“The line moving on exhibited the most grand and noble sight imaginable. The grenadiers beating their march as they advanced contributed greatly to the dignity of the approach.”1

— Lt. Frederick Augustus Wetherall, September 11, 1777

By the middle of the afternoon on September 11, Gen. Howe’s veteran troops under the steady hand of Gen. Cornwallis were poised to deliver the crowning blow of Howe’s flanking strategy.

Sometime after 3:00 p.m., Capt. Johann Ewald “caught sight of some infantry and horsemen behind a village on a hill in the distance, which was formed like an amphitheatre.” A short time later, Capt. Alexander Ross, General Cornwallis’s aide-de-camp, delivered an order to Ewald to take the advance guard and attack the American infantry and cavalry spotted up ahead. The capable Hessian captain organized the advance guard with the 17th Regiment of Foot’s light company deployed on the left, the light company of the 42nd Highlanders deployed on the right, and the mounted jaegers positioned on the road in the center. The foot jaegers moved out front in skirmish order while the main line formed.2

The Americans spotted by Ewald and targeted for attack were not, as the Hessian believed, “behind a village,” but near the Samuel Jones farm buildings and Birmingham Meetinghouse, which the captain mistook for a small community. The patriots were elements of Col. Thomas Marshall’s 3rd Virginia Regiment, part of Brig. Gen. William Woodford’s brigade of Maj. Gen. Adam Stephen’s division, together with some of Col. Theodorick Bland’s light dragoons. The Virginians had deployed on the Jones property south of the Street Road - Birmingham Road intersection east of the latter road about one mile below Osborn’s Hill. Southeast of the intersection was the Jones woodlot. His brick farmhouse (which Ewald had also spotted) was another 150 yards farther south along Birmingham Road, and just south of the house was the family orchard. The Americans, first positioned in the woodlot and later in the orchard, enjoyed a slight advantage in elevation over the light troops immediately confronting them.

The British advance guard extended its line eastward as it advanced toward the American position in an effort to outflank Colonel Marshall’s 3rd Virginia Regiment. The regiment, explained one American officer in his memoirs, “having been much reduced by previous service, did not amount to more than a battalion; but one field officer, the colonel, and four captains were with it.”3 The Virginians opened a long-range small arms fire. Captain William Scott of the 17th Regiment of Foot’s light company recalled the effort to get around the American right. His company, he wrote, “received a fire from about 200 men in the orchard, which did no execution.”4

After watching Cornwallis’s men march through Sconneltown and returning home to check on his family, young Quaker Joseph Townsend passed through the moving British Army as he walked south down the Birmingham Road to Osborn Hill and down its southern slope toward Street Road. “We reached the advanced guard, who were of the German troops,” recalled Townsend. “Many of them wore their beard on their upper lips.” The youth, who was unaware that British troops also comprised the advance guard, recalled the opening moments of the battle after the Virginians had fired upon Ewald’s command: “The attack was immediately returned by the Hessians, by their stepping up the bank of the road alongside the orchard, making the fence as a breast work through which they fired upon the company who made the attack.”5 If Townsend’s recollections are accurate, some of the jaegers pushed far enough beyond Street Road to use the eastern embankment of the Birmingham Road as protection to fire into the Jones orchard.

Townsend continued, “From the distance we were from them (though in full view until the smoke of the firing covered them from our sight) I was under no apprehension of danger [from the American fire] especially when there was such a tremendous force coming on [Cornwallis’s division] and ready to engage in action.” Townsend observed the approaching British and German formations with deep interest: “[W]e had a grand view of the army as they advanced over and down the south side of Osborne’s Hill and the lands of James Carter, scarce a vacant place left…. [A]lmost the whole face of the country around appeared to be covered and alive with these objects.” By this time the novelty of examining the British Army had worn off and it dawned on the youngster that he had walked directly into the middle of a growing battle: “I concluded it best to retire, finding that my inconsiderate curiosity had prompted me to exceed the bounds of prudence.” The Quaker turned northward, and walked back alongside the Birmingham Road.6

The opening and wildly inaccurate American fire hit but two of his men, which in turn allowed Ewald to push ahead and reach one of the buildings on the Jones property with both his foot and mounted jaegers. At that point the firing intensified. “Unfortunately for us,” explained Ewald, “the time this took favored the enemy and I received extremely heavy small-arms fire from the gardens and houses.” The sharp fire and firm stand offered by the Virginians, who may have been more numerous than Ewald originally believed, convinced the captain to pull his jaegers and the two British light companies back to the fence line along Street Road. The Americans let them fall back without advancing in return.7

