Aspie Mentors’ Advice on Improving Empathetic Attunement

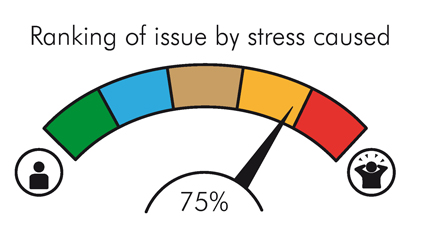

Stress Ranking: 16*

*Please see “The 17 Stressors” at the end of this eBook to put this research in context.

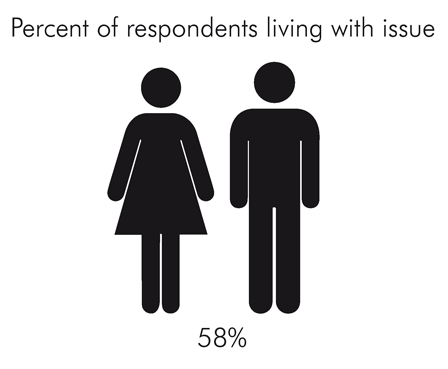

Some people with Asperger’s/HFA are unable to feel empathy (an “emotional understanding”) for others. Examples of this would be: not sensing if friends or family are uncomfortable or suffering; reading or hearing a news story about people involved in a tragedy or disaster and not being able to sense their discomfort; and witnessing a life-changing event such as the death of a family member and not having a change in feelings. Do you have concerns about empathetic attunement?

Dr. Patrick Suglia

Because of our straightforward nature, we Aspies tend to be accused of not having “feelings.” People might think we are uncaring and cold and that we only think about our own needs. I learned to be more empathetic toward other people’s emotions by monitoring and remembering my own at certain points in times. Then, I turned the tables, so to speak. When I felt pain from a specific illness or injury, such as when I had kidney stones, fear when I had my stroke, and sadness when my marriage ended and whenever a family member passed away, it is true that I didn’t show a great display of emotions. But that didn’t mean I didn’t have them. I felt them internally and in my own way. Then I took such situations and I thought to myself, “What would another person be feeling in this same situation?” But it didn’t end there. I then had to respond to the other person’s concerns.

Our silence during emotional times may seem like an advantage to some, believe it or not. It shows that we are calm and that we have it together during stressful times. Because of this, we are often the ones who can continue on with what needs to be taken care of without feeling overly burdened. But for the people who are close to us, this is not what they want to see. They want to know that we care about the situation and that we identify with what they may be going through. For me, this was possible not only by identifying with my own experiences and placing another person in the picture, as I explained, but then taking the next step of responding with words of acknowledgement. One thing I came to learn as a caregiver is that the greatest thing people want and need from others is simply a word of acceptance of the fact that they are being affected, and that you support them in their plight. You don’t have to cry with them or be in pain, too. You just have to say, “I understand, and I support you.” This means so very much to a hurting neurotypical.

The genuineness of your words comes from the recognition that you once felt that pain, too. If your words are not true, the neurotypical will sense it. While you may not show much emotion at the time you are hurting, neurotypicals can be quite dramatic in their emotional expression. It is because we are wired differently that we do not exhibit such displays? Neurotypicals (NTs) need to understand that that doesn’t mean we do not have the capacity to experience pain or recognize it in others. Being able to more openly show our experience of pain, and acknowledge it in others, are learned behaviors for us.

Usually we don’t even know if somebody is being affected by a situation if they aren’t telling us verbally or shouting out. If they do tell us, or shout, then it is obvious. Sometimes, people will become unusually still or quiet if something negative is affecting them. If you know the person and you observe this difference in them, that would be a good time to ask them, “Is everything okay?” We probably wouldn’t normally be able to tell. But we can make it a rule of good social conduct to be observant for such a change. By doing so, we will certainly be rewarded in the end for understanding when something is wrong, and acknowledging that. This will lead to people opening up to us more, trusting us more, and thanking us for being so caring.

