For Robert Hegel

AUTHOR AND TEXTS

The Daodejing  (Classic of the Way and Virtue [hereafter cited as DDJ]) is traditionally attributed to Lao Dan, a slightly older contemporary of the historical Confucius (551–479 B.C.). Preponderant Chinese scholarship of the twentieth century (with notable exceptions found in Hu Shi

(Classic of the Way and Virtue [hereafter cited as DDJ]) is traditionally attributed to Lao Dan, a slightly older contemporary of the historical Confucius (551–479 B.C.). Preponderant Chinese scholarship of the twentieth century (with notable exceptions found in Hu Shi  and Xu Fuguan [Hsü Fu-kuan]

and Xu Fuguan [Hsü Fu-kuan]  )1 has both doubted and contested the attribution, and its cumulative skepticism across several decades has in turn influenced a great deal of modern scholarship on early Chinese thought,2 including even more recent examples.3 The most vigorous defense of the traditional position, marshaling counterarguments from a wide spectrum of current Chinese scholarship and archaeological findings, has been mounted by Chen Guying

)1 has both doubted and contested the attribution, and its cumulative skepticism across several decades has in turn influenced a great deal of modern scholarship on early Chinese thought,2 including even more recent examples.3 The most vigorous defense of the traditional position, marshaling counterarguments from a wide spectrum of current Chinese scholarship and archaeological findings, has been mounted by Chen Guying  , a professor of philosophy who has taught in both Taiwan and Beijing,4 but the controversy is by no means settled.

, a professor of philosophy who has taught in both Taiwan and Beijing,4 but the controversy is by no means settled.

Complicating the controversy of dating has been the discovery of new materials. The first major archaeological find crucial for our understanding of Laozi and a host of other related topics, issues, figures, and texts is, of course, the 1973 unearthing of the Mawangdui tomb materials located in what would be the region named Chu  , in present-day Changsha of Hunan province.5 The wealth and importance of the materials have been compared with those of the Dead Sea caves in the ancient Near East.6 Since their discovery, two versions of the DDJ on silk, copies in two different ancient Chinese scripts with some significant variations in diction, chapter order, and reversal of the two-part divisions of the received text, have been studied extensively by scholars worldwide. As one of the more recent translators has noted, however, “the Ma-wang-tui texts do not differ in any radical way from later versions of the text.”7 At least three translations of the Mawangdui texts are now available to the English reader.8

, in present-day Changsha of Hunan province.5 The wealth and importance of the materials have been compared with those of the Dead Sea caves in the ancient Near East.6 Since their discovery, two versions of the DDJ on silk, copies in two different ancient Chinese scripts with some significant variations in diction, chapter order, and reversal of the two-part divisions of the received text, have been studied extensively by scholars worldwide. As one of the more recent translators has noted, however, “the Ma-wang-tui texts do not differ in any radical way from later versions of the text.”7 At least three translations of the Mawangdui texts are now available to the English reader.8

The second and most recent (1993) discovery is also found in the land of Chu, located in Tomb Number 1 of the village Guodian  , at the town of Jingmen

, at the town of Jingmen  , Hubei province. Three copied versions of the DDJ are preserved on bamboo slips, now judged to be the oldest surviving texts of the classic because the date for them may possibly be set at “the end of the fourth century,”9 a date that would locate immediately the texts and the formation of the DDJ discourse as contemporaneous with Mencius (ca. 372–289 B.C.) or possibly much earlier. Preliminary examination indicates that the contents of the three versions (about two-fifths of the extant DDJ) are again largely similar to the received text, though the documents reveal different chapter arrangements and are not divided into two parts on the Way and Virtue, a staple feature of all known extant textual specimens up to this point.10 Participants of the International Conference at Dartmouth have debated the various conjectural hypotheses on the relationship of the Guodian’s manuscripts to the received text of Laozi—i.e., whether one derives from another, whether both represent diverse versions or textual stemmas, whether both represent different transcriptions from a common source, either written or oral, and what may be the relationship between these two text groups and the Mawangdui materials.11

, Hubei province. Three copied versions of the DDJ are preserved on bamboo slips, now judged to be the oldest surviving texts of the classic because the date for them may possibly be set at “the end of the fourth century,”9 a date that would locate immediately the texts and the formation of the DDJ discourse as contemporaneous with Mencius (ca. 372–289 B.C.) or possibly much earlier. Preliminary examination indicates that the contents of the three versions (about two-fifths of the extant DDJ) are again largely similar to the received text, though the documents reveal different chapter arrangements and are not divided into two parts on the Way and Virtue, a staple feature of all known extant textual specimens up to this point.10 Participants of the International Conference at Dartmouth have debated the various conjectural hypotheses on the relationship of the Guodian’s manuscripts to the received text of Laozi—i.e., whether one derives from another, whether both represent diverse versions or textual stemmas, whether both represent different transcriptions from a common source, either written or oral, and what may be the relationship between these two text groups and the Mawangdui materials.11

According to the brief but much later written biography of Sima Qian,12 Lao Dan was a native of Chu, a southerner from the perspective of ancient geography. His family name was given as Li  , name Er

, name Er  , and his style Dan

, and his style Dan  , the last graph glossed by the Han lexicon Shuowen

, the last graph glossed by the Han lexicon Shuowen  as meaning “ears extended

as meaning “ears extended  .” He was said to have served as the archivist of the Zhou royal court. Although the graph li itself has appeared already in such ancient documents as the Classic of Poetry, the Zuo Commentary, and Mencius, with the meaning of “plum tree” or its fruit,13 as a name, it has been considered by Chinese philologists since the Han to have evolved from the homophone li

.” He was said to have served as the archivist of the Zhou royal court. Although the graph li itself has appeared already in such ancient documents as the Classic of Poetry, the Zuo Commentary, and Mencius, with the meaning of “plum tree” or its fruit,13 as a name, it has been considered by Chinese philologists since the Han to have evolved from the homophone li  , meaning “village.”14 The Tongzhi

, meaning “village.”14 The Tongzhi  , compiled by Zheng Qiao

, compiled by Zheng Qiao  (1104–1162), on the basis of the alleged custom in antiquity to use one’s appointed office also as surname, offers an alternative explanation that Li derives from such other homophones as li

(1104–1162), on the basis of the alleged custom in antiquity to use one’s appointed office also as surname, offers an alternative explanation that Li derives from such other homophones as li  , meaning “messenger” or “envoy,” or li

, meaning “messenger” or “envoy,” or li  , meaning “jail warden.” Because li as village is frequently on loan for the word for envoy,15 which, in turn, was used by Sima Qian to account for the identity of the homophonous name Li Li

, meaning “jail warden.” Because li as village is frequently on loan for the word for envoy,15 which, in turn, was used by Sima Qian to account for the identity of the homophonous name Li Li  ,16 a definitive origin of the name Li may remain a philological puzzle.

,16 a definitive origin of the name Li may remain a philological puzzle.

Sima Qian’s biography, however, has aroused further scholarly controversy over name and identity, because his narrative, by mentioning a nameless person observing that “Lao Laizi is also a person of Chu

,” seems to suggest that his subject under discussion also might have gone by the name of Lao. Although the graph lao

,” seems to suggest that his subject under discussion also might have gone by the name of Lao. Although the graph lao  is indisputably used to designate a surname in such ancient texts as the Zuo Commentary (Duke Cheng 15; Duke Zhao 14) and the Analects (7. 1), Sima’s casual narration does not warrant confident reception. Most modern scholars agree that the word yi

is indisputably used to designate a surname in such ancient texts as the Zuo Commentary (Duke Cheng 15; Duke Zhao 14) and the Analects (7. 1), Sima’s casual narration does not warrant confident reception. Most modern scholars agree that the word yi  as used in the observation has the force of making Laozi and Lao Laizi two different persons. Finally, the biography cites a third observation by a nameless person that “[the Grand Scribe of Zhou] Dan is, in fact, Laozi [

as used in the observation has the force of making Laozi and Lao Laizi two different persons. Finally, the biography cites a third observation by a nameless person that “[the Grand Scribe of Zhou] Dan is, in fact, Laozi [ ],” but this ancient hypothesis has been hotly contested and largely refuted in modern scholarship.17 The incident of the Grand Scribe meeting with Lord Xian of Qin

],” but this ancient hypothesis has been hotly contested and largely refuted in modern scholarship.17 The incident of the Grand Scribe meeting with Lord Xian of Qin  alluded to in the biography is also recorded in such other parts of the Shiji as “The Basic Annals of the Zhou

alluded to in the biography is also recorded in such other parts of the Shiji as “The Basic Annals of the Zhou  ,” “The Basic Annals of the Qin

,” “The Basic Annals of the Qin  ,” and “The Document of the Fengshan Ritual

,” and “The Document of the Fengshan Ritual  ,” but none of those episodes has any reference to the identification of Dan as Laozi.

