QUARANTINE OUTRAGE

“It is unreasonable, unjust, and oppressive.”

—Judge William Morrow, 1900

The judge had stopped the inoculations and the travel restrictions. But city leaders couldn’t afford to abandon the anti-plague efforts. Several states threatened to bar passengers and cargo coming from San Francisco and California. The city had to show that plague was under control.

On May 28, 1900, the San Francisco Board of Supervisors declared that plague existed, putting the city on firmer legal ground than it had been with the Board of Health’s May 18 declaration. The Supervisors voted to authorize a quarantine “necessary to prevent the spreading of contagious or infectious diseases” in the city.

The next day, the second quarantine of Chinatown began. More than 150 police officers guarded the roped-off perimeter. This time, health officials added barbed-wire barricades on some streets.

Inspectors renewed their search for plague victims, with the intention of moving them into isolation. The health department resumed the Chinatown cleanup. The district was “a menace to public health,” the city’s chief sanitary inspector proclaimed. He blamed the dirty conditions on the “aliens, who differ in their customs, habits and ideas of sanitation from those approved by modern sanitarians.”

Ropes and barbed wire block off Chinatown during the second quarantine in late May 1900.

Kinyoun was concerned that the city was missing one key element in their campaign: rat-killing. The Service considered rats “without doubt … the most active agents of spreading [bubonic plague].” The cleanup would help lower the rat population because the rodents found food and shelter in the filth. But to stop the plague outbreak, Kinyoun told the Board of Health, the city had to eradicate them.

On Angel Island, he said, the Service used sulfur dioxide gas to kill rodents aboard incoming ships, and the city should use it, too. Kinyoun also recommended traps and poison bait, such as fish stuffed with arsenic.

Acting on his suggestion, the Boards of Health and Public Works began a rat destruction campaign in Chinatown and nearby neighborhoods. Unfortunately, the city lacked the money to carry on the kind of extensive rat-killing plan that Kinyoun advised.

NO PLAGUE HERE

Among Chinatown residents, the second quarantine was even less popular than the first. Consul Ho Yow charged that health authorities had put people living inside the cordon at risk. “Do they want to imprison the residents of the entire district and force them to contract the plague?”

The San Francisco Call pointed out that the blockade wouldn’t stop an epidemic from spreading—if there actually was one. “No white man can enter, but any white man can come out; no Chinaman can come out, but any Chinaman can enter.” People stood on either side of the barrier, the paper said, talking and passing packages back and forth. “That is the sort of thing which is called ‘quarantining against the bubonic plague.’”

The cordon was supposed to prevent plague’s spread from people inside Chinatown to other San Franciscans. Yet it didn’t stop these Chinese and white men from carrying on a face-to-face conversation across the rope.

The day the Call’s critical article appeared, Dang Hong died in a coffin shop on Pacific Street in Chinatown. His lymph nodes were filled with plague bacteria.

During the next fourteen days, 2 more men died of plague. By early June, the outbreak had claimed a total of 12 lives in Chinatown. Kinyoun wondered if other victims had been hidden from health officials or smuggled out of the city.

Once again, San Francisco’s Chinese population and most of the press refused to believe that the latest deaths were from plague. Newspapers quoted physicians who said that nobody had yet died of the disease. Kinyoun heard rumors that some newspapers were paying for medical opinions that refuted his lab-test results and the health department’s diagnoses.

California’s governor, Henry T. Gage, publicly questioned plague’s existence, too. He objected to meddling by the Marine-Hospital Service into the affairs of the state. And he didn’t like the actions of the San Francisco Board of Health, either.

In a telegram to the U.S. secretary of state, Gage declared, “Bubonic plague does not exist and has not existed within the State of California.” He claimed to have talked to plague experts who witnessed the disease in India, and they assured him that the dead were not plague victims.

BURN IT DOWN!

But as more deaths occurred, other people became convinced that the city had to do something about Chinatown—immediately. If there wasn’t plague now, other diseases certainly could breed there. Such a foul slum, right in the heart of the city, was a disgrace. It was bad for business if San Francisco was considered a dirty place, harboring such “appalling disgustfulness.” A member of the state board of health announced, “I would advocate the complete destruction of Chinatown by fire.”