It was at this time that Ewald realized his advance guard was more than living up to its name. Indeed, it was now much too far in advance of the balance of Cornwallis’s division. “They [the other members of the advance guard] shouted to me that the army was far behind, and I became not a little embarrassed to find myself quite alone with the advanced guard,” reported the Hessian. “But now that the business had begun, I still wanted to obtain information about these people who had let me go so easily.”8

Once he was satisfied with his new fallback position, Ewald took three men and rode well to the right (west) in an effort to better scout the American position. His initial route carried him to the top of a small hill southwest of the Street Road-Birmingham Road intersection. What he beheld stunned the veteran officer: “I gazed in astonishment when I got up the hill, for I found behind it—three to four hundred paces away—an entire line deployed in the best order, several of whom waved to me with their hats but did not shoot. I kept composed, examined them closely, rode back, and reported it at once to Lord Cornwallis” via a mounted jaeger named Hoffman. Ewald’s reconnaissance discovered Lord Stirling’s division in line less than one-half mile farther south on Birmingham Hill. Lieutenant William Keugh of the 44th Regiment of Foot, who was far behind Ewald at this time, would recall the strength of this American position and describe the terrain as “Hills which Nature Unassisted, had abundantly fortified.” Lieutenant Colonel Ludwig von Wurmb remembered Cornwallis receiving Ewald’s report back on Osborn’s Hill: “Captain Ewald of the advance guard reported the enemy was approaching and they were forming up on a hilltop and that another column was approaching on the right.” Captain Scott, whose company of the 17th Regiment of Foot was part of the advance guard that afternoon, took note of additional American troops when he observed, “it was evident tho’ the enemy fell back they were well supported.”9 The “additional” troops were the now very visible divisions of Stephen and Stirling forming farther south along Birmingham Hill.

Ewald was one of the first to see and realize the formidable nature of the American position, and that the Virginians on the Jones farm were not a small picket or advance force, but part of much larger command. It is likely that both Howe and Cornwallis believed the Americans were by this time retreating from their former position east of the Brandywine, their exposed flank turned and a strong force under Gen. Wilhelm von Knyphausen pressing their rear. Now they learned the truth: the Americans had simply maneuvered northward with a strong force to blunt Howe’s flanking effort. The British would not be dropping into Washington’s rear area without a fight.

