The Battle of Washington Square Park

Jane Jacobs left the offices of Architectural Forum, took the elevator to the lobby of Rockefeller Center, and pulled out her bicycle for the ride home to Greenwich Village. She pedaled across Forty-second Street and all the bustle of midtown Manhattan, past the Empire State Building and the big Macy’s department store at Herald Square, her handbag in a basket on the front handlebars. As she entered Chelsea, below Twenty-third Street, and then the Village, the buildings became lower, and the streets went from smooth pavement to rough cobblestones. She dismounted at Hudson Street and walked the bike up to No. 555.

Flipping through the mail, she came across an envelope that read, “Save Washington Square Park.” She’d read in the newspaper that the park was under threat. The parks commissioner, Robert Moses, planned to put a roadway through it, cutting it in half—and Moses had a reputation for getting things done.

The letter inside, from a citizens’ committee to save Washington Square Park, described the proposal. In its current form, Fifth Avenue, New York’s grand boulevard, stretched from Harlem all the way to Washington Square Park, but then ended abruptly at the park’s signature arch. A carriageway there allowed city buses to turn around and swing back up Fifth Avenue, which was a two-way street in those days. The Moses proposal was to extend Fifth Avenue straight through the park, Jane read. It would punch through to the south side and continue on into lower Manhattan as Fifth Avenue South.

The Fifth Avenue extension was a critical piece of Moses’s larger vision for Greenwich Village, one of a dozen areas in the city he had targeted for urban renewal—essentially wiping out sections of the old, cluttered neighborhood and putting in new, modern construction and wider streets. As chairman of the mayor’s Committee on Slum Clearance—a position he held simultaneously with that of parks commissioner—Moses was in the process of razing ten city blocks between the park and Houston Street to the south.

That area was a typical Greenwich Village neighborhood of five-and six-story buildings predominantly housing immigrants and low-income families, warehouses, and struggling manufacturers such as hatmakers. After World War II, the area had become threadbare and unkempt, with shabby building fronts and deteriorating interior conditions. Moses had designated it as a blighted slum, initiating an urban renewal plan that called for massive demolition to make room for giant towers containing some four thousand apartments, including rooms that could be rented for a low rate of $65 a month. The buildings, known as superblocks, would be set in open space, obliterating the existing network of small streets. In the first phase of the project, in which Moses would build a new housing complex called Washington Square Village, 130 buildings would be smashed by wrecking balls, and 150 families would have to pack up their belongings, leave their homes, and either apply for the new housing if they could afford it or find new places to live on their own.

The roadway through Washington Square Park would be not only a new gateway to Washington Square Village but part of Moses’s larger effort to replace the crazy quilt of streets in the area, which had their origins in the days of Dutch and English settlement, to accommodate the automobile age. An extended Fifth Avenue would speed the flow of traffic in the area all the way to yet another roadway Moses had proposed: the Lower Manhattan Expressway, a crosstown highway that would provide speedy east-west travel between the Hudson and the East rivers. It all worked together as a package: a modern road network and massive redevelopment. The project was all the more important because its success would signal to other neighborhoods the way of the future. Washington Square Park was in the way.

Jacobs, who had researched urban renewal for her articles in Amerika magazine, knew there was federal muscle behind the Moses plans. The federal Housing Act of 1949 provided millions in federal funding, as a kind of Marshall Plan for cities, and the superblocks of regimented housing towers were already replacing old neighborhoods in New York City—from Harlem to the Lower East Side—and in Boston, Philadelphia, Chicago, and St. Louis as well. Now Washington Square Park was being drawn into the transformation.

Like her Greenwich Village neighbors, Jacobs loved the park. It was, as Henry James had put it, a place of “established repose,” an oasis amid the concrete, bricks, and asphalt of the city. Ten years earlier, she had lived just a block west of the park, at 82 Washington Place, a stately apartment building that had been home to Richard Wright and Willa Cather, who described the parks charms in “Coming, Aphrodite!”: the fountain gave off “a mist of rainbow water … Plump robins were hopping about on the soil; the grass was newly cut and blindingly green. Looking up the Avenue through the Arch, one could see the young poplars with their bright, sticky leaves.” In those days, Jacobs would emerge from the big building and look to the right and see the comforting sight of the trees and the fountain and the statue of Giuseppe Garibaldi, the Italian national hero. After she moved a few blocks over to 555 Hudson Street and started her family with Robert, she began to appreciate the park as a mother. Through the early 1950s, she brought her sons to the play areas or strolled around with them under the dappled canopy of trees.

As Jacobs knew from her research on the area for articles for Amerika, many before her had been fiercely protective of the space. In the late nineteenth century, a group of residents in the homes around the park fought off a proposal to locate a sizable armory there. Later, the neighbors rose up in rebellion when the city had the audacity to propose an iron fence around its perimeter.

Though it had its formal elements, like the arch and the neat rows of homes with their identical stoops on the north side, Washington Square Park was never just a showpiece, meant to be seen but not touched. The people of Greenwich Village liked its worn-in, comfortable character. It needed no dressing up, as it was a place steeped in history. Henry James, Edith Wharton, Walt Whitman, Edgar Allan Poe, Stephen Crane, and Willa Cather were drawn there. Then the artists Willem de Kooning, Edward Hopper, and Jackson Pollock frequented its grounds, and later the beat writer Jack Kerouac and the folksingers Bob Dylan, Joan Baez, and Peter, Paul, and Mary. A young man named Ed Koch, later the mayor of New York, would come down to strum a guitar by the fountain. Home to protests, marches, riots, and demonstrations, the park had come to symbolize free speech, political empowerment, and civil disobedience. Downtown businessmen marched through it, clamoring for new silver and gold currency standards; women held a solemn vigil there after the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire killed 145 workers in 1911. It was a park where New Yorkers both turned their faces to the sunshine and looked inward to their conscience.

Some of New York’s most august institutions were located all around the park—Macy’s and Brooks Brothers, social clubs like the Century Association, opera and theater that was the precursor to Broadway, the New York Times before it moved to Times Square, grand mansions and town homes before there was such a thing as the Upper East Side, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Whitney Museum before they were moved uptown. The incubation of one of the world’s great cities occurred within a walk of this park.

But most of all, Washington Square Park was a place to be outside and to run around amid green grass and trees, in the middle of a city that could feel very paved and gray. In the 1950s, hundreds of thousands of Americans were leaving cities for the suburbs, preferring a house with a backyard, a place to throw a football or set up a swing set. But for most city dwellers, their only backyard, the only place they could let their kids be outside, was the neighborhood park. For anyone within walking distance in Greenwich Village, Washington Square Park was that place. It was the model for Central Park—the basic idea that people living all around a big park should be able to walk to it and stroll around a green space in the city, as a matter of public health and sanity—and as such, as vital a piece of urban infrastructure as any bridge or expressway.

Now one man was threatening it all—the history, the stewardship, the respite—and Jacobs was furious. She talked it over with her husband, who was equally dismayed at how the roadway would split the park down the middle. Moses had promised there would be extensive new landscaping on either side of the roadway, but there was no getting around the fact that green space and playgrounds would be replaced with the harsh formality of bituminous stone curbing. Bob’s sense for design, as a trained architect, led him to believe the park would become wasted, unused, or derelict space. Nobody would want to go there to be beside a highway. “Moses’ temple to urination,” he remarked, and Jane laughed.

Not content to merely send in the form letter the save-the-park committee had provided, Jacobs wrote a note in longhand dated June 1, 1955, to Mayor Robert Wagner and the Manhattan borough president, Hulan Jack:

I have heard with alarm and almost with disbelief, the plans to run a sunken highway through the center of Washington Square. My husband and I are among the citizens who truly believe in New York—to the extent that we have bought a home in the heart of the city and remodeled it with a lot of hard work (transforming it from a slum property) and are raising our three children here. It is very discouraging to do our best to make the city more habitable, and then to learn that the city itself is thinking up schemes to make it uninhabitable. I have learned of the alternate plan of the Washington Square Park Committee to close the park to all vehicular traffic. Now that is the plan that the city officials, if they believe in New York as a decent place to live and not just to rush through, should be for. I hope you will do your best to save Washington Square from the highway.

