Among those withdrawing within the remnants of Sullivan’s own division was Col. John Stone of the 1st Maryland Regiment, who remembered the arrival of patriot reinforcements and what would be the forming of a final line of resistance. “[We] retreated about a quarter of a mile and rallied all the men we could,” reported the colonel, “when we were reinforced by Greene’s and Nash’s corps, who had not till that time got up. Greene had his men posted on a good piece of ground.” The final stage of the Brandywine battle was about to begin.13

Pickering, Washington, and other members of the staff (probably in the vicinity of the William Brinton House) were well in front of where Nathanael Greene would eventually form, watching the disorganized retreat of the divisions coming from Birmingham Hill while Knox put up a brave show of resistance with a pair of artillery pieces. It was at this time, as Pickering would note, that the decision was made to form Greene’s men, who were arriving to protect the avenue of retreat. “We retreated farther,” Pickering recalled. “Col. R. K. Mead[e], one of the General’s aids, rode up to him about this time, and asked ‘if Weedon’s brigade [one of Greene’s two Virginia brigades], which had not yet been engaged, should be ordered up?’” At this critical moment, one of Washington’s officers saw him “within 200 yards of the enemy, with but a small party about with him & they drawing off from their station.”14

“Count Pulaski, a veteran of the Polish Army and another recently arrived volunteer in the cause, proposed that George Washington give him ‘command of his body guard, consisting of about 30 horsemen.’ Pulaski led them to the charge.” Or so popular histories of the battle recount. Did Pulaski perform this daring feat to buy time for Greene’s division to get into position? Another version credits Pulaski with both making the charge and helping “to rally some of Sullivan’s men and oppose the British under General James Agnew.”15

Two other popular accounts, one by Samuel Smith and the other by Thomas McGuire, outline the same event in some detail, and both rely upon the 1824 book Pulaski Vindicated from an Unsupported Charge, Inconsiderately or Malignantly, by Louis Hue Girardin and Paul Bentalou:

Count Pulaski proposed to Gen. Washington to give him command of his body guard, consisting of about thirty horsemen. This was readily granted, and Pulaski with his usual intrepidity and judgment, led them to the charge and succeeded in retarding the advance of the enemy—a delay which was of the highest importance of our retreating army. Moreover … Pulaski soon perceived that the enemy were maneuvering to take possession of the road leading to Chester, with the view of cutting off our retreat, or, at least, the column of our baggage. He hastened to General Washington, to communicate the information, and was immediately authorized by the commander in chief to collect as many of the scattered troops as he could find at hand, and make the best of them. This was most fortunately executed by Pulaski, who, by an oblique advance upon the enemy’s front and right flank, defeated their object, and effectually protected our baggage, and the retreat of our army.”16

This source is especially interesting because Bentalou was a lieutenant in the German Regiment, part of Gen. de Borre’s brigade (Sullivan’s division). Bentalou fought at the Brandywine, and thus could have witnessed the scene. His regiment was among those scattered when the British Guards attacked Sullivan’s division, so he was on that part of the field. Whether he was in a position to witness Pulaski’s supposed act is unknown. It should also be taken into account that Girardin and Bentalou published their book five decades after the battle, which makes its reliability suspect. Neither Washington nor anyone who was present on that part of the battlefield during the closing phase mentioned Pulaski’s heroics at the time or thereafter, and no British or Hessian source mentions any type of cavalry charge by the Americans during any point in the battle. Unless a contemporary source corroborating Pulaski’s deed surfaces, the story of his heroic charge is open to reasonable doubt.