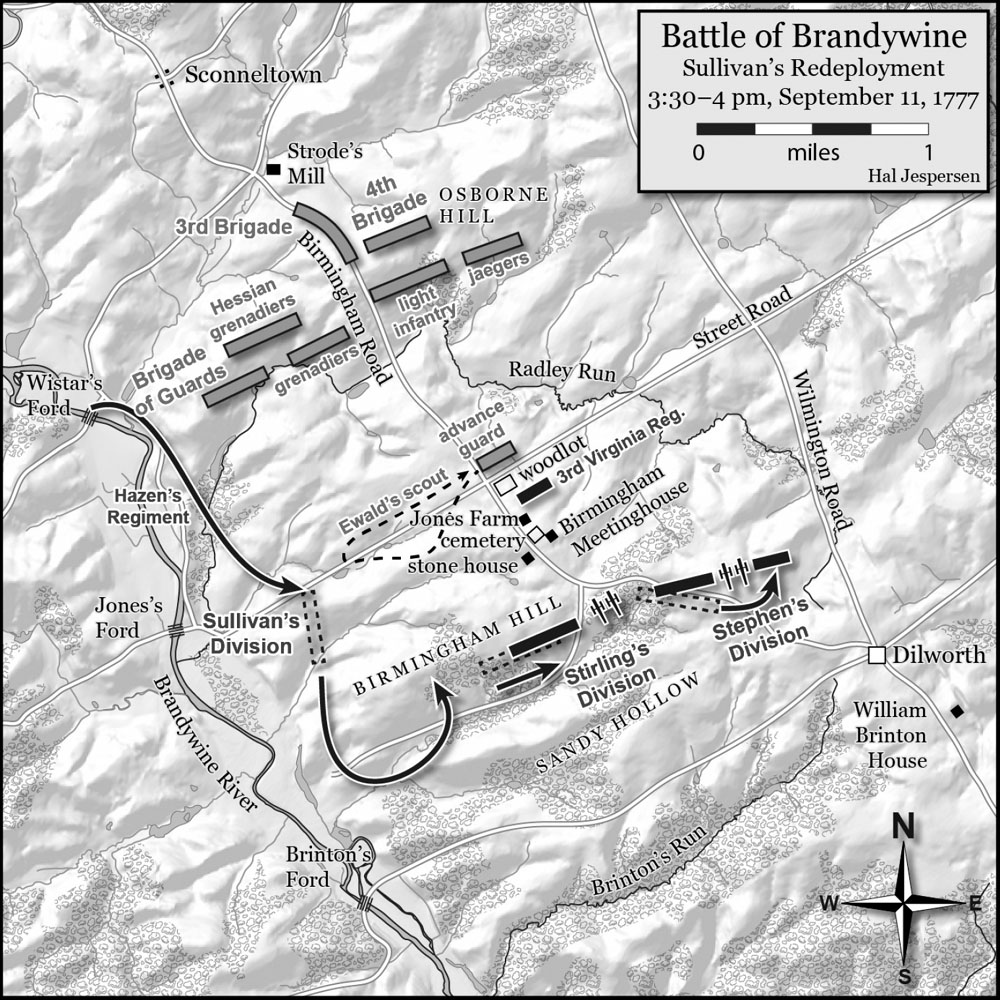

After sending his report to Cornwallis, Ewald continued his reconnaissance by riding down the hill and then west along Street Road toward Jones’s Ford. He spotted more American troops as he approached the crossing—“a whole enemy column with guns marching through the valley in which Lord Cornwallis’s column had been marching for some time, a quarter or half an hour away to the right.” The “enemy column” was Moses Hazen’s regiment marching south to link back up with the rest of Maj. Gen. John Sullivan’s division, which was approaching Street Road on its march from Brinton’s Ford. Hazen would fall in with the division and continue the march to unite with the divisions on Birmingham Hill. “[T]he Enemy headed us in the Road about forty Rods from our advance Guard,” reported Sullivan. “I then found it necessary to turn off to the Right to form & to get nearer to the other two Divisions [Stirling’s and Stephen’s] which I that moment Discovered Drawn up on an Eminence both in the Rear & to the Right of the place I was then at.”10

Sullivan’s change of direction moved his division onto the same hill Ewald had used just minutes earlier to observe Stirling’s position. The other two American divisions were deployed on Birmingham Hill about one-half mile to Sullivan’s right and rear. His division was the last major piece of the American blocking force, which was now aligned, by division, from left to right as follows: Sullivan, Stirling, and Stephen, with Sullivan in command of all three. Although most of three divisions had succeeded in shifting north at the last moment to meet Howe’s substantial flanking column, argues one historian, “these hurried alterations were liable to dent inexperienced troops’ confidence.”11

Ewald, meanwhile, returned to the advance guard still pinned down along the fence line near the Street Road-Birmingham Road intersection. His hurried ride had discovered Stirling’s division to his right front, and the arrival of more enemy troops in that quarter. Cornwallis had been duly informed. Now back with his men, the Hessian oversaw the fitful skirmish fire for which his men were famous, and awaited orders. He would not have long to wait. With the information from Ewald’s reconnaissance in hand, Howe directed Cornwallis to “to form the line.” Within minutes the columns of soldiers redeployed into crisp, heavy lines of battle. It was time to brush aside the incompetent Americans and drive into the rear of Washington’s imperiled army.12

Cornwallis’s division (excluding elements of the 16th Light Dragoons and the 3rd British Brigade, which initially remained on Osborn’s Hill with Gen. Howe), moved in column down the southern slope of Osborn’s Hill in preparation for its attack. It was about 4:00 p.m., and Howe’s Hessian aide, Friedrich von Muenchhausen, was there to witness it: “Our two battalions of light infantry and the Hessian Jagers marched down the hill. They marched first in a column, but later, when they approached the enemy, in line formation, deploying to the left.” To the right of the light infantry, von Muenchhausen continued, “the English grenadiers did the same in the center, almost at the same time.” Joseph Townsend, who had earlier approached Street Road and watched the opening of the fighting between the Virginians and Ewald’s advance guard, was walking back through the British formations at this time. Among the troops, he wrote, “the hurry was great, and so many rushing forward under arms.”13