Respectfully,

Jane Jacobs

(Mrs. R. H. Jacobs Jr.)

Jacobs also filled out the form letter for the Washington Square Park Committee, checking off her opposition to a four-lane roadway and supporting closing the park to all traffic except for a bus turnaround. In that moment, Jacobs began her journey not just as a writer about cities or as a mother of young kids, but as a New York City activist.

For such a contested piece of real estate, Washington Square Park is simple—almost ordinary—in appearance. It is dotted by buttonwood and elm trees with muscular, drooping branches and peeling bark, including an English elm in the northwest corner believed to be the oldest in New York City. Benches bend along the gentle curve of the walkways. The arch, a sturdy structure reminiscent of the Arc de Triomphe in Paris, was added in the middle of the northern border to honor George Washington’s centennial as the nation’s first president. A fountain, built in 1856, was in a quirk of the layout set slightly off to the side, rather than being directly in line with the terminus of Fifth Avenue. Around the fountain were playgrounds and walkways, places to let a dog run around, and spots for musicians and street performers. But it had no special gardens like the Tuileries in Paris, no uncommon flowers or plants. The playgrounds were unremarkable. Still, the park felt comfortable and safe. It was cozy and well framed, lined with brownstones, town houses, churches, and university buildings. Arriving at the base of Fifth Avenue was “as if the wine of life had been poured for you, in advance, into some pleasant old punch bowl,” wrote Henry James, author of the nineteenth-century novel that invokes the park’s name.

A casual observer might think the whole area was carefully planned. Its basic parameters were the result of intentional urban design, based on the London residential square model from the eighteenth century. But Washington Square Park has a tumultuous history that suggests a kind of accidental public space.

It started, like everything in Manhattan, as a pristine natural area. Before the Dutch arrived, there were peat bogs, pine barrens, eelgrass meadows, and estuaries. Washington Square Park was a mushy bowl between the jagged hills of northern Manhattan and the bedrock close to the surface around modern-day Wall Street. A trout stream ran through it—called Minetta Creek, a snaking waterway through the reeds and cattails—and still does to this day, under the streets, nurturing the greenery above. The Lenape people, the Native American tribe that inhabited New York, hunted waterfowl even as the first fur traders from the Dutch West India Company settled on the southernmost tip of the island. Only after African slaves started arriving did the city begin its inexorable march northward, as farmland was needed to sustain the colony of New Amsterdam. The homes built in what is now Greenwich Village, referred to by the Dutch as Noortwyck, were first abandoned due to conflicts with the Lenape, but reclaimed when the Dutch freed numerous slaves and gave them land for farming and for raising livestock. Although the Dutch and then the English would later take the land away from them, freed African slaves were the vanguard that led to the permanent settlement of Greenwich Village all around Washington Square Park.

After the British took over in 1664, and renamed the city in honor of the Duke of York, the center of commerce remained in lower Manhattan, but English military officers built large homes to the north, in the countryside that reminded them of Greenwich, England. The name stuck, and the area was the city’s first pastoral retreat. Wealthy Americans took over after the Revolutionary War, settling into country estates amid the fields and fresh breezes. The spot that became Washington Square Park remained undeveloped, but it wasn’t a park from the beginning. It was a graveyard.

At the end of the eighteenth century, the city was in the grip of a yellow fever epidemic, and officials needed a place to bury the poor people dying monthly by the dozens. When the site of Washington Square Park was designated as a burial ground, surrounding estate owners, including Alexander Hamilton, tried to fight off the proposal. Despite their protests, the public cemetery was established in 1801 and adorned with a fence, trees, and other plantings. It is believed that some twenty thousand bodies remain under the park, and bones and skeleton-filled underground chambers have periodically turned up during construction and utility excavations.

The area was also used as a public gallows—leading the big English elm at the northwestern corner to be called the “hanging elm,” though no records exist of an execution from its limbs—and a dueling ground. It would have remained as such were it not for Philip Hone, a wealthy military hero from the War of 1812 who became mayor of New York in 1826. Hone sought to model the area after the successful squares of London’s West End, around which property values had soared. He launched a campaign for a military parade ground at the site, winning approval in time for a fiftieth anniversary celebration of the signing of the Declaration of Independence, when the square was officially renamed in honor of George Washington. Afterward, Hone expanded the park from about six acres to its current size of ten. Upscale residential development reminiscent of London and Philadelphia, which was already building neat lines of Greek Revival redbrick homes around places like Rittenhouse Square, started going up all around Washington Square Park.

From 1830 to the turn of the century, the neighborhood around the park was the most desirable in New York; this was where the Taylors, Griswolds, and Johnstons all flocked, aristocratic families that had lineage going back to the Mayflower. Later, it was the Vanderbilts and Astors, whose lavish parties and costume balls prompted Mark Twain to call the materialistic post–Civil War era the “Gilded Age.” All the while, a community of the arts and letters grew up around the square. Edgar Allan Poe had an apartment nearby and read “The Raven” in a rich benefactor’s parlor; Winslow Homer bathed canvases in brooding darkness and glowing light in a studio around the corner.

In 1870, under the direction of Tammany Hall’s leader, William “Boss” Tweed, the city embarked on a major campaign to overhaul all its existing parks, after a building spree that included Bryant Park behind the New York Public Library, Prospect Park in Brooklyn, and the 843-acre Central Park designed by the landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted. Smaller, older public spaces deserved a face-lift, City Hall decreed, and a Viennese landscape designer named Ignatz Anton Pilat was commissioned to give Washington Square Park new gardens and gaslight lampposts. Pilat, who replaced straight lined walkways with Olmsted’s signature curves, trying to evoke the expansive countryside in the middle of the city, also added the carriageway that would be the precursor to Moses’s road.

Though the park was by this time no longer officially a parade ground, military officials in the National Guard still sought to make a piece of the park their own. In 1878, they proposed the construction of an armory—the giant storage facilities for weaponry and supplies and mustering places for soldiers that were going up in cities all across the country. Wealthy residents including Thomas Eggleston and Samuel Ruggles, who was instrumental in creating Gramercy Park a few blocks to the east, successfully petitioned against the plan. Ruggles formed the first citizen-based organization to keep the city’s park safe from development, the Public Parks Protective Association, and in 1878 the New York state legislature passed a law keeping Washington Square Park for use “in perpetuity for the public as a public park, and for no other purpose or use whatsoever.” The tradition of stewardship began.

The park got its signature arch at the end of the nineteenth century. City officials were planning the centennial of George Washington’s presidency, and William Rhinelander Stewart, a neighborhood resident and a scion of one of New York’s Knickerbocker families, led a fund-raising campaign to build an arch in honor of the founding father. McKim, Mead & White, the Beaux Arts architects of Columbia University’s campus and Pennsylvania Station, designed a classical Roman monument of bright Tuckahoe marble seventy-seven feet high, bathed in electric light, with intricate inlaid panels in the vaulting underside of the arch, two statues of Washington topped by elaborate medallions on each soaring column, and an eagle set in the middle of its sturdy and ornamented cornice. Positioned at the foot of Fifth Avenue exactly in the middle of the north side of the park, the arch reflected the grandeur of London and Paris and was instantly a postcard image of New York and Greenwich Village.

The monumental city, however, was also the city of the desperately poor, and Washington Square Park was no exception. Despite the grand designs and the staggering wealth of the estate owners all around, the park was never the exclusive front yard for the well-off. Nor was it ever gated off as a private space, as Gramercy Park would become. Starting early in the nineteenth century, tramps and prostitutes were as common a sight there as promenading swells. Its central location also made it a popular spot for agitated New Yorkers of all kinds to hold protests, vigils, and demonstrations. In 1834, stonecutters unhappy with New York University’s decision to use prison labor for the marble fixtures for its campus buildings fanned out around the park smashing windows and marble mantels. Fifteen years later it was the Astor Place Opera House riot, pitting English against Irish. Then came the draft riots of 1863, when predominantly Irish laborers roamed the streets around the park, cutting telegraph lines and beating and killing black men. Suffragettes and veterans of the Spanish-American War marched through. There was no such thing as trespassing there. It was a place to which people of all classes and political persuasions came to express themselves.

