“Somewhere along the line, one has to choose between the Life and the Project,” Sontag said in a 1978 interview. There was never any doubt in her mind about which was the right choice for her. Ever since discovering Modern Library books as a girl browsing a stationery and greeting-card store in Tucson, Arizona, Sontag was determined to escape “that long prison sentence, my childhood” for the world of the writers and intellectuals she idolized. “It never occurred to me that I couldn’t live the life I wanted to lead,” she said many years later. “It never occurred to me that I could be stopped. . . . I had this very simple view: that the reason people who start out with ideals or aspirations don’t do what they dream of doing when they’re young is because they quit. I thought, well, I won’t quit.”

Sontag wasted little time chasing her ideals. She graduated from high school at fifteen, entered the University of Chicago at sixteen, married at seventeen, and gave birth to a son a year and a half later. Her husband was a sociology instructor eleven years her senior, who proposed ten days after their first meeting. Although Sontag was initially thrilled with their life as university intellectuals, the marriage lacked passion, and in 1959 she ended it, moving with her seven-year-old son to New York to start over. Despite having very little money, Sontag refused alimony or child support. She took a temporary job as an editor at the journal Commentary, then a series of teaching jobs. Within a few years, she had published a novel and was writing the essays that would make her name.

Sontag succeeded, in large degree, thanks to her seemingly boundless energy: From the moment she arrived in New York, she wanted to read every book, see every movie, go to every party, have every conversation. One friend recalled, only half jokingly, that she “watched twenty Japanese films and read five French novels a week”; another said that, for Sontag, “aiming for a book a day was not too high.” Her son, David Rieff, later wrote: “If I had to choose one word to describe her way of being in the world it would be ‘avidity.’ There was nothing she did not want to see or do or try to know.” Sontag herself recognized the value of this avidity. “More than ever—and once again—I experience life as a question of levels of energy,” she wrote in her journal in 1970, adding a few paragraphs later: “What I want: energy, energy, energy. Stop wanting nobility, serenity, wisdom—you idiot!”

Sontag’s relentless curiosity helped give her writing its density of references and its unmistakable air of authority, but it also made it hard for her to actually sit down and write. Even though she believed that writing every day would be best, Sontag was never able to do so herself; instead, she wrote in “very long, intense, obsessional stretches” of eighteen or twenty or twenty-four hours, often motivated by an egregiously neglected deadline that she finally couldn’t ignore any longer. She seemed to need the pressure to build to an almost intolerable level before she could finally begin to write—largely because she found writing incredibly difficult. “I am not at all the kind of writer who writes very easily and very rapidly and only needs to correct or change a bit,” she said in 1980. “My writing is extremely painstaking and painful, and the first draft is usually awful.” The hardest part, she said, was to get that initial draft; after that, at least she had something to work with, and she would rework it many times, going through ten to twenty drafts, regularly taking months to complete a single essay. And she only got slower as time went on: It took Sontag five years to complete the six essays for her landmark 1977 book, On Photography.

Another obstacle for Sontag was simply being alone: She was an extremely gregarious person who loved conversation and had no real desire for solitude, a trait that she knew was bad for a writer. She said in 1987:

Kafka had a fantasy of setting up shop in the subbasement of some building, where twice a day somebody would put something to eat outside the door. He said: One cannot be alone enough to write. I think of writing like being in a balloon, a spaceship, a submarine, a closet. It’s going someplace else, where people aren’t, to really concentrate and hear one’s own voice. . . . It’s up to me not to answer the phone, or not to go out to dinner. I need a lot of turning inwards. It’s an effort to find that solitude, because I’m not actually a very reclusive person. I like being with people, and I don’t particularly like being alone.

