What Happened to Todd Van Poppel?

DAYN PERRY

For Oakland, the story starts with veteran slugger Dave Parker, whose contract with the A’s ran out in 1989. Parker had put up rather paltry numbers that season for a corner outfielder/DH type, and he was in his late thirties. The decision from Oakland’s perspective wasn’t difficult, but Parker’s cachet as a veteran performer created a market for him. The Brewers accommodated Parker nicely and in the process forfeited a pair of compensatory draft picks to the A’s. In the June draft of 1990, the A’s would spend their glut of draft picks—four of the first thirty-six selections—on a quartet of promising hurlers who would come to be called (prematurely, as it turned out) the “Four Aces.” The Four Aces were Kirk Dressendorfer, Don Peters, Dave Zancanaro, and Todd Van Poppel, the last a fireballing Texan long on promise and press clippings.

The fourteenth overall pick, Van Poppel was widely hailed as the most gifted high school pitcher ever. It’s a historical imperative that any Texan under nineteen with a good fastball will be crowned “the next Nolan Ryan,” and so Van Poppel was. That thirteen teams passed on him that year shouldn’t suggest any divided enthusiasm; most teams simply doubted they could sign him. (He had a baseball scholarship waiting for him at the University of Texas).

But the A’s bit and, after protracted negotiations, wound up signing Van Poppel to a $1.2 million major league contract. To this day, he and Josh Beckett of the Marlins are the only two pitchers to be signed to major league contracts straight out of high school. The consequence of a major league contract tendered to a newly drafted player is that the player must be added to the major league roster within three years or be exposed to waivers. In the case of a college-trained draftee, that’s not all that risky; in the case of raw prep pitcher, it presents both parties with an unrealistic timetable.

Sure enough, Van Poppel, despite dubious command of his curve-ball, made his major league debut at age nineteen, after only thirty-two games in the minors (and on the “strength” of a stint in Double-A in which he walked 90 batters in 132.1 innings). Whether he was mishandled or was never hardwired for long-term success cannot be known; what’s beyond dispute is that he was a colossal disappointment. Van Poppel’s stuff was tremendous, but his control was terrible, and he was never able to cultivate a reliable off-speed pitch. He floundered for a decade before finally meeting with a modicum of success as a middle reliever with the Cubs. By the time he retired following the 2004 season, he had a 5.58 career ERA, had logged a 40-52 record with six different organizations and had been waived twice and released three times.

The other three aces fared even worse. Peters and Zancanaro never reached the majors, and Dressendorfer logged only seven games at that level. Still, it was Van Poppel who became, to many observers, the exemplar of squandered promise. His story and its cautionary elements raise the question: What’s the wisest way for a team to spend a draft pick?

More than any other sport, baseball’s amateur draft entails a huge amount of uncertainty. Even the shrewdest teams have been known to throw away millions of dollars on players who never panned out. So should teams focus on high school talents, who can range from a Todd Van Poppel to future Hall-of-Famer Greg Maddux? Or is it wiser to focus on college-trained ballplayers, whose realized promise ranges from who-dat Antone Williamson to all-time great Barry Bonds?

For a long time the debate was defined by received wisdom on both sides. The statistically inclined camp held that college draftees were manifestly superior, while traditionalists and scouts believed that drafting eighteen-year-olds with imposing tools better allowed an organization to craft a future superstar. Each side trotted out study after study and anecdote upon anecdote to buttress its position, but never to its opponents’ satisfaction.

So which is the better strategy—focusing on high school talents or stockpiling the system with college-trained ballplayers? The answer is somewhat fluid: Different eras, for whatever reason, yield different results. That said, Rany Jazayerli, in a 2005 series of articles on Baseball Prospectus.com, has done the most definitive research to date, scrutinizing every draft from 1984 through 1999. Specifically, Jazayerli examined the top one hundred selections from each of those drafts. After he eliminated players who failed to sign with the team that drafted them, that still left 1,526 players in the study pool, of whom 752 (49.3 percent) made the majors. To measure the quality of the draftees, Jazayerli used each player’s Wins Above Replacement Player (WARP) rating, a Baseball Prospectus metric that measures, in wins, what a player provides over a readily available “replacement-level” player for the first fifteen years of his major league career.