At the turn of the twentieth century, Greenwich Village became a magnet for rebellious artists, painters, writers, and social commentators. Walt Whitman and the newspaper pioneer Horace Greeley were in the vanguard, hanging out at the nearby beer hall Pfaff’s. Stephen Crane, Theodore Dreiser, the journalist Lincoln Steffens, Marcel Duchamp, Man Ray, and an invasion of artists and intellectuals followed, crowding into flats in three-and four-story redbrick buildings, setting up studios around the square, playing chess in clubs, reading poetry at cafés and bars like the Brevoort and the Golden Swan, and dining at restaurants reminiscent of the Left Bank in Paris—the Pepper Pot, Polly’s, the Red Lion, the Russian Tea Room, and Samovar. Intellectuals banded together and started theater houses for the plays of Eugene O’Neill, another Village resident, and ran bookstores out of ground-floor space filled with both James Joyce and local literary journals produced a few blocks away. Poetry readings, the tango, player pianos, fashion shows, masquerade balls, and lectures and symposia filled the days and nights of Greenwich Village around Washington Square Park—a rival in many ways to Paris before and after World War I, as a capital of culture and new thinking.

Let’s settle down in Washington Square,

We’ll find a nice old studio, there.

…

We’ll be democratic, dear,

When we settle in our attic, dear,

In Washington Square.

So went the 1920 Cole Porter song “Washington Square.” The park became the leading character in poems, short stories, paintings, plays, and films. “Nobody questions your morals, and nobody asks for the rent. There’s no one to pry if we’re tight, you and I, or demand how our evenings are spent,” wrote the dashing Harvard-trained writer and poet Jack Reed, whose associates included Walter Lippmann and Lincoln Steffens. Sympathetic landlords put up with missed payments by the struggling artists and writers; one boardinghouse on the south side of the square was home to so many it was dubbed the House of Genius.

The Village continued its spirit of rebellion through the Roaring Twenties and Prohibition and was, naturally, the site of several infamous speakeasies. In the Great Depression, the liberal political leanings of Greenwich Village lurched toward radicalism. Independent journals like the Masses began publishing there, supporting workers and antiwar sentiment, drawing the attention of federal investigators for communist sympathies. Meanwhile, contemporary artistic movements including abstract expressionism were flourishing; the painters Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning, and Edward Hopper began their march to fame. The Whitney Museum of American Art on Eighth Street gave the art a place to be viewed; the theaters and cafés let people hear new plays and poems. Soon there were more artists than immigrants in Greenwich Village, painting, fashioning stained glass, or sculpting clay and marble.

At the same time the starving artists were doubling up in cold-water flats, upper-middle-class families and professionals flocked to the neighborhood, and real estate boomed around Washington Square Park. High-rise apartment towers began going up at the base of Fifth Avenue, towering over the north side of the park. New subway lines were being built nearby. New York University moved ahead relentlessly with plans for massive new campus buildings lining the square. And Greenwich Village became a tourist attraction, with busloads of visitors coming to gawk at the crazy, creative lifestyle of the bohemians and soak up the atmosphere at the jazz clubs and Left Bank–caliber restaurants.

Into the 1950s, as the beat writer Jack Kerouac, the poet Allen Ginsberg, the jazz musicians Charlie Parker and Thelonious Monk, and folksingers like David Sear all came to inhabit the cafés and clubs and studios and apartments of Greenwich Village, Washington Square Park shed the formality of the Henry James era and became a comfortable old living room, like the inner chambers of cafés on MacDougal Street. The street furniture got vandalized, the lawns turned brown, and the fountain basin leaked.

As an urban historian, Jane Jacobs appreciated the extraordinary evolution from cemetery, gallows, and dueling ground to a setting for Victorian promenades and classic Beaux Arts monumentality to an outdoor rendezvous for Pete Seeger, Woody Guthrie, and Bob Dylan, and on into the age of Aquarius. Hoop dresses to black jeans: that was the power of a place that was unplanned and organic. It was everything that was proper and respectable and aristocratic about New York City life—and at the same time it represented rebellion against the establishment, authority, and order.

The man from Oxford and Yale didn’t quite see it that way. This park needed a shave and a haircut, and to find a steady job. It needed to knock it off with the poetry readings and start serving a practical function for the city again—as a crossroads for the modern city.

The space that the residents of Greenwich Village viewed as comfortable and unpretentious was to Moses another city park that had fallen into disrepair. The plantings had withered, and the benches were broken or sagging. Moses cited this decline as a rationale for major changes. Like so much of the city, Washington Square Park needed to be upgraded and modernized. Sketching out his plans on yellow legal pads, Moses, as parks commissioner, first proposed a complete redesign in 1935, allowing vehicles to go around a new, oval-shaped layout in a giant traffic circle. The four corners of the park were to be rounded off, shrinking the ten acres of open space; the fountain was to be torn up and replaced by a central strip of gardens and pools.

The development around the park after the turn of the century had spawned several neighborhood groups—the Greenwich Village Association, the Washington Square Association, and the Fifth Avenue Association (the latter two having merged in 1926 to form the Joint Committee for the Saving of Washington Square)—which pleaded for building preservation and zoning changes that would slow down the large-scale development. In reaction to Moses’s 1935 redesign, they consolidated their efforts into the single Save Washington Square Park Committee.

Moses quickly recognized he needed to deal with the neighborhood opposition, just as he had done with the Long Island estate owners attempting to block his parkways there. His strategy was similar: portraying the opponents as not-in-my-backyard elitists, standing in the way of progress. But he took his tactics one step further—threatening to withhold all improvements if the Greenwich Village residents would not cooperate. He declined an invitation to appear before the Greenwich Village Association to explain his plans, instead dashing off a sarcastic letter to the group:

You will be glad to hear that the reconstruction of Washington Square Park is going to be left to posterity, and that contrary to what appears to be prevailing local opinion, we have not decided on any drastic changes—although we have been studying the future of this square from every point of view. We plan only to restore and improve the square now, without changing its present base character and design. There are all sorts of people around Washington Square, and they are full of ideas. There is no other section in the city where there are so many ideas per person, and where ideas are so tenaciously maintained. Reconciling points of views … is too much for me. The filling in of Orchard Beach in the Bronx, the development of Jones Beach or of Marine Park in Brooklyn, and the building of the Triborough and Henry Hudson bridges, are child’s play in comparison.

In 1939, Moses returned with a new plan, essentially the same proposal for a one-way roadway around the park, snipping off all four corners and adding a lily pond in a long strip in the center. Henry Curran, a resident and former deputy mayor, said that the oval Moses was proposing to replace the rectangle of Washington Square Park looked like a “bathmat.” The name stuck, much to the parks commissioner’s dismay. In the face of growing opposition, Moses again warned the residents that if his scheme did not go through, Washington Square Park would sink to the bottom of the city’s list for improvements of any kind. The neighborhood would lose out on millions in New Deal funding and labor that would go someplace else.

The threat had an immediate effect. John W Morgan, president of the Washington Square Association, initially opposed the “bathmat” scheme, but others in the organization supported it as an acceptable trade-off for badly needed upgrades—and for redeveloping the area south of the park, which by the 1930s had become tawdry. The group grudgingly supported Moses’s vision, by one vote. But a faction splintered off and collected thousands of signatures against it. Outraged by what they viewed as a cave-in, the members of the Volunteer Committee for the Improvement of Washington Square Park argued that the park would be turned into a speedway, endangering students and mothers with children.

A group of New York University students protested any changes to the layout of the park, claiming that pedestrian safety would be threatened. They were also worried about university tradition: the statue of the Italian patriot Garibaldi was the site for hazing freshmen and sophomores. The students and the Greenwich Village residents who remained opposed to Moses combined to create a powerful lobbying force directed at the Board of Estimate, New York’s powerful governing body of the time, which needed to approve the redesign. One member of the board, the Manhattan borough president, Stanley Isaacs, who had tangled with Moses over the Brooklyn-Battery Bridge, announced that there was insufficient neighborhood support, and the bathmat plan was put on the shelf.