Of course, when she was starting out, she wasn’t alone: Sontag wrote her first novel, The Benefactor, and her early essays while caring as a single parent for her young son—and also juggling several jobs, numerous romances, and her voracious cultural life. How did she manage it all? Partly it was by eschewing some of the traditional obligations of motherhood, such as cooking, which she never pretended was a priority. “I didn’t cook for David,” she joked with an interviewer in 1990. “I warmed for him.” (In another interview, she said that David “grew up on coats”—that is, the coats on the beds at all the parties she brought him along to.) As for her writing binges, Sontag later told the writer Sigrid Nunez that she simply made it work. “When I was writing the last pages of The Benefactor, I didn’t eat or sleep or change clothes for days,” Sontag said. “At the very end, I couldn’t even stop to light my own cigarettes. I had David stand by and light them for me while I kept typing.” (Nunez adds: “While she was writing the last pages of The Benefactor, it was 1962, and David was ten.”)

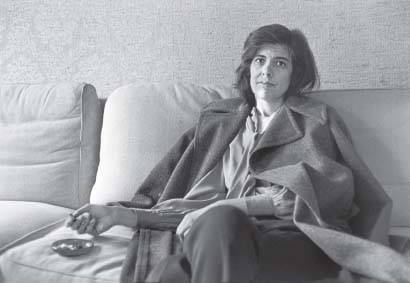

Susan Sontag, Paris, 1972

This was before Sontag began taking Dexamyl, an antidepressant medication that combined an amphetamine (to elevate mood) and a barbiturate (to counter the amphetamine’s side effects). According to Sontag’s son, she became dependent on Dexamyl for writing in the mid-1960s and continued using it until the 1980s, “though in diminishing doses.” She was open about the drug’s utility for a writer. In a 1978 interview, the magazine High Times asked Sontag if she ever used marijuana for her writing. “I use speed to write, which is the opposite of grass,” she replied. Asked what it did for her, Sontag said: “It eliminates the need to eat, sleep or pee or talk to other people. And one can really sit 20 hours in a room and not feel lonely or tired or bored. It gives you terrific powers of concentration. It also makes you loquacious. So if I do any writing on speed, I try to limit it.”

Sontag generally wrote first drafts by hand, lying stretched out on her bed, then moved to her desk to type up successive drafts on the typewriter or, later, the computer. Writing for her meant losing weight, it meant backaches and headaches and pains in her fingers and knees. Sontag talked about wanting to work in a way that was less physically punishing, but she never seriously tried to change her habits; she seemed to need the process to be a little self-destructive. “To write is to spend oneself, to gamble oneself,” she wrote in her journal in 1959, and she thought that it was only by pushing herself for long hours that she arrived at her best ideas. Besides, she had to admit that on some level she found it all “thrilling.” She liked to quote Noël Coward: “Work is more fun than fun.”

The American painter developed a remarkable ability to evoke natural landscapes through abstract compositions—“You have a feeling that her paintings show a location, even though you don’t know where it is,” the poet John Ashbery once observed—and yet she mostly painted at night, working by fluorescent light. Living in a one-room studio in New York’s East Village in the 1950s, Mitchell generally wouldn’t get up until the early afternoon and often wouldn’t start painting until sundown. She would prepare to work by lowering the needle on a record, usually jazz or classical music, played loud. The music made her “more available” to herself, Mitchell said—and it signaled to others that she “was in her ‘painting mode’ and was not to be disturbed,” one former neighbor recalled.

By then Mitchell would have had a few drinks; she started drinking at about 5:00 p.m. most days, steadily guzzling beer, Scotch, bourbon, gin, or Chablis—she wasn’t picky. But she was sensitive about the cliché of Abstract Expressionist painters drunkenly flinging paint onto their canvases, and according to the biographer Patricia Albers, “at least once she made a younger artist swear never to tell anyone that she or her colleagues touched a drink in the studio.” This was far from the truth; Mitchell once admitted to another friend that “if she did not drink she could not paint.”

Mitchell painted in fits and starts, making several decisive brushstrokes, then retreating from the canvas to the opposite end of the studio, looking at what she had done, changing the record, looking some more, and finally reapproaching the canvas for another few brushstrokes—or not. She progressed slowly, sometimes spending months on a single painting. “The idea of ‘action painting’ is a joke,” Mitchell said in 1991. “There’s no ‘action’ here. I paint a little. Then I sit and look at the painting, sometimes for hours. Eventually the painting tells me what to do.”

