SECRETS UNCOVERED

“I go on cutting and examining buboes.”

—Alexandre Yersin, 1894

In June 1894, just a month after the Hong Kong epidemic began, two researchers arrived in the colony, determined to solve plague’s mysteries.

The men came from different countries and spoke different languages. But they shared the belief that through the science of bacteriology, they could discover plague’s cause. Once they did, they would be able to prevent and cure a disease that had haunted mankind for millennia.

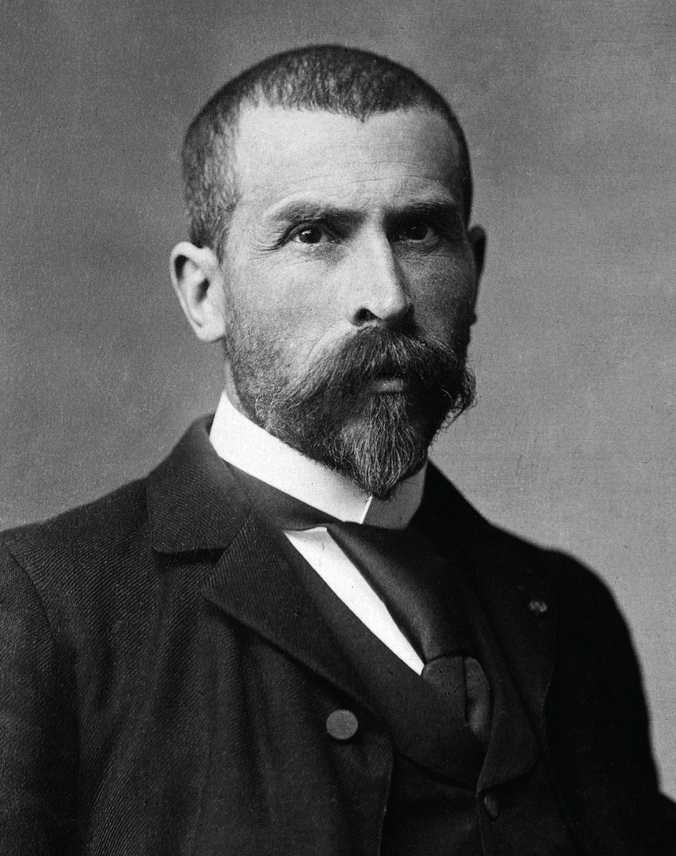

Shibasaburo Kitasato (1853–1931)

Shibasaburo Kitasato was born in Japan in 1853. As an outstanding medical student, he won the opportunity to study bacteriology in Germany under Robert Koch. During Kitasato’s six years in Berlin, he helped develop ways to treat tetanus and diphtheria.

In 1892, Kitasato returned to Japan where he continued to search for disease cures. When plague broke out in Hong Kong, the concerned Japanese government sent Kitasato to study it.

He arrived in Hong Kong on June 12, 1894, supported by two top-notch researchers and three experienced assistants. The British doctor in charge of Hong Kong’s main plague hospital, James Lowson, gave the Japanese team a room for their laboratory. They set up their equipment and got to work.

