built her dream house in Connecticut, she had the opportunity to create her ideal workroom, a second-floor study with “caramel carpet, soft green walls, fireplace, bookshelves, armchair, desk-chair, desk, typewriter”—and three windows, facing east, west, and south, with expansive views of her thirty-five-acre estate. Soon, however, she dragged her desk away from the windows to face the room’s one blank wall. She immediately felt better. “A room with a View,” she declared, “is not a room in which a working writer can write.”

Mitchell began writing Gone with the Wind, her first novel, around 1928 and finally handed it over to a visiting editor in the fall of 1935. Though she had been a successful journalist before turning to fiction, Mitchell found novel-writing exceptionally difficult. “I do not write with ease, nor am I ever pleased with anything I write,” she said in a letter, and she told an interviewer, “Writing is a hard job for me. Night after night I have labored and labored and have wound up with no more than two pages. After reading those efforts on the morning after, I have whittled and whittled until I had no more than six lines salvaged. Then I had to start all over again.” She estimated that, with a few exceptions, each chapter of Gone with the Wind was rewritten “at least twenty times.”

Mitchell wrote in the living room, wearing a green eye-shade and men’s pants to simulate the newsroom conditions that had proved congenial in her earlier career. As she wrote, she felt the presence of “something strange, something headlong and desperate,” she said. She didn’t write every day, or on any kind of strict timetable; indeed, she frequently took weeks and months away from the book, often because of various accidents and ailments (some of which were certainly more mental than physical in nature—Mitchell was a dedicated hypochondriac). When she was working, Mitchell was obsessive about her privacy. “I not only did not ask anyone to assist me but I fought violently against letting even close friends read as much as a line,” she said in 1936. Many of her friends didn’t even learn of Gone with the Wind’s existence until it was nearly done, and they knew nothing about the plot until it was published. Once, when a friend showed up unannounced, surprising Mitchell at her typewriter, the author leapt from her seat and threw a bath towel over the table.

Even after the tremendous success of Gone with the Wind—which sold millions of copies, was made into a classic movie, and won the Pulitzer Prize in 1937—Mitchell was never tempted to write another book. “I wouldn’t go through this again for anything,” she said.

Anderson was an American contralto who, in 1955, became the first black soloist to appear at the Metropolitan Opera, in New York. The conductor Arturo Toscanini said she had “a voice such as one hears once in a hundred years.” In her autobiography, Anderson wrote about her method of learning a new song, a more complex and delicate process than audiences might imagine. “I like to hear the melody first, to get something from the music before I have begun serious work on the words,” she wrote.

Then I read the [words] apart from the music; I want to know what it is about. I want to know something about the way in which the song was written. I try to saturate myself in everything that relates to it. When I put words and music together I try to reach deeply into the mood. If I concentrate, and if there is nothing in the song to create unexpected difficulties, the task is not hard.

It is not always easy, however, to concentrate; your mind has to be free of distractions. Household and family obligations have their rights, and do occupy my thoughts a great deal, and other calls on my time may intrude. No matter how study has gone during the day, I take the songs to bed with me. Just before one is ready to sleep there comes the time of complete relaxation, and one lives the mood of the music. Suddenly one is wide awake, completely lost in the spirit of the song, and in a few hours, while all is still around one, a great deal is accomplished.

“Music is an elusive thing,” Anderson continued. Some weeks she worked on a song every day without making any progress. “Then,” she wrote, “suddenly there is a flash of understanding. What has appeared useless labor for days becomes fruitful at an unpredictable moment.”

Marian Anderson performing at the Lincoln Memorial, Washington, D.C., 1939

When she was nine years old, Price was taken by her mother to Jackson, Mississippi, to hear Marian Anderson sing. From the moment Anderson opened her mouth Price knew exactly what she wanted to do with her life, and against long odds she achieved her dream, rising from the segregated South to the Juilliard School of Music in New York City and, eventually, the Metropolitan Opera, becoming one of the Met’s leading sopranos in the 1960s. According to the biographer Hugh Lee Lyon, Price’s performance days followed an invariable routine: “On the day of a performance she gets up late and has a brunch consisting of a big glass of orange juice, two boiled eggs and café au lait,” Lyon writes. “At five o’clock, she usually has a steak, baked potato, salad and coffee. Then Lulu Schumaker [her live-in housekeeper] prepares her a vacuum of hot broth to take with her to the opera house. She sips some of the broth between some of the scenes.” More important than Price’s daily routine, however, was her performance schedule, which needed to incorporate plenty of time off between dates. If at all possible, Price would not agree to more than two performances every eight to ten days. “Opera is a very tricky thing,” she once explained. “It demands a lot. You need a day before a performance to prepare; the day of the performance to crack up, if you have to; and the day after to recuperate. How can you sing on either of those days? You blow your brains out and are exhausted which, believe me, I’ll never do again. I much prefer to sing on my interest than my capital.”