,” but none of those episodes has any reference to the identification of Dan as Laozi.

Sima’s tantalizing mode of presenting his subject’s identity may have followed, as one modern editor and translator of the DDJ suggests, the “rhetorical rectitude of the Spring and Autumn Annals: that one should use what is trustworthy to transmit what is trustworthy, and what is doubtful to transmit what is doubtful  .”18 But what is doubtful, thus represented, has certainly elicited more doubt not confined merely to the name of Laozi, and an opinion such as that of William Boltz’s, that the biography “contains virtually nothing that is demonstrably factual,”19 is widely shared today. That conviction notwithstanding, three assertions by Sima are noteworthy not only because they help to shape the entire textualized tradition of Laozi for posterity, but also because they continue to influence the contemporary scholarly reception of this tradition.

.”18 But what is doubtful, thus represented, has certainly elicited more doubt not confined merely to the name of Laozi, and an opinion such as that of William Boltz’s, that the biography “contains virtually nothing that is demonstrably factual,”19 is widely shared today. That conviction notwithstanding, three assertions by Sima are noteworthy not only because they help to shape the entire textualized tradition of Laozi for posterity, but also because they continue to influence the contemporary scholarly reception of this tradition.

The first of the assertions from the biography claims that Laozi had authored a book in two parts that, in 5,000–plus words, expounded the meaning of the Way and Virtue. The length of the work thus noted roughly matches that of the DDJ’s received text, while the summary of its content has not been challenged by the two most important textual discoveries of the twentieth century. The second remark pertains to the venerable tale of Confucius making inquiry of Laozi about ritual, or li  , a story that may have derived from a widespread legend of many meetings between the two eminent thinkers of antiquity, but the emphasis invariably falls on Confucius’s respect for and homage paid to the “Daoist” teacher.20 Of the at least sixteen episodes in the Zhuangzi that mention Laozi by name, for example, eight of them—all preserved in the “Outer Chapters” of the work—relate contacts or conversations of the latter with Confucius, and their discussions touch on “how to study the Way

, a story that may have derived from a widespread legend of many meetings between the two eminent thinkers of antiquity, but the emphasis invariably falls on Confucius’s respect for and homage paid to the “Daoist” teacher.20 Of the at least sixteen episodes in the Zhuangzi that mention Laozi by name, for example, eight of them—all preserved in the “Outer Chapters” of the work—relate contacts or conversations of the latter with Confucius, and their discussions touch on “how to study the Way  ” (Zhuangzi 12), on the Classic of Poetry, Classic of History, Classic of Change, Classic of Ritual (13), on ancient texts and the way of governance in relation to benevolence and rectitude (14), on cosmology (21), and on the nature of self-growth in all things (22). Sima Qian’s story of inquiry on ritual is given much more elaborate content and detail in the “Zengzi wen

” (Zhuangzi 12), on the Classic of Poetry, Classic of History, Classic of Change, Classic of Ritual (13), on ancient texts and the way of governance in relation to benevolence and rectitude (14), on cosmology (21), and on the nature of self-growth in all things (22). Sima Qian’s story of inquiry on ritual is given much more elaborate content and detail in the “Zengzi wen  ” (Master Zeng’s Queries) chapter of the Classic of Ritual. The Annals of Lü Buwei, moreover, remarks that “Confucius studied under Lao Dan” and with two other named but now unknown masters.21 Finally, the story of “Confucius meeting Laozi” is given pictorial form preserved on a slab of stone carvings found with the remains of the Wuliang Shrine and dated to the second century. Such a representation, according to a contemporary art historian, inspired a great many “iconographical studies” by mid- and late-Qing scholars eager to establish correspondence between the venerated classics of their literary sources and visual artifacts.22 As may be readily seen, this little tale of which thinker learned from whom, whether strictly historical or not, can attain enormous significance for one assessing the development of ancient Chinese thought. In a culture where priority and antecedent—and not just origin—inevitably posit also authority, whether Confucius took some ideas from Laozi matters a great deal.

” (Master Zeng’s Queries) chapter of the Classic of Ritual. The Annals of Lü Buwei, moreover, remarks that “Confucius studied under Lao Dan” and with two other named but now unknown masters.21 Finally, the story of “Confucius meeting Laozi” is given pictorial form preserved on a slab of stone carvings found with the remains of the Wuliang Shrine and dated to the second century. Such a representation, according to a contemporary art historian, inspired a great many “iconographical studies” by mid- and late-Qing scholars eager to establish correspondence between the venerated classics of their literary sources and visual artifacts.22 As may be readily seen, this little tale of which thinker learned from whom, whether strictly historical or not, can attain enormous significance for one assessing the development of ancient Chinese thought. In a culture where priority and antecedent—and not just origin—inevitably posit also authority, whether Confucius took some ideas from Laozi matters a great deal.

One aspect of how it matters, in fact, surfaces in the last and third assertion of Sima Qian, for his biography tellingly observes that “today, followers of Laozi denigrate Confucianism and students of Confucianism also denigrate Laozi.” Taken as a description of the relations between these two schools of thought descending from ancient China and already heir to protracted and intense rivalry by the Han, the historian’s words are nothing if not historical and factual. Indeed, they would acquire added truth and acuity across the centuries in highlighting such a clash of sentiments that has persisted down to the present. Not only are there charges and countercharges among modern savants in their findings, but their unacknowledged desire for the primacy of Confucius or Laozi as China’s first serious thinker would also color frequently their views on date, authorship, and textual meanings. Even for scholars who seemingly have little ideological stake in upholding the priority of either Confucianism or Daoism, their interpretations can vary on how one should construe a selfsame issue. Because the story of Confucius’s inquiry into rites with Laozi had been alluded to even in so manifestly a Confucian text as the Record of Ritual, the surmised reason for its inclusion divides modern readers. For Xu Fuguan, this legend had to be handed down from a tradition prior to the Han, one that had been so firmly entrenched that not even Han Confucians dared devise its removal. For A. C. Graham, on the other hand, the anecdote would appear more likely to be a Daoist invention to counter the growing influence of Confucianism during the Warring States period.23

RHETORIC

If the dating of the DDJ and the identity of its putative author or compiler(s) still await solution despite recent discoveries of new textual materials, the construal of textual meaning also continues to pose daunting challenges, as is evident in the scholarly discussions recorded in the Dartmouth Conference proceedings. In spite of its being one of the shortest classics of antiquity, its terse and subtle rhetoric, devoid of any mimesis of conversational discourse among named (and frequently known) figures of history—a staple feature in the vast majority of Warring States texts harking back to the Analects—has teased and tantalized readers down through the centuries. This and other features may contribute to explaining why the DDJ has been one of the most translated ancient texts of China in our time.