A man delivers supplies into Chinatown by pushing them under the cordon rope.

San Francisco’s Chinese newspapers reported on the calls to level Chinatown and on the city’s plans to set up detention centers for everyone exposed to plague. Anxiety rose in the neighborhood.

On June 5, the Six Companies threatened that if anyone was removed from Chinatown, the Chinese would resist by force. Lawyers for the group filed a lawsuit on behalf of Jew Ho, who owned a grocery store on the edge of Chinatown, and the thousands of people caught inside the cordon.

The suit charged that the quarantine discriminated against Jew. The barricade curved to include his grocery but not neighboring white-owned businesses. None of his customers from outside the cordon could reach his store. The quarantine was unnecessary since there “never has been any case of bubonic plague.”

Ten days later, Judge Morrow announced his decision to a crowded courtroom of lawyers, press, and spectators. The quarantine, he said, “is made to operate against the Chinese population only, and the reason given for it is that the Chinese may communicate the disease from one to the other.” That makes it discrimination against Asians. “It is unreasonable, unjust, and oppressive,” Morrow continued, “and therefore contrary to the laws limiting the police powers of the State and municipality.”

He ordered Chinatown’s cordon removed. The Board of Health could not quarantine an entire section of the city. Morrow allowed health officials to quarantine and disinfect only individual houses where they found infected people.

By midafternoon, police officers took down the ropes and barbed wire. After nearly three weeks, the second quarantine of Chinatown was over.

Shopkeepers opened their stores. Delivery wagons resumed their rounds in the neighborhood. People once again appeared on the streets, hurrying in and out of Chinatown and trying to return to their normal routine. Many had been afraid that the health department would yank them from their homes and burn their community to the ground. Judge Morrow erased their fears.

BACK TO COURT

The quarantine was over, but Kinyoun’s problems were not. He still had a duty to prevent plague from spreading out of California. Morrow’s ruling concerned travel within the state. Kinyoun believed the Service had the legal power to forbid people from leaving for other states if they lacked official proof that they were plague free. Kinyoun refused to back down “unless ordered by Secretary of Treasury or Surgeon-General.”