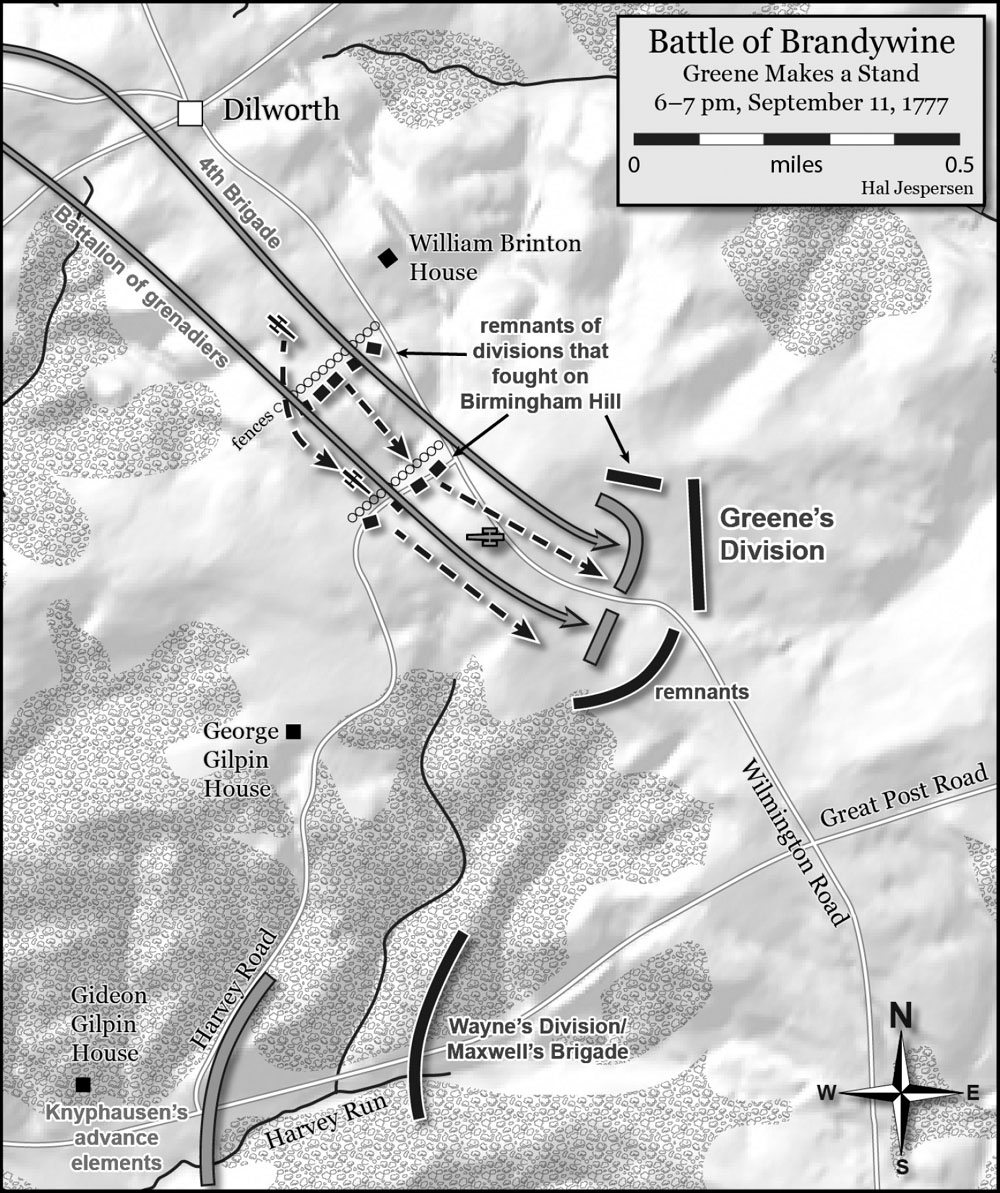

The last elements of Lord Stirling’s and Adam Stephen’s commands were being driven from Birmingham Hill (about 5:00 p.m.) when Washington ordered Nathanael Greene’s division of two brigades to leave its position east of Chads’s Ferry and march northeast about two and one-half miles to reinforce the embattled flank. Greene’s division set off with Brig. Gen. George Weedon’s brigade in advance, followed by another under Brig. Gen. John Peter Muhlenberg, entered the Great Post Road and marched east, turned northeast on Harvey Road toward Dilworth, and arrived near the intersection with the Wilmington Road (modern-day Oakland Road) about 6:00 p.m. According to Greene, he “marched one brigade of my division … between three and four miles in forty-five minutes. When I came upon the ground I found the whole of the troops routed and retreating precipately, and in the most broken and confused manner. I was ordered to cover the retreat, which I effected in such a manner as to save hundred[s] of our people from falling into the hands of the enemy.”17