When compared with another text like the Zhuangzi, the DDJ displays a much more limited vocabulary and simpler diction, and its overall syntax seems less complicated than even that of a text like the Mencius. Upon every scrutiny, however, the DDJ appears to sport a deliberate predilection to exploit a well-known feature of classical Chinese: the grammatical fluidity, and thus ambiguity, of individual words. As all students of the language realize, a single graph in literary Sinitic, depending on the context, may be used as either a noun, a verb, an adjective, or even an adverb. How the reader construes its grammatical function will significantly modify its meaning. But, apart from this general linguistic character, why the DDJ continues to vex and perplex its every interpreter and translator must be the parlous and pervasive lack of infratextual context to ground one’s conjecture of grammatical functions and meanings. Bereft of any dialogical or narrative constraints manifest in so many of the texts that purport to record the gathered teachings of Warring States thinkers, the voice of the DDJ speaker at once asserts and teaches anyone and no one, a discourse without context or audience. The pithy, verselike meditations are unlike other known specimens of Chinese poetry of antiquity. Despite the noticeable use of rhyme and the tetrasyllabic line in many segments of the work, the textual content hardly engages any concrete specificities or visibilia of the natural (for example, the fauna and flora of the Classic of Poetry that so pleased Confucius) and human worlds. Among the early group of Warring States texts, the gnomic and sapiential texture of the DDJ is manifestly laced with the most abstract of diction. The occasional transposition of different sections in any one text—a problem that may have been caused by copyist “error,” redactor judgment, or the “misplacement” of writing materials like bamboo slips—and the seemingly casual insertion of connectives like “hence” or “therefore” augment the difficulty in gauging argumentative logic or coherence. To illustrate yet again some of these difficulties, the familiar sentences that open chapter 1 of part 1 of the received text (the chapter order of which will be presupposed throughout this brief essay)24 may serve as the convenient example beginning our discussion.

The pair of statements opening chapter 1 (dao ke dao, fei chang dao; ming ke ming, fei chang ming  ) seems as memorable as they are relatively uncomplicated. Virtually all readers past and present have understood the grammatical structure of the parallel assertions to be something like noun + auxiliary word + verb. A nagging question, nonetheless, involves how best to understand the second dao in each clause in such a way that will enable the three-word unit to form a cogent assertion. Translations into languages other than Chinese are also frequently tempted to indicate in some manner the sense and effect of the pun, but this attempt is complicated by the fact that already in the Analects, we can discern at least four senses in the usage of dao. The nominal one refers to a path or road (4.15; 5.6; 9.11) or an ethico-political principle operative within a person, community, or an institution (1.2, 11, 12; 3.16; 4.15; 5.2, 21; 7.4; 15.7, 29; 15.40; 16.2; 18.6; 19.12, 22, 25). The verbal one can be: “to guide or instruct” (1.5; 2.3; 12.23); “to say or speak” (14.28; 16.5).

) seems as memorable as they are relatively uncomplicated. Virtually all readers past and present have understood the grammatical structure of the parallel assertions to be something like noun + auxiliary word + verb. A nagging question, nonetheless, involves how best to understand the second dao in each clause in such a way that will enable the three-word unit to form a cogent assertion. Translations into languages other than Chinese are also frequently tempted to indicate in some manner the sense and effect of the pun, but this attempt is complicated by the fact that already in the Analects, we can discern at least four senses in the usage of dao. The nominal one refers to a path or road (4.15; 5.6; 9.11) or an ethico-political principle operative within a person, community, or an institution (1.2, 11, 12; 3.16; 4.15; 5.2, 21; 7.4; 15.7, 29; 15.40; 16.2; 18.6; 19.12, 22, 25). The verbal one can be: “to guide or instruct” (1.5; 2.3; 12.23); “to say or speak” (14.28; 16.5).

Most interpreters of the first dao seem to favor collapsing the two nominal usages into a related one: thus an abstract principle becomes metaphorically a way to be walked on or a path to be followed, a trope that finds increasing preference among recent English translations. For the second dao, the last option of the verbal meaning as saying or speaking has also been the preferred reading of most translations, in Western languages or the modern Chinese vernacular, especially in the light of such later comments by Zhuangzi: “The Way has never had borders, saying has never had norms…. The greatest Way cannot be cited, The greatest disputation cannot be spoken…. The Way lights up but does not guide…. Who knows an unspoken disputation, an untold Way?

.”25 A reading of the DDJ that comports with Zhuangzi and its own (chap. 2) equally provocative description of the sage as one who “undertakes teaching without words (xing bu yan zhi jiao

.”25 A reading of the DDJ that comports with Zhuangzi and its own (chap. 2) equally provocative description of the sage as one who “undertakes teaching without words (xing bu yan zhi jiao  ),” a phrase repeated in chapter 43, therefore, will emphasize “the untold Way” as the fitting changdao, or constant Way.

),” a phrase repeated in chapter 43, therefore, will emphasize “the untold Way” as the fitting changdao, or constant Way.

One clause in Zhuangzi’s very chapter on “The Sorting That Evens Things Out  ,” however, may insert a different, albeit not unrelated, nuance in the opening declaration of the DDJ. In observing that “the Way lights up but does not guide,” Zhuangzi may well be targeting for critique that understanding of dao as a form of normative, and thus superior, guidance for the people (min

,” however, may insert a different, albeit not unrelated, nuance in the opening declaration of the DDJ. In observing that “the Way lights up but does not guide,” Zhuangzi may well be targeting for critique that understanding of dao as a form of normative, and thus superior, guidance for the people (min  ) prescribed by the Confucian discourse (e.g., Analects 2.3: “Guide it with government [versus] guide it with virtue

) prescribed by the Confucian discourse (e.g., Analects 2.3: “Guide it with government [versus] guide it with virtue

”). Seen in this light, the DDJ’s first clause may mean something like “the Way that can instruct or guide is not the constant Way,” or to translate Zhuangzi’s phrase differently, only “the Way that does not guide (bu dao zhi dao)” is knowledge worth having.

”). Seen in this light, the DDJ’s first clause may mean something like “the Way that can instruct or guide is not the constant Way,” or to translate Zhuangzi’s phrase differently, only “the Way that does not guide (bu dao zhi dao)” is knowledge worth having.

Although differing in degree, both Laozi and Zhuangzi evidently share a stern estimate of language’s intrinsic limitations. This common skepticism, however, extends not merely to language per se, but much more so to linguistic discourse as a form of political and moral action such as that championed by Confucians and to its compatibility with the nondiscriminatory and noninterventionist mode of operation Laozi and Zhuangzi associate with the true and constant Dao. Read from the latter perspective, the first assertion of the DDJ is not necessarily one of apophatic mysticism, that somehow an ineffable or unspeakable Dao is to be preferred. What is constant (chang), rather, must be understood as that which is consonant with the virtues of the Dao articulated repeatedly in different segments of the text. If Confucius wishes to set forth a basis for proper government by fashioning or attempting to revive a normative system of names and referents (e.g., Analects 6.25 and 13.3 for “the rectification of names”; 12.11 for “government” as “let the ruler be a ruler”), the derived principles and inferences of which would be honored as authoritative paideia and encoded as canonical classics by later followers, the DDJ as a Daoist text would counter with a discourse that challenges both the need and adequacy of the discursive medium as self-authenticating nominalization and normative instruction.26 This difference on whether the Dao should be taken as a discourse of guidance has not been lost in subsequent centuries. Nearly two millennia later, Wang Shouren (Yangming)  (1472–1528), on the occasion of dedicating a refurbished library of a private school, began his commemorative essay with the ringing declaration for the enduring texts of his own tradition: “The Classics, they are the constant way

(1472–1528), on the occasion of dedicating a refurbished library of a private school, began his commemorative essay with the ringing declaration for the enduring texts of his own tradition: “The Classics, they are the constant way  .”27 For someone like Laozi, on the other hand, the “constant Name” is no more nameable, as we shall see, than ascribing to the constant Way a disposition for prescriptive guidance.

.”27 For someone like Laozi, on the other hand, the “constant Name” is no more nameable, as we shall see, than ascribing to the constant Way a disposition for prescriptive guidance.

After such an intriguing beginning, the DDJ text goes on to declare:

That-which-is-not names the beginning of heaven and earth

That-which-is names the mother of ten thousand things.

The subject of these two sentences, which I have deliberately rendered in this clumsy manner, refers, of course, to two of the most important dialectical concepts in the text: the wu  and the you

and the you  , which have the literal meanings of “there is not” and “there is,” although those meanings obtain in this particular instance only if the two graphs are taken to be nominals. If they are regarded as adjectives (and thus it obliges the concomitant switch of name [ming] from a verb to a noun), both the grammar and the semantics of the two statements may change significantly to the following:

, which have the literal meanings of “there is not” and “there is,” although those meanings obtain in this particular instance only if the two graphs are taken to be nominals. If they are regarded as adjectives (and thus it obliges the concomitant switch of name [ming] from a verb to a noun), both the grammar and the semantics of the two statements may change significantly to the following:

Without name [i.e., the nameless], the beginning of heaven and earth.

