That which is above physical form we call the way; that which is below physical form we call instrument. That which transforms and regulates [things] we call change. To deduce [such principles] and act on them we call connection. To take up [such principles] and install them among the people of the world we call service and enterprise.

—THE CLASSIC OF CHANGE, “COMMENTARY

ON THE APPENDED PHRASES,” 1.12

CONTINUITY AND CHANGE: A LINGUISTIC PARABLE

Whether there is such a thing as the “essence” or “soul” of China and whether it can change over time are hardly idle questions, questions that I’d like to examine on this occasion. Even for a single individual, the questions of the subject and personal identity-who am I and in what sense the I of today is the same as the I of yesterday-are questions of great complexity and much discussion.1 To note the difficulty inherent in my project does not mean that students of China have been reluctant to debate the peculiar or distinctive characteristics of that civilization. Indeed, throughout the long course of China’s existence, interested observers both past and present, both native and foreign, have not been hesitant in making pronouncements about that culture’s spirit and content-declarations that are most affirmative or most critical, wildly errant or astutely percipient. How to adjudicate between markedly conflicting visions or “sightings” (as Jonathan Spence calls them in his 1998 book The Chan’s Great Continent: China in Western Minds) regarding any reputedly defining feature of China is not only hazardous, but as is often the case, the decision must also turn on further debate and interpretation. “our understanding of Chineseness,” according to the wise suggestion of historian Wang Gungwu for some sort of guiding principle for the endeavor, “must recognize the following: it is living and changeable; it is also the product of a shared historical experience whose record has continually influenced its growth; it has become increasingly a self-conscious matter for China; and it should be related to what appears to be, or to have been Chinese in the eyes of the non-Chinese.”2

The history of Western sinology as a whole, in this light of Wang’s remark, can-and must-be understood as one long process of encounter wherein discovery has been constantly commingled with reaction and evaluation. From Marco Polo’s (ca. 1254–1324) rhapsodic report of old Cathay’s material riches and architectural opulence, the Enlightenment’s marvel at Confucian texts, philosophy, and bureaucracy, through early European exaltation of Chinese as possibly an “Edenic” language, Hegel’s denigration of Chinese history and Bertrand Russell’s (1872–1970) captious remarks about “effeminate and cowardly behavior,” to Charles de Gaulle (1890–1970), Richard Nixon (1913–1994), and Henry Kissinger’s (1923–) reports of their audiences with Mao Zedong (1893–1976), the encyclopedic charting and survey of science and technology in Chinese civilization by the late Joseph Needham and colleagues, and the equally voluminous and collaborative writing of The Cambridge History of China, the West of the last 500 years has sifted and scrutinized the Middle Kingdom relentlessly.3 Virtually all salient aspects of historical and modern Chinese culture-language, behavior, social organization and kinship structure, religion, politics, finance, population, books and printing, the healing arts (to name a few that come readily to mind)-have been studied with increasing sophistication and intensity. In the twentieth century more than ever, the passion for knowledge about China has been fueled by historical circumstances, political necessity, and the advance in technology. Such knowledge, however, has less an unchanging reality as its object than a historical experience that is constantly subject to modification by anticipated or unexpected forces of change.

Take, for example, the matter of the Chinese language, which, particularly in its scriptural form, may certainly be considered an enduring bequest of Chinese culture. Enjoying a virtually unparalleled history of longevity and continuous development over several thousand years, the language has exerted incalculable influence on every major aspect of Chinese civilization.4 “What was clearly Chinese [by the time of the first millennium before the common era] for the Chinese,” writes Wang Gungwu, “was their language of signs and symbols. It had overcome the limitations of speech and hearing and had united peoples who could not have understood each other otherwise.”5 What is enduring, however, is not synonymous with the unchanging, because the technological advance in the form of the personal computer during the last decade has wrought a revolution in the use and dissemination of Chinese that is wholly without precedent. The computer’s facilitation of reproducing the nonalphabet Chinese script has moved from laborious techniques of “translating” stroke-based constructions of Chinese graphs onto the alphabet-based keyboard, through breakthrough designs of graphic typesetting and storage coordinated with different systems of romanization (Wade-Giles and pinyin for Mandarin, and more recently, major Chinese dialects such as Cantonese, Hakka, and Taiwanese), to stylus or even voice-activated input for direct representation. As far as the keyboard is concerned, the massive utilization of a romanized system of representation has meant, first of all, another giant step in the globalization of the modern English alphabet, because the keyboard built on these twenty-six letters is now used by hundreds of millions of people, who themselves may know little or no English, to reproduce nonetheless effectively the Chinese script and, thus, to communicate in written Chinese.

For native and foreign users alike, the computer’s alphabetical keyboard has perhaps unintentionally abetted the language reform measures pioneered by the PRC (People’s Republic of China) when it first introduced the pinyin system. This schematization, which has been severely criticized and resisted (myself included), has suddenly been transformed into a virtually universal practice, for assisted by the computer, what it has succeeded in doing more than government policy is to provide an irresistible linkage between script and sound, through the enforced adoption of an alphabetical syllabary. For the first time in their long history, the users of the Chinese language are compelled to confront a phonological method of comprehending, retaining, and reproducing their language; that is, to match script to phonological representations that are completely conventionalized, hence standardized. In its function, the pinyin system is exactly the same as the Guoyu zhuyin fuhao  (phonetic symbols of the national language [Mandarin]), introduced in 1918. Whereas those symbols, however, are still constructed variations or simplified versions of Chinese graphs, the pinyin system is fashioned entirely by the English alphabet. This is the crucial difference. Although the alphabetization of Chinese phonemes by the PRC reformers was at first intended primarily for facilitating uniform vocalization and easy comprehension, the introduction of the computer changes the picture radically by joining this phonetic representation of the language to the effective reproduction of the script. Pinyin not merely grants immediate utility to the keyboard but it also directly assimilates into the language-and thus domesticates-symbolic elements once thought to be completely alien.6

(phonetic symbols of the national language [Mandarin]), introduced in 1918. Whereas those symbols, however, are still constructed variations or simplified versions of Chinese graphs, the pinyin system is fashioned entirely by the English alphabet. This is the crucial difference. Although the alphabetization of Chinese phonemes by the PRC reformers was at first intended primarily for facilitating uniform vocalization and easy comprehension, the introduction of the computer changes the picture radically by joining this phonetic representation of the language to the effective reproduction of the script. Pinyin not merely grants immediate utility to the keyboard but it also directly assimilates into the language-and thus domesticates-symbolic elements once thought to be completely alien.6

One not fully understood consequence of this development is precisely this necessity of thinking phonetically when using the computer. Whereas in the precomputer days a person writing in Chinese might well have reproduced a number of graphs on the page without knowing their precise or “correct” vocalization in the dominant vernacular, and this situation applies to even the clumsy Chinese typewriters, the current student taught to be reliant on the alphabet keyboard and a particular phonological system of representation in principle must master the proper phonemes that delimit the range of this individual’s working vocabulary. Wrong pronunciation or misvocalization while using a computer may mean complete stoppage of writing until the correct sound (i.e., correctly spelled phoneme) is ascertained. With this critical constraint, not only a tradition of several thousand years in acquiring, retaining, and reproducing a graphic-hence essentially imagistic (Fenollosa and Ezra Pound were both right and wrong!)-language has been drastically modified, but the very nature of that language itself may have been irreversibly altered. Since keyboard usage enforces strict reliance on mastery of a particular dialectal form of the language, the “limitations of speech and hearing”-Wang Gungwu’s phrase quoted earlier-are reimposed to a significant degree in the communicative process. On the other hand, the global familiarity of the English alphabet and the speed of the computer join to provide unprecedented rapidity in the use and dissemination of Chinese script.

