Do Players Perform Better in Contract Years?

DAYN PERRY

It’s a familiar refrain among fans and mainstream sportswriters: Players perform better in their “walk years,” the seasons that precede entry into the free-agent market. Players are aware, the theory goes, that a big walk year will increase their value on the open market and thus fatten their wallets. Free-agent contracts now run as high as nine figures, and major league ballplayers know they have a limited career window. It makes sense that they’ll employ a little extra focus and time—in the batting cages, on the mound, or in the gym—during that walk season. Their performance that year could mean the difference between a set-for-life contract and one that simply tables the same pressures for a few years. Players have every self-interested economic reason under the sun to be at their best when free agency looms.

Take the conspicuous example of Adrian Beltre. In 1994, the Los Angeles Dodgers, pursuing one of the most hotly coveted talents ever to come out of the Dominican Republic, signed Beltre to what they believed was an allowable contract. A few years later, Beltre’s agent Scott Boras discovered that his client had been signed at the age of sixteen—too young according to the rules of Major League Baseball. As a result, Boras agitated to have Beltre declared a free agent. Eventually, MLB Commissioner Bud Selig ruled that Beltre would remain Dodgers property but that the organization had to suspend its scouting operations in the Dominican Republic for a full year. The Players’ Association filed a grievance on behalf of Beltre, again seeking free agency for him. The union dropped its claim after the Dodgers inked Beltre to a lucrative three-year contract.

A major league regular by the age of nineteen, Beltre possessed a broad base of skills that led the Dodgers to believe he was a future star. At age twenty-one, he batted .290, drew 56 walks, and tallied 52 extra-base hits in 138 games. But his production cratered from 2001 to 2003, and the word “bust” began to be bandied about. Beltre’s aggregate on-base percentage over those three seasons barely topped .300, the Mendoza Line equivalent under which hitters don’t deserve a roster spot, barring huge power or other hidden talents. (See Chapter 5-1 for more on the Mendoza Line.) His best slugging average during that period was .426, a serviceable figure for a third baseman but hardly the stuff of superstars.

In 2004, however, Beltre broke out: He posted a batting line of .334 batting average/.388 on-base percentage/.629 slugging average, blasting 48 homers and flashing Gold Glove–level defense. Coincidentally—skeptics would say conveniently—the 2004 season was also his walk year. Beltre opted for free agency; executives and observers around the league pondered whether it was wise to pay him based on his 2004 performance. On the one hand, his numbers that season were wildly out of step with the rest of his career. On the other hand, many in the game had long predicted great things for Beltre—perhaps he was finally realizing his vast potential.

Dodgers general manager Paul DePodesta, who had been weaned on Billy Beane’s cold-eyed, frugal approach in Oakland, took a pass. The Seattle Mariners didn’t, lavishing Beltre with a five-year, $64 million contract. Coupled with the arrival of fellow highly paid free agent Richie Sexson, Beltre was supposed to restore winning baseball to the Pacific Northwest. But while Sexson had a big year, Beltre and the Mariners didn’t. The team went 69-93; Beltre flailed to the tune of .256/.304/.414. That was even worse than his cumulative pre-2004 numbers—if it hadn’t been for a midseason hot streak, it could have been even uglier.

The cynical explanation is that Beltre, out of brazen selfishness, willfully ramped up his production in 2004 to inflate his market value. Then, once he’d grabbed his multiyear, guaranteed contract, he indolently regressed to form. The less cynical explanation is that, as a matter of happenstance, Beltre’s career year and his walk year occurred at the same time.

In any isolated case where a player experiences a walk-year spike, there’s no way to answer the questions of motive and causation. A quandary we can tackle, though, is whether players tend to perform better in walk years than they do in seasons preceding or following their entry into the free-agent market. To do this we’ll use a Baseball Prospectus statistic called Wins Above Replacement Player (WARP). Similar to Value Over Replacement Player (VORP—introduced in Chapter 1-1), WARP measures the number of wins—rather than runs—a player contributes above what a fringe Triple-A veteran would produce, while also accounting for defense. Using WARP, we’ll compare the walk years of 212 prominent free agents from 1976 to 2000 with their immediate pre- and postwalk seasons.