With name [i.e., the named], the mother of ten thousand things.

There is nothing in the received text’s Chinese construction, as far as I can determine, that would prevent either reading, but the force of the two assertions and their nuanced implications vary with the grammatical changes, much as the Keatsian “a thing of beauty is a joy forever” is not to be equated with the tepid “a beautiful thing.”

To both these sentences in the Mawangdui manuscripts, as A. C. Graham rightly observes,28 there is added a terminal particle (ye  ), in which case, the construction decisively prohibits making wu and you the nominal subjects. Instead, that feature turns the nameless (wu ming

), in which case, the construction decisively prohibits making wu and you the nominal subjects. Instead, that feature turns the nameless (wu ming  ) and the named (you ming

) and the named (you ming  ) into the proper ones. However, it must be pointed out as well that this particle is tagged on to all first six sentences of chapter 1 of the Mawangdui versions. The particle is a staple feature of definitions, explanations, and conclusions, and thus the way those texts punctuate, for this reader at least, conveys the tone and flavor of a particular editorial explanation. Despite a date earlier than the received text’s extant version, the Mawangdui texts may be no more authoritative than the later received text in providing us with the most “authentic” or compelling textual meaning. In this regard, it is unfortunate that the early chapters of the DDJ are not preserved in all three of the Guodian versions.

) into the proper ones. However, it must be pointed out as well that this particle is tagged on to all first six sentences of chapter 1 of the Mawangdui versions. The particle is a staple feature of definitions, explanations, and conclusions, and thus the way those texts punctuate, for this reader at least, conveys the tone and flavor of a particular editorial explanation. Despite a date earlier than the received text’s extant version, the Mawangdui texts may be no more authoritative than the later received text in providing us with the most “authentic” or compelling textual meaning. In this regard, it is unfortunate that the early chapters of the DDJ are not preserved in all three of the Guodian versions.

Wu and you in the DDJ and other classical Chinese texts have, of course, been translated frequently as “nothing” or “nonbeing” and “something” or “being.”29 Apart from the problem of whether to use the language of ontology in exegesis and translation,30 the inherent grammatical instability of the terms themselves imposes further difficulty when they are joined with other words in constructions susceptible to different readings. A revealing example may be found in what follows immediately in the text of chapter 1:

Therefore

frequent no/nothing desire/intend by means of observe its wonder

frequent is/something desire/intend by means of observe its bound

Once more, the crucial problem of interpretation in these lines boils down to whether the dialectical pair of wu and you ought to be taken as nominals or adjectives, for that decision will, in turn, affect one’s understanding of the sentential syntax, of how the string of graphs may be divided into meaningful units (i.e., duan ju  ). If the words are taken as adjectives, then they must be regarded as qualifiers of the word yu

). If the words are taken as adjectives, then they must be regarded as qualifiers of the word yu  , now understood in the nominal sense of “desire.” All five of the recent English translations (Lau, Mair, Hendricks, Ivanhoe, Roberts) have opted for this solution made explicit by the syntactical variation of the Mawangdui texts, but such a reading, I must point out, fails to persuade completely on two counts.

, now understood in the nominal sense of “desire.” All five of the recent English translations (Lau, Mair, Hendricks, Ivanhoe, Roberts) have opted for this solution made explicit by the syntactical variation of the Mawangdui texts, but such a reading, I must point out, fails to persuade completely on two counts.

First, the reading does not provide us with even a hint as to why the text should want to bring up the issue of desire and its lack thereof so abruptly at this point as a requisite for its cosmic observer. True enough, by chapter 3, the speaker is already using the phrase “wu yu  ,” but this is perfectly understandable even in a confined segmental context in which the discourse concentrates on how the sage’s action would affect the people. In chapter 1, on the other hand, we have no such indication. Why do we need desire to observe the wonders or subtleties (miao) of something, and why do we need to be rid of desire to observe the very limit of something (jiao, literally, boundary or border)? Moreover, although the DDJ certainly teaches the importance of not having desires, the opposite emphasis of “having desires

,” but this is perfectly understandable even in a confined segmental context in which the discourse concentrates on how the sage’s action would affect the people. In chapter 1, on the other hand, we have no such indication. Why do we need desire to observe the wonders or subtleties (miao) of something, and why do we need to be rid of desire to observe the very limit of something (jiao, literally, boundary or border)? Moreover, although the DDJ certainly teaches the importance of not having desires, the opposite emphasis of “having desires  ” is hardly conceivable in the light of such explicit statements elsewhere in the same document: “Watch the colorless and embrace the simple, diminish private longings and reduce desires

” is hardly conceivable in the light of such explicit statements elsewhere in the same document: “Watch the colorless and embrace the simple, diminish private longings and reduce desires

” (chap. 19); “I have no desires and the people themselves become simple

” (chap. 19); “I have no desires and the people themselves become simple  ” (chap. 57). Second, this reading emphasizing desires fails to pin down the exact force of the possessive deictic qi

” (chap. 57). Second, this reading emphasizing desires fails to pin down the exact force of the possessive deictic qi  (its), because it cannot locate its attributive referent. What is the object possessive of wonders/subtleties and boundary for which the text urges observation? Neither the reading of the Mawangdui texts nor the translations based on them seem to offer satisfactory answers to such questions.

(its), because it cannot locate its attributive referent. What is the object possessive of wonders/subtleties and boundary for which the text urges observation? Neither the reading of the Mawangdui texts nor the translations based on them seem to offer satisfactory answers to such questions.

If, however, we take wu and you as nouns, a reading consistent with their possible grammatical function already surfacing in the previous sentences of the chapter, the difficulty dissolves. The sense of the assertions would be:

Therefore, frequent [in the sense of hold on to or stay with] that-which-is-not, with the intent by means of which to observe its wonders; frequent that-which-is, with the intent by means of which to observe its boundary.

We may notice in this connection that the word chang  (frequent, constant) has been regarded by Qing philologists as a loan word for shang

(frequent, constant) has been regarded by Qing philologists as a loan word for shang  (to uphold, honor, esteem, respect) in classical texts like the Classic of Poetry and the Guanzi,31 an understanding further supported by historical phonology because both words were thought to be vocalized as ziang.32 If this move is adopted, the reading’s cogency would be strengthened further, for the sentence would read something like: “Uphold that-which-is-not, with the intent by means of which” etc.

(to uphold, honor, esteem, respect) in classical texts like the Classic of Poetry and the Guanzi,31 an understanding further supported by historical phonology because both words were thought to be vocalized as ziang.32 If this move is adopted, the reading’s cogency would be strengthened further, for the sentence would read something like: “Uphold that-which-is-not, with the intent by means of which” etc.

The reasonableness of such an interpretation is fourfold. First, it avoids the tendency, perhaps unintended, of so many translations in turning the sentences of each chapter into unrelated, individual utterances. Scrutiny of the Chinese text ought to persuade any attentive reader that the text’s playful and perplexing rhetoric is not achieved at the expense of coherent thought and argument altogether, virtues that the reading proposed here seeks to honor. Because the previous pair of sentences already asserts that wu and you perform a naming function of different aspects of the cosmos, the next pair adduces an argument of consequence—therefore (gu) do such and such. Second, the action proposed by this reading has nothing to do with desires or their lack thereof in the observer. The textual injunction is for the addressee to have constant regard for “nothing” and “something” so as to observe its wondrous manifestations and its reach or extent. The implied meaning of the word yu  in such a reading is purposive.

in such a reading is purposive.