With the onset of World War II, many of Moses’s public works ground to a halt, and the master builder backed off on the Village and its park—but not before taking several parting shots, which clearly reflected an impatience with not getting his way.

“It seems a shame you should suffer because of some stuffy, arrogant and selfish people living around the square,” he told eleven-year-old Naomi Landy of Perry Street, one of the “Children of Greenwich Village” who wrote an open letter to city newspapers pleading for playground improvements.

The trouble is that our plans were blocked by stupid and selfish people in the neighborhood who don’t want to give you a place to play, but insist on keeping Washington Square as it was years ago, with lawns and grass and the kind of landscaping which goes with big estates or small villages. These people want the square to be quiet and artistic, and they object to the noise of children playing and to other activities which we proposed.

Under these circumstances we moved our … men and material to other crowded parts of the city where playgrounds are badly needed and … people welcome them and don’t put obstacles in our way.

His comments had a ring of truth. The residents were effectively claiming ownership of a public space, and they did seem to oppose change of any kind. While Washington Square Park was on the back burner, Moses crafted a new approach. Once he had a plan, he rarely let it go. After the war he returned his focus to the area with the urban renewal plans for south of the park, holding secret meetings with top New York University officials for redevelopment under urban renewal. He also kept up the criticism of residents who sought to keep the neighborhood just the way it was, like an artillery commander softening up the invasion landing. Moses demonstrated both his annoyance at not getting his way and a rhetorical flair for beating down the opposition.

He wrote to a distinguished resident who called for historic preservation in 1950:

I realize that in the process of rebuilding south of Washington Square there would be cries of anguish from those who are honestly convinced that the Sistine Madonna was painted in the basement of one of the old buildings there not presently occupied by a cabaret or speakeasy, that Michelangelo’s David was fashioned in a garret in the same neighborhood, that Poe’s Raven, Don Marquis’ Archie the Cockroach, and Malory’s Morte D’Arthur were penned in barber shops, spaghetti works and shoeshine parlors in the purlieus of Greenwich Village, and that anyone who lays hands on these sacred landmarks will be executed if he has not already been struck down by a bolt from heaven.

Transforming Washington Square Park was an endurance test, and Moses was confident he would outlast the naysayers, as he had many times before. The urban renewal plans south of the park were moving ahead, and Moses promised the development teams that the new development would have a Fifth Avenue address. The developers, after all, were the ones who would make his urban renewal vision a reality.

His final chess move appeared on the front pages in 1952: the carriageway would be replaced with a north-south roadway of four lanes, two in each direction. The fountain would be eliminated. A roller rink would be installed on one side of the roadway and a new playground on the other. The model was Riverside Park, a long strip of green that ran along the Hudson on the West Side and was elegantly integrated with the off-ramps and free-flowing traffic lanes of the West Side Highway. Once and for all, traffic would be able to get through Washington Square Park. Fifth Avenue would be the address of the model new metropolis spawned by urban renewal, and resistance would be shown to be futile.

When Jane Jacobs had moved from the State Department to her new job at Architectural Forum in 1952, she had no particular plans to get involved in neighborhood politics. She was busy with her job, and with raising her two sons and, later, her infant daughter, Mary. But after she received the flyer from the Committee to Save Washington Square Park and wrote the mayor and the Manhattan borough president, she looked again at the letter for the name of the person organizing the opposition. It was a woman named Shirley Hayes, and Jacobs dashed off a note to her as well. “Thanks for your good work,” Jacobs wrote on the lower left side of a form to join the committee. “I’ve written the mayor and the borough president each, the attached letter. Please keep me informed of any other effective action that can be taken.”

Hayes, a mother of four who lived on East Eleventh Street, a short walk from Washington Square Park, welcomed Jacobs to the fight. Jacobs was impressed as she learned more about the woman who was so energetically organizing the neighborhood, typing up letters, recruiting volunteers, and scheduling evening meetings. Born in 1912 in Chicago and trained as a painter and an actress, Shirley Zak Hayes moved to New York to pursue her dream of making it on Broadway. A handsome blonde with a Marilyn Monroe hairstyle, Hayes met her husband, James, when both appeared in a production of Hamlet. They married, James took a job in advertising, and the couple chose to live in Greenwich Village and raise their four sons there. As a mother, Hayes grew to love the Village and Washington Square Park. She became increasingly upset at the big apartment buildings going up all over, and equally dismayed by Moses’s urban renewal project south of Washington Square. The park roadway plan, she was convinced, would destroy the neighborhood for good. “There is no justification for sacrificing this famous park and Greenwich Village’s residential neighborhood to either Mr. Moses’ commitments … or to this piecemeal and destructive approach to solving the city’s impossible traffic patterns,” she said. “A few women got together to say no, no, no.”

After the Moses proposal of 1952, Hayes founded the Washington Square Park Committee, a combination of three dozen community groups, church groups, and parent-teacher organizations from local schools. She befriended another concerned mother and neighborhood activist, Edith Lyons, and together they launched a grassroots effort to give a voice to a neighborhood they believed was under siege.

A prolific letter writer and an aggressive coalition builder, Hayes identified the most influential officials at City Hall and pressed them to listen to the views of the neighborhood. Her relentless pleas earned her a position on the Manhattan borough president’s Greenwich Village Community Planning Board, and in that position she demanded that the board come up with alternative plans for the park. At the same time, Hayes sought out as many residents, shopkeepers, and clergymen as she could find to join the effort. She wrote to her Greenwich Village neighbor Eleanor Roosevelt in 1953. She wrote to the Reverend Rosco Thornton Foust, rector of the Church of the Ascension, Sister Corona at St. Joseph’s, and the rabbi at the Village Temple, imploring them to mention park meetings in their sermons. She deployed neighbors to stand on corners and make traffic counts, so she had her own documentation of the number of vehicles passing through the neighborhood, instead of relying on the data compiled by Moses’s traffic engineers. She circulated petitions against the roadway plan and within a matter of weeks had four thousand signatures. She wrote dozens of letters to newspaper reporters. The correspondence piled high at the offices of the Manhattan borough president, occupied in 1952 by Robert Wagner, soon to be mayor. Moses, sensing that Hayes could lead an uprising, wrote to her personally in 1953, assuring her that her views were being considered.

From the day the Moses plan appeared in the newspapers, Hayes did not limit her fight to derailing the proposal. She was not interested in negotiating for a less harmful roadway. She sought no less than to block any roadway, and any car traffic whatsoever, through the park. There would be no deals and no compromise. Jacobs took note of this tactic as she waded into the Washington Square Park battle herself.

Her early involvement, following her letters to City Hall and the note to Hayes in 1955, was more as a foot soldier than a leader. The first time she was mentioned in a newspaper article it was inaccurately, as Mrs. James Jacobs. Jacobs helped drop off petitions at stores around her house and struck up conversations with shopkeepers and customers about goings-on in the neighborhood. Jacobs also went to local rallies and her first meetings of the Board of Estimate, the governing body that had the final say on any changes to Washington Square Park. She soon realized that to be effective, citizen activism required a more concerted effort—something akin to a full-time job. Merely following the twists and turns of the roadway battle was difficult, as seemingly definitive action at City Hall was followed by new Moses maneuvers that kept the plan alive.

The Greenwich Village residents had secured a victory in May 1952, when the Manhattan borough president, Robert Wagner, ordered the roadway plan withdrawn for further study. Then, in 1954, the City Planning Commission approved the next steps for urban renewal south of the park, making Moses more determined than ever to create a grand gateway through the park leading to the huge new campus of housing. In 1955, Moses made what he viewed as a major concession: submerging the four-lane roadway and building a pedestrian overpass across it. Depressing the roadway, he thought, might make it less objectionable, without building a full-blown tunnel, an idea promoted by Anthony Dapolito, a neighborhood baker who would later become known as the mayor of Greenwich Village. Boring beneath the surface was a common strategy for moving traffic through urban environments, and one that had already been used in New York near Grand Central Station. But it would be expensive to dig under the park and build a platform of public space above. A gentle dip and a pedestrian overpass were as far as Moses was willing to go.

