Frame was the New Zealand author of twelve novels, four collections of short stories, one collection of poems, and a three-volume autobiography. She grew up one of five children in a working-class family on New Zealand’s South Island, studied at the local college of education, and initially found work as a teacher, but after a suicide attempt she was committed to a mental institution and subsequently misdiagnosed as schizophrenic. Frame spent the better part of the next eight years in and out of various psychiatric facilities, where she underwent two hundred electroshock treatments. Nevertheless, she managed to write fiction with increasing dedication, and published her first book, The Lagoon and Other Stories, in 1951, while she was a patient at Seacliff Lunatic Asylum. There, she was scheduled to have a lobotomy, but when Frame’s doctors learned that her book had won New Zealand’s most prestigious literary prize, the procedure was called off. Instead, she was released.

From Seacliff, Frame went to stay with her sister, who took her to visit Frank Sargeson, a well-known local writer. Impressed by Frame’s stories, Sargeson offered to let her stay in an army hut behind his cottage and helped arrange for her to receive state medical benefits. About a month after being released from Seacliff, Frame moved onto Sargeson’s property and suddenly found herself a full-time writer. “I had an army hut containing a bed, a built-in desk with a kerosene lamp, a rush mat on the floor, a small wardrobe with an old curtain strung in front, and a small window by the head of the bed,” she wrote in the second volume of her autobiography. “Mr Sargeson (I was not yet bold enough to call him Frank) had already arranged for a medical certificate and a benefit of three pounds a week which was also the amount of his income. I thus had everything I desired and needed as well as the regret of wondering why I had taken so many years to find it.”

Frame quickly adapted herself to Sargeson’s daily routine, although she couldn’t break herself of the Seacliff habit of getting up very early and dressing immediately. “He did not get up until half-past seven, with breakfast at eight, and it seemed hours before I could pluck up courage to go up to the house with my chamberpot and my washing things, waiting until he was up and dressed,” she wrote.

Usually I helped myself to my own breakfast of a yeast drink brewed overnight, home-made curds topped with honey, and bread and honey and tea. If Mr Sargeson had breakfast with me, sitting on his side of the counter, I was inclined to chatter. Within the first week of my stay he drew attention to this. “You babble at breakfast,” he said.

I took note of what he said and in future I refrained from “babbling,” but it was not until I had been writing regularly each day that I understood the importance to each of us of forming, holding, maintaining our inner world, and how it was renewed each day on waking, how it even remained during sleep, like an animal outside the door waiting to come in; and how its form and power were protected most by surrounding silence. My hurt at being called a “babbler” faded as I learned more of the life of a writer.

After breakfast, Frame returned to her hut to work on her first novel, Owls Do Cry. At 11:00 a.m., Sargeson would come out with a cup of tea and a rye wafer spread with honey; after tapping gently on the door, he would enter the hut and leave the tea things on Frame’s writing table, respectfully “averting his gaze from the nakedness of my typed pages,” she wrote. As soon as he was gone, she “seized” the tea and wafer, then continued working until 1:00 p.m., when Sargeson would again come tap on the door to let her know that lunch was ready. At lunch, the older writer would read aloud from a book, “and discuss the writing while I listened, accepting, believing everything he said, full of wonder at his cleverness,” Frame wrote.

Frame did not settle in Sargeson’s hut permanently—after sixteen months, she received a grant that allowed her to travel to Europe, where she lived and worked for the next several years—but the routine she established there served her well throughout her life, as did the habit she adopted of tracking her day’s writing progress in an exercise book, in which she ruled columns for the date, the number of pages she hoped to write, the number of pages she actually wrote, and a column titled “Excuses.” Later in her career, she eliminated the last column and instead tracked her “Wasted Days”—as, she wrote, “I did not need to identify the known excuses to myself.”

