The eighteen-year-old Bradstreet arrived in what is now Massachusetts in 1630, with her new husband, her father, and a group of their fellow Protestant dissenters, among the first wave of settlers in the New World. Two years later she wrote her first poem, “Upon a Fit of Sickness,” while convalescing from a long illness. The following summer Bradstreet became pregnant, and for the next six years she would not pen another line. But from 1638 to 1648, Bradstreet wrote more than six thousand lines of poetry—as the biographer Charlotte Gordon notes, “more than almost any other English writer on either side of the Atlantic composed in an entire lifetime.” And, Gordon continues, “for most of this time, she was either pregnant, recovering from childbirth, or nursing an infant.” (Bradstreet eventually had eight children.) The poet thought about her verse throughout the day, while minding the children, cooking family meals, or supervising the one or two female servants who performed the heaviest household chores—but she wrote exclusively at night, while the family and servants slept, the only hours when she could be alone. As she wrote in a letter, “The silent night’s the fittest time for moan.”

The only complete record of Dickinson’s daily routine comes from a letter she sent to a friend in November 1847, when she was a sixteen-year-old student at Mount Holyoke Female Seminary, seven miles from her home in Amherst, Massachusetts. “I will tell you my order of time for the day, as you were so kind as to give me your’s,” Dickinson wrote.

At 6. oclock, we all rise. We breakfast at 7. Our study hours begin at 8. At 9. we all meet in Seminary Hall, for devotions. At 10¼. I recite a review of Ancient History, in connection with which we read Goldsmith & Grimshaw [a pair of history textbooks]. At .11. I recite a lesson in “Pope’s Essay on Man” which is merely transposition. At .12. I practice Calisthenics & at 12¼ read until dinner, which is at 12½ & after dinner, from 1½ until 2 I sing in Seminary Hall. From 2¾ until 3¾. I practise upon the Piano. At 3¾ I go to Sections, where we give in all our accounts of the day, including, Absence—Tardiness—Communications—Breaking Silent Study hours—Receiving Company in our rooms & ten thousand other things, which I will not take time or place to mention. At 4½, we go into Seminary Hall, & receive advice from Miss. Lyon in the form of lecture. We have Supper at 6. & silent-study hours from then until retiring bell, which rings at 8¾, but the tardy bell does not ring untl 9¾, so that we dont often obey the first warning to retire.

Although the letter provides a vivid portrait of student life at a nineteenth-century New England religious school, it does not reveal much about Dickinson’s personality, and nothing about her eventual habits as a writer. Regretfully, no such detailed account of Dickinson’s writing day exists. It’s not even known exactly when Dickinson began composing poetry, although it was certainly by 1858, when the twenty-eight-year-old embarked on a project to recopy and organize her existing poems into small, hand-sewn booklets. These were not for distribution—Dickinson frequently enclosed individual poems or fragments of poems in her letters, but she did not share her eventual forty booklets with anyone, and they were discovered only after her death. Nor did she write with the idea of publication in mind, noting in a letter that it was “foreign to my thought, as Firmament to Fin.” Only ten of her nearly eighteen hundred poems were published in her lifetime, none of them at her instigation.

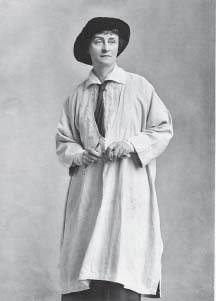

Emily Dickinson, circa 1846–47

As for what is known of Dickinson’s writing habits, evidence suggests that she wrote mostly at night—both letters and poetry—while the rest of the household slept. Except for the year she spent at Mount Holyoke, Dickinson always lived with her family, which comprised her conservative, overprotective father; her anxious, sickly mother; a sister who never married; and a brother who married in 1856 and moved to an Italianate mansion next to the Homestead, the large brick Federal house Dickinson’s grandfather had built, and where the poet lived for the first nine years of her life and from 1855 to her death. (In between, financial difficulties forced her father to sell his portion of the house, but he was later able to repurchase the entire property.) There, her large upstairs bedroom had windows looking out over Main Street and toward the Evergreens, her brother’s residence a few hundred yards away. The room had a small writing table in the corner and a Franklin stove to keep Dickinson warm on chilly nights while she wrote by candlelight.