Once Cornwallis’s advancing columns reached the farm fields at the bottom of the slope, commands rang out to form lines of battle on both sides of the Birmingham Road. The general’s plan of attack called for two lines of battle supported by a strong reserve. The front line included his elite troops. The Hessian and Ansbach Jaegers commanded by Lt. Col. Ludwig von Wurmb anchored his far left east of the road. The British light infantry brigade formed next to the Germans on their right, with Maj. John Maitland’s 2nd Battalion on the left and Col. Robert Abercromby’s 1st Battalion on the right. Maitland’s 14 companies deployed in fields sprinkled with light stands of timber. His remaining company, detached from the 42nd Royal Highlanders, was still in front skirmishing with Capt. Johann Ewald’s advance guard. Abercromby’s 1st Battalion, meanwhile, formed in the fenced fields immediately along the Birmingham Road with its right resting on the road itself. Behind this first line of the left wing was a second line of battle, or a reserve for the front line troops, comprised of Brig. Gen. James Agnew’s 4th British Brigade. This left wing, roughly 3,000 troops, would advance directly south against Adam Stephen’s well-placed division of 2,100 men on Birmingham Hill about one mile distant. Cornwallis’s right front deployed west of the Birmingham Road. Extending the front line in that direction were two battalions of British grenadiers. The 16 companies of Lt. Col. William Medows’s 1st Battalion formed in front, while the 2nd Battalion’s 15 companies led by Col. Henry Monckton formed behind them. The left flank of the grenadiers abutted the road. Cornwallis anchored his right with Brig. Gen. Edward Mathew’s British Brigade of Guards, with the 1st Battalion on the far right and the 2nd Battalion on the left next to the grenadiers. The Guards light company spread in front of the two battalions, with the Guards grenadier company holding the position of honor on the right of the line. The British light infantry and the Guards were about 200 yards farther advanced than the British grenadiers.14

Behind this first line of the right wing was a second line of battle (or reserve) comprised of the Hessian grenadiers under the overall command of 45-year-old Col. Carl von Donop, the son of a noble family and distinguished veteran of the Seven Years’ War. The von Minnigerode Battalion tramped behind the Brigade of Guards, with the von Lengerke Battalion and the von Linsing Battalion stretching the line eastward behind the British grenadiers (with the von Linsing on the left closest to the road). Cornwallis’s right wing, about 3,700 veteran troops, would attack south about one mile and strike Lord Stirling’s and John Sullivan’s divisions, some 3,200 strong, deployed atop Birmingham Hill.15

Behind these lines marched the deep reserve comprised of the 3rd British Brigade under Maj. Gen. Charles Grey, the 42nd Regiment of Foot under Lt. Col. Thomas Stirling, and the pair of squadrons of the 16th Light Dragoons. Although the historical record is unclear, it is reasonable to assume that these commands remained in column on the road for ready movement and rapid deployment, as circumstances dictated. The squadrons of the 16th Light Dragoons would later be ordered to assume a reserve position behind the Brigade of Guards.

One of the most impressive scenes to ever play out on the North American continent was unfolding on these Chester County farm fields. “Put on your caps,” yelled Lt. Col. William Medows to his grenadiers west of the Birmingham Road, “for damned fighting and drinking I’ll match you against the world!” The grenadiers took off their cloth forage caps, pulled their bearskin caps from their packs, brushed the fur, and placed them atop their heads. The imposing headgear added more than a foot to the already physically imposing men. Buttressed between the two battalions of British grenadiers were 62 drummers and British fifers. Drums, trumpets, whistles, and small brass hunting horns sounded the advance from both ends of the British lines. One historian painted the scene thusly: “Drumsticks dropped in one crisp motion, and a visceral thunder of drums rumbled out as 1,200 grenadiers stepped off together in a mesmerizing, glittering mass.” After a few steps, the impressive array of drummers and fifers began playing “The British Grenadiers,” which “shrilled across the once peaceful Quaker landscape, above the relentless, reverberating throb of drums.” Lieutenant William Hale of the British 45th’s grenadier company long remembered the impressive scene and would live through the day to write about it: “Nothing could be more dreadfully pleasing than the line moving on to the attack; the Grenadiers put on their Caps and struck up their march, believe me I would not exchange those three minutes of rapture to avoid ten thousand times the danger.” Yet another British officer recalled that the “line moving on exhibited the most grand and noble sight imaginable. The grenadiers beating their march as they advanced contributed greatly to the dignity of the approach.”16

