The day following the battle, Washington began issuing orders in Chester to begin the reassembling of his army. Among other things, he ordered: “The commanding officer of each brigade is immediately to send off as many officers as he shall think necessary on the roads leading to the places of action yesterday, and on any other roads where stragglers may be found; particularly to Wilmington, where ‘tis said, many have retired, to pick up all the stragglers from the army, and bring them on. In doing this, they will proceed as far, towards the enemy, as shall be consistent with their own safety, and examine every house.” In addition to sending all the wounded who could be moved, together with the sick, to Trenton, Washington also ordered up a gill of rum or whiskey to every man in the ranks. Washington also needed to know the extent of his losses, and make sure his commands were ready to fight again, and quickly. To that end, he directed each “Brigadier, or officer commanding a brigade will immediately make the most exact returns of their killed, wounded and missing. The officers are, without loss of time to see that their men are completed with ammunition; that their arms are in the best order, the inside of them washed clean and well dried; the touch-holes picked, and a good flint in each gun…. The commanding officer of each regiment is to endeavour to procure such necessaries, as are wanting, for his men.”28

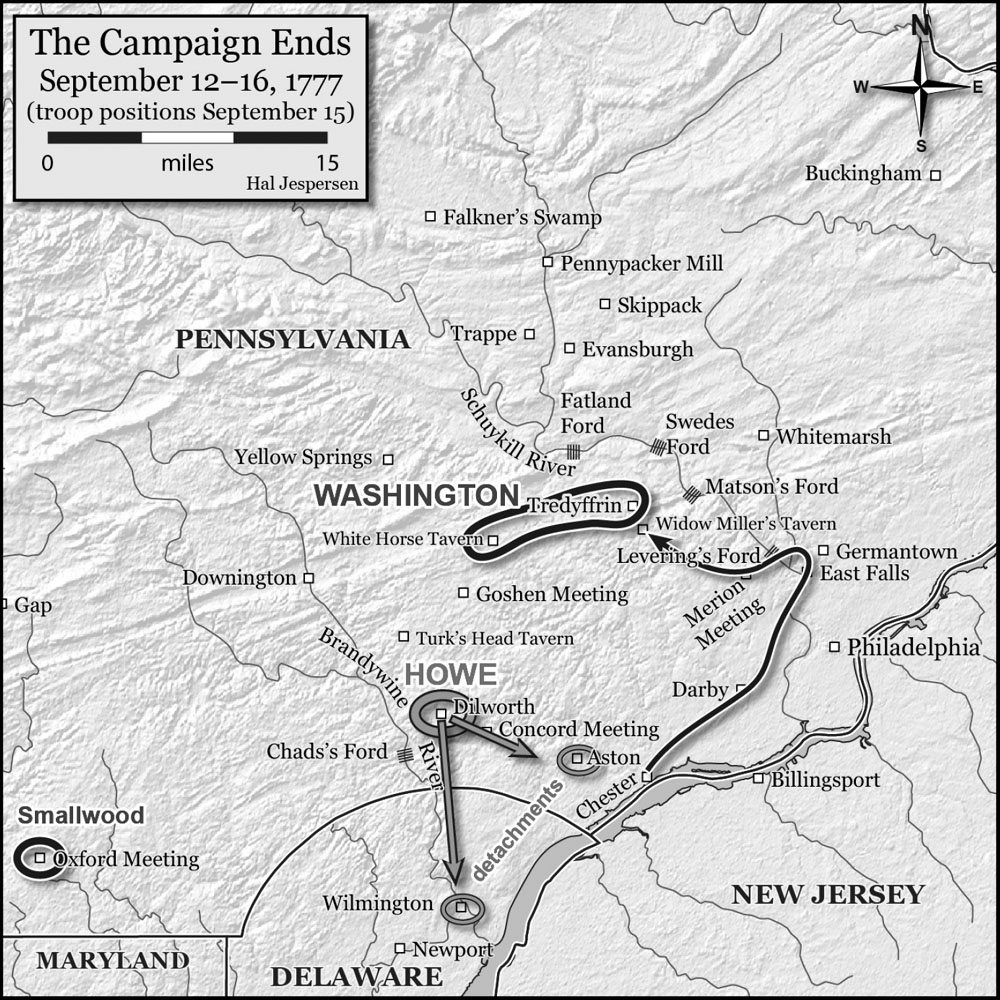

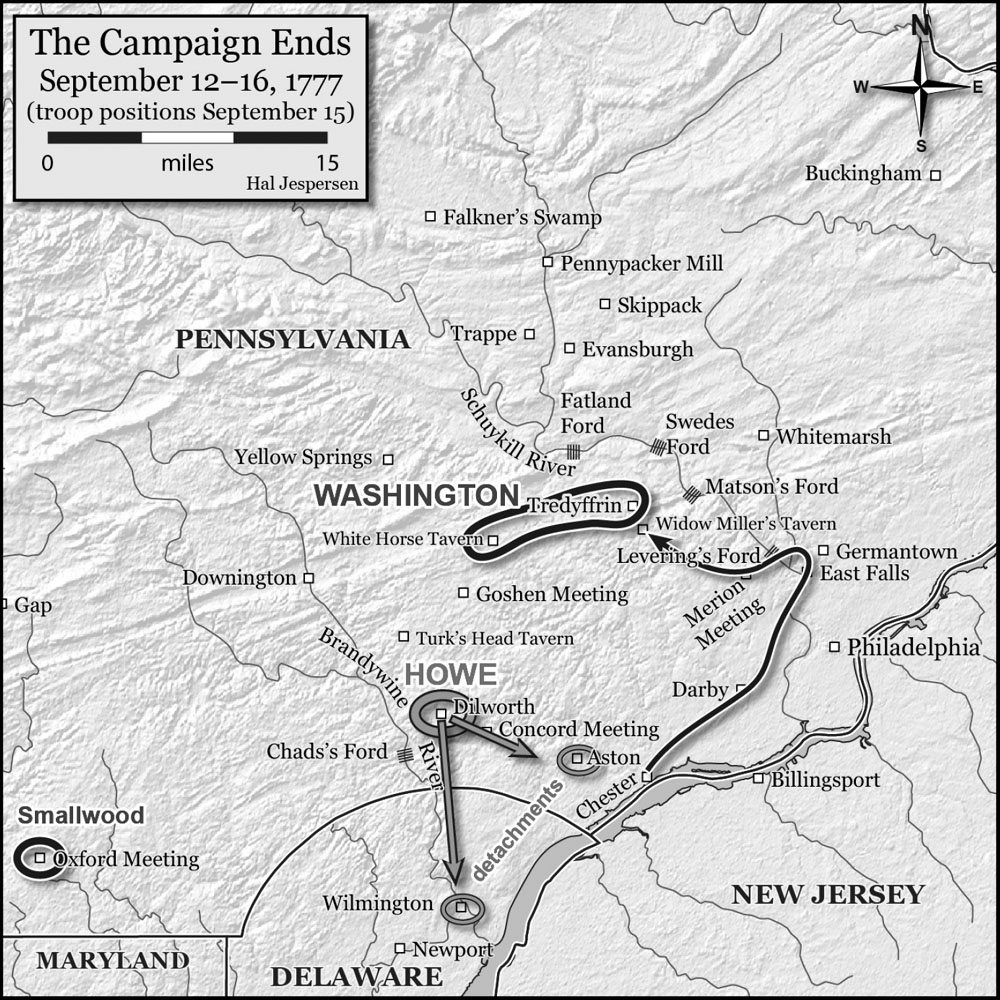

After dispatching these orders, Washington put the American army back on the road. He needed to find fresh defensive ground to meet Howe. The Continentals fell back from Chester through Darby, and marched on to the floating bridge at the Middle Ferry on the Schuylkill River (modern-day Chestnut Street), where it crossed. The marchers bypassed Philadelphia and moved to the Falls of the Schuylkill at East Falls, about five miles from the Middle Ferry in the vicinity of Germantown. He completed the entire move in a single day.