The neighborhood lashed out against the submerged-roadway plan, calling it no better than the original four-lane proposal. By 1957, Hayes and Lyons were flooding City Hall with thousands of notes from residents in opposition to any new roadway and any car traffic through the park. Wagner’s successor as borough president, Hulan Jack, who initially teamed up with Moses to promote the submerged-roadway plan, backed off, and proposed a more diminutive, thirty-six-foot-wide, two-lane roadway.

Though Jack was a useful ally, he was clearly getting too soft with the residents, Moses thought. In a condescending letter that he began with the salutation “Dear Hulan,” Moses described the plan as “ridiculously narrow” and totally unworkable. He made it clear that no more compromises were to be made with the rabble-rousers. Four lanes, forty-eight feet wide, with a mall in the middle to be planted with trees, submerged if necessary but otherwise on the surface. No more modifications.

Determined not to let the neighborhood get the upper hand, Moses did his best to keep the residents off balance, delaying key hearings until the last minute, then quickly scheduling them in the hope of minimizing attendance. After twenty years of trying to redesign Washington Square Park, he had lost his patience, and he pushed harder than ever to deliver on his promise for a continuous Fifth Avenue. Shirley Hayes and Edith Lyons had marshaled an impressive effort, but the plan, thanks to Moses, was still under active consideration by the city. It would not die easily. Greenwich Village needed to step up its efforts to defeat it.

The turning point came in 1958, when Raymond S. Rubinow, an eccentric consultant who lived not on Washington Square but on Gramercy Park several blocks away, volunteered his services. Rubinow, a friend of Jacobs’s, had just started a career helping businesses like Sears and Welch’s grape juice create foundations to fund social and civic causes. An economist—his Russian-born father was credited with establishing the concept of social security—Rubinow had become obsessed with preserving New York City’s old neighborhoods and historic buildings, and devoted himself to such causes as saving Carnegie Hall from the wrecking ball. He took control of the organization that Hayes had built, and one of his first moves was to give Jacobs a greater role, as a strategist and additional liaison to the community and the media. After consulting with her, he changed the name of the community group to the Joint Emergency Committee to Close Washington Square to Traffic.

Growing up in Scranton, Pennsylvania, Jane Butzner became known for her sharp wit and her fearless challenging of teachers, both belied by the gentle mien on display in this early photograph. Courtesy of Jim Jacobs

Jane and Robert Jacobs camping at Montauk. Jane met Bob at a party in 1944; they would marry only weeks later. John J. Burns Library, Boston College

Urban pioneers Bob and Jane Jacobs, here assisted by first son Jim, renovated 555 Hudson Street in Greenwich Village, turning a dilapidated house into a cozy home. The house would become the unofficial headquarters for neighborhood activism in the fight against urban renewal and also provide the second-floor perch from which Jacobs made many of her most important observations on the functioning of city life. Courtesy of Jim Jacobs

By 1956, Jacobs was a staff member of Architectural Forum. That year she attended an urban design conference sponsored by the University of Pennsylvania, mingling with the leading theorists and designers of the day, including I. M. Pei (far right), Ian McHarg and Louis Kahn (third and sixth from left), and Chadbourne Gilpatric from the Rockefeller Foundation (talking to Jacobs). She was the only woman who wasn’t there as the wife of a participant. Grady Clay/courtesy of the Penn Institute for Urban Research/University of Pennsylvania

A Jew among bluebloods at Yale University just before World War I, Moses, seated at far left, worked his way onto the Senior Council and the Yale Courant, where he soon awed colleagues with his knowledge of literature and his intellectual prowess. MTA Bridges and Tunnels Special Archive

Moses held many positions but wielded the most power as chairman of the Triborough Bridge and Tunnel Authority, an independent organization with its own seal, its own fleet of vehicles, and hundreds of employees. Headquarters was by the bridge on Randall’s Island, isolated from other government offices in the middle of the East River. MTA Bridges and Tunnels Special Archive

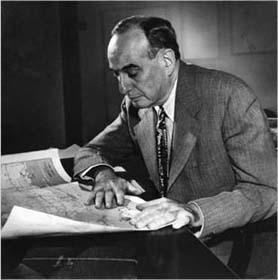

An early riser known for his prodigious work ethic, Moses early in his career mastered the art of drafting and then pushing through legislation designed to increase his power and financing. MTA Bridges and Tunnels Special Archive

Moses sought the extension of Fifth Avenue through Washington Square Park as the gateway to a signature redevelopment project, Washington Square Village. Moses pushed the towers-in-a-park layout, inspired by the modernist architect Le Corbusier, as the model for urban renewal and new housing construction in New York City, leading to the showdown over the proposed redevelopment of Jacobs’s very own neighborhood in Greenwich Village. MTA Bridges and Tunnels Special Archive

As she became a famous activist and writer, Jacobs continued to relish her family life. Here she is baking for her husband and sons at 555 Hudson Street. Courtesy of Jim Jacobs

Greenwich Village in the 1950s and 1960s was a haven for writers, poets, artists, and musicians, including Bob Dylan, and Jacobs, here at the White Horse Tavern, became part of the avant-garde, both as an author and critic of urban planning and in her citizen activism. Cervin Robinson

The elite promenaded there in the days of Henry James, then mothers with strollers, protest marchers, and folksingers in the beatnik era—Washington Square Park has served as an outdoor living room, respite, and gathering place. Here a young Ed Koch, future mayor of New York, strums a guitar near the fountain. Alvin Thayer/La Guardia and Wagner Archives/La Guardia Community College/CUNY

Jacobs encouraged her children to be front and center in neighborhood battles, as in this one against the roadway through Washington Square Park. Here her daughter, Mary, left, led a “ribbon-tying” ceremony in front of the parks arch in June 1958, celebrating an early victory in keeping traffic out of the cherished greensward. New York Daily Mirror/Courtesy of Jim Jacobs

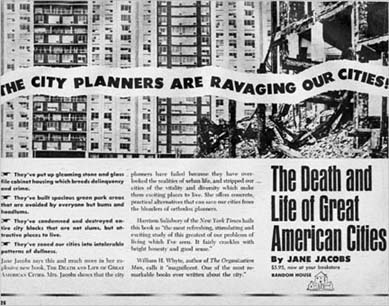

In 1961, Jacobs published The Death and Life of Great American Cities, an attack on the planning tactics embodied by Moses. The book, like Silent Spring and Unsafe at Any Speed, exposed the destructive outcomes of an established orthodoxy: in this case, modernist city-building. As the book exploded into the cultural discourse of the time, it dramatically altered the way that people viewed cities. Courtesy of Random House

Jacobs spent long days and nights at her typewriter composing Death and Life and gazed out the window at 555 Hudson Street for inspiration from the “sidewalk ballet” of her Greenwich Village neighborhood. Anthony Flint

Battling Moses, Jacobs befriended up-and-coming city politicians such as Ed Koch and Carol Greitzer (pictured here with Jacobs and Greitzer’s daughter Elizabeth). These politicians would play an important role in fighting Moses, city planners, and business interests keen on reaping the benefits of redevelopment. Courtesy of Carol Greitzer

Jacobs read about the proposal to bulldoze her neighborhood in the New York Times: fourteen blocks, including hers on Hudson Street, would be designated a slum and redeveloped, wiping out the city life Jacobs had just celebrated in Death and Life. New York Times

Trained as a journalist, Jacobs understood the need to court the press. She made herself available for interviews throughout her battles against Moses and New York City planning officials, and cultivated relationships with reporters from publications ranging from the New York Times to the Village Voice, a start-up alternative tabloid. John J. Burns Library, Boston College

In the fight against the plan to raze fourteen blocks in the West Village for urban renewal, Jacobs marshaled the residents and businesspeople of the neighborhood and employed children as spies surveying city officials and developers. The neighborhood held book and bake sales to raise money, including this penny sale at St. Luke’s Church. John J. Burns Library, Boston College