Here’s some of what Jazayerli discovered:

Point 1: The greatest difference in value between consecutive draft positions is between the first and second picks. Top overall picks, on average, logged a fifteen-year WARP of around 46. Second overall picks, meanwhile, posted WARPs of about 31, or less than the average of the third and fourth overall picks.

Point 2: There’s very little difference in value between second-round and third-round draft picks. Picks 41–65 (roughly speaking, the second round of the draft) on average tallied a fifteen-year WARP of 4.51, while picks 66–90 (roughly speaking, the third round of the draft) logged an average WARP of 4.56—a negligible difference.

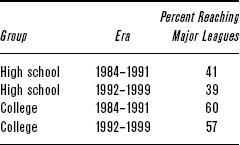

Point 3: College-trained players are about 50 percent more likely to reach the major leagues than high school players at equivalent draft positions. This advantage has remained constant over time. Broken down into eras, Table 7-1.1 shows how collegians and high schoolers compare in terms of percentage of draftees reaching the majors.

TABLE 7-1.1 Percent of High School and College Players Reaching Major Leagues

While upside can be debated, college talents are far safer bets to reach the highest level. This is because they’ve already survived a winnowing process from having played college ball in the first place. In the case of pitchers, they’ve also made it through the critical ages of eighteen through twenty, when many career-altering injuries occur.

Point 4: In a year where there’s a widely coveted superstar talent available in the high school ranks, it’s perfectly acceptable to use the top overall pick to get him.

You don’t need to look far to find elite prep performers justifying their overall No. 1 selection: Jeff Burroughs in 1969, Harold Baines in 1977, Darryl Strawberry in 1980, Ken Griffey Jr. in 1987, Chipper Jones in 1990, Joe Mauer in 2001. Spending the top overall pick on a gifted high school hitter has paid off time and again.

Point 5: Through the first one hundred picks of the draft, not only are college players about 50 percent more likely to reach the major leagues than high school players drafted in the same slot, but they also provide approximately 55 percent more value over the course of their careers. This advantage persists at every point after the No. 1 pick. From 1992 to 1999, however, the edge enjoyed by college talents slowly degrades until the two groups are almost equal, with the college set retaining a narrow and perhaps statistically questionable advantage.

Point 6: The value of high school players relative to their college counterparts has increased over time, even though teams were more likely to use top draft picks on high school players in the 1990s than in the 1980s. For instance, from 1984 to 1991, college draftees held an average fifteen-year WARP advantage of 11.15 to 6.08. However, from 1992 to 1999, that WARP advantage declined to just 6.33 to 5.22.

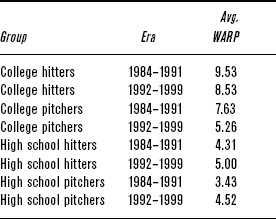

Point 7: Although the collegiate edge nearly evaporated in the 1990s, college-trained hitters remain easily the most valuable draft pick on average, enjoying a substantial edge over every other type of pick throughout the duration of the study. No matter how you massage the data, college hitters come out ahead of every other group—college pitchers, high school hitters, high school pitchers—usually by a wide margin. Table 7-1.2 shows the numbers.

Point 8: High school pitchers remain the riskiest selections in the first round. This is mostly because, unlike college hurlers, they haven’t made it through the “injury nexus.” Pitchers in their late teens and early twenties are part of that nexus, often suffering career-altering or -ending injuries to their elbows and shoulders. But the gap between success rates for high school and college pitcher draftees is much smaller than it once was. No longer is it a grave error—going strictly by the percentages—to draft a high-school hurler in the first round.