Famously, after 1865 Dickinson was housebound, rarely or never leaving the grounds of the Homestead. It is possible that she suffered from agoraphobia, or that an eye ailment in the 1860s prompted her seclusion; Dickinson’s sister suggested, however, that it was their mother’s illness in the years leading up to 1865 that contributed to the poet’s withdrawal: “Our mother had a period of invalidism, and one of her daughters must be constantly at home; Emily chose this part and, finding the life with her books and nature so congenial, continued to live it.” Whatever the reason, it is true that Dickinson found her seclusion congenial; she enjoyed a rich private world concentrated on her reading and writing, and a wide-ranging correspondence. She still interacted with her family daily and took part in the household chores (apparently, baking and dessert-making were her special province). She avoided most visitors but would occasionally receive a guest at home, and she spent hours tending her spacious garden, although she was known to bolt indoors if any adults approached. Children, however, she welcomed, gardening peacefully while they played nearby—or, if she was in her room, silently lowering from her window a basket of gingerbread for them to enjoy.

Visitors who did get to meet “the myth,” as locals took to calling her, remember Dickinson as soft-spoken and childlike in demeanor, but with a strange intensity. After years of correspondence with Dickinson, the critic and scholar Thomas Wentworth Higginson visited her at the Homestead for an hour in August 1870. Years later, he recalled, “The impression undoubtedly made on me was that of an excess of tension, and of an abnormal life.” The day after his meeting, he wrote in a letter to his wife: “I never was with any one who drained my nerve power so much. Without touching her, she drew from me. I am glad not to live near her.”

To write, Dickinson seemed to need to harness that nervous energy, which she could not do on command. As a result, she wrote in waves of literary activity rather than through any kind of everyday practice. In her most fertile period, from 1862–63, she composed hundreds of poems; then, for years, she hardly wrote at all. As she said in an 1862 letter, “I had no Monarch in my life, and cannot rule myself, and when I try to organize—my little Force explodes—and leaves me bare and charred—”

“I am as busy as a whole hive of bees, one bee is not sufficient to represent all the irons I have in the fire,” the American neoclassical sculptor wrote from her studio in Rome in 1870. Ever since arriving in the Eternal City as an eager apprentice eighteen years earlier, Hosmer had been perpetually at work, sculpting most days from dawn until dinner. “She was never idle,” her friend Cornelia Carr remembered. “Her busy brain was unceasingly at work on favorite designs, and she was happy in plans for future activity.” Her dedication did not leave much time for a personal life; indeed, Hosmer swore off any romantic attachments at a young age, believing that they were too compromising for a female artist. “I am the only faithful worshipper of Celibacy, and her service becomes more fascinating the longer I remain in it,” she wrote in the summer of 1854, four years after arriving in Rome. “Even if so inclined, an artist has no business to marry. For a man, it may be well enough, but for a woman on whom matrimonial duties and cares weigh more heavily, it is a moral wrong, I think, for she must neglect her profession and her family, becoming neither a good wife and mother nor a good artist. My ambition is to become the latter, so I wage an eternal feud with the consolidating knot.”

Trollope married at thirty and, over the next nine years, gave birth to four sons and three daughters. Meanwhile, her husband failed first as a lawyer and then as a farmer, and the family’s financial situation grew dire. In an effort to forestall destitution, Trollope, her husband, and their three youngest sons sailed to America, where they helped to establish a utopian colony in Memphis and opened a bazaar for fancy imported goods in Cincinnati. Neither venture made any money, and after three years the family returned to England—but the trip planted the seed of a much more lucrative enterprise. While still in America, Trollope began making notes for a travelogue, on the hunch that her fellow British citizens would enjoy reading about the “so very queer” people in the New World. She was right; when it was published in 1832, Domestic Manners of the Americans was a best seller. With its success, Trollope had found her calling, and over the next twenty-five years she would publish five more travelogues and thirty-four novels.