Moses sought expressways to run across New York, similar to his successful Cross Bronx Expressway, to relieve congestion and speed goods and services for the struggling New York economy He used models, such as this one of the proposed Mid-Manhattan Expressway, as well as glossy pamphlets, and he even produced a film to argue for these multimillion-dollar infrastructure projects. Black Star/MTA Bridges and Tunnels Special Archive

Moses proposed the ten-lane, elevated Lower Manhattan Expressway, which would have run down Broome Street, obliterating hundreds of homes and businesses and the cast-iron architecture of the area. He characterized the area as dilapidated and worthless and suggested that the superhighway would signal progress and bring economic revitalization. MTA Bridges and Tunnels Special Archive

Father Gerard La Mountain, pastor of the Church of the Most Holy Crucifix on Broome Street, turned to Jacobs for help as his flock, including immigrants and small businessmen, was set to be uprooted by the massive Lower Manhattan Expressway, counting on her to draw media attention and galvanize political support. Jack Manning/New York Times/Redux

Jacobs saw Greenwich Village and SoHo as under siege by highway and urban renewal planners, who condemned buildings with the “hex” sign of the X; her son Ned, on stilts, stands defiantly before one example. Designating neighborhoods as blighted slums to her was a self-fulfilling prophecy, hobbling efforts for grassroots revitalization. Ruth Orkin

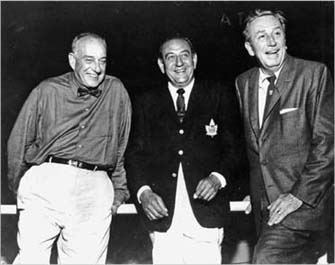

Moses had a flair for the theatrical and befriended Walt Disney (right, beside the musician Guy Lombardo), who shared a belief that sleek highways were the key element of modern life, and who contributed to exhibitions at the World’s Fair. MTA Bridges and Tunnels Special Archive

Jones Beach was an early triumph for Moses, and he was a frequent guest at the Jones Beach Theater, where Guy Lombardo appeared with showgirls from a performance of the musical Hit the Deck. The Jones Beach complex epitomized Moses’s vision of a great public country club. An avid swimmer, he regularly plunged into the ocean off the coast of Long Island for long solo workouts. MTA Bridges and Tunnels Special Archive

By 1967, Jacobs had grown more disenchanted with government and policy makers and joined a protest rally against the Vietnam War with her daughter, Mary, and husband, Bob. She would step up her radicalism in response to city planners and the proposed Lower Manhattan Expressway as well. Fred McDarrah/Getty Images

Jacobs with Susan Sontag and others in a New York jail, where they’d been taken after a Vietnam War protest. This was not the only time her activism landed her in jail. John J. Burns Library, Boston College

After the battle of the Lower Manhattan Expressway, Moses retreated from the spotlight, serving as a consultant and issuing memos to reporters, but spending more time at his Long Island home and bungalows on the beach; here he is shown with Mary, the secretary he married after his first wife died in 1966. MTA Bridges and Tunnels Special Archive

Worried that her sons would be drafted and discouraged by U.S. policies regarding cities, Jacobs settled in Toronto, battled a proposed freeway there, and eventually became a celebrated Canadian citizen. Maggie Steber

The cast-iron buildings of SoHo on Broome Street—the spot where the Lower Manhattan Expressway would have run—today are the sites of art galleries, designer boutiques, bistros, and the lofts of celebrities. Jonathan Stephens

Washington Square Park, with its signature arch and storied history dating to Henry James and beyond, is today one of New York City’s most celebrated public spaces—as difficult to imagine bisected by a highway as SoHo with a ten-lane elevated expressway, and the quaint Greenwich Village replaced by drab housing towers. Daniel Avila/New York City Department of Parks and Recreation

When Jacobs lived on Hudson Street in the 1960s, Greenwich Village was a bustling place. Today the neighborhood has become one of the most desirable—and pricey—areas in any city in the United States. Anthony Flint

“We weren’t trying to embrace all kinds of points of view about the Village, all kinds of political groups, all kinds of anything. We were trying to collect and concentrate on this issue, the people who felt as we did on that issue,” Jacobs recalled later. “In order to dramatize this and clarify this, a name like that was necessary—not something like ‘The Such-and-Such Association’ … that’s the reason Greenwich Village developed these strange and wonderful names, like ‘The Committee to Get the Clock Started on the Jefferson Market Courthouse.’ People knew what they were getting into. They weren’t getting into ideology. They were getting into a particular thing … [We joined] people who believed in a particular thing and might disagree enormously on other things.”

Though Hayes had attracted a wide range of activists to the cause, Rubinow and Jacobs sought to bring in even more firepower. They persuaded Eleanor Roosevelt to join the emergency committee, as well as the anthropologist Margaret Mead, who also lived in the Village. Jacobs asked her new friend the Fortune editor William “Holly” Whyte, author of the recently published book The Organization Man, to join, along with a respected local pastor, a prominent New York University law professor, and the publisher of the new alternative newspaper the Village Voice.

In the emergency committee’s early strategy sessions, Jacobs stressed the importance of breaking down the effort into specific and manageable tasks. She realized that Moses was in a stronger position; he had been implementing his vision for urban renewal citywide for several years and was backed by powerful developers who hoped to get rich while reversing the city’s economic decline. Construction of Washington Square Village, south of the park, was under way, and Moses would use this as a further argument for the highway. The developers there, he proclaimed, “were formally, officially, and reliably promised under the Slum Clearance Act a Fifth Avenue address, and access for the large new population in multiple dwellings replacing warehouses.”

Jacobs advocated changing the terms of the debate away from the broader picture that Moses was painting. The emergency committee’s best argument was that Washington Square was a park, and a park was no place for highways. Building on Hayes’s strategy of accepting no compromise, Jacobs took the position that whatever adjacent development was under way, the park should remain a park, and no vehicles should be allowed. There should be no negotiation, she argued, and no acceptance of a slightly less harmful roadway, like Hulan Jack’s proposal to reduce the number of lanes from four to two. If the roadway was built, and it connected to the Lower Manhattan Expressway, it would no doubt eventually be widened. Only killing the Washington Square roadway outright would put a stop to Moses’s grander plans.

It would take discipline, Jacobs said. The neighbors must resist the temptation to negotiate or compromise, to accept trade-offs and scraps of concessions. It would also take a stepped-up public-relations campaign, and for that Jacobs helped recruit Lewis Mumford, the architectural critic at the New Yorker, whom Jacobs had befriended after her speech criticizing modern planning techniques at Harvard.

Years earlier, Mumford had critiqued Moses’s plan for redesigning Washington Square as “absurd” and “a process of mere sausage grinding.” In 1958, he furnished a statement to the emergency committee that was turned into a press release. “The attack on Washington Square by the Park Department is a piece of unqualified vandalism,” Mumford said. “The real reason for putting through this callow traffic plan has been admitted by Mr. Moses himself: it is to give the commercial benefit of the name ‘Fifth Avenue’ to the group of property owners who are rehabilitating the area south of Washington Square, largely at public expense. The cause itself is unworthy and the method used by Mr. Moses is extravagant. To satisfy a group of realtors and investors, he is as ready to change the character of Fifth Avenue as he is to further deface and degrade Washington Square.” He went on to condemn Moses’s “insolent contempt” for common sense and good civic judgment. “Washington Square … has a claim to our historic respect: a respect that Mr. Moses seems chronically unable to accord any human handiwork except his own. [It] was originally used as a potter’s field for paupers; it might now prove to be a good place to bury Mr. Moses’ poverty-stricken and moribund ideas on city planning.”

Mumford’s suggestion that the Washington Square roadway was primarily to serve real estate developers had resonance. The foundation of urban renewal was to bring in the private sector—and in the case of the project south of Washington Square, a nonprofit, New York University, as well—to revitalize cities. Moses got no direct financial benefit from his relationship with the developers, but Mumford put him on the defensive by adding to the contention that the whole project was an insider deal. Moses hit back with a press release of his own.