As the light infantry battalions advanced steadily south, their line of battle perpendicular to the Birmingham Road, the majority of Lieutenant Colonel Wurmb’s jaegers shifted farther west and moved ahead through heavier, broken wooded terrain on the far left of Cornwallis’s advancing division. Royal artillery pieces moved ahead with the German troops—a pair of small 3-pounders supported by Lt. Balthasar Mertz and 30 grenadiers—as did two amusettes, described as “large, heavy muskets capable of lobbing 1-inch balls several hundred yards.”17

The early part of the advance proceeded smoothly except for a number of fences cutting across the front. Each of these barriers had to be climbed or torn down, which slowed the advance and required the realignment of the lines of battle before pressing ahead. The grenadiers confronted eight stout Pennsylvania fences between Osborn’s Hill and the American lines on Birmingham Hill.

A thankful if anxious Capt. Ewald watched the advance of Cornwallis’s division with deep interest. It was approaching 4:30 p.m., and his men had been holding their forward position, trading skirmish fire with the Virginians, for the better part of a very long hour. When the British and German front lines stepped within 300 or 400 paces of Street Road, Ewald ordered his advance guard to renew its assault against the American position on the Jones property. According to Ewald, “[f]rom this time on, I did not see one general. Where they were reconnoitering I don’t know.”18 Using the embankment and fences lining the east side of Birmingham Road, Ewald and his jaegers outflanked the Virginians holding the orchard and forced them to retire to the meetinghouse proper.

Townsend and his companions, meanwhile, were on their way back to Osborn’s Hill. They were walking along the fence line separating the Birmingham Road from the fields east of it when a German officer ordered Townsend to take the fence down. “As I was near the spot I had to be subject to his orders,” recalled Townsend, “as he flourished a drawn sword over my head with others who stood nearby.” It wasn’t until the youth was removing the rails that it occurred to him he might be violating his pacifist Quaker tenets. “As the hurry was great, and so many rushing forward under arms, I found no difficulty in retiring undiscovered and was soon out of reach of those called immediately into action,” he explained.19

Once Cornwallis’s front lines reached a point about halfway between Osborn’s Hill and Birmingham Hill (approximately where Street Road crossed their path), American artillery rounds began to find their range. The extreme range of the American 3- and 4-pounders firing solid shot was only about 1,200 yards, but late that afternoon that was enough, and the exploding shells wounded many British troops, some mortally. “Some skirmishing began in the valley in which the enemy was drove,” reported Capt. John Montresor, “upon gaining something further of the ascent the enemy began to amuse us with 2 guns.” The valley mentioned by Montresor was Carter’s open farm field between Osborn’s Hill and Birmingham Hill, and the Americans were using more than just a pair of artillery pieces on the British formations. Five American artillery pieces were firing from the knoll separating Stirling’s division from Stephen’s position. The gunfire was not enough to seriously disrupt the advancing professionals, who continued apace southward toward Birmingham Hill. When they stepped within 500 yards, however, the Americans switched to grape and canister rounds, which were more effective as anti-personnel weapons.20

In an effort to silence the American guns and soften the enemy infantry positions, the British rushed forward guns from the 4th Battalion of the Royal Artillery, 6- and 12-pounders that probably deployed along Street Road.21 The small arms fire combined with heavy bluish-white clouds of artillery gun smoke to limit visibility and obscure formations. Artillery rounds arced through the muggy Pennsylvania air before dropping among the Continentals, shearing off tree branches and sending splinters large and small of both iron and wood flying in every direction. Whizzing hot chunks of iron dismembered some, and crushed and killed others. Grapeshot belched from the smaller battalion guns ripped through the American ranks of both Lord Stirling’s and Adam Stephen’s divisions and wreaked similar havoc. Private John Francis, “a negro” in the 3rd Pennsylvania Regiment, wrote one eyewitness, “had both legs much shattered by grape shot,” and another member of the same regiment, Ensign William Russell, lost a leg from a cannonball. Both belonged to Thomas Conway’s brigade (Stirling’s division). Stacey Williams, “a negro private” in the 6th Pennsylvania Regiment, also part of Conway’s command, fell with a wound in the right thigh, as did a sergeant from the same regiment. The day after the battle, American artilleryman Elisha Stevens took a few minutes to write a description of the gruesome scene he had witnessed the previous day. “Cannons roaring, muskets cracking, Drums Beating Bombs Flying all Round, men a dying & wounded Horred Grones which would Greave the Hardest of Hearts to see,” he lamented. “[S]uch a Dreadful Sight as this to see our Fellow Creators [creatures] slain in such a manner as this.”22 The American artillerymen, however, weathered the deadly storm of iron and stuck to their pieces. Their steady firing found the range and opened gaps in the advancing British line of grenadiers.

