Henry wobbled to a stop. He leant his bike against a telegraph pole near Cassie’s crimson dragster, down by the wharf. ‘Hello there,’ he said, unclicking his helmet.

‘Hello, yourself!’ said Cassie, peering up. She turned back quickly and swirled her bare feet in the water.

‘I’ve been looking for you.’

A silver tinny buzzed past, out towards the breakwater. A lacy wake of water danced towards them. ‘You disappeared so fast.’ Henry sat down beside her. The water sloshed giddily against the edges of the stone wall. ‘Where’d you go?’

‘I had some stuff to do,’ said Cassie, shrugging. ‘The laundry and some shopping. And so . . .’ She rubbed her knees. She lunged forward to fling a scrap of seaweed from her foot.

The water was green as glass.

Henry watched a large shadowy fish flit just above the reeds, a smaller school of fish drifting behind like a tiny speech bubble. He glanced over his shoulder. A lady in grey overalls and black gumboots was hosing down the deck of a fishing boat, tied up tight to the wharf. Everything ponged of fish.

Cassie sank her chin onto her hand. She stared hard into the water as if she was thinking about something extra tricky. She sat silently, her shoulders slumped, like someone had given her bad news.

Henry checked the palms of his hands secretly, just in case they were beginning to sweat. He rubbed them stealthily on the back of his shirt. Holy Macaroley, he hoped he wasn’t about to suddenly turn into gibbering, nervous idiot like Patch! Maybe it was something a person could catch, like measles or chickenpox?

‘Your bike . . .’ said Cassie, in a small voice.

Henry froze. Dismay burst in the middle of his chest. It blazed out through his whole body like a fiery meteor shower. ‘Oh,’ he whispered.

‘Before on the bike path,’ said Cassie, ‘when everyone was clapping and cheering . . .’ She stopped.

Henry stared at his knees. It felt like the night roaring of the ocean was in his ears.

‘It looked like . . . I don’t know—’

Henry clenched his hands, till the tops of his knuckles shone.

‘That you’d only just . . . learnt how to ride or something.’

Henry wiped his lips. ‘Yes,’ he murmured. His mouth was so dry.

‘So. Then I got to . . . thinking about . . . your brakes.’ Cassie cleared her throat. ‘Were they ever—’

Henry shook his head. ‘No.’

‘Oh . . .’ said Cassie, glancing over.

‘They never were.’ Misery oozed in Henry’s stomach like a slick of oil.

Cassie turned and stared out towards the breakwater. ‘So . . . it was just a big . . . lie?’ She stared out towards the breakwater.

A swirl of fish scales glittered on the cement beside Henry’s leg. He brushed them into a small pearly pile. ‘I got the bike for Christmas. It’s brand—’

‘How come you didn’t just say—’

‘New.’ Henry tugged at the neckband of his T-shirt. ‘I don’t know.’ Something was panging away in his chest. ‘I didn’t want you to think I was—’

‘I wouldn’t have cared.’

‘Some kind of baby,’ finished Henry.

Two pelicans flew overhead, their wide wings whooping, their tummies sagging. Henry wondered how come they just didn’t drop out of the sky. He took a deep breath and gazed down at his shin, at the fresh graze from the morning.

‘I like it when things are true.’ Cassie snatched up a pebble and curled her fingers around it tightly. ‘I don’t like it when people pretend. When they say one thing and mean another. I don’t like it how my mum says she is only going to sing one more time on a cruise ship and then she’s going to come home forever. I don’t like it how she tells me my dad loves me, when I’ve never even met him and he never even sends me a birthday card. I don’t like it how she tells me we’ll have a tin-roofed house by the sea one day, all of our own, when I know I’m going to live in a meerkat caravan always. I hate it how people make up stupid, dumb old stories to make themselves feel better, instead of telling things straight-up and true.’

A gust of wind blew across the water, wrinkling it like a skin. Cassie flung her arm back and tossed the pebble out as far as she could. It made a satisfying plop right near an old catamaran.

Henry watched the little circles ripple out bigger and bigger. Where would they go, those ripples? All the way to the other side of the world? Till they touched the toes of another girl, dangling her feet in the water from a stone wharf, filling her up with a longing for something big and true?