Frame went on to win dozens of literary awards, but she did not become truly famous until the filmmaker Jane Campion adapted Frame’s autobiographies into the 1990 film An Angel at My Table. After Frame’s death, Campion wrote about visiting the writer in her New Zealand home in order to ask for the rights to her autobiographies. “Frame was not like anyone else I had met: she seemed freer, more energized, and absolutely sane,” Campion wrote.

I remember her house as being a bit of a mess: the kitchen was cluttered with dishes, and there was no door on the bathroom, just a curtain. She had a glamorous white Persian cat that we stroked and admired. Later she took me through the house and showed me how she worked. Each room and even parts of rooms were dedicated to a different book in progress. Here and there she had hung curtains to divide the rooms like they do in hospital wards to give the patients privacy. On the desk where she had last been working was a pair of earmuffs.

Frame told Campion that she couldn’t “bear any sound”—hence the earmuffs, and also the extra layer of bricks Frame had put on the front wall of her bungalow, in a futile attempt at soundproofing. Campion later used the earmuffs in her film; in the final scene, Frame is shown writing in a trailer in her sister’s backyard, donning earmuffs to block out the noise of her sister’s children playing outside. It is a fitting image for the writer, who was never entirely comfortable in society but found meaning and direction in her writing. “I think it’s all that matters to me,” she once told Frank Sargeson. “I dread emerging from it each day.”

For Campion, the long process of realizing a film almost always begins with writing; the New Zealand–born filmmaker has written or cowritten the screenplays for five of her seven feature films, as well as for her TV series Top of the Lake. In interviews, she has described this as a largely intuitive process. “It starts with a feeling that’s quite unnameable,” Campion said in 1993. “And a mood, you know? And then you try to write things that create the mood you are feeling or thinking of.” If the process works, then ultimately “the film is the mood,” she said.

When Campion was starting to write the screenplay for her 1993 film The Piano, she spent a week alone, wallowing in the mood of the story and the mind-set of her protagonist, occasionally bringing herself to tears in the process. “I have to spend a few days in it,” she said, “and then once I’ve got it, I can . . . go out and work more sort of from a nine to five basis.” But even then her writing process remains fragile and easily disrupted. “Sometimes I’m having a really inspired time, I’m really feeling like I’m penetrating some ideas, I’m working and working,” she said in 1997. “Then I get hungry or tired, and I think, Fuck it, if only I could have gone on for another hour, I could have got somewhere!”

Varda is often called the grandmother of New Wave cinema, a description that feels appropriate now that she is past ninety and has made twenty-one feature films and more than a dozen shorts; but when the label was first applied, Varda was barely thirty and hardly considered herself an Old Master of cinema. When she made her first film, 1954’s La Pointe Courte, Varda later protested, she had seen only five movies in her entire life. La Pointe Courte was, in fact, originally intended to be a novel. “But I drew pictures by way of an outline and I showed these to a man who was an assistant film director,” she said in 1970. “He suggested to me that cinema might be the ideal medium. And so I went ahead with some money that I had borrowed.” In the same interview, Varda described her filmmaking motivations as “an underground river of instincts.”

It took Varda seven years to make her next film, Cleo from 5 to 7, “not because I was a woman, but because I was writing the kind of films that are difficult to set up financially,” she said. But Varda was also vocal about the difficulties facing women in the cinema, as in any male-dominated profession. “There are two problems—the problem of the promotion of women in all professions in equal number to men, and the problem of society: how can women who still want to have children be sure to be able to have them when they want, with whom they want, and how are we going to help them raise the children,” Varda said in 1974. As for herself, she added, “there is only one solution and that is to be a kind of ‘superwoman’ and lead several lives at once. For me the biggest difficulty in my life was to do that—to lead several lives at once and to not give in and to not abandon any of them—to not give up children, to not give up the cinema, to not give up men if one likes men.”

In 1974, German television gave Varda carte blanche to make a new film, with a one-year deadline—but a year earlier she had given birth to her second child, and she knew from experience how difficult it was to care for a small child while on a film set. So she resolved to make her next film without leaving home. “I told myself that I was a good example of women’s creativity—always a bit stuck and suffocated by home and motherhood,” she said in 1975.