Third, this reading brings out more distinctly the difference of what is to be observed with respect to you and wu, which justifies the use of the argumentative adverb gu (therefore). Having asserted that these two terms name “the beginning of heaven and earth” and “the mother of ten thousand things,” the text says, “therefore,” if you stay constantly with x or y, you will be able to observe the proper effects of x and y. The effects, however, are not the same, and, therefore, the observable takes on a different character expressed through the naunced diction of contrastive parallelism. If that-which-is-not or nothing (wu) names the beginning of heaven and earth, this is, in effect, another way of asserting (with chap. 40) that “something [you] is begotten of nothing  .” The commonsense speculation on cosmogony in the West may perhaps best be summed up in Lear’s words of Shakespeare’s play: “Nothing will come of nothing” (1.1.90). Only the deity in Judaism, Christianity, and Islam is capable of creatio ex nihilo, or making something out of nothing. Although the creative artist in later periods of the Western tradition is affirmed to have a capability that mimics the creative act of God, an affirmation interestingly echoed in the Chinese aphorism on falsehood and fiction no doubt derived from the DDJ—“Of nothing was born something” (wu zhong sheng you

.” The commonsense speculation on cosmogony in the West may perhaps best be summed up in Lear’s words of Shakespeare’s play: “Nothing will come of nothing” (1.1.90). Only the deity in Judaism, Christianity, and Islam is capable of creatio ex nihilo, or making something out of nothing. Although the creative artist in later periods of the Western tradition is affirmed to have a capability that mimics the creative act of God, an affirmation interestingly echoed in the Chinese aphorism on falsehood and fiction no doubt derived from the DDJ—“Of nothing was born something” (wu zhong sheng you  )—Laozi’s use of the word miao (mystery, marvel) here in chapter 1 aptly depicts the character of self-contradictory genesis. The action of how something is born of nothing defies explanation. On the other hand, once something (you) is posited as “the mother of ten thousand things,” the result of this procreative process involves replication and multiplication. Hence what is to be observed is the jiao, the range and reach, the border or limit, of ever-expanding phenomena.

)—Laozi’s use of the word miao (mystery, marvel) here in chapter 1 aptly depicts the character of self-contradictory genesis. The action of how something is born of nothing defies explanation. On the other hand, once something (you) is posited as “the mother of ten thousand things,” the result of this procreative process involves replication and multiplication. Hence what is to be observed is the jiao, the range and reach, the border or limit, of ever-expanding phenomena.

Fourth and finally, this reading thus satisfies the grammatical and syntactical demands of the text by making wu and you the proper attributive referents of qi (its) within the structure of the self-same sentence. What wonders and boundary are we supposed to observe? They are none other than the very conditions or characteristics of that-which-is-not and that-which-is, of “nonbeing” and “being.” As the text goes on to specify one further linkage in the discussion, “These two things [i.e., wu and you] emerge similarly [i.e., from the same source of the Dao?] but they are named differently  .”

.”

In closing this section, I would like to point out finally that in an eighth-century Dunhuang text, the Upper Scroll of Laozi’s Scripture of the Way  , a further variant can be found for the two sentences under consideration.33 What is noteworthy in this manuscript version is that the two uses of the co-verb yi

, a further variant can be found for the two sentences under consideration.33 What is noteworthy in this manuscript version is that the two uses of the co-verb yi  are completely removed by either the editor or the copyist,34 such that the sentences read:

are completely removed by either the editor or the copyist,34 such that the sentences read:  .” Apart from the alteration of diction at the end so that a different jiao (brightness) provides the object of vision, what is significant in this construction is that the graph yu makes much better sense as an auxiliary verb—“so as to, in order to”—than as a noun meaning “desire.” If this view—no less than the lines themselves—is accepted, the syntactical pause will almost certainly have to come after wu and you, thereby effectively eliminating any reference to desire from the couplet. As in the case of all textual interpretation and translation, reading the DDJ makes it apparent that philology at the level of individual words attains its true worth only if it serves the cause of hermeneutics, because textual understanding occurs largely at the level of sentences or meaningful semantic units (ju).

.” Apart from the alteration of diction at the end so that a different jiao (brightness) provides the object of vision, what is significant in this construction is that the graph yu makes much better sense as an auxiliary verb—“so as to, in order to”—than as a noun meaning “desire.” If this view—no less than the lines themselves—is accepted, the syntactical pause will almost certainly have to come after wu and you, thereby effectively eliminating any reference to desire from the couplet. As in the case of all textual interpretation and translation, reading the DDJ makes it apparent that philology at the level of individual words attains its true worth only if it serves the cause of hermeneutics, because textual understanding occurs largely at the level of sentences or meaningful semantic units (ju).

THEMATICS

The Dao

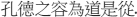

In the course of the received text, the graph for dao occurs at least seventy-three times, but as in the case of some of the words discussed in the previous section, the meaning of the graph varies significantly in different contexts. And, as has already been observed, the familiar couplet opening chapter 1 readily displays the speaker’s rhetorical cunning in the use of punning or paronomasia to define the enigmatic cosmic principle called the Dao. Moreover, as I have argued at length, the pun of the first line can be understood in at least two ways, whereas the pun of the second line is most likely to be understood as “the name that can be named is not the constant name.” Because the dao and ming are nothing if not two of the most debated terms in the schools of thought emerging in the early Warring States period, the polemical overtones immediately audible may well have come from targeting a rival position like the Confucian doctrine of the rectification of names (zheng ming  ). If the Master in the Analects 6.23 wants to pin down even a wine vessel with its “proper” appellation (gu

). If the Master in the Analects 6.23 wants to pin down even a wine vessel with its “proper” appellation (gu  ), and if his later disciple Xunzi contends that wise men “instituted names to refer to objects

), and if his later disciple Xunzi contends that wise men “instituted names to refer to objects  ,”35 the speaker in the DDJ is far less certain about either the accuracy of linguistic names or the identity of the object of his speech. Nonetheless, he offers an arresting depiction: “There is a thing comminglingly formed, / Born before heaven and earth. / Silent and solitary, / Standing alone without altering, / Going around without tiring, / It can be the mother of the world.” The denomination he assigns to this “thing” (wu

,”35 the speaker in the DDJ is far less certain about either the accuracy of linguistic names or the identity of the object of his speech. Nonetheless, he offers an arresting depiction: “There is a thing comminglingly formed, / Born before heaven and earth. / Silent and solitary, / Standing alone without altering, / Going around without tiring, / It can be the mother of the world.” The denomination he assigns to this “thing” (wu  ), however, is entirely arbitrary: “I, not knowing its name, / style it as Dao; reluctantly I give it the name of Great” (chap. 25).

), however, is entirely arbitrary: “I, not knowing its name, / style it as Dao; reluctantly I give it the name of Great” (chap. 25).

In sharp contrast to the Confucian teaching on names, the Dao in such a view exists linguistically as an uncertain signifier. In the thought of the DDJ, the Dao is referentially elusive, for it points neither to any palpably physical or material object nor to a fixed mental concept. Despite its being designated as a “thing,” according to chapter 21, the Dao is “shadowy and indistinct”  both in itself and in its image. Because of its invisibility, inaudibility, and intangibility, the speaker heaps on it such descriptions as “evanescent

both in itself and in its image. Because of its invisibility, inaudibility, and intangibility, the speaker heaps on it such descriptions as “evanescent  ,” “rarefied

,” “rarefied  ,” and “minute

,” and “minute  .” Although “these three cannot be fathomed, they commingle to become one,” existing in such oxymorons as “the shapeless shape, the thingless image

.” Although “these three cannot be fathomed, they commingle to become one,” existing in such oxymorons as “the shapeless shape, the thingless image  ” (chap. 14). Verbal ironies of this sort in both Laozi and Zhuangzi have in recent years tempted scholars to interpret them as virtually “protodeconstructionist” thinkers, a view this reader does not entirely endorse. Their reservations about language notwithstanding, neither of the Daoists seems to me to entertain a thoroughgoing skepticism in regard to the linguistic sign’s stability or capacity to signify, however limitedly. Rather, how these two thinkers use language is arguably the way a poet in many traditions uses language: keenly aware of the fugitive and feeble ephemerality of his or her medium, the poet nonetheless exploits it to the utmost to convey what seems impossible to communicate. Like the epic narration striving to make “darkness visible” in Milton’s Paradise Lost (1.63), Laozi’s metaphors seem intent on rendering absence presentable.