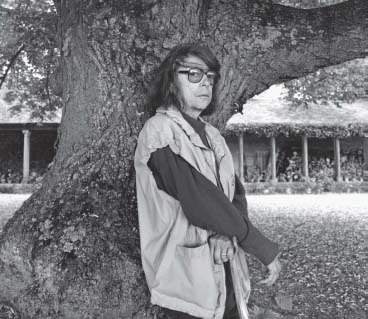

Joan Mitchell, Vétheuil, France, 1992

In 1959, after losing the lease on her East Village apartment, Mitchell moved to Europe with her companion Jean-Paul Riopelle, a Montreal-born painter. The couple settled in Paris for several years; then, in 1967, Mitchell used a modest inheritance from her grandfather to purchase a two-acre country estate in Vétheuil, a tiny village about thirty-five miles northwest of Paris. (Monet lived there in the 1870s, although Mitchell resented the association.) Mitchell, Riopelle, and their five dogs moved there in 1968. “How goes your work day, Joan?” a visiting critic asked her several years later. “Get up in the morning?” “Not always,” Mitchell answered with a laugh. She continued:

Lunch at one. With Hollis [her assistant and friend] or by myself. Afternoon, I do the crossword puzzle and listen to a couple of shrink programs. . . . People call up with their problems, and that sort of makes you feel better you don’t have that problem.

Then, winter, the light goes down around four-thirty. I dog-feed then, or I can’t see in the kennel. Later, in summer. Then Jean-Paul comes home around seven-thirty to nine for supper. We eat. Look at television. Then I might paint. Or I might not look at television—and paint. Ten to four I paint. Something like that. Except the bad times.

The bad times, Mitchell continued, were when she couldn’t feel anything, and “everything looks the same nocolor. I fight it. It’s not a cyclical thing—seems to be my water level. I don’t play around with it, though. I hear music, try to be active, walk to town. If I get into the work, then it’s not there. That’s the only fun I have. When I’m in it, I don’t think about myself.”

In 1981, she and Riopelle separated and Mitchell continued to live in Vétheuil alone, albeit with the companionship of her dogs and a steady stream of friends and visitors. Although Mitchell was notoriously prickly in person, she loved to entertain, hosting long, boozy dinners most nights. Afterward, she would wash the dishes and then walk—or stagger—to her studio, housed in a former game room directly behind the house, toting along, according to Albers, “her survival bag bulging with a jug of Johnnie Walker, two or three books of poetry, and perhaps a few letters.” The studio was her private sanctuary; she kept it locked at all times and slept with the key under her pillow. (When the studio toilet broke, she procrastinated on getting it fixed because she couldn’t bear to let the plumber inside.) It felt, one friend remembered, “like a place that an animal goes to for safety.”

In fact, it may have been the opposite—the place that a tough, combative artist went to let down her defenses and take risks. “No one can paint—write—feel whatever without being vulnerable,” she once said. And, she added, “one has to be very strong to be vulnerable.”

For Duras, writing was less a process of invention than of discovery—or, perhaps more accurately, of confrontation. Writing meant uncovering something that, she felt, already existed inside her unconscious, whole, waiting to be revealed. She found the process daunting, even terrifying—no doubt because her fiction often drew on her traumatic childhood. (Duras may be best known for her 1984 novel The Lover, about a fifteen-year-old French girl’s affair with an older, wealthy Chinese man—a barely fictionalized retelling of her own experience growing up in an impoverished family in French Indochina.) “It’s like a crisis I handle as best I can,” Duras said of her writing process. “It’s a kind of subjugation. When I’m writing I’m frightened; it’s as though everything were crumbling around me. Words are dangerous, physically charged with powder, poison. They poison. And then that feeling that I mustn’t do it.” Not surprisingly, writing wasn’t something she did regularly or on any kind of timetable; instead, when a book idea came to her, it obsessed her and took over her life. She wrote her 1950 novel The Sea Wall in eight months, “working at her desk without a break from five in the morning to eleven at night,” according to the biographer Laure Adler. At night she drank, seeking oblivion. “I’m a real writer, I was a real alcoholic,” she said in 1991, after she finally dried out for good. “I drank red wine to fall asleep. Afterwards, Cognac in the night. Every hour a glass of wine and in the morning Cognac after coffee, and afterwards I wrote. What is astonishing when I look back is how I managed to write.”