THE FRENCHMAN

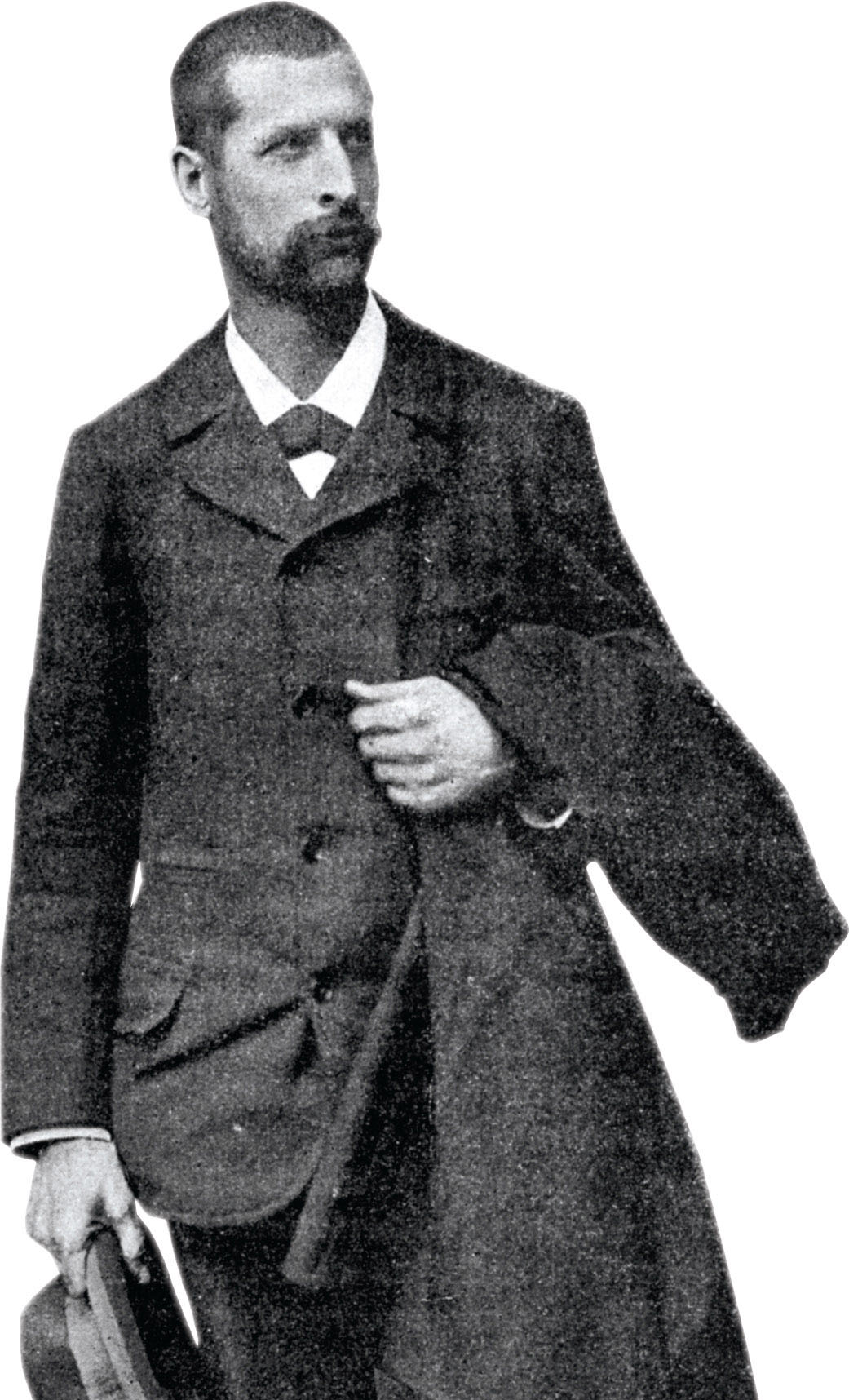

Alexandre Yersin arrived three days later. He was born in 1863 in Switzerland and grew up there. His mother was French, and Yersin adopted French citizenship in his midtwenties.

Although Yersin studied medicine, he never wanted to be a doctor with a private practice full of patients. In his opinion, “To ask for money for treating the sick is a bit like telling them, ‘Your money or your life.’”

Alexandre Yersin (1863–1943)

Instead, he took a job in Paris as a pathologist, preferring to spend his time in a laboratory. In 1886, a careless error changed the direction of his life.

While performing an autopsy on a person who had been bitten by a rabid dog, Yersin cut his hand and became infected with rabies. At one time, this would have been a death sentence. But the year before, Louis Pasteur and Émile Roux developed an effective anti-rabies treatment for humans. Yersin hurried to Pasteur’s Paris laboratory for help. Roux vaccinated him, saving his life.

The experience inspired the twenty-three-year-old Yersin. After his recovery, he left his pathology job to study bacteriology at the School of Medicine in Paris and with Robert Koch in Berlin. Later, Yersin worked with Roux at the Pasteur Institute in Paris, where they made advances in the treatment of diphtheria.