Debbie Denenburg

I am not empathetic—not according to the specific definition of the word. I do not take on the actual feelings or emotions of any other person. That said, I would clarify that, although I do not have this attribute, I do have a nature of compassion. I am affected by feelings. I can sense things like hurt, frustration, anger and sadness. I care about those things. I have had enough pain in my life that I hate seeing anyone else experience it. I have been accused of being callous. I have, at times, said nothing and done nothing. That didn’t mean that I was oblivious to what was happening. It doesn’t mean that I didn’t respect the seriousness of the moment. I have learned that there are expectations in times of turmoil.

When someone is seeking empathy, I explain that I probably don’t know what he or she is feeling, but I do care. If you find yourself in that position, try the following behavior: become their rock. That is someone who can be leaned upon for strength. Don’t pass judgment on a person whose feelings have become out of control. Allow them to speak freely. That includes letting them get hysterical or angry. Listen without interrupting. Don’t challenge anything they say. Be the person who allows them to vent, in a safe place, all that internal, volatile buildup. If they just want to be quiet, let them know it’s okay.

When others are in a vulnerable position, they need someone who is strong to be on their side—someone who shows by example that it’s possible to get through tough circumstances and still find peace. Be that person.

Richard Maguire

I do not hold the opinion that people with Asperger’s are unable to feel empathy for others. I believe that we may have difficulty making the links and accessing what is there.

One thing that troubled me when I was accepting my autism was the image of us being cold, aloof, tetchy and unfeeling. I could not reconcile this with my ability to care, nor with that of the autistic people I knew and worked with. We are often the first people to know something is wrong with someone and often the last to know what to do about it.

I have learned to deal with this and have helped many autistic people deal with this over 30 years of work. What I have done is helped people learn about their emotions, name them, learn what they feel like (emotions are felt physically), where they are located, what they are and how to reference and name them. I have worked on the understanding that there is a lot of disconnection between the person, their emotions, consciousness of and ability to describe emotions and what to do about them. Most people, including me, have been scared and sought distance and distraction. Once these connections are made, I have helped people move on to an understanding that they are present in other people, emotional connections can be made and things can be done with reference to emotions.

This has been a revelation to me and others I know. It opens the way to being able to tune in to emotions and feeling in ourselves and other people. Thus, a whole new landscape of life, feeling and connection can be accessed. I always say that people have a latent empathic ability; I will strenuously deny they have no capacity for empathy. I think a lack of empathy best describes psychopaths, not autistic people. I believe empathetic attunement needs to be taught, unlocked and developed in many people. I also believe this to be true for non-autistic people, who may be more adept at covering up their lack of empathy with better social and communication skills.

Many autistic people work in social care, medicine, nursing and psychology, as these careers give structures to contact, show empathy, understand and care for people. This does not fit the computer geek, recluse or engineer stereotypes, but it is common in autism.

I believe every autistic person has as much love, joy, empathy and life in their heart as anyone else; what we often lack is the ability to make the connections and get this part of our life engaged and working.

Also important in this is getting our anxiety levels as low as possible. Someone carrying a burden of excess anxiety will find connecting with people hard, and showing empathy even harder. I know many people who are often the first to tune in to someone else’s emotional state but are the last to know what to do about it. This is usually read as having no empathy and is often taught as such. I believe this does us a disservice and can cause people to overlook the possibility that a lot of us can make the connections and be overtly empathetic.

I believe we often need coaching from someone who knows the emotional and empathetic process to help us build up gestalts and routines for being able to tune in and then show empathy.

Larry Moody

Are you shy, tongue-tied or brain-locked?

As a teen, I always thought I was shy…almost terminally shy. There were times when I wanted to talk to girls but I couldn’t. I just couldn’t seem to be able to get the words out. I knew what I wanted to say but I couldn’t, I just couldn’t… That pretty well defined shy in my mind at the time. Little did I know that something very different was taking place.