Two of Trollope’s sons also grew up to become writers: Thomas Adolphus Trollope published more than forty volumes of travel writing, history, and fiction, and Anthony Trollope became one of the great novelists of the Victorian era, with forty-seven novels and many volumes of short stories, biography, and reportage. Anthony also became famous for his industriousness, writing for three hours every morning before going to his day job as a civil servant at the General Post Office (and, if he finished a book during his morning writing stint, immediately taking out a clean sheet of paper and beginning the next book). But he was merely doing his best imitation of his mother, who had set a high bar. “Of the mixture of joviality and industry which formed her character, it is almost impossible to speak with exaggeration,” Anthony wrote in his Autobiography. “The industry was a thing apart, kept to herself. It was not necessary that any one who lived with her should see it. She was at her table at four in the morning, and had finished her work before the world had begun to be aroused.” After that point, Trollope resumed her duties as the family matriarch, running the household (with the help of a pair of servants) and attending to the needs of her husband and children. Nevertheless, according to Anthony, she always remained cheerful in the face of her myriad responsibilities. “She had much, very much, to suffer,” he wrote. “Work sometimes came hard to her, so much being required . . . but of all people I have known she was the most joyous, or, at any rate, the most capable of joy.”

Often cited as the first female sociologist, Martineau was also one of the first female journalists. Over her long career, she produced countless essays on economics and social theory, as well as travel writing, an autobiography, and several novels—her best known is 1839’s Deerbrook—and she earned enough money to support herself solely by writing, a rare feat for a woman in Victorian England. Naturally, she worked incredibly hard. “From the age of fifteen to the moment in which I am writing, I have been scolded in one form or another, for working too hard,” Martineau noted in her autobiography. But the fact was, she continued, that she “had no power of choice” when it came to her intellectual labor: “I have not done it for amusement, or for money, or for fame, or for any reason but because I could not help it. Things were pressing to be said; and there was more or less evidence that I was the person to say them.”

This makes it sound as though Martineau never suffered from a moment of writer’s block; in fact, the opposite was the case. It was only her intimate experience with being blocked, and her realization of how to overcome that miserable state, that had enabled her to write so much. “I can speak, after long experience, without any doubt on this matter,” she wrote in her autobiography.

An engraving of Harriet Martineau, circa 1873

I have suffered, like other writers, from indolence, irresolution, distaste for my work, absence of “inspiration,” and all that: but I have also found that sitting down, however reluctantly, with the pen in my hand, I have never worked for one quarter of an hour without finding myself in full train; so that all the quarter hours, arguings, doubtings, and hesitation as to whether I should work or not which I gave way to in my inexperience, I now regard as so much waste, not only of time but, far worse, of energy. To the best of my belief, I never but once in my life left my work because I could not do it: and that single occasion was on the opening day of an illness.

This discovery came as a tremendous relief—merely by forcing herself to work for those first fifteen minutes, Martineau found that she was spared from “those embarrassments and depressions which I see afflicting many an author who waits for a mood instead of summoning it,” and from then on she could write whenever she chose.