So I wondered what could come of these constraints. Could I manage to restart my creativity from within these limitations? . . . So I set out from this idea, from this fact that most women are stuck at home. And I attached myself to my hearth. I imagined a new umbilical cord. I had a special eighty-meter electric cable attached to the electric box in my house. I decided I would allow myself that much space to shoot [her next film]. I could go no further than the end of my cable. I would find everything I needed within that distance and never venture further.

The plan worked: Varda ended up filming the daily lives of the merchants in her neighborhood, for the documentary Daguerréotypes. This was fairly typical of her working process; she liked to work fast, “to film as soon as the idea comes to me,” she said, while she was still “in the throes of imagination.” (She wrote her 1965 film Le Bonheur in three days.) Nevertheless, Varda was dismissive of the idea of inspiration:

You know artists used to talk about inspiration and the muse. The muse! That’s amusing! But it’s not your muse, it’s your relationships with the creative forces that makes things appear when you need them. . . . So you have to work with free association and dreaminess, let yourself go with memories, chance encounters, objects. I try to achieve a balance between the rigorous discipline I’ve learned in my thirty years of making films and these many unforeseen moments and the vibrations of chance.

One of the advantages of getting older, Varda said in 1988, was that she felt a growing tranquility about her career. She no longer got tense about the work she had yet to do; she enjoyed, she said, “the privilege of having something in me that no one can touch, which no one can destroy.” And then, when the opportunity to make a new film came along, she would spring into action with tremendous energy. “I tend to wear out the people on my team with the extreme speed at which I do things and also by my demands on them,” she said. “I get up at five a.m. to write my dialogs. I get to the set an hour before anyone else to check things out. I may have last minute ideas and want to set them in motion right away. I make incredible demands without any doubts about whether they’ll work.”

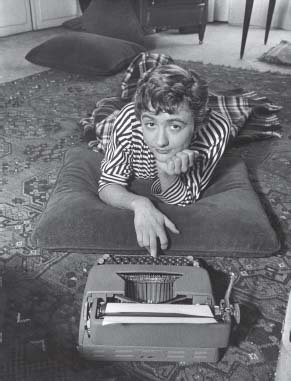

The French novelist, playwright, and screenwriter was best known for her first book, Bonjour Tristesse, published in 1954 when she was eighteen years old. Sagan wrote the book, she said, in “two or three months, working two or three hours a day,” without much forethought or advance planning. “I simply started it,” she said. “I had a strong desire to write and some free time.” She wasn’t sure she could write an entire book, but once she began the attempt she “wanted passionately to finish it.” Afterward, Sagan thought publication unlikely but dropped it off at a Paris publisher anyway; the publisher offered her a lucrative contract and brought out the book a few months later.

Françoise Sagan, Paris, 1955

Bonjour Tristesse was an immediate best seller and made its teenage author a celebrity, dubbed “an 18-year-old Colette” by Paris Match. The book’s profits allowed her to live an extended adolescent fantasy, spending freely, drinking immoderately, and eschewing bourgeois values and comforts. “I don’t like falling into habits, living in the same old setting, living through the same old things,” Sagan said in 1974, twenty years after her literary debut. “I’m always moving house—it’s quite manic. The material problems of day-to-day living bore me silly. As soon as someone asks me what we should have for dinner I become flustered and then sink into gloom.”

Needless to say, Sagan never followed any particular writing routine. “Sometimes I write in bursts of ten days or a fortnight at a time,” she said. “In between, I think about the story, day-dream and talk about it. I ask people for their opinions. Their opinions matter a lot.” She always started with a rough draft, which she wrote quickly, sometimes completing ten pages in an hour or two. “There’s never any plan because I like improvising,” she said. “I like to feel that I’m pulling the strings of the story and that I can pull them whichever way I like.” But after the draft was done she revised carefully, paying special attention to the rhythm and balance of her sentences: “There mustn’t be a syllable or a beat missing.” When the writing didn’t meet her standards, Sagan found the process “humiliating,” she said. “It’s rather like dying; you feel so ashamed of yourself, ashamed of what you’ve written. You feel pathetic. But when it’s going well, you feel like a well-oiled machine that’s working perfectly. It’s like watching someone run a hundred yards in ten seconds. It’s a miracle.”