From Darby, Washington wrote to Brig. Gen. William Smallwood, who was gathering the Maryland militia around Oxford Meeting in southern Chester County. “It appears to me, that the Forces under your command, cannot be employed to so much advantage in any way, as by falling on the Enemy’s Rear and attacking them as often as possible. I am persuaded many advantages will result from this measure,” explained Washington. “It will greatly retard their march and give us time, and will also oblige them, either to keep a string guard with their Sick and Wounded, with which they must now be much incumbered, or to send them back to their Shipping under a escort, which you will have an opportunity of attacking with a good prospect of Success.” The set piece battle at Brandywine excepted, Washington’s strategy of harassing Howe’s army continued.29

Washington’s primary concern, and one that led him to risk his army along the Brandywine, was protecting Philadelphia. There was now just one natural barrier, the Schuylkill River, remaining between the city and Howe’s victorious army. Although swift-flowing, the Schuylkill was fairly shallow in the eighteenth century. The Falls of the Schuylkill were comprised of rapids that passed through large boulders where the river dropped some 30 feet. Except for a floating bridge, there were no permanent bridges spanning the river. However, Philadelphia was accessible at the Upper, Middle, and Lower ferries, and several fords were present farther upriver.30

Most of the fords on the Schuylkill were winding, narrow affairs that snaked across a gravelly river bottom and used islands or mud flats to span the river. Those fords would play a role in the future campaign included Levering’s, Matson’s, Swedes’, and Fatland’s. High hills surround the Schuylkill along much of its course, and many of the ford roads meandered down steep inclines. Any army crossing the river in this manner would find itself vulnerable against a well-positioned and alert opponent. The hills around Swedes Ford, however, were more gradual and the ford itself was located in a wide and shallow valley where the river bottom was hard and stony—all of which in turn provided more space for a large force to maneuver and better protect itself. Much as it was along the Brandywine River, all of the fords and ferries along the Schuylkill River would need to be defended if Philadelphia was to remain in American hands.31

Washington faced a difficult decision as he moved his army into the Germantown area. Philadelphia sits at the tip of a peninsula bordered on the east by the Delaware River and on the west by the Schuylkill River. Washington needed to defend the capital, but he could not afford to leave his supply depots at Reading and other places to the west unprotected. A move northwest to protect Reading would expose the city, while positioning his army to fight for the capital exposed his supply depots. Washington knew Philadelphia was difficult to defend, and once he lost at the Brandywine it was nearly impossible. He may have already made the decision to protect his storehouses to the detriment of the American capital.32

Panic, meanwhile, gripped Philadelphia. Many of its citizens had already fled, while others prepared for the worse (or, if their loyalties were elsewhere, rejoiced quietly as Howe’s army approached). When General Sullivan supposedly found documents in northern New Jersey claiming Quakers were plotting to aid the British, a number of that sect were arrested earlier in the month and confined in the city’s Masonic Lodge. With the combat at Brandywine concluded, they were released and sent away. Even though no formal charges were filed, Congress decided to remove these prominent Quakers from the capital.33

While Washington continued retreating on September 12 toward Germantown, parts of Howe’s army crept after him. General James Grant with the 1st and 2nd British Brigades, a squadron of dragoons, and the Queen’s Rangers led a reinforced scouting expedition two miles east of the battlefield to Concord Meeting to search for Washington’s army and round up stragglers. British horseflesh was still in deplorable condition. Phebe Mendenhall watched the British approach her family farm near Concord and later recalled that Grant’s troops “had the poorest little horses to pull their big guns, they couldn’t pull them up the big hill by the barn.”34

Other troops dispersed to find food or continued helping the wounded. Carl von Baurmeister remembered burying the dead that day and moving wounded to Dilworth, “where we found a flour magazine, from which the army was provisioned for two days.” Later in the afternoon, elements of the light dragoons and the fresh and relatively unbloodied 71st Highlanders were sent 10 miles beyond Dilworth to Wilmington to secure the town to help establish a rendezvous with the fleet. A general hospital was also established in Wilmington, where many troops injured along the Brandywine were eventually dispatched.35

Members of the 71st Highlanders promptly arrested John McKinley, the president of Delaware, upon entering Wilmington. According to McKinley, he remained behind because he was “more solicitous to perform my Duty, than for my own personal Safety.” The few American militia still in Wilmington’s defensive works fled when they spotted the approaching Highlanders. In addition to the capture of McKinley, they also seized seven artillery pieces. With Wilmington secured as a base of operations for the Royal Navy, Admiral Howe assured his brother “that he would have several ships at Wilmington on September 15th at the latest.”36