“The public was told that this area was not substandard, that we were ruthlessly evicting small business firms which could not go elsewhere, that we were illegally substituting high-rental for low-rental residence, that our project was a ‘steal,’ ‘giveaway’ [and the] ‘sacrifice of perfectly good buildings,’” Moses said. “The critics failed to understand that Title I [the urban renewal program] aimed solely at the elimination of the slums and substandard areas. It did not prescribe the pattern of redevelopment, leaving this to local initiative.”

Without private developers and New York University, the old warehouses would continue to be a fire hazard, Moses argued. “Who will clear out the rest of this junk?”

But Mumford’s challenge prompted others who argued that urban renewal was no justification for destroying the park with a roadway. Within days, other prominent New Yorkers weighed in. Eleanor Roosevelt, an early skeptic of Moses’s plans, devoted her “My Day” column in the New York Post to the controversy: “I consider it would be far better to close the square to traffic and make people drive around it… than to accept the reasons given by Robert Moses … to ruin the atmosphere of the square.” Norman Vincent Peale, pastor of the Marble Collegiate Church, argued that “little parks and squares, especially those possessing a holdover of the flavor and charm of the past, are good for the nerves, and perhaps for the soul. Let us give sober thought to the preservation of Washington Square Park as an island of quietness in this hectic city.”

And then there was Charles Abrams, a Columbia University professor and Greenwich Village resident who bore some resemblance to Moses, in terms of both his strong intellect and his patrician upbringing. Nothing less than the power of the people to maintain healthy city neighborhoods was at stake, Abrams argued. “Rebellion is brewing in America,” he said at a crowded neighborhood meeting in July 1958. “The American city is the battleground for the preservation of [economic and cultural] diversity, and Greenwich Village should be its Bunker Hill … In the battle of Washington Square, even Moses is yielding, and when Moses yields, God must be near at hand.” Abrams turned the speech into an essay for the Village Voice titled “Washington Square and the Revolt of the Urbs.”

The high-profile support was encouraging. This was beginning to look like a fight that could be won. But Jacobs knew not to be overconfident. Employing her journalistic skills, she learned as much as she could about Moses, to better understand her foe. He seemed to control every function of city government from his lair on Randall’s Island. He had years of practice battling neighborhoods and opponents, from Long Island to Spuyten Duyvil. To prevail, the neighbors would need a sophisticated strategy. In the evening strategy sessions of the emergency committee, Jacobs assumed the role of a war-room impresario in a modern-day political campaign and urged a three-pronged effort: continued grassroots organizing designed to draw in more allies, more pressure on local politicians, and a stepped-up campaign to gain attention in the media.

Greenwich Village in the late 1950s was fertile ground for bringing politicians into the cause—those in danger of being voted out, and newcomers trying to break in. Jacobs surveyed the political landscape with this in mind. A number of Greenwich Village residents were plunging into politics hoping to give the neighborhoods more of a voice at City Hall, and to change a government that did not seem to be listening. An ambitious young woman, Carol Greitzer, had befriended Jacobs and parlayed community frustrations into a job as a city councillor. “We were doing our own planning, and that really hadn’t ever been done before,” Greitzer said. “It was an exciting time.”

Edward Koch, who later served as mayor of New York, began his career as well in those days, as a member of the Village Independent Democrats—an organization founded during Adlai Stevenson’s 1956 presidential campaign to bolster liberal and progressive causes, and to support candidates against leaders still in power from the Tammany Hall political machine. Koch sought to shift politics away from patronage and political favors to true representation of ordinary citizens. Jacobs saw that men like Koch were seeking to make a name for themselves, beholden to no one in power, and eager to join a neighborhood cause that could give them publicity.

The politicians already in power required different treatment. Hulan Jack, the Manhattan borough president, seemed to be hearing the voices of opposition in the neighborhood, but was still clinging to the idea of some kind of new roadway through the park. A new champion was needed. One night as Jacobs drifted off to sleep, her husband woke her with the idea to tie closing the park to traffic to the upcoming election. The state assemblyman Bill Passannante was in a tight race against a Republican challenger, who opposed the roadway through the park. Passannante, Bob Jacobs said, could be encouraged to go a step further, by calling for stanchions at the park’s perimeter blocking everything but bus and emergency vehicles. If he agreed, he would get the support of the emergency committee’s sizable voting bloc; if he didn’t, those votes would go to his opponent. Passannante very quickly became the first elected official to back the idea of closing off the park to car traffic. Jacobs also encouraged the neighborhood activists to appeal to a handsome young Republican running for Congress: John V. Lindsay, whose Democratic opponent quickly joined him in opposing the park roadway plan.

Jacobs and the other committee leaders continued to meet privately with the politicians, persuading them that the roadway battle was a central issue among voters. But Jacobs became even more convinced that one tool was more important than anything else to keep the public pressure turned up high on the Board of Estimate, the City Planning Commission, the mayor’s office, and all the officials either elected or running for office: the media. A journalist herself, Jane Jacobs knew a few things about getting attention.

The 1950s was a time of change for newspapers in New York City. The number of newspapers had decreased from earlier in the century, but there was still the New York Times, the Herald Tribune, the World-Telegram and Sun, the Journal American, the Daily News, and the New York Post, and competition for stories was fierce. Jacobs knew that reporters feared getting scooped, and would be less likely to ignore a well-timed press release—especially one issued over the weekend, traditionally slow news days—if the neighborhood group could establish itself as credible and newsworthy. Using competition as leverage was the only way to counter the reporters’ dependence on officialdom for information, a dependence that made them wary of printing critical comments about planners and commissioners. Nowhere was this more true than with Moses, who continued to have friends in high places at the biggest media outlets and froze out writers who strayed.

Not content with publicity in newspapers like the New York Times, which covered the battle thoroughly but always quoted Moses at length, Jacobs sought out different venues that would give greater voice to the neighborhood’s sense of outrage. For this there was the Village Voice, which had been established in 1955 by Dan Wolf, Ed Fancher, and the novelist Norman Mailer as an alternative city newspaper that emphasized arts and culture—but also took on local and political issues with more of an edge and an opinion. The Voice dedicated itself to hard-charging reporting and criticism, ultimately winning three Pulitzer prizes, but it also covered neighborhood issues, paying special attention to the point of view of ordinary citizens.

The Voice journalist and Greenwich Village resident Mary Perot Nichols covered every hearing and rally on Washington Square Park—and later urban renewal in the West Village and the Lower Manhattan Expressway as well. Jacobs and Nichols became close friends over the course of the Washington Square Park battle, and Jacobs made sure the budding journalist had access to inside information. A good relationship with someone in the newspaper business was critical, Jacobs knew. Nichols’s news stories and a Voice editorial made for a stirring defense of both community activism and the value of public space. “It is our view that any serious tampering with Washington Square Park will mark the beginning of the end of Greenwich Village as a community. Greenwich Village will become another characterless place,” Wolf wrote on the editorial page. “Washington Square Park is a symbol of unity in diversity. Within a block of the arch are luxury apartments, cold-water flats, nineteenth-century mansions, a university, and a nest of small businesses. It brings together Villagers of enormously varied tastes and backgrounds. At best, it helps people appreciate the wonderful complexity of New York. At worst, it reminds them of the distance they have to cover in their relations with other people.” When a Moses aide grumbled that the “awful bunch of artists” in Greenwich Village were a nuisance and couldn’t agree to get anything done, Wolf proudly proclaimed that he hoped “there are thousands of nuisances like that within a stone’s throw of this office.”

While the Voice dedicated its pages to the fight, other media had to be drawn in. What the newspapers needed were good pictures, and Jacobs launched what would become a signature tactic: putting children front and center. They were the ones who used the playgrounds and ran around the park, after all. Jacobs deployed kids—dozens of “little elves,” as she called them—to put up posters and ask for signatures on petitions. Young people, she soon realized, were irresistible to newspaper photographers; they were the perfect photo opportunity. There was precedent for a child becoming a symbol in a park battle. In 1956, residents near Central Park battled Moses over his plan to expand a parking lot for Tavern on the Green at Sixty-seventh Street. Mothers rolled strollers to the site and defiantly blocked the parks commissioner’s bulldozers, and the image of a “little soldier”—a toddler refusing to cede her ground for construction work—became an enduring icon. Moses ultimately backed down, and Jacobs recognized a winning tactic when she saw one.

“She would bring the three children to the square on weekends to collect petitions demanding that the highway plan be canceled and the park permanently closed to traffic,” recalled Ned Jacobs, Jane’s son, who was seven years old in the spring of 1958. “This was during the beatnik era, and my brother and I were outfitted with little sandwich boards that proclaimed ‘Save the Square!’ That always got a laugh because people knew that ‘squares’ would never be an endangered species—even in the Village. These were also the dying days of McCarthyism. People were afraid—even in the Village—to sign petitions for fear they’d get on some list that would cost them their careers. But I would go up to them and ask, ‘Will you help save our park?’ Their hearts would melt, and they would sign. Years later, Jane recalled that we children always collected the most signatures.”

Getting officials and the media to see battles through the eyes of children would continue throughout Jacobs’s career. One day when she was shopping for long underwear at Macy’s for her sons, Ned and Jim, the clerk asked whether it was for hunting or for fishing. “It’s for picketing,” she replied.

The tactics began to work. On June 25, 1958, responding to the residents’ opposition, the city agreed to close Washington Square Park to traffic on a temporary basis while the roadway matter was put to further study. The next day, the New York Daily Mirror published a photograph of Mary Jacobs, three and a half, and Bonnie Redlich, four, holding up a ribbon that had been symbolically tied as a “reverse ribbon cutting.” The caption read: “Fit to Be Tied.”

The success of the neighborhood’s media campaign did not go unnoticed by Moses. His riposte was to suggest that perhaps the emergency committee should be allowed to win—and be responsible when the area was hopelessly knotted by traffic jams. “There is something to be said … for letting unreasonable opposition have its way; find out by experience that it doesn’t work. How can you choke off all traffic in Washington Square? It is preposterous.”

The City Planning Commission continued to deliberate on what to do with the park while the vehicles were temporarily blocked and in July 1958 voted in favor of Hulan Jacks narrower road. Moses stepped up the rhetoric, vowing that his scheme would ultimately triumph “when drummed-up local hysteria subsides, mudslinging ends and common sense and goodwill prevail.”

But by the fall of that year, with local campaigns in full swing, the emergency committee made a critical move: appealing to Carmine De Sapio, New York’s secretary of state, Democratic leader, and de facto head of the Tammany machine. He was exactly the kind of old-school pol that Rubinow, Koch, and Greitzer and the rest of the Village Independent Democrats were determined to drive out of New York City government. But he was also a Greenwich Village resident. If he could be convinced to stand up against the roadway plan, it would have real influence. The New York University law professor on the emergency committee, Norman Redlich, was chosen as the envoy, and found a receptive audience in the Democratic party boss. De Sapio let it be known that the Board of Estimate should schedule a hearing, and that he planned to furnish some rare public testimony. Before he addressed the board, he was presented with a scroll listing some thirty thousand people who had signed in opposition to the roadway plan. Dozens of residents appeared outside City Hall wearing green “Save the Square” buttons and twirling parasols with “Parks Are for People” printed on them; among the crowd were Jane Jacobs, Shirley Hayes, and Eleanor Roosevelt.

Wearing his trademark dark glasses, which reflected the flashes of newspaper cameras, De Sapio asserted that Greenwich Village, as well as Washington Square Park, represented “one of the city’s most priceless possessions and as such it belongs to every one of our 8,000,000 fellow New Yorkers … To change the character of this beloved central symbol of the Village would be, ultimately, to eradicate the essential character of this unique community.”

Having worked with the influential De Sapio over the years, Moses knew that he had been checkmated. A month after the hearing, Hulan Jack, taking his cue from De Sapio, gave up on his two-lane roadway plan. The Board of Estimate directed the traffic commissioner to close the park to all but buses and emergency vehicles.

After so many fits and starts, this was the end of Moses’s roadway plan—no Fifth Avenue address for his housing towers south of the park, no free flow of traffic. That fall, Moses addressed the Board of Estimate, in a desperate move for reconsideration. It was galling, the way he had let this get away from him. “There is nobody against this,” he said. “Nobody, nobody, nobody but a bunch of, a bunch of mothers.” Jacobs watched, both amazed and satisfied, as he turned and walked to a waiting car.

The party to celebrate the victory took place on Saturday, November 1, 1958, at the base of the Washington Square arch. The carnival atmosphere brewed in the late morning with placards, children, “Square Warriors,” balloons, and throngs of people. The event had an official name—the “grand closing” of the park to traffic. The members of the emergency committee set up a ribbon tying—as opposed to a ribbon cutting—as the big photo opportunity for the press. De Sapio, Hulan Jack, Bill Passannante, and Ray Rubinow all proudly held the green strip of fabric and smiled for the cameras. Jacobs stayed in the background.

Pink parasols bearing the slogan “Parks Are for People” and green buttons that proclaimed “Save the Square” were out again in force. Jacobs watched as reporters scribbled notes and photographers snapped away. Speakers read messages of congratulations that had been sent from New York’s governor, Averell Harriman, Mayor Wagner, and Lewis Mumford. “I will do my utmost to see that this road is never opened again,” said Passannante. “Look up the avenue. Any traffic jam? Any cars begging to come through the park? I see only people.”

Just after noon, Stanley Tankel, a resident of West Eleventh Street, drove a battered old minibus festooned with a banner that read “Last Car Through the Park” under the arch and out toward Fifth Avenue.

About seven months later, the neighbors held another celebration, a masquerade ball attended by a thousand people, with more politicians and newspaper publishers and local artists. At midnight, someone held a lighter to a life-size cardboard car that had been assembled by a theater group, and the vehicle burned to mark the triumph over Robert Moses. Jacobs and all of Greenwich Village, it seemed, partied into the night.

The celebrations may have been premature, as the ban on car traffic was still intended to be temporary; the city considered it an experiment. But the weeks and months following the closing went better than anyone in the neighborhood could have hoped. As Passannante had observed on the day of the ribbon tying, the knotted traffic that Moses predicted never materialized. Because the New York City street grid in the area was so extensive, drivers had lots of options. The network absorbed the traffic flow. The experiment at Washington Square Park would become a principle of modern-day traffic engineering—that speeds are seemingly slower as drivers make their way through a traditional street grid, but they often get to destinations faster compared with a crowded, single express route. Some rethink the need to traverse the area by car, and find alternative transportation, like mass transit.

Moses did not accept defeat gracefully. In 1959, he refused to agree to close the park to vehicular traffic unless all the streets around the park were widened to eighty feet and all the corners of the greensward rounded off so, as Moses argued, traffic could navigate through the area better. But he had lost his influence on the matter of the park, and the city was in no mood to continue the battle with new proposals. The buses from the Fifth Avenue Coach Company continued to make their turnaround just past the arch.

Within two years, the buses would also be gone. Jacobs, by that time, had returned to her writing and played a less active role in this stage of the fight. But Shirley Hayes and Ed Koch, representing the increasingly powerful Village Independent Democrats, continued to press for the elimination of all motorized vehicles in Washington Square Park. A new parks commissioner, Newbold Morris, submitted to the pressure and urged the head of the transit authority to reroute the bus turnaround. With Mayor Wagner’s blessing, Washington Square Park was permanently sealed off from all traffic, including buses, a few weeks before the assassination of John F. Kennedy in November 1963. One and a half acres of park were reclaimed, once the paved roadway areas were no longer necessary. This time, Koch and Hayes symbolically escorted a last bus out of the park.

The victory for the bunch of mothers was complete. Moses had been trying to fix Washington Square Park since 1935, and a quarter century later he was forced to give up. The achievement was infectious as neighborhoods across the city found a new voice in development, public works projects, and especially parks. Central Park became an important battleground. A year after the ribbon-tying ceremony at the Washington Square arch, Joseph Papp, head of the New York Shakespeare Festival, took on Moses over permitting for free performances there. New Yorkers assumed a new sense of ownership over public space.