As fathers go, I got lucky and have a good one. On the other hand, I was far from being the perfect son. Particularly problematical were my attention deficit disorder (ADD) and memory deficits, which were not diagnosed until much later in my life. I loved to build things to play with, and that involved using his tools while he was at work. All too often, I would leave one or another of his tools out wherever I had used it. In Florida where I grew up, leaving a tool outside almost always resulted in rust…a sure giveaway, even if I later remembered to put it back where it belonged. Punishing lectures were the norm. Sometimes I could not answer quickly enough when questioned after a thorough tongue-lashing, or could not answer at all. A sure sign of defiance…or so he thought. Little did either of us know that something very different was taking place.

About four years ago (circa 2009) I was one of two panel presenters speaking about autism at an evening meeting of parents and teachers at a school in Burnsville, MN. Having been asked a question about relationships, I was trying to relate something to do with my ex-wife and me, something that was very emotionally laden and I locked up mid-sentence… I could not speak! Nothing but gibberish came out before I went silent. I closed my eyes, went inside and self-calmed for a few seconds. I opened my eyes and continued, but nothing came out except more gibberish. Again I went inside. When I came back after a few more seconds I was able to finish the statement I was trying to make. I then changed the subject and told the group that I felt I needed to explain what had just happened with me.

I call it brain-locked. Someone else might call it a severe form of being tongue-tied. It makes no difference what you call it; it’s still an uncomfortable feeling. With me, it only happens when my emotions are highly charged, and not often even then. My brain is racing. I know precisely what I want to say, but my tongue will not cooperate. No matter how many times I repeat it in my mind, when I try to speak, it either doesn’t come out at all, or it comes out as gibberish… “Gaa, uh, ugh…oeirt erqg ajkeg…” You get the point. It’s as though the connection between my brain and my tongue is lost for a while. My brain simply disconnects. For most of my life I would fight this inside myself. And the more I fought to speak, the worse it would get. Eventually, I developed for myself the technique of closing my eyes, going silent inside to self-calm for a few seconds, and then returning. Usually I can then continue with what I was saying. If I can’t continue, I simply repeat the process until I can.

Well, after my explanation, the program continued for about 20 more minutes and ended. As the parents and teachers were filing out of the rows of seats and heading for the door at the back of the room, one woman turned directly toward me instead. I have a significant deficit when it comes to appropriately interpreting facial expressions. So when I saw tears running down her cheeks, I knew something was amiss, but I did not know what I had done. Do I stand, or do I run? Well I stood there… From bravado, or more likely a deer in headlights, I’m not sure which. She walked right up to me and wrapped her arms around me in a hug as I stood there silently, and she said: “Thank you, thank you…” And she proceeded to tell me her story:

She has a six-year-old autistic son. Earlier, when I went into what I later explained as brain-lock, she instantly recognized that that is what happens with her son occasionally. She said she had always thought he was being defiant and evasive, refusing to answer her, and she had punished him for it many times…but will never again! She thanked me once again, turned and left. I never knew her name.

To have that kind of positive impact on the lives of even one parent and child makes all my efforts and occasional embarrassing goofs as a speaker worthwhile. That’s why I speak out. That’s why I do this and other things to help improve understanding and acceptance of us by the neurotypical population.

Paul Isaacs

I believe understanding others is the key to getting on in life with relationships, friendships and even with workmates. It’s an important attribute that can affect people around you. I think that the myth that autistic people lack empathy is not correct. I have met many giving people all the across the Autism Spectrum from non-verbal to verbal…all of whom have wisdom and empathy.

My parents, who are both on the Autism Spectrum, are also very empathic souls who give a lot of time to others such as friends and family. I likewise do the same. I like to help other people in times of need and stress. To be a good friend, you must be there for others and treat others how you would like to be treated in certain situations. It builds trust, stability, emotional connectivity and binds you and the other person.

My parents were always helping with broadening out the awareness of others. I lived in a sensory-based world and was non-verbal for a long time. I had love for my parents and people I like—I just didn’t show it a typical way. But as I got older, I developed ways of showing my love and support for my friends and family. There is no “wrong” or “right” way of showing pure empathy; it is a about building bridges of understanding between both parties to gain a mutual understanding.