South Carolinian Charles Cotesworth Pinckney, a colonel on leave from his unit in Charleston, was attached to Washington’s staff that day. Long after the battle he recalled seeing Greene’s division arrive on the northern end of the battlefield. “Sullivan proposed to the General [Washington] to halt it there & to display & take the Enemy in flank as they came down,” recalled Pinckney. “This Genl Washington acceded to, & I was directed to carry the orders.” Sullivan, Pinckney continued, “turning to me, requested I would ride up to General Weedon, and desire him to halt Colonel [Alexander] Spottswood’s [Spotswood] and Colo [Edward] Stephens’s [Steven’s] Regiments in the plough’d Field, on our right, & form there.”18

Pinckney set his spurs and delivered his instructions to Greene, who in turn ordered Gen. Weedon to move east of the Wilmington Road and align his men accordingly. While Greene was moving into position, the British continued advancing on Dilworth (on a line parallel to modern-day Brinton’s Bridge Road). The 4th British Brigade under Brig. Gen. James Agnew, which earlier had been ordered to fill the gap on the left of the 2nd British Light Infantry Battalion, took the place of the light infantry on the left of the British line east of the road. The brigade of about 1,400 men presented a grand and imposing front aligned right to left as follows: 37th, 64th, 46th, and 33rd Regiments of Foot. Just as Agnew’s men passed Dilworth, Hessian Capt. Johann Ewald reported the advancing lines “received intense grapeshot and musketry fire which threw the grenadiers into disorder.” The grenadiers thrown into “disorder” belonged to the 2nd British Grenadier Battalion. The advancing British angled to their left (east) to avoid the raking fire from Knox’s pair of guns, and eventually halted to realign their front and await artillery support. Within a few minutes, the Royal Artillery rolled forward with three 12-pounders, unlimbered, and opened fire upon Knox’s pair of advanced artillery pieces. The American artillerist withdrew his pair of light guns a short distance south, unlimbered a second time, and continued the action.19

General Sullivan, meanwhile, was riding to and fro reforming knots of retreating soldiers along a fence behind Knox’s guns, where they remained but a short while before falling back farther south. He was aligning his survivors when an enemy round struck and killed his horse from under him. Some of his men streamed through and temporarily disrupted Greene’s arriving men, while others shook out a rough though weak line of battle on a cleared piece of rising ground southwest of the Wilmington Road-Harvey Road intersection. Captain Francois Fleury, one of Sullivan’s brigade majors, later wrote that some of these survivors formed “near the Road, behind a House, to the left of General Green’s Division.” Other survivors from the Birmingham Hill disaster had streamed east of the road and were then forming on what would be Gen. Weedon’s right flank in a thick stretch of woods.20

While Knox worked his guns and Sullivan attempted to salvage something from his shattered command, American officers shouted out orders to their men to form a line on the reverse slope of a rise about one mile southeast of Dilworth. Despite the tight window of time he had to march his command northeast into a blocking position and then effectively deploy his men, Nathanael Greene succeeded on both counts. His division numbered about 2,500 men, but the exact composition of his final line of battle, and how many made it into that line in time to engage the approaching British, remains a subject of historical debate. According to Col. Pinckney, it was Gen. Sullivan who suggested the general location of Greene’s final line, and that Weedon move east of the road (the American right) and form there. Sullivan was on this part of the field (and thus enjoyed some familiarity with it) before either Washington or Greene arrived. He knew the axis of the British advance (south) from Dilworth. The rising terrain, coupled with heavy woods on the right, would make the proposed line all but invisible to the approaching enemy. The location of the final line made good tactical sense. Pinckney’s detailed account has verisimilitude.21

The Wilmington Road bisected the final line of battle. General Weedon’s brigade, with survivors from the Birmingham Hill disaster, formed Greene’s right wing east of the road. In its final form, this part of the front settled into an L-shaped formation with both ends anchored in woods. The long stem of this L-shaped formation faced generally west and was likely comprised of Weedon’s Virginia regiments and the Pennsylvania State Regiment. The shorter leg was probably comprised of remnants from Stirling’s and Stephen’s divisions. This shorter front was ensconced along a line of woods nearly perpendicular to Weedon’s front and faced south. Each end of the L-shaped line was refused, with the far right running deep into the stand of woods, and the other end running for a short distance along a fenceline bordering the Wilmington Road.22