Alexandre Yersin wasn’t the typical medical researcher, however. He wanted to travel and explore French Indochina (today the countries of Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos). In 1890, he left Europe and took the position of physician on steamships in Southeast Asia.

When plague broke out in Hong Kong in 1894, Yersin knew he had to go there. He felt confident that he had the training and skill to tackle the frightening disease, just as he had diphtheria. “The first thing I shall have to do in the study of plague,” he wrote in his journal, “is to look for its microbe.” Hong Kong was the place to do it.

Émile Roux (1853–1933)

With help from his friends at the Pasteur Institute, Yersin convinced his government to send him to Hong Kong as part of the French colonial health service. In June 1894, he packed his bags and left Indochina on a cargo freighter.

THE RACE

Yersin landed in Hong Kong on Friday, June 15. He saw right away that he didn’t have Shibasaburo Kitasato’s connections. James Lowson refused to let Yersin near the corpses of hospital patients.

How could he do his research if he didn’t have access to a victim’s body? For Yersin, it was the essential first step: “More than anything, I would like to perform an autopsy.”

He suspected he’d find the plague microbes in the victim’s buboes, blood, and perhaps some organs. To identify these bacteria, Yersin would have to take samples and examine them under a microscope. He was aware that the Chinese were offended by autopsies. The only corpses he’d have a chance to cut open were those that the British made available, likely without permission from the deceased’s family.

Yersin found himself in a race, one the Japanese apparently were determined to win. Lowson was doing all he could to support Kitasato, whom he considered a more influential scientist than Yersin. That included obstructing Yersin’s research.

Without access to the main plague hospital’s facilities, Yersin worked from a straw hut nearby. His laboratory consisted of a microscope and glass slides, an autoclave to sterilize equipment, scalpels for cutting, and cages of guinea pigs and mice.

Yersin soon learned that he might have lost the race before he even started. The day before he arrived in Hong Kong, Kitasato had found microscopic organisms in plague corpses. He injected these microbes into test animals, which died within days. When Kitasato checked their bodies, he saw the same microorganisms.

Proudly, the Japanese team declared that these were plague bacteria. About a week later, on June 23, 1894, The Lancet officially announced Kitasato’s exciting discovery to the world.

It came with a steep price. Three of Kitasato’s fellow Japanese researchers fell ill with plague, and one of them died.