Naylor wrote her debut novel, The Women of Brewster Place, while she was an undergraduate at Brooklyn College, and while also working as a switchboard operator at a hotel and going through a divorce. “I didn’t realize then that mine was an impossible schedule,” she recalled later. She wrote whenever she could fit it in, on her days off, between work and classes, and during night shifts at the hotel. “I was working alone because you know one operator can handle a hotel at night,” she said in a 1988 interview. “And after about 2:30 or 3:00, I would sit there and edit what I had written during the day. I had to do it like that.” Although this suggests formidable willpower, Naylor insisted that she was “not an overly disciplined person. It was something I wanted to do. It was something that was starting to flow out of me. It was helping me to achieve order because my personal life had been in total chaos.”

She finished the novel the same month she graduated from college, and initially she intended to go on to earn a doctorate and become a professor. But the immediate critical and commercial success of Brewster Place—which won the 1983 National Book Award for a first novel—changed her plans; Naylor quit graduate school after earning her master’s and set out to become a professional writer, supporting herself through fellowships, teaching jobs, and, eventually, a position on the executive board of the Book of the Month Club. Her working schedule varied, depending on the project at hand and her other commitments, but when she could she preferred to start in the early morning and work until noon or 1:00 p.m., then spend the afternoon on nonliterary chores. She was never picky about her writing conditions. “My needs are simple,” she said. “Bottom line: I need a warm and quiet place to work.”

She was similarly matter-of-fact about the writing process, describing herself as “a transcriber of stories” that arrived pretty much of their own accord. “The process starts with images that I am haunted by and I will not know why,” she said. “People will say, ‘How do you know that’s to be a story or a book?’ I say, ‘Because it won’t go away.’ You just feel a dis-ease until somehow you go into the whole, complicated, painful process of writing and find out what the image means. And often, when I’ve gotten into a work, I have been sorry to find out what the image meant. But the die is cast.”

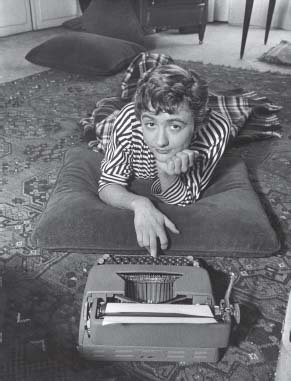

Neel was one of the great portrait artists of the twentieth century, although she didn’t begin to be recognized until she was in her sixties and had been working in near obscurity for decades. Despite poverty, critical and commercial neglect, and the responsibility of raising her two sons alone, Neel managed to paint pretty much every day, getting by on various forms of government assistance—initially drawing a salary as a Works Progress Administration artist, and then, when that program ended, collecting welfare. (According to her family, she was also a lifelong shoplifter.) When an interviewer asked how she painted with two young kids in the house, Neel said that, at first, she worked at night while they were sleeping; later, when they got older, she worked during the day while they were at school. She never seriously considered taking time off from her art. “If you decide you are going to have children and give up painting during the time you have them, you give it up forever,” she said. “Or if you don’t, you just become a dilettante. It must be a continuous thing. Oh, you may stop for a few months, but I don’t think you can decide to stop for years and do a different thing. You get divorced from your art.” In this and everything else, Neel refused to compromise; it was the artist’s prerogative to be selfish, she thought, and she would not feel guilty about it, especially when male artists were granted these privileges without question. She told students in a 1972 lecture, “I felt women represented a dreary way of life, always helping a man and never performing themselves, whereas I wanted to be an artist myself! I could certainly have accomplished more with a good wife. That is quite male chauvinist, but this was the world with which I was confronted.”