As for her writing hours, Martineau was (perhaps not surprisingly) a devoted morning person. “I never pass a day without writing; and the writing is always done in the morning,” she wrote. In London, her typical schedule was to get up and make coffee at 7:00 or 7:30 a.m. and go immediately to work, which she continued until 2:00 p.m. (In her descriptions of her day, there is no mention of lunch.) Then she received visitors at home for two hours before going out for a one-hour walk. Returning home, she changed into evening dress and read the newspaper. Then a friend’s carriage would arrive to take Martineau to dinner and one or two evening visits. She tried to get home by midnight or half past, in order to answer letters or read before going to bed at 1:00 or 2:00 a.m. This means that on an average day she wrote for five and a half or six hours and slept the same amount at night. But after her morning coffee, Martineau did not drink any additional caffeine during the day, and she was dismissive of the popular idea that most writers relied on caffeine or alcohol or opiates to fuel their working hours. “Fresh air and cold water are my stimulants,” she said.

“Writers, like teeth, are divided into incisors and grinders,” the nineteenth-century English journalist Walter Bagehot once wrote. Hurst fell decisively into the latter group. Although she published more than three hundred short stories during her lifetime, as well as nineteen novels and several plays—making her one of the most widely read female authors of the twentieth century, and one of the highest-paid American writers of either sex—Hurst never found the writing process congenial. In her autobiography, she wrote of “that stubborn hiatus between the idea and the written word. The concept lively and boiling in my mind, the words coming in slow and painful trickle onto paper, there to torture with their inadequacies.” She continued, “That monkey on my back has never relinquished hold in all the years. The urge to write versus the torturous process of getting it said.” Despite the torture, Hurst wrote for several hours a day, every day, for pretty much her entire adult life. “My own workaday routine, five to six to seven hours at the desk, holds with the years,” she wrote. “Like woman’s work, the author’s work is never done.”

Post became a household name following the publication of Etiquette, her 1922 bible of proper social conduct, which she updated twice a decade for the rest of her life while also writing a syndicated newspaper column and answering a ceaseless influx of letters from readers seeking her advice on all manner of household, workplace, and polite-society dilemmas. Fortunately, Post liked to work. “We used to tell her that when she had a job in hand she was like a bird dog on a scent,” her son, Ned, wrote in a biography of his mother.

Throughout her life, Post woke at 6:30 a.m. and, while still in bed, set immediately to the day’s tasks, continuing to work without pause until noon. Her son writes:

She had improvised an arrangement which enabled her to get her own breakfast as early as she wished and while remaining in bed. A thermos of hot coffee, another small one of cream, butter in an iced container, zwieback and the dark buckwheat honey she loved were placed on a tray on her bedside table every night. She would breakfast and then, remaining in bed, write, edit copy, and plan her correspondence against the time her secretary would arrive. No telephone calls, no visitors, no household interruptions were permitted to break in on her working time. After twelve she rose, dressed, and was ready and hungry for luncheon punctually at one.

She preferred to have friends come to her to having lunch at other houses or at the Colony Club of which she was a charter member. She flatly refused to lunch in restaurants. She liked to drive in the afternoon, but would never consent to having a car of her own. She welcomed a guest or two at tea, which was always a part of her day’s ritual, and she frequently had guests for dinner, or dined out with friends of old standing and at houses where conversation flourished. She did not play bridge and she hated gossip and never indulged in it.

The reason Post refused to dine in restaurants was because she ate extremely rapidly, devoting no more than ten to fifteen minutes to mealtimes when she was at home; anything more, she felt, was a waste of her work hours. Of course, it helped that Post was always able to employ several domestic servants, and never had to prepare meals herself, something she was more or less incapable of. (The breakfast tray described by her son was prepared by the household staff the night before.) As Post once admitted to an interviewer, “If I were forced to cook for myself, my diet would be bread and water.”

