“It is highly probable, nay almost certain, they mean to make a push; their object is a secret, only known to them, tho’ I have my conjectures.”1

— George Washington, February 23, 1777

The maneuvers that initiated the Philadelphia campaign and ultimately led the armies to the banks of the Brandywine River did not begin until June of 1777, six months after Trenton and Princeton. Because there was neither a single major battle fought nor much maneuvering during those six months, this time period is often overlooked.

In fact, both Washington and Howe were active during this relative lull, but in very different ways. Washington spent these months rebuilding an army that was on the brink of collapse in December 1776. Even though it was an army-under-construction, Washington did not let it sit idle. Instead, he harassed and pestered British outposts in northern New Jersey in a series of skirmishes and raids. These activities not only kept the men alert and active, but also sharpened their skills in the field against a real enemy. Howe, meanwhile, spent this time sending dispatches to London that altered his plans for the spring, while those in authority in London continued to conjure up a strategy sure to win the war in 1777, notwithstanding Howe’s letters.

Washington’s main army remained in the hills around Morristown, New Jersey, about 25 miles west of New York City throughout this period. A series of ridges known as the Watchung Mountains shields Morristown to the east. The formation rises from 450 to 879 feet above sea level, with cliff-like approaches in some places. Washington used this high ground to observe the countryside all the way to Sandy Hook, New Jersey, and keep an eye on the roads between New York City and Philadelphia. Morristown contained about 70 houses clustered around an eight-acre village green and was home to around 350 people. Several thousand more lived in the villages of Madison, Westfield, Chatham, Whippany, Boonton, Rockaway, Bound Brook, Parsippany, and Basking Ridge around Morristown. By the end of the winter, Continental troops were camping in all of those towns.

Morristown provided a number of advantages to the Continental Army. As noted, the town sat in the midst of hilly terrain that could be easily defended, even by an American army that was regrouping following the disasters of 1776. The town was home to numerous patriots and several of New Jersey’s leaders. Just a few months previously, Charles Lee’s division had camped there and found the population to be friendly. Scattered around the village were a number of ironworks which produced ammunition and perhaps cannon for the army. The town also had an organized body of militia, one of the few in the state. The town appeared very religious, which Washington deemed important. Morristown was also roughly the midway point between New York and Philadelphia, and close to the main road connecting the two ports. Finally, the town was within supporting distance of Washington’s other bodies of troops in New York, Connecticut, and Rhode Island. In an emergency, his Continental Army could quickly shift to any of those areas.2

New York City hosted the general headquarters for the British, who also maintained a large field force at New Brunswick, New Jersey, a provincial trading town on the Raritan River. There were additional British outposts between the Raritan and Perth Amboy, the capital of East Jersey.3

New Brunswick was composed of about 400 houses, many of which had been partly deserted or destroyed. The commercial village was a shadow of its former self. Before war came to the region the previous summer, New Brunswick had been a thriving port town with a mix of Dutch and English colonial architecture. The town served as a rendezvous point in 1776 when thousands of American troops moved north from the more southern colonies to defend New York.4 When the Americans suffered repeated defeats attempting to hold New York and retreated across northern New Jersey, the town was evacuated and many of the residents fled. The British promptly occupied the town, which both sides pillaged.

After the British were defeated at Trenton and Princeton, the headquarters for New Jersey was established in New Brunswick. Fortifications were constructed, and several elite British and Hessian units garrisoned the town. These troops included British and Hessian grenadiers and Hessian jaegers, with Maj. Gen. Charles Cornwallis in command.5

While the British forces dug in and patrolled along the Raritan River, George Washington, just to the west in the mountains surrounding Morristown, evaluated and reorganized what was left of his Continental Army. What he discovered could only have been dismaying. Still with him were some militia from New Jersey and Pennsylvania, and small numbers of loyal Continental Regulars who had remained even after their enlistments ran out on December 31. Congress had approved the creation of a Continental Army in 1776 for just one year’s duration. Those who had enlisted at that time fulfilled their commitment on the last day of the year; many left the army the next day. Thousands more had been killed, wounded, or captured. The force at Morristown was about 90 percent (roughly 20,000 men) smaller than the army Washington had led around New York City just a few months earlier. Congress and Washington faced a Herculean task in rebuilding the colonial force that spring of 1777.

To buy time to rebuild the army, Washington authorized a series of ambushes and raids on the British outposts, but no large-scale engagements. Many of the opposing troops caught in these ambushes and raids tended to be Hessian. While Howe had issued orders forbidding the plundering of the countryside, the German troops contracted to assist the British war effort were not subject to British military discipline. There was little Howe could do to stop them from raiding the local inhabitants. Unfortunately for Howe, his British regulars saw the Hessian troops pillaging and decided they too should be allowed to reap the bounty around them. Discipline within Howe’s army deteriorated as both Hessian and British soldiers roamed the area indiscriminately. While they were out seeking plunder, they were vulnerable to Washington’s raids and ambushes.