Alice Neel, New York, 1961

“You were encouraged to write by your family?” a reporter from the New York Post asked Jackson in September 1962. “They couldn’t stop me,” she replied. Jackson wrote six novels and dozens of short stories—including, most famously, “The Lottery,” her 1948 tale of ritual stoning in a sleepy New England village—while also managing a bustling family life, with four children, a menagerie of pets, and a husband who took the hands-off approach to parenting typical of midcentury American fathers. While he worked as a literary critic, a magazine editor, and a professor, Jackson ran the household and squeezed in her writing around childcare and housekeeping duties. She said in a 1949 interview, “50 per cent of my life is spent washing and dressing the children, cooking, washing dishes and clothes, and mending. After I get it all to bed, I turn around to my typewriter and try to—well, to create concrete things again.”

Though Jackson sometimes complained about the difficulty of reconciling the two roles, she also—as Ruth Franklin argues in her biography Shirley Jackson: A Rather Haunted Life—“seems to have derived imaginative energy from the constraints.” Franklin continues:

Writing in the interstices—the hours between morning kindergarten and lunch, while a baby napped, or after the children had gone to bed—demanded a discipline that suited her. She was constantly thinking of stories while cooking, cleaning, or doing just about anything else. “All the time that I am making beds and doing dishes and driving to town for dancing shoes, I am telling myself stories,” she said in one of her lectures. Even later, when the children were older and she had more time, Jackson would never be the kind of writer who sat at the typewriter all day. Her writing did not begin when she sat down at her desk, any more than it ended when she got up: “A writer is always writing, seeing everything through a thin mist of words, fitting swift little descriptions to everything he sees, always noticing.”

And, compared to housekeeping, writing was fun. “My husband fights writing,” Jackson said in 1949; “it is work for him, at least he calls it work. I find it relaxing. For one thing, it’s the only way I can get to sit down. There is delight in seeing a story grow; it’s so deeply satisfying—like having a winning streak in poker.”

The first African American woman to have a solo exhibition at the Whitney Museum of American Art, Thomas taught art to public-school students in Washington, D.C., for twenty-five years while pursuing her own practice on the side. She didn’t become a full-time artist until she retired from teaching in 1960, at age sixty-eight, and she didn’t receive widespread recognition for another decade. (The Whitney Museum exhibition opened in 1972, when Thomas was eighty.) Asked why she didn’t try to become a professional artist right after college, where she had studied painting and sculpture, Thomas said that it wasn’t that simple; she told a friend that “for educated young black people there were so many expectations then, so many pressures to conform.” But, she added, “I never lost this need to create something original, something all my own.”

Throughout her years of teaching, Thomas was always seeking out ways to continue developing as an artist. Starting in 1930, she spent three summers at Columbia University, in New York, earning a master’s in art education; while in the city, she began devotedly attending its museums and contemporary-art galleries. And in 1950, at age fifty-nine, Thomas enrolled at American University, to continue her studies in painting and art history. She never married or had children, believing it would have been too much of a distraction; she said, “a woman simply can’t do justice both to a family and to art. She has to choose which she wants.”

Alma Thomas, 1976

After she finally retired from teaching, Thomas threw herself into painting full-time, embracing watercolors as her primary medium. She worked in the kitchen or living room of her small house in Washington, propping canvases on her lap or balancing them on the sofa. She claimed to have no regrets about her late start. “I don’t know how it happened, but it seems to me that I’ve conducted my life so that every time I came to a crossroads I took the right turn,” she told a visiting critic in 1977.

I never married, for one thing. That was a place I know I made the right choice. The young men I knew cared nothing about art, nothing at all. And art was the only thing I enjoyed. So I have remained free. I paint when I feel like it. I didn’t have to come home. Or I could come home late and there was nobody to interfere with what I wanted, to stop and discuss what they wanted. It was what I wanted, and no argument. That is what allowed me to develop.