Other than these movements, Howe’s army remained idle on September 12. If the British general had aggressively pursued Washington’s beaten army, he may have been able to maintain the initiative, forced additional fighting on his terms, and crushed or otherwise further dispersed the Americans. He could also have crossed the Schuylkill River’s upper fords, as he would later do, and by doing so cut off Washington’s troops from their critical Reading depot. The last issue was especially important to Howe, who had earlier stated that capturing the patriot storehouses was one of the goals of his 1777 campaign. Thomas Paine, the author of Common Sense, wrote to Benjamin Franklin that “the enemy’s not moving must be attributed to the disability they sustained, and the burthen of their wounded. They move exceedingly cautious on new ground,” he continued, “and are exceedingly suspicious of villages and towns, and are more perplexed at seemingly little things which they cannot clearly understand than at great ones which they are fully acquainted with.” What Paine leaves unwritten was that Howe had a record of unenthusiastic follow-through in the aftermath of planning and waging successful battles. His army was also much more badly injured than many understood at the time, something Howe would only fully discover in the days immediately following the September 11 combat.37

With immediate matters in hand and having withdrawn far enough beyond Howe’s immediate range, Washington congratulated his army for its performance along the Brandywine two days after the battle. “The General, with peculiar satisfaction,” announced Washington in a set of general orders, “thanks those gallant officers and soldiers, who, on the 11th. instant, bravely fought in their country and its cause.” Although the battle, “from some unfortunate circumstances, was not so favorable as could be wished,” he continued, “the General has the satisfaction of assuring the troops, that from every account he has been able to obtain, the enemy’s loss greatly exceeded ours; and he has full confidence that in another Appeal to Heaven (with the blessing of providence, which it becomes every officer and soldier humbly to supplicate), we shall prove successful.” Once the orders were read to the troops, the more practical business at hand resumed, with militia elements constructing redoubts above the Schuylkill River fords and other units drilling and reorganizing their ranks.38

Howe, meanwhile, continued shifting his army about the vicinity of the Brandywine battlefield. Lord Cornwallis took the British light infantry and British grenadiers and joined Grant in the vicinity of Concord before marching to the heights at Aston within five miles of Chester. A few patrols probed to the outskirts of Chester without opposition. According to an unidentified officer serving in the 2nd Light Infantry Battalion, his unit spent September 13 marching “to Chester and on the Roade fell in With Several Out houses and Barns full of Wounded men Who tould us that If We keep on that Night We Should have put a total End to the Rebelion.” Howe also dealt with his sharpshooters. With Patrick Ferguson disabled, he ordered his riflemen to rejoin their respective light companies.39

On September 14, most of Washington’s army left the Germantown area, marched down Ridge Road, crossed the Schuylkill at Levering’s Ford, and moved to the Old Lancaster or Conestoga Road (modern-day U.S. Route 30). The army camped across a wide area from near modern Radnor at the Widow Miller’s Tavern to Merion Meeting. Washington established his headquarters at the Buck Tavern.

Timothy Pickering was not happy with the manner in which the army crossed the Schuylkill into Chester County. “We lost here much time, by reason of men’s stripping off their stockings and shoes, and some of them their breeches,” complained Washington’s aide. “It was a pleasant day, and, had the men marched directly over by platoons without stripping, no harm could have ensued, their cloaths would have dried by night on their march, and the bottom would not have hurt their feet. The officers, too, discovered a delicacy quite unbecoming soldiers; quitting their platoons, & some getting horses of their acquaintances to ride over, and others getting over in a canoe. They would have better done their duty had they kept to their platoons and led in their men.” The delay, believed Pickering, potentially imperiled the army.40

Washington was not ready for another battle, but Anthony Wayne certainly was. The ever-combative commander worried that Howe’s army would recover from the blow it had suffered at the Brandywine because Washington was leaving him to lick his wounds rather than inflicting new ones. To Thomas Mifflin, the army’s quartermaster general, Wayne argued that Howe might “steal a March and pass the fords in the Vicinity of the Falls, unless we Immediately March down and Give them Battle.” In search of a satisfactory answer, Wayne figuratively urged Howe, “[C]ome then and push the Matter and take your fate.”41

