TELEVISION, ADVERTISING AND CANADIAN ELECTIONS

Jean Crête

INTRODUCTION

ELECTION PROPAGANDA IS an integral part of the democratic process. It promotes discussion of ideas that govern society and an appreciation of the people who embody these ideas. The conditions and constraints of propaganda are themselves the subject of discussion, if not controversy. This is nothing new, even though public authorities have intervened in recent years in the way propaganda is distributed. This intervention is explained particularly by the fact that the state governs one of the main election propaganda vehicles: television. Today, it would be unthinkable to study an election campaign without looking at party advertising. This is a relatively new attitude for political analysts, however. For example, the major study on the electoral behaviour of Canadians, Political Choice in Canada, mentions election advertising only in passing (Clarke et al. 1979). Although studies published after Political Choice in Canada provide a more detailed description of election advertising, they do not evaluate the effect of such advertising on voting behaviour (Fletcher 1981b; Monière 1988). Election advertising, especially televised advertising, eats up a large part of the budget and energy of political parties during election campaigns. Canadian election studies are neither atypical nor leaders in this field.

For political party strategists, advertising is only one of many ways to get a message to all or part of the electorate. Newscasts and public affairs programs are an even more important means of propaganda. Unlike advertising, newscasts permit partisan organizations no control over many aspects of production and broadcasting. Because the media, and particularly television, face many constraints, partisan organizations can always arrange to participate effectively by offering to cooperate, at least for producing the programs in question. During the televised leaders debates, for example, party strategists are even more important than during newscasts, because their cooperation is absolutely necessary for the program to be produced and broadcast.

In this study, I review literature on the relationship between televised election advertising and media coverage of parties during election campaigns, including leaders debates. I also look at the characteristics of the electorate.

Importance of Election Campaigns

In a country where electoral volatility is high and voters do not have strong party loyalties, election campaigns are important. When party loyalty is weak, more votes can be lost or gained. When The American Voter (Campbell et al. 1964) was published almost 30 years ago, most voters identified with one party, which explained voting patterns. Today, the role of the volatile voter is vital. We can no longer assume that people will vote as their parents did, or even as they voted in the last election.

According to American electoral sociology of the 1950s, most voters had made up their minds before the election campaigns actually began. For political parties, therefore, the main purpose of election campaigns was to retain established support by strengthening convictions and motivating their supporters to go out and vote. When voter loyalty declines, however, it is easier to make converts. In the 1974 Canadian general election, for example, an estimated 45 percent of voters made their choice during the campaign itself (Clarke et al. 1979, 276). If voters no longer rely on their affiliation with any particular party when voting, however, they must use other criteria to make a decision. These new criteria may include knowledge of the events and issues at hand, as well as the positions of candidates and parties on these issues. American sociology leads us to believe that voting patterns are now determined by the issues at hand and the characteristics of party leaders.

We also know that television has changed the way people use their time, becoming a substitute for many activities. This substitution is not the same in all segments of society (Comstock 1982). Because television is the most popular medium, the relationship between exposure to television and electoral behaviour is important.

To approach this issue, I refer throughout the study to a number of hypotheses found in election studies. As required, I refer to experimental studies, as they highlight the nature of the relationships between variables better than real-situation studies where the contaminating effects of other elements cannot be controlled. The major drawback of experimental studies, however, is that they provide no information on the prevalence of the phenomenon studied in a real situation.

In this study I refer only to hypotheses that are directly relevant to election campaigns. Although these hypotheses do not cover all communication processes relevant to political persuasion, it is important to begin by unfolding the entire map that, at least implicitly, guides our search for hypotheses. In his writings on public communication, McGuire (1989) presents this map in the form of the classical persuasion model’s input–output matrix (figure 1.1).

The model’s matrix includes these input variables: the source of communication, the message itself, the channel through which the message moves, the recipient of the message and the goal of the communication. The other axis of the matrix consists of output variables ordered on a unidimensional axis that assumes pure rationality. Although no communication theory actually states this specific model, the model is used as a checklist by most authors. In the following pages, I do not necessarily treat these output variables in the order presented in figure 1.1. For example, given that a generation of voters does not suddenly appear in a given election, but is the product of a slow socialization process beginning in early childhood, it is illusory to think that these voters approach an election campaign without baggage. As we will see, it may be hypothesized that interest (output variable 3) in the election campaign is not necessarily the product of exposure (output variable 1) to election messages; on the contrary, interest could well be the factor that leads to exposure to the media.

In this study, I examine only some of the 60 matrix cells, reflecting the state of knowledge in the field of election communications. In the first part of the study, I deal with the message and channel in the context of media coverage of political parties and candidates during an election period. In the second part, I discuss knowledge of politics (output variable 4) and interest (output variable 3). In the third section, I examine some studies on the relationship between the media and the information that is stored (variable 7) and reactivated (variable 8) to reach a decision. The final section deals more explicitly with the decision and behaviour (variables 9 and 10). In the process, I outline some of the hypotheses on election advertising and draw some practical conclusions from this review of the literature.

THE MEDIA

Media Coverage of Parties

News broadcasts are the first way for political parties to reach voters. In most liberal democratic countries, election campaign observers have noted that political parties have focused much of their effort on obtaining favourable television coverage, since this is the most popular medium. In an election campaign strategy, television programs, especially newscasts and public affairs programs, are but one way to reach the electorate. It is therefore logical for analysts to check broadcasts on television regularly and, because newscasts are a preferred time to broadcast political information, to note the proportion of the news that was devoted to each political party.

Certain principles govern television networks when producing news broadcasts. Election campaigns put two in particular to the test (Seaton and Pimlott 1987, 133). First, there is the principle of balance, which has no direct bearing in the print media. In practice, balance means giving each of the political parties a specified portion of air time. A television network, for example, will follow the leaders of the three major federal political parties, regardless of their relative news-worthiness. The second principle is objectivity. By objectivity journalists mean a mirror of the real world. However, this mirror can only “reflect” certain events and not others, seeing and presenting them from a specific angle.

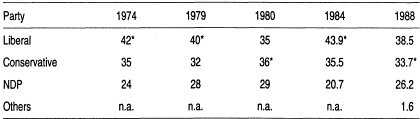

Based on objectivity, one assumes that the party of the incumbent government would be in the news more often than the other parties. To support this hypothesis I reason that the party in power must give an account of its mandate and is more likely to have “stars” (ministers) whose actions and statements are newsworthy even outside election periods. Refuting this hypothesis does not necessarily imply a lack of objectivity, given the other related postulates. The hypothesis was accurate in a study of the print media during most Quebec provincial election campaigns (Crête 1984), but not so in the case of television during the 1987 British elections (Axford and Madgwick 1989, 149, table 14.1). What about Canadian federal elections? The relative importance accorded by television evening newscasts to each party in elections since 1974 is compared in table 1.1.

Table 1.1

Relative importance granted to each party in television news coverage of election campaigns, 1974–88

(percentages)

Sources: 1974: Fletcher (1981a, 305, table 10–7); 1979 and 1980: Fletcher (1981b, 147, table 6); 1984: Estimated from Wagenberg et al. (1988, 121, table 1); 1988: Based on 1988 Canadian Election Study.

*Designates incumbent government.

n.a. = not available.

Despite the variety of samples and indicators used in these studies, the amount of attention given to the various parties is relatively stable. I therefore reject the assumption that the incumbent government always starts with an advantage. In fact, the figures in the table indicate that when the incumbent is the Liberal party it has an advantage, whereas when the incumbent is the Progressive Conservative party it rarely has an advantage. This “advantage” is based on the time devoted to the various parties in network newscasts, not on the content of the news.

If we start with the premise that the networks are influenced more by the principle of balance, we assume that air time is distributed according to each party’s relative popularity with the electorate. For example, using a program sampling taken at the beginning of 1974, Winn (1976, 135) showed that the CBC allotted air time to political parties based on their numbers in the House of Commons. Similarly, Fletcher (1988, 167) showed that during the 1980 and 1984 election campaigns the attention given to political parties during televised newscasts was similar to the division of free air time among the parties. This formula is not based on the popularity of the parties at election time, but rather on their popularity during the previous election.

Although there may be reservations about how the “coverage” variable in table 1.1 is measured, we can try to evaluate the overall bias resulting from the principle of balance. In correlating the importance newscasts gave to each party in election campaigns between 1974 and 1988 (see table 1.1) with the percentages of votes these parties won, we obtain a correlation coefficient of 0.68. If we use the results of the previous rather than the current election, the coefficient is 0.78. In short, when predicting the amount of coverage a political party will receive during televised newscasts, predictions based on the percentage of the vote obtained during the last election are more accurate than those based on current popularity. However, the belief that the news should reflect the present more than the past is itself biased. Because the correlation between the distribution of current news air time and the previous election results is not perfect, we can assume that other factors come into play.

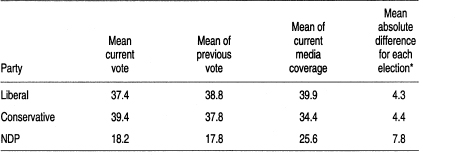

On average, the difference between the percentage of the vote at the previous election and the percentage of televised news air time is not very wide for the Liberal and Conservative parties, as table 1.2 shows. Moreover, if we calculate the absolute average spread between the previous vote and coverage, we notice that the spread, or errors, are equal between the two parties. Most of the errors come from coverage of the 1988 election campaign. During the 1984 election, the Conservative party won 50 percent of the vote and 74 percent of the seats. If the votes won during the previous election had been the only determining factor in the balance principle, the Conservative party would have had as much air time as all the other parties combined during the 1988 campaign. The distribution of newscast air time during an election, therefore, seems to be based largely, although not solely, on past performance. Past performance is also constrained by the number of parties recognized in the House of Commons. The New Democratic Party (NDP) benefits the most from the balance principle because it gets about 30 percent more air time than its election results warrant. The very small parties, those without enough elected representatives to be recognized as parties in the House of Commons, receive approximately 1.5 percent of newscast air time.

Table 1.2

Relative attention paid to the major parties by television networks during election campaigns, 1974–88, compared with election results

(percentages)

Sources: Fletcher (1981a, 1981b); Wagenberg et al. (1988); Canada, Elections Canada, various years.

*Mean absolute difference is computed as follows: percentage of coverage for a party at an election minus the percentage of votes for this party at the previous election. This is averaged over elections, ignoring the signs (+, -).

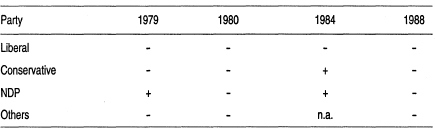

Assessment of Parties and Candidates

According to content analyses of national network news programs during federal election campaigns since 1974, the projected image of both the Liberal and the Progressive Conservative parties is more often negative than positive (table 1.3). The NDP is less often on the news, and the image is more positive than for the other two larger parties. Although data come mostly from the CBC, an examination of the other networks would likely produce the same results. In fact, a comparison of networks during the 1979 elections (Fletcher 1981c, table 10-8) shows that the results are the same, regardless of the channel studied.

Table 1.3

Overall positive and negative orientation of election news on television

Sources: 1979: Fletcher (1981b, 148, table 7); 1980: Soderlund et al. (1984, 70, table 3-9); 1984: Wagenberg et al. (1988, 123, table 3); 1988: Based on 1988 Canadian Election Study.

Note: The data for 1979, 1980 and 1988 were taken from CBC news bulletins, while the 1984 data are a combination of CBC, SRC, CTV, TVA and Global data.

The often negative impression of parties presented in the news does not necessarily indicate that the networks are biased. In fact, most of the news items are neutral. Also, most negatively interpreted items are merely reports of unfortunate events for a party, such as an opinion poll showing a particular party losing ground or a party member being accused of wrongdoing. I suspect, however, that the media view partisan events with a critical eye, regardless of the party involved.

The image in the broadcast media is no different from the public’s image of politicians: “In general, the parties and politicians who run the political system are regarded with distaste by most of the public” (Clarke et al. 1979, 31). Kornberg and Wolfe (1980), who studied coverage of parliamentary proceedings by daily newspapers and the public’s regard for Parliament, suggest that the public’s low confidence in politicians stems from journalists’ reports on parliamentary proceedings. This is all the more important because we generally expect the public to have a more positive attitude toward public figures (Lau et al. 1979).

Issues, Local Candidates and Party Leaders

Before examining the various studies (predominantly American) on the relationship between media coverage, advertising and the electorate, it is appropriate to note a few features of election coverage by the Canadian media. Do the Canadian media give the public information on the issues and the candidates, or do they present the election more as a horse race?

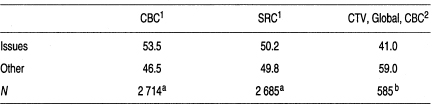

Data on the 1988 federal election show that about half the information broadcast on television dealt with issues (table 1.4), contrary to what we might expect from the American example.

In Canada, as in the United States and other industrialized countries, television and the concentration of ownership of the daily press have “nationalized” politics.1 Network news items are chosen for their interest to viewers across the entire network. It is not surprising, therefore, that party leaders and central organizations are given more space than local candidates and constituency associations. The space occupied by each of the various players in newscasts is suggested in table 1.5.

Local candidates have more space on Radio-Canada newscasts than on the CBC news, reflecting the more regional character of the Radio-Canada network in Quebec. It also shows the distinct character of federal election campaigns in Quebec. Even when identical themes are covered by both the CBC and Radio-Canada, for linguistic reasons there are often different spokespersons.

Canadian election rules, political culture and media restrictions imposed internally or externally set the Canadian situation apart from the American case. The differences cited above should be kept in mind in applying proposals from the American experience to the Canadian situation.

Table 1.4

Election news devoted to issues in 1988

(percentage of time)

Sources:

1Based on 1988 Canadian Election Study.

2Taken from Frizzell et al. (1989, 84).

aThe units are statements.

bThe units are news items.

Table 1.5

Election news time devoted to various players during the 1988 federal election

(percentage of time)

Players | CBC National | SRC |

Leaders | 59.7 | 48.7 |

Parties | 15.1 | 14.5 |

Candidates | 7.5 | 14.7 |

Other players | 17.1 | 22.1 |

Source: Based on 1988 Canadian Election Study.

Note: Percentages may not add up to 100.0 because of rounding.

KNOWLEDGE OF AND INTEREST IN POLITICS

Knowledge of Politics

In the United States, political knowledge is usually defined as the ability to remember the names and personal characteristics of candidates, to identify election issues and campaign developments, and to recognize the connection between candidates and issues. In rating the effectiveness of the media, the criterion of voter information gain is primary. As Chaffee notes (1977, 215), this criterion is usually ignored, since researchers find it of little interest.

What do we know about the effectiveness of the media in disseminating political information that the public can use, for example, in exercising its democratic right to elect governments or decide on specific issues during referendums? Several studies on voting patterns have addressed the impact of mass media campaigns on obtaining information.

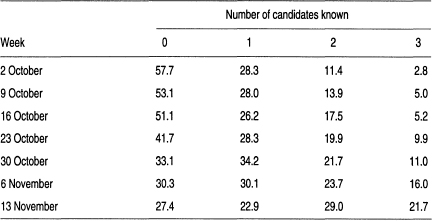

The reader can have an idea of the level of voter knowledge in Canada by consulting the data in table 1.6.

Table 1.6

Knowledge of local candidates, 1988 federal election campaign

(percentages)

Source: Based on 1988 Canadian Election Study.

Note: The knowledge index is the number of local candidates that the interviewees could identify in response to the following questions: Do you know the name of the Conservative candidate in your riding? And the name of the Liberal candidate in your riding? And the name of the NDP candidate in your riding?

Table 1.6 presents an index of the degree of knowledge of candidates’ names in local ridings. In the week when the 1988 election campaign began, close to three voters in five (57.7 percent) could not name a single candidate in their riding. However, all the candidates had not yet been chosen by that date. In the week of the leaders debate and the launching of election advertising, a little over four voters in ten could not name a single candidate. By election week, only 27 percent of voters were unable to name at least one candidate. The percentage of those who could name three candidates increased considerably during the campaign.

Overall results confirm that there is a connection between media exposure, especially the print media, and knowledge of the facts related to election campaigns (Berelson et al. 1954; Trenaman and McQuail 1961; Katz and Feldman 1962; Blumler and McQuail 1968). It has been more difficult, however, to show that media exposure increases the level of political knowledge. Nevertheless, some researchers have tackled this problem.

The News

In an experimental study in the United States, Behr (1985) was able to show that television can have decisive effects. In this experiment, people watched television for one week in an area specially prepared by the experimenter. The subjects agreed not to watch television at home. The experimenter divided them randomly into two groups. The experimental group watched local newscasts that included profiles of the candidates in a House of Representatives election; the control group watched the same newscasts, except that any information pertaining to the election or the candidates was deleted. One day after the last viewing session, only 56 percent of those in the control group were able to match candidates with their political party, whereas almost everyone in the experimental group could. This was an experimental study, that is, a study in which the contextual variables were controlled by the random distribution of the subjects. Would results be the same if the controls were relaxed? A British study indicates otherwise.

Three opinion polls were conducted during the 1987 election campaign in Great Britain: one poll done two weeks before the election, another done one or two days before and a third, five or six days after the election. The polls showed that the public’s knowledge of certain issues had not increased appreciably. The test was conducted using the election platforms of the three major parties. The researchers identified ten clear and unambiguous political proposals and asked the people interviewed to attribute each proposal to one of the three parties. Two weeks before the election, 42 percent of the interviewees were able to match at least seven out of ten proposals correctly; two days before the election the proportion was 47 percent; one week after the election, the percentage had fallen to 44 percent (McGregor et al. 1989, 183). If we take into account a margin of error in the sampling, we might conclude that there was no significant change from one group to the other. Throughout the experiment, the percentage of respondents who were unable to match more than three proposals to the correct party remained stable. Also, more than half the respondents who had seen something about the election on television were able to match seven proposals correctly, while only one-fifth of those who had not see any televised news reports were that successful (ibid.). Although we can conclude that people who could match proposals with parties are also those who watch programs dealing with the election, we cannot conclude that the number of people who know the positions of the various parties increases during election campaigns.

During this election campaign, an increasingly greater number of television viewers believed that television placed too much importance on the election (McGregor et al. 1989, 176). Compared with the number of viewers before the campaign, the main BBC television newscast lost 25 percent of its viewers, while the private channel ITV lost 11 percent (Blumler et al. 1989, 171). This loss of audience may explain why the number of informed people remains unchanged. In the United States, it has been noted that exposure to television programs dealing with presidential election campaigns depends on whether the election is a close race (Danowski and Ruchinskas 1983). In a tight race, voters follow programs dealing with the election more attentively. Apparently, the 1987 British general election was not very interesting to voters, given that the change in the incumbent party’s percentage of votes was the lowest since 1950 (Kavanagh 1989, table 1.1).

Advertising

At the beginning of the 1970s, Atkin and his colleagues (Atkin et al. 1973; Atkin and Heald 1976) and Patterson and McClure (1974, 1976) focused their studies on election advertising and showed that such advertising increases voter knowledge of the issues and the candidates.

Patterson and McClure (1974, 1976) reported that three-quarters of voters who remembered having seen political ads were able to identify the message of the ads. Also, voters who had a great deal of exposure to television were more likely to identify candidates’ positions correctly from a list of 10 issues presented in the political ads. On average, among informed viewers, there was a 32 percent shift toward correct identification, while this percentage was 24 percent among less-informed viewers. Atkin et al. (1973) pointed out that voters obtain a great deal of information on issues and candidates through political ads.

Proposition: | Election advertising increases voters’ knowledge of issues and candidates. |

Several studies have identified the conditions that make it easier to acquire political knowledge. Patterson and McClure (1974) showed that election advertising had a greater impact on people who rarely watch television news or read newspapers. Although this conclusion seems at first glance to be the most logical one, it is not completely corroborated by the data, as shown in table 1.7.

Table 1.7 provides data on the degree of knowledge, or rather ignorance, of citizens according to their exposure to the media and advertising during the 1988 federal election campaign. The media exposure index is the number of days per week the interviewee reports having read a newspaper, added to the number of days that person reported having listened to the news on television. A person who listened to the news and read the paper every day obtained the maximum score of 14. On the opposite end of the scale, the person who read no papers and listened to no televised news obtained a score of zero. From the table, it is apparent that the greater the exposure to information sources, the higher the level of knowledge. For example, among people with no exposure to these information sources and who did not see election advertising on television, 70 percent could not name a single candidate in their riding; at the other end of the spectrum – that is, among those who were exposed daily to the media and who saw election advertising – the percentage of those who did not know the candidates fell to 24.

The information in table 1.7 leads to the conclusion that exposure to election advertising substantially increases people’s knowledge of the candidates. Thus, the percentage of people who did not know the candidates among those who did not read newspapers and did not listen to televised news dropped from 70 to 63 percent if they saw election advertising. Unlike Patterson and McClure (1974), however, we cannot state that the greatest effect was among people who had little exposure to the media. In fact, if we looked only at people who were more interested in the media (index = 14) and those with no interest (index = 0), we would reach the opposite conclusion. In two different studies, Atkin and his colleagues (Atkin et al. 1973; Atkin and Heald 1976) also showed that voters who pay a great deal of attention to ads or who seek out information are more likely to increase their level of knowledge through election advertising than people who hear the advertising by accident.

Table 1.7

Exposure to the media and election advertising, and degree of knowledge

(percentages)

Percentage who could not name a single candidate | ||

Degree of exposure to the media* | Not exposed to advertising | Exposed to advertising |

0 | 70 | 63 |

1 | 62 | 50 |

2 | 65 | 61 |

3 | 61 | 41 |

4 | 46 | 48 |

5 | 46 | 46 |

6 | 41 | 35 |

7 | 51 | 41 |

8 | 44 | 37 |

9 | 47 | 29 |

10 | 50 | 29 |

11 | 39 | 28 |

12 | 33 | 30 |

13 | 23 | 17 |

14 | 36 | 24 |

Source: Based on 1988 Canadian Election Study.

*Number of days per week interviewee reported having read a newspaper, added to number of days that person reported having listened to news on television.

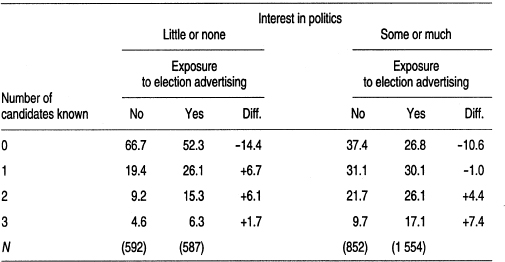

Although we do not have information on the accidental or voluntary nature of exposure to election advertising in the study of the 1988 federal election campaign in Canada, it is reasonable to think that people who are interested or very interested in politics are more likely to retain more of the election advertising than those who have little or no interest in politics. Table 1.8 relates data on the level of knowledge of Canadian citizens during the 1988 election to the degree of interest in politics. It shows that exposure to advertising is associated with an increased level of knowledge, regardless of the level of interest in politics. However, the deduction we made on the relationship between interest in politics and gain in information is not supported by the data. Our data are but indirect measures of the concepts used by Atkin and his colleagues (Atkin et al. 1973; Atkin and Heald 1976).

Table 1.8

Knowledge of candidates and exposure to election advertising, controlling for interest in politics

(percentages)

Source: Based on 1988 Canadian Election Study.

Note: Percentages may not add up to 100.0 because of rounding.

Proposition: | Exposure to campaign advertising and interest in politics are correlated. |

Channels and Destinations

The study by Hofstetter and his colleagues (1978, 568) gives us a good idea of the relative values of the various means of communication as sources of political information (table 1.9). Reading newspapers has had the greatest impact on the level of information by far. Radio and network television news rank second. The combination of local television news, discussions and commercials ranks third. The impact of newspapers, television news, political ads and discussions is greater with people who are less politically committed.

Proposition: | Election advertising is a major source of information for voters. |

Proposition: | The less politically aware the voter, the more important election advertising becomes. |

Table 1.9

Relative importance of various media as sources of political information

Sources of exposure to political information | (Beta) |

Television (total) | -0.08 |

Short advertising (spots) | 0.06 |

Long advertising (program) | 0.02* |

Newspapers | 0.21 |

Election specials (TV) | 0.03* |

Network news (TV) | 0.10 |

Local news (TV) | 0.07* |

Radio | 0.10 |

Campaign discussions | 0.05 |

R multiple coefficient | 0.38 |

Source: Hofstetter et al. (1978, 568, table 3).

*Not significant for p ≤ .05.

The role of repeated messages was studied by Rothschild and Ray (1974) in an experiment using short ads about candidates. After the message had been presented once, 20 percent of the subjects remembered the candidates; after it had been presented six times, 55 percent of the subjects could name the candidates.

Proposition: | Message repetition (frequency) is an important factor in familiarizing voters with candidates and issues. |

We know that the attention given to political information, which is the first level of political participation, is linked to the resources individuals have at their disposal. Resources can be divided into two categories, each with the potential to augment or substitute for the other (Uhlaner 1984, 202). First, there are individual resources, such as education and income. Second, there are group resources, such as membership in an association or a union. The latter can offset the gap between individuals from different socio-economic segments of society. Generally, only socio-economic characteristics are taken into account in studies, which tends to lower the perception that people have of the relationship between socio-economic status and political knowledge.

The attention voters give to election campaigns in the newspapers is linked, in part, to education and socio-economic status. Radio is somewhere between newspapers and television (see Clarke et al. 1979, table 9.9). Moreover, there is a correlation (0.3 to 0.4 in 1974) between attention to one medium and to others. In other words, if voters pay attention to an election campaign largely through one medium, they will also tend to follow the campaign in the other media.

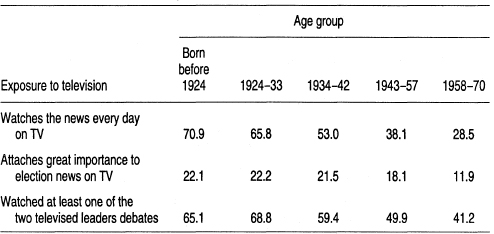

Clarke and his colleagues also noted in their 1979 election study that the attention voters give to television coverage of politics is linked to age. Older people are easier to reach through television. Data on the 1988 federal election are presented in table 1.10. Again, the youngest voters, who were between 18 and 30 years old during the 1988 election, were much less likely to listen to news on television every day than were people 65 years of age or more. Exposure to televised news seems to rise with age. The importance granted to televised election news also increases with age, but levels out when voters are over 45 years old. However, the idea that exposure to televised news increases with age may be misleading.

In fact, after the work done by Danowski and Ruchinskas (1983), there is reason to believe that the correlation between age and exposure to programs dealing with election campaigns on television is a generational phenomenon rather than a phenomenon of aging. The question is: Are today’s older people attentive to television programs dealing with elections because they have reached a stage in their lives where this is the thing to do (the aging hypothesis), or is it that people from this group (i.e., people born around the same time), as they mature and age together, share similar social experiences (Braungart and Braungart 1989, 20)? American data presented by Danowski and Ruchinskas (1983) show that, indeed, attention paid to television programs dealing with election campaigns has nothing to do with age. Rather, it is a group phenomenon: individuals born between 1900 and 1923 tune in to this type of program the most, more than individuals born either before or after this period.

Table 1.10

Exposure to television by age group during the 1988 federal election

(percentages)

Source: Based on 1988 Canadian Election Study.

The generation hypothesis is appealing, but it is not supported by all the data. For example, the 55-to-64 age group was the most attentive to the televised debates during the 1988 election campaign (table 1.10). Nor does the importance given to televised election news appear to be linked to the group born before 1924. The generation hypothesis would certainly bear closer study, given the important consequences that its confirmation could have on the use of mass television (broadcasting) as opposed to specialized television (narrowcasting) or other forms of communication.

Interest in Politics

The role of the mass media in stimulating interest in politics is important, since people who are interested are more likely to vote than those who are not (Milbrath 1965). Interest is generally defined as the amount of attention or psychological commitment in a specific campaign. This variable is loosely linked to exposure to the contents of a campaign (Lazarsfeld et al. 1948; Berelson et al. 1954). Lane (1965) suggests that greater access to political information leads to greater political awareness of society. Since interest in a campaign and exposure to media are correlated (Hofstetter et al. 1978; Clarke et al. 1979, 299, note 21), there is a link between exposure to advertising and interest (Atkin and Heald 1976). As shown in studies on televised debates and on the influence of media, ordinary television programs cannot easily generate an interest in politics; the interest must be there already. Moreover, if this interest exists and is strong enough to motivate an individual to pay attention to the media, it is quite likely that the media will heighten this interest. This explains the wide gap in the level of knowledge between people who show an interest in politics and those who do not (table 1.8).

MEDIA AGENDAS AND POLITICAL PERSONALITIES

Agenda Setting

The effect of political messages on the importance of issues in an election campaign has attracted the attention of a number of researchers. Lazarsfeld and colleagues (1948, 98) noted that the mass media had a significant impact during the 1940 American presidential election campaign by redefining the issues so that “issues about which people had previously thought very little, or had been little concerned, took on a new importance as they were accented by campaign propaganda.” Subsequent research on agenda setting focused on the relationship between the relative priority assigned to issues by the media and by the public (McCombs and Shaw 1972; McLeod et al. 1974). Although the correspondence between the media’s priorities and those of the general public can be explained otherwise, most observers agree that the media influence what people believe before they reach a decision, particularly an election decision. If candidates can lead voters to believe that their issues and qualities are of top priority, then they may gain the advantage. The goal, therefore, is to focus attention on what fosters the interests of the candidates, rather than to try to convince the voters about a particular issue.

In a series of experimental studies, Iyengar and Kinder (1987, 16) tested the assumption that the issues covered by television news become the most important issues. One experiment consisted of first measuring the opinions of the subjects on the most important issues facing the country. Then the people were divided into two groups. One group viewed newscasts to which a given topic, e.g., national defence, had been added. The second group watched unaltered newscasts. After one week, the opinions of the two groups were measured again. Other experiments consisted of collages of news items presented in a single session, followed by a measurement of opinions. In this second type of experiment, the number of news items on a given topic varied from group to group.

The results of the tests are revealing. The subjects gave more importance to the problems dealt with in the newscasts, except for inflation, which they already considered very important when the experiment began. Follow-up interviews one week after the end of the experiment showed that the effect was still the same.

Another way of tackling the effect of political messages on the importance of issues is to show the relationship between public opinion trends on a given topic over a period of several years and media coverage of the topic during the same period. Studies by Funkhouser (1973), MacKuen (1981, 1984) and Behr and Iyengar (1985) showed similar results. First, they showed that in the United States, there was a correlation between the amount of attention given to a topic by the media within a given period and the importance of this subject to the public. Second, they showed, using different data, periods and techniques, that public opinion changed when the media changed, and not before. Finally, the studies pointed to the persistent correlation between media coverage and public opinion, even when the economic and political indicators were held constant.

For example, Behr and Iyengar (1985) took into account indicators such as energy costs, U.S. dependency on foreign supplies, OPEC ministers’ meetings, speeches on energy by the U.S. president and, of course, media coverage, to explain the bi-monthly fluctuations in American public opinion regarding energy between 1974 and 1980. Also, by using a two-stage regression procedure, they were able to weed out these retroactive effects to obtain the net effect of media coverage on public opinion. They estimated that it took seven news items on energy to increase the importance of energy on the public’s agenda by 1 percent. This same 1 percent increase could be obtained, however, with a single news item, if this item led off a newscast. In a televised speech, the president of the United States could generate an average increase of more than 4 percent of the same indicator on the importance of the energy problem to the American public.

Although coverage is not the determining factor influencing public opinion, it does go a long way toward explaining changes in public opinion. Apparently, the people behind the main BBC evening newscast (“Nine O’Clock News”) believed this hypothesis when, during the 1987 British election campaign, they decided not to broadcast two reports they had commissioned, because the subjects of the reports (“inner cities” and “divided Britain”) had not been raised by the parties themselves. BBC officials were afraid of being accused of focusing on subjects that the parties had not debated (Blumler et al. 1989, 168).

In addition, programs such as televised debates might have decisive effects, not only on the political agenda, but also on the positions voters take on these issues. This was clearly shown in the English-language debate among the leaders of the three major political parties during the 1988 federal election in Canada. In the days immediately following the debate, support for the Free Trade Agreement between the United States and Canada fell by 6 percent (Johnston et al. 1989). Following the first Ford-Carter debate, which took place during the 1976 U.S. presidential campaign, voters were even more supportive of their favourite candidate’s position on the question of employment (Abramowitz 1978, 686).

Not only can the media contribute to setting the political agenda and influencing the positions people take on issues, but they can also change the criteria voters use to judge their elected representatives. This is what American authors call “priming.” If we look closely at the experimental studies done by Iyengar and Kinder (1987), we see that, in evaluating the performance of the U.S. president, the subjects in the experimental groups tended to place more importance on the theme inserted in the newscasts they watched than did the control groups. The effect is even clearer when the news item relates the theme to government responsibility (ibid., chap. 9).

The power of television in shaping the political agenda is even greater when individuals have fewer resources and political skills. Thus, individuals who take an interest in and are active in politics are influenced very little by ordinary newscasts (Iyengar and Kinder 1987, 90).

To examine the relationship between the political agenda and election advertising, Bowers (1972) compared the contents of newspaper election advertising with data obtained from opinion polls in all U.S. senatorial and gubernatorial election campaigns. He found a strong correlation between the perspective adopted in ads and that of voters. In a study on election advertising and the agenda of voters during the 1972 presidential election campaign, Shaw and Bowers (1973) concluded that the mention of an issue in an advertisement gives added importance to the issue, especially among those who have seen the ad. These associations can be largely explained by the fact that the candidates rely on opinion polls in the preparation of their advertising.

Proposition: | There is a correlation between the issues proposed by candidates in their advertising and the issues emphasized by the electorate. |

In a survey conducted in Michigan in 1974, Atkin and Heald (1976) showed a clear positive correlation between the importance given to an issue in election advertising and the importance given to that issue by voters. The correlation was even greater when a voter was less informed to begin with and was less exposed to other sources of information. In other words, the less informed voters are, the more likely they are to gain information from election advertising.

The role of political advertising is to sell the image of the candidates, rather than their political positions (Denton and Hahn 1986). In fact, few political ads present in-depth discussions of the issues or candidates’ positions on them (Joslyn 1980, 1986). On the contrary, even ads dealing with issues use ambiguous language to express a candidate’s interest in a certain issue without presenting the candidate’s specific proposals on it. The main purpose of such messages is to cultivate the candidate’s image, without alienating voters who disagree with that candidate’s specific positions. As Bennett (1977) noted, the ritual limitations of electoral discourse force candidates to deal with the issues: candidates are expected to campaign on the issues, and a candidate who does not deal with the issues is taking an enormous risk. Bennett adds, however, that talking about issues is not the same thing as taking a stand on them. Being too specific on the issues would break a cardinal rule of electoral discourse. Vague messages let voters feel closer to a candidate’s position than a precise message with which voters might disagree.

Page (1978, 178) summarizes the problem: “A candidate who takes a specific policy stand is bound to alienate those who disagree; but a candidate who promises peace, progress and prosperity, and projects an image of warmth and honesty, is likely to please almost everyone.”

These two rules of the game are readily reflected in political advertising. Candidates develop specific positions on the issues, but election advertising is not the vehicle they use to convey these positions. The presentation of specific positions is normally reserved for forums where these positions are likely to meet with approval and where the message is not likely to be seen or heard by a large number of people. Latimer’s work in Alabama (1985), which points out that competition on the issues is stronger at the state level than at the federal level, gives similar results. If the purpose of advertising is to reach a large number of undecided voters and nonpartisans (Shyles 1986), the message must be vague.

Using a vague message is based on the two rules already mentioned. First, the candidate must raise the issues during the election campaign. Second, the message must be sufficiently vague to avoid developing any opposition; voters must believe that the candidate agrees with their position.

There are indications that taking a stand on the issues could be more effective than being noncommittal or indecisive. Patton and Smith (1980), for example, compared candidates who did not take a stand with those who did, concluding that those who abstained were not rated nearly as well. Similarly, Rosen and Einhorn (1972) reported that candidates who were neutral on the issues were considered less honest, less direct and less well informed than their opponents who took a stand. In an experiment, Rudd (1989) showed that when candidates use vague messages and their opponents take a clear stand on the issues, the more precise candidate is rated higher. Mansfield and Hale (1986) concluded that the perceptions of television viewers are formed by a combination of issues and images of candidates. This conclusion is true both for viewers who watch television to obtain information and for those who watch television to relax. As in the case of newscasts, candidates consider that newspaper advertising enables them to deal with more complex subjects than do the broadcast media. One candidate wrote, “A newspaper ad can be read more than once” (Latimer 1989, 341).

Proposition: | Candidates who take a position on the issues in their advertising rate higher with the electorate than candidates who do not. |

Political Personalities

In the United States, much attention is given to political personalities. To the extent that the role of candidates is seen as important, party labels are not. Election campaigns are designed, therefore, to highlight the qualities of the candidates. For observers of the U.S. political scene, the primary mission of election propaganda is to focus on the image of the candidate and not on the obligations of the legislator (Latimer 1985). The roles of images and issues in advertising have been studied from many angles. In general, these studies show that image dominates (see Mintz 1986; Latimer 1985; Joslyn 1980; Humke et al. 1975; Bowers 1972). When voters are questioned about candidates, it is easier to get answers on the overall evaluation of these candidates’ personal images (good or bad, honest or dishonest, hard worker or lazy) than answers on the candidates’ positions on issues or their ideology (Clarke and Evans 1983, 89). This observation meshes with Zajonc’s thesis (1980), which states that emotional factors come before those of knowledge (figure 1.1). Rhetoric on the duties of the legislator only emphasizes the candidate’s qualities.

Televised debates between party leaders or between candidates are the ideal means of comparing the qualities of these personalities. During the debates between candidates for Nebraska state senator in 1988, Wanzenfried and colleagues (1989) measured changes in young voters’ perceptions of five candidate characteristics: competence, personality, sociability, composure and extroversion. Their results showed that for the experimental group there was no difference between their evaluation of the competence or sociability of any of the candidates before and after the debate. The evaluation of the other three characteristics varied according to the candidate. Following the first televised debate in the United States, the Kennedy-Nixon debate in 1960, Katz and Feldman (1962) noted a change in viewers’ perceptions of the competence and personality of the two candidates.

During the 1988 federal election campaign, it was noted (Johnston et al. 1992) that among people who saw the leaders debates, assessment of the competence and personality of the Liberal party leader, John Turner, improved considerably in the five days following the debates, while assessment of the competence of the NDP leader, Ed Broadbent, deteriorated.

I conclude, therefore, that television viewers can distinguish the various qualities of political personalities and, moreover, that which interests us most here, that television can change people’s evaluation of these personalities.

McIntosh (1989) used the second debate between George Bush and Michael Dukakis, the 1988 U.S. presidential candidates, to measure changes in attitudes toward the candidates among a group of junior college students. The subjects’ preference was measured using the following question: “Who would you tend to vote for right now?” The answers were coded on a scale of 1 (“Bush, very certainly”) to 13 (“Dukakis, very certainly”). The percentage of those who strongly favoured Bush remained the same before and after the debate. The percentage of those who strongly favoured Dukakis increased significantly (from 21 percent to 41 percent). What is relevant here is that this increase simply shows a consolidation of the intention to vote for Dukakis by those who had already expressed the intention of voting for him. In other words, what we witnessed was a reinforcement of the pro-Dukakis vote, with no similar movement on the part of those leaning toward Bush. This reinforcement effect is dominant in these debates, both in the United States (Hagner and Rieselbach 1978) and in Canada (LeDuc and Price 1985; Johnston et al. 1992).

Moreover, it was shown that the U.S. public obtains most of its information on the candidates in the House of Representatives through advertising. In their newscasts and public affairs programs, the media present little information on the constituency candidates, unless one of them provokes a controversy or attracts attention through a dramatic event (Latimer 1989). In Canada, the situation appears similar.

For example, it has been reported that, in 1974, barely 15 percent of election news published in the dailies dealt with people other than the leaders (Clarke et al. 1979, 279), a trend repeated in the 1979 election (Fletcher 1981c, 281). During the 1988 Canadian federal election campaign, the CBC devoted 7.5 percent of its national newscasts to local candidates. There is every reason to believe, however, that the amount of air time devoted to local candidates during local newscasts should be much greater. The Radio-Canada news program “Téléjournal,” which in the Canadian context is both a national newscast (Canada) and a regional newscast (Quebec), had, by the same time, devoted twice as much air time to candidates as did the CBC news broadcast.

Tests on the relative effectiveness of election advertising showed that ads dealing with issues were more persuasive than those focusing on the image of the candidates. More specifically, advertisements on issues produced better evaluations of candidates (Kaid and Sanders 1978) and a greater indication of an intention to vote for them (Garramone 1985) than ads pushing the image of a candidate. In an experimental study, Roddy and Garramone (1988) showed that, in the case of attacks and counterattacks through advertising, the most devastating are those that attack the issues.

The authors of U.S. studies (Patterson 1980; DeFleur and Ball-Rokeach 1975; Strouse 1975; Jacobson 1975; Cundy 1986) also agree that when the candidate is not well known, the impact of televised information is even greater. When a candidate has acquired a public image, new information about the candidate is not likely to change people’s perception. Election advertising, therefore, is all the more effective when the candidate is not well known, as is the case more at the beginning of a campaign than at the end.

Proposition: | The less known the candidate, the more effective election advertising is. |

Proposition: | For local candidates (as opposed to party leaders or stars), election advertising is one of the few means of gaining exposure. |

Proposition: | Advertising related to issues seems to produce better results than advertising related to personalities. |

MEDIA EFFECTS ON VOTING

The strongest argument against the idea that massive use of radio and television dictates election success comes from studies showing that very few voters change their voting intentions during an election campaign. The literature on the subject has been compiled by Klapper (1960, chaps. 2 and 4) and Weiss (1969), and the conclusions drawn from this literature are well known. Mass media influence the attitudes of audiences only in the absence of mediating factors, such as the previous attitudes of the audience and the social influences on these individuals. When mediating factors are present, the effect of mass communication will most often be to activate existing attitudes and reinforce predispositions (Jacobson 1975). In their study on the attitudes of Canadian voters, the authors of Political Choice in Canada conclude, “Evidence of direct effects of media attention and party contact on changing people’s voting preference may be lacking, but the data suggest the presence of reinforcement effects” (Clarke et al. 1979, 296).

More recent studies, however, indicate that the effects of the mass media go beyond the simple reinforcement of attitudes. Evidence that election advertising has a significant impact is nevertheless slim. For lack of a better approach, studies have used grouped data indicators, correlations, or in some cases examinations of atypical populations, such as the study conducted on college students (Cundy 1986, 212). The results of these studies tend to be positive. In his study on candidate and party expenses during the 1966 and 1970 Quebec elections, Palda (1973) found a significant link between advertising spending and election results. Using a similar procedure during the elections for the U.S. House of Representatives, Wanat (1974) also found a significant link between the amount spent on television advertising by a particular candidate and the number of votes won.

Using a different approach, Joslyn (1981) pursued the same objective. He compared election advertising expenses with survey data in electoral districts during the 1970, 1972 and 1974 elections. Using multivariate analysis, Joslyn showed that election advertising spending is the third best indicator of voter defection and voter loyalty (the first two being party identification and incumbency). Mulder (1979) used the same basic approach to study the mayoral elections in Chicago in 1975. He reported weak but statistically significant correlations between exposure to political ads and voting preferences. As Jamieson (1989) tried to show, it is the sociopolitical context that gives meaning to a message. We should expect ads that attack a candidate to polarize the debate because of their boomerang effect on voters who favour the candidate attacked. Also, focus group tests tend to show that Canadian voters who are not interested in politics are also less likely to be angered by negative advertising (Wearing 1988, 115). This makes the parties’ task even more difficult. Although election advertising and debates between leaders can polarize voters, it is highly unlikely that public affairs programs and newscasts can do the same.

Public affairs programs and newscasts, like advertising and such special events as leaders debates, nonetheless give voters useful information in making their election choices. Among all the types of news categories presented by the media, one demands special attention: the publication of opinion poll results during election campaigns. It is claimed that the information voters derive from polls encourages them to join the ranks of the most popular party – the “bandwagon” effect – or to vote strategically. Voting strategically means voting for a second-choice candidate; for example, take the case of a voter who fiercely opposed the proposed Free Trade Agreement between Canada and the United States and whose normal voting preference would have been the NDP. During the 1988 election campaign, the voter realizes that the party with the best chance of beating the government party and its free trade policy is the Liberal party. If the voter decides to abandon the first choice – the NDP – in order to vote Liberal, the voter is said to be voting strategically. Opinion polls on party popularity give voters information enabling them to make this type of decision.

As seen in the study of the 1988 federal election campaign (Blais et al. 1990), people who kept up to date on poll results had the most accurate perspective on who was going to win or lose the election. These people were therefore potentially better armed to make a strategic decision. And that is what some of them did.

The study by Blais and his colleagues (1990) also draws our attention to a phenomenon that is both comical and revealing. Two weeks before the end of the 1988 election campaign, Gallup published the results of a poll mistakenly showing the Liberals to be ahead of the Conservatives. Publication of these results had a greater effect on people who, during the week preceding the interviews, had no idea of the results of opinion polls on party popularity. Thus, during the final two weeks of the campaign, people who did not know the previous poll results were more likely to believe that the Liberals would win. To the extent that the relationship between publication of the faulty Gallup poll and voters’ expectations is not misleading, we may draw conclusions on the virtues of prohibiting the publication of polls for a few days before the election.

Advocacy Advertising

Studies on the mass media remind us that the credibility of the source is an important factor in estimating the impact of the message. Advertising by interest groups lets a party or candidate benefit from support while escaping election spending regulations. It also lets these groups do the “sales pitch” for them. A recent but already classic case of this type linked the Democrats’ presidential candidate Michael Dukakis to criminal Willie Horton. Television ads by an organization that was technically independent of the Bush campaign let Americans know about a black prisoner who raped a white woman while on a weekend pass. Weekend passes were part of the prisoner rehabilitation program in the state of Massachusetts, where Dukakis was governor. By the end of the election campaign, one voter in four knew about this issue. At the beginning of the campaign, 36 percent of voters felt that Dukakis was a little soft on criminals. By the end of the campaign, that figure had climbed to 49 percent (Diamond and Marin 1989, 386). The U.S. literature is full of such examples showing that advertising by political action committees and interest groups is effective.

In Canada, an Environics survey conducted in December 1988, the month after the federal election, showed that third-party election advertising is, according to voters themselves, an important factor in voting. Nearly three people in ten (27 percent) consider third-party advertising and leaders debates very important in their voting decisions. Moreover, only 13 percent considered parties themselves as very important, while even fewer considered information distributed to residences (11 percent) and opinion polls (11 percent) as important (Adams 1990).

In a survey conducted four months after the November 1988 election, 31 percent of Canadians admitted that their vote had been influenced by third-party ads, and half of these (14 percent) said the ads had had a significant effect. During the survey conducted by the same company in December 1988, 27 percent said that third-party advertising was important in their electoral choice (Adams 1990). These are, however, raw survey data that called on interviewees’ memory of how their voting preferences evolved over the campaign. Moreover, the processing of the data was very elementary. The fact remains that there is a striking parallel between the daily quantity of advertising by the coalition for free trade and the return to power of the party bearing the free trade standard (see Johnston et al. 1992).

From this limited information, we cannot determine whether advertising paid for by third parties is more effective or less effective than that paid for by official agents of the parties or candidates. To the extent that advertising paid for by para-partisan organizations is added to that of the parties and candidates, however, a larger audience is reached or the same audience is reached more often.

CONCLUSION AND DISCUSSION

In this literature review, we have seen that the main focus of television newscasts during election campaigns is the leaders of the main parties and the issues they define. The information retained by the voter certainly depends on the degree of exposure to these information sources. This degree of exposure depends on people’s interest in the election campaign, which depends in turn on how exciting the election is perceived to be.

We have also seen that the news coverage of political parties on the public broadcasting network reflects the compromise that political parties themselves reached in the name of the principle of balance. The formula resulting from this compromise serves as an index to measure the distribution of the time allotted to each party in newscasts. Two biases result from applying the compromise: on the one hand, the distribution of time among the parties is based not on the importance of the day’s news, but on what happened three, four or five years ago. To the extent that the strength of parties is relatively stable, the consequences are more than negligible. In the case where the relative strength of parties would change radically – as appears to be the case in Canada since the beginning of the 1990s – the bias would be all the more obvious. The second bias is the privilege enjoyed by the New Democratic Party as a result of the compromise formula.

I think it wise that a Crown corporation such as the CBC should seek to distribute air time in such a way that it does not become a greater target for criticism by political parties represented in the House of Commons. Moreover, given that the main parties have agreed on a basic formula and that this formula is not incompatible with the principle of journalistic objectivity, it seems advisable not to intervene in these processes unless it is to confirm the independence of the Corporation relative to the parties and political power.

The general impression of Canadian political parties gained by watching televised news is somewhat negative. Some might blame journalists, producers and broadcasters for presenting politicians and their activities in a bad light. It also may be that the source of this negative impression lies in the discrepancy between the high standards citizens set for their politicians and reality. As long as political parties live on the contributions of private sector corporations, and citizens do not accept this form of party financing as normal, it is likely that politicians and parties will continue to be viewed negatively. If any action should be undertaken to enhance the image of politicians and parties, in my view it must come more from the parties and politicians themselves than from the media, the mirrors that reflect them to society.

Election campaigns are the high points in a democracy. They are periods when candidates, parties and policies are examined closely. It is unacceptable that by the end of an election campaign more than one voter in four still cannot identify a single candidate in his or her riding. What can be done? We have seen that people who watch television news and read newspapers are those most likely to be able to identify candidates. To increase the level of knowledge, it should suffice to increase the quantity (and repetition) of information in the media. The problem lies with those who do not avail themselves of these sources of information. How can they be reached? I have pointed out that it is possible to use advertising to increase the level of knowledge of those who are not interested in politics and who do not follow political news. Holding media events such as leaders debates is also a way of reaching a less attentive group of citizens, particularly youth. These debates provide an opportunity to acquire information on political personalities and their positions on the issues of the day.

In my research review, I drew attention to a specific type of news: polling results. Given people’s interest in this subject, it is appropriate to spend some time on the topic. What seduces or dismays in opinion polls during election campaigns is the information on the distribution of voter intentions by party. People who know this information are more likely to predict correctly the respective strength of the parties at the finish line than people who were not informed of the poll results. This is the first effect of the publication of polls. This information is added to other information already held by the voter so that as informed a decision as possible can be reached.

Some people fear, however, that the publication of an erroneous or abnormal poll may deceive voters. This is the origin of the idea of prohibiting the publication of opinion poll results, either entirely or during the last portion of the election campaign. Studies of the 1988 election campaign (Blais et al. 1990; Johnston et al. 1992) lead to two observations. In 1988, the notorious Gallup poll was published two weeks before election day. To avoid problems caused by this poll, it would have been necessary to prohibit publication of polls at least 14 days before the election. Second, this defective Gallup survey had its effect mainly among those who had no direct knowledge of the poll. If a publishing ban had been in effect, people would probably have learned about the poll through rumours, a channel that would become widespread if the media could no longer publish poll results. The study on the 1988 election campaign in Canada confirms that it is the widespread distribution of public information that guarantees better voter judgement.

Within the scope of research on mass media and election campaigns, I focused on election advertising. The advantage offered by television advertising is that it reaches a segment of the electorate that is not very interested in public affairs – and consequently invests little in acquiring political information – but does watch television. This potential election audience can easily avoid exposure to election propaganda by not reading newspapers, magazines and brochures, not attending political meetings, not watching public affairs programs and not discussing politics. But because this group watches television a great deal, it cannot escape election advertising. It is therefore the least informed citizens who are likely to learn the most through televised election advertising.

Televised election advertising is to recent election campaigns what neighbourhood meetings were to the campaigns of long ago. Media strategists have replaced election organizers as propagandists of the “good news.” They visit homes via television, but for how much longer will this method still be effective? Will the fragmentation of audiences by the advent of many specialized television channels complicate significantly the task of reaching the entire public? Will new generations be as tuned in to television as have been the present generations, for whom television was a great innovation?

In future elections, it will undoubtedly be necessary to advertise through many channels in addition to the traditional television networks to reach all potential voters.

APPENDIX

PROPOSITIONS ABOUT ELECTION ADVERTISING ON TELEVISION

Proposition: | Election advertising increases voters’ knowledge of issues and candidates. |

Proposition: | Exposure to campaign advertising and interest in politics are correlated. |

Proposition: | Election advertising is a major source of information for voters. |

Proposition: | The less politically aware the voter, the more important election advertising becomes. |

Proposition: | Message repetition (frequency) is an important factor in familiarizing voters with candidates and issues. |

Proposition: | There is a correlation between the issues proposed by candidates in their advertising and the issues emphasized by the electorate. |

Proposition: | Candidates who take a position on the issues in their advertising rate higher with the electorate than candidates who do not. |

Proposition: | The less known the candidate, the more effective election advertising is. |

Proposition: | For local candidates (as opposed to party leaders or stars), election advertising is one of the few means of gaining exposure. |

Proposition: | Advertising related to issues seems to produce better results than advertising related to personalities. |

NOTES

This paper was completed in April 1991.

The author wishes to thank two anonymous evaluators and Frederick J. Fletcher, the research coordinator for media and elections, for their comments on an initial version of this text.

1. Other factors, such as the significant development of the public relations and public opinion poll industries, have allowed the leaders of national parties to relegate their ridings and their candidates to a secondary role, both in the parties and, of course, in politics in general (Butler and Kavanagh 1974, 201).

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Abramowitz, A.I. 1978. “The Impact of a Presidential Debate on Voter Rationality.” American Journal of Political Science 22:680–90.

Adams, Michael (Environics Research Group). 1990. “Public Opinion and Third Party Advertising.” Brief to the Royal Commission on Electoral Reform and Party Financing. Ottawa.

Atkin, C., L. Bowen, O. Nayman and K. Sheimkopf. 1973. “Quality versus Quantity in Televised Political Ads.” Public Opinion Quarterly 37:209–24.

Atkin, Charles, and Gary Heald. 1976. “Effects of Political Advertising.” Public Opinion Quarterly 40:216–28.

Axford, Barrie, and Peter Madgwick. 1989. “Indecent Exposure? Three-Party Politics in Television News during the 1987 General Election.” In Political Communications: The General Election Campaign of 1987, ed. I. Crewe and M. Harrop. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Baker K.L., and H. Norpoth. 1981. “Candidates on Television: The 1972 Electoral Debates in West Germany.” Public Opinion Quarterly 45:329–45.

Behr, R.L. 1985. “The Effects of Media on Voters’ Considerations in Presidential and Congressional Elections.” Ph.D. diss., Yale University.

Behr, R.L., and S. Iyengar. 1985. “Television News, Real-World Cues, and Changes in the Public Agenda.” Public Opinion Quarterly 49:38–57.

Bennett, W. Lance. 1977. “The Ritualistic and Pragmatic Bases of Political Campaign Discourse.” Quarterly Journal of Speech 63:219–38.

Berelson, B.R., P.F. Lazarsfeld and W.H. McPhee. 1954. Voting. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Bernier, Robert. 1991. Gérer la victoire? Organisation, communication, stratégie. Boucherville: Gaëtan Morin.

Bishop, George, Robert Meadow and Marilyn Jackson-Beeck, eds. 1978. The Presidential Debates: Media, Electoral, and Policy Perspectives. New York: Praeger.

Blais, A., R. Johnston, H. Brady and J. Crête. 1990. “The Dynamics of Horse Race Expectations in the 1988 Canadian Election.” Paper presented to the Canadian Political Science Association annual meeting, Victoria.

Blumler, J.G., and D. McQuail. 1968. Television in Politics. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Blumler, J.G., M. Gurevitch and T.J. Nossiter. 1989. “The Earnest versus the Determined: Election Newsmaking at the BBC, 1987.” In Political Communications: The General Election Campaign of 1987, ed. I. Crewe and M. Harrop. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Bowers, Thomas A. 1972. “Issues and Personality Information in Newspaper Political Advertising.” Journalism Quarterly 49:446–52.

Braungart, R., and M. Braungart. 1989. “Les générations politiques.” In Générations et politique, ed. J. Crête and P. Favre. Paris: Économica.

Butler, D., and D. Kavanagh. 1974. The British General Election of February 1974. London: Macmillan.

Campbell, Angus, Phillip E. Converse, Warren E. Miller and Donald E. Stokes. 1964. The American Voter. New York: John Wiley.

Campbell, James E., John R. Alford and Keith Henry. 1984. “Television Markets and Congressional Elections.” Legislative Studies Quarterly 9:665–78.

Canada. Elections Canada. Various. Report of the Chief Electoral Officer of Canada. Ottawa: Minister of Supply and Services Canada.

Canadian National Election Study. 1988. Institute for Social Research, York University. Principal investigators: Richard Johnston, André Blais, Henry E. Brady and Jean Crête. Funded by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council.

Caron, André H., Chantai Mayrand and David E. Payne. 1983. “L’imagerie politique à la télévision: les derniers jours de la campagne référendaire.” Canadian Journal of Political Science 16:473–88.

Chaffee, S.H. 1977. “Mass Media Effects: New Research Perspectives.” In Communication Research – A Half-Century Appraisal, ed. D. Lerner and L.M. Nelson. Honolulu: University Press of Hawaii.

Chaffee, S.H., and Y. Miyo. 1983. “Selective Exposure and the Reinforcement Hypothesis: An Intergenerational Panel Study of the 1980 Presidential Campaign.” Communication Research 10:3–36.

Clarke, H.D., J. Jenson, L. LeDuc and J.H. Pammett. 1979. Political Choice in Canada. Toronto: McGraw-Hill Ryerson.

Clarke, Peter, and Susan H. Evans. 1983. Covering Campaigns: Journalism in Congressional Elections. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Comstock, George. 1982. “Television and American Social Institutions.” In Television and Behavior, vol. II. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Corner, J. 1979. “‘Mass’ in Communication Research.” Journal of Communication 29:26–32.

Cotteret, J.M., C. Émeri, J. Gerstlé and R. Moreau. 1976. Giscard d’Estaing-Mitterrand: 54774 mots pour convaincre. Paris: Presses universitaires de France.

Crête, J. 1984. “La presse quotidienne et la campagne électorale de 1981.” Recherches sociographiques 25:103–14.

Crewe, Ivor, and Martin Harrop, eds. 1989. Political Communications: The General Election Campaign of 1987. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Cundy, Donald T. 1986. “Political Commercials and Candidate Image.” In New Perspectives on Political Advertising, ed. L.L. Kaid, Dan Nimmo and Keith R. Sanders. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press.

Danowski, J.A., and J.E. Ruchinskas. 1983. “Period, Cohort, and Aging: A Study of Television Exposure in Presidential Election Campaigns, 1952–1980.” Communication Research 10:77–96.

Dawson, P., and J. Zinser. 1971. “Broadcast Expenditures and Electoral Outcomes in the 1970 Congressional Elections.” Public Opinion Quarterly 35:398–402.

DeFleur, M.L., and S.J. Ball-Rokeach. 1975. Theories of Mass Communication. 4th ed. New York: Longman.

Denton, Robert E., and Dan F. Hahn. 1986. Presidential Communication: Description and Analysis. New York: Praeger.

Desmond, R.J., and T.R. Donohue. 1981. “The Role of the 1976 Televised Presidential Debates in the Political Socialization of Adolescents.” Communication Quarterly 29:302–308.

Devlin, Patrick L. 1986. “An Analysis of Presidential Television Commercials, 1952–1985.” In New Perspectives on Political Advertising, ed. L.L. Kaid, Dan Nimmo and Keith R. Sanders. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press.

———. 1989. “Contrasts in Presidential Campaign Commercials of 1988.” American Behavioral Scientist 32:389–414.

Diamond, Edwin, and Stephen Bates. 1984. The Spot: The Rise of Political Advertising on Television. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Diamond, Edwin, and Adrian Marin. 1989. “Spots.” American Behavioral Scientist 32:382–88.

Fletcher, Frederick J. 1981a. The Newspaper and Public Affairs. Vol. 7 of the research studies of the Royal Commission on Newspapers. Ottawa: Minister of Supply and Services Canada.