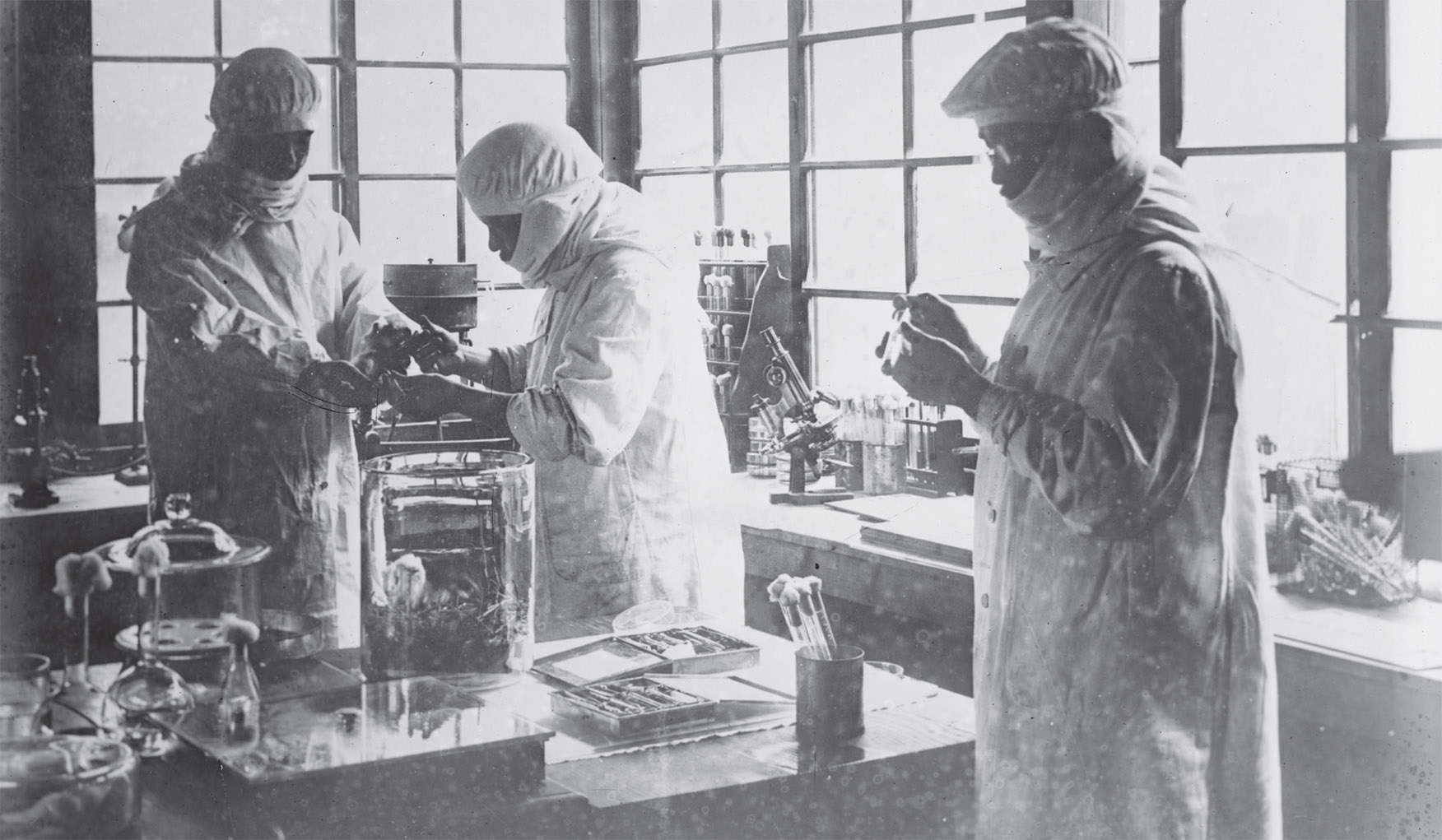

Japanese researchers inject plague bacteria into rats. This photograph was taken in Japan about twenty years after Kitasato’s work in Hong Kong.

Yersin was skeptical about Kitasato’s claim. After visiting the Japanese lab, he concluded that Kitasato was on the wrong track. In his report to the Pasteur Institute, he wrote: “I am surprised to see that they are not even examining the bubo; rather, they are minutely investigating the heart, the lungs, the liver, the spleen, etc.” Yersin felt sure that if the microbes were to be found, they would be in the buboes.

Kitasato’s announcement added to Yersin’s frustration. The Frenchman had already wasted five days trying to get access to a plague corpse. He was tired of dealing with Lowson and British red tape. On Wednesday, June 20, Yersin took action.

He walked over to the plague mortuary, an underground area outside the hospital where bodies were kept in cool temperatures before being buried. Two British sailors stood guard. They recognized the man who greeted them with friendly words when he passed by each day.

Images from Yersin’s 1894 scientific paper show his microscope view of small oval plague bacteria in various tissue samples: (1) from a human bubo; (2) from a dead rat; (3) from a broth culture; (4) from a mouse; (5) from the blood of a man dying of plague with only two tiny bacteria visible among the round blood cells.

Yersin slipped them some money. Would they let him go inside? The sailors didn’t hesitate. They unlocked the door and stepped aside.

Working quickly in the shadows, Yersin opened one of the caskets. He scanned the corpse for the telltale bubo. Pulling out his sharp scalpel, he cut away the swelling.

Yersin hurried back to his shack laboratory with the sample. Heart racing with anticipation, he prepared a slide with the bubo tissue and peered at it through the microscope lens.

Yersin poses in front of the straw hut he used as his Hong Kong laboratory in 1894.