Here are some tips and advice I have learned from parents:

•Shake hands when greeting friends and family members for the first time (depending on preference, sensory issues and situation).

•Ask that person how they are (this concept of questions will build up over time as you get to know them).

•Be aware that other people have thoughts, feelings, beliefs and ways of life that are different from yours.

•When you are having difficulties, talk about them to friends and family members.

•When your friends and family are having difficulties, be there for them.

•Think of others’ feelings, not just your own.

Ruth Elaine Joyner Hane

Lack of empathy is common in today’s fast-paced culture. Our daily media sources flash grotesque images of murder, war, disasters, accidents and violence so often we become desensitized. Whatever feelings of empathy we may have become lost in daily exposure.

The nurse who checked my blood pressure during a post-surgery visit to my doctor asked, as she charted my numbers, “How are you doing?” “Not well, I have a lot of pain and I can’t tolerate the pain medications the doctor prescribed.” She answered with her back to me, “Yes, that surgery is painful, that’s what they all say.” I knew that recovery would be difficult, but had expected more empathy from the nurse. I felt as if she was indifferent.

Even though the nurse’s response was factually correct, and she was taking care to enter my weight and blood pressure accurately, she was ignoring empathy. With increasingly heavy patient loads, medical professionals are challenged to take time to use caring touch and kind words that convey an understanding of pain in recovery from major surgery.

We lose our humanity if we as a culture fail to develop an understanding of another’s suffering. I recently saw media coverage of a man who slid onto a river that had partially frozen over, leaving an open patch of water where his sled landed. Instead of immediately calling emergency services and expressing concern by assuring the stranded man that help was on the way, the onlookers stood at the edge of the ice and laughed hysterically. This was a life-threatening situation. Fortunately, one woman realized this in time to secure a rope to a branch and rescue the man.

One of the ways I have learned to develop empathy is by observing people who have a generous supply. These people notice others in need and naturally offer assistance and words of assurance, and are good listeners. I believe the nurse who was too busy, in the example I gave, was at a loss to understand how to respond to my problem with pain medications. If she had paused in her charting, turned to look at me and simply expressed empathy by saying, “I’m sorry,” I probably would have felt better.

Empathy is taught very early in life, from the kind care given when we are infants. When I was born, I could not tolerate touch, being held or scratchy, rough clothing and blankets. The message my body sent was pain, as if I had burns all over. A neighbor, who was good with babies, discovered that I relaxed in very warm water baths. She securely held my body beneath the water with just my face exposed while she cooed a singsong nursery rhyme. She used empathy and compassion to help me reduce my tactile anxiety.

Most people learn empathy, sympathy, compassion and understanding incrementally, but it does not come naturally for a person who lacks the ability to take another’s perspective. Next time something happens, and you are unsure how to respond, ask yourself these questions:

•How would I feel if this happened to me?

•What would I like to hear or have done for me that would make the situation better?

•Would this person like the same thing as I would, or some other remedy?

•Is doing something the best option or could words of sympathy be better? Or both?

If you freeze in indecision and there is someone present who has skills for showing empathy, pay attention to what they do and say. You will have more skills for understanding when an opportunity for empathy arises again.

Mitch Christian

There’s a kind of instant subconscious reaction to the emotional states of other people that I’ve understood better in myself over the years. If someone approaches me for a conversation and they’re full of worry, fear, anger or joy I find myself suddenly in the same state of emotion. That’s probably why I have such an intense dislike for people with negative attitudes. Sometimes I react without knowing it to the other person’s emotional state, for instance, if they’re upset for some reason, then I sense it and I may feel guilty for no apparent reason, or if they’re exuding anger, I might feel anxious and want to get away from them.

On the other hand, I don’t often respond to someone else’s situation just from hearing the words that describe it. So, if I’m listening to a news program that’s discussing a tragedy, I won’t feel anything at first, until they reveal personal details about the people affected. At that point, I can start to feel overwhelmed and need to stop listening. To me, it makes sense that I would only genuinely feel for someone else if I know something about him or her as a person.