Seen in this light, what the PRC began as a programmatic reform to help educate its vast population by opting to adopt pinyin, a syllabary constructed out of the English letters, is now immeasurably aided and made irreversible by the computer, for in its global use a resolutely nonalphabetical language has forever been alphabetized at least in its vocalized mode. Confronted by the recurring phenomenon on the computer that the phoneme ma may actually betoken eighteen graphs and as many or even more meanings, the student may be led by habit to valorize a sonic unit constructed in an alphabetical syllabary as a sort of stable, if not superior, semantic unit over against the individualized characters. In this way, the computer also ironically assists the other salient plank of the PRC’s linguistic reform platform, for the composition of the Chinese word (traditionally made up of both logographic and, frequently, phonographic elements) now becomes correspondingly less important. The PRC’s systematic proposal to simplify the graphic complexity of the characters and to promote, whenever context allows, the interchangeable use of homonyms is thus undeniably a logical extension of the decision to privilege sound and speaking over the writing system.7 Whether this kind of development must eventuate in the gross distortion and impoverishment of the Chinese language, as many critics once charged, and how it will affect the long-term preservation and modification of Chinese are questions not relevant to the present inquiry. Nevertheless one paradox-the changeability of the culturally permanent-has become certain, for language as part of the quintessentially Chinese, has, because of the computer, been touched and transformed by some element essentially foreign and alien. The non-Indo-European has become in part Indo-European.

Is this kind of development also possible in other domains of Chinese civilization, part of the Chinese “soul”? This is the question underlying the remaining portions of my essay, where I explore the perennially controversial issue of individual versus community or group in Chinese society and thought; the issue is focalized here as an examination of classical Confucianism and its compatibility with the modern advocacy of human rights. I have chosen to frame my inquiry along this line not merely because, as one scholar has put the matter, “the problem of human rights lies at the heart of modern political discourse.”8 Just as importantly, the discussion of the individual’s role and significance in Chinese culture inevitably encroaches on the central tenets of Confucian ethics and politics. For more than two millennia, the powerful and pervasive ideology sustaining imperial governance, kinship structures, social values, familial morality, and the formal educational system has been irrefutably Confucian. This cultural dominance has cast its long shadow even into contemporary China, as a passing journalistic remark today can still refer, justly, to Confucianism and Communism as that nation’s “sustaining (albeit collapsing) value systems.”9 Abroad the tradition continues its influence on diaspora Chinese communities the world over. Even more impressively, attempts in the rehabilitation and retrieval of the Confucian tradition, among certain educated elites enjoying also apparent support from state and local governments, have been steadily escalating in China itself during the post-Mao era that began in the seventies. Witness the series of conferences devoted to Confucius and his teachings that were held in Hangzhou, 1980, in Beijing, 1989 (an international symposium to celebrate the sage’s 2,540th birthday anniversary), and again in Beijing, 1994, during which gathering Singapore’s Lee Kuan Yew was the keynote speaker. On September 26, 1999, the celebration for the 2,550th birthday anniversary was held with great fanfare at Confucius’s birthplace, Qufu, Shandong province, and it coincided with the completion of the first phase of construction of a sizeable Research Institute of Confucius  .10 An exercise such as that here, therefore, cannot avoid querying the persistent relevance of this tradition for Chinese communities looking toward the next millennium.

.10 An exercise such as that here, therefore, cannot avoid querying the persistent relevance of this tradition for Chinese communities looking toward the next millennium.

THE WEIGHT OF ANCESTORS

In his thoughtful essay, significantly titled “Early Civilization in China: Reflections on How It Became Chinese,”11, historian David N. Keightley has enumerated many factors during the time of the Neolithic to the early imperial age that helped to answer his titular question. These include hierarchical social distinctions; massive mobilization of labor; an emphasis on ritual in all dimensions of life, including the early institutionalization of ancestor worship; an emphasis on formal boundaries and models; an ethic of service, obligation, and emulation; little sense of tragedy or irony; the lack of significant foreign invasions; and the absence of any pluralistic national traditions.12 Another distinctive aspect of early Chinese civilization, “an emphasis on the group rather than the individual,” finds striking illustration in Keightley’s comparison of a fifth-century kylix vase by the Penthesileia Painter with a hu wine vase dated to the Eastern Zhou period (late sixth to fifth centuries B.C.). Whereas the lone figures of Achilles and the Amazon queen occupy virtually the entire surface of the Greek vase, the decor of the Chinese vessel displays scenes of group activities-battles by land and sea, banquets, hunting, and the picking of mulberry leaves. Because these scenes are “stereotypical silhouettes” of nameless hordes, “the overwhelming impression conveyed by these tableaux is one of contemporaneous, regimented, mass activity.”13

This treatment of early Greek civilization by Keightley, to be sure, is vulnerable to criticism because he has concentrated exclusively on one depiction of archaic heroism and ignores completely both geometric pottery and the all-important implications of polis (city) and domos (house) present even in Homeric epics, not to mention later philosophers, dramatists, and historians. Whatever decorative motif that might have been preferred by early Greek pottery, a culture showing little concern for communitarian values, however defined, could hardly be expected to produce Plato’s Republic, Thucydides’s History of the Pelopennesian War, and Aristotle’s Politics.

On the other hand, Keightley’s observation about the prevalence of the group already manifest in early China seems to me to be keen and unerring. Once more, however, iconographic suggestiveness needs to be enhanced and particularized by verbal artifacts. From preserved material inscriptions of the Neolithic to the formal writings of the early Han, a culture that displays so voluminous a record and so large a vocabulary of ancestral gradation and ranking, lineage, and kinship structures must be, even on a prima facie basis, interested in the life in and of the group. Similarly, the documents on rituals all center on court, clan, and household duties and activities, and they hardly qualify as prescriptions for personal ethics or individual behavior.14 Ritual events inscribed on bronze vessels, ritual behavior attributed to a practitioner like Confucius (e.g., Analects 10), and ritual patterns codified in various classic texts (Zhou Li  , Yi Li

, Yi Li  , Liji

, Liji  ) are not writings intended to induce proper behavior based on sound knowledge and critical judgment of a single individual (note ’Ἐκαστος), the starting point of Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics (1094a26–1095a12). They provide, rather, the purpose and plan of action already selected, established, and judged as worthy of persons or various kinds of person, the meaning of whose very existence is at the same time unalterably defined by their social status. Just as it is unthinkable for the ordinary plebian to behave like a minister, for that would indicate inordinate insolence, so a father is considered perverse if he engages in actions deemed appropriate only for his children, a sure sign of moral weakness. It is the recognition of this feature of ancient Chinese society, in fact, that must presuppose any discussion of the relations of the individual to the group by Confucius and followers, a period that spans the sixth century to the common era.

) are not writings intended to induce proper behavior based on sound knowledge and critical judgment of a single individual (note ’Ἐκαστος), the starting point of Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics (1094a26–1095a12). They provide, rather, the purpose and plan of action already selected, established, and judged as worthy of persons or various kinds of person, the meaning of whose very existence is at the same time unalterably defined by their social status. Just as it is unthinkable for the ordinary plebian to behave like a minister, for that would indicate inordinate insolence, so a father is considered perverse if he engages in actions deemed appropriate only for his children, a sure sign of moral weakness. It is the recognition of this feature of ancient Chinese society, in fact, that must presuppose any discussion of the relations of the individual to the group by Confucius and followers, a period that spans the sixth century to the common era.

In a well-known passage when Duke Jing of the state of Qi asked the Master about government,

Confucius answered, “let the ruler be a ruler, the subject a subject, the father a father, the son a son.”