In an effort to better defend Philadelphia, Washington ordered the Middle Bridge removed and sent French engineer Col. Louis Le Begue de Presle du Portail to Gen. Armstrong of the Pennsylvania militia with orders to fortify Swedes’ Ford with a redoubt and heavy cannon. “As it is not expected that these Works will have occasion to stand a long defence,” explained Washington, “they should be as such as can with the least labour & in the shortest time be completed, only that part of them which is opposed to cannon, need be of any considerable thickness & the whole of them should be rather calculated for Dispatch than any unnecessary Decorations or Regularity which Engineers are frequently too fond of.” The redoubt eventually constructed was the only earthwork built west of Philadelphia for defense.42

Desperate for reinforcements, the American commander ordered Alexander McDougall’s Connecticut brigade down from the Hudson Highlands. William Smallwood was with the Maryland militia at Oxford Meeting in southern Chester County, which meant he had 1,400 half-armed poorly trained men with no artillery, little ammunition, and almost no supplies. Although Smallwood’s men were in Howe’s rear, they were unreliable and would be of little use. “The Condition of my Troops, their Number, the State of their Arms, Discipline and Military Stores,” Smallwood wrote Washington, “I am Apprehensive will not enable me to render that essential Service.” Howe may “detach a Body of Infantry with their light Horse to Attack and disperse the Militia…. Your Excelly. is too well acquainted with Militia to place much Dependence in them when opposed to regular and veteran Troops, without Regular Forces to support them.” Harassing the British, one of Washington’s favorite tactics, was simply beyond the capabilities of the Maryland militia.43

The American army suffered another blow on September 14 when Congress voted to recall General Sullivan pending an inquiry into his actions on Staten Island and Brandywine. French General de Borre resigned that same day. Washington’s entreaties delayed Sullivan’s recall. “Our Situation at this time is critical and delicate,” he pleaded with the politicians. “[T]o derange the Army by withdrawing so many General Officers from it, may and must be attended with many disagreeable, if not ruinous, Consequences.” Washington’s optimism returned when he penned a letter to General Heath that same day: “Our troops have not lost their spirits, and I am in hopes we shall soon have an opportunity of compensating for the disaster we have sustained.”44

While Washington was attempting to keep his generals together and defend Philadelphia, Hessian troops under Col. Johann von Loos, which included the combined Hessian battalion, escorted the sick and wounded from the Brandywine to Wilmington. The shuffling column included 350 American prisoners. According to James Parker, they “consisted of 134 Irish immigrants, 65 English immigrants, 16 German immigrants, 9 Scots, 3 Italians, 1 Swiss, 1 Russian, 1 Gernsey, 3 French, and 82 ‘Americans.’”45

On September 15, Washington moved his army down the Lancaster Road another 12 miles (to what is today modern Malvern and Frazer). Washington made his headquarters in the Malin House at the intersection of the Swedes Ford Road and Lancaster Road. Advance parties of the army were situated three miles farther west in the vicinity of the White Horse Tavern (modern Malvern). With its rear stretching back to the General Paoli Tavern in Tredyffrin Township, the army extended along more than three miles of the Lancaster Road. With this move, Washington was now in a position to block an enemy advance toward the Schuylkill in the Great Valley. This new location, however, did not protect Philadelphia along the Delaware River. Captain Alexander of the Continental frigate Delaware, anchored off Billingsport, believed 100 men could capture the place, which highlighted the river’s continued vulnerability to British warships. Washington, however, thought otherwise. He wanted to improve the defenses along the Delaware, but believed that “if we should be able to oppose Genl Howe with success in the Feild, the Works will be unnecessary.”46

That same evening of September 15, Howe issued orders that would send his army marching the next morning into the Great Valley. The next day, Cornwallis would leave the vicinity of Chester for a rendezvous with the main army while the Hessian von Mirbach battalion moved to Wilmington. Cornwallis marched up the Edgemont Road to Goshen Meeting to rejoin Howe, who then proceeded in the direction of the White Horse Tavern. That same morning, Washington’s men began marching down the Lancaster Road to ascend the South Valley Hill and block Howe from the Schuylkill River.47

Once again the two armies were on a collision course, and only five days after what would be the largest battle of the Revolutionary War. The Brandywine campaign had ended. The final phase of the 1777 campaign to seize the American capital of Philadelphia was underway.