In the 1980s, Fitzgerald offered some writing advice to her son-in-law’s sister, who was trying to compose poetry while working as an administrator of a writers’ colony in West Yorkshire, England. “I hope you’ll be completely ruthless,” Fitzgerald told her, “take the best typewriter for yourself, neglect all the friends who come to stay, the hens, the course members, etc, in favour of the writing, otherwise it’s not possible to get it done.” Fitzgerald was writing from personal experience. She had been a star student at Oxford in the 1930s, and was widely expected to go on to a brilliant literary career; as it turned out, she didn’t publish her first book, a biography, until she was fifty-eight years old. Eleven more books—nine novels and two biographies—followed over the subsequent twenty years, and her last novel, The Blue Flower, made Fitzgerald an unlikely literary celebrity at age eighty. But in between Oxford and her first book there was a long period of family crises, financial strain, and drudgery, and for much of that time Fitzgerald pretty much resigned herself to never achieving her ambitions. “I’ve come to see art as the most important thing but not to regret I haven’t spent my life on it,” she noted to herself in 1969.

Initially, Fitzgerald’s writing career had looked bright. After graduation, she found work as a film and book reviewer, a BBC scriptwriter, and the coeditor, with her husband, of the monthly culture magazine World Review, for which she wrote numerous editorials and essays. But the Review folded, and her husband’s attempt to resume his delayed legal career fizzled; meanwhile, he began drinking heavily. By then the Fitzgeralds had three young children, and the family was living beyond its means; soon they found themselves hurtling toward poverty. In 1960, they moved onto a rickety houseboat moored in the Thames, the cheapest available housing option in London, although it proved just barely habitable—the barge was chilly and damp; as the tide rose it leaked, and as the tide went out it settled unevenly in the mud, putting their living quarters on a slope. It eventually sank, along with most of the family’s possessions.

The same year they moved onto the houseboat Fitzgerald began teaching to earn money, and she would continue to do so for twenty-six years, until she was seventy. She took up teaching because it was the obvious choice for a middle-aged woman with a good education and few other options, but she did not enjoy it. “Faced by piles and piles of foul A level scripts I have a sensation of wasting my life, but it’s too late to worry about this anyway,” she wrote in a letter from the time. In reality, she wasn’t quite as despairing as that letter makes it sound, or at least not all the time. A few years into her new career, Fitzgerald began to write in small spurts, making notes on the backs of student papers and filing drafts alongside her pupils’ exams, stealing time whenever she could—“during my free periods as a teacher in a small, noisy staff room, full of undercurrents of exhaustion, worry and reproach.”

But it wasn’t until 1971 that Fitzgerald was finally able to properly resume—or, really, begin—her literary career. She was fifty-four, and her youngest child was about to leave home; meanwhile, her rocky marriage had settled into a friendly companionship. For the first time in decades, Fitzgerald had the time and mental space to write. She began researching her first book, a biography of the Victorian painter Edward Burne-Jones, in the evenings after work, chiding herself for not having the energy to work even longer hours. “I’m very annoyed with myself that I can’t manage to do more in the evening,” she wrote to her daughter Maria in 1973. “All this dropping off must cease. After all I hardly ever go out so I should be able to get more done. One must justify one’s existence.”