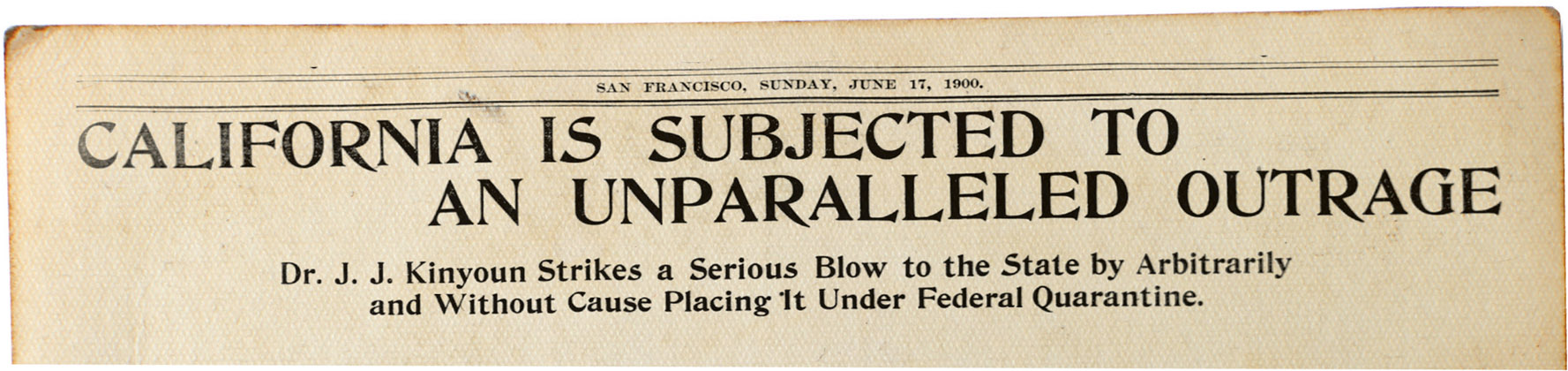

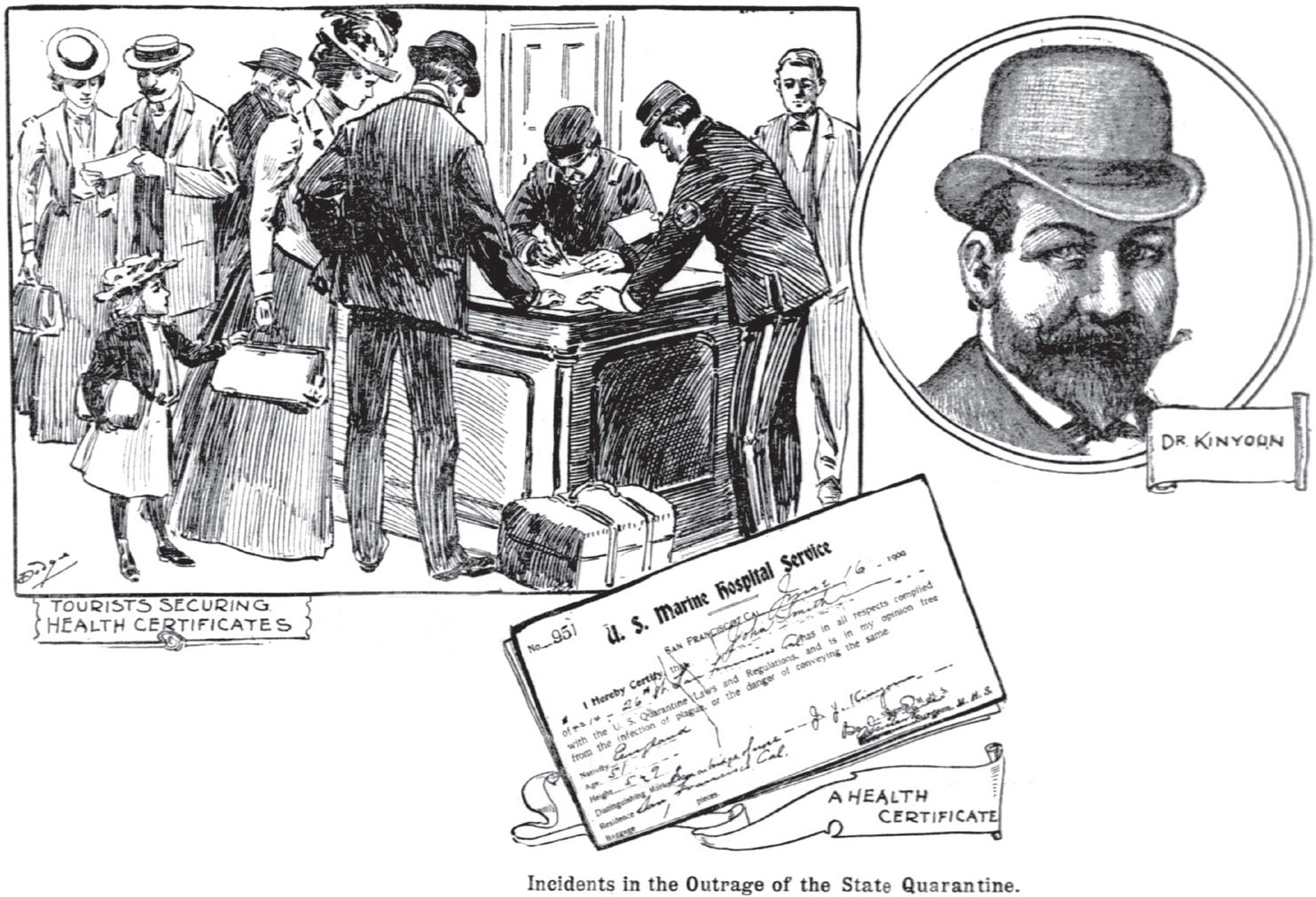

The headlines and cartoons from the San Francisco Call, June 17, 1900, reveal the newspaper’s critical opinion of Kinyoun’s travel ban.

On June 16, lawyers for Wong Wai, the merchant who brought the first court case in May, went to Judge Morrow again. Wong had business in Eureka, California, a coastal city north of San Francisco, and he had tried to buy a steamship ticket there. His lawyers charged that Kinyoun would not let Wong board the ship without proof that he’d received the Haffkine vaccine. Kinyoun, they said, was ignoring the judge’s May 28 ruling that allowed travel by Asians to other parts of California.

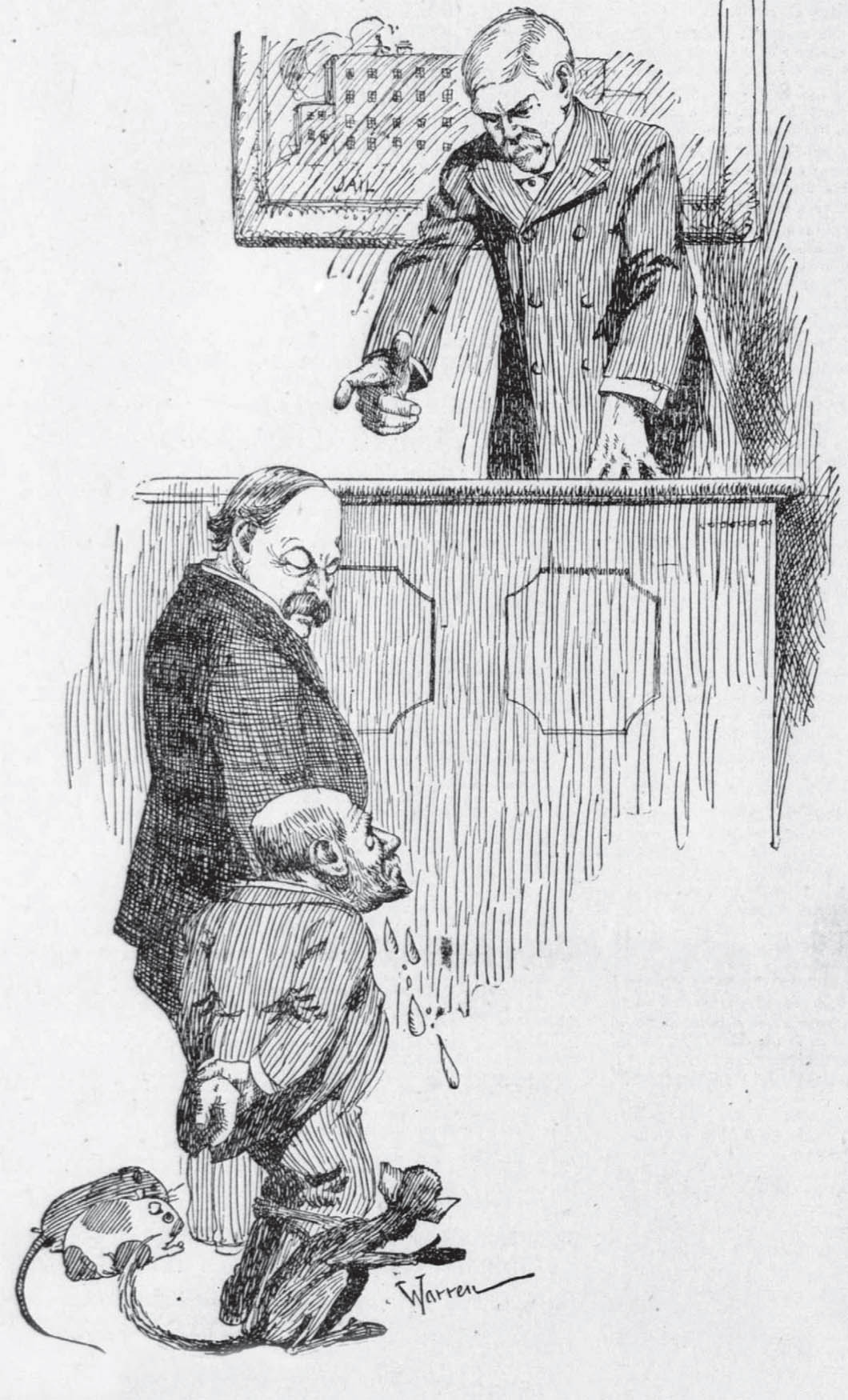

Judge Morrow ordered Kinyoun to appear in court to answer the charges. Kinyoun worried that the judge might send him to jail for contempt of court, even though he was carrying out instructions by his superiors in Washington.

At the hearing, Kinyoun testified that his concern was only with travel from San Francisco to other states. He told steamship companies they could sell tickets for in-state travel without health certificates. He denied ever meeting Wong Wai or stopping him from buying a ticket to Eureka.

The legal proceedings didn’t go well for Kinyoun. The court refused to consider evidence he provided. The government attorney, who was supposed to provide his defense, was incompetent. Kinyoun felt abandoned by Wyman, who wasn’t doing enough to help. Everyone involved seemed to be against him.

The stress of the past months had taken its toll on his health, and he suffered from severe stomach pains. These legal troubles made things worse.

A HATED MAN

Kinyoun had powerful enemies: Governor Gage and his political allies, the press, businesses, and much of the public.

Gage wanted Kinyoun’s head. The governor complained that plague rumors, ill-advised quarantines, and travel restrictions hurt California’s business and trade. Gage suggested that the bacteria, which Kinyoun claimed came from the victims’ bodies, were really plague cultures imported from other countries. A newspaper commenting on the governor’s accusations said, “Perhaps some inadvertently got loose in Kinyoun’s bubonic pig pen.”

In a cartoon from the San Francisco Call, June 19, 1900, Kinyoun sweats as he appears with his lawyer before Judge Morrow. His test animals gather at his feet. The Call used the rat, guinea pig, and monkey to remind readers that plague in the city was a fake.

The San Francisco newspapers called for “the removal from office of this incompetent and mischievous official.” They referred to the cordon as the Kinyoun quarantine. “The harm which a pig-headed mischief-maker can do when intrusted with official power is now clear to us and we must get rid of Kinyounism by getting rid of Kinyoun.”

Kinyoun heard that someone placed a $7,000 bounty on his life, and he started carrying a gun for protection.

Members of the Republican Party warned President McKinley that the plague controversy could hurt his chances in California during the November presidential election. The president and Wyman wanted to avoid a fight that could have serious political repercussions. They decided to ease the tensions in California.

On June 18, Wyman sent a telegram to Kinyoun: “Withdraw all inspections until further orders.” The federal restrictions against travel from San Francisco would end.

Kinyoun was afraid this wouldn’t be enough to satisfy Judge Morrow and save him from jail.

On the morning of July 3, he stood before the judge, anxiously waiting to hear the verdict.

Morrow read his decision: “Kinyoun did not violate the order of the court in restraining [Wong Wai] … from departing from the city and county of San Francisco for the port of Eureka.”

Kinyoun could hardly believe it. He was off the hook.

But the people of San Francisco didn’t care what the judge said. They hated Joseph Kinyoun. There was no plague, and he had overreacted. Thanks to him, the rest of the country had shunned San Francisco over nothing. They wanted Kinyoun, the mayor, and the Board of Health gone.

Kinyoun realized that he had become the scapegoat in the fight over plague’s existence in San Francisco. He knew he had failed at playing politics. His opponents criticized and blocked everything he did to control the threat of plague. He wrote his uncle, “I am at war with everybody out here.”

![]()

On July 5, two days after the judge cleared Kinyoun of contempt, Lee Wing Tong died in the city hospital. His doctor said he suffered from typhoid fever.

The diagnosis was wrong. An autopsy revealed that the man had a large groin bubo and swollen lymph glands under his arm. Lab tests proved that his body contained plague bacteria.

The dying wasn’t over.