While Cornwallis’s division was slow-stepping its way down Osborn’s Hill in all its sublime grandeur, John Sullivan’s division was moving south to get into a line of battle on Birmingham Hill. Part of the problem bedeviling the command that day was its lack of senior leadership. When Sullivan was temporarily elevated to command the right wing of the American army (he was to assume command of all three divisions once he arrived upon Birmingham Hill), the commander of the 2nd Maryland Brigade, Brig. Gen. Phillipe Hubert de Preudhomme de Borre stepped into Sullivan’s boots to lead the division. The brigade’s senior colonel was Moses Hazen, but it is unclear whether Hazen’s regiment (which had been on detached duty watching Wistar’s Ford and would be tasked with protecting the artillery at the tail end of the division) ever rejoined the brigade or instead fought the battle independently. The commander of the 1st Maryland Brigade, Brig. Gen. William Smallwood, was on detached duty in Maryland raising militia (as was his senior colonel, Mordecai Gist). The record is unclear who commanded the brigade in their absence. Presumably it was John Stone, the colonel of the 1st Maryland Regiment, who had only been a colonel since that February. The result of this command shuffling put the division under a disliked French officer few Americans could understand, and both brigades in the hands of less capable junior colonels.23

Once Sullivan reached the area and formed his division into line east of Jones’s Ford and south of Street Road, he realized he had taken up a position well in front and west of the other two American divisions. This left his command exposed to being turned on either flank and crushed, too far away to lend ready help to the remaining divisions on his right, and too far removed for either Lord Stirling or Stephen to assist him. Sullivan had no choice but to reposition his division. It was probably at this point that he turned command of the division over to Gen. de Borre with orders to move the division south to Birmingham Hill. Once arranged, Sullivan rode southwest to inform Stirling and Stephen that he was in command of all three divisions, and discuss how best to align the front once his own division arrived. From the information they shared, together with a view of the field, Sullivan realized the British, in the form of the jaeger corps, were in a position that could outflank the right side of the American line. The entire line, urged Sullivan, including his own division, “[s]hould Incline further to the Right to prevent our being out flanked.”24 Sullivan was correct, but the difficult movement would have to take place during the British advance toward Birmingham Hill.

What might look easy drawn on a map or scratched into the dirt with a stick rarely was in practice. The American soldiers were not yet veterans, and accomplishing such a maneuver under enemy fire was sure to be difficult. Nevertheless, Stirling and Stephen managed to shift their divisions several hundred yards to the right without substantial difficulty. Howe and Cornwallis spotted the maneuver and countered the patriot move by ordering the 4th British Brigade to leave its reserve position and form on the left flank of the jaegers, extending the line a significant distance in the same direction. The 3rd British Brigade was also called up from its reserve position on the road and deployed into a direct supporting position behind the light infantry west of the road. What was relatively uneventful for Stirling’s and Stephen’s divisions, however, proved to be nearly disastrous for Sullivan’s division under de Borre.25

After his consultation with Stirling and Stephen, Sullivan rode back in search of his division, which he found moving south but still some distance from Birmingham Hill. Sullivan, as he later explained, “ordered Colo. Hazens Regiment to pass a Hollow way, File off to the Right & face to Cover the Artillery while it was passing the Same Hollow way, the Rest of the Troops followed in the Rear to assist in Covering the Artillery the Enemy Seeing this did not press on but gave me [Sullivan] time to form my Division on an advantageous Height in a Line with the other Divisions but almost half a mile to the Left.”26 Hazen’s regiment covered the division’s artillery and thus constituted the tail end of the division.

Once his division was on Birmingham Hill, however, Sullivan realized yet again he was out of position because a large gap existed between his right and Lord Stirling’s left. Once again, Sullivan sought out Stirling and Stephen, leaving de Borre to shift the division to the right (eastward) to better align it with Stirling’s command. Several histories of the battle insist Sullivan demanded his division be placed on the far right of the line in what was considered the position of honor. Contemporary accounts, however, agree that Sullivan ordered his division onto the left flank of the American line as a matter of military necessity.27