It took her four years to finish the biography, but doing so unleashed a long-delayed outpouring. In the next five years she published six more books, including a series of short novels that drew on the trials of her middle age. (The Booker Prize–winning Offshore, for instance, is a fictionalized version of the family’s years aboard the ill-fated houseboat.) If she never quite felt that she had lived up to her full potential, she at least knew that she had found her proper subject matter as a novelist. “I have remained true to my deepest convictions,” Fitzgerald said in 1998. “I mean to the courage of those who are born to be defeated, the weaknesses of the strong, and the tragedy of misunderstandings and missed opportunities, which I have done my best to treat as comedy, for otherwise how can we manage to bear it?”

“I am basically and primarily a carver and the properties of stone and wood and marble have obsessed me all my life,” the English abstract sculptor said in 1961. Hepworth’s process began with the raw material on hand, and she came to her sculptural ideas by relating herself to the “life” in a piece of wood or stone. She always visualized the completed work before she started carving. “I think one goes around sort of brooding,” Hepworth explained in 1967. “And then suddenly it flashes into one’s mind complete.”

Hepworth did not see her working process as particularly magical or mysterious. “I have always thought of my profession as an ordinary work-a-day job,” she said, although she did allow that being an abstract sculptor is “emotionally exhausting work.” Hepworth usually worked an eight-hour day, and she felt that the longer she worked, the better the results. “You have to work long unbroken hours in order to see any real progress,” she once told a visiting interviewer. “A block of stone like this, for instance, will not look very much different until a great deal of time has been spent on its carving. I like to start work around eightish in the morning and keep going until about six in the evening.”

This was in 1962, when Hepworth was fifty-nine and her four children were grown. While she was raising the children, her working habits could never be quite so consistent. “I had to have a very strict discipline with myself so that I always did some work every day, even if it was only 10 minutes,” she said of the years when her children were young.

It’s so very easy to say “Well, today’s a bad day; the children aren’t well, and the kitchen needs scrubbing . . . but maybe it will be better tomorrow.” And then you say to yourself that it may be even better next week, or when the children are older. And then you lose touch with your development. I think the ideas can go on developing behind the scenes if you keep in close touch with what you are doing even if you have interruptions. You actually mature faster. You may do fewer carvings, but they could be maturing at the same rate as if you had all the time to work.

Barbara Hepworth at her studio, 1952

Indeed, Hepworth insisted that having children didn’t hold her back as an artist, and that she felt no resentment about their demands on her time. (It may have helped that Hepworth’s first and second husbands were also artists with flexible schedules, and were able to help with the child-rearing, at least to some extent.) “We lived a life of work and the children were brought up in it, in the middle of the dust and the dirt and the paint and everything,” Hepworth said. “They were just part of it.”

From 1939 until the end of her life, Hepworth lived and worked in St. Ives, Cornwall, near the southwestern tip of England, and she worked outdoors as often as the weather allowed, which was most of the year. “Light and space are the sculptor’s materials as much as wood or stone,” she said. She generally worked on multiple sculptures at a time, and as she grew older she employed several assistants to help her with the work, although she still carved daily right up until her death, at seventy-two, in an accidental fire at her studio. She compared sculpture to playing poker. “I don’t actually play cards, but I gamble fearfully on my work,” she said. “You have to play your hunch. You must have a passion, an obsession to do something. My idea is to play it hard. Nothing really matters except doing the next job.”

Bowen was an Australian painter who studied art in London, where she became friendly with the city’s literary avant-garde, including Ezra Pound, T. S. Eliot, and the novelist Ford Madox Ford, whom she fell in love with and married in 1918, when she was twenty-four and he was forty-four. The next year they moved to a cottage in rural Sussex, where Ford—already celebrated as the author of Ladies Whose Bright Eyes and The Good Soldier—resolved to make a living as a pig farmer, and where Bowen gave birth to a daughter in 1920. After a few years (and the utter failure of Ford’s farming ambitions), they fled the cold, wet winters for the south of France and, later, Paris. Throughout this time Ford wrote fiction, and for a year he edited the Transatlantic Review. Bowen, meanwhile, struggled to find time for painting while caring for their daughter and—far more wearying—attending to her husband’s many needs. Ford, Bowen later wrote, “had a genius for creating confusion and a nervous horror of having to deal with the results.” Bowen was the “shock absorber” in their relationship: She paid the bills, prevented Ford from learning the full extent of their debts, and shielded the sensitive writer from interruptions; when Ford was finishing a book, he required that no one speak to him or show him the mail until after he had finished his morning’s work. Despite all this, Ford wondered why Bowen could never work as steadily as he did. She wrote in her memoir, Drawn from Life:

Ford never understood why I found it so difficult to paint whilst I was with him. He thought I lacked the will to do it at all costs. That was true, but he did not realise that if I had had the will to do it at all costs, my life would have been oriented quite differently. I should not have been available to nurse him through the daily strain of his own work; to walk and talk with him whenever he wanted, and to stand between him and circumstances. Pursuing art is not just a matter of finding the time—it is a matter of having a free spirit to bring to it. Later on, when I had more actual free time, I was still very much enslaved by the terms of my relationship with Ford, for he was a great user-up of other people’s nervous energy. . . . I was in love, happy, and absorbed. But there was no room for me to nurse an independent ego.

For a time in Paris, Bowen and Ford managed to find a mutually beneficial work arrangement, sharing a studio with an upper platform where Ford could write while Bowen painted on the main floor below. During this time, their five-year-old daughter stayed with a governess in a cottage in Guermantes, about twenty miles outside Paris. She went to school there during the week, and Bowen and Ford spent the weekends with her, an arrangement that proved suitable to everyone, although Bowen missed her daughter terribly. But this period of peaceful coworking proved to be only an interlude; Bowen soon learned that Ford had been having an affair with a younger writer, a thirty-four-year-old unknown named Ella Lenglet (who, at Ford’s suggestion, adopted the pen name Jean Rhys; see here). Bowen and Ford separated in 1928, and despite the many complications that ensued, Bowen was finally able to concentrate on her painting; three years after their separation, she had her first solo exhibition. Unfortunately, money problems prevented Bowen from giving art her full attention for very long, and forced her to focus on commissioned portraits. By the time Bowen wrote her memoir in 1940, she could take some satisfaction in having carved out a career as a well-regarded painter, but she could not help but feel that she could have accomplished more had she not poured so much energy into others’ needs. “If you are a woman, and you want to have a life of your own, it would probably be better for you to fall in love at seventeen, be seduced, be abandoned, and your baby die,” she wrote. “If you survived this, you might go far!”

Chopin grew up in St. Louis, married at twenty, and moved with her husband to New Orleans, where he ran a cotton brokerage; over the next nine years, she gave birth to six children. In 1882, Chopin’s husband died of malaria, and a few years later she moved the family back to St. Louis, where she began writing fiction, publishing her first story in 1889 and her first novel, At Fault, in 1890. Over the next decade, she wrote approximately a hundred short stories, and gained an increasingly wide readership through publication in several national magazines, including The Atlantic Monthly and Vogue. Chopin never wrote to any kind of timetable, and she didn’t even keep a separate writing room; according to her daughter, she preferred to write with her children “swarming about her.” In an essay for the St. Louis Post-Dispatch from November 1899—six months after the publication of her most famous novel, The Awakening—Chopin addressed some common questions about her writing process:

How do I write? On a lapboard with a block of paper, a stub pen and a bottle of ink bought at the corner grocery, which keeps the best in town.

Where do I write? In a Morris chair beside the window, where I can see a few trees and a patch of sky, more or less blue.

When do I write? I am greatly tempted here to use slang and reply “any old time,” but that would lend a tone of levity to this bit of confidence, whose seriousness I want to keep intact if possible. So I shall say I write in the morning, when not too strongly drawn to struggle with the intricacies of a pattern, and in the afternoon, if the temptation to try a new furniture polish on an old table leg is not too powerful to be denied; sometimes at night, though as I grow older I am more and more inclined to believe that night was made for sleep.