Oh, blimey, he had let that dumb old story about his bike brakes slip out, almost by accident. But then he let it stay out. He pretended he could ride, even when he couldn’t. He didn’t realise how telling a tiny, stupid story to make himself feel better could possibly make someone feel worse. But now he knew. He could see it. Cassie cut off and adrift, sucked away by a fast current, more left out and lonely than before.

Oh, gosh, there was something weighty, sharp-cornered and icy-cold fierce smarting right in the middle of his chest. There was a word in his mouth, hot as a star.

‘Sorry,’ he whispered.

Cassie glanced at him. Their eyes met and held.

‘I’m sorry I wasn’t . . . straight-up and true.’

Cassie’s mouth quivered and she turned away quickly towards the wharf, as if something very fascinating was happening there, like the world’s biggest fish had just been caught.

Henry ducked his head. He watched the breeze sweep this way and that way, until it winked out, just like that. A bunch of little kids squealed on the big nest swing across the water. His throat ached and he suddenly felt so tired, like he hadn’t slept in a hundred years.

‘It’s okay, you know,’ Cassie murmured. She brushed a hand across her cheek. ‘I mean . . . it’s just . . . I understand . . . and it’s a very big bike.’ She glanced over her shoulder and stared at it, glinting silver in the sun. ‘Probably, if you think about it . . . everyone in the whole world would be worried about riding that thing for the very first time.’

Henry felt a sharp twinge of relief. ‘Everyone in the whole world?’ he breathed.

‘Yes,’ said Cassie.

‘Even Donald Bradman?’ He could feel a kind of gladness humming right through him.

‘Especially the Don!’ said Cassie. ‘Imagine if he’d fallen off a bike like that and broken his arm. He might never have ever played for Australia!’

‘Ha!’ said Henry.

‘The whole history of cricket would never be the same!’ said Cassie. ‘So there!’

Henry bent the toe of his sneaker back. ‘That would have been one terrible Worst Case Scenario,’ he said, with a lopsided grin.

‘I know,’ said Cassie, smiling.

They watched a long line of cyclists, small as ants, meander up the hill to the lookout.

Cassie nodded. ‘Have you been for a ride out there yet?’

‘I just came back.’

‘Where’d you go?’

‘All the way to the lookout and then down to Nugget Rock.’

‘Did you see any seals?’

‘Nope! Not a single one.’

Cassie dipped her fingers into the water. She splashed her face gently. ‘Did you like it?’ she asked, rubbing the bottom of her T-shirt across her cheeks.

‘I raced my dad,’ said Henry, ‘down the tiniest hill and he gave the biggest, scariest screech I’ve ever heard, because I think he was worried about what my mum would do to him if I fell off and got maimed.’

‘Maimed,’ said Cassie. ‘Your dad. He’s so—’

Henry nodded. ‘I know.’

‘Funny.’ Cassie sighed. She stretched her T-shirt out.

A seagull bobbed on the water, floating up close to their feet, like it was eavesdropping. Henry itched his nose against his shoulder. It was true. His dad was funny. It was like he was always expecting some good thing to happen, just around the corner.

‘You know, when Patch was little he thought all seagulls were called sea girls!’ said Henry. ‘And every time we eat fish and chips now, Dad always says, Hey, Patch, here come all your sea girls!’

‘Sea girls,’ said Cassie, laughing.

Henry wanted to ask Cassie a question. It was roosting in his head like a bird. But he wasn’t sure. Maybe some questions weren’t right to ask, especially if they were snoopy and nosy and made someone’s heart sorer than before. But then again, what if he didn’t ask? What if no one asked anything important, just slunk back into their shells like shy snails? Would that leave people sometimes feeling lonelier than ever before?

‘Is it true?’ he asked slowly. ‘About your dad . . . that you’ve never ever . . . and the . . . birthday card and everything?’

Cassie rested her chin on her knee. ‘Well, you know, my dad . . . he left before I was born. He’s a musician. He used to play banjo in the city, beneath the statue of Queen Victoria. That’s where my mum met him. She said it was love at first sight and he had a voice like an angel. I’d like to hear him sing. I would. But my Pop reckons he’s a no-hoper.’

‘A what?’ asked Henry.

‘A no-hoper.’

‘What does that mean?’

‘I’m not sure.’

Henry wrinkled his nose. ‘Is it a person without any hopes?’

‘Maybe,’ said Cassie. ‘But I think my Pop meant it in a different way. Like my dad is a not a person to hope in.’