If Thomas did have one regret, it was that not long after becoming a full-time painter she developed chronic arthritis that made her increasingly frail. “Do you have any idea what it’s like to be caged in a seventy-eight-year-old body and to have the mind and energy of a twenty-five-year-old?” she asked. “If I could only turn the clock back about sixty years, I’d show them.”

Krasner was once asked to name the greatest sacrifice she had made for her art. “I sacrificed nothing,” she replied. Many observers had a hard time believing her. Krasner began studying painting in high school, became a full-time artist in her mid-twenties, and by the end of her life had received widespread recognition as a pioneer of Abstract Expressionism. But for fourteen years she was also married to Jackson Pollock, and his achievements as a painter—and his notorious self-destructiveness, which culminated in his death in a drunken car accident in 1956—always overshadowed Krasner’s own career. Nevertheless, she insisted that her and Pollock’s partnership was an equal one, and that he was always “very supportive” of her work. “Since Pollock was a turbulent man, life with him was never very calm,” Krasner said. “But the question—should I paint, shouldn’t I paint—never arose. I didn’t hide my paintings in a closet; they hung on the wall next to his.”

It was Krasner who pushed for their move out of New York City, where they had met and become a couple, hectoring Pollock’s gallerist and patron, Peggy Guggenheim, for a $2,000 loan to help them buy an old, unheated farmhouse in Springs, a fishing village on eastern Long Island. They moved in the fall of 1945, and Pollock converted a barn on the property into his studio; Krasner took a small upstairs bedroom in the farmhouse as hers. In Springs, Pollock would sleep until 11:00 a.m. or noon and then goof off until the late afternoon, when he would head into the barn to begin painting. Meanwhile, Krasner would get up at 9:00 or 10:00 a.m. and work upstairs. “He always slept very late,” Krasner recalled.

Morning was my best time for work, so I would be in my studio when I heard him stirring around. I would go back [downstairs], and while he had his breakfast I had my lunch. . . . We had an agreement that neither of us would go into the other’s studio without being asked. Occasionally, it was something like once a week, he would say, “I have something to show you.” . . . He would ask, “Does it work?” Or in looking at mine, he would comment, “It works” or “It doesn’t work.”

Life in the country was good for them, at least at first. They divided up the chores more or less evenly, with Krasner doing the cooking but Pollock in charge of baking (he made “marvelous bread and pies,” she said), and with the spouses sharing the gardening and lawn work. Without his New York pals to go out with, Pollock initially drank less, and it was during these years that he developed the drip-painting technique that characterized his mature style. Krasner had her own creative breakthrough; after years of feeling miserably stuck, working her canvases over and over until they became “pasty crusts of grey,” in the words of one critic, she arrived at her Little Image series—intimate canvases layered with abstract symbols, some achieved with her own version of drip painting—which became among her most successful paintings, although their importance was not recognized until the 1970s.

Eventually, as Pollock resumed drinking and his binges grew worse, Krasner moved from the upstairs bedroom to her own separate studio building, a former smokehouse on an adjoining acre of land that they were able to purchase. After Pollock’s death, Krasner divided her time between Long Island and Manhattan, where she took an apartment in a doorman building on the Upper East Side. She turned the master bedroom into her studio and slept in the smaller guest bedroom, which made it easy for her to get up in the night and paint during her periodic bouts of insomnia. In 1974, Krasner described her work schedule as “a very neurotic rhythm of painting. I have a high discipline of keeping my time open to work. If I’m in a real work cycle, I’ll pretty much isolate myself and paint straight through, avoiding social engagements.” The times in between these concentrated work spells were difficult; she was always eager to get back to painting, but she didn’t believe in forcing the process. “I believe in listening to cycles,” she said in 1977. “I listen by not forcing. If I am in a dead working period, I wait, though those periods are hard to deal with. For the future, I’ll see what happens. I’ll be content to get started again. If I feel that alive again. If I find myself working with the old intensity again.”

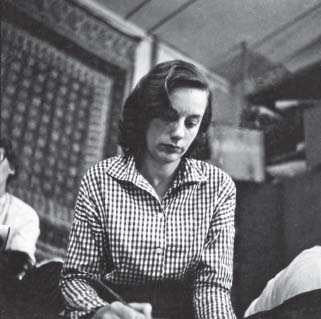

Hartigan was one of the foremost painters of the second-generation Abstract Expressionists, those mostly New York artists who followed in the footsteps of Willem de Kooning and Jackson Pollock to expand the bounds of visual abstraction. Hartigan’s journals from the early 1950s, published in 2009, vividly chart her creative process. In this July 1955 entry, Hartigan describes her lifestyle as a young painter on New York’s Lower East Side:

Now my days alone have a certain shape to them—I wake about nine, turn on the symphony and have juice, fruit and a pot of black coffee. Read a bit (still Gide’s Journal), talk on the phone . . . Then three or four, sometimes five hours on this canvas—it hasn’t begun to come yet, but I keep thinking of things to do.

Then a few domestic chores for myself, a cold shower, a cold hard boiled egg and one or two rums with Rose’s lime, more reading, some records. To-night I meet Frank [the poet Frank O’Hara] at the Cedar for dinner, then to the late showing of “East of Eden.” I feel sharp, my reading is concentrated and not “escape.” I have thoughts, ideas. And the news of Tom Hess’ coming article on the younger painters, profuse reproductions of “everyone,” but me, does not fill me with paranoia and depression, I am interested, but not upset.

Grace Hartigan, New York, 1950s

The article Hartigan mentions was one of the last times she would be left out of this kind of survey. But she was not always so sanguine about her career prospects, or so straightforwardly productive. Rather, Hartigan vacillated between periods of confident progress and painful inactivity. Months earlier, she had written:

I am in one of those terrible times when I feel “painted out.” I alternate between ennui and restlessness—an ennui that stupefies me, keeps me curled in my chair for hours and hours, reading anything—movie books, detective stories, “literature,” old journals. Or the restlessness that makes me walk the floor, staring out one window and then another, or sends me dashing into the street to stare into people’s faces or dash from one gallery to another, or pace frantically through museums looking for what, some clue, some hint, anything in life or art that will get me out of this pit.

Eventually, the working spirit would come back of its own accord, sometimes after a few days, sometimes not for weeks. “Art cannot be seized head on, it must be stalked, it is elusive,” Hartigan wrote in her journal. “And the only way it can be ever found is not knowing it except through occasional flashes of insight and revelation.” And this required constant vigilance and determination. As Hartigan wrote in another journal entry, “One must be fierce.”

Bambara began her career as a short-story writer, publishing two collections—Gorilla, My Love and The Sea Birds Are Still Alive—in the 1970s. She never followed a strict writing schedule, using spare bits of time while raising her daughter, teaching and lecturing at universities, and working as a civil-rights activist. “There’s no particular routine to my writing,” Bambara told an interviewer, “nor have any two stories come to me the same way.”

I’m usually working on five or six things at a time; that is, I scribble a lot in bits and pieces and generally pin them together with a working title. The actual sitdown work is still weird to me. I babble along, heading I think in one direction, only to discover myself tugged in another, or sometimes I’m absolutely snatched into an alley. I write in longhand or what kin and friends call deranged hieroglyphics. I begin on long, yellow paper with a juicy ballpoint if it’s one of those 6/8 bop pieces. For slow, steady, watch-the-voice-kid, don’t-let-the-mask-slip-type pieces, I prefer short, fat-lined white paper and an ink pen. I usually work it over and beat it up and sling it around the room a lot before I get to the typing stage. I hate to type—hate, hate—so things get cut mercilessly at that stage. I stick the thing in a drawer or pin it on a board for a while, maybe read it to someone or a group, get some feedback, mull it over, and put it aside. Then, when an editor calls me to say, “Got anything?” or I find the desk cluttered, or some reader sends a letter asking, “You still breathing?” or I need some dough, I’ll very studiously sit down, edit, type, and send the damn thing out before it drives me crazy.