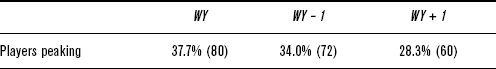

In Table 5-3.1, column “WY” will be the average WARP for all the aforementioned players in their walk years; “WY – 1” will be the average WARP for all players in the seasons immediately preceding their walk years; and “WY + 1” will be the average WARP in the seasons immediately following their walk years.

TABLE 5-3.1 Average WARP, 1976–2000, Top Free Agents

Based on these results, it does appear that players experience a cumulative performance spike in their walk years—a 9.4 percent uptick in WARP, to be specific. Of course, before we draw any firm conclusions from these data, there’s the matter of age to consider. Using the same pool of 212 players, let’s look at the average age for players in their walk years, before their walk years, and after their walk years (Table 5-3.2).

TABLE 5-3.2 Average Age, 1976–2000, Top Free Agents

These 212 players average thirty years of age in their prewalk seasons, thirty-one in their walk seasons, and thirty-two in their postwalk seasons. Studies by Bill James and other researchers show that a player most often hits his peak between ages twenty-five and twenty-nine. That makes the walk year in this study further removed from prime territory than the prewalk year. In other words, age doesn’t explain away the walk-years’ performance discrepancy.

Let’s take a closer look. Table 5-3.3 shows the percentages of players who peaked in WY, WY – 1, or WY + 1.

TABLE 5-3.3 Percent of Players Peaking in Walk Year, Before, or After, 1976–2000, Top Free Agents

According to this table, players: (1) perform better in their walk years, (2) do so at an age that doesn’t lend itself to peaking, and (3) perform better in their walk years than they do in their pre- or postwalk seasons. Whether this phenomenon is a function of accident, unconscious design, or willful self-interest is impossible to say, but the trend is manifest. Of course, WARP is a measure that’s dependent, to some extent, on playing time. It’s possible to put up better rate numbers (e.g., AVG, OBP, SLG, ERA) than another player but to have a less valuable season because of a playing-time deficit. After all, a player who slugs .550 in 250 plate appearances is less valuable than one who hits .510 in 600 plate appearances. WARP and statistics like it reflect this fact. As such, it’s possible that players, rather than actually performing at a higher level during walk years, merely soldier on, playing through minor injuries and fatigue that might have sidelined them in other seasons. Table 5-3.4 explores whether that’s the case for these 212 players.

TABLE 5-3.4 Average Games Played/Pitched in Walk Year, Before, or After, 1976–2000, Top Free Agents

Indeed, players do play or pitch in more games in their walk years, by a margin of 6.3 over their prewalk seasons and 4.8 over postwalk seasons. The bump in playing time explains away part of the walk-year WARP advantage, but, in light of what we learned about average age and the degree of the WARP edge, it’s not enough to nullify the trend completely.

If anything, these data should make organizations even more cautious on the free-agent market. Baseball’s economic structure is such that players don’t become free agents until after six seasons of major league service. Often, this means they hit the open market after their prime seasons are behind them. Also to be considered are the corollary costs of signing a prominent free agent. If a player has been offered salary arbitration by his former team and is a free agent ranked by the Elias Sports Bureau that year, then the team that signs him must forfeit—depending on the player’s rankings—one or two high draft picks to his former team. A team that regularly fritters away compensatory draft picks will inevitably thin out its farm system. Doing so, of course, exacts a cost down the road. Signing free agents who have been offered arbitration is even more costly than the contract years and dollars would lead you to believe. The upshot is that organizations had better be darn sure they’ve got the right guy.

Regardless of what a player has done in the past, teams need a dispassionate evaluation of what that player will do in coming seasons. This means taking into account not only the player’s age but also the context of his previous performances.