The sun baked down and seared so loud, Henry’s eyes hurt. He thought about his exuberant, buoyant, happy Dad and his big, wild, brimming love and how good a butter-into-hot-bread hug felt and how strange and unthinkable it seemed that a person couldn’t hope in their own dad.

‘Where is he now?’ asked Henry.

‘No one knows.’ Cassie flicked a small stone into the water. ‘Maybe he’s singing in Rome, in front of a fountain, with all the pigeons pecking about his feet. Or maybe he’s singing love songs on a bridge in Paris, for all the couples about to propose. Or maybe he’s not singing at all anymore. Maybe’s he’s given up on all that and he’s married to someone new and he goes to work every day and does a yucky, boring job and the best part is when he comes home, all tired out from working with numbers, to a little girl and a little boy who run to the front door when they hear the garden gate open with a big squeak.’

Henry shook his head. ‘Oh, wow!’

‘I don’t mind,’ said Cassie, shrugging. ‘Because my Pop is very good to me, you know. Even if he’s a bit grumpy now. My Nan used to say my Pop likes to pretend he’s a peanut brittle chocolate, so no one will ever know he’s really a big old strawberry cream.’

A family rode by on their bikes, shouting and laughing and ringing their bells, racing each other down the path.

‘Do you reckon—’ Henry stopped.

‘What?’

‘I’m wondering,’ said Henry, glancing at the family, ‘if you’d want to—’

‘Go for a ride?’ Cassie scrambled to kneel up. ‘YES. Oh, yes. I would!’

‘Excellento,’ said Henry. ‘But where shall we go?’

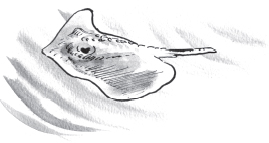

Cassie clutched suddenly at Henry’s elbow. ‘Look! Out there! It’s Heathcliff.’

‘What?’ asked Henry. ‘Where?’

‘See the ripple,’ said Cassie. ‘Near the wharf!’

Henry made binoculars out of his hands.

‘He’s gone for a cruise around the edge of the dock but he’ll be here in a minute,’ said Cassie. She pulled out a little plastic bag from the pocket of her backpack. ‘The charter boats came back early because it was so rough out at the island. Everyone was gutting fish and there were so many birds and so many stingrays, so much snatching and grabbing. You know, sometimes the birds steal a scrap right out of another bird’s beak and poo in the water with happiness at exactly the same time.’

‘Holy Wamoley!’ said Henry, dropping his hands.

‘I know,’ said Cassie. ‘It’s so gross. Just wham bam squirt – big white cloud.’

‘Oh, geez!’ said Henry.

‘Now take Heathcliff. He has very good manners. Mostly he prefers a pat to a feed. So sometimes he misses out on eating. So I like to hang around to give him a little bit extra. Here he comes!’

‘Holy Guacamole!’ cried Henry, as the stingray swam towards them. He shuffled backwards. ‘He’s almost as big as a coffee table.’

Cassie grinned. ‘My Pop reckons he’s like a gigantic fishy pool cleaner.’

‘He’s much bigger than I expected,’ said Henry, shivering. He tucked his legs up tight.

‘I know,’ said Cassie, opening up the plastic bag and scooping out another sliver of squid. She dropped it into the water. ‘But remember, he’s not dangerous and he’s very friendly.’

The sun went behind a long tuft of cloud.

‘He looks a lot like the Millennium Falcon.’

‘The what?’

‘You know, like Han Solo’s ship in Star Wars.’

‘Oh, yeah,’ said Cassie. She dropped another scrap of squid in and then ducked down and rolled over onto her stomach. Her eyes followed Heathcliff as he swooped past.

‘It must be hard,’ said Henry. ‘Without his whole tail.’

‘I know. It’s not good. He doesn’t have any protection now because he doesn’t have a barb. Sometimes I worry about that at night.’ Cassie splashed her hands in the water. Heathcliff drifted back towards them and she bent right down and stroked her hand along his skin. ‘Do you want me to tell you something?’ Henry could see a tiny scar on her cheek, like a small crescent moon.

‘Sure,’ he said.

‘I tell Heathcliff everything!’

A small spark of sadness flared in Henry. ‘What sort of things?’