TABLE 7-1.2 Average WARP for College and High School Hitters in the Major Leagues

However, it’s still not a great idea to spend the top overall pick on a high school arm. Only twice since the June draft was instituted in 1965 has a team selected a prep-trained pitcher first overall. In 1973, the Rangers took David Clyde, who logged only 416 innings in his major league career, and in 1990 the Yankees did it with Brien Taylor, a hurler from East Carteret High School in rural North Carolina.

At the time, Taylor was considered one of the brightest pitching prospects ever to enter the draft. He came from a modest background, a trailer home in the small burg of Beaufort. His father was a mason, and his mother worked shelling crabs. Given Taylor’s blend of talent and financial need, the Yankees may have figured they’d nab a major steal at the top of the draft. It was not to be.

The Bombers’ late offer of an $850,000 signing bonus, which was more than the previous two number-one picks—Ben McDonald and Chipper Jones—had received combined, was flatly refused. Advising Taylor and his parents (or, some would say, pulling the strings) was the agent Scott Boras. Boras wasn’t yet the uberagent he would become, but he was about to help Taylor shatter the perception of an amateur having limited bargaining power.

For the Yankees, that wasn’t the worst part of the story. Brien Taylor, the man seemingly destined to save what was then a languishing Yankees franchise, the man whose eventual $1.55 million signing bonus so shocked the nation that 60 Minutes ran an entire segment about it, never pitched an inning in the major leagues.

After making his minor league debut, Taylor told the media, “In high school nobody ever got on base, so I’ve got some adjusting to do.” He had some early success in the low minors, but in a bar fight following the ’93 season, an acquaintance of Taylor’s hurled him down on his pitching shoulder, effectively ending his career. Some within the Yankees organization believed the assailant knew exactly what he was doing. The injury cost Taylor the entire ’94 season, and a series of abortive comeback attempts yielded 111 innings, 184 walks, and an 11.27 ERA. He never made it past Double-A.

In selecting Taylor, a young and unpolished yet deeply gifted long-term project, the Yankees in 1991 passed on a litany of other first-rounders, including Manny Ramirez, Cliff Floyd, Shawn Green, Dmitri Young, Scott Hatteberg, Aaron Sele, Joey Hamilton, and Shawn Estes.

Hindsight is often an odious indulgence, but it’s worth asking whether the Yankees should have known better than to slather a king’s ransom on an untested eighteen-year-old. While there’s not much of a direct cautionary tale to be found in Taylor’s travails (other than the hazards of underage pub-crawling), the prevailing lesson still applies: eighteen-year-olds, the pro-athlete mentality, and sudden cash windfalls are often a volatile mix.

Were the Yankees stupid to choose Taylor, or merely unlucky? The stakes of the amateur draft are very high. Rash, uninformed decisions can cost a team millions, and not only in bonus payments. When a league rival has Manny Ramirez swatting 40 homers a year while you’re mourning the sad case of Brien Taylor, the botched opportunity is all the more painful.

Point 9: With the exception of those chosen in the first round, high school pitchers are about as valuable as high school hitters.

Point 10: College pitchers are, generally speaking, not significantly more valuable than either high school pitchers or hitters, regardless of which round they’re selected in.

Oakland general manager Billy Beane, who was in the lower rungs of the organization back when Van Poppel was drafted, took away some valuable lessons from that fiasco. Not only did he develop an affinity for college hurlers, but he also came to prefer the pitchers who demonstrated impressive athleticism—something Van Poppel plainly didn’t.

Tim Hudson was undersized for a right-hander, but he was a tremendously gifted athlete (he was also Auburn’s best hitter and best defensive outfielder during his final collegiate season). Mark Mulder was tall and strong—the preferred build for a pitcher—but he was also graceful and quick. All the focus on Oakland’s preference for college talents overlooks the fact that the team has homed in on a prototype in recent years—the athlete who also puts up the numbers.

And there you have it. The “stathead” preference for college hitters is justified, but the disdain for high school draftees is largely without basis. Most notably, there’s nothing wrong with taking an elite prep talent with the top overall pick. Pitchers from any source tend to be worse investments than position players. And no case better illustrates the risk of investing in high school pitching than Van Poppel’s.