The Duke said, “Splendid! Truly, if the ruler be not a ruler, the subject not a subject, the father not a father, the son not a son, then even if there be grain, would I get to eat it.”15

The marvelous feature of this dialogue is its purposive opacity. Neither the sage nor his interlocutor feels obliged to explain what letting a subject be a subject means, although subsequent Confucian disciples and commentators show little hesitancy in spelling out what they would consider the proper implications of these terse, laconic exhortations. In the immediate context of the anecdote, however, both men seem to know exactly well beforehand the practical content implied in Confucius’s dicta no less than the serious consequences of the success or failure of action on the part of persons thus classified. The punch clause of the duke’s utterance is especially illuminating in this regard, for the force of his rhetorical question is premised on his belief (and by extension, his listener’s as well) that agricultural success (“if there be grain”) can guarantee neither biological gratification (a human like him must eat) nor entitled benefit (as ruler and father, he might expect filial sharing of food from sons or tributes of grain from subjects). Rather, the duke’s enjoyment of sustenance in the taxonomic ideal depends on each differentiated class of persons in the social order, including the duke himself, fulfilling the unspecified but understood moral obligations.

There should be no mistake, however, that the implied rank and status of the persons thus classified already express concretely a set of unequal relations. In the biological realm, the son within the context of his own household may eventually attain the rank and status of a father. In the political sphere, on the other hand, the subject, unless he happens to be one who eventually overthrows the ruler, will likely remain forever a subject. It is the asymmetry of such relations, later to be permanently codified by Confucian disciples into the so-called Five or even Ten Relations (wu lun  , shi lun

, shi lun  ), that makes the meaning of the individual person in traditional Chinese culture not easily reconcilable with the basic presuppositions informing the Western discourse on human and civil rights.

), that makes the meaning of the individual person in traditional Chinese culture not easily reconcilable with the basic presuppositions informing the Western discourse on human and civil rights.

If one were to pose at this juncture the question as to what is the most significant and representative feature of Chinese social thought that has endured through the centuries, my own reply would point to the intimate homology that countless writers and thinkers have drawn between the state (guo  ) and the family or clan (jia

) and the family or clan (jia  ). Furthermore, the single social practice that offers both compelling illustration and underpinning of such a homology is also one that has rendered Chinese culture extremely distinctive, if not entirely unique, in the long course of its history. Long antedating the time of Confucius, ancestor worship has found ample documentation in the Shang oracle bone inscriptions. This familiar cultural practice within the affairs of the Shang state played a “central, institutionalized role,” because, as Keightley has astutely observed, it “promoted the dead to higher levels of authority and impersonality with the passage of generations, encouraged the genesis of hierarchical, protobureaucratic conceptions and … enhanced the value of these conceptions as more secular forms of government replaced the Bronze Age theocracy.”16

). Furthermore, the single social practice that offers both compelling illustration and underpinning of such a homology is also one that has rendered Chinese culture extremely distinctive, if not entirely unique, in the long course of its history. Long antedating the time of Confucius, ancestor worship has found ample documentation in the Shang oracle bone inscriptions. This familiar cultural practice within the affairs of the Shang state played a “central, institutionalized role,” because, as Keightley has astutely observed, it “promoted the dead to higher levels of authority and impersonality with the passage of generations, encouraged the genesis of hierarchical, protobureaucratic conceptions and … enhanced the value of these conceptions as more secular forms of government replaced the Bronze Age theocracy.”16

The decisive contribution of Shang ancestral worship was precisely this union in itself of the three realms of power that determine and constrain human existence: the sacral, the biological, and the political. In contrast to the Greek concern for questions of origins, “first causes,” or “first principles,” the more social and biological conception of identity among the Chinese, says Keightley, led to a corresponding concern for “genealogy and history. A hierarchy of ancestors leading back to a dimly perceived founding ancestor or ancestress was answer enough because it satisfied the kinds of questions that were being asked.”17 Although classic Chinese texts did not raise the questions of origin or first cause in the same abstract manner as those of Greek antiquity, there should be no doubt that the name and status of ancestors belong to the realm of the sacred, because their act of procreation was thought to possess primordial significance. Keightley’s insight is, in fact, confirmed by a passage in the section on “Special Livestock for Suburban Sacrifice” (jiaotesheng  ) in the Han anthology Record of Rites (Liji), which declares that because “all things originate from Heaven [and] humans originate from the ancestor, this is why one offers food and drink to the High God or Di. The Suburban Sacrifice magnifies the repayment of origin and the return to the beginning [

) in the Han anthology Record of Rites (Liji), which declares that because “all things originate from Heaven [and] humans originate from the ancestor, this is why one offers food and drink to the High God or Di. The Suburban Sacrifice magnifies the repayment of origin and the return to the beginning [

].”18

].”18

Notice that this statement aligns Heaven ( tian), High God (Di

tian), High God (Di  ), and ancestor (zu

), and ancestor (zu  ) all in a continuum of power, and this power is by definition religious or sacral because it has to do with one’s ultimate origin, the arche of the individual and the community. To dishonor or betray one’s parents and ancestors is to spurn or transgress one’s origin.19 Conversely, because ancestors and Heaven are functional equals in this formula, the sacral significance of parents is enormous, for they are always on their way to becoming ancestors. Hence filial acts, as acts of “repayment of origin and the return to the beginning,” are always sanctioned by Heaven, whereas a statement such as that by Jesus in Matthew 10:34ff. On the cost of discipleship becomes virtually incomprehensible to this day for many Chinese.20

) all in a continuum of power, and this power is by definition religious or sacral because it has to do with one’s ultimate origin, the arche of the individual and the community. To dishonor or betray one’s parents and ancestors is to spurn or transgress one’s origin.19 Conversely, because ancestors and Heaven are functional equals in this formula, the sacral significance of parents is enormous, for they are always on their way to becoming ancestors. Hence filial acts, as acts of “repayment of origin and the return to the beginning,” are always sanctioned by Heaven, whereas a statement such as that by Jesus in Matthew 10:34ff. On the cost of discipleship becomes virtually incomprehensible to this day for many Chinese.20

Although the date of the Record of Rites as a Han anthology, incontestably and thoroughly Confucian in its outlook and authorship, may be separated from the Shang period by close to 1,000 years, the interpretation of the royal sacrifice and its reference to shangdi (high god) may well have articulated an archaic ideal that would far outlive its initial, genetic impact to shape and influence subsequently vast stretches of imperial culture. Keightley’s words from another source must be cited:

Shang religion was inextricably involved in the genesis and legitimation of the Shang state. It was believed that Ti [Di], the high god, conferred fruitful harvest and divine assistance in battle, that the king’s ancestors were able to intercede with Ti, and that the king could communicate with his ancestors. Worship of the Shang ancestors, therefore, provided powerful psychological and ideological support for the political dominance of the Shang kings. The king’s ability to determine through divination, and influence through prayer and sacrifice, the will of the ancestral spirits legitimized the concentration of political power in his person. All power emanated from the theocrat because he was the channel, “the one man,” who could appeal for the ancestral blessings, or dissipate the ancestral curses, which affected the commonality.21

Keightley’s observation calls attention to the pivotal role of the political leader or sovereign in mediating religious meaning and participation in religious activities as an integral function of his political authority. Such a function, I must emphasize, has remained constant in all of Chinese imperial history, for the emperor or sovereign was never exempted from the duty to offer appropriate sacrifices, to ancestors and to other related transcendent powers variously conceived, that were deemed crucial for the state’s health and well-being.