According to the biographer Per Seyersted, Chopin “spent only an average of one or two mornings a week on the physical act of writing,” and by all accounts she wrote only when seized by inspiration. “There are stories that seem to write themselves,” Chopin said, “and others which positively refuse to be written—which no amount of coaxing can bring to anything.” Chopin’s son Felix observed firsthand how “the short story burst from her: I have seen her go weeks and weeks without an idea, then suddenly grab her pencil and old lapboard (which was her work bench), and in a couple of hours her story was complete and off to the publisher.” Chopin claimed that she made virtually no revisions, which she considered unnecessary and even counterproductive. “I am completely at the mercy of unconscious selection,” she wrote. “To such an extent is this true, that what is called the polishing up process has always proved disastrous to my work, and I avoid it, preferring the integrity of crudities to artificialities.”

Jacobs was born a slave in Edenton, North Carolina. After years of enduring the sexual predations of her master, she managed to escape to the North—but first she spent nearly seven years hiding in her grandmother’s house, in a nine-by-four-foot garret whose sloped ceiling reached three feet at its tallest point, and from which Jacobs could emerge only at night, for brief periods of exercise. This was but one of the harrowing experiences recounted in Jacobs’s autobiography, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, published under the pseudonym Linda Brent in 1861. Jacobs almost didn’t write the book; when the Quaker abolitionist Amy Post first suggested the idea, she resisted, loath to revisit her traumatic past. But Jacobs decided it was her duty to try to be “useful in some way” to the antislavery cause, and she set out to record her life.

The actual writing was not a problem; as a child, Jacobs was taught by her mistress to read, write, and sew. But finding the time to write was a serious challenge. By the 1850s, Jacobs was no longer a fugitive—her employer, Cornelia Willis, had purchased her freedom in 1852—but she was still obliged to work for a living, and was employed as the Willis family nursemaid, traveling with them between New York and Boston. In 1853, the year she started her book, the Willises relocated to Idlewild, their new estate in the Hudson River valley. There, Jacobs felt increasingly isolated, and she was exhausted by her twenty-four-hour-a-day, seven-day-a-week job caring for the Willis family’s five children, including a new baby born that summer. She could find the time to write only at night, while the children slept. “I have not yet written a single page by daylight,” she confided in a letter to Post, “. . . with the care of the little baby the big Babies and at the household calls I have but a little time to think or write.” In another letter she complained that if she “could steal away and have two quiet Months” to herself, she “would work night and day though it should all fall to the ground.” At other times, however, she struck a more sanguine tone: “The poor Book is in its Chrysalis state and though I can never make it a butterfly I am satisfied to have it creep meekly among some of the humbler bugs.”

Over the years, the book crept toward completion; by continuing to write “at irregular intervals, whenever I could snatch an hour from household duties,” Jacobs gradually recorded her life, and in March 1857, after four years of work, she finished the book. (Working on the preface, she noted that she had “been interrupted and called away so often—that I hardly know what I have written.”) Publication was another challenge, involving years of further work, and when the book finally came out, Jacobs’s story was overshadowed by the outbreak of the Civil War, and then largely forgotten for decades. Its rediscovery in the late twentieth century finally restored Jacobs’s autobiography to the stature it deserves, as a triumph of perseverance and truth-telling in the face of unimaginable adversity.

Marie and Pierre Curie announced the existence of polonium and radium in papers published in July and December 1898; to prove their discoveries beyond a doubt, they next set out to isolate the elements in their pure form. Over the course of their earlier research, the married scientists had hypothesized that pitchblende ore contained minute quantities of the new elements. But attempting to separate them from the pitchblende would require an arduous process. It was Marie who resolved to attempt it regardless of the difficulty; Pierre confided to a friend that he would never have done so on his own: “I would have gone another way,” he wrote. Many years later, Marie and Pierre’s daughter Irene (born the year before the Curies’ discovery) agreed that her mother was the motivating force behind the project. “One can discern,” Irene wrote, “that it was my mother who had no fear of throwing herself, without personnel, without money, without supplies, with a warehouse for a laboratory, into the daunting task of treating kilos of pitchblende in order to concentrate and isolate radium.”