As the view came into focus, he felt the thrill of the moment. “The specimen is full of microbes, all looking alike, with rounded ends,” he scribbled in his notebook. “This is without question the microbe of plague.”

Yersin cultured the oval bacteria, then injected them into his guinea pigs and mice. The next day he wrote: “My animals inoculated yesterday are dead and show the typical plague buboes.” When Yersin looked at samples of the animals’ buboes and organs under his microscope, he saw the same oval microbes.

They were not the same bacterium Kitasato described. “The microbe isolated first by the Japanese,” Yersin reported to the Pasteur Institute, “did not resemble mine in any way.”

Yersin named the plague microbe Bacterium pestis, and the Pasteur Institute in Paris announced his discovery on July 30, 1894.

The public announcement irked Lowson. In August, he sent a letter to Kitasato, who by then had made his triumphant return to Japan. “I salute you and hope that you will be able to prepare a new shell filled with Pest Bacilli,” wrote Lowson. “If you can at the same time kill a man called Yersin, for God’s sake do so. He has led us a dance in a way but … we have got the better of him.”

Lowson illustrated his note with a sketch of Yersin, making the Frenchman look like the devil.

The Yersin-Kitasato story didn’t end there. Both men were recognized for finding the plague bacterium, though Kitasato received credit for beating Yersin by six days. Many British and American medical books acknowledged Kitasato as the true discoverer of the microbe, while the French gave the nod to Yersin.

But as Yersin realized in June 1894, the descriptions by the two bacteriologists were different in significant ways. Other scientists eventually found flaws in Kitasato’s research. The bacterium he described does not cause plague. It causes pneumonia. Kitasato mistakenly incriminated the wrong microbe in his sample tissue from plague corpses.