” (chap. 14). Verbal ironies of this sort in both Laozi and Zhuangzi have in recent years tempted scholars to interpret them as virtually “protodeconstructionist” thinkers, a view this reader does not entirely endorse. Their reservations about language notwithstanding, neither of the Daoists seems to me to entertain a thoroughgoing skepticism in regard to the linguistic sign’s stability or capacity to signify, however limitedly. Rather, how these two thinkers use language is arguably the way a poet in many traditions uses language: keenly aware of the fugitive and feeble ephemerality of his or her medium, the poet nonetheless exploits it to the utmost to convey what seems impossible to communicate. Like the epic narration striving to make “darkness visible” in Milton’s Paradise Lost (1.63), Laozi’s metaphors seem intent on rendering absence presentable.

Haphazard as this process may seem in constructing a “foundational” concept for his thought, the DDJ speaker is not at all shy in detailing all sorts of features and activities of the Dao. Because “the ten thousand things of the world are born from that-which-is, but that-which-is is born from that-which-is-not” (chap. 40), wu and you thus both constitute the “nature” of the Dao. Appositely, therefore, it is the “Dao [in the creative process] that begets one, one begets two, two begets three, and three begets ten thousand things” (chap. 42). In attributing (chap. 51) a cosmic procreative and nurturing role for the Dao and Virtue (de), the DDJ echoes the punning definition in the Zhuangzi: “That by which things obtain [de] life is called Virtue [de]  .”36 This understanding of the Dao as a force and principle of nature poses one most pointed contrast to the Confucian view. In the Analects, the word “Dao” also appears some seventy-seven times, but its meaning lies entirely in its sociopolitical significance and not in its generative agency, as may be seen from such following remarks:

.”36 This understanding of the Dao as a force and principle of nature poses one most pointed contrast to the Confucian view. In the Analects, the word “Dao” also appears some seventy-seven times, but its meaning lies entirely in its sociopolitical significance and not in its generative agency, as may be seen from such following remarks:

The superior man … swift in action but cautious in speech, would follow those possessive of the Way and become upright (1.14).

Of the Way of the former kings, this [i.e., the alleged “harmony” wrought by rites] is the most beautiful (1.12).

The superior man works at his foundation; when his foundation is set up and the Way is born. Being filial and obedient as a brother, is not this the foundation of a man’s character (1.2)?

Those who are called great ministers would serve their ruler with the Way, but when that’s not possible they would desist (11.24).

Unlike this sort of emphasis rehearsed by Confucius and his disciples, the DDJ asserts that if man, heaven, and earth all model themselves after the Dao, what the Dao models itself after is the self-so (ziran  ) frequently translated as nature (chap. 25). The semblance between the Dao and nature is what motivates the ten thousand things “to honor the Way and esteem Virtue

) frequently translated as nature (chap. 25). The semblance between the Dao and nature is what motivates the ten thousand things “to honor the Way and esteem Virtue  ,” but this sense of deference differs from the Confucian imperative because, “not decreed by authority, it is made constant in nature

,” but this sense of deference differs from the Confucian imperative because, “not decreed by authority, it is made constant in nature  ” (chap. 51). As this crucial segment of the DDJ goes on to make clear, the character of such life-giving and nurture bestowed by nature’s Dao is its very “selflessness”: “It gives life but claims no ownership; / It acts without causing dependency; / It promotes growth without governance; / This is called Mysterious Virtue.”

” (chap. 51). As this crucial segment of the DDJ goes on to make clear, the character of such life-giving and nurture bestowed by nature’s Dao is its very “selflessness”: “It gives life but claims no ownership; / It acts without causing dependency; / It promotes growth without governance; / This is called Mysterious Virtue.”

Namelessness in such a view implies the correlative rejection of a sense of self or identity. “The Dao is made constant in being nameless, or, the Dao [abides] constantly in the nameless  ” (chap. 32), declares the text, and again, “The Dao lies hidden in the nameless

” (chap. 32), declares the text, and again, “The Dao lies hidden in the nameless  ; / thus only the Dao is good at lending and bringing things to completion” (chap. 41). Such a posture in turn makes for profound implications for both ethics and psychology:

; / thus only the Dao is good at lending and bringing things to completion” (chap. 41). Such a posture in turn makes for profound implications for both ethics and psychology:

Thus the sage embraces the One to become the world’s mode:

He has no view of his own, and therefore he understands;

He does not affirm himself, and therefore he is known;

He does not commend himself, and therefore he is meritorious;

He does not boast, and therefore he endures.

He alone is not contentious, and therefore the world can never contend with him.

(CHAP. 22)

Whereas Zeng Shen  , one of Confucius’s chief disciples, frets about scrutinizing his body/self thrice daily

, one of Confucius’s chief disciples, frets about scrutinizing his body/self thrice daily  ) to determine his moral accomplishment (Analects 1.4), the DDJ offers a strikingly different model:

) to determine his moral accomplishment (Analects 1.4), the DDJ offers a strikingly different model:

The reason why heaven and earth are long lasting

Is that they do not give life to themselves.

Therefore, they can live long.

Thus the sage puts his body/self last,

And his body/self comes first;

Treats his body/self as extraneous,

And his body/self endures.

(CHAP. 7).

It is this very principle of “not ever regarding itself as great  ” that the Dao may be called great (chap. 25) and “able to bring to completion its own greatness

” that the Dao may be called great (chap. 25) and “able to bring to completion its own greatness  ” (chap. 34). Because the sage’s pacific and non-selfcentered disposition (chap. 24) is seen to be actually a source of immense power, the DDJ can declare that “the loftiest good is like water. / Water benefits ten thousand things without contention, / And it settles where most people despise. / Hence it comes nearest to the Way” (chap. 8).

” (chap. 34). Because the sage’s pacific and non-selfcentered disposition (chap. 24) is seen to be actually a source of immense power, the DDJ can declare that “the loftiest good is like water. / Water benefits ten thousand things without contention, / And it settles where most people despise. / Hence it comes nearest to the Way” (chap. 8).

The aquatic simile just cited, interestingly enough, reveals another significant difference between the DDJ and the rhetoric of a Confucian like Mencius, and the difference of linguistic construction indicates a deeper disparity in logic. For Mencius, the “natural” inclination of humans to pursue a benevolent ruler (1A.6) and practice the good (6A.2) is likened to water’s natural tendency. The passage in 6A.2, in fact, declares that “the matter of human nature being essentially good is like water always flowing downward  .”37 Notice that the Mencian argument proceeds from an assertion about the fundamental goodness of human nature assumed to be indisputable, and it then elicits for its support through analogy a phenomenon of nature. The analogy, of course, is debatable on two counts. On the premise itself, his fellow Confucian Xunzi a little later would offer the most pointed challenge to the affirmation of the goodness of human nature. As for the concluding comparison, the seemingly prescient acknowledgement of gravity can still be disputed when one remembers that primitive agricultural technology, already in use in Mencius’s time, can force water to flow “upward” or “sideways” in a particular arrangement or circumstance. The last point, in fact, was implicit in Gaozi’s remark about how human nature was like water that could through “outlet” be made to “flow east and west” at will, an observation that drew the Mencian attempted rebuttal.

.”37 Notice that the Mencian argument proceeds from an assertion about the fundamental goodness of human nature assumed to be indisputable, and it then elicits for its support through analogy a phenomenon of nature. The analogy, of course, is debatable on two counts. On the premise itself, his fellow Confucian Xunzi a little later would offer the most pointed challenge to the affirmation of the goodness of human nature. As for the concluding comparison, the seemingly prescient acknowledgement of gravity can still be disputed when one remembers that primitive agricultural technology, already in use in Mencius’s time, can force water to flow “upward” or “sideways” in a particular arrangement or circumstance. The last point, in fact, was implicit in Gaozi’s remark about how human nature was like water that could through “outlet” be made to “flow east and west” at will, an observation that drew the Mencian attempted rebuttal.