Scudder was an Indiana-born sculptor whose whimsical fountains and statues became hugely popular in the early twentieth century, championed by the Beaux-Arts architect Stanford White and installed in the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the gardens of John D. Rockefeller and other members of the wealthy elite. Before achieving this success, however, Scudder endured an arduous apprenticeship, with studies in Cincinnati, Chicago, and Paris, and a period of near poverty in New York as she sought out commissions from architects and other clients. In her autobiography, Modeling My Life, Scudder describes her first summer in New York, when she was a twenty-six-year-old unknown living alone in a shabbily furnished studio on Union Square that she rented for fourteen dollars a month:

These long hot days began with a frugal breakfast—milk and bread; then I would put the studio in order, removing all traces of the bedroom it was at night and turning it into a workshop. The rest of the morning I usually spent in drawing, though many mornings I felt I should profit more by looking at the work of others and tramped up to the Metropolitan Museum, where I spent hours in studying the sculpture and in painting. . . . At lunch time I returned to the studio and prepared the simple meal that never varied and that did not take any time or skill to prepare—a can of baked beans and a glass of milk. I had heard that there was a great deal of nourishment in beans; at any rate I found them the most filling thing I could buy for fifteen cents. In the afternoon I went about from one architect’s office to another’s—always with hope and always in vain. . . . After an afternoon of rebuffs, footsore, hot and weary, I would usually—not every day but almost every other day—drop into a friendly little restaurant on Sixth Avenue, where, for twenty-five cents, I could have dinner, my only square meal. And it was square, there is no doubt about that—all put on the table at once, from soup to ice cream, each little dab in its own bird-bath dish, the meat growing cold and the ice cream melting before I could finish the soup. On those evenings when I felt twenty-five cents was too much to spend on dinner—having already wasted ten cents on street cars that day—I would dine in my studio on the same old menu of baked beans and milk. But the hardest part of the day to get through was the long summer evening. Can anything be more utterly dismal than a summer evening in a city without a soul to speak to! If the air was unbearably stifling, I would often wander out to Union Square and sit there on a bench for an hour or two—which invariably increased my depression and loneliness. Those other benches were filled with derelicts and loafers—the failures of life. I was too young then to feel any surge of sympathy towards them; they only filled me with disgust and an even greater desire for work—hard, satisfying work that would fill my empty life to overflowing. When I could stand it no longer I would leave the bench, walk slowly back to the studio and creep into my couch bed without turning on the light.

Janet Scudder, circa 1920

Scudder’s perseverance eventually paid off. Through the father of a wealthy art-school friend, she landed a commission to design the seal for the New York Bar Association, which opened the door to other jobs—and to a more congenial diet. Scudder wrote in her autobiography, “I can never see a tin of baked beans now without having an alarming sinking sensation.”

For decades, Bernhardt was the most famous actress in Europe, lauded by critics, greeted by adoring crowds wherever she went, and endlessly discussed in the press, which tracked her every movement and dubbed her the Eighth Wonder of the World. After watching her perform in London in 1880, the American psychologist William James wrote to his wife that “Bernhardt last night was the finest piece of acting I’ve ever seen—as if etched with the point of a needle—and altogether she is the most race-horsey, high-mettled human being I’ve ever seen—physically she is a perfect skeleton.” Bernhardt’s notorious thinness was only one part of her legend. There was also the ornate rosewood coffin that she was said to sleep in, and which she supposedly carried along on tour (in fact, she did keep such a coffin as a macabre set piece in her bedroom but did not normally sleep in it); the hat she wore festooned with a pair of leathery bat wings, and the stuffed vampire bat that she kept in her bedroom, along with a human skeleton and the aforementioned coffin; the pet alligator that she acquired while on tour in America, and which she named Ali-Gaga; and her insistence on being paid only in gold coins, which she carried around in an old chamois leather bag or a small suitcase, from which she reluctantly doled out payments to her performers, her servants, and her creditors. Although she hated to part with a single coin, she spent lavishly on her household, employing eight to ten servants, two carriages, and several horses, and constantly hosting luxurious dinner parties at which she herself ate virtually nothing.