The most significant development in respect to the union of religion, politics, and kinship structures in China’s imperial history-the phenomenon that some scholars have termed “institutionally diffuse religion”22 came at the moment when the first emperor of China took for his dynastic title the name Qin Shihuangdi  (First August Emperor of Qin) in 221 B.C. The word for emperor here is indeed di, frequently translated as God in the scholarship on Shang religion and chosen by Mateo Ricci (1552–1610) centuries later as the appropriate nomenclature for the Christian deity. Vatican rejection in the Rites controversy led to Ricci’s eventual choice of the term tianzhu

(First August Emperor of Qin) in 221 B.C. The word for emperor here is indeed di, frequently translated as God in the scholarship on Shang religion and chosen by Mateo Ricci (1552–1610) centuries later as the appropriate nomenclature for the Christian deity. Vatican rejection in the Rites controversy led to Ricci’s eventual choice of the term tianzhu  , but di was revived by Protestant missionaries in the nineteenth century, and the term shangdi since has existed for nearly two centuries in their biblical translation as another accepted name for God. Even more significantly for our discussion here is the fact that the term di may, as a number of scholars have argued, etymologically connote the sense of ancestor.23 When, therefore, the first emperor who united China assumed this title for himself, that single name would weave together in itself the related strands of Chinese conceptions of transcendent origin, paternity, authority, and power.

, but di was revived by Protestant missionaries in the nineteenth century, and the term shangdi since has existed for nearly two centuries in their biblical translation as another accepted name for God. Even more significantly for our discussion here is the fact that the term di may, as a number of scholars have argued, etymologically connote the sense of ancestor.23 When, therefore, the first emperor who united China assumed this title for himself, that single name would weave together in itself the related strands of Chinese conceptions of transcendent origin, paternity, authority, and power.

As if fearing that this single term would be insufficient to make apparent the symbolic significance of the ruler, the word zu, a much more common term for ancestor, was incorporated into the dynastic title of the first emperor of the Han. Henceforth, in the different appellations of individual reigns since 206 B.C., the ruler named as di or zu could mean quite literally that the ruler was a “god of martial prowess” (wudi  ) or “high ancestor” (gaozu

) or “high ancestor” (gaozu  ), as many of them were called. Still later, in the opening years of the Tang, the dynastic title of the second emperor was established as taizong

), as many of them were called. Still later, in the opening years of the Tang, the dynastic title of the second emperor was established as taizong  (supreme ancestor). With this string of names forever canonized in the official annals of imperial history, as one can see, transcendence has been nominally immanentalized and made familiar as kin, but such appellations also purport to indicate unambiguously that the ruler’s power and authority remain godlike and, therefore, absolute. Moreover, they are meant to facilitate the venerable understanding obtaining even in Confucius’s time that between state and family there exists a complete and practicable homology.24 If the ruler, king, or emperor is, in fact, the grand ancestor of his subjects, political virtues must find their expression in kinship terms, much as the household patriarch, the rulerlike paterfamilias, will be enabled by such discursive propping to reign with impunity as god and ruler within his family and clan.

(supreme ancestor). With this string of names forever canonized in the official annals of imperial history, as one can see, transcendence has been nominally immanentalized and made familiar as kin, but such appellations also purport to indicate unambiguously that the ruler’s power and authority remain godlike and, therefore, absolute. Moreover, they are meant to facilitate the venerable understanding obtaining even in Confucius’s time that between state and family there exists a complete and practicable homology.24 If the ruler, king, or emperor is, in fact, the grand ancestor of his subjects, political virtues must find their expression in kinship terms, much as the household patriarch, the rulerlike paterfamilias, will be enabled by such discursive propping to reign with impunity as god and ruler within his family and clan.

THE HOMOLOGY OF VIRTUES

To be fair to the historical Confucius (551–479 B.C.), his teachings-at least those collected in the Analects-have little to say about ancestors as such, but we must remember as well that they never dispute the important necessity of sacrifices (ji  ), including those established for ancestors (e.g., Analects 2.5, 24). Although there are only a few remarks about parents (fumu

), including those established for ancestors (e.g., Analects 2.5, 24). Although there are only a few remarks about parents (fumu  ) and father scattered throughout the Analects, it cannot be denied that his observations on filial piety (xiao

) and father scattered throughout the Analects, it cannot be denied that his observations on filial piety (xiao  ) in conjunction with how to serve one’s parents (shi fumu

) in conjunction with how to serve one’s parents (shi fumu  , e.g., Analects 1.7; 4.18) and how to serve one’s ruler (shi jun

, e.g., Analects 1.7; 4.18) and how to serve one’s ruler (shi jun  , Analects 1.7; 3.18–19; 11.12; 14.22) are more abundant throughout his collected sayings. Significant in this regard is the homologous relationship already drawn by Confucius between service to one’s family and that to the state. When queried by someone as to why he was not taking part in government, Confucius replied:

, Analects 1.7; 3.18–19; 11.12; 14.22) are more abundant throughout his collected sayings. Significant in this regard is the homologous relationship already drawn by Confucius between service to one’s family and that to the state. When queried by someone as to why he was not taking part in government, Confucius replied:

The Book of History says, “oh! Simply by being a good son and friendly to his brothers a man can exert an influence upon government.” In so doing a man is, in fact, taking part in government. How can there by any question of his having actively to “take part in government”?25

Herein lies the seed for his famous doctrine adumbrated in the Great Learning that the state’s proper governance (zhi guo  ) must be a direct consequence of one’s success in regulating one’s family (qi jia

) must be a direct consequence of one’s success in regulating one’s family (qi jia  ) and the cultivation of oneself (xiu shen

) and the cultivation of oneself (xiu shen  ). The putative commentary on this doctrine by his disciple Zeng Shen

). The putative commentary on this doctrine by his disciple Zeng Shen  , with a pointed allusion to the Analects text cited above, makes the connection even more taut and explicit:

, with a pointed allusion to the Analects text cited above, makes the connection even more taut and explicit:

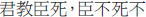

What is meant by “in order rightly to govern the State, it is necessary first to regulate the family,” is this: It is not possible for one to teach others, while he cannot teach his own family. Therefore, the gentleman, without going beyond his household [or clan], completes the lessons for the State [

]. There is filial piety: therewith the sovereign should be served [

]. There is filial piety: therewith the sovereign should be served [

]. There is fraternal submission: therewith elders and superiors should be served. There is kindness: therewith the multitude should be treated.26

]. There is fraternal submission: therewith elders and superiors should be served. There is kindness: therewith the multitude should be treated.26

This comment indicates clearly the appropriation of an essentially family virtue, xiao (filial piety), and its direct application to the political realm, all as part of the gradation of ethical obligations in accordance with social rankings. In another instant, the Han Record of Rites will grandly argue how altruism and administration of justice are directly dependent on the proper filial regard for clan ancestors and kin. In the section titled “Great Commentary” (Da zhuan  ), we find this remarkable summation, which deserves full citation:

), we find this remarkable summation, which deserves full citation:

Now kinship is the bond of connection. Where the starting point is affection, one begins with the father and ascends by rank to the ancestor; where the starting point is rightness, one begins with the ancestor and descends in natural order to the deceased father [note how hierarchy privileges the distant over the recent]. Thus the way of humans is to love one’s parents [shi gu rendao qinqin ye  ]. Because one loves one’s parents, one honors the ancestors; honoring one’s ancestors, one also reveres the clan. Because one honors the clan, one also keeps together the members of the family branches. Keeping together these members dignifies the ancestral shrine; dignifying the ancestral shrine, one attaches great importance to the altars of land and grain. Valuing the altars, one therefore loves the hundred names [the metaphor for the people], and when one loves the people, there will be the accurate administration of punishment and penalty. When punishment and penalty are accurate, the ordinary people will find security, and when people are secure, resources and expenditures will both suffice.27

