What Do Statistics Tell Us About Steroids?

NATE SILVER

In December of 2004, with the frenzy over the BALCO investigation at its peak, Alan Schwarz of the New York Times asked Baseball Prospectus to assist him with an analysis of Barry Bonds and Jason Giambi. The idea was to use BP’s projection system, Player Empirical Comparison and Optimization Test Algorithm (PECOTA), to compare how Bonds and Giambi might have been expected to perform based on their statistics up through 2000, against what actually happened to their careers from that point forward.

To retell the story: Entering the 2000 season, each of these players was at a career crossroads. Bonds would turn thirty-five that year—the age at which even great players can begin to struggle—and was coming off an injury-plagued season in 1999. Giambi was a slow-footed first baseman about to enter his thirties; he’d had a good season in 1999, but it looked like a career year. Instead of withering, however, both players blossomed. Giambi won the MVP Award in 2000, and Bonds set a career high in home runs, launching an upward trajectory that would see him rewrite baseball’s record books. Needless to say, PECOTA found that Bonds and Giambi had far outperformed reasonable expectations. Bonds produced 142 more home runs between 2000 and 2004 than PECOTA would have guessed and hit .339 rather than the projected .272. Giambi produced 60 percent more home runs and 50 percent more RBI than PECOTA expected.

It doesn’t take a fancy projection system, of course, to tell us that Bonds and Giambi had unusual career paths. Still, Schwarz’s article was written fairly and thoughtfully, and he let people draw their own conclusions about Bonds, Giambi, and steroids.

Upon reflection, PECOTA’s analysis may have done the sabermetric community a disservice. The analysis seemed to lend credibility to everyone’s worst fears: Players like Giambi and Bonds have benefited from steroids, not just incrementally but by a huge margin. With 142 fewer home runs, Bonds would be chasing Jimmie Foxx and Willie McCovey, not Babe Ruth and Hank Aaron. Without those extra RBI, Giambi wouldn’t have won the MVP, and the A’s wouldn’t have made the playoffs. Moneyball might never have been written.

On the other hand, lots of players have had unusual career paths, back from the days when ballplayers’ drugs of choice were Schaefer Beer and Vitalis Hair Tonic. Starting in 1953, a twenty-eight-year-old Ted Kluszewski, who had averaged just 15 home runs a season to that point in his big-league career, reeled off consecutive seasons of 40, 49, and 47. In 1973, Davey Johnson, who had just turned thirty, hit 43 home runs; he had never hit more than 18 before (and would never hit more than 15 thereafter). Even Hank Aaron defied expectations. In 1971, a season in which he missed more than twenty games, he set a career high in home runs with 47. Aaron was thirty-seven years old at the time.

It is natural to tie together cause and effect. These days, it has become just as natural to attribute any unexpected change in performance to ulterior motives. Eric Gagne adds 5 mph to his fastball? He’s juicing. Albert Pujols, who was considered a second-tier prospect, bursts onto the scene with a performance worthy of Joe DiMaggio? He’s juicing—unless he faked his birth certificate. Sammy Sosa? Not only was he juicing, he was also corking his bat, using a laser-eye mechanism in his batting helmet, and bribing the opposing pitcher to throw him hanging sliders.

This reaction is understandable. Steroids upset a lot of people—steroids ought to upset a lot of people. They ought to upset baseball researchers as much as anybody, since we make our bread and butter out of the integrity of baseball’s numbers. Nevertheless, this is one reason why sabermetricians have been reluctant to address the question of steroids. We might insist on a measured conclusion, informed by baseball’s history. But steroid use is an emotional issue, and we can’t guarantee that everyone will heed that warning.

Still, it seems likely that sabermetricians would have addressed the steroids question more aggressively if more statistical evidence existed. We know that Jason Giambi took steroids for some period of time, but we don’t know precisely when he started or precisely when he stopped. Some reports have speculated that Giambi had used steroids prior to his MVP season in 2000. But in his testimony to the BALCO grand jury, Giambi said that he had begun using the steroid Duca Durabolin in 2001. This problem has corrected itself to some degree with the significant number of minor league players (and the much smaller number of major league players) suspended for use of steroids and other banned substances during the 2005 season. In these cases, we have a specific date associated with recent steroid use and can probably assume that the player discontinued using steroids after his positive finding, which would subject him to more frequent testing and harsher penalties for a repeat violation. These data too have their imperfections. But the information is worth examining.

We can look at the steroids question by examining the indirect statistical evidence. I am very much against the notion that a sudden improvement in performance by any one particular player is necessarily indicative of steroid use. In fact, such “inexplicable” performance jumps are common enough throughout baseball’s history that it is safe to conclude that the vast majority of them have nothing to do with steroids. However, if on a macroscopic level there are more performance jumps than there used to be, that might tell us that something is amiss.

The Indirect Evidence

One way to examine this question is by looking at what I’ll call a Power Spike. A Power Spike occurs when a player “suddenly” starts hitting home runs more frequently than he used to. More specifically, we can define a Power Spike as follows:

![]() A player is an established major league veteran, at least twenty-eight years old, with at least 1,000 plate appearances (PA) accumulated among his previous three seasons; and

A player is an established major league veteran, at least twenty-eight years old, with at least 1,000 plate appearances (PA) accumulated among his previous three seasons; and

![]() The player improves upon his established home-run rate by at least 10 HR per 650 PA, in a season in which he had at least 500 PA.

The player improves upon his established home-run rate by at least 10 HR per 650 PA, in a season in which he had at least 500 PA.

We can look at the frequency of Power Spikes throughout different eras in baseball’s recent history. Although there are many permutations in how we might define such eras, I prefer the following:

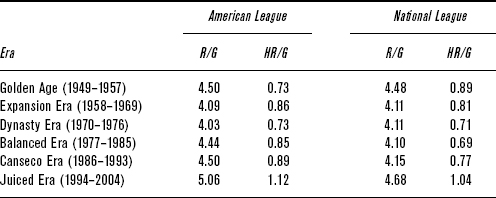

![]() Golden Age (1949–1957). Runs from the complete reestablishment of baseball following World War II until the movement of the Giants and Dodgers from New York to California in the 1958 season. A last period of stability featuring relatively high levels of offense.

Golden Age (1949–1957). Runs from the complete reestablishment of baseball following World War II until the movement of the Giants and Dodgers from New York to California in the 1958 season. A last period of stability featuring relatively high levels of offense.

![]() Expansion Era (1958–1969). Coincides with the westward expansion of baseball, the expansion in the number of franchises (from sixteen to twenty-four during this period), and the full racial expansion of the sport. The instability off the field is paralleled by instability in offensive levels, which varied maniacally from year to year.

Expansion Era (1958–1969). Coincides with the westward expansion of baseball, the expansion in the number of franchises (from sixteen to twenty-four during this period), and the full racial expansion of the sport. The instability off the field is paralleled by instability in offensive levels, which varied maniacally from year to year.

![]() Dynasty Era (1970–1976). The period immediately preceding the implementation of full-blown free agency in 1977. Three great dynasties—those of the Cincinnati Reds, Oakland A’s, and Baltimore Orioles—accounted for six of the seven World Series championships during the period and nine of the sixteen league pennants. Offense was relatively low, prompting the American League to implement the DH in 1973.

Dynasty Era (1970–1976). The period immediately preceding the implementation of full-blown free agency in 1977. Three great dynasties—those of the Cincinnati Reds, Oakland A’s, and Baltimore Orioles—accounted for six of the seven World Series championships during the period and nine of the sixteen league pennants. Offense was relatively low, prompting the American League to implement the DH in 1973.

![]() Balanced Era (1977–1985). The 1977 season was marked by a sharp increase in offense as a result of the expansion to twenty-six clubs and a new manufacturer of baseballs. The offensive improvement brought the game back into balance, and the era is remembered for the wide variety of styles that prospered during the period.

Balanced Era (1977–1985). The 1977 season was marked by a sharp increase in offense as a result of the expansion to twenty-six clubs and a new manufacturer of baseballs. The offensive improvement brought the game back into balance, and the era is remembered for the wide variety of styles that prospered during the period.

![]() Canseco Era (1986–1993). Begins with Jose Canseco’s Rookie of the Year award in 1986 and ends with the last full season before the 1994 strike. The Canseco Era saw the resumption of large year-to-year fluctuations in offensive levels. The 1987 season, in particular, featured the highest levels of run scoring seen in either league since the 1950s.

Canseco Era (1986–1993). Begins with Jose Canseco’s Rookie of the Year award in 1986 and ends with the last full season before the 1994 strike. The Canseco Era saw the resumption of large year-to-year fluctuations in offensive levels. The 1987 season, in particular, featured the highest levels of run scoring seen in either league since the 1950s.

![]() Juiced Era (1994–2004). One of the great boom periods in baseball history, along with the Roaring ’20s. Offensive levels improved sharply between 1993 and 1995, escalated further in 1999, and have remained high since then. Associated with small ballparks, small strike zones, and the allegation of widespread steroid usage.

Juiced Era (1994–2004). One of the great boom periods in baseball history, along with the Roaring ’20s. Offensive levels improved sharply between 1993 and 1995, escalated further in 1999, and have remained high since then. Associated with small ballparks, small strike zones, and the allegation of widespread steroid usage.

Table 9-1.1 provides the average number of runs and home runs produced per game in each era.

TABLE 9-1.1 Average Number of Runs and Home Runs Produced per Game in Different Eras

Tracking the number of Power Spikes is relatively simple, once we have these definitions in place. Figure 9-1.1 presents the frequency of Power Spikes per 100 eligible hitters in each of our six eras. The dashed line in Figure 9-1.1 indicates the average frequency of Power Spikes between 1949 and 1993—about 5.8 per 100 hitters. Since 1994, the frequency has increased to 9.1 per 100 hitters. Just how much emphasis you want to place on the increase is a matter of perspective. Power Spikes have been 57 percent more common during the Juiced Era than they had been previously, which is certainly statistically significant. On the other hand, some number of Power Spikes has always occurred, and the difference amounts to only a handful of “extra” Power Spikes per season.

In some sense, however, Figure 9-1.1 is telling us something that we already knew. We know that there has been an increase in home runs in recent seasons, and that somebody has to be responsible for providing those extra home runs. If home runs have become easier to hit for some reason other than steroids, be it smaller ballparks, inferior pitching, juiced baseballs, or something else, then Power Spikes will be easier to come by.

In fact, if we rerun the numbers to account for macroscopic changes to the offensive environment, then the increase in Power Spikes disappears. Figure 9-1.2 presents the same information but incorporates an adjustment for league and park effects rather than using raw totals. More specifically, all the historical home run numbers are adjusted to the standards of the 2004 American League. There were about 20 percent more home runs hit per game in the 2004 AL, for example, than there were in 1986. So a player who hit 30 home runs in 1986 is credited with 36 adjusted home runs (20 percent more). An identical technique is applied to account for park effects (Figure 9-1.2).

FIGURE 9-1.1 Power Spikes per 100 hitters in different eras

FIGURE 9-1.2 Power Spikes per 100 hitters in different eras, adjusted for park and league effects

By this definition, Power Spikes have been neither any more nor any less frequent in the Juiced Era than in previous periods. Instead, the period that stands out is the Dynasty Era of the early and mid-’70s, which interestingly enough corresponds with the widespread introduction of “greenies” (amphetamines) into major league clubhouses.

Then again, perhaps the league adjustment is not the right thing to do after all. This gets to what I call a “chicken-and-egg” problem: Are there more home runs hit because there are more Power Spikes? Or are there more Power Spikes because there are more home runs?

One way to refocus the question is to look at which hitters are responsible for the increase in home runs. Are home runs up because shortstops who look like Bugs Bunny are suddenly turning in 20-homer seasons? Because players like Barry Bonds and Mark McGwire, who were already very good, have taken their power output to unprecedented levels? Or is the difference felt universally—a rising tide lifts all boats?

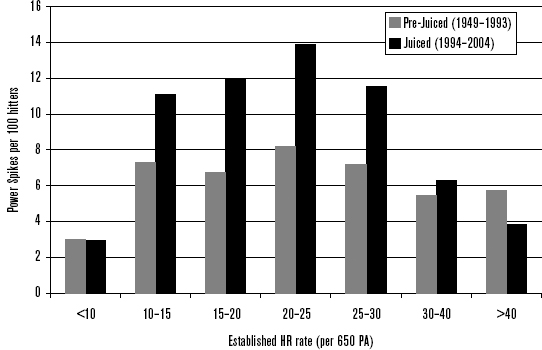

Figure 9-1.3 returns to the unadjusted data set but breaks the frequency of Power Spikes down based on the number of home runs that the player had hit previously. We call this his “established” home-run rate—his frequency of home runs per 650 PA in the three seasons before the Power Spike occurred. The figure is further broken down between the Juiced Era and the “Pre-Juiced” years of 1949–1993.

FIGURE 9-1.3 Power Spikes per 100 hitters, compared to established home-run rates, 1949–1993 and post-1993

This figure reveals something very interesting: Power Spikes have occurred more frequently in the Juiced Era, but the increase in frequency is almost entirely attributable to certain types of hitters. In particular, Power Spikes have become more frequent among hitters with average power—those guys who will hit more than 10 home runs but fewer than 30 in a typical season. Power Spikes have not become more frequent among hitters who have no power at all. It has never been very common for a hitter who has a weak, slap-hitting swing to transform into a power threat, and it is no more common today.

But there is also no increase in Power Spikes among players who were already very good power hitters, capable of hitting at least 30 home runs per year. Sometimes a very good power hitter will turn into an insanely great one, as Bonds and McGwire did. But this is no more common today than it had been previously. The players who have been most responsible for the Juiced Era home-run boom are the middle-of-the-road players: those guys who used to hit 15 or 20 homers a season and are now hitting 25 or 30.

The typical steroid user might not be the prima donna slugger who endorses Budweiser between innings but the “hardworking late bloomer” who is struggling to maintain his spot in the lineup or is trying to leverage a good season into a big free-agent contract.

Certainly these players might have more economic incentive to enhance their performance, as compared to their counterparts who have already signed multiyear, guaranteed major league contracts. Among professional athletes, the decision about whether to use steroids is not a result of locker-room peer pressure but rather a relatively rational calculation about the medical, moral, and financial costs and the risk of getting caught as compared to the potential upside. In that sense, it is just like any other form of cheating. The anonymous minor leaguer profiled in Will Carroll’s book The Juice, who used steroids at a time when he was struggling to maintain his status as a credible major league prospect, expressed this calculation succinctly: “Look, if you told me shooting bull piss was going to get me ten more home runs, fine.”

It may also be that, whether or not they are more inclined to use steroids, marginal players have the most to gain from them. Steroids are used to help a player develop his musculature and physique. It is conceivably easier for steroids to turn a relatively weaker, smaller player into a bigger, stronger player than it is for steroids to turn a player who is already very big and very strong into some sort of superhero.

At least seventy-six players in professional baseball were suspended for testing positive for the use of steroids or other performance-enhancing drugs during the 2005 season, including sixty-five minor leaguers and eleven major leaguers. The list of suspended players is revealing:

![]() The players are generally not an impressive lot. Of the sixty-five minor leaguers suspended, none made the Baseball Prospectus Top 50 prospects list prior to the 2005 season, and only one made the Baseball America Top 100 prospects list (Oakland A’s outfielder Javier Herrera, who ranked sixty-eighth). Of the eleven players suspended under the major league policy, only one—Rafael Palmeiro—has ever appeared in the All-Star game.

The players are generally not an impressive lot. Of the sixty-five minor leaguers suspended, none made the Baseball Prospectus Top 50 prospects list prior to the 2005 season, and only one made the Baseball America Top 100 prospects list (Oakland A’s outfielder Javier Herrera, who ranked sixty-eighth). Of the eleven players suspended under the major league policy, only one—Rafael Palmeiro—has ever appeared in the All-Star game.

![]() Although most people assume that hitters stand the most to gain from steroids, nearly half of the suspended players (36 of 76) were pitchers.

Although most people assume that hitters stand the most to gain from steroids, nearly half of the suspended players (36 of 76) were pitchers.

We’ll return to the pitchers in a moment, but let’s first compare the performances of the position players before and after their suspensions. In particular, we’ll use a tool called the Davenport Translations (DTs), which convert minor league performances into their major league equivalents. For example, in 2004, Milwaukee Brewers prospect Rickie Weeks spent most of the season at Huntsville in the Double-A Southern League, where he posted a raw batting line (AVG/OBP/SLG) of .259/.366/.407. The DT associated with these statistics, which adjusts for the comparative difficulty of the Southern League relative to the majors, as well as league and park effects associated with playing in Huntsville, was .240/.330/.382. Weeks made the majors as a regular in 2005, where he put up a .239/.331/.394 batting line in Milwaukee—a dead match for his DT from the previous season. (The DTs are explained in more detail in Chapter 7-2.)

The DTs do not ordinarily incorporate an adjustment for player age, but I have included one here. The reason is that most of the suspended players were young prospects, and we’d ordinarily expect a young prospect to improve his performance from season to season. If a prospect posted the same DT batting line as a twenty-two-year-old that he did as a twenty-one-year-old, he’d be losing ground relative to other players at his age, and his prospect status would dim. Thus, the DTs displayed here include an additional adjustment for the average improvement (or decline) for a player of his given age.

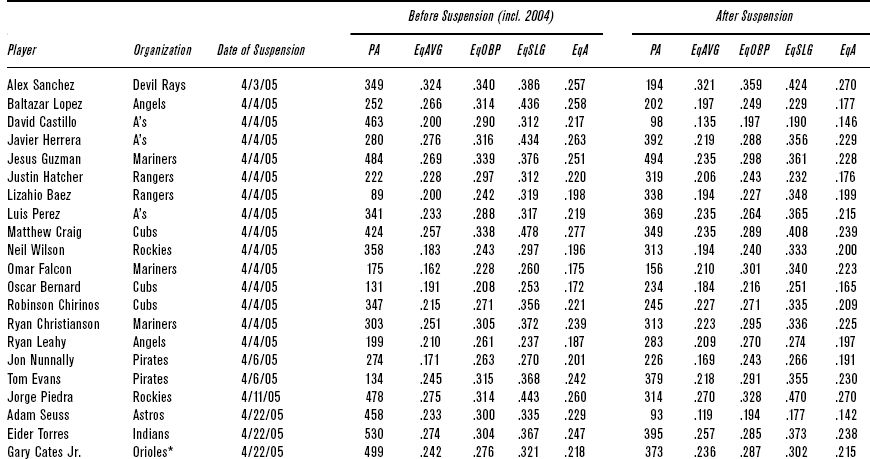

Table 9-1.2 (on the following page) presents the before-and-after comparison of the suspended players. The “before” category consists of a player’s translated batting statistics in 2004, and in any games he played in 2005 prior to his suspension, while the “after” category includes his 2005 statistics after his suspension. Note that the vast majority of players were suspended at or near the start of the season for a positive steroid test in spring training. Note also that a sizable minority of players were released after their positive tests and did not appear in organized baseball at all in 2005; these players are not included in the table. The statistics presented are equivalent AVG, OBP, and SLG as well as their companion summary statistic, Equivalent Average (EqA), which is designed to operate on the same scale as batting average but account for all facets of offensive performance (for example, a .300 EqA is a very good one, a .260 EqA is average, and a .220 EqA is poor by major league standards).

There is no immediately obvious trend here. Certainly, a few players like Herrera and Cubs third-base prospect Matt Craig posted dramatically worse numbers after their steroid suspensions. But other players actually saw their performances improve—the Devil Rays’ Alex Sanchez and White Sox’ Jorge Toca are some obvious examples. A summary of the average change in EqBA, EqOBP, EqSLG, and EqA is presented in Table 9-1.3. These results are weighted by plate appearances—more specifically, the minimum number of plate appearances between the “before” and “after” categories. For example, although Rafael Palmeiro performed terribly after his suspension, he also received only a handful of at-bats, and so his performance is not accounted for heavily in the average.

TABLE 9-1.3 Weighted Average Change in Performance Among Suspended Position Players

The players did exhibit a decline in performance after their suspensions; the change is just on the verge of being statistically significant. Interestingly, the players’ on-base percentages suffered more than their slugging averages, suggesting that steroids may affect a batter’s overall game rather than just his power output. In certain ways, this is an impressive finding.

Nevertheless, we don’t see a systematic, large-scale change. If you subtracted 14 points of OBP and 6 points of SLG from Barry Bonds’s batting statistics during his 2001–2004 seasons, he’d still have been far and away the best player in the league. That doesn’t rule out the possibility that steroids have made a much larger difference in some isolated cases, which in turn might depend on the type and quality of the steroid employed and the duration of use. But there are also probably cases in which steroids had the opposite of their desired effect: The player lost reflex speed with increased musculature, he got a “bad batch” of his drug, or the side effects outweighed the performance-enhancing benefits. For every Jason Giambi, there is also a Jeremy Giambi—the brother of the fallen superstar who also admitted to steroid use, and whose performance fell far short of expectations.

TABLE 9-1.2 Performance of Players Suspended for Substance Abuse, Before and After Suspensions

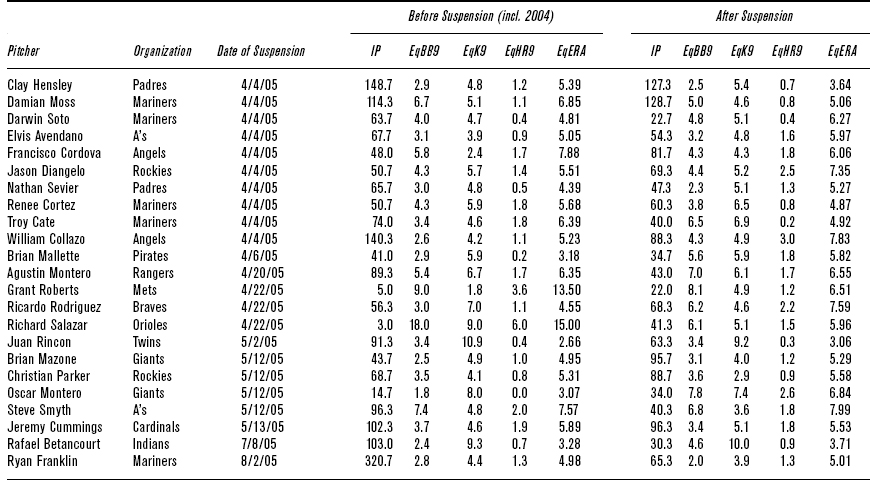

We perform the same study for the suspended pitchers in Table 9-1.4. As in the case of the position players, all statistics are based on our DT system and include an additional adjustment for player age. The categories evaluated are ERA as well as a pitcher’s key peripheral statistics: his strikeout, walk, and home-run rates per 9 innings pitched.

TABLE 9-1.5 Weighted Average Change in Performance Among Suspended Pitchers

As for the position players, there are a wide variety of outcomes following the suspension. Padres prospect Clay Hensley, suspended in spring training, had a spectacular season in 2005, going from a second-tier prospect to one of the better relievers in the National League. On the other hand, pitchers like the Braves’ Ricardo Rodriguez went from being legitimate prospects to complete washouts. The average change in performance, weighted based on the minimum number of innings pitched between the “before” and “after” time periods, is included in Table 9-1.5.

The pitchers’ performance changed in the “right” direction—they gave up a few more walks, runs, and homers while striking out slightly fewer batters after their suspension. But the effect is tiny and would not be considered statistically significant by any standard test. It also may be that we’re looking in the wrong category for a performance change. According to Baseball Prospectus’s Will Carroll, the primary benefit of steroid use for pitchers is in stamina and recovery time, meaning that the pitchers might be able to go fewer days between relief appearances or start a game on shorter rest. Thus, it might not be that steroids allow the pitcher to pitch better but that they allow him to pitch more often. It is worth noting that most of the suspended pitchers were relievers.

What We Know and What We Don’t

It is still very early in the life cycle of the steroids question. I am writing this in October 2005, just after the first season in which major leaguers were subject to suspensions for steroid use and the first season in which the names of minor league violators were disclosed publicly. Perhaps more than any other issue we’ve explored in this book, the effect of steroids is a subject that we should understand far better in ten years’ time than we do now.

TABLE 9-1.4 Performance of Pitchers Suspended for Substance Abuse, Before and After Suspensions

Nevertheless, it is worth accounting for what we can say objectively about steroids and their effects on player performance, based on the information we’ve been able to gather to date.

Unexplained Changes in Performance Are the Norm, Not the Exception

This might seem outside the scope of the steroids issue itself, but it is a tremendously important point of context. As I describe in Chapter 7-3 on player forecasting, both statheads and “ordinary” fans tend to underestimate the haphazardness of player performance from season to season. “Inexplicable” changes in performance have always been relatively common and may be the result of anything from a new batting stance to LASIK eye surgery to a tippling player finding Jesus and cutting out his drinking and carousing. More often, they may be the result of simple luck. This same caution applies at a league-wide level. While present levels of offense are high, they are not materially higher than they have been during other sustained periods in baseball history, such as the 1920s and the early 1950s.

Relatively Few Players Are Steroid Users

Eleven major league players tested positive for steroids in 2005 out of approximately 750 on major league rosters, or somewhere between 1 and 2 percent. A similarly small fraction of minor league players tested positive. This low figure may partly be the result of the deterrent effect of the existing steroids testing program and the public “outing” of violators. However, even during the 2003 major league season, when steroid tests were anonymous and there were no suspensions associated with steroid use, only about 6 percent of major leaguers tested positive. Similarly, an analysis of power breakouts during recent seasons suggests that they have become only slightly more common than in years past—no more than three or four “extra” Power Spikes per season among major league veterans. One steroid user, of course, is one too many. But there is no evidence that points to an epidemic of steroid use, as former players such as Jose Canseco and the late Ken Caminiti have alleged.

Marginal Players Are More Inclined Than Star Performers to Use Steroids

On this point, we have both direct and indirect evidence. The list of players suspended during the 2005 season contains few elite prospects and even fewer elite major leaguers. Meanwhile, the increase in home-run output in recent seasons has been almost entirely attributable to average players, who would ordinarily hit between 10 and 30 home runs per season, and not players who were already outstanding power hitters.

The reason that marginal players are more inclined to use steroids is because they stand more to gain from doing so. Baseball, like any other modern economy, is characterized by a large gap between rich and comparatively poor players. In 2004, for example, a majority of major league payroll was allocated to fewer than one hundred players, and most of this money was tied up in guaranteed, long-term contracts. Players have tremendous incentive to break into this economic elite by receiving a lucrative free-agent contract, by whatever means may be at their disposal. There is a similarly important gap in compensation between the major and minor leagues. In 2005, the minimum salary for a major leaguer was $317,000, while the minimum salary for a Triple-A player was $12,900. A player who is considered a fringe prospect will have more incentive to use steroids than one who is good enough to be essentially guaranteed a major league job.

The Average Performance Improvement from Steroid Use Is Detectable but Small

Our study of performance for confirmed steroid users during the 2005 season suggests that the effects of steroid use are small—perhaps an average gain of 10 points of AVG, OBP, and SLG for a position player. The gains for pitchers were even smