THE ORGANIZATION OF TELEVISED LEADERS DEBATES IN THE UNITED STATES, EUROPE, AUSTRALIA AND CANADA

Robert Bernier Denis Monière

INTRODUCTION

THE TELEVISION ERA has profoundly altered the political process by expanding audiences, personalizing power, reducing the role of political parties and “nationalizing” the political debate. As in most Western societies, “Television remains the primary source of news information for Canadians. In fact, the public is most likely to rank this medium first for objectivity, accuracy and in-depth reporting” (Frizzell et al. 1989, 77, citing Adams and Levitin 1988).

Fred Fletcher calculated that in the early 1980s 52 percent of voters derived their news information from television, compared with 30 percent from newspapers and 11 percent from radio (Fletcher et al. 1981, 285). In France, an IFREP (Institut français de recherche psychosociologique) poll taken on the eve of the 1988 presidential election revealed that 77 percent of French people based their impressions of the candidates on what they had seen on television (Le Parisien libéré, 25 March 1988). Similar results were observed in Germany where 52 percent of respondents named television as their prime source of information on political events, compared with 34 percent for daily newspapers and 10 percent for radio (Metzner 1984, 39).

Before television, citizens rarely had an opportunity to witness the political parties, and their ideas, in direct confrontation with one another. They seldom heard political speeches. Now, politicians enter our homes nightly through television news telecasts. There used to be a tradition of public debates between political candidates, but those debates usually featured local candidates, not party leaders. There were, obviously, exceptions, such as the celebrated debates between Abraham Lincoln and Stephen Douglas in the summer of 1858. In the province of Quebec, Charles-Eugène Boucher of Boucherville debated with Liberal leader Gustave-Henry Joly before an audience of 6 000 in August 1875.

Television has expanded public debate to a national forum. The leaders of the principal political parties use television to communicate instantly with the electorate. No politician today can afford to ignore this medium, because from the time television became a factor in political communication strategies, the images and personalities of the candidates, as projected on television, have been one of the leading factors in determining people’s voting choices.

The Role and Importance of Debates in the Electoral Process

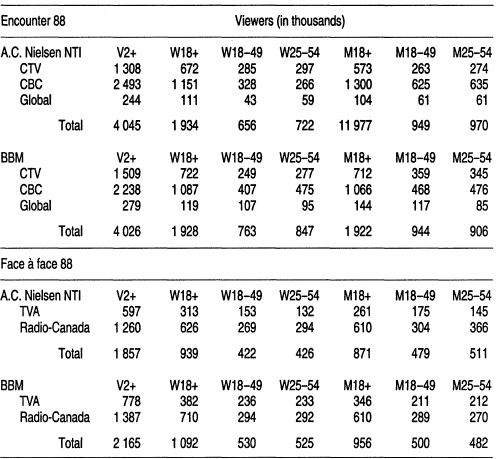

Because of their exceptional and spectacular nature, televised debates draw huge audiences, far larger, in fact, than any other type of political event. Katz and Feldman (1962) estimated that 60 to 65 percent of adult Americans watched the first Kennedy-Nixon debate in 1960. It has also been estimated that about 6 percent of American voters, or some four million people, made up their minds on the basis of this debate (Hellweg and Philips 1981). According to Sears and Chaffee (1979), the audience share for the first Ford-Carter debate in 1976 reached 70 percent. In 1980, 120 million people are estimated to have seen at least one of the Carter-Reagan debates. In France, the 1988 debate between François Mitterrand and Jacques Chirac attracted some 26 million viewers. In Canada, the 1988 French-language debate was seen by more than two million viewers and the English-language debate by four million. Close to 30 percent of voters said that they made up their minds on the basis of the debates (Gallup Report 1988).

This interest can be explained by the unpredictable and competitive nature of televised debates. Viewers’ curiosity, it seems, is piqued by the debates’ confrontational character. Interest is also stimulated by the fact that it is the viewers who will ultimately decide who wins and who loses.

Televised debates are helpful for voters because they provide the only opportunity for them to compare the positions, personalities and abilities of the candidates at the same time and in the same place. Voters can therefore compare the performances and policies of the candidates, and more easily evaluate the similarities and differences in the positions of the various parties. Author Antonine Maillet, who moderated the 1988 French-language debate, explained the role of the debate in the following terms: “Tonight, Canadians have a unique opportunity to experience democracy in action, for it is democracy, combined with modern technology, that enables citizens throughout the country to meet, in a single location, the leaders of the three largest parties, who have come here to personally present their visions of Canada.”

The unique characteristic of televised debates is that they offer citizens an inexpensive, first-hand source of comparative information. Election campaigns have traditionally provided information sporadically and indirectly. Voters acquired their political knowledge by reading newspapers, listening to news broadcasts and watching campaign commercials. All this was second-hand information, moulded and mediated by journalists or political communication specialists. Apart from attending political meetings and reading party platforms, which few voters do, watching televised debates provides the only direct, easy and inexpensive access to political views. In addition, according to Miller and Mackuen (1979, 344), the debates serve to increase the public’s knowledge of politics and politicians.

In Canada, televised debates gained prominence during the 1980s as pivotal events in election campaigns. Canada kept pace with other Western democracies in this regard, holding four federal political debates by 1989, while the United States held presidential debates in five elections and France in three. Political strategists and party leaders became convinced of the need for this media exercise as a tool to maximize their election support. There are increasing numbers of swing voters and there has been a significant decline in party loyalty. As a result, voters increasingly wait until the actual campaign before deciding which way to vote. For example, in 1984, 50 percent of Canadians had not made up their minds when the election was called (Fletcher 1988, 161). All these factors favour televised debates, especially when the party leaders are relatively unknown, as was the case in 1984.

Party leaders are willing to participate in televised debates when they believe it is to their advantage, that is, when they expect to increase their support. However, the leader of a party in power with a comfortable lead in voter support will want to find reasons for avoiding a debate. Leaders are more eager to participate if they are behind in the polls, if they are ahead but losing ground, or if the polls indicate that their level of support is fluctuating.

Although it is difficult to determine the exact effect that debates have on the final results of an election, significant shifts in voters’ intentions can be seen as a result of the debates. The impact of a debate is especially significant during a tight race, and a shift of two to three percentage points in the undecided vote could mean the difference between victory and defeat. In France, for example, Valéry Giscard d’Estaing’s 1974 victory over François Mitterrand has been attributed to their performances in the televised debate. Okrent described the situation as follows:

According to a poll taken the same night, the debate changed the opinions of 10 percent of the viewers. Forty-seven percent felt that Valéry Giscard d’Estaing won the debate, and 38 percent preferred Mitterrand. The shift in votes in both directions as a result of the debates was less than 3 percent. This figure was obtained by comparing the election results with polls taken before the second round. The television debate was only marginally influential, but it was the undecided voters who determined the outcome of the election. (1988, 138)

In the end, Giscard d’Estaing’s margin of victory was 424 599 votes, or 1.9 percent of the total.

In Canada, televised debates also played a key role in the 1984 and 1988 election campaigns. The 1984 debate between Brian Mulroney, John Turner and Ed Broadbent was won by the Progressive Conservative leader, according to the 78 percent of Canadians who felt that he had outperformed Turner. Subsequent opinion polls revealed large shifts in voters’ intentions: “The 1984 shift was the largest since the beginning of national polling in Canada, a period spanning 13 previous federal elections. The polls showed the Liberals with 49 percent of the decided vote in early July 1984, a 10 percent lead over the Conservatives. Within three weeks of the election call on July 9, Liberal support had dropped to 39 percent, ending up at 28 percent on election day” (Fletcher 1988, 161).

Analysts agree that this shift was the result of the leaders’ performances during the televised debates. Poll results in Quebec after the French debate indicated a 10 to 12 percent shift in voter intentions away from the Liberals and toward the Progressive Conservatives (Fletcher 1988, 181). It was noted, as well, that commentaries by journalists after the debate influenced voters’ choices. The same phenomenon occurred in 1988 when the debate enabled John Turner, whose party was in third position in the polls before the debate, to make a spectacular comeback and preserve the Liberals’ status as the official opposition.

Although controversy still surrounds the effect that televised debates have, and the findings of the main studies are inconclusive, political communication specialists have identified eight effects of televised political debates (Trent and Friedenburg 1983, 263–73):

1. By their dramatic nature, debates help stimulate interest in politics and attract very large audiences.

2. They reinforce the partisan views of those who have already decided to support a particular party, that is, they have a confirming effect.

3. Debates may make it easier to recruit campaign workers.

4. Debates result in few conversions or significant shifts in voters’ intentions; however, they may be a deciding factor in a tight race, making the difference between election victory and defeat, as was the case in the election of U.S. President Kennedy in 1960.

5. Debates help voters determine what is important and what the basic issues are.

6. Debates raise the level of awareness and understanding of problems and party policies.

7. They enable candidates to make themselves more widely known or to correct negative aspects of their public image.

8. Debates help legitimize political institutions and encourage the political involvement of young people.

Despite these significant contributions to the democratic process, televised debates are not unanimously applauded. They have been criticized for emphasizing image and favouring appearance at the expense of substance, and for failing to provide voters with added information. They are said to help the most superficial candidates and prevent thinking candidates from winning elections. They tend to relate political success to candidates’ abilities as performers rather than to their wisdom or the correctness of their judgement. In the early 1960s, when André Laurendeau pondered the value of this innovation in the democratic process, he decided that “qualities that make a good performer on television are not necessarily qualities that make a good politician” (1962). However, in the era of “new politics,” surely communication skills are an essential aspect of political skills. There are also those who deplore the fact that the media spend too much time covering the negotiations surrounding the debate format, to the detriment of more pressing issues (Swerdlow 1984, 11).

This study compares televised debate practices in several democracies to clarify the relationship between the debate’s format, its internal dynamics, its content and its impact. By analysing the way debates are organized in the United States, Europe (France, the Netherlands, Germany and Scandinavia), Australia and Canada, we hope to answer the following questions: Who should organize debates? Who should be allowed to participate? How many debates should there be? How long should they last? When should they take place? What role should journalists play?

The debate format greatly affects the dynamics of the interaction between leaders, as well as the content, and we will see that the formats vary considerably from one country to another. Historically, there have been three basic models: the parallel news conference format used in Sweden and the United States; the direct confrontation format used primarily in Europe; and finally, the mixed format, which includes both direct interaction between the candidates and an active role for journalists.

TELEVISED DEBATES IN THE UNITED STATES

In the United States, the process of negotiating the organization and formats of televised presidential election debates has gone through several variations since 1960.

The four debates held in 1960 were preceded by a series of 12 negotiating sessions between the television networks and the candidates’ representatives. The networks preferred a direct confrontation between the candidates, while the candidates’ advisers insisted that a number of journalists participate in the debate together with a moderator. The candidates’ advisers won the struggle, setting the stage for their continued domination of the format negotiating process (Kraus 1988, 38).

Between late 1960 and 1976, no debates were held during the three presidential elections, apparently because the candidates declined to participate. This was largely because of the political climate created by the Vietnam War and, later, the Watergate affair.

When President Gerald Ford expressed an interest in meeting Jimmy Carter in a televised debate in the fall of 1976, a new group entered the negotiation process. The League of Women Voters Education Fund, a nonprofit organization with no ties to the government or political parties, became the debate organizer. Their involvement permitted broadcasters to cover the debates as news events. It should be remembered that a special Act of Congress was required in 1960, setting aside the equal time provisions in section 315 of the Communications Act of 1934, to permit broadcasting of the Kennedy-Nixon debates. Without that resolution, broadcasters would have had to provide equal time to the many minor party presidential candidates, which would have effectively prevented broadcasting of the debates (Kraus 1988, 40).

In 1976, however, Congress refused to set aside the Act to permit the televising of debates between the major presidential candidates. Instead, a complex series of legal manoeuvres was undertaken to allow the networks to cover the debates as “bona fide media events” sponsored by a nonpartisan group (in this case, the League of Women Voters). News coverage is exempt from the equal time provisions. The resulting body of legal opinion influenced the course of the negotiations surrounding the 1976 debates. There was much criticism and bitter discussion over the participation of candidates from smaller parties, the selection of journalists, and the roles of the television networks and the organizer. Candidates from smaller parties sued the League of Women Voters and the television networks in an attempt to be allowed to participate in the debates but the two-way debates prevailed (Kraus 1988, 40–41).

In the fall of 1976, Republican President Gerald Ford faced Democratic challenger Jimmy Carter in three campaign debates, while Republican vice-presidential candidate Robert Dole faced Democrat Walter Mondale in another. The formats were similar to those established in 1960 in that, in some of the debates, the candidates were allowed to make opening and closing remarks, and the debates included a moderator and a panel of journalists who posed questions to the candidates. The candidates were also given time to refute their opponents’ remarks.

In contrast to the 1960 debates, however, the televised debates of 1976 took place before a live audience. This innovation prompted objections from President Ford’s political advisers and was the subject of its own debate. The President’s legal advisers pointed out that a live audience was needed to lend credibility to the argument that the debate was a bona fide media event and, therefore, not subject to the equal time requirement. However, the candidates’ representatives, with the consent of the League, succeeded in preventing the networks from showing audience reaction. The only shots of the audience permitted in 1976 were those taken before and after the debates, much to the displeasure of network management (Kraus 1988, 42–44).

During the 1980 presidential campaign, there were two televised debates, one between Republican candidate Ronald Reagan and John B. Anderson, a minor party candidate, and the other between Reagan and Democrat Jimmy Carter, the incumbent president.

In the spring of 1979, the League of Women Voters was assured by the Republican and Democratic national committees that it would be allowed to sponsor and organize a series of televised debates to be held during the presidential election campaign that was to take place in the fall of 1980. In March 1980, the Federal Election Commission authorized groups like the League to collect funds from business, labour and charitable foundations to finance events such as debates between presidential candidates. In July 1980, League representatives asked journalists’ associations to provide a list of eminent journalists to participate in the debates as representatives of the media (Martel 1983, 7–8).

On 19 August, the League invited Reagan and Carter to take part in a series of four televised debates, the first of which would be held in Baltimore on 18 September, the second in Louisville on 2 October, the third in Portland on 13 October and the fourth in Cleveland on 27 October 1980.

According to Ruth Hinerfeld, president of the League at that time, the idea of having four debates was based on the 1976 experience, and the locations were selected based on geographic diversity and facilities that were available to the League (Martel 1983, 8).

In addition, as a token of its neutrality, the League insisted on allowing a minor party candidate to participate. To qualify, such a candidate would have to receive at least 15 percent in the polls by 10 September 1980. That candidate was John Anderson, who ran as a Republican in the primaries but as an Independent in the general election.

President Carter and his advisers refused to participate in the debate held in Baltimore on 21 September 1980 (it had originally been scheduled for 18 September) because the polls showed that Anderson’s entry into the race would draw votes away from the Democrats. The Democrats attacked the League’s credibility, implying that the debate between Anderson and Reagan was really a debate between two Republicans. This strategy on the part of the Democrats was designed to cast doubt on the neutrality of the League and the value of the debate (Martel 1983, 9).

In the fall of 1980, the American economy was stagnating and inflation was high. The American hostage situation in Iran was also doing nothing to improve President Carter’s standing in the polls. He therefore was not eager to meet Anderson and Reagan in a three-way debate.

In the days preceding the Baltimore debate, the League invited Carter and Reagan to a two-way debate to be held in the Public Music Hall in Cleveland, Ohio, on 28 October. After lengthy negotiations over a format that would satisfy the strategic interests of both candidates in a volatile political atmosphere, Carter agreed to debate with Reagan. The use of questions from journalists in the first half of the debate favoured Carter, who was better informed than Reagan, while holding the debate one week before the election favoured Reagan, who had a better television presence. Reagan’s ensuing victory in the televised debate was crowned by such rhetorical tactics as the use of “There you go again” when Carter tried to attack him. ABC took a telephone poll after the debate and confirmed the success of the California governor’s performance (Martel 1983, 27–28).

In 1984, the League of Women Voters again sponsored presidential debates and was heavily criticized, especially on the process for selecting journalists to make up the panel. Three debates were presented: the first took place on 7 October in Louisville, Kentucky, and dealt with economic and domestic political issues; the second, held in Philadelphia on 11 October, dealt with general topics; and the third, held in Kansas City on 21 October, dealt with foreign affairs and defence. Two of these debates were between incumbent President Reagan and Walter Mondale, while the Philadelphia debate pitted vice-presidential incumbent George Bush against Geraldine Ferraro.

The format of these debates was similar to that of previous debates: a moderator and a panel of journalists took turns asking questions of the candidates. Candidates were also given opportunities to refute their opponent’s answer.

When the debate format was under negotiation, the League submitted the names of 100 journalists from which the candidates’ representatives could select the panel. Despite their credentials, this list of journalists was rejected by the candidates’ representatives, who chose Barbara Walters of ABC as moderator for the Louisville debate and Diane Sawyer of CBS, Fred Barnes of the Baltimore Sun and James Wilghart of the Scripps Howard news service as panelists. For the vice-presidential debate held in Philadelphia on 11 October, the candidates’ representatives chose Sander Vanocur of ABC as moderator, and Robert Boyd of the Philadelphia Inquirer, Jack White of Time magazine and John Mashek of U.S. News and World Report as the panelists. For the final debate between Mondale and Reagan in Kansas City, Edwin Newman of PBS was moderator, and the panel consisted of Morton Kondracke of the New Republic, Georgie Ann Geyer of Universal Press Syndicate, Henry Trewhitt of the Baltimore Sun and Marvin Kalb of NBC.

For the first time, the League’s panelist selection process had been categorically rejected by the candidates’ representatives. The list of journalists submitted in 1976 by the League had been accepted by the candidates’ advisers as an inventory from which to make their selections; in 1980, the names of some journalists had been rejected, but the selection had been made from the list submitted by the League (Kraus 1988, 56–57).

Immediately after the 1984 presidential election, the two principal American parties declared that they were unhappy with the way the League of Women Voters had handled the debates, and decided in 1986 to create the Commission on Presidential Debates. This nonprofit organization, with a legal status similar to that of the League, included the heads of the Republican and Democratic national committees. In the two years leading up to the 1988 presidential election, the League of Women Voters attempted to argue that it was best suited to sponsor the debates because of its experience and nonpartisan nature. In the period preceding the negotiations for the 1988 presidential debates, representatives of the Republican and Democratic candidates presented a 16-page document establishing the rules, including such details as where the cameras could be placed and what portions of the stage could be shot. This document prompted such dissension among the members of the new Commission on Presidential Debates, the League of Women Voters and the television networks that the League was eventually replaced as the debate sponsor by the Commission on Presidential Debates (Interview, Sidney Kraus, 1991). Two debates were held in 1988 as part of the presidential election campaign.

According to Kraus, the negotiations surrounding televised debates in the United States are controlled by the candidates, who do not hesitate to threaten to pull out of the debates as an intimidation technique or to publicly embarrass the sponsors or the television networks when this type of tactic suits their purposes. Kraus, an expert on political debates in the United States, says that the candidates’ control over the negotiations enables them to shape the format in their favour, thereby projecting a more positive image of themselves and increasing their chances of winning the election (Kraus 1988, 64). He concludes that politicians should be removed from the debate negotiating process (Interview, Sidney Kraus, 1991).

In the United States, journalists play a major role in televised debates. Many experts believe that this limits the likelihood of direct confrontation between the candidates, who can simply confine themselves to answering the journalists’ questions. Some observers, such as Ranney (1979) and Salent (1979), have characterized the debates as “televised joint appearances” or joint news conferences at which the candidates simply answer questions from a panel of journalists. A study by Tiemens et al. (1985) showed a low level of conflict and contradiction between Carter and Reagan during the 1980 debate. According to the study, this lacklustre performance resulted from the debate format, which deprived the encounter of spontaneity and condemned it to sterility. However, the candidates prefer this format because it reduces the risk of direct confrontation, since there is always a danger that an aggressive approach will reflect negatively on the aggressor.

According to Kraus, debates could be made a regular feature of U.S. elections by amending the Federal Election Campaign Act of 1971 to require a candidate to participate in the candidates’ debate to qualify for the tax credits allowed under the Act. Candidates who refused to debate would thus be denied public funding (Kraus 1988, 154).

TELEVISED DEBATES IN EUROPE AND AUSTRALIA

Debates in France

The French televised debate format most closely approximates a duel or a direct confrontation. Journalists had little to do with two of the three debates between presidential candidates (1974 and 1988). They were therefore characterized as “stopwatch journalists” (Okrent 1988, 42) because they simply kept time and signalled changes in topics. Okrent notes that when journalists moderate and structure the debate, as was the case in 1981, more topics are covered than in the direct confrontation format where the candidates select the topics for discussion. However, in France, 69 percent of voters prefer a direct confrontation between the two candidates to a debate moderated by journalists (ibid., 41).

Under section 16 of the loi du 30 septembre 1986 (Act of 30 September 1986), the Commission nationale de la communication et des libertés (CNCL) is responsible for regulating the scheduling and broadcasting of election debates in France. This board has full powers to regulate radio, television and telecommunications, as well as advertising, including political advertisements. The CNCL was replaced on 17 January 1989 by the Conseil supérieur de l’audiovisuel (CSA), which retained the same powers except for telecommunications, which were removed from its jurisdiction.

These regulatory bodies were established to guarantee pluralism on the airwaves and ensure that all currents of opinion had access to the electronic media. Their mandate was to ensure balanced treatment of information by the electronic media, whether public or private. To this end, two principles have been established: before an election campaign, the Commission ensures that the principle of “equitable” access is adhered to following the “three-thirds” rule – one-third of air time goes to the government, one-third to the parliamentary majority and one-third to the parliamentary opposition. During the official campaign in the electronic media, which lasts two weeks, candidates must be treated equally. This equal-treatment principle takes priority over the editorial freedom of the electronic media. During the election campaign, the government agency determines the number and length of broadcasts and the scheduling of candidates on the publicly owned networks (Interviews, Francis Balle and Béatrice Jacomet, 1991). The CSA’s authority extends to presidential and legislative elections in France as well as to European elections.

In a decision made on 10 March 1988 (decision no. 88–73), the CNCL confirmed the established practice by limiting televised debates to the second round of presidential elections: “It [the televised debate] can take place only in the second round, providing both candidates agree. Half the total debate time is allocated to the time allowed each candidate” (France 1988, 3915).