Sarah Bernhardt posing in her coffin, circa 1873

But to her contemporaries in the theater Bernhardt’s most striking characteristic was her prodigious, seemingly unlimited energy, which allowed her to work around the clock without ever appearing to tire. “No person I have ever known had such amazing energy as Bernhardt,” the theatrical producer George Tyrell said. “Something seemed to burn within her like a consuming flame, which at the same time did not burn her out. The more she did the more inspiration she found.” In 1899, the poet and dramatist Edmond Rostand—whose play L’Aiglon gave Bernhardt one of her signature roles—described the actress’s typical workday, starting with her afternoon arrival at the theater:

A brougham stops at a door; a woman, enveloped in furs, jumps out, threads her way with a smile through the crowd attracted by the jingling of the bell on the harness, and mounts a winding stair; plunges into a room crowded with flowers and heated like a hothouse; throws her little beribboned handbag with its apparently inexhaustible contents into one corner, and her bewinged hat into another; takes off her furs, and instantaneously dwindles to a mere scabbard of white silk; rushes on to a dimly lighted stage and immediately puts life into a whole crowd of listless, yawning, loitering folks; dashes backward and forward, inspiring every one with her own feverish energy; goes into the prompter’s box, arranges her scenes, points out the proper gesture and intonation, rises up in wrath and insists on everything being done over again; shouts with fury; sits down, smiles, drinks tea, and begins to rehearse her own part. . . .

According to Rostand, these rehearsals could draw tears from the other actors who paused to watch Bernhardt—but the remainder of her pre-show ritual was more likely to draw groans of frustration from the theater’s crew, whom Bernhardt relentlessly pestered and bullied in her manic rounds backstage, making the decorators redo their work to her liking, showing the costumier exactly how to dress her, supervising the lighting artists’ work and reducing the electrician to “a state of temporary insanity.” Finally, Rostand continues, Bernhardt

returns to her room for dinner; sits down to table, splendidly pale with fatigue; ruminates over her plans; eats with peals of Bohemian laughter; has no time to finish; dresses for the evening performance while the manager reports from the other side of the curtain; acts with all her heart and soul; discusses business between the acts; remains at the theater until after the performance, and makes arrangements until three o’clock in the morning; does not make up her mind to go until she sees her staff respectfully endeavoring to keep awake; gets into her carriage; huddles herself into her furs and anticipates the delights of lying down and resting at last; bursts out laughing on remembering that someone is waiting to read her a five-act play; returns home, listens to the piece, becomes excited, weeps, accepts it, finds she cannot sleep and takes advantage of the opportunity to study a part!

“This is the Sarah I have always known,” Rostand concludes. “I never made the acquaintance of the Sarah with the coffin and the alligators. The only Sarah I know is the one who works.” Bernhardt must have appreciated the homage. “Life engenders life,” she once said, “energy creates energy. It is by spending oneself that one becomes rich.”

One of the great actresses of Edwardian England, Campbell had no real interests outside the theater, which didn’t leave her much time for them anyway. “The life of the stage is a hard one; the sacrifices it demands are enormous,” she wrote. “Peaceful normal life is made almost impossible by the ever over-strained and necessarily over-sensitive nerves—caused by late hours, emotional stress, swift thinking, swift feeling. . . .” Campbell’s dedication to her profession could make her a difficult collaborator; no one who worked with her was unfamiliar with “the exacting perfectionism, the terrible sarcasms, the bursts of fury, the will that dominated and dwarfed everyone around her,” in the words of the biographer Margot Peters. Away from the theater, Campbell’s perfectionism was toned down only slightly; at home, she aspired to simple bourgeois comforts for herself and her two children, and she could grow cross when this vision proved elusive. “Her neatness amazed me,” one acquaintance remembered. “Somehow one expected so great an artist to be careless about detail, but she was meticulously neat in all her habits. Domestic details maddened her, and I can see her now, entering [her daughter’s] bedroom, her great tragic eyes smouldering, and declaiming passionately—‘They tell me there is no more toilet paper in the house. How can I be expected to act a romantic part AND remember to order TOILET PAPER!’ ”