]. Because one loves one’s parents, one honors the ancestors; honoring one’s ancestors, one also reveres the clan. Because one honors the clan, one also keeps together the members of the family branches. Keeping together these members dignifies the ancestral shrine; dignifying the ancestral shrine, one attaches great importance to the altars of land and grain. Valuing the altars, one therefore loves the hundred names [the metaphor for the people], and when one loves the people, there will be the accurate administration of punishment and penalty. When punishment and penalty are accurate, the ordinary people will find security, and when people are secure, resources and expenditures will both suffice.27

Since the anthology defines the clan as those who share in the patrilineal name (tong xing cong zong  ),28, this passage makes plain that the needs and aspirations of the basic family unit, whether the king’s household or the commoner’s, must first be satisfied before attention can be directed to other units. The crucial turn in this line of argument comes in the somewhat puzzling contention that love of people would derive from the regard for the altars of land and grain. In the context of Confucian writings, however, one point seems evident: altruism is thought to be motivated primarily through the concerns of self-preservation, concretely expressed in the attempt to maintain sufficient sustenance for proper sacrifices to one’s ancestors. Distributive justice in the Confucian view thus cannot be premised on the equal provision of justice for the constituent members of society, irrespective of kinship affiliations, because in principle, what is due the people (the hundred names [baixing

),28, this passage makes plain that the needs and aspirations of the basic family unit, whether the king’s household or the commoner’s, must first be satisfied before attention can be directed to other units. The crucial turn in this line of argument comes in the somewhat puzzling contention that love of people would derive from the regard for the altars of land and grain. In the context of Confucian writings, however, one point seems evident: altruism is thought to be motivated primarily through the concerns of self-preservation, concretely expressed in the attempt to maintain sufficient sustenance for proper sacrifices to one’s ancestors. Distributive justice in the Confucian view thus cannot be premised on the equal provision of justice for the constituent members of society, irrespective of kinship affiliations, because in principle, what is due the people (the hundred names [baixing  ]-a number that, incidentally and ironically, remains largely intact in twenty-first century China to provide family or surnames to 1.3 billion plus people!) is meted out in a centrifugal movement from the family or clan as the anchoring unit of that society. If that fundamental unit fails in its filial obligations, according to the logic of the passage cited above, the rest of society cannot hope to find security or even the proper administration of retributive justice (punishment and penalty).

]-a number that, incidentally and ironically, remains largely intact in twenty-first century China to provide family or surnames to 1.3 billion plus people!) is meted out in a centrifugal movement from the family or clan as the anchoring unit of that society. If that fundamental unit fails in its filial obligations, according to the logic of the passage cited above, the rest of society cannot hope to find security or even the proper administration of retributive justice (punishment and penalty).

Such an understanding of altruism will accord with how the cardinal virtue of ren  has been glossed and developed by Confucius and his follower. Antedating, in fact, the Confucians, an ancient source like the Classic of Documents already hints at the intimate association between ren-a word that has been variously rendered in English as benevolence, humaneness, human-heartedness, and even sublime generosity of the soul-and virtues valorized in clan rules and ethics (zongfa lunli

has been glossed and developed by Confucius and his follower. Antedating, in fact, the Confucians, an ancient source like the Classic of Documents already hints at the intimate association between ren-a word that has been variously rendered in English as benevolence, humaneness, human-heartedness, and even sublime generosity of the soul-and virtues valorized in clan rules and ethics (zongfa lunli  ). In the scribal prayer preserved in the section titled “Metal Bond” (jinteng

). In the scribal prayer preserved in the section titled “Metal Bond” (jinteng  ), the clause “we are kindly as well as filial” (yu ren ruo kao = xiao

), the clause “we are kindly as well as filial” (yu ren ruo kao = xiao

) has been read by a modern authority as “we are obedient to the will of our ancestors.”29 The observation by Fan Wenzi

) has been read by a modern authority as “we are obedient to the will of our ancestors.”29 The observation by Fan Wenzi  recorded in the Zuo Commentary also asserts that “not forgetting one’s origin is ren [

recorded in the Zuo Commentary also asserts that “not forgetting one’s origin is ren [ ].”30 Again, the words of Li Ji

].”30 Again, the words of Li Ji  , set down in the “Jinyu” (

, set down in the “Jinyu” ( ) section of the Guoyu

) section of the Guoyu  , declare that “for those who practice benevolence, loving one’s parents is called ren [

, declare that “for those who practice benevolence, loving one’s parents is called ren [

].”31 Finally, we have, included with obvious approbation in the Analects itself, the statement by the philosopher Youzi

].”31 Finally, we have, included with obvious approbation in the Analects itself, the statement by the philosopher Youzi  (or You Ruo

(or You Ruo  ) that “being a filial son and an obedient brother is the root of ren [

) that “being a filial son and an obedient brother is the root of ren [

].”32 As we shall see momentarily, this conclusion makes sense only in the context of the rationale structured in the entire assertion of the philosopher.

].”32 As we shall see momentarily, this conclusion makes sense only in the context of the rationale structured in the entire assertion of the philosopher.

Read together with the declarations cited, the gloss preserved in the Doctrine of the Mean is both illuminating and instructive. “Ren is people,” declares the text, “but loving one’s parents is its greatest [manifestation] [ ]” (20). This explicit exegesis provided by the second clause finds repeated and sympathetic echoes in a text like Mencius, which reiterates the same definition: “Loving one’s parents is benevolence [

]” (20). This explicit exegesis provided by the second clause finds repeated and sympathetic echoes in a text like Mencius, which reiterates the same definition: “Loving one’s parents is benevolence [

]” (7A.15). For Mencius the philosopher, ren is an affect that obtains primarily and most fully between parent and child, in such a special way, in fact, that one may regard it as something as natural or decreed (see 7B.24: “The way benevolence pertains to the relation between father and son … is the Decree, but therein also lies human nature [

]” (7A.15). For Mencius the philosopher, ren is an affect that obtains primarily and most fully between parent and child, in such a special way, in fact, that one may regard it as something as natural or decreed (see 7B.24: “The way benevolence pertains to the relation between father and son … is the Decree, but therein also lies human nature [

]”). In another passage (7A.45), Mencius differentiates the proper affect toward kin and nonrelations with this striking gradation:

]”). In another passage (7A.45), Mencius differentiates the proper affect toward kin and nonrelations with this striking gradation:

Toward living creatures a gentleman would be sparing but show them no benevolence; toward the people he would show benevolence but not love. [only] when he loves his parents would he show [proper] benevolence to the people. When he shows people benevolence, he would be sparing toward the living creatures [

].33

].33

The logic of Mencius and the compilers of the Han anthology on rites, as we can see, remains consistent, because according to them, one cannot even show benevolence to the people (ren min) without first loving one’s parents (qin qin).

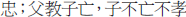

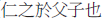

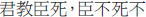

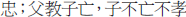

By what I have called here the homology of virtues, Confucians have insistently maintained that the most intimate affect appropriate to a kinship environment (the home, the household, the clan) and the ethical action thus formed and motivated are literally and equally applicable outside that environment. Since in imperial principle there is no space “under Heaven that is not the ruler’s territory,” the domain of the state both encircles and encompasses the domestic one. United, moreover, in symbolic significance in the person of the patriarch are the figures of the sovereign and the father, and it is this equation that grants viability and authority to the ethical homology. According to the Confucian formula set forth in the Classic of Filial Piety (Xiaojing  ),

),

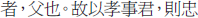

when we take that by which we serve the father to serve the mother, the love is the same. When we take that by which we serve the father to serve the ruler, the reverence is the same. Thus the mother takes one’s love, whereas the ruler takes one’s reverence. He who takes both is the father. Therefore, when one uses filial piety to serve one’s ruler, he will be loyal [

].34

].34

Notice that the logic implied in the above passage is what enables the Confucian to posit that the obverse of such prescriptive behavior is equally true: i.e., when one serves the ruler with loyalty, the person must be a filial son  .

