Is Mike Matheny a Catching Genius?

KEITH WOOLNER

On December 13, 2004, the San Francisco Giants signed catcher Mike Matheny to a three-year, $9 million contract. What made this signing so remarkable was that the Giants already had a good catcher on their roster in A. J. Pierzynski. Pierzynski was younger, a better hitter in 2004, and a better hitter over his career. In fact, Pierzynski’s worst seasons in batting average, on-base percentage, and slugging average were as good as Matheny’s best. Pierzynski already had a year of experience working with the Giants’ pitchers. He was arbitration-eligible, meaning the Giants could have ensured his return for at least a season by offering him salary arbitration. Since a player rarely gets full market value through salary arbitration, the Giants could have secured their 2005 catcher at a better price than if they had ventured into the free-agent market.

Yet the Giants signed Matheny anyway because there were other considerations besides money, or even hitting. As Mike Bauman put it on MLB.com, Pierzynski “was not, to put it mildly, a particular favorite of the pitching staff.” Putting it less mildly, the Giants had a rebellion on their hands.

The pitchers were convinced that they could not work with Pierzynski behind the plate. Now, the Giants staff was not exactly Tom Seaver, Juan Marichal, and Bob Gibson, and no catcher in the world would have made them so. But the team did the expedient thing and chose to believe them. The Giants’ decision to swap Pierzynski for Matheny starkly illustrates the belief that catchers make an immense defensive contribution. Though personality issues played a role, the team essentially chose Matheny’s defense over Pierzynski’s offense.

A catcher can influence a pitcher’s performance in at least ten ways:

1. He can study the opposing batters and call for the right pitches in the right sequence.

2. He can use his glove and body to frame incoming pitches to subtly influence the umpire to call more strikes.

3. He can be attuned to what a pitcher wants to throw, or what pitches he is throwing well, and keep his pitcher comfortable.

4. He can control the tempo of the game, calling pitches quickly when a pitcher is in a groove or slowing things down by heading out to the mound for a quick meeting.

5. He can monitor a pitcher’s emotional state and use leadership and psychological skills to help a pitcher maintain his focus.

6. He can be skilled at blocking balls in the dirt so that the pitcher is not afraid to throw a low pitch with runners on base.

7. He can watch for signs of fatigue and work with the manager to decide to make a pitching change before the game gets out of hand.

8. He can engage in conversation or actions to distract the batter while staying within the rules of the game. A distracted batter is less likely to get a hit.

9. He can remain aware of the game situation and call for an unexpected pitch for the situation, gaining the element of surprise.

10. He can prevent opposing baserunners from stealing, either by throwing them out or keeping them from trying to steal at all.

This last item is the most obvious and therefore most celebrated aspect of the catcher’s job. A major factor in a catcher’s defensive reputation is how he controls base-stealing. Ivan Rodriguez would be legendary for his ability to throw runners out from his knees even if he called the worst game in the business. However, catchers have another major responsibility besides controlling the running game, and that is working with pitchers. The first nine items on the list all have to do with the catcher’s handling of the pitcher. It is here that the subtler, more powerful influences of a veteran catcher are said to appear.

Ultimately, these influences should show up as pitchers’ being more effective. They should give up fewer hits, walks, and runs when working with a good “game caller” and more if paired with a poor one. One of the first attempts to prove this theory statistically came in the book by Craig Wright and Tom House, The Diamond Appraised. Wright looked at a catcher’s ERA (CERA)—that is, the ERA allowed by pitchers when that catcher was in the game—and compared catchers on the same team to determine whether each one was good or bad at handling pitchers. He was careful to take into account the fact that some pitchers have personal catchers, and thus some catchers get to work with better pitchers more often.

Wright concluded that there were significant differences in catcher game-calling ability, and that those differences were reflected in their CERAs. Good defensive catchers posted significantly better CERAs than their teammates. Wright cited six-time Gold Glove winner Jim Sundberg as being overrated defensively because his CERA was regularly worse than any other Rangers catcher. Gino Petralli was singled out as one of the worst catchers by CERA, largely because of his mechanical flaws in receiving pitches. The best catcher by CERA, according to Wright, was Doug “Eyechart” Gwosdz, who posted spectacular CERAs backing up Terry Kennedy with the Padres in the early 1980s. Catcher ERA became a fairly well-accepted, if esoteric, statistic by which to measure catcher game-calling.

But Wright’s findings were flawed. The results cited were based on limited, anecdotal evidence. Wright had not presented a comprehensive analysis that showed that CERA had any predictive value or measured any intrinsic skill of a catcher. In fact, the differences among catchers appear to be random and don’t appear to correlate with any actual defensive ability. In Baseball Prospectus 1999, a study looked at every qualifying pitcher-catcher battery over a seventeen-year span and compared how the pitcher did with the given catcher, versus all other catchers on the team. Diving even deeper than just analyzing runs given up, the study looked at every plate appearance, examining the specific number of hits, walks, and extra-base hits given up. This is akin to looking at a pitcher’s batting average, on-base percentage, and slugging average allowed and seeing if they varied according to who was catching at the time.