In the winter of 1999, the Tampa Bay Devil Rays, going into only their third season of existence and seeking to make a splash on the free-agent market, signed outfielder Greg Vaughn to a four-year, $34 million whale of a contract. What the Rays saw was a player who’d tallied 95 home runs in the previous two seasons. What they should’ve seen was a 34-year-old player who was slow of foot, defensively challenged, and burdened with “old player” baseball skills—power and walks, and little else. The result was one of several D-Ray free-agency disasters.

In Vaughn’s first season in Tampa, he posted a line of .254/.365/.499, roughly even with his .245/.347/.535 performance the previous season; but his homer total plunged, from 45 in 1999 to 28 in 2000. The next season, Vaughn hit .233/.333/.433 with just 24 homers; his .433 SLG was the worst showing among all regular designated hitters that season. The following year, Vaughn, making a career-high $8.75 million, reached new depths. Injuries limited him to only 69 games. Mercifully so, given Vaughn’s horrific .163/.286/.315 performance—numbers that, on a per–plate appearance basis, made him one of the worst hitters in all of baseball that season. In spring training 2002, Vaughn scuffled once again, and the Rays cut him, eating the $9.25 million he was owed that season. After a brief 22-game dalliance with the Colorado Rockies in 2003, Vaughn was out of baseball for good.

The most precipitous drop from walk year to the season immediately following was experienced by Nick Esasky. In 1983, Esasky replaced an aging Johnny Bench as the third baseman for the Cincinnati Reds. In 1985, he enjoyed a breakout season of sorts, hitting 21 homers in 125 games of action. In December 1988, the Reds dealt Esasky to the Boston Red Sox as part of a five-player trade. Fenway Park is a great environment for right-handed power hitters, and accordingly, Esasky thrived in his lone season in Boston. For the 1989 season, Esasky, by then a full-time first baseman, slugged .500, totaled more than 60 extra-base hits, and drew 66 walks. On the seeming strength of that season, the Atlanta Braves and then-GM Bobby Cox signed the twenty-nine-year-old Esasky to a three-year contract worth $5.6 million, just before his thirtieth birthday.

Once you adjust for the tendencies of Fenway, in what was then a more moderate era for offense, Esasky’s work in 1989 was unimpressive considering the higher offensive bar for first basemen. On the road that season, Esasky hit .253/.331/.459; at Fenway, he hit .300/.379/.541. In fact, Esasky, in the context of park and league, had never been anything special with the bat. However, in failing to leaven his numbers in Boston, the Braves and Cox overvalued Esasky.

What happened, however, no amount of statistical correction could predict. Not long after Opening Day in 1990, Esasky developed an inner-ear infection that eventually resulted in a debilitating case of vertigo. Esasky’s malady caused him unrelenting dizziness, which obviously wouldn’t allow him to play baseball. The 9 games he played for the Braves in April were the final 9 games of his career. An insurance policy covered the remainder of his contract. On the WARP front, Esasky went from a walk-year mark of 7.2 to a 1990 WARP of –0.4.

You can make a compelling case that no multiyear, high-dollar free-agent contract tendered to a first baseman has turned out to be a wise decision. That’s mostly because first basemen, as a species, don’t tend to be athletic and don’t tend to age well. The Angels were so smitten with Mo Vaughn’s résumé—which included the 1995 MVP Award and a 1998 walk year that saw him hit .337/402/.591 with 40 homers—that they signed him to a massive six-year, $80 million contract. The Angels, like so many other teams hungry for a slugging first baseman, were willing to overlook Vaughn’s age (he turned thirty-one during the off-season in which he signed the deal); his huge, cumbersome physique; and his decidedly old-player skills. After a respectable but injury-shortened 1999 in which he hit .298/.353/.508, Vaughn’s numbers dropped further the next season. Dumped on the Mets in exchange for Kevin Appier’s albatross contract, Vaughn slipped to .259/.349/.456 in 2002—a solid result for a low-priced shortstop but a catastrophe for a first baseman making more than $17 million that year. Vaughn played just 27 games in 2003, then succumbed to injury and never played again; he pocketed $34.3 million for the 2003 and 2004 seasons.