.

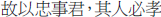

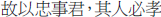

Only in the light of such reasoning can one grasp to the fullest extent the powerful argument of You Ruo’s assertion preserved so prominently in the Analects 1.2:

For a man who is both filial and obedient as a younger brother, it is rare that such a person would love to affront his superiors [fan shang  ]. In fact, there has never been such a person who, being disinclined to affront his superiors, is still fond of inciting a rebellion [zuo luan

]. In fact, there has never been such a person who, being disinclined to affront his superiors, is still fond of inciting a rebellion [zuo luan  ]. A gentleman works at his roots; once the roots are established, the Way will grow therefrom. Are not filial piety and being obedient as a brother the roots of humaneness [ren]?

]. A gentleman works at his roots; once the roots are established, the Way will grow therefrom. Are not filial piety and being obedient as a brother the roots of humaneness [ren]?

Filial piety, a practice of personal rectitude, is now decisively recognized for its true worth-an apposite model for public political virtue-because its attitudinal assumptions and behavioral manifestations (i.e., “the roots”) can benefit not merely parents and kin but also supremely those in power and authority.

The Confucian discourse, moreover, does not emphasize this homology of virtue merely to shore up the formulated claims of personal and domestic ethics. In its writing the state and history, this line of teaching serves as one linchpin of its overall world-regulating (jingshi  ) intent and design, as when the phrase qinqin is expanded from the basic meaning of loving one’s parents to the love or regard for one’s blood kin within a primarily political context. Witness the pronouncement on the defeat of Earl Xi

) intent and design, as when the phrase qinqin is expanded from the basic meaning of loving one’s parents to the love or regard for one’s blood kin within a primarily political context. Witness the pronouncement on the defeat of Earl Xi  by Duke Zheng

by Duke Zheng  : among the several causes mentioned that would seal the former’s destruction, the historian-commentator included the observation that Xi did not cherish kin relations (bu qinqin), for his feuding with Zheng represented a repudiation of the fact that they had the same surname.35 Even in realpolitik, apparently, the obligations and demands of kinship retain their normative force. Why such a construct of human relations conjoining ancestry, paternity, rulership, and ethics succeeds in such a compelling and lasting fashion has been well summarized by a contemporary scholar:

: among the several causes mentioned that would seal the former’s destruction, the historian-commentator included the observation that Xi did not cherish kin relations (bu qinqin), for his feuding with Zheng represented a repudiation of the fact that they had the same surname.35 Even in realpolitik, apparently, the obligations and demands of kinship retain their normative force. Why such a construct of human relations conjoining ancestry, paternity, rulership, and ethics succeeds in such a compelling and lasting fashion has been well summarized by a contemporary scholar:

It was the ancestors who created the human species, and while all humans were “born equal,” they were “equal” in the sense of being equally human and different from animals. Moreover, only humans could recognize ancestors. Thus ancestors took precedence over nature. Thus also filial piety quite rapidly became a core value in the Chinese web of interpersonal relationships, an axis linking the individual human being, his family, and his society. By the Han dynasty, filial piety had already become institutionalized as a criterion for selection of persons into officialdom.36

In the light of Youzi’s observation, that criterion could not be more appropriate!

THE CONTEMPORARY DEBATE

Certain scholars who would like to reconcile classical Confucian teachings with liberal political thought of the West and the contemporary promotion of human rights frequently attempt to do so on the supposed basis that “the true person [in the Chinese tradition] is construed as a thoroughly social being.”37 This anthropological concept is in turn construed usually as an epitome of the desirable emphasis on moral duties and obligations. For many observers of China, the Confucian exaltation of group over individual is not even simply a legacy of a single culture. To the extent that historical Confucianism has been a known cultural export over the centuries, East and South Asian societies deeply influenced by such traffic are also indisputably implicated. The extent of Confucian impact in a particular society, whether as a result of conscious promotion (Korea, Tokugawa Japan, contemporary Singapore, Nationalist China on Taiwan) or as lingering habits of thought and action in diaspora communities, may be variously measured. The effect of its undeniable presence, however, has often been praised, for the principal emphasis on state and family over the individual person is routinely touted as a core element of the so-called Asian values that would effectively curb what are perceived as the corrosive excesses of Western individualism. In a much quoted interview, Lee Kuan Yew declares that

Eastern societies believe that the individual exists in the context of his family. He is not pristine and separate. The family is part of the extended family, and then friends and the wider society. The ruler or the government does not try to provide for a person what the family best provides.38

Sharpening the polemical tone of the debate, Ian Buruma, in his review of the recent book by Hong Kong’s last governor, Christopher Patten, has this observation:

Patten’s experience in Hong Kong made him reexamine his political instincts. And he concluded that his taste for free market economics, the rule of law, and the universality of liberal ideas was more than a matter of instinct. These were big ideas. And the propaganda for “Asian values,” putting loyalty to the state above individual liberty, and duty and obedience above democratic rights, was a challenge to the Big Ideas: Lee Kuan Yew versus Locke, Mahathir versus Adam Smith. Was the “Asian” combination of capitalist economics and authoritarian rule exceptional?39

Possible answers to Buruma’s rhetorical question divide even further those scholars interested in accommodating or reconciling the so-called Asian reality with both contemporary economics and politics. In the view of Hong Kong’s Ambrose King, who thinks that the “East Asian experience demonstrates that democracy and modernity are not necessarily inseparable from individualism,” the ideal would be the development of a “democratically Confucian political system or society” in which human rights are to be defined in “communal” or “social” terms.40 For King as for others sympathetic to the accentuation of “communitarian” values, the Confucian tradition seems to be a rich and viable cultural resource for instilling and reinforcing such values. Thus, according to Sumner Twiss, “human rights in general are compatible in principle not only with cultural traditions that emphasize the importance of individuals within community (which is a more apt characterization of Western liberalism) but also with cultural traditions that may emphasize the primacy of community and the way that individuals contribute to it-that is, both more liberal individualist and more communitarian traditions.”41

Such a line of argument dwelling on “communitarian values” and the human person as a “social being,” regrettably, tends to de-emphasize or overlook the fact that in Confucian teachings, different social groups have different ethical and political claims on that “social being.” It tends to forget as well that in the Confucian state, groups, communities, classes, and stratifications that constitute and define all those relations (lun) are no more equal than the individual. On the other hand, as one historian in the very first volume of the The Cambridge History of China has observed, already discernible among the trends characteristic of intellectual development from the period of the Warring States (403–221 B.C.) to the Han and beyond would be an “emphasis on the ideal of social harmony, albeit a harmony based on inequality. In other words, the emphasis is on the readiness of each individual to accept his particular place in a structured hierarchy, and to perform to the best of his ability the social duties that pertain to that place.”42 It need hardly be said that such an emphasis would find the staunchest support and the most eloquent exposition in the Confucian elite, who at every opportunity seems ready to draw on the state-family homology to buttress the cardinal principles of rulership. Thus in the chapter on “Governing the Family” (Zhijia  ) in his pioneering Manual for Family Instruction (Jiaxun

) in his pioneering Manual for Family Instruction (Jiaxun  ), which became the model for countless subsequent imitations, the Sui official Yan Zhitui