They did vary, but randomly. There was no trend of catchers who performed well in one year performing well again the next year. Contrast this with what we see with batters hitting home runs, or pitchers getting strikeouts. Good home-run hitters like Adam Dunn or Albert Pujols generally remain good from year to year. That didn’t happen with the catchers’ opposing batter statistics. Catchers who posted excellent game-calling results one year were just as likely to be at the bottom of the pile the following year as the worst catchers. It’s akin to saying that Johan Santana and Kirk Rueter were each equally likely to lead the league in strikeouts. This lack of consistency, and the fact that the results for all catchers closely matched what we’d expect if the game-calling was perfectly random in effect, suggested there is no such thing as game-calling skill, or at the very least that it was eluding detection.

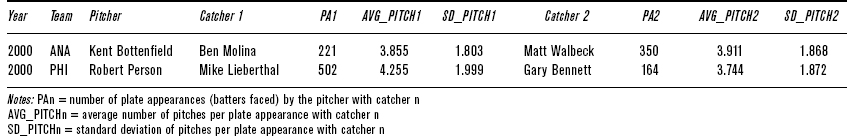

TABLE 3-3.1 Examples of Pitcher-Catcher Combinations, 2000

Several follow-up studies were done, both at Baseball Prospectus and elsewhere, in an effort to find proof that some catchers have a portable pitcher-handling skill—that some, by their mere presence, improve a pitching staff. No statistical evidence for a significant pitcher-handling or game-calling ability—such as would reduce the number of runs the opposition puts on the scoreboard—has been found.

But what about other possible effects? Do some catchers improve their pitcher’s efficiency, helping him get through more batters with the same number of pitches, or get more borderline strike calls, thus giving the pitcher the advantage of favorable counts? In the Baseball Prospectus database, we identified 3,361 instances where a pitcher worked with two different catchers for at least 100 plate appearances on the same team in the same season. Table 3-3.1 shows some examples.

Our analysis showed that catchers did not show any consistent ability to influence average pitches per batter. In looking for year-to-year trends, we found that there was at best the faintest relationship between catcher performance in consecutive years. When Mike Lieberthal worked with Robert Person, for example, Person averaged more than half a pitch more per batter than when he was throwing to Gary Bennett, as shown in Table 3-3.1. But the very next year, their positions were reversed, with Person throwing 0.15 more pitches per batter with Bennett catching than with Lieberthal.

One surprise was that the range of results within a season was much wider than would be expected by chance. If you look at enough pairs of catchers, you’d expect some big differences through random luck alone. But there were more pairs of catchers with big differences than the math tells us there should be. Is this an indication of some true ability? Or are there other factors at work? We will come back to this question later in the chapter.

There are some other places we can look for a catcher’s defensive ability. A catcher who frames pitches well should get more borderline calls. A higher percentage of pitches that are taken should be called strikes for a good framing catcher. Once again, nothing indicating any “framing” ability shows up.

Another way a catcher might help a pitcher is with his location within the strike zone. If pitches are spotted better, batters should have a harder time putting them into play. Can a catcher help a pitcher make batters swing and miss? Yet again, nothing in the statistical record supports the idea of this being an actual catcher ability. We did, once again, observe an unusually large range of performances between pairs of catchers. Though there was no year-to-year consistency, there were more extreme differences between some catchers than would be expected if everything was left to chance.

One of the simplifying assumptions we made in our analyses is that the mix of batters seen by each catcher is more or less the same. But this is not necessarily so. Because pitchers, particularly starting pitchers, play in relatively few games compared to everyday players, the mix of opposing teams that they face is more variable. A pitcher may get 30 starts; one catcher may have caught 10 of the starts and the other 20. The starting lineups in each of those 10 starts will probably get three to five plate appearances in each game. The opposing batters in those 10 games are thus overrepresented in that catcher’s sample. If a handful of those opponents are free-swinging teams, it will artificially drive up the differences between catchers, not because the catchers themselves are skillfully making them miss but by the luck of the draw and the repetitive nature of how plate appearances are distributed in a game.

This factor affects all of the studies that rely on comparing two catchers working with one pitcher. The small number of games any starting pitcher appears in, compounded by dividing that number across two catchers and then facing the same nine opposing batters for most of the game, creates more variability in batter characteristics than our simple model of more or less league-average opposing batters can accommodate.

We’ve considered four possible ways that good game-calling catchers might distinguish themselves from poor ones in the statistical record. For each of them, we’ll check how Mike Matheny, whose defensive exploits formed the basis for this chapter, measures up. There are three instances where a pitcher worked with Matheny and another catcher for at least 100 batters in two consecutive years. In 1996–1997, Matheny and Jesse Levis caught both Mike Fetters and Scott Karl. In 2000 and 2001, Matheny and Eli Marrero both worked with Andy Benes.