Heathcliff nudged Cassie’s hand. She laughed and reached out again to pat him. ‘Oh, well . . . all sorts of stuff. Sometimes I talk to him about my Pop and the arthritis in his fingers that aches so bad in the winter that his fingers curl over and how it makes him crankier than a cut snake. And sometimes I talk to Heathcliff about my mum and the things I remember from when I was little. Like the marshmallow smell of her hair and the sound of her singing me to sleep. And sometimes I make wishes.’

‘What sort of wishes?’

‘Sometimes I wish for my mum’s cruise ship to stay afloat and not get hit by bad storms. And sometimes I wish my Nan would send a big shooting star, so I know she’s still thinking of me, even in heaven. And sometimes I wish my Pop would tell jokes like he used to, even the bad old ones he’s told a million times before and sometimes I wish people never went away. I wish that the most. I wish people stayed forever and there was no more missing anywhere. No more pinching just here.’ She pressed a hand against her chest.

Henry nodded. He watched Heathcliff swirl towards them again. ‘You know what I wish?’ he said.

‘No.’

Heathcliff whirled past and Henry gazed at his missing tail. ‘I wish every sad thing would come untrue.’

‘Ah, yes,’ said Cassie. ‘Me too! I wish that too.’

Heathcliff wheeled by again like a superhero with a rippling black cape.

‘You can pat him,’ said Cassie softly. ‘If you want.’

Henry swallowed. He could. He could reach out with his hand and touch Heathcliff, just one tiny little stroke with the tips of his fingers. But then again, Heathcliff wasn’t a cat or a dog or a guinea pig or a budgie. He wasn’t tame like that. He was still a wild creature, even without most of his tail.

There was a fluttering feeling in Henry’s chest, a tiny buzzing frenzy. He inched closer to the edge. It was normal to be nervous. He had to remember that. He hunched over and gazed into the water.

‘Heathcliff’s making a circuit,’ said Cassie. ‘He’ll come round again in a sec. Get ready!’ She dug into her plastic bag and dropped in another piece of squid. ‘Won’t be long now!’

Henry rubbed the palms of his hands against his shorts. The bravest people were the ones who were scared and did brave things anyway. They were more brave than the people who did daring things without a second thought. It looped in Henry’s head like a catchy chorus from a song.

‘It’s okay,’ said Cassie. She was grinning at him. Her eyes were trophy gold and gleaming. And he knew it didn’t matter that his legs were shaky and his tummy was gurgling loudly. It didn’t matter if he got it right or wrong.

‘Here he comes!’ Heathcliff flew like a bird above the reeds, rising higher and higher, swift as a shadow.

Henry wriggled forward on his knees and then lunged out, dipping his hand into the water. With one long flap of his wings, Heathcliff swooped by, his blunt snout breaking the surface. And Henry stretched out and stroked his speckled back, the skin sandpapery as a kitten’s tongue. ‘Holy Raymoley!’ he whispered.

Heathcliff rolled and spun and flapped. He ducked and dived and circled back, rising up, alive and playful, funny as a puppy and yet the fiercest and wildest animal Henry had ever touched.

The sun burst out. The whole sea blazed with spangles of light. Henry gazed down, bedazzled and silent, his fingertips tingling.

‘I did it,’ he breathed.

‘You did!’ cried Cassie.

Heathcliff turned and coasted away with one creamy flutter of his wings, out towards the catamaran.

‘Hey!’ called Henry. ‘Come back!’

‘He will,’ said Cassie. ‘Don’t worry. He likes you. He’s not playful like that with everyone.’

Henry clutched his dripping hand to his chest. It came to him that he hadn’t fallen off the stone ledge and landed on top of Heathcliff and been carried out into the deep and slipped off and ended up being swallowed by a whale shark! It dawned on him that his Worst Case Scenario had not happened at all. He started to chuckle.

‘What?’ asked Cassie, smiling.

‘I don’t know,’ said Henry. It was impossible for him to put it into words. How he could sense some kind of fierce, trembling wildness rise up in him too. Some determination not to let the worry about the terrible things that might happen stop him from enjoying the grand, genius good things right before him.

‘Here he comes again!’ said Cassie.

Henry dunked both hands in the water. When Heathcliff swirled past and rose up, he and Cassie patted him together.

Then Henry closed his eyes and made some big wishes about calm seas and shooting stars and bad old jokes, hoping Heathcliff might carry them out to sea, through the shallow patches of turquoise and teal, through the shimmering splashes of kingfisher blue, through the pools of sapphire and indigo, right out into the listening deep.