My stronger emotional reactions are often delayed. It took about two months before I cried after my grandmother died. While I was watching a movie I found myself sobbing when an elderly lady died, and I realized that it was actually my grandmother I was thinking about. A few years later, when my mother died, I had a similar reaction but it happened sooner and without warning. It was the next day, early in the morning, when the feelings rose within me, and for a couple of minutes I cried more intensely than I ever had. A few minutes later it happened again, only not as strongly.

Sometimes it’s overwhelming to have too much bad news in my personal life and I will block out part of it. While my mother was dying of cancer, I heard that someone I knew had major heart surgery due to severe blockage of the arteries. It must have been too much for me to handle, and apparently I blocked the news from my mind, because months later I heard about it again, and realized that I had forgotten to ask anyone about how he was doing.

At other times, I will express what looks like an inappropriate response, especially to a stressful event. While I was at work one time, a co-worker started choking on some candy. I had an urge to laugh and looked at him with a big grin. Someone else had called for help, and by that time the candy had dislodged from his throat. He was upset with me, so I made up a story and told him that I thought he was just kidding around. I think it was the stress of the situation that made me react the way I did.

Thinking back over these situations makes me realize that my emotional responses, or lack of a response, will often seem out of place to many people. From my point of view, my reactions are actually stronger than normal, but to others they don’t occur when expected or in the manner that is expected. It helps to be aware of these differences in order to develop a sense of self-acceptance and to understand that other people will not realize that I am an empathic person, just in a different way. In some situations, it may help to explain that to the other people involved.

Anita Lesko

I am always the first one to pick up on something amiss with another individual. I am able to distinguish very subtle facial cues that others would not see, or it might be a feeling I pick up from them. In any case, I’m aware there’s something different. The only problem is, I don’t know what to do about it! I get extremely uncomfortable and my first and only reaction is to avoid it.

Recently, a co-worker’s son was killed in an accident. I felt absolutely horrible for her. For a parent to lose a child is devastating. She was out for a while. Upon her return everyone was going to her to hug and console her. I felt so very uncomfortable and awkward that I just avoided her, and didn’t go anywhere near her for months. When I did have to talk to her, I would totally avoid the topic. I realize this is a terrible cop out. I feel very badly inside, but it’s the best I can do. I have no clue how to make my face and voice seem like I mean it. If I said something in my monotone voice, it wouldn’t sound right. And my inability to make appropriate facial expressions would come across as inappropriate. Avoidance thus becomes my best coping mechanism.

The only good news is that I can recognize another person’s feelings and have compassion for them. In fact, I think I feel more compassion than most NTs. So many people are totally wrapped up in their own lives, and barely notice things around them. However, I notice everything going on around me, especially the news. I admit that I am a news junkie. With that comes exposure to daily tragedies happening around the world, all of which sends me on the emotional rollercoaster of life. I am often troubled for days after hearing something sad on the news. Yet if I mention it to others, they blow it off. This is my gauge of my compassion for others.

Another thing I can now do is recognize that I have upset others. This generally doesn’t occur until after the fact. I didn’t realize that I was going to make them mad or upset before I said or did something. Once I’ve done that, I can then see their reaction to it. Then I can look at the whole picture and see why I made them upset. The best I can do is say I’m sorry, and use the experience as a learning tool. Next time I might be able to draw from it and approach things differently, all being well, with a better outcome!

Since learning of Asperger’s, my perspective has greatly changed. It has enabled me to see how the choices I make affect others. I am still a work in progress. I still make others upset or angry—I hope I’m doing it less and less. I don’t intend to hurt others, and I certainly don’t like it to happen to me. Because it’s not natural to me to recognize these things, I really have to work at it, which is what makes it so easy to mess up. I aim to look at things from the other person’s perspective. Once you start training yourself to do that, it gets easier to figure out what you did wrong. I’ll never get perfect at this or anywhere close, but I’m on the right track. That’s what is important. I do recognize what others are feeling, and I feel for them. I’ll just keep trying to get better at showing them how I feel.