Unfortunately for the fledgling American army, an outbreak of smallpox erupted as soon as it arrived at Morristown, sickening soldiers and civilians alike. Washington quickly decided to inoculate his entire army rather than run the risk of losing a number of the few troops he still had with him:

Finding the small pox to be spreading much and fearing that no precaution can prevent it from running thro’ the whole of our Army, I have determined that the Troops shall be inoculated. This Expedient may be attended with some inconveniences and some disadvantages, but yet I trust, in its consequences will have the most happy effects. Necessity not only authorizes but seems to require the measure, for should the disorder infect the Army, in the natural way, and rage with its usual Virulence, we should have more to dread from it, than from the Sword of the Enemy.6

While smallpox itself and the inoculations against it disabled many American soldiers, not all were knocked out of circulation. Notwithstanding the many popular histories of the American Revolution, British and Hessian troops were not the only soldiers stealing, plundering, and destroying private property in New Jersey that spring—American troops were just as guilty. Most of the thieving colonials were members of the New Jersey militia. Militiamen were notoriously undisciplined, and Washington had little control over them. As far as these Jerseymen were concerned, it was their right to plunder from New Jersey Loyalists. Many of their neighbors had remained loyal to the Crown or had joined a British regular regiment or one of the many provincial regiments the British formed with American colonists. Much like Howe, Washington could do little to curb the plundering occurring along the periphery of his army.

Within weeks after the turn of the year, inflation combined with a lack of commerce and the difficulty in obtaining many goods further weakened Washington’s army. Despair and apathy set in. Support from both locals and Congress plummeted, while desertion skyrocketed.7 At the end of January, Washington informed the President of the Congress, John Hancock, that the army was “shamefully reduced by desertion and … [if] the people in the Country can be forced to give Information, when Deserters return to their old Neighbourhoods, we shall be obliged to detach one half of the Army to bring back the other.” Washington also wanted the assemblies in the states providing militiamen to pass laws providing a severe penalty for hiding and protecting deserters.8

Despite these debilitating distractions, Washington managed some small-scale accomplishments. Captain Levin Friedrich Ernst von Muenchhausen of the Hessian Leib Regiment had been appointed Howe’s aide-de-camp in November 1776, and served with him until Howe returned to England in May 1778.9 According to von Muenchhausen, “Up to the 21st of January, nothing noteworthy happened except that our troops stationed in Jersey have been continuously harassed by Washington. Having a sizable army, he has forced us to abandon Elizabethtown, inflicting the loss of 80 Waldeckers, and now we are occupying only Brunswick and Amboy.” The abandonment of Elizabethtown came about when the British sent out a reconnaissance party in the direction of Springfield composed of 13 members of the 17th Light Dragoons and a body of Waldeckers. When British intelligence overestimated the number of troops Washington had at his disposal, they decided to abandon Elizabethtown.10

The conflict had devolved into what we today call guerilla warfare— ambushes and sniping punctuated by occasional atrocities. In the eighteenth century, this form of partisan warfare was known by the French term la petite guerre, or “small war.” Late in February, Washington described what was occurring to his northern front commander, Maj. Gen. Philip Schuyler. “There have been and almost daily are, some small Skirmishes,” he explained, “but without much loss on either side, they have generally been favourable to us.”11

Washington did not expect this form of warfare to last. After noting the buildup of British forces at New Brunswick, he told Schuyler, “I do not apprehend, however, that this Petit Guerre will be continued long, I think matters will be transacted upon a larger Scale. The Troops at Brunswick have been considerably reinforced of late, and Genl. Howe and Piercy are said to have come over, their number there and the dependent posts, must be from 10 to 12,000; from these Circumstances,” he concluded, “It is highly probable, nay almost certain, they mean to make a push; their object is a secret, only known to them, tho’ I have my conjectures.”12 Luckily for Washington, whose army was in no state to wage a pitched battle, he was wrong: the bushwhacking continued for months, which in turn gave him time to rebuild the Continental Army.

Captain Sir James Murray of the British 57th Regiment of Foot also described the mode of fighting in a letter to his sister in Scotland. “We have a pretty amusement known by the name of foraging or fighting for our daily bread. As the rascals are skulking about the whole country, it is impossible to move with any degree of safety without a pretty large escort,” he explained, “and even then you are exposed to a dirty kind of tiraillerie [random gunfire], which is more noisy indeed than dangerous.” Notwithstanding Murray’s light treatment of the matter, the stress and psychological toll of the constant harassment during these months eventually led to some of the savageness during the Philadelphia campaign—particularly at Paoli.13

Among the many skirmishes, one on February 23 escalated into a slightly larger engagement. A 2,000-man British foraging party departed Perth Amboy and headed in the direction of Woodbridge, New Jersey. As the men spread out to begin foraging, Continental troops under Brig. Gen. William Maxwell assaulted the grenadier company of the 42nd Royal Highlanders. Although the British fought well, they were heavily outnumbered and forced to withdraw, losing more than 70 casualties in the affair while the Americans lost only a few men. After visiting some of his wounded, Capt.-Lt. John Peebles of the 42nd Highlanders jotted down his thoughts on the previous day’s action: “Several of them [were] in a very dangerous way poor fellows, what pity it is to throw away such men as these on such shabby ill managed occasions.” A lack of support for the exposed Highlanders had doomed the operation.14

By March 1777, Washington was recruiting new soldiers, reorganizing his fragmented army, and determining his strategy for the year. On the 12th of the month, Washington sent a letter to Maj. Gen. Philip Schuyler, quoted here at some length for its exposition of Washington’s thinking:

It is of the greatest importance to the safety of a Country involved in a defensive War, to endeavour to draw their Troops together at some post at the opening of a Campaign, so central to the theatre of War that they may be sent to the support of any part of the Country, the Enemy may direct their motions against. It is a military observation, strongly supported by experience, that a superior Army may fall a sacrifice to an inferior, by an injudicious division. It is impossible, without knowing the Enemy’s intentions, to guard against every sudden incursion, or give protection to all the Inhabitants; some principle object shou’d be had in view, in taking post to cover the most important part of the Country, instead of dividing our force, to give shelter to the whole, to attempt which, cannot fail to give the Enemy an Opportunity of beating us in Detachments, as we are under the necessity of guessing at the Enemy’s intentions, and further operations; the great object of attention ought to be, where the most proper place is, to draw our force together, from the Eastward and Westward, to cover the Country, prevent the Enemy’s penetration and annoy them in turn, shou’d our strength be equal to the attempt. There is not a State upon the Continent, but thinks itself in danger, and scarcely an Officer at any one post, but conceives a reinforcement necessary; to comply with the demands of the whole, is utterly impossible, and if attempted, would prove our inevitable ruin.15

Just two days later, Washington expressed his anxiety to Congress. Although the government was rapidly recruiting new soldiers to rebuild the army, they were not arriving fast enough for Washington. “I feel the most painful anxiety when I reflect on our Situation and that of the Enemy,” he confessed. “Unless the Levies arrive soon, we must, before it be long, experience some interesting and melancholy event. I believe the Enemy have fixed their object, and the execution will surely be attempted, as soon as the roads are passable. The unprepared state in which we are,” he concluded, “favors all their designs, and it is much to be wished they may not succeed to their warmest expectations.”16

While troops from both sides skirmished in the countryside and Washington developed a strategy for the upcoming campaign, anyone who cared to notice might have paid attention to the Delaware River area in March, where a man named James Molesworth had just been apprehended. Molesworth, a Pennsylvania loyalist, had been introduced to Admiral Lord Richard Howe by Joseph Galloway, a man whose name will forever be connected with the fighting at Brandywine. The admiral commissioned Molesworth to hunt down Delaware River pilots familiar with the passage through the obstructions Americans had sunk in the channel. Molesworth managed to bribe a couple of pilots, but the three of them were captured before they could return to New York. Several patriot pilots had notified authorities about Molesworth’s intentions. Molesworth confessed and was executed in late March. Elizabeth Drinker, a Philadelphia Quaker, noted the event in her diary: “A Young Man of the Name Molsworth was hang’d on the Commons by order of our present ruling Gentr’y.”17

Operations escalated in other ways as well. On April 12, Lord Cornwallis decided to ramp up the level of combat. A Continental outpost at Bound Brook, New Jersey, had been harassing British outposts for weeks and the British general had had enough. The Americans were under the command of Benjamin Lincoln, a Massachusetts native born in 1733 who had been elevated just two months earlier to the rank of major general. The next day, on April 13, Cornwallis led 4,000 British and Hessian troops along both sides of the Raritan River in an attempt to neutralize Lincoln’s position. Although most of the Americans escaped, the British captured about 70 men and three artillery pieces. The British victory proved short-lived: when Cornwallis returned to New Brunswick that afternoon, American elements reoccupied Bound Brook. Historian Thomas McGuire succinctly summarized the day’s events: “For all the fuss and bother, planning, marching, skirmishing, and recriminating, Cornwallis’s goal was only partially realized and of short duration.”18

The Bound Brook operation bothered Washington, and he made a prediction the next day. “If I am to judge from the present appearance of things the Campaign will be opened by General Howe before we shall be in any condition to oppose him.” Washington was worried that the strong probe meant that Howe was close to beginning his campaign while the American army was still heavily outnumbered in men and weapons, was not as well-trained, and did not enjoy the same logistical support. Unbeknownst to Washington, however, British intelligence continued to overestimate the size of his army.19

Despite Washington’s fears, the lethargic Howe was not yet ready to move. It would be several more weeks before he believed he was prepared to begin his important 1777 campaign. At the end of April, American division commander Nathanael Greene wrote his wife the latest news. “We learn the Enemy are to take the field the first of June,” explained Greene. “Their delay is un[ac]countable already. What has kept them in their Quarters we cant immagin.”20

One likely factor was the return on May 23 of a significant portion of the British garrison in Rhode Island to New York. After being informed that he could expect few reinforcements, Howe had abandoned all thoughts of his earlier plan of striking into Massachusetts from Rhode Island. He therefore brought back to his main army the men initially intended for that foray, which he intended to use to either increase the New York garrison or accompany him to Philadelphia.

Regardless of what else was or was not happening, skirmishing and partisan warfare continued along the Raritan River in New Jersey. On May 25—a blazing-hot day, according to Capt. von Muenchhausen—jaeger Capt. Johann Ewald found himself involved in a skirmish near Bound Brook. When the British received reports that the Americans had abandoned Bound Brook, they sent out a column on May 26 to secure the position. Major General James Grant, with the 1st Battalion of British Light Infantry along with a detachment of the 16th Light Dragoons, was tasked with the mission. The report of abandonment was untrue, and a lively skirmish took place. The British Brigade of Guards was sent out to support the operation when the firing broke out. Ensign Thomas Glyn, who marched with the Guards and was soon to return home with other Guards officers, recalled the scene: “The Enemy advanced with two pieces of Cannon & began to cannonade us, when we were ordered to lay down & being covered by the ground no loss ensued except Major General Grant having his Horse shot dead under him.” Many were amused by the loss of Grant’s horse, for he was not the most popular general officer in the British army. Indeed, several subordinates would not have been saddened to see the pompous Grant exit the army by any means. Lieutenant William Hale of the 45th Regiment of Foot, for example, wished “it had been the General instead of the horse, no man can be more detested.”21

American Brig. Gen. Anthony Wayne, no slouch to pomposity himself, boasted about the action at Bound Brook to Doctor Benjamin Rush: “We Offered Gen’l Grant Battle six times the Other day he as often formed but always on our Approach his people broke and Ran after firing a few Volleys which we never Returned, being Determined to let them feel the force of our fire and to give them the Bayonet under Cover of the Smoke.” Wayne went on to say that Grant, “who was to March through America at the head of 5000 men had his Coat much Dirtied, his Horses head taken off, and himself badly Bruis’d for having the presumption at the head of 700 British Troops to face 500 Penns’as.”22

The operation was a clear example of how poorly the British intelligence network performed that spring. The British consistently overestimated the strength of Washington’s army, which was in a constant state of flux as the rebuilding continued. “The fact that a sizeable enemy corps can march away and be gone for two hours before we learn of it, shows that we are in a bad way in not having good spies among them,” bemoaned von Muenchhausen.23

By May 28, Washington had shifted the majority of his army from its winter camp at Morristown to a forward position at Middlebrook. Washington, who always had more issues to manage than the time to do so, acquired about this time yet another headache in the form of a French officer. Sometime that May, Philippe Charles Trouson du Coudray arrived at Morristown with a document in his pocket authorizing him to assume command of all of the Continental Army artillery. The authorization to do so was signed by Silas Deane, one of the American commissioners sent by the Continental Congress to Paris. The problem for Washington, however, was that the position was held by the capable Henry Knox, a Boston native and former bookstore owner. The news infuriated American officers. With the Marquis de Lafayette about to join the army, many high-ranking officers were less than thrilled with the prospect of being outranked by young French officers. Nathanael Greene and John Sullivan submitted their resignations—operative if du Coudray’s contract was honored. “A report is circulating here at Camp that Monsieur de Coudray a French Gentleman is appointed a Major General in the service of the United States, his rank to commence from the first of last August,” was how Greene’s letter of July 1 opened to John Hancock, the president of Continental Congress. “If the report be true it will lay me under the necessity of resigning my Commission as his appointment supercedes me in command.” Washington was wise enough to know that losing Knox, Greene, and Sullivan would be a blow the army could ill-afford, while refusing to honor the agreement threatened to alienate the French. The army commander wisely defused the situation by giving du Coudray a staff assignment as Inspector General of Ordnances and Military Manufactories. The Frenchman would later play a major role in the defense of the Delaware River. The artillery command remained with Henry Knox, and Greene and Sullivan remained with their infantry commands.24

While Washington was shifting his army to Middlebrook, a contingent of reinforcements for Howe’s army arrived from Europe. A company of German riflemen from the principality of Anspach-Brandenburg was among them. Meant to be mounted, the men arrived heavily clothed and sporting knee-high boots. The horses and saddle gear these jaegers required, however, did not arrive with them. Throughout the upcoming campaign they would fight on foot while wearing the awkward uniforms of mounted troops. Along with the jaegers, a new contingent of officers from the three regiments of foot guards also arrived. Some of the officers who had come to America the previous year with the two battalions of Guards were now rotating home.25

The age of unpaved roads and horse-drawn transportation usually required good dry weather for active campaigning. May, however, slipped past without major British activity, and by the time June arrived in northern New Jersey, Howe had yet to make any positive movement. An expeditious campaign to capture Philadelphia would more likely than not have had a significant impact on Burgoyne’s operation from Canada into upstate New York, while a delay served the opposite effect. Nicholas Cresswell, an Englishman who had been traveling through the American colonies since 1774, passed through Virginia and Pennsylvania before making his way to New York. After having been in the city nearly three weeks, he confessed, “I am as ignorant of the Motions or designs of our Army as if I had been in Virginia.” The soldiers, thought Cresswell, “seem very healthy and long to be in action.” Howe, he continued, was either “inactive, has no orders to act, or thinks that he has not force sufficient to oppose the Rebels, but which of these or whether any of them is the true reason I will not pretend to say.” In fact, Cresswell held strong opinions as to why Howe remained inactive, one of which was the time he spent with his mistress, Mrs. Elizabeth Loring. The delay could only hurt the British cause, thought Cresswell: “But this I am very certain of, if General Howe does nothing, the Rebels will avail themselves of his inactivity by collecting a very numerous Army to oppose him, whenever he shall think it proper to leave Mrs. Lorain [Loring] and face them.” Howe, of course, did have orders to begin the campaign. He was supposed to capture Philadelphia and return to the Hudson River area in time to assist Burgoyne coming down from Canada. Cresswell, however, was correct about one thing: Washington was using the extra time very judiciously by rebuilding his Continental Army.26

On June 4—King George III’s birthday—General Howe hosted a large reception and the forts and ships in the harbor celebrated with each firing 21 gun salutes. Wrote one eyewitness, “You can imagine what thunderous noise it was, there being over 400 ships at anchor here. In the evening most of the houses were illuminated.”

When the pomp and ceremony and favors of the flesh would end, and the campaign begin, remained anyone’s guess.27

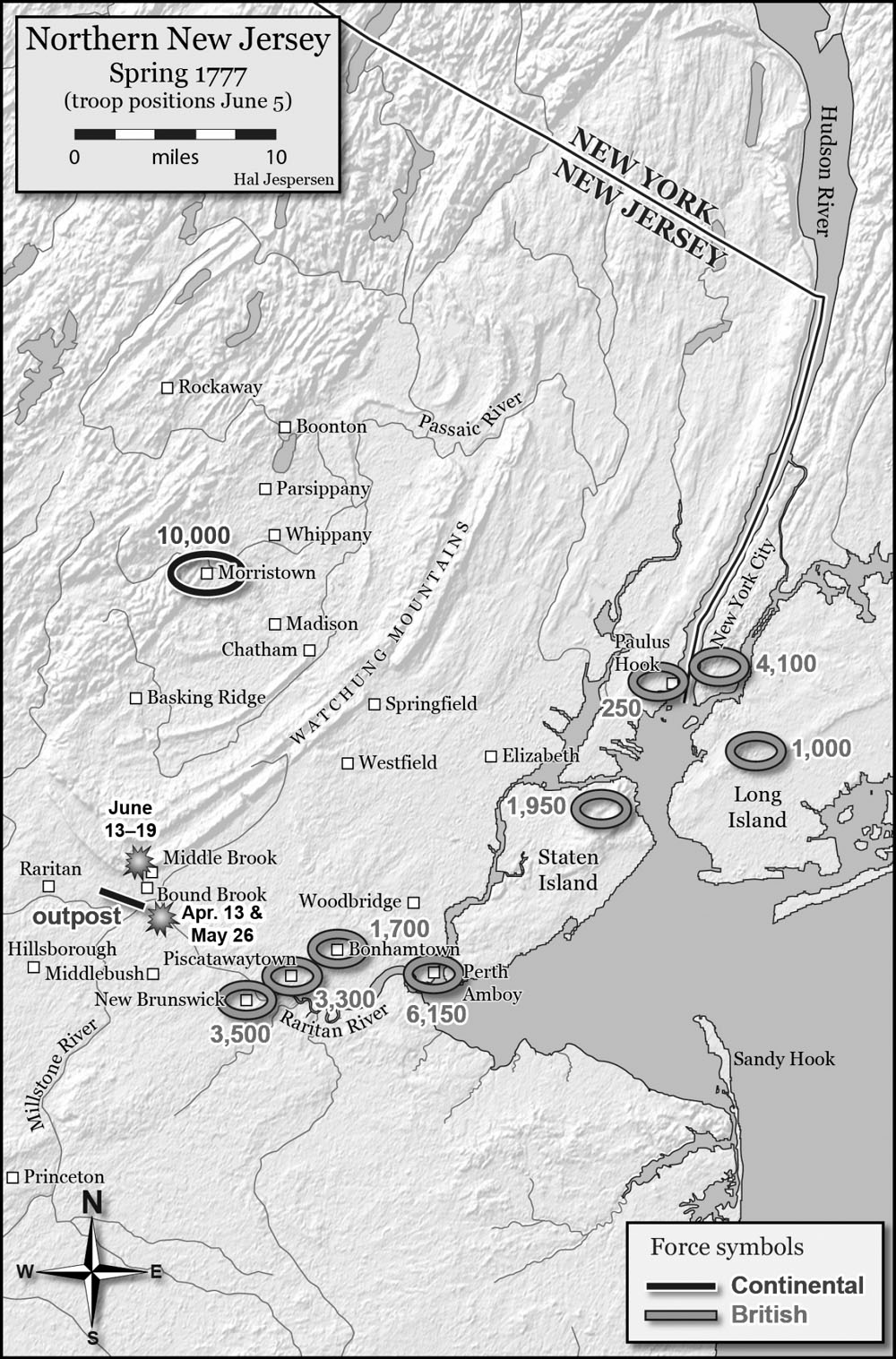

Just before major campaigning began, Hessian Captain von Muenchhausen prepared a helpful breakdown of the British army in and around New York:

In Rhode Island, under the recently exchanged Maj. Gen. Richard Prescott, were four Hessian regiments and three British regiments, totaling 2,750 men.

In New York City proper, under Hessian Gen. Wilhelm von Knyphausen, were five Hessian regiments, two British regiments, and three battalions of Provincials, totaling 4,100 men.

The 250 men of the 57th Regiment of Foot, under Lt. Col. John Campbell, were at Paulus Hook in New Jersey.

There were 1,000 provincials on Long Island.

In Amboy, New Jersey, under Gen. John Vaughn, were 13 British regiments, four Hessian regiments, the 17th Light Dragoons, and 400 provincials, for a total of 6,150 men.

Colonel James Webster at Bonhamtown, New Jersey, commanded three English regiments and the 71st Highlanders, a total of 1,700 men.

In and around Piscataway, New Jersey, Brig. Gen. Alexander Leslie commanded the Hessian jaegers, the 42nd Highlanders, four British regiments, the Brigade of Guards, and some provincials, totaling 3,300 men.

Lord Charles Cornwallis at New Brunswick, New Jersey, oversaw two battalions of British grenadiers, two battalions of British light infantry, the 16th Light Dragoons, and four Hessian grenadier battalions, a total of 3,500 men.

Lastly, on Staten Island there were three British regiments and the Anspachers, totaling 1,950 men.

As set forth above in von Muenchhausen’s accounting, the grand total available to General Howe was about 24,700 men.28

The question now confronting Howe was how best to get all these forces moving in a coordinated endeavor. He decided to begin with an expedition to Middlebush. This move constituted Howe’s initial attempt to use an overland march directly toward Philadelphia in an effort to maneuver Washington out of the mountains. If he could draw the colonials into a battle on the plains of northern New Jersey and defeat them there, the remainder of the march to Philadelphia would be relatively simple. A quick victory and expeditious march would also bode well for Burgoyne’s column from Canada, and prevent Washington from sending troops north.

Even though Howe had finally begun moving early that June, there was dissatisfaction within the ranks of his officer corps over the delay in doing so. According to Howe, he was forced to wait for the arrival of camp equipment and for grass to grow to feed his horses. At the beginning of 1777, Howe was indeed significantly hampered by a lack of provisions. The British government refused to supply him to any great extent with hay and oats, and thus required he obtain them in America. That logistical decision forced Howe to wait until green forage was available. Still, once the grass was high enough to eat he continued to drag his heels for weeks on end. Had he found a way to begin his campaign earlier that year, he might have had time to crush Washington’s army prior to the onset of winter, and then possibly have enough time to aid Burgoyne. Finally, on the night of June 13, Howe marched the bulk of his army in two divisions from New Brunswick to Middlebrook, New Jersey, and went into camp. With some 17,000 men involved in the move, it was the largest British operation since the capture of Fort Lee, New Jersey, the previous November.29

Howe’s intentions were unknown even to his own commanders. During the previous six months, boats that could be carried on wagons had been prepared in New York, leading many in the army to believe Howe intended to cross the Delaware River. “All the Long-Bottomed Boats were put into Waggons, and everything got in readiness,” wrote one member of Howe’s command. Others were less sure of what this meant and speculated the entire effort was nothing more than a diversion.30

Captain Archibald Robertson of the Royal Engineers, who served on Howe’s staff during the campaign, noted that the army’s destination was about five miles from New Brunswick and three miles from Hillsborough. According to Robertson, Washington’s army was strongly encamped about four miles north of Bound Brook in the mountains. Many assumed Washington would fall back when Howe was seen to be on the move. Unfortunately for the weary British troops, he did not. “I believe it was generally imagined upon our Armys making the Aforesaid Move, He [Washington] would have quitted his stronghold and retreated towards the Delaware,” the captain wrote in his journal. “However it proved otherwise, He stood Firm. No Certain Intelligence brought in of the Situation.”31

Another of Howe’s aides, von Muenchhausen, believed Howe had “planned a forced march at dawn in order to cut off and to throw back General Sullivan, who is at Princeton with 2000 men.” The Hessian’s conclusion was easy to reach, for all the tents and heavy baggage had been left behind and the men ordered to carry provisions for three days—certain signs of a campaign march.32 In addition, such a move was good strategy, for a sweep on Princeton could isolate and destroy Sullivan’s Continental division. To the Hessian aide, the move to Middlebush signaled the beginning of Howe’s long-awaited campaign. But Robertson, von Muenchausen, and many other British and Hessian officers would soon be disappointed.

* * *

Washington observed Howe’s movement from his mountain stronghold. Among the many new units raised during the restructuring of the army was a regiment of riflemen under Col. Daniel Morgan of Virginia. Born in 1736, Morgan left home as a teenager to live in the Shenandoah Valley and later served on the American frontier in the French and Indian War and Lord Dunmore War of 1754-1763 and 1774, respectively. When the Revolution erupted in 1775, Morgan took command of two Virginia rifle companies as a captain and marched to Boston. He played a critical role in the invasion of Canada later that year, but was captured at Quebec. After his exchange, he was promoted to colonel of the 11th Virginia Regiment. Morgan was a man Washington could depend upon, and he was about to call for his services in the face of Howe’s advance.

All the experienced riflemen throughout the army were detached from their parent regiments for service under Morgan. This reorganization grouped together about 500 frontiersmen, primarily from the mountains of Pennsylvania, Virginia, and Maryland, all armed with Pennsylvania long rifles. Washington issued Morgan orders to use his men as light infantry. “In case of any Movement of the Enemy you are Instantly to fall upon their Flanks and gall them as much as possible,” instructed Washington, “taking especial care not to be surrounded, or have your retreat to the Army cut off.”

Pennsylvania Rifles were accurate up to about 300 yards, but they were slower and harder to load. The standard smoothbore firearms carried by the two armies could be loaded two and even three times a minute under combat conditions, but a man carrying the Pennsylvania Rifle was lucky to get off one shot every minute under the same circumstances. The other deficiency with the weapon was that it was not constructed to hold a bayonet. Since the primary tactic of the British army was to close with the enemy and use the bayonet freely, riflemen facing such an assault were at a severe disadvantage.

Washington thus believed surprise was the best tactic for Morgan’s men. “It occurs to me that if you were to dress a Company or two of true Woods Men in the right Indian Style and let them make the Attack accompanied with screaming and yelling as the Indians do, it would have very good consequences especially if as little as possible was said, or known of the matter beforehand.”33 Morgan would be lining the roads to greet Howe’s advance.

The day after reaching Middle Brook, however, the unexpected took place. To the disbelief of officers on both sides, the British Army halted and established a camp. Light skirmishing broke out between the opposing sides near Hillsborough along the Millstone River. On June 15 Howe’s chief engineer, Capt. John Montresor, oversaw the construction of three earthen redoubts. The halt, coupled with the erection of defensive fortifications, made it clear that Howe—at least for the moment—did not intend to go any farther.34 The stop confused and maddened many of Howe’s officers and men. Captain von Muenchhausen jotted down in his diary that many blamed “General Howe for not having followed Washington immediately.” Howe’s aide, however, went on to defend the decision. “Nobody in the world could be more careful than he is. This is absolutely necessary in this cursed hilly country.”

American artillery chief Henry Knox thought the short movement and complete halt utterly perplexing. “It was unaccountable that people who the day before gave out in very gasconading terms that they would be in Philadelphia in six days should stop short when they had gone only nine miles,” wrote Knox in a letter. “What his next manoeuvres may be I can’t say, but we suppose the North River…. The motive for belief that the North River will be the scene of his operations is that intelligence is received that Mr. Burgoyne is about crossing the lakes to [Fort] Ticonderoga, and General Howe must make an attempt to push for a junction.”35

After several days of standstill, Howe’s intention became clear: Draw the Continental Army down from the mountains onto the open plain. If Howe’s purpose was to entice his enemy to attack him, he was sorely disappointed. Washington had no intention of coming down out of the mountains to play on Howe’s terms. “Washington is a devil of a fellow, he is back again, right in his old position, in the high fortified hills,” wrote one of Howe’s aides. “By retreating he supposedly intended to lure us into the hills and beat us there.” British Maj. Charles Stuart was not surprised by Howe’s attempt, but he did not believe it would work. Having recently lost his command of a grenadier battalion and been denied permission to return to England, Stuart was without a command that summer, and so accompanied Howe’s army from New Brunswick.36

As far as Stuart was concerned, the “idea of offering these people battle is ridiculous; they have too much caution to risk everything on one action, or rather too much sense to engage an army double their numbers, superior in discipline, and who never make a show of fighting but upon the most advantageous ground. If we wish to conquer them,” he concluded, “we must attack them.” Stuart knew that the British could not be afraid to draw Washington into a pitched battle or even outright assault his lines. “If we wish to conquer them we must attack him, or if his posts are too strong, by a ruse de guerre place ourselves in that situation that he may expect to attack us to advantage.”37

Civilians were baffled as well. A loyalist back in New York was simply disgusted by Howe’s lethargy. “Hints from head-quarters, that his Excellency, ever attentive to the sparing of his Gallant Troops, could not bear the idea of risking two or three thousand brave men to be sacrificed by ‘base scum, and dunghill villains’ …. Rebellion, which a twelvemonth ago was really a contemptible Pigmy, is now in appearance become a Giant.”

It was true that British field commanders, including Howe, were reluctant to unnecessarily bloody their regiments, especially in frontal assaults, because replacing veteran soldiers was a long and tedious process. But Howe had also become far too comfortable in New York. “All this time General Howe was at New York in the lap of Ease,” wrote one eyewitness, “or rather, amusing himself in the lap of a Mrs L[orin]g, who is the very Cleopatra to this Anthony of ours.”38

Howe’s army, composed of some of the finest troops in the world, was confronted by a motley hodge-podge of militia, frontiersmen, and Continental Regulars. No legitimate European officer considered Washington’s force— determined though its men might have been—“real soldiers” or a “real army” compared with the professional grenadiers, light infantrymen, guardsmen, light horse, royal artillerymen, and Hessian jaegers fielded by Howe. Yet, as at least one historian has pointed out, this ragtag bunch assembled by Washington constituted the true origin of the United States Army: “Within the year, it would be baptized by fire at Brandywine, grow through hard experience at Germantown, and come to maturity at Valley Forge. If Washington can be described as the army’s father, Howe might aptly be described as its nanny.”39 These experiences were giving birth to a nation that had the capacity and the willingness to defend itself.

Late on June 14, reports of the British advance arrived in Philadelphia. John Adams was not overly concerned by the news, writing to his wife that if the British were bold enough to capture the city, “they will hang a Mill stone about their Necks.” The opinionated Adams believed the seizure of the city would seriously hamper the British war effort and that its capture would force the evacuation of New Jersey. “The Jersey Militia have turned out, with great Spirit. Magistrates and Subjects, Clergy and Laity, have all marched, like so many Yankees.” Despite the hope he placed in the militia, Adams was also realistic. If Howe managed to cross the Delaware River and Washington was not there to stop him, Congress would need to leave Philadelphia and move “fifty or sixty Miles into the Country. But they will not move hastily.”40

Another four days passed, during which Howe did nothing more than skirmish, plunder the countryside, and build some earthworks. He had moved fewer than 10 miles. If Howe had any hope of capturing Philadelphia and returning to the lower Hudson River by September to assist Burgoyne, his actions did not reflect these intentions. The slow pace suited Adams, who seems not to have cared whether the city was taken or not: “We are under no more Apprehensions here than if the British Army was in the Crimea.” By sitting still during good campaign weather, Howe was essentially removing his army from the war effort. Confident in Washington’s abilities, Adams added, “Our Fabius will be slow, but sure.” Benjamin Rush, soon to be with Washington’s army as a surgeon, wrote to Anthony Wayne that the “Accts we receive daily of the Strength, discipline, and Spirit of our Army give us great pleasure.”41

When Washington failed to come down out of the mountains to offer battle, a disappointed Howe decided to give up on this approach and returned to New Brunswick on June 19. Howe quietly withdrew until he was far enough from Washington’s outposts to feel secure. They marched, wrote an American eyewitness, “without beat of drum or sound of fife. When his army had gotten beyond the reach of pursuit, they began to burn, plunder and waste all before them. The desolation they committed was horrid, and served to show the malice which marks their conduct.” Captain Johann Ewald confirmed this description when he wrote, “On this march all the plantations of the disloyal inhabitants, numbering perhaps some fifty persons, were sacrificed to fire and devastation.”42

Once the Americans realized what was occurring, Nathanael Greene’s division and Anthony Wayne’s Pennsylvania brigade initiated a pursuit that triggered some minor skirmishes. It also revealed more of the depredations being committed against innocent civilians. Colonel Persifor Frazer of the Pennsylvania Line later described what they found: “They have in many instances behav’d very cruel to the Inhabitants where they pass’d. A respectable woman they Hung by the Heels so long that when they took her down she liv’d but a few Minutes. Plunder and Cruelty Mark their steps where there is scarce a soul but Tories.”43

Howe’s sudden withdrawal perplexed many British officers, including Major Stuart. “We traced out 4 redoubts at Middebrook, and one to cover the Bridge at Hilsborough,” the officer wrote in a letter home to his father, “most of which were nearly finish’d, when, to our astonishment, we received orders to retire to Brunswick.” Stuart continued, “I am convinced that, from the redoubts built … and the pontoon bridge we incumbered ourselves with, we intended to establish a magazine there, and pursue our way to the Delaware … [but did not] for the fear of our escorts being attacked bringing provisions from Brunswick.” However, Stuart was quick to point out that all armies face this sort of danger. “The risk which all armies are liable to was our hindrance here, and had absolutely prevented us this whole war from going 15 miles from a navigable river.” Stuart concluded by commenting on Howe’s tactics: “These retrograde movements appear just as incomprehensible to us as they can possibly do to you, for both in a military and a political sense it seems highly injudicious to have maintained posts.” Howe abandoned posts that had cost the army nearly 2,000 men over the previous few months, including loyalist inhabitants of the region. Stuart was angry that those locals were left “unprotected and exposed to a cruel and implacable enemy … who have sought your protection and served you.”44

Howe’s intentions during this week in northern New Jersey are difficult to fathom. He moved thousands of troops and tons of equipment 10 miles and built three earthworks—only to return to where he started. Washington’s army was certainly no threat to Howe. Perhaps he really believed his move would draw the Continental Army down from the mountains to fight a traditional European battle. At no previous time during the war, however, had Washington obliged Howe in such a manner; Washington rarely fought a battle without defensive works on ground of his own choosing. Howe’s operation offered a good example of a professional British army conducting a half-hearted effort.

The tepid thrust into the countryside is more evidence Howe never meant to assault Philadelphia through New Jersey. The British fleet would carry his army into Pennsylvania, and that had always been his plan. At least some of Howe’s officers understood that crossing the Delaware by marching through New Jersey was never Howe’s purpose. One of his brigade leaders, Gen. James Grant, wrote to Gen. Edward Harvey, adjutant general of the British Army in England, “As Washington had it still in his power to cross the Delawar at Easton or Alexandria, it became evident that moving to Flemington, Prince Town, Trenton or Penington would not have the desired Effect of drawing the Rebells from their fastnesses. Remaining longer in the Jerseys,” Grant added, “could of course answer no good End, as we did not intend to pass the Delawar in Boats. It was therefore thought expedient to return the 19th to Brunswick & to proceed from thence on the more important operations of the Campaign.”45

John Adams in Philadelphia, meanwhile, regarded Washington’s seeming victory with glee. “The Tories in this Town seem to be in absolute Despair,” he gloated, “and are Chopfallen, in a most remarkable Manner.” Adams discussed the large Quaker population in the city: “The Quakers begin to say they are not Tories—that their Principle of passive Obedience will not allow them to be Whiggs, but that they are as far from being Tories as the Presbyterians.” The future president was also excited about the growing Continental army, writing, “We have now got together a fine Army, and more are coming in every day.”46