Holding a televised debate before the first round of elections would be impractical, given the large number of candidates involved and the fact that the law requires that all candidates be treated equally. Therefore, televised debates in France are always held between the first and second rounds. This avoids the thorny issue of how many and which candidates will be allowed to take part in the debate because, under the French electoral system, only two candidates can be left by the second round.

In 1988, the televised debate was held on 28 April, 10 days before the vote on 8 May. It was telecast live over the national public networks TF1 and Antenne 2, and recorded for telecast over those private networks that opted to carry it. The moderators for the debate were the news directors of the two networks, Michèle Cotta and Elie Vannier. The debate was originally scheduled to last one hour and 50 minutes, but was extended by 30 minutes to comply with the rule guaranteeing the candidates equal speaking time, since one of the candidates had used more time.

According to a SOFRES (Société française d’études et de sondages) poll of 1 000 people taken immediately after the debate, François Mitterrand was the winner: 42 percent of the respondents thought that he had come out ahead, compared with 33 percent for Jacques Chirac. Eighteen percent felt it was a tie. A PSOS poll taken the day after the debate indicated that 55 percent intended to vote for Mitterrand, versus 45 percent for Chirac. A poll taken by the same firm on 24 April, four days before the debate, revealed that 53 percent intended to vote for Mitterrand and 47 percent for Chirac. The audience for the debate was estimated at 25 million, out of a total of 29 million eligible voters, making the election debate the most watched television show of the year. One can therefore conclude that the debate had some influence on voter intentions. Two important events occurred after the debate that also may have influenced the final result, namely, the release of three French hostages held in Lebanon and the violent resolution of a hostage-taking incident in New Caledonia. When the election was held, Mitterrand received 54.02 percent of the vote and Chirac 45.97 percent.

Two other televised debates in France, in 1974 and 1981, both featured Valéry Giscard d’Estaing and François Mitterrand. The first of these debates was televised on 10 May 1974. The rules for both debates were established by the Commission nationale de contrôle, which determined the permitted backdrops and camera angles. The latter were limited to long shots, medium shots and close-ups of each candidate. Cut-aways to show someone reacting or listening were not allowed.

In 1974, the two candidates agreed to a direct-confrontation format in front of two journalists, Jacqueline Baudrier and Alain Duhamel, who watched the dialogue between the two party leaders without asking any questions. Their role was simply to keep track of the amount of time each candidate spoke, using the two clocks in front of them with the candidates’ names on them. The topics for discussion and the order in which they would be discussed were not established in advance. The candidates alone controlled the debate.

The scheduled length of the debate was one hour and 30 minutes but was extended to one hour and 45 minutes as a result of the equaltime rule, since François Mitterrand had exhausted his time before Giscard d’Estaing. The ORTF (Office de radiodiffusion télévision française) estimated the audience at 23 million and noted a very high level of public interest (Cazeneuve 1974, 196; Nel 1990, 31).

In 1981, in an unusual step, the incumbent president sent a written invitation to debate to his challenger. Giscard d’Estaing evidently thought he had done well in the 1974 debate and wanted to repeat his strong showing. However, the invitation gave his opponent, Mitterrand, an opportunity to set the conditions. Mitterrand had not been well served by the 1974 debate format, which he described as a kind of political dogfight that was ill-suited to dialogue with the French people. For the first time in France, therefore, technical questions regarding the televised images were negotiated in order to bring the visual aspect of the debate under the equality principle as well. Restrictions were placed on the shooting and framing of images. For example, only medium shots and close-ups were allowed, while cut-aways and reaction shots were expressly prohibited: “Only the candidate who is speaking can be shown, and no cut-away shots or shots of the reaction of the opponent or of the referee will be permitted” (Nel 1990, 34). In this way, there is a sense of direct interaction with the public. Mitterrand understood that, in a televised debate, you have to convince not the opponent opposite you but the television viewer, who is not even present in the studio.

In his reply to Giscard d’Estaing, Mitterrand also objected to the 1974 debate format and demanded that journalists be present:

The key responses by each of the candidates, who may debate as much as they want in equal amounts of time, can only be given in answer to specific questions from competent observers in an atmosphere from which any element of sensationalism has been removed. I therefore tell you absolutely that either journalists and an independent producer will conduct the debate or there will be no debate. (Okrent 1988, 62)

The two representatives of the candidates and Jacques Boutet, the chairman of the Commission nationale de contrôle, negotiated the debate format. The one that was finally agreed on provided for a debate of one hour and 40 minutes on three topics: institutions and liberties, domestic policy, and foreign policy. The debate would be moderated by two journalists who would ask questions and control the amount of time allowed each candidate. The President of France was allowed to choose the journalists from a list of four names submitted by François Mitterrand. The two journalists selected, Jean Boissonnet of Europe 1 and Michèle Cotta of RTL, were chosen alphabetically, according to the President.

Both candidates based their communication strategy on the viewer. For Giscard d’Estaing, the purpose of the debate was to shed light on the choice that the French people were about to make, while Mitterrand suggested that it was to inform, to help people understand and to engage in dialogue with the nation.

The debate took place on 5 May 1981 as part of the official campaign, five days before the vote. It lasted 110 minutes, with each candidate allotted 55 minutes. According to Okrent, in 1981, 64 percent of the French public felt that the debate was the best way to learn about the candidates’ positions (1988, 139).

In France, there have also been televised debates between party leaders outside election campaigns. Raymond Barre met François Mitterrand on 12 May 1977 (Tarnowski 1988), Lionel Jospin met Simone Weil on 21 May 1984, and most recently, Prime Minister Laurent Fabius met RPR (Rassemblement pour la République) leader Jacques Chirac on 27 October 1985 (Champagne 1990, 169–91). Since these debates took place outside election periods, they were not subject to the equality rule and it was left to the discretion of the political parties and the networks to invite whomever they wished. The idea for the 1985 debate came from Laurent Fabius while appearing on the TF1 television program “L’heure de vérité.” These debates mainly serve the personal ambitions of the political leaders involved by increasing their popularity and improving their positions within their own parties (ibid., 185).

Debates in the Netherlands

Televised debates were introduced into Dutch political life in 1977, and were part of the 1981, 1982, 1986 and 1989 election campaigns. Debates are not governed by the electoral laws, but are handled instead by broadcasting associations, a type of viewer association peculiar to the Netherlands. Membership in these associations ranges from 100 000 to 500 000 people, and they are usually partisan (that is, they have a party affiliation). For example, there is VARA, an amateur radio association affiliated with the Labour party, and KRO, a Catholic broadcasting association linked to the Christian Democrat party. Protestants have an association, as do the Greens. Even apolitical viewers have an association, known as TROS. These organizations negotiate with the parties to determine a debate format. In practice, the liberal-minded associations representing the large Dutch political parties – PvdA (Partij van de Arbeid), CDA (Christen Demokratische) and VVD (Volspartij voor Vryheid en Demokratie) – cooperate in organizing the debate or debates and deciding who will participate. In this respect, the parties are not treated equally in the Netherlands since the large parties are able to take advantage of the situation and control the process at election time, at least for televised debates. As a result, there is a tendency to exclude the small parties on the extreme left or right. In addition, the debate format changes from election to election, depending on the balance of power among the parties.

In the first debate, in which Prime Minister Joop Den Uyl (PvdA) faced opposition leader Hans Wiegel (VVD), the two parties agreed to a format based on the American model. This agreement resulted in the following rules:

1. The debate was to cover six predetermined general topics, namely, unemployment, foreign policy, public security, education, housing and revenue policy.

2. The choice of the specific questions to be asked on each topic was to be left to a panel of three journalists, on whom the two parties agreed.

3. The speaker of the House of Representatives would act as moderator.

4. Unlike the American model, direct exchanges would be permitted between the two leaders. When a journalist asked the first question, the leader who had been selected in a draw to answer first would give his response. His opponent would then be allowed to respond, and so forth, with the questions being asked alternately of the leaders.

5. The debate was scheduled to last one hour and 40 minutes. (It actually lasted 11 minutes longer because the moderator showed some flexibility and allowed exchanges to run their course.)

The debate took place one week before voting day, 25 May 1977, and was seen by three million viewers out of a total population of 13 million.

A study of the impact of the debate compared the pre- and post-debate voting intentions of a small sample of people (312 before the debate and 280 after, including 235 who had been questioned before the debate). The study concluded that the debate had served primarily to reinforce partisan predispositions (De Bock 1978). Thus, 46 percent of the respondents felt that the PvdA (Labour party) representative had won, 26 percent felt that the representative of the right-wing VVD had won, and 6 percent had no opinion. The study noted that these results were highly partisan because 71 percent of the respondents who identified ideologically with the left thought that Den Uyl had won, while 69 percent of the supporters of the right thought that Wiegel had won. The debate, therefore, did not significantly influence the outcome of the election because only 2 percent of respondents said that the debate was the deciding factor in determining their vote, while 14 percent said that the debate had helped them decide. The debate seemed primarily to reduce the number of undecided voters, since the number who had no opinion about their attitude toward the government fell from 7 percent before the debate to 1 percent after, while the number who had no opinion about the opposition fell from 19 percent to 2 percent.

A large majority of respondents felt that the debate did not enlighten them significantly about party platforms (73 percent) or the leaders (69 percent). Paradoxically, however, 72 percent of respondents thought that holding the debate was a good idea.

Because the Netherlands has many political parties, a reflection in part of its electoral system of proportional representation, a single debate involving only the leaders of the two largest parties was seen as unfair to the smaller parties. The Dutch therefore experimented in the 1980s, holding several televised debates to allow all the parties represented in Parliament to take advantage of these opportunities. In 1981, there were three debates: one large debate on the eve of the election involving representatives of four parties (CDA, PvdA, VVD and D66, which is a left-liberal party), preceded by two other debates, one between the leaders of D66 and VVD, and the other between the leaders of CDA and PvdA. This format was repeated for the 1982 election.

During the 1986 election as well, several debates were held. The largest debate was televised on the eve of the election and involved the leaders of three parties: CDA, PvdA and VVD. Five days before the vote, two more debates were held, and these were organized along religious lines, since religion plays an important role in Dutch politics. Here, the representative of the Christian Democrat party faced first the leader of GPV and then the leader of RPF, both Protestant parties.

In 1989, only two debates were held. One featured the leaders of the two largest parties, CDA and PvdA, and was televised four days before the vote. The other, held on the eve of the election, featured the leaders of five parties – CDA, PvdA, VVD, D66 and the leftist Green party.

Journalists in the Netherlands play a role similar to that of their French colleagues. They moderate the candidates’ exchanges when necessary, apportion the amount of speaking time and introduce the topics for discussion. They rarely ask questions; the candidates pose most of the questions themselves.

The length of the debates varies. The major debates involving more than two leaders normally last two hours, while the smaller ones last 40 minutes. The candidates generally make a few opening remarks in which they outline their positions on issues that have been established in advance. Then they interact directly with one another. This format is similar to a round-table discussion.

The audiences for these debates in the Netherlands are small, compared with those in North America and France, where debates garner the attention of at least 50 percent of the electorate. According to polls taken in the Netherlands in 1981, only 25 percent of the respondents had seen the debates. This proportion rose in 1982 to 30 percent before falling again in 1986 to 25 percent for the major debate.

To gauge the impact of these debates, we consulted van der Eijk and van Praag (1987), who wrote the only book on this subject that has been published in Dutch. This study deals with the 1986 election and is based on a sample of 600 people living in the town of OuderAmstel, south of Amsterdam. The respondents were questioned twice, the first time 10 days before the vote and the second on voting day, before the results were known. The study concluded that the debates were not the reason for the victory of the Christian Democrats, who gained nine extra seats, increasing from 44 to 53 seats out of 150. There was no discernible difference in attitude between those who had seen the debate and those who had not. The authors discovered that the leader of the Liberal party, who was thought by most respondents to have won the debate, actually suffered the greatest losses for his party in the election. This study ran counter to the opinion expressed in most of the media that it was the performances of the leaders in the debate that explained the Christian Democrat victory.

Debates in Germany

In the Federal Republic of Germany, there were five consecutive debates before the Bundestag elections of 1972, 1976, 1980, 1983 and 1987. Paradoxically, the reunification of Germany prevented the holding of a televised debate before the last Bundestag election on 2 December 1990 because of the increased number of parties that could claim the right to participate in what is known as the “elephant round” of debates. The former Communist party, the East German PDS and the Alternative party (Alternative Liste) would have joined SPD (Sozialdemokratische Partei Deutschlands), CSU (Christlich Soziale Union), CDU (Christlich Demokratische Union Deutschlands), FDP (Freie Demokratische Partei) and the Green party in the debates. However, the main reason for not holding the debate was the popularity of the CDU-CSU coalition led by Chancellor Helmut Kohl. Moreover, Kohl had been annoyed during the 1987 debate by the Greens, whose representative, Ms. Ditfurth, had broken the rules of the debate by addressing her adversaries directly and had been particularly aggressive toward Chancellor Kohl. The official explanation advanced by journalist H.D. Lueg of the ARD network was that Chancellor Kohl wanted to stand in personally for cabinet minister Schaeuble at an election rally to be held on the day the debate was scheduled because Schaeuble had been the victim of a terrorist attack, which had caused an outpouring of emotion and compassion within the CDU (Interview, H.D. Lueg, 1991).

In Germany, the national television networks take the initiative in inviting the parties to a televised debate. Since the electoral laws do not require the electronic media to treat all the parties equally, the networks invite only representatives of parties with seats in the Bundestag, thereby giving them a degree of public legitimacy.

The first German experience with televised debates came in 1972 when, following the American model, three debates were organized and broadcast by the ARD network on 18 October, the ZDF network on 2 November, and by both networks on 15 November, four days before the election. The format for these debates varied. The first two debates lasted one hour each and journalists played a major role, asking questions of the party representatives and following up with additional questions. Thus the interaction was primarily between the journalists and the leaders, rather than between the leaders themselves. The third debate was different, first because it lasted two hours and second because the exchanges were solely between the leaders, since the moderators (W. Hubner of ARD and R. Woller of ZDF) confined themselves to apportioning the time equally between the leaders.

In subsequent elections, the format was again changed to provide for only one debate, to be held on the Thursday preceding election day. This makes it possible for voters to recall their impressions of the debate when they go to vote; in addition, there is little time for media pronouncements on the leaders’ performances to influence voters’ choices. The debates are televised by both national networks, ARD and ZDF. Some have lasted three hours or more, with the 1976 debate continuing for three hours and 45 minutes. Since 1983, however, the debates have been limited to two hours. The debates are hosted by journalists who act as moderators, guiding the discussion by asking questions and sometimes calming the participants. Neither the questions nor the topics for discussion are determined in advance, which leaves room for spontaneity. The editors-in-chief of the ZDF and ARD networks act as moderators. Except for the Greens, who have adopted a very aggressive stance, the party representatives are content to answer journalists’ questions without interrupting or attacking one another.

Unlike France, therefore, the debates in Germany do not resemble a televised duel. The party leaders have always been opposed to the French format, claiming that German elections are parliamentary in nature, not presidential, and that it is the parties that are being elected, not the chancellor. In addition, the existence of party coalitions, which are an integral part of the German political system in both the government and the opposition, would make it difficult to stage direct confrontations between the chancellor and the leader of the opposition party. However, the direct confrontation format is used in some of the Länder or German states. All parties with seats in the Bundestag are represented in the debates, so there were five participants in 1987. It is not necessarily the party leaders who participate in the debates, because sometimes a party’s candidate for chancellor is not the party leader, as was the case with Helmut Schmidt in the 1976 election. The Greens designated two representatives in 1987, a man and a woman, leaving it up to the networks to decide randomly who would participate.

Interest in televised debates is declining in Germany, judging by the percentage of eligible voters who watch them. This proportion fell from 84 percent in 1972 to 75 percent in 1976, 68 percent in 1980, 56 percent in 1983 and 46 percent in 1987. Despite this decline in voter interest, the debates remain major political events that are viewed by around half the German electorate. This audience still surpasses those for soccer games, which are extremely popular in Germany. The declining interest in the 1980s can be explained by the introduction of cable television and the proliferation of private channels competing with the public networks and depriving them of their monopoly. By the end of 1990, 4.5 million or 60 percent of West German homes were equipped with cable television.

In Germany, the debates influence voter attitudes. In a study comparing the responses of people who had seen televised debates with those who had not, Schrott (1990) showed that the debates affected how the public viewed the participants. He observed that people who had seen the debates had a more positive view of politicians. The debates also tended to work in favour of the incumbent chancellor, who was given a more positive rating than his opponent by those who watched the debate than by those who did not. “In West Germany … it is the challenger who constantly loses ground and the chancellor who appears to gain” (ibid.). German voters seem to give greater credibility to positive arguments than to critical attacks on an adversary (Baker et al. 1981, 541). The same phenomenon has been observed in some American debates (Stewart 1975).

Schrott also observed that being considered the winner of a debate had an influence on the subsequent vote and that this effect did not depend on one’s position (candidate for chancellor or simply an allied candidate): “Not only the chancellor and his challenger, but other participants too are likely to gain votes for their parties if judged as the winner. This indicates that the debates in West Germany are not simply a contest between the chancellor and his challenger but involve the other two participants equally strongly. A small party such as the FDP might gain substantially from its leader being the winner of the debate … No doubt, debates matter for vote choice in West Germany” (Schrott 1990).

Debates in Scandinavia

Televised debates in Scandinavian countries are part of political life, although their format varies from one country to another.

In Denmark, a three-hour debate among the leaders of all the political parties is broadcast on radio and television two days before election day. The event takes the form of a news conference with a time period allotted for the presentation of each candidate’s election platform.

According to Siune (1991), when the television broadcasting monopoly was broken in Denmark with the arrival of channel TV2, the rules of the game guaranteeing the presence of all the parties at the event were changed. The new channel held the debate the day before the election and invited representatives of only the most popular parties.

The Norwegian format differs from the Danish model, as the debate takes place in front of journalists or a group of voters who ask the candidates questions. For a Norwegian political candidate to participate in the televised debate, his or her party is expected to meet the following criteria: the party must already have been represented in the Norwegian Parliament during one of the last two mandates, must have fielded candidates in a majority of electoral districts and must have a national organization. An exception, however, is that a minority party that is a member of a coalition in power or that represents a credible alternative to the government may participate in the debate (Siune 1991).

In the parallel news conference format used in Sweden, party representatives meet two journalists 48 hours before the vote; the journalists take turns questioning the representatives on their policies. This approach is similar to an oral examination before the public, which acts as the jury. Any direct confrontation between the participants is avoided, with the result that these debates more closely resemble a news conference than a traditional debate. The event is televised in prime time on all the networks, which in Sweden are publicly owned.

In theory, only parties represented in the Swedish Parliament have access to the televised debates. Two minority parties not represented in the Parliament participated in the debates held during the 1988 election campaign, however, only because the Swedish broadcasting organization deemed that some of the issues in their election platforms were priorities for the election. Swedish radio and television broadcasting law gives broadcasting organizations the authority to decide who will participate in the televised debates (Siune 1991).

Debates in Australia

Televised debates in Australia are a recent innovation, with only two debates held so far during general elections. The first was in 1984, pitting Prime Minister Bob Hawke against the Liberal leader, Andrew Peacock. The two leaders met again in a debate during the 1990 election. According to Warhurst (1991), the 1984 debate was broadcast on all the stations in the country, while the 1990 debate was broadcast only on the Australian Broadcasting Corporation, Special Broadcasting Service and only one of the three private television networks. One study revealed that 56 percent of the Australian electorate listened to the 1990 debate (Lloyd 1990, 97). According to Lloyd, the impact of this event on voters was significant during the 1990 election campaign. Lasting 60 minutes, the 1990 debate had opening and closing remarks by the candidates and included a panel of journalists who asked the candidates questions. In addition, the leaders discussed election issues during part of this time, thus provoking heated exchanges (ibid., 5).

TELEVISED DEBATES IN CANADA

Debates during Federal Elections

In Canada, debates were held during the 1968, 1979, 1984 and 1988 elections, with a different format for each.

The 1968 Debate Format

The 1968 debate copied the parallel press conference format used in the United States. That year, the media took the initiative, calling for a televised debate when the election campaign was launched. Circumstances favoured the holding of such a historic event because both major party leaders were running for the first time in their new positions: Robert Stanfield of the Progressive Conservatives and Pierre Trudeau of the Liberals had been chosen leaders of their parties in the previous few months. They were therefore both eager to take up the challenge to make themselves better known to the Canadian public. Pierre Trudeau was considered the more telegenic of the two and was the object of a craze unique in Canadian politics, which journalists dubbed Trudeaumania. Stanfield had a less flamboyant style but was seen as a serious, honest politician.

The Progressive Conservative leader was the first to accept the debate proposal by the CTV and CBC networks on the condition that Prime Minister Trudeau not be accorded any special treatment. The debate had to be on equal terms. Stanfield had much to gain from a televised debate, which would attract a far larger audience than he could otherwise hope to reach.

Liberal strategists, on the other hand, were not so eager for a debate, feeling that the prime minister had the most to lose because he already enjoyed a strong lead in the polls. The May Gallup poll showed that 50 percent of decided voters intended to vote Liberal, 29 percent Conservative, 16 percent NDP and 5 percent for other parties (Gallup Report 1968). The negotiations were therefore difficult and dragged on from 30 April to 29 May 1968.

The Liberals faced a dilemma. How could they minimize the negative impact of a refusal to debate, or, if they ultimately felt obliged to agree to a debate, how could they minimize its risks? They therefore insisted on several conditions: the debate had to be carried by all the networks, it had to include the leaders of all five parties with seats in the House of Commons and it had to be bilingual.

CTV originally wanted a debate involving only the leaders of the two largest parties. There was little enthusiasm for handing the NDP a platform, not to mention the Ralliement créditiste. Also, the debate was to be in English only. This proposed format provided Trudeau with an opportunity to have his conditions accepted and thereby resolve his dilemma. He was adamant that all parties be included. This condition served two purposes: it reinforced his image as a democrat and, if his conditions were rejected, he could withdraw without losing face. Also, if smaller parties were allowed to participate, they would serve to divert attention, to dilute the confrontation between Trudeau and Stanfield, and lessen the risks of a poor performance. The prime minister also insisted that the debate be bilingual, because this was part of his vision of Canada and because it would distinguish him from his adversaries; the leaders of the Progressive Conservatives and NDP did not speak French.

The Progressive Conservative and NDP leaders, unable publicly to refuse a bilingual debate, demanded that simultaneous interpretation be available. Liberal strategists did not like this solution because it deprived Trudeau of the advantage of his bilingualism and could even detract from a clear understanding of his message. It seemed absurd to have his English-language statements repeated in French by an interpreter when he could do a better job himself in his own native tongue. Similarly, the Liberal leader could express himself in English far better than any interpreter. The cause of bilingualism was nonetheless deemed worthy of a concession to the Liberals’ political opponents and they finally agreed to a bilingual debate with simultaneous interpretation, in which each leader expressed himself in the language of his choice. However, party leaders were provided with a button which they could push to block the interpretation of their own statements in case they wanted to speak for themselves in both languages. Canada therefore innovated in the area of televised debates, not only by holding a bilingual debate but also by including four party leaders, the Liberals having dropped their initial demand for a round table of five leaders.

This left the thorny issue of the allocation of speaking time. For this first debate, it was decided that time would not be allocated equally. The Social Credit leader would be allowed to speak only in the final 40 minutes of the debate, giving the other leaders 80 additional minutes. However, what seemed to be a handicap turned out to be an advantage for Réal Caouette, who caught the interest of the viewers by enlivening the end of what had been a rather dull and tedious debate.

With his fiery style and colourful language, the Créditiste leader breathed new life into the debate (La Presse 1968).

The debate was televised from 9:00 PM to 11:00 PM on Sunday, 9 June, two weeks before voting day. To lend weight to the event, the studio was set up in the Confederation Room in the Parliament buildings where federal-provincial conferences were normally held. The co-producers of the telecast were Don Macpherson of CTV and Jim Shaw of CBC. The co-hosts were Pierre Nadeau and Charles Templeton, and the journalists were Jean-Marc Poliquin of Radio-Canada, Ron Collister of CBC and Tom Gould of CTV. Each leader was allowed three minutes for opening remarks. Each then had two minutes to answer a question from a journalist, which each of the other leaders was allowed to rebut for 90 seconds. A small light on each leader’s desk, which was also visible on television screens, came on 30 seconds before the end of his allotted time and began to blink when the time had expired. The moderator was responsible for allocating speaking time, taking into account interruptions caused by interpretation, which delayed the next speaker and slowed the pace of the debate.

The 1979 Debate Format

In contrast to the usual scenario, in which the leader of the opposition eagerly calls for a televised debate as soon as an election is called, it was he who was most reluctant in 1979. The Progressive Conservative leader, Joe Clark, had the most to lose under the circumstances because he had everything to prove, while the Liberal leader, Pierre Trudeau, had little to lose and the NDP could only gain from a television appearance by its leader, Ed Broadbent.

The Progressive Conservatives therefore would have preferred no debate at all. They dragged their feet during the negotiations and rejected the proposal of the three television networks for a 90-minute telecast involving the leaders of the Liberal, Progressive Conservative and New Democratic parties. The networks had decided to exclude Fabien Roy, the leader of the Ralliement créditiste, on the grounds that his party was running candidates only in Quebec and therefore had no chance of forming the next government. In addition, the Créditiste leader did not speak English, and no one seemed eager to repeat the 1968 experience of a bilingual debate.

To resolve the bilingualism problem and the unfairness of an English-only debate, Radio-Canada suggested that all the leaders, including Fabien Roy, participate in a round table where they would respond to successive questions in French from two journalists, without any direct exchanges between the leaders. The Liberals rejected this format, thereby depriving the French-speaking audience of a debate and prompting some political commentators to say that the Canadian duality was indeed two solitudes (Décary 1979).

At the outset of the negotiations, the Progressive Conservative strategists demanded that the debate take the form of a direct confrontation between Pierre Trudeau and Joe Clark, thereby excluding both the NDP leader and journalists. They hoped to capitalize on the debating skills of their leader, Joe Clark, who had succeeded in scoring points off the prime minister several times in the House. In the end, though, the Conservatives had to bow to the rules established by the networks because a refusal to participate in the debate would have lent credibility to the contention that their leader, who was already under attack from the media and the other parties, was a coward.

The CTV, CBC and Global networks had demands of their own, particularly regarding a livelier format allowing as many direct exchanges between the leaders as possible, which in turn would maintain audience interest. In the end a compromise was agreed on that, although not a direct confrontation between the two leaders, allowed more latitude than in 1968 when the leaders were confined to answering the journalists’ questions and were not allowed to address each other directly. It was decided to hold three direct confrontations in which the leaders would alternately face one another for 30 minutes, in the hope that this would lead to a livelier debate. The parties agreed as well that each leader would make brief introductory remarks for three minutes and concluding remarks lasting no longer than four minutes. The order of speakers was determined by a draw: Joe Clark was to start, followed by Pierre Trudeau and then Ed Broadbent. The reverse order would be followed for the concluding remarks.

David Johnston who, at age 37, had just been appointed President of McGill University, was chosen as moderator for his mediation abilities and political neutrality. To ease the formal structure of the debate, the moderator was given additional responsibility and room to exercise judgement. However, this new format made the journalists’ task more difficult because it was more ambiguous. Peter Desbarats, representing the Global network, expressed his confusion: “I’m a bit vague. I don’t think we’ll have the opportunity to ask anything very penetrating. The restrictions of format bother all of us. It’s not really a press conference kind of a thing” (The Gazette, 11 May 1979). The journalists, who considered themselves the representatives of the public, felt entitled to ask all the questions they wanted and even to contradict a leader if they believed he was wrong. Normally, journalists adopt a distant or critical stance toward politicians, based on the belief that their credibility will be damaged if they appear as mere sounding boards. However, the party representatives insisted that the journalists be limited to introducing the debate and that it was not their role to trade arguments with the leaders, since the leaders could do that among themselves. This approach was finally adopted, although in practice the moderator allowed several follow-up questions from the journalists and even had to reprimand them when they became too aggressive. Peter Desbarats, for instance, engaged in a lively exchange with the prime minister, who had accused the journalist of having misquoted him as saying that it was treasonous to support Quebec separatists. Desbarats replied, “He did use the word ‘treason.’ I was there. I heard it.” The prime minister also had a run-in with David Halton, who reminded him of a statement in Vancouver accusing the unemployed of being lazy.

The choice of political correspondents from the three networks for the debate (Bruce Phillips from CTV, Peter Desbarats from Global and David Halton from CBC) was accepted by all the participants, but was attacked by the National Action Committee on the Status of Women (NAC), which decried the lack of women on the panel. NAC also criticized the dearth of questions on issues of particular importance to women. To make up for this deficiency, NAC invited the three party leaders to take part in a forum on women’s issues, but the leaders declined (Rex 1979).

The 1984 Debate Format

The 1984 election marked a turning point in Canadian politics because the two largest parties had new leaders, each claiming to represent new directions, and because the election resulted in a political realignment that saw the Progressive Conservatives return to power after 20 years of Liberal rule. The Liberals had been returned to power in February 1980, after defeating the Progressive Conservatives in the House with the support of the New Democrats and the abstention of the Créditistes. (There were no televised debates in 1980 because Pierre Trudeau had refused to participate.)

The situation in 1984 was favourable, therefore, for the holding of a debate because there were two new party leaders who were interested in maximizing their media exposure. Further, the election was to take place in the summer and special events were needed to attract the attention of voters, since most would be on vacation during much of the election campaign.

As was to be expected, the Progressive Conservative leader took advantage of his first news conference after the election was called to challenge his opponents to a televised debate. In so doing, he took the wind out of the sails of NDP leader Ed Broadbent, who had been advised to take the initiative (MacDonald 1984, 287). Brian Mulroney was extremely eager to confront John Turner before the television cameras. “Just wait till I get Turner into a television studio,” he liked to say. “The voters will be able to see the difference for themselves” (ibid., 290). The Conservatives needed a debate at any cost to strengthen the image of Brian Mulroney, who was seen by the electorate, according to the Conservatives’ own polls, as less competent than the Liberal leader (Hay 1984, 13). Having thus taken the initiative, the Conservative strategists had no manoeuvring room and had to accept whatever conditions were laid down by the Liberal strategists.

A debate was also likely to benefit Ed Broadbent, even though there was a strong possibility that one would be held in French, because the leader of a smaller party always benefits from a televised debate in which he is treated as the equal of the other leaders and a credible alternative to the two major parties. Broadbent therefore declared that he was prepared to debate “any time, any place” (Globe and Mail 1984).

For the Liberal leader, the risks were greater than the potential benefits. First, his party enjoyed a 10 percent opinion-poll lead over the Conservatives. In addition, John Turner was ill at ease before the cameras after an extended absence from politics. During the leadership race he had seemed nervous and hesitant in answering journalists’ questions. His ticks, dry throat and rapid eye movements worried his advisers, who feared he might commit a serious blunder. He was, they thought, too “hot” for television (MacDonald 1984, 287). Finally, his French was still laboured and could place him at a disadvantage in a debate with the Progressive Conservative leader. It would be difficult for Turner to refuse to debate, however, without running the risk of even harsher criticism from the media and his political opponents, who would accuse him of disregard for the voters and a lack of leadership. Turner therefore agreed in principle to a debate to be held on 14 July, but the Liberals were then able to impose their conditions because the other two parties had already agreed to participate.

The Progressive Conservatives suggested five regional debates followed by a national debate. The Liberals rejected this format as too onerous for their leader, who was still the head of government running the daily business of the nation. It was therefore agreed to hold two national debates of two hours each, one in French and the other in English. The risks would therefore be reduced, because a poor performance by the Liberal leader in French could be offset later in the English debate.

The television network executives wanted a debate at the end of the campaign on 26 August, after vacationers had returned home and the audiences would be larger. The Progressive Conservative and NDP negotiators, Michael Meighen and Gerald Caplan, also wanted the debate to be held at the end of the election campaign, because the issues would then be known. The Liberal strategists rejected this argument, however, and insisted that the debates take place before 26 July, that is, early in the campaign, so that a possible poor performance by their leader would have less impact. At least this was the explanation offered by Gerald Caplan for the choices of 24 July for the debate in French and 25 July for the debate in English (Rusk 1984).

The parties agreed to return to the tried-and-true 1979 format, which included three direct confrontations of 30 minutes each in which each leader debated directly with the other two. Each leader would also have three minutes to make opening remarks and four minutes to sum up.

Lots were drawn to determine the speaking order. Brian Mulroney would open the French debate, followed by Ed Broadbent and John Turner, with the reverse order for the summation. For the English debate, Broadbent drew the opening position, followed by Turner and Mulroney. The order for the one-on-one confrontations was the following: in French, Turner and Mulroney would face each other first, followed by Turner and Broadbent, then, finally, Mulroney and Broadbent. In the English debate, suspense would be maintained until the end, because the first half-hour featured the Broadbent-Tumer debate, the second round the Broadbent-Mulroney debate, and it was not until the final round that Mulroney would meet Turner.

The choice of moderators and journalists did not pose any particular problems. For the former, well-known academics were selected to ensure a serious, objective, credible telecast. David Johnston, President of McGill University and moderator of the 1979 debate, was chosen to moderate the English debate. It was agreed that Raymond Landry, Dean of the Faculty of Civil Law at the University of Ottawa, would moderate the French debate. The English networks selected David Halton of the CBC, Bruce Phillips of CTV and Peter Trueman of Global to ask questions, while the French networks chose Jean Paré, editor of the newsmagazine l’Actualité, Luc Lavoie of TVA and Louis Martin of Radio-Canada.

The debates were to be taped at the studios of CJOH in Ottawa using the same set that had been used in the 1979 debate. For the French debate, Turner would stand in the middle, flanked by Mulroney on the right of the television screen and Broadbent on the left. In English, Broadbent would stand in the middle, with Mulroney on the right and Turner on the left. The French debate would be televised on 24 July from 8:00 PM to 10:00 PM, and the English debate, the next day from 9:00 PM to 11:00 PM.

In addition to these negotiations, NAC demanded that a third debate be held on women’s issues. Once again, the leaders of the two opposition parties agreed without hesitation, while the prime minister took several days to respond. Turner had an image problem with women voters as a result of the “tactile politics” incident in which he patted the posterior of the female party president, and he would have only aggravated the situation by avoiding questions on women’s issues. He agreed, even though he had said earlier that his schedule would enable him to participate in a maximum of two debates.

The debate on women’s issues took place in Toronto on 15 August. In contrast to the format for the national debates, this event more closely resembled a parallel press conference than a true debate. There was also a live audience that openly demonstrated its reactions, usually in support of the NDP leader. The debate was chaired by another academic, Dr. Caroline Andrew, Professor of Political Science at the University of Ottawa.

The 1988 Debate Format

Since the Canada Elections Act does not cover the organization of debates, the political parties and television network executives renegotiate for each election the format to be used. This process gives rise to a lively debate about the debates, with each party trying to outdo the others in issuing statements and blaming the other side for holding up negotiations over various aspects of the debates: dates, length, number and format.

It is not surprising, therefore, that discussions surrounding the format of the 1988 debates were soon overshadowed by a dispute between the party strategists, trying to take advantage of the media interest to curry favour with the public. These rivalries would not exist if the parties were not convinced that voters are extremely interested in the debates as an instrument of democracy and that there is a political price to be paid for being perceived as reluctant to debate. Martel calls this the “meta-debate” period and considers it to be a psychological war involving candidates and party strategists before the televised debates are held (Martel 1983, 151–65; Bernier 1991, 140–42).

In 1988, neither the leader of the party in power nor the leaders of the opposition parties rejected out-of-hand the idea of holding a televised debate. The precedent set by the 1984 debate in which the leaders all recognized the importance of a debate for the democratic process could not be ignored. In addition, despite the Progressive Conservatives’ comfortable lead in the polls, the volatility of the Canadian electorate was such that all parties could reasonably expect to make gains. Most important, there was the question of free trade, which deeply divided the Canadian electorate and was serious enough to warrant a public debate of its own. In an election that had the aura of a referendum and was crucial to Canada’s future, a leader’s refusal to debate would have had disastrous consequences for his party.

A few weeks before the campaign began, Brian Mulroney had said that he would be willing to participate in a televised debate under two conditions: that there be only two debates and that they take place early in the campaign, on 15 and 16 October. These types of demands seem to be a constant for the leader of the party in power, because Turner had adopted the same position in 1984. In addition, the Conservative leader did not want to repeat the experience of a single-issue debate, like the 1984 debate on women’s issues, and he steadfastly refused any suggestion of a debate devoted solely to free trade.

The leaders of the Liberals and NDP continually badgered Mulroney about the number of debates, insisting on the need for a debate on free trade. John Turner denounced the obstinate refusal of the Conservatives as cowardice, and suggested that Mulroney was refusing because he did not have any confidence in the agreement and did not want the Canadian people to gain a better understanding of its implications (Howard and Waddell 1988). The two opposition-party leaders also proposed a debate devoted exclusively to women’s issues. Ed Broadbent wanted four debates of 90 minutes each, claiming that the three-hour format suggested by the Conservatives would be too long for Canadians.