The DDJ’s argument, on the other hand, does not start with human nature; its text by contrast abounds with praise for what it considers to be water’s semblance to supreme goodness  . The defining “character” of water is precisely its manifest pliancy and weakness that no other thing under heaven can surpass

. The defining “character” of water is precisely its manifest pliancy and weakness that no other thing under heaven can surpass  (chap. 78), and this virtue further translates metaphorically into its pacificity or noncontentiousess (bu zheng

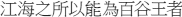

(chap. 78), and this virtue further translates metaphorically into its pacificity or noncontentiousess (bu zheng  ). In this view, from the observed phenomenon of how gravity affects the behavior of water (same acknowledgment as Mencius’s) emerges a different, but more compelling, ethical analogy: water’s willingness to take a lowly position, an excellent disposition that renders the river and the sea to become “king of the hundred valleys

). In this view, from the observed phenomenon of how gravity affects the behavior of water (same acknowledgment as Mencius’s) emerges a different, but more compelling, ethical analogy: water’s willingness to take a lowly position, an excellent disposition that renders the river and the sea to become “king of the hundred valleys  ” (chap. 66), provides the basis for the argument that “the extremely pliant in the world will ride rough shod [D. C. Lau’s translation] over the hardest in the world

” (chap. 66), provides the basis for the argument that “the extremely pliant in the world will ride rough shod [D. C. Lau’s translation] over the hardest in the world  ” (chap. 43). The physical attributes and propensity of water, thus distilled, provide the discursive model for the seeker of the Dao.

” (chap. 43). The physical attributes and propensity of water, thus distilled, provide the discursive model for the seeker of the Dao.

Reversion

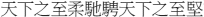

“Reversion is the Dao’s movement  ” (chap. 40), and this statement of the DDJ, already illustrated by the example of water just cited above, validates A. C. Graham’s conclusion that “the most characteristic gesture of Lao-tzu to overturn accepted descriptions is the reversal of priorities in chains of oppositions.”38 The gesture, in sum, represents an enlistment of what are perceived to be examples in natural phenomena to challenge directly certain cultural assumptions and ordering, the descriptions and priorities already valorized in human thought and society. If society tends to exalt “something,” “doing something,” “knowledge,” “male,” “big,” “strong,” “hard,” “straight,” and the like, the DDJ takes pains to foreground the opposites of “nothing,” “doing nothing,” “ignorance,” “female,” “small,” “weak,” “soft,” and “crooked.” The latter group of characteristics, however, represents more than mere oppositions, for they are ineluctably related to the former. One unavoidably implies the other because Laozi’s assumption is that such is the nature of the universe. Hence the text observes:

” (chap. 40), and this statement of the DDJ, already illustrated by the example of water just cited above, validates A. C. Graham’s conclusion that “the most characteristic gesture of Lao-tzu to overturn accepted descriptions is the reversal of priorities in chains of oppositions.”38 The gesture, in sum, represents an enlistment of what are perceived to be examples in natural phenomena to challenge directly certain cultural assumptions and ordering, the descriptions and priorities already valorized in human thought and society. If society tends to exalt “something,” “doing something,” “knowledge,” “male,” “big,” “strong,” “hard,” “straight,” and the like, the DDJ takes pains to foreground the opposites of “nothing,” “doing nothing,” “ignorance,” “female,” “small,” “weak,” “soft,” and “crooked.” The latter group of characteristics, however, represents more than mere oppositions, for they are ineluctably related to the former. One unavoidably implies the other because Laozi’s assumption is that such is the nature of the universe. Hence the text observes:

What is about to shrink

Will always stretch out;

What is about to weaken

Will always be strong;

What is about to become useless

Will always flourish;

What is to be taken

Will always give out.

This is called minute discernment [ ].

].

Although such an observation has been taken in both antiquity (e.g., Hanfeizi  , chap. 21, in juan 7, 11a [SBBY ed.]) and by subsequent commentators as the stratagem of realpolitik, the text itself may be arguing first for the dialectical phenomenon of how the fullest manifestation of one quality or condition must imply its diametrical opposite. Thus Laozi never tires to emphasize that “the bright way seems dull; / The progressive way seems regressive” (chap. 41). Again, “Great perfection seems incomplete, / But its use does not fail; / Great fullness seems drained, / But its use is inexhaustible” (chap. 45). The use of the word “seems” (ruo

, chap. 21, in juan 7, 11a [SBBY ed.]) and by subsequent commentators as the stratagem of realpolitik, the text itself may be arguing first for the dialectical phenomenon of how the fullest manifestation of one quality or condition must imply its diametrical opposite. Thus Laozi never tires to emphasize that “the bright way seems dull; / The progressive way seems regressive” (chap. 41). Again, “Great perfection seems incomplete, / But its use does not fail; / Great fullness seems drained, / But its use is inexhaustible” (chap. 45). The use of the word “seems” (ruo  ) in these declarations is noteworthy, for it suggests that neither natural phenomena nor cultural priorities are what they appear to be. To understand the “omen”40 and persistence of reversion requires, as the text says, “minute discernment” (wei ming). The hiddenness of the Dao and the paradox of appearance—“The great square has no corners; / The great vessel is late in making” (chap. 41); “Great skill seems clumsy; / Great eloquence seems tongue-tied” (chap. 45)—thus oblige the Daoist sage to be an astute hermeneutician. Not merely a transmitter, an editor, or an interpreter of texts, this sort of a sage must also possess the ability to read the subtle semiotics of nature and culture, to see what others do not see. It is for this reason as well that the sage himself also does not appear to be what he is, for his deportment and even his demeanor are utterly different from the rest of the people (chap. 20).

) in these declarations is noteworthy, for it suggests that neither natural phenomena nor cultural priorities are what they appear to be. To understand the “omen”40 and persistence of reversion requires, as the text says, “minute discernment” (wei ming). The hiddenness of the Dao and the paradox of appearance—“The great square has no corners; / The great vessel is late in making” (chap. 41); “Great skill seems clumsy; / Great eloquence seems tongue-tied” (chap. 45)—thus oblige the Daoist sage to be an astute hermeneutician. Not merely a transmitter, an editor, or an interpreter of texts, this sort of a sage must also possess the ability to read the subtle semiotics of nature and culture, to see what others do not see. It is for this reason as well that the sage himself also does not appear to be what he is, for his deportment and even his demeanor are utterly different from the rest of the people (chap. 20).

The meaning of reversion (fan), however, is not exhausted by opposition or opposite. As the idea is discussed in the DDJ, it acquires further development when it becomes associated with such notions as reversal and return (gui, fu). When attempting to describe the invisible, inaudible, and ungraspable Dao in chapter 14, the text goes on to say: “Its upper part does not dazzle; / its lower part is not opaque. / Unending, it cannot be named; / Once more it returns to no thing  .” The movement of the Dao thus operates in the mode of recursive cyclicity, because according to the logic here, that you which is begotten of wu (chap. 40) will also eventually go back to “nothing.” Hence the crucial and grand declaration of chapter 16:

.” The movement of the Dao thus operates in the mode of recursive cyclicity, because according to the logic here, that you which is begotten of wu (chap. 40) will also eventually go back to “nothing.” Hence the crucial and grand declaration of chapter 16:

The ten thousand things flourish together;

And I use them to observe reversal [ ].

].

The irony of the declaration here is generated precisely by the paradox that when everything seems to be alive and thriving, the sage speaker—and he alone—is the one who sees through that very phenomenon to adduce an opposite condition. Thus he continues:

Now, these things thrive in abundance,

But each again returns to its roots.

Return to roots is called stillness.

It is called the reversal to destiny.

Reversal to destiny is called constancy.

Knowing constancy is called discernment.

Not knowing constancy, one foolishly practices violence.

Knowing constancy induces forbearance;

Forbearance is impartial;

Impartiality is king;

Kingliness is heaven;

And Dao is perpetuity,

Free from danger till the end of life.