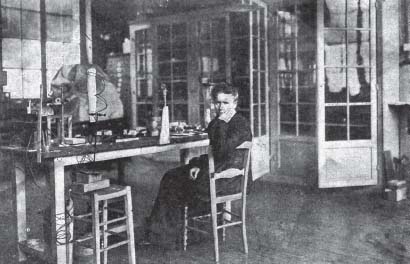

Marie Curie in her laboratory, Paris, 1913

The Curies’ lack of institutional support or adequate facilities has become legendary. After the Sorbonne declined their request for a workroom, the couple found a cavernous hangar at the school where Pierre taught; it was previously used as a dissection room by medical students, until it was deemed unfit even for that purpose. The space was barely furnished, the roof leaked, and the only source of heat was an ancient cast-iron stove. “It looked like a stable or potato cellar,” a visiting chemist wrote, “and if I had not seen the worktable with the chemistry equipment I would have thought it was a hoax.” But at least the hangar opened onto a courtyard, which proved indispensable for storing the tons of pitchblende residue the Curies ended up needing for their work.

From the beginning, Pierre concentrated on the physics side of the problem, while Marie took charge of the chemistry—which required periods of backbreaking labor. “I had to work with as much as twenty kilograms of material at a time,” she wrote, “so that the hangar was filled with great vessels full of precipitates and liquids. It was exhausting work to move the containers about, to transfer the liquids, and to stir for hours at a time, with an iron bar, the boiling material in the cast-iron basin.” In the early stages of the process, she sometimes spent the entire day standing over the boiling material, stirring it with an iron rod that weighed as much as she did; “I would be broken with fatigue at the day’s end,” she wrote.

Nevertheless, the Curies were content; it was “the heroic period of our common existence,” Marie wrote. “In spite of the difficulties of our working conditions, we felt very happy,” she later recalled. “Our days were spent at the laboratory. In our poor shed there reigned a great tranquility: sometimes, as we watched over some operation, we would walk up and down, talking about work in the present and in the future; when we were cold a cup of hot tea taken near the stove comforted us. We lived in our single preoccupation as if in a dream.”

In an 1899 letter to her sister, Marie elaborated on their daily routine during this period:

Our life is always the same. We work a lot but we sleep well, so our health does not suffer. The evenings are taken up by caring for the child. In the morning I dress her and give her her food, then I can generally go out at about nine. During the whole of this year we have not been either to the theater or a concert, and we have not paid one visit. For that matter, we feel very well.

The experiment proceeded with excruciating slowness. As the Curies entered their third year of work, money began running low. Pierre added another class to his teaching load and Marie became a physics professor at an academy for young women, with a ninety-minute commute each way, significantly reducing the time she could spend in the laboratory. Worried about their health, a friend and fellow scientist wrote to Pierre:

You hardly eat at all, either of you. More than once I have seen Mme. Curie nibble two slices of sausage and swallow a cup of tea with it. . . . It is necessary not to mix scientific preoccupations continually into every instant of your life as you are doing. . . . You must not read or talk physics while you eat.

The couple ignored his warning. Finally, after forty-five months of labor, Marie succeeded in isolating a decigram of pure radium and determining its atomic weight, officially proving the element’s existence. The following year the Curies were awarded the Nobel Prize for Physics (along with Henri Becquerel, who first discovered radioactivity). The Curies at first declined the invitation to deliver a speech in Stockholm, pleading too much work; however, in 1905, they reluctantly made the trip in order to claim the prize money, which they used to hire their first laboratory assistant. Although the money was helpful, the publicity unleashed by the Nobel announcement proved an unwelcome distraction for the Curies, who wanted only to continue their scientific work. Writing home to her brother the day after the Nobel ceremony, Marie said that they were continually beset by journalists and photographers, and inundated with invitations, which they always declined. “We refuse with the energy of despair,” she wrote, “and people understand that there is nothing to be done.”