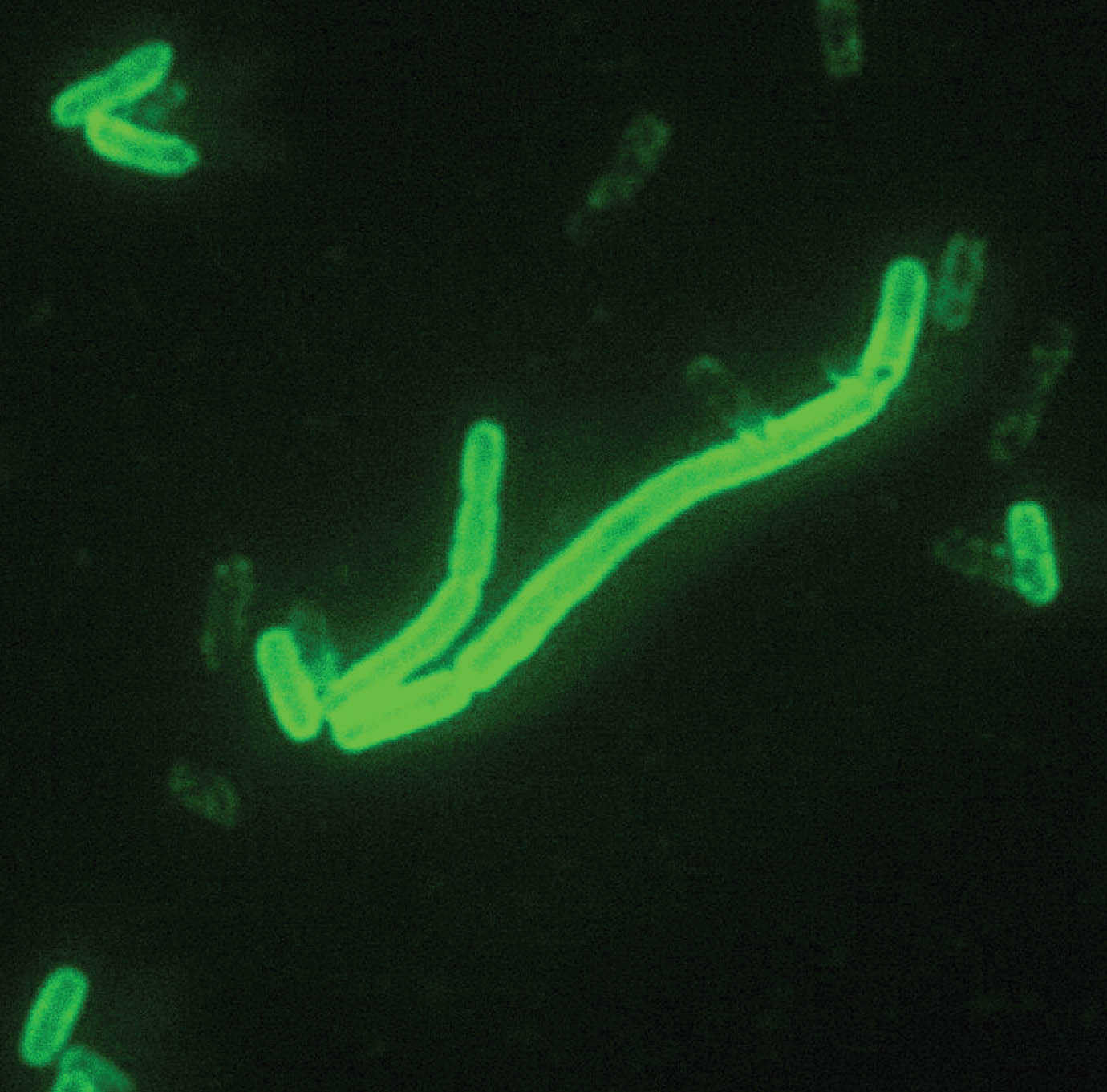

Several oval-shaped Yersinia pestis, highly magnified and stained to appear green

Yersin’s detailed description in June 1894 had been accurate. More than seventy years later, the microbe was finally renamed Yersinia pestis in his honor.

Finding the plague bacterium wasn’t enough for Yersin. He still had a hunch to investigate.

While walking around Hong Kong in June and July 1894, he noticed dead rats everywhere, even inside the plague hospital. Like Mary Niles, Yersin had heard the superstition about rat die-offs. What if it were true and plague killed these rats, too?

To find out, he collected rat corpses and took samples of their lymph nodes and blood. He examined the fluid under his microscope.

Amazing! There they were. The very same microbes he had seen in the bubo of the human plague victim.

Next, Yersin injected mice with these plague bacteria and placed the animals in a cage with healthy mice. The inoculated ones died. Within a few days, the rest died. When Yersin examined the dead animals’ tissues, he found plague bacteria in all of them.

His hunch was right. Plague killed the rats, and it killed the healthy mice, too. Yersin had made an important breakthrough. “Plague is therefore a contagious and transmissible disease,” he concluded. “It is probable that rats are the major vector in its propagation.”

How did rats pass the disease to each other and to humans? That remained a puzzle.

FIGHTING THE GERMS

The discovery of the plague microbe during the summer of 1894 was hailed worldwide as a triumph by science and modern medicine.

The top U.S. health official, Surgeon General of the Marine-Hospital Service Walter Wyman, said of the news: “All through the centuries … [plague] has been enveloped in darkness, and there has been the same groping after facts, the same unsuccessful search for the true cause, the same struggle in ignorance against its ravages. … [It is now] robbed of its terror by science.”

Doctors assumed that the bacteria spread from a victim’s breath, blood, feces, and bubo pus. Rats spread it, too—to each other and to humans—by contaminating water, buildings, and soil. Going barefoot, as many Chinese did, allowed germs on the contaminated ground to enter the body through tiny foot cuts. To the medical community, this explained why fewer Europeans than Asians developed plague.

Health officials saw no reason to change their approach to plague outbreaks. Destroy the germs. Isolate the sick. Quarantine those exposed.

Several more years would pass before plague fighters learned there was a better way.

Meanwhile, plague kept moving. Hong Kong was a busy port where British steamships collected and delivered passengers and cargo. The disease wouldn’t be confined there for long. Before anyone could stop it, plague found its way across the seas.

A Chinese sailboat and a British steamship in the Hong Kong harbor in 1902