Leontyne Price in rehearsal, 1962

Lawrence was an English actress best known for her performances in Noël Coward’s comedies and musicals—including 1930’s Private Lives, which he wrote with her in mind—and also noted for her vivaciousness onstage and in person. (When a fan once asked Lawrence’s doctor what vitamins she took to be so energetic, the doctor replied, “Vitamins should take Gertrude Lawrence.”) In the fall of 1939, Lawrence gave a reporter a rundown of her typical workday:

My day starts at 8 a.m. This usually shocks people when they hear it. The popular impression is that every actress sleeps until noon. So why do I get up so early? Well, I’ve loads to do. I have to exercise to keep in good physical condition, and then a quarter of an hour for massage of feet and ankles to keep these useful appendages slim and unweary. Then, breakfast in bed. But no ham or eggs or marmalade or pancakes. Just fruit and coffee. Next, the morning mail . . . fan letters, letters about plays, business matters and lastly of course social correspondence. I have a secretary to help me, but even so dictating an answer to every single letter takes oftentimes until noon. Of course, personal letters I answer by hand. Then, while my secretary is typing, I relax before lunch by arranging flowers. . . . When these are all beautifully arranged in bowls and vases, it’s usually lunch time. If there is half an hour to spare, my secretary and I play a game of chess. This is not only a splendid game but teaches you to concentrate. Lunch, which follows this busy morning, is a simple meal of vegetables and salad. Afterwards I sew for a while. I enjoy making old-fashioned samples, but usually there is not a very long time for this quiet occupation before my producer’s representatives call. They visit me every day to discuss the problems that naturally arise in every production. After they leave me there are usually some new scripts to be read. After this I take Mackie my Highland terrier for a walk, thus giving both of us the necessary daily exercise. If I have shopping to do or visits to make, this is the time I do it—but always when I’m playing I make it a rule to be home in time for two hours’ rest before going to the theatre, relaxing before the evening’s work and making up for too brief sleep at night. I don’t like to eat before I go to the theatre. After the performance I am usually very hungry, and I have a big meal usually with friends, for if I eat alone I seldom eat enough. It’s well after midnight before I am home again and ready to go to bed. And this is what people call a glamorous and romantic life. There may be glamour and romance about certain phases of it, but let’s nobody imagine that it isn’t mostly hard and tireless work. I travel too much to have a real home, and I always say that a new play takes a year off one’s life.

This description was from shortly before Lawrence married her second husband, the naval officer Richard Aldrich, who soon witnessed her pre- and post-performance rituals firsthand—and who discovered that Lawrence was indeed very hungry at the end of the night. He recalled, “At such times there was nothing she enjoyed more than steak tartare—the chopped raw beefsteak mixed with chopped green onion and a whole raw egg favored by stars of grand opera after an exhausting performance. With this she would drink a tankard of Canadian ale.” Aldrich was frankly shocked. His new bride—“the exquisite, ethereal creature” he and so many others admired onstage—could, he wrote, “put away a meal I had hitherto associated only with ponderous Brunhildes and the drivers of transcontinental trucks.”

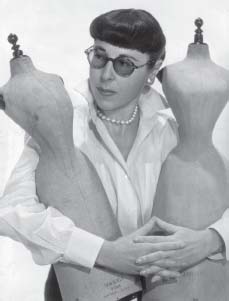

“To be a good designer in Hollywood, one has to be a combination of psychiatrist, artist, fashion designer, dress-maker, pin cushion, historian, nurse maid and purchasing agent too,” Head once said. She would know: Over her six-decade career, Head designed costumes for more than eleven hundred films, was nominated for forty-five Academy Awards (and won eight of them), and became a style icon in her own right, instantly recognizable by her short bangs, her monochrome two-piece suits, and the dark glasses she wore all the time, indoors and out. Head started out in Paramount Studios’ costume department as a twenty-six-year-old former schoolteacher, and worked her way up the ranks, eventually becoming the golden-age costume designer Travis Banton’s second-in-command. When Banton left Paramount in 1938, Head took over the department. “There was no fanfare, no dramatic transition, no popping of champagne corks, no raise in salary,” she remembered decades later. “I had been working six days a week, fifteen hours a day, and I continued this routine.” Through the 1930s and 1940s, she worked on thirty to forty films a year, often dressing all the stars, male and female, for four or five films at once.

She succeeded due to her artistry and work ethic, but also because of her skill at navigating the big personalities and hot tempers of a Hollywood production; indeed, Head said that she was “a better politician than I am a designer. I know who to please.” In an ideal world, she would have liked to be more of a perfectionist about her work, but the realities of Hollywood filmmaking simply didn’t allow it. “Inside I was a prima donna who insisted that a costume be made my way or not at all,” Head said; “outside I was the model employee, easy to get along with and always on time.” Working in Hollywood, she added, “I learned to suppress my artistic needs.”

As for her signature wardrobe, that, too, grew out of necessity. When she took over Paramount’s costume department, Head quickly grasped the importance of letting the actors be the absolute center of attention. “I never use color in the room in which I work or my offices or my fitting rooms,” she said.