A knowledge of such a constant process wherein all things must reverse from a state of “something” to a condition of “nothing” induces a concomitant reordering of preferences and values. If age is valorized in Confucius’s autobiographical account of his moral accomplishment based on advancing decades of cultivation—“at seventy I followed my heart’s desires without overstepping the line” (Analects 2.4)—the DDJ, on the other hand, puts its recurrent emphasis on the condition of infancy or babyhood (chaps. 20, 28, 49, 55). The praise for the abundantly virtuous naked child who is immune to attacks by poisonous insects or ferocious animals, however, has little to do with secret revelation of Christian messianism read into the text by later Jesuit exegetes. Although both the terms (naked child [chizi  ], baby or infant [ying’er

], baby or infant [ying’er  ]) and the depiction of infancy had been appropriated by later Daoist adepts to represent the state of realized immortality in physiological alchemy, the DDJ text makes it apparent that what it cherishes in the infant is its characteristics of weakness (ruo

]) and the depiction of infancy had been appropriated by later Daoist adepts to represent the state of realized immortality in physiological alchemy, the DDJ text makes it apparent that what it cherishes in the infant is its characteristics of weakness (ruo  ), pacificity (he

), pacificity (he  ), and suppleness or pliancy (rou

), and suppleness or pliancy (rou  ). Because a living human is supple and only a dead one is stiff (chap. 76), the infant betokens the supreme embodiment of life. “Things that mature will become old, / And this is called Not-Dao. / Not-Dao will perish early” (chap. 55). Herein lies one intriguing but perhaps unintended irony of the DDJ: Laozi, or Master Old, so named by the legend that he was born with a head of white hair, is actually required by his teachings to exalt the youthful and the newborn.42

). Because a living human is supple and only a dead one is stiff (chap. 76), the infant betokens the supreme embodiment of life. “Things that mature will become old, / And this is called Not-Dao. / Not-Dao will perish early” (chap. 55). Herein lies one intriguing but perhaps unintended irony of the DDJ: Laozi, or Master Old, so named by the legend that he was born with a head of white hair, is actually required by his teachings to exalt the youthful and the newborn.42

Rulership

As has been intimated somewhat in the foregoing section already, the implications for ethics and psychology embedded in the DDJ betoken more than insights for personal self-cultivation. The text makes apparent that its concerns are deeply embedded in politics and the implicit critique of rival theories on society and government. Beginning with chapter 2 and going right to the end, the vocabulary of the DDJ alights repeatedly on such names as min  (people), zhi

(people), zhi  (governance, to rule), baixing

(governance, to rule), baixing  (literally, the names of a hundred clans, stock metaphor for the common folk), guo or guojia

(literally, the names of a hundred clans, stock metaphor for the common folk), guo or guojia  (state), tianxia

(state), tianxia  (under heaven, stock metaphor for the political domain as known world, a term that had been used sometimes to argue for dating the DDJ or some parts thereof to postimperial times), wang

(under heaven, stock metaphor for the political domain as known world, a term that had been used sometimes to argue for dating the DDJ or some parts thereof to postimperial times), wang  (king, kingly, kingliness, and to rule as king), chen

(king, kingly, kingliness, and to rule as king), chen  (political subject), bing

(political subject), bing  (soldiers, arms, troops, military affairs), shi

(soldiers, arms, troops, military affairs), shi  (troops), jun

(troops), jun  (troops, military units), and jun

(troops, military units), and jun  (sovereign, lord, ruler). They are all terms receiving recurrent explication and debate among Warring States thinkers, and it is in comparison with them that Laozi’s thought attains its pithy and piquant distinctiveness. Whereas the Confucians, the Mohists, and the later Legalists have all advocated theories of governance that rely on policies and examples issued from the top down, the DDJ speaker is forthright in rejecting much of the leadership role of the ruling classes and places the proper initiatives as squarely coming from the common people.43 Laozi’s program of reversal may readily be seen in chapter 77, where he seeks to overturn the locative metaphors of the high, or upper (shang

(sovereign, lord, ruler). They are all terms receiving recurrent explication and debate among Warring States thinkers, and it is in comparison with them that Laozi’s thought attains its pithy and piquant distinctiveness. Whereas the Confucians, the Mohists, and the later Legalists have all advocated theories of governance that rely on policies and examples issued from the top down, the DDJ speaker is forthright in rejecting much of the leadership role of the ruling classes and places the proper initiatives as squarely coming from the common people.43 Laozi’s program of reversal may readily be seen in chapter 77, where he seeks to overturn the locative metaphors of the high, or upper (shang  ), and the low (xia

), and the low (xia  ) by revaluation: “Is not the way of heaven like stretching a bow? / The high is pressed down; / The low is raised; / The excessive it hurts, / And the deficient it mends.” Exactly opposite such heavenly generosity is “the way of humans

) by revaluation: “Is not the way of heaven like stretching a bow? / The high is pressed down; / The low is raised; / The excessive it hurts, / And the deficient it mends.” Exactly opposite such heavenly generosity is “the way of humans  ” that “hurts the insufficient in order to serve the excessive

” that “hurts the insufficient in order to serve the excessive  .” The injuries perpetrated by humans are traced (chap. 75) specifically to heavy taxation, which causes popular starvation, to the ruling classes’ overcraving for life, which leads them to regard death lightly, and to their predilection for sheer intervention (you wei

.” The injuries perpetrated by humans are traced (chap. 75) specifically to heavy taxation, which causes popular starvation, to the ruling classes’ overcraving for life, which leads them to regard death lightly, and to their predilection for sheer intervention (you wei  ), which eventually makes the governance of people difficult (min zhi nan zhi

), which eventually makes the governance of people difficult (min zhi nan zhi  ). This critique of those in power, however, does not mean that Laozi is advocating necessarily an incipient form of republicanism, let alone democracy,44 for in his thinking, there is still the Daoist sage who, like the ideal “kingly one” (wang zhe

). This critique of those in power, however, does not mean that Laozi is advocating necessarily an incipient form of republicanism, let alone democracy,44 for in his thinking, there is still the Daoist sage who, like the ideal “kingly one” (wang zhe  ) championed by Mencius and Xunzi, is especially fit to govern because of certain qualities. For Laozi, “he who is possessive of the Dao” (you dao zhe

) championed by Mencius and Xunzi, is especially fit to govern because of certain qualities. For Laozi, “he who is possessive of the Dao” (you dao zhe  ) is the one who can “offer his surplus to the world” (chap. 77). That is why the text observes in another place that “the sage resides above but the people are not burdened; / He leads in front but the people are not harmed” (chap. 66).

) is the one who can “offer his surplus to the world” (chap. 77). That is why the text observes in another place that “the sage resides above but the people are not burdened; / He leads in front but the people are not harmed” (chap. 66).

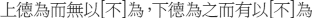

The DDJ’s focus on the needs and priorities of the common people thus complements the reversal of the sage-ruler’s role and values, while both themes derive apparently from the fundamental concept of the Dao and its relations with nature, or ziran. In this light we can understand not only the powerful critique that Laozi mounts against Confucian ethics and politics but also his ostensibly more extreme statements on the people. Familiar to students of classical Chinese thought, the Confucian emphasis on the personal rectitude of the ruler as virtue (de) is firmly and finally based on its suasive power to attract and mold his subjects (Analects 2.1; 12.19), causing his people to rush to his allegiance like water flowing downward (Mencius 1A.6). The constitution of that virtue, too, is well known: filial piety (xiao  ), and benevolence (ren

), and benevolence (ren  ) concretely defined as primarily the love of parents and kin,45 and the regard for established rituals and ceremonies (li

) concretely defined as primarily the love of parents and kin,45 and the regard for established rituals and ceremonies (li  ) amid both court and clan (Analects 1.12; 2.5, 23; 3.17, 22; 4.13; 13.4). Such a notion of virtue as a capacity not only to practice the good but also by that very practice to provoke a similar response from those benefiting from such an action may underlie the paronomasic definition of “virtue is that which acquires or obtains” (de zhe de ye

) amid both court and clan (Analects 1.12; 2.5, 23; 3.17, 22; 4.13; 13.4). Such a notion of virtue as a capacity not only to practice the good but also by that very practice to provoke a similar response from those benefiting from such an action may underlie the paronomasic definition of “virtue is that which acquires or obtains” (de zhe de ye  ). Analects 2.1 provides the classic proof text: “To govern by means of virtue may be compared with the Pole Star: it assumes its proper position [in the middle] and the various stars gather to pay homage.” These oft-quoted words of Confucius validate a modern scholar’s elucidation of the Confucian conception of de as a propensity to influence feeling and behavior, a “moral force” or potency that would elicit reciprocity.46

). Analects 2.1 provides the classic proof text: “To govern by means of virtue may be compared with the Pole Star: it assumes its proper position [in the middle] and the various stars gather to pay homage.” These oft-quoted words of Confucius validate a modern scholar’s elucidation of the Confucian conception of de as a propensity to influence feeling and behavior, a “moral force” or potency that would elicit reciprocity.46