The list of disastrous free-agent first-baseman contracts runs on and on. The five-year, $85 million contract extension the Astros gave Jeff Bagwell after the 2001 season also became a boondoggle when age and a degenerating right shoulder curtailed Bagwell’s production, then forced him to miss huge chunks of time. On the Astros’ 2005 playoff roster more out of ceremony than anything else, Bagwell will cost the Astros nearly $20 million in 2006, with little hope of returning to everyday duty, let alone his old elite level of performance. Jim Thome and Jason Giambi—also barrel-chested slugging first basemen on the wrong side of thirty—looked like they might be exceptions to the free-agent first-baseman trap early in their megadeals with the Phillies and Yankees. Injuries and other ailments have all but assured a nasty ending for both. Though Carlos Delgado fared well in year one of his four-year, $52 million contract, it’s hard to like his odds of sustained stardom as he turns thirty-four, thirty-five, and thirty-six over the next three seasons. At the time of this writing, several teams were engaging in a veritable death match in an effort to sign playoff hero Paul Konerko to a long-term deal. With five- and six-year deals and huge dollars being bandied about, it’s not hard to picture Konerko becoming a big financial burden as he moves well into his thirties, declining over the life of such a deal. Given teams’ reluctance to learn these lessons, you can already squint and see some team throwing away tens of millions too much on 2005 Rookie of the Year Ryan Howard in the winter of 2011.

Not all high-dollar free-agent contracts culminate so grimly, though—if they did, even the most Steinbrennian urges would be set aside in the name of restraint. In the winter of 1992, Barry Bonds was one of the most feverishly pursued free agents in history. He was coming off a season in which he hit .311/.456/.624, swatted 75 extra-base hits, drew 127 walks, swiped 39 bags, claimed his third straight Gold Glove in left, and won his second MVP Award for the division-winning Pittsburgh Pirates. In terms of WARP, Bonds’s 1992 season was the best of his career to that point, a league-leading mark of 12.9.

After being courted by the usual deep-coffered suspects, Bonds signed a six-year, $43.75 million contract—the richest in baseball history at that time—with the San Francisco Giants, his hometown team and the club that had originally drafted him in 1982. (Rather than sign then, Bonds accepted a baseball scholarship to Arizona State; coming out of college, he was drafted by the Pirates with the sixth overall pick of the 1985 draft.)

Over the next twelve seasons as a Giant, Bonds would become the first player in history to steal 500 bases and hit 500 homers—after becoming the first player in history to steal 400 bases and hit 400 homers. He would also win five more MVP trophies; lead his team to Game 7 of the World Series; and, as of the end of the 2005 season, tally 708 career home runs.

The Giants did several things right in signing Bonds. First, they got a player who, at age twenty-eight, was young relative to other six-year free agents. Second, they got a player whose skills—an ability to hit for average, broad-based power indicators, speed on the bases, high walk totals in tandem with low strikeout totals, and excellence with the glove—figured to hold up over time and augured a promising aging curve. Third, they signed a player who, in every sense of the word, was an elite performer. Even with modest age-related decline, Bonds would still be among the best in the game. It just so happened that his finest seasons were yet to come. In four of the next twelve seasons, Bonds would beat his former career-high VORP; only twice over that span did he dip below the 10-WARP mark.

In the case of Adrian Beltre, the age was right, but the established record of performance wasn’t. In the cases of Greg Vaughn and Mo Vaughn, each had been a consistent high-level performer, but both were old, with old-player skills. In Bonds’s case, all signs pointed to success. By knowing the age at which players begin to decline, keeping a player’s recent performance in context, valuing skills that tend to be maintained over time, and being aware that the walk-year performance spike is often a genuine phenomenon, organizations can make better decisions on the free-agent market. Ignore any of those factors, and teams will make costly missteps.