And I never wear color myself. I mean never. I wear beige, occasionally gray (my favorite shade is a beigy-gray) or white or black. When I stand behind a glamorous star who’s fitting a glamorous dress, I don’t want to be an eye-catcher. I want the actors to concentrate on themselves. Any distraction such as pictures on the wall or the reflection of me in a very fashionable or brightly colored dress would only take their eye away from their image. I play down how chic I can look. An actor must be totally absorbed with how he or she appears.

Edith Head, circa 1955

“When I’m at the studio, I’m always little Edith in the dark glasses and the little beige suit,” she said on another occasion. “That’s how I survived.”

“Dietrich was not difficult; she was a perfectionist,” recalled Edith Head, who dressed the German actress for several films beginning in the late 1930s.

She had incredible discipline and energy. She could work all day to the point of exhaustion, then catch a second breath and work all night just to get something right. Once we worked thirty-six hours straight—from early Monday to late Tuesday—preparing a costume for her to wear on the set Wednesday night. . . . I was amazed at her stamina and determination.

Another costume designer who worked with Dietrich said that she “would come directly from the plane through the prop room and stand motionless for eight or nine hours a day in front of mirrors while we made the dresses on her.” She was equally a perfectionist about film makeup, lighting, and editing, the finer points of which she had absorbed through her intense collaboration with the director Josef von Sternberg, who brought her to international stardom with the 1930 film The Blue Angel and six subsequent films. Away from the studio, Dietrich hardly relented; she held any form of idleness in contempt. “It is a sin to do nothing,” she wrote. “There is always something useful to be done.” Around the house, she regarded cooking and housework as among “the greatest occupational therapies,” and went at them both with gusto. “The more plentiful the work,” she wrote, “the less time to be neurotic.”

Born in England to a long line of performers, Lupino moved to Hollywood in the 1930s and initially made her mark as a worldly-wise actress in such films as They Drive by Night, High Sierra, and The Sea Wolf. But Lupino “never really liked acting,” she once said. “It’s a torturous profession and plays havoc with your private life.” In 1949 she and her second husband founded an independent production company and Lupino began writing and directing a string of low-budget films that confronted such social taboos as rape, illegitimacy, and bigamy. In 1953, she released what may be her masterpiece, The Hitch-Hiker, a tense thriller considered the only film noir by a woman. In the subsequent decades, Lupino made only one more feature film, but she was a frequent director for the small screen, lending her talents to scores of television series, including Alfred Hitchcock Presents, Bewitched, Gilligan’s Island, and The Twilight Zone.

Of course sexism was an obstacle for Lupino, who tackled it through relentless professionalism. “As soon as I get a script I go to work on it,” she said. “I study and I prepare and when the time comes to shoot, my mind is usually made up and I go ahead, right or wrong.” Whenever possible, she would use the weekend to prepare for the week ahead. “I go out on the back lot or to the sets on Saturday and Sunday,” she said, “when it is nice and quiet, and map out my set-ups.” (As a writer, she was not quite so organized. According to the biographer William Donati, “Ida would sometimes write for twenty-four hours straight, scribbling on anything at hand, from odd bits of paper to grocery bags.”)

On set, Lupino also employed a calculated maternal façade; the cast and crew got into the habit of calling her Mother, a nickname she encouraged. “Keeping a feminine approach is vital,” she once explained.

Ida Lupino in her director’s chair, circa 1948

Men hate bossy females. You do not tell a man; you suggest to him. “Darlings, Mother has a problem. I’d love to do this. Can you do it? It sounds kooky, I know. But can you do this for Mother? And, they do it. That way I got more cooperation. I tried to never blow up. A woman cannot afford to do that. They’re waiting for it. . . . As long as you keep your temper, the crew will go along with you. I loved being called Mother.

Comden was one-half of the longest-running writing team in Broadway history; her sixty-year creative partnership with Adolph Green produced such hits as On the Town, Wonderful Town, Bells Are Ringing, and Peter Pan, and the duo also wrote the scripts for several Hollywood musicals, including 1952’s Singin’ in the Rain. Virtually every day, Comden and Green met in the living room of Comden’s Manhattan apartment to work on their next show, although their meetings didn’t always look much like work. “We stare at each other,” Comden said in 1977.

We meet, whether we have a project or not, just to keep up a continuity of working. There are long periods when nothing happens, and it’s just boring and disheartening. But we have a theory that nothing’s wasted, even those long days of staring at one another. You sort of have to believe that, don’t you? That you had to go through all that to get to the day when something did happen.

The idea for Bells Are Ringing took them, Green said, “a year of sitting around.” In interviews, they were sometimes pressed to describe their creative process in greater detail, to little avail. Comden once allowed that she tended to be the one who did the actual writing—on a pad of paper or, later, a typewriter—while Green paced about the room. But, she said, “at the end of the day we don’t know who contributed what idea or what line.”

Outsiders often assumed that Comden and Green were married to each other, but they were never romantically involved, and each enjoyed decades-long marriages to other people. (“Confusion still reigns,” Comden wrote in her memoir, Off Stage. “I always say as long as we are not confused, everything is all right.”) When asked what cemented their long working relationship, Green suggested the common element might have been hunger. Comden floated a different theory. “Sheer fear and terror,” she said.