The composition of Greene’s left wing west of the road is much more problematic. Archibald Robertson’s invaluable manuscript map depicts a heavy line of battle west of the road, which faced and blunted the advance of the 2nd Grenadier Battalion. But who fought in this line? Both Gens. Sullivan and Greene later wrote that only Brig. Gen. George Weedon’s brigade (from Greene’s division) was engaged that evening on this part of the field. Greene, who did not leave a report or extended account of his actions at Brandywine, mentioned in a letter that he marched north with only one (Weedon) of his two (Weedon and Muhlenberg) brigades. There are no primary accounts from Gen. Muhlenberg or anyone from his brigade regarding this issue. It is unlikely, however, that Muhlenberg remained on the southern part of the field, and indeed must have marched northeast behind Weedon’s regiments. If he did so, it is equally likely that, with Weedon formed (or already fighting) east of the road as Greene’s right wing, as the trailing organization Muhlenberg would have deployed his command west of the road with Sullivan’s survivors gathered into line from the three divisions driven from Birmingham Hill.23

This line that formed west of the Wilmington Road sketched a wide concave tree-lined front facing generally northwest. This line was also a short distance farther west than Greene’s right (Weedon), and a gap of perhaps 100 yards, together with the road itself, separated the two wings. Both wings enjoyed wide-open fields of fire against their approaching enemy. The terrain, woods, fences, and growing shadows guaranteed the advancing British troops in general, and Agnew’s 4th Brigade in particular, would move into a crossfire before seeing or realizing the full extent of the Continental line. The result, which could not have been by accident, was a giant killing box.24

Washington did not intend for Greene to make his stand alone. Soon after leaving the Chads’s Ford area, Washington concluded his right was in more danger than he originally believed, and decided to call up Brig. Gen. Francis Nash’s North Carolina brigade for more support. He sent the army’s adjutant general, Timothy Pickering, to deliver the order. Once he did so, Pickering “fell in with Col. Fitzgerald, one of the Generals’ [Washington’s] aids, and we galloped to the right where the action had commenced, and as we proceeded, we heard heavy and uninterrupted discharges of musketry (and doubtless of artillery) but the peals of musketry were most stricking.”25

Agnew’s 4th British Brigade, meanwhile, remained stalled outside Dilworth just west of the road and facing generally south while the 2nd British Grenadier Battalion advanced alone toward the American position. Captain Ewald gathered together his surviving jaegers from his advance guard and attached himself to the tramping grenadiers. Captain-Lieutenant John Peebles, a member of the Scottish 42nd (Royal Highland) Regiment of Foot’s grenadier company, recalled their advance and came up against a “second & more extensive line of the Enemys best Troops drawn up & posted to great advantage, here they sustain’d a warm attack for some time & pour’d a heavy fire on the British Troops as they came up.”26

The discovery of a strong and perhaps unexpected line of American resistance sent Ewald riding rearward in search of reinforcements. When the intrepid Hessian found Gen. Agnew and the 4th British Brigade at a standstill well to the rear, he “requested him to support the grenadiers, and pointed out a hill which, if he gained it, the enemy could not take the grenadiers in the flank.” Agnew, whose command was near Dilworth on the western side of the Wilmington Road, agreed and ordered his troops to move out. His brigade marched from right to left as follows: 37th, 64th, 46th, and 33rd Regiments of Foot, with the left flank of the 33rd aligned along the edge of the Wilmington Road. His troops moved rapidly south past the William Brinton house in an effort to come up with the 2nd Grenadier Battalion’s left flank. The brigade continued its steady tramp until clear of a large point of woods, south of which the road continued on for some distance before carving its way east toward the American position. With the grenadiers advancing ahead and well to his south and right, Agnew swung his line in a large left wheel until it faced generally east. Five companies of 2nd Light Infantry Battalion joined Agnew’s line by squeezing into position between the 33rd and 46th regiments. When all was as he wanted it, Agnew ordered his regiments across the Wilmington Road, and pushed them up the slope to come up on the left flank of the grenadiers. “[W]e had no sooner reached the hill,” explained Ewald, “than we ran into several American regiments.”27

Most of the roughly 2,000 British and Hessian troops advancing into the interlocking fields of fire across Greene’s expansive front were thoroughly exhausted after their hard marching and bloody fight for Birmingham Hill. The sudden discovery of Greene’s troops formed on both sides of the road in good order and in strong lines took them by surprise, and gives further meaning and context to grenadier Peebles’s recollection of meeting a “second & more extensive line of the Enemys best Troops drawn up & posted to great advantage.”28