), which became the model for countless subsequent imitations, the Sui official Yan Zhitui  (531–591) bluntly declares, “When the anger expressed by the cane is abolished in one’s house, the faults of the rebellious son immediately appear. When punishment and penalty are inaccurate, the people have no basis even to lift their hands and feet. Leniency and severity in governing one’s house are the same as those in the state.”43 And, even if Confucius himself did not initiate the practice of ancestor worship, this ancient ritual and its correlative ideal of filial piety, as we have seen, were already deftly appropriated by his first and second generation disciples as decisive expressions of domestic propriety, itself deemed indispensable for political order. Under the impact of Neo-Confucian revivalism of the Song onward, in fact, the ancestral cult and its rituals would not only crowd the pages of the popular genre of family instruction manuals, but the design and erection of the family shrine, a custom increasingly adopted by Song elite officials, would come to dominate even domestic architecture as well.44

(531–591) bluntly declares, “When the anger expressed by the cane is abolished in one’s house, the faults of the rebellious son immediately appear. When punishment and penalty are inaccurate, the people have no basis even to lift their hands and feet. Leniency and severity in governing one’s house are the same as those in the state.”43 And, even if Confucius himself did not initiate the practice of ancestor worship, this ancient ritual and its correlative ideal of filial piety, as we have seen, were already deftly appropriated by his first and second generation disciples as decisive expressions of domestic propriety, itself deemed indispensable for political order. Under the impact of Neo-Confucian revivalism of the Song onward, in fact, the ancestral cult and its rituals would not only crowd the pages of the popular genre of family instruction manuals, but the design and erection of the family shrine, a custom increasingly adopted by Song elite officials, would come to dominate even domestic architecture as well.44

This Confucian insistence on the priority of sociopolitical relations embedding the individual and their immutable claims on that person has not been spared from fierce critique by a wide group of Chinese intellectuals early in the twentieth century. When one examines, for example, the content of the polemics that made famous the early republican iconoclast Chen Duxiu (Ch’en Tu-hsiu  [1879–1942]), one can readily discern that his attack of Confucian ideals and practices was based squarely on the charge that they had historically deprived major social groups like “sons and wives” of their “personal individuality” and “personal property.”45 Although Chen eventually became one of the leading theoreticians for the Chinese Communist Party, which succeeded in building probably the most totalitarian state known in Chinese history, it should be remembered as well that his early contributions to the intellectual ferment of his time stemmed again from the conviction, shared by many of the so-called May Fourth thinkers, that what the new and modern needed in China was a revolutionary discovery and appreciation of the individual.46

[1879–1942]), one can readily discern that his attack of Confucian ideals and practices was based squarely on the charge that they had historically deprived major social groups like “sons and wives” of their “personal individuality” and “personal property.”45 Although Chen eventually became one of the leading theoreticians for the Chinese Communist Party, which succeeded in building probably the most totalitarian state known in Chinese history, it should be remembered as well that his early contributions to the intellectual ferment of his time stemmed again from the conviction, shared by many of the so-called May Fourth thinkers, that what the new and modern needed in China was a revolutionary discovery and appreciation of the individual.46

Although it is true that there had not been many persons who “declared themselves anti-Confucian” resolutely during more than two millennia of Chinese imperial history, as Chow Tse-tsung has remarked,47 the fortunes of Confucianism in the twentieth century, understandably more varied because of vast and cataclysmic change, have fluctuated between hostile opposition and arduous rehabilitation both on the mainland and in diaspora communities elsewhere.48 The gyrating vicissitudes of Confucian reception in recent Chinese experience are thus not only conducive to creating immense historical ironies, but those ironies themselves may also betoken the ongoing but halting efforts on the part of the Chinese to come to terms with part of their most cherished and stubborn cultural legacy. Within the People’s Republic itself, at times sponsoring not merely virulent attacks on the person and ideals of the ancient sage but also brutal attempts to uproot virtually all traces of the tradition, there has been nonetheless in the post-Mao period some movement also to retrieve and revive a Confucius more compatible with its own understanding of national modernity. On the other hand, in an island nation like Taiwan, which prides itself as the keeper and sustainer of genuine Confucian values in both government and society,49, the last two decades of the twentieth century have witnessed the flowering of stringent critique, a discourse of ressentiment unsparing in both scope and severity against this venerable tradition even as the nation strives to become a full-fledged democracy enjoying unprecedented forms of freedom.

Among sinological savants working outside of China, there are those who would advocate the retention and possibly the revival of Confucianism by contending that its principal tenets may have even anticipated certain aspects of Western liberalism and that the Confucian insistence on the priority of sociopolitical relations embedding the individual may not be incompatible with the Western discourse of human rights. Thus in his thoughtful essay of 1979, Wang Gungwu had already anticipated much of the rhetoric and tactics employed by contemporary Confucian loyalists by trying to link “the idea of reciprocity” with the “idea of implicit rights.” Adducing from various prescriptions in the Analects, the Zuo Commentary, and Mencius for the ideal behavior appropriate to various social ranks (e.g., “The ruler should treat the subject with propriety, the subject should serve the ruler with loyalty”), Wang would argue that these duties and obligations might well be thought of as a form of rights, in the sense of reciprocal obligations categorically demanded of the sovereign, the subject, the father, the son, and the spouses.50 Similar arguments have also been repeatedly advanced by Tu Weiming and Wm. Theodore de Bary.

According to the latter, the long line of elite officials studding Chinese imperial history and nurtured in both the letter and spirit of Confucian orthodoxy could be seen to have among its ranks a number of thinkers whose political philosophy seemed to promise transcendence over its own cultural ethos and limitation. Noted late medieval figures like Wang Fuzhi  (1619–1692), Huang Zongxi

(1619–1692), Huang Zongxi  (1610–1695), and Tang Zhen

(1610–1695), and Tang Zhen

(1630–1704) could be gathered in what might be called the liberal tradition of China, because they clung to the Confucian insistence of the subject’s duty of fearless remonstrance and advocated in their writings various forms of “egalitarianism.”51 It is this tradition, in the view of de Bary and other like-minded colleagues, that may even help explain how a certain phrase of Confucian rhetoric, first proposed by the then existent Republic of China, came to find adoption in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, ratified by members of the United Nations in 194852.

(1630–1704) could be gathered in what might be called the liberal tradition of China, because they clung to the Confucian insistence of the subject’s duty of fearless remonstrance and advocated in their writings various forms of “egalitarianism.”51 It is this tradition, in the view of de Bary and other like-minded colleagues, that may even help explain how a certain phrase of Confucian rhetoric, first proposed by the then existent Republic of China, came to find adoption in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, ratified by members of the United Nations in 194852.

Humane and persuasive as such a line of argument may seem, the problem lies in its failure to confront squarely the issue that, although the concept of reciprocity in Confucian thinking refers to “differentiated but mutual and shared”53 obligations, they are for that very reason not equal claims or obligations. De Bary is fond of citing the Mencian passage in 3A.4 where different obligations are spelled out for different classes of people: for example, affection between parent and child, rightness between ruler and ministers, distinctive duties for spouses, gradation for old and young, and trustworthiness between friends.54 This schematization, unfortunately, is always upheld without the concomitant but necessary acknowledgment that even these five relations and their idealized obligations themselves embody an inherent hierarchical preference. Since our debate involves the consideration of textualized tradition and historical reality, we must again refer to the Record of Rites, in which the section “Jitong” ( [Summary of Sacrificial Principles]) declares that

[Summary of Sacrificial Principles]) declares that

in sacrifices are ten relations which may be seen in the way of serving the ghosts and spirits, in the obligations between ruler and subject, in the relation between father and son, in the ranks dividing the noble and the lowly, in the distance separating the kin, in the bestowal of title and reward, in the distinction of duties between husband and wife, in the impartiality of governmental affairs, in the observance of order between old and young, and in the boundaries set between high and low.55

This statement has elicited in turn from Fei Xiaotong  (Fei Hsiaot’ung, 1910–2005), the father of sociology in modern China, the observation that “Lun [relations] is order based on classifications” conceived on the very commingling of “concrete social relationships” with “abstract positional types [e.g., noble and lowly, high and low].” According to him, “the basic character of traditional Chinese social structure rests precisely on such hierarchical differentiations…. Therefore, the key to understanding networks of human relationships is to recognize that such distinctions create the very patterns of Chinese social organization.” Because “the framework of social structure” confuses the symmetric and asymmetric models of the social and remains “unchangeable”56 unless the very categories for its construction are dismantled or reconceived, the thesis of contemporary Confucian revivalists-that the ideal of moral reciprocity prescribed for those relations would provide an adequate analogue to the concept of right-becomes highly questionable.