1. Good game-callers would help pitchers allow fewer hits, walks, and extra-base hits, and thus fewer runs than poor ones. This does not seem to be the case. A. J. Pierzynski might not have been his pitchers’ best friend, but neither should he shoulder the blame for less-than-stellar pitching. As for Matheny, his battery-mate Mike Fetters was better at preventing runs with Jesse Levis in 1996 but better with Matheny in 1997. Scott Karl posted better performances with Matheny in 1997 but virtually identical performances with Matheny and Levis the year before. Andy Benes pitched slightly better with Matheny than with Eli Marrero catching him in 2000 but substantially better with Matheny behind the dish in 2001.

2. Catchers who read their pitchers well might help pitchers be more efficient, lowering the average number of pitches needed per batter. The research showed a wider-than-expected variation between catchers but no consistent effect from year to year, and the wider variation can be explained by imperfect assumptions about the characteristics of opposing batters. Matheny was better than Levis when working with Karl in both 1996 and 1997. He merely equaled Levis’s performance when working with Fetters in 1996 and fared worse than Levis in 1997. When Benes pitched to both Matheny and Marrero in 2000 and 2001, he fared better with Marrero than with Matheny.

3. Catchers who frame pitches well might get more strike calls from the umpire by framing borderline pitches. Again, we see no evidence that certain catchers produce more called strikes than others. Matheny was worse than Marrero in called strike percentage in both 2000 and 2001 with Benes. He was better than Levis in 1996–1997 with Karl but worse than Levis with Fetters in the same two years.

4. Some catchers might help with a pitcher’s location, inducing more missed or fouled pitches when the batter swings. Though the variation between catcher pairs was larger than expected, no discernible year-to-year trend distinguished itself for catchers. Matheny and Levis were comparable working with Fetters in 1996. Matheny was better in 1997, but Levis posted better numbers than Matheny in both years when working with Karl. Matheny was better than Marrero with Benes in 2000, but Marrero was better in 2001.

One of the most controversial results from the sabermetric community is the lack of evidence supporting big differences in catcher defensive ability, other than differences in controlling the running games. Professionals within the game insist that catchers make a gigantic difference and that the question is simply beyond the capability of statistics to find. However, the further we look into catcher performance, the fewer places the elusive realm of catcher influence has to hide. There is no objective evidence that the catchers considered to be the best at their craft actually improve pitcher efficiency, increase strike rates, induce more misses and fouls, or do anything else to reduce batters’ offensive output. If the professionals are right and the best game-callers are having some effect that statistics can’t measure, we still have to ask how much offensive production a team could responsibly give up to obtain such an undetectable improvement.

Quotations on Catcher Duties Through the Years

Brawn and Brain, A. J. Bushong, catcher, Brooklyn Baseball Club, compiled by Arthur F. Aldridge (John B. Alden Publishers, 1889).

“No position to my mind is so high or so powerful as that of catcher.”

“It is a good point or an advantage, for the pitcher is thus relieved somewhat of a share of the responsibility if a ball that is asked for is hit. He consoles himself with the thought that it wasn’t all his fault, and so can perhaps do his work better.”

“Each then understands the other in a variety of ways, knows his weak and strong points, and in the end must work together successfully.”

Baseball, the Fans’ Game, Mickey Cochrane (New York: Funk and Wagnalls, 1939).

“One of the major requirements of a catcher is to install confidence in the pitchers he is receiving. They must have absolute faith in his judgment and his ability to catch every pitch” (p. 40).

“Pitchers are funny persons and must be cajoled, badgered, and conned along like babies, big bad wolves, or little sisters with injured feelings.”

“A catcher who asks a pitcher if he needs help must have some doubts. . . . He gets to know the speeds of a pitcher’s stuff better than the pitcher himself.”

Baseball: How to Become a Player, John Montgomery Ward (Cleveland, OH: SABR, 1993; reprint of The Athletic Publishing Company, 1888).

“There are some cases in which a steady intelligent catcher is of more worth to a team than even the pitcher, because such a man will make pitchers of almost any kind of material.”

Baseball: Individual Play and Team Strategy, John W. (Jack) Coombs, baseball coach, Duke University (New York: Prentice-Hall, 1945).

“I consider it very important for the catcher to warm up the pitcher who has been selected for the game. . . . So doing gives the catcher an opportunity to judge properly the speed, the curve, and the control which the pitcher has on any kind of ball that he might pitch.”

New Thinking Fan’s Guide to Baseball, rev. ed., Leonard Koppett (Toronto: SportClassic Books, 2004).

“Then there is the matter of ‘handling the pitcher.’ This has nothing to do with fielding skill, but with psychology, rapport, intelligent calling of pitches, pacing, even personality. It’s important, but it’s largely subjective.”

“Joe Garagiola . . . stresses the inanity of some pseudo-expert reactions. Talk that a catcher ‘called a great game’ is just as silly as blaming ‘a bad call’ for the home run that was hit. The pitcher is doing the throwing and the responsibility is his. Great pitchers make brilliant catchers, and poor pitchers make dumb ones.”