But Bambara’s switch from short stories to the novel—she published her debut novel, The Salt Eaters, in 1980—also meant adjusting her approach to writing. She wrote in a 1979 essay:

I’d never fully appreciated before the concern that so many people express over women writers’ work habits—how do you juggle the demands of motherhood, etc.? Do you find that friends, especially intimates, resent your need for privacy, etc.? Is it possible to wrench yourself away from active involvement for the lonely business of writing? Writing had never been so central an activity in my life before. Besides, a short story is fairly portable. I could narrate the basic outline while driving to the farmer’s market, work out the dialogue while waiting for the airlines to answer the phone, draft a rough sketch of the central scene while overseeing my daughter’s carrot cake, write the first version in the middle of the night, edit while the laundry takes a spin, and make copies while running off some rally flyers. But the novel has taken me out of action for frequent and lengthy periods. Other than readings and an occasional lecture, I seem unfit for any other kind of work. I cannot knock out a terse and pithy office memo any more. And my relationships, I’m sure, have suffered because I am so distracted, preoccupied, and distant. The short story is a piece of work. The novel is a way of life.

“To choose the life of a writer,” Walker wrote in the early 1980s, “a black female must arm herself with a fool’s courage, foolhardiness, and serious purpose and dedication to the art of writing, strength of will and integrity, because the odds are always against her. The cards are stacked. Once the die is cast, however, there is no turning back.” Walker knew all about dedication, and long odds: She began her first novel, Jubilee, in the fall of 1934, when she was a nineteen-year-old senior at Northwestern University, and finished the first draft in April 1965, more than three decades after its inception. In the intervening years she earned a master’s degree, published a celebrated book of poetry—1942’s For My People—embarked on a university teaching career, got married, and raised four children. But the novel was always in the back of her mind. Whenever she could, Walker tried to find time to continue the research and writing, but she often failed to fit it in; for a seven-year stretch, between 1955 and 1962, she didn’t write a single word. “People ask me how I find time to write with a family and a teaching job,” she wrote years later.

I don’t. That is one reason I was so long with Jubilee. A writer needs time to write a certain number of hours every day. This is particularly true with prose fiction and absolutely necessary with the novel. Writing poetry may be different, but the novel demands long hours every day at a steady pace until the thing is done. It is humanly impossible for a woman who is a wife and mother to work on a regular teaching job and write. Weekends and nights and vacations are all right for reading but not enough for writing.

Indeed, Walker was able to finish the book only by going back to graduate school at the University of Iowa—leaving her husband and children behind, temporarily—and working out an arrangement whereby her novel would serve as her dissertation. Even so, she had to spend two years attending to other graduate-school requirements before she could give the novel her full attention. In the fall of 1964 she was finally able to get back to Jubilee, and then she worked fast, writing longer and longer hours as she neared the end. In the following spring, Walker “worked from seven in the morning until eleven and stopped for lunch,” she later recalled. Then she “went back to the typewriter and worked in the afternoon until supper or tea at four and then after supper until eleven o’clock. I pushed myself beyond all physical endurance, and in two months, I was happy to lose twenty pounds.”

She was happier to have finished the book—although she later admitted that Jubilee’s long gestation process was in many ways essential to its success. Asked what it was like to live with the book for so long, Walker said:

You just become part of it, and it becomes part of you. Working, raising a family, all of that becomes part of it. Even though I was preoccupied with everyday things, I used to think about what I wanted to do with Jubilee. Part of the problem with the book was the terrible feeling that I wasn’t going to be able to get it finished. . . . And even if I had the time to work at it, I wasn’t sure I would be able to do it the way I wanted. Living with the book over a long period of time was agonizing. Despite all of that, Jubilee is the product of a mature person. When I started out with the book, I didn’t know half of what I now know about life. That I learned during those thirty years. . . . There’s a difference between writing about something and living through it. I did both.