(Fei Hsiaot’ung, 1910–2005), the father of sociology in modern China, the observation that “Lun [relations] is order based on classifications” conceived on the very commingling of “concrete social relationships” with “abstract positional types [e.g., noble and lowly, high and low].” According to him, “the basic character of traditional Chinese social structure rests precisely on such hierarchical differentiations…. Therefore, the key to understanding networks of human relationships is to recognize that such distinctions create the very patterns of Chinese social organization.” Because “the framework of social structure” confuses the symmetric and asymmetric models of the social and remains “unchangeable”56 unless the very categories for its construction are dismantled or reconceived, the thesis of contemporary Confucian revivalists-that the ideal of moral reciprocity prescribed for those relations would provide an adequate analogue to the concept of right-becomes highly questionable.

Since the Confucian notion of reciprocity always embodies preference and priority, it must perforce enjoin unequal sanctions against disparate social ranks in the event of legal infraction, a notion directly contradicting the modern Western conception of equality before the law. Because humans cannot avoid or escape moral failures, the question that Confucianism must confront is not about the necessity to inculcate and practice virtue, or even about the possibility of “self-renewal” (zixin  ) and “selfcorrection” (gaiguo

) and “selfcorrection” (gaiguo  ).57 In the public realm of society, it has to do rather with what happens when virtue fails and how will those in power be held accountable. Subjects, wives, children, and inquisitive journalists may be swiftly penalized if they err, but who will effectively censure, curb, or bring to justice the transgressive emperor, the patriarch, the judge, the senior minister, or the members of the ruling party? The question of human rights, in this context, is not about mutual kindness, assistance, and cooperation, however noble such acts may be in themselves. Rather, it is about the lower and lowest levels of human society and what recourse they have and do not have when they are abused and ill-treated. Must they rely merely on the “fearless remonstrance of loyal ministers” that de Bary’s books exalt repeatedly? Are exile, imprisonment, or remonstration till execution the exemplary fate met by worthies in the Shang and singled out for praise by Confucius in the Analects 18.1-the only viable alternatives when rulers and subjects disagree in a contemporary Asian society?

).57 In the public realm of society, it has to do rather with what happens when virtue fails and how will those in power be held accountable. Subjects, wives, children, and inquisitive journalists may be swiftly penalized if they err, but who will effectively censure, curb, or bring to justice the transgressive emperor, the patriarch, the judge, the senior minister, or the members of the ruling party? The question of human rights, in this context, is not about mutual kindness, assistance, and cooperation, however noble such acts may be in themselves. Rather, it is about the lower and lowest levels of human society and what recourse they have and do not have when they are abused and ill-treated. Must they rely merely on the “fearless remonstrance of loyal ministers” that de Bary’s books exalt repeatedly? Are exile, imprisonment, or remonstration till execution the exemplary fate met by worthies in the Shang and singled out for praise by Confucius in the Analects 18.1-the only viable alternatives when rulers and subjects disagree in a contemporary Asian society?

The question of how the ruling classes are to be judged, in fact, finds an illuminating discussion in a well-known passage of Mencius. When a subject fails in his duties, according to Confucian doctrine, he may be killed after the ruler has made a thorough investigation of the matter (Mencius 1B.7). On the other hand, even a tyrant as famous as the last king of the Shang could not induce Mencius to permit regicide as a general principle. Since, however, Mencius could not alter recorded history, his justification for killing Zhou, the last king of Shang, was ingenious: the latter had degraded himself so badly by his immoral despotism that he could no longer be classified as king, but merely “a fellow” (yi fu  ). Hermeneutics had thereby saved both official history and morality, for then Mencius could declare resoundingly: “I have heard that a fellow Zhou had been executed, but I have not heard that a sovereign had been executed” (1B.8).

). Hermeneutics had thereby saved both official history and morality, for then Mencius could declare resoundingly: “I have heard that a fellow Zhou had been executed, but I have not heard that a sovereign had been executed” (1B.8).

History, however, may prove to be more stubbornly intractable than this brilliant piece of sophistry. Despite Mencius’s unambiguous and repeated counsel that the people and the officials have what seems a right to leave and abandon an unprincipled or evil ruler, thereby depriving him of his so-called legitimacy (4B.4),58 what is recorded in history presents a wholly different picture. In the long annals of the Chinese tradition, there has not been a single change of dynastic power without violence and bloodshed. On the contrary, even the infrahousehold competition for power between, say, a crown prince and his rival siblings or cousins, more often than not begin and end in the sword, the rope, or the poisonous cup. The only accounts of peaceful transmission of rulership are those attributed to the reigns of the sage-kings Yao, Shun, and Yu, but their mythic status at the dawn of Chinese history should also warn us that their examples betoken more of Chinese desire than veracity.

This irrefutable phenomenon of Chinese history, I would argue, indicates something more than the unavoidable clash “between ideal values and their implementation in historical practice,”59 a judgment that smacks more of romantic hermeneutics pervasive of certain phases of scholarship treating Buddhist and Christian histories than a sound conclusion. In that view, the founding ideals of these two traditions are allegedly so rarefied and pure that they were almost immediately misunderstood by their followers; they can be recovered only by the sympathetic perspicacity of modern interpreters. For me, rather, the basis for doubting the Confucian tradition and its modern viability must center on something more fundamental: namely, the essentially biological model of the patriarchal family and its use as a luminous mirror of the state that Confucians had extolled from the beginning. One may well ask whether the family, even at the level of a large, extended household of the clan, can justly reflect the complexity and the necessity of impersonal arbitration that must obtain in the political body of a contemporary nation. Can such a family model provide the adequate underpinning for the ideals of social equality and minimal human rights? I suspect not, not because the Chinese do not or cannot envision such ideals as desirable ends, as some advocates of cultural particularism have erroneously argued, but because the model itself long cherished and defended by the Confucian discourse is not conducive to the establishment of these ends.60

Even in extremely liberal societies today, families are not thought to be organized around a scripted and contracted system of rights but fundamentally by an unspoken or loosely specified code of duties, obligations, and expectations that are posited as the proper behavior of kinship. This is the reason why in the United States today there is growing vexation, in the courts no less than in social commentary, as to when and how the impersonal state should intervene when the fundamental rights of citizens as household members are violated or denied by other members of the same household.61 By contrast, Confucius and his disciples, as I have tried to show, have articulated a meticulously specified code that directly grounds political virtues on familial ones. The logical question that must be asked at every formulation of Confucian social and personal ethics is this: what recourse does a Chinese have when such prescribed norms are not observed or abused, that is when reciprocity is withheld or rejected? Confucius was forthright in answering a disciple’s query by declaring: “The ruler should employ his subject according to the rules of propriety; the subject should serve his ruler with loyalty.” But the question the disciple failed to bring up next is: what happens when the ruler fails the rules of propriety? As we have seen already in the Mencian discussion of tyranny, that ruler’s failure has enormous consequence, because the philosopher recognizes clearly the possibility that “innocent people” could be killed by such a person (Mencius 4B.4). Here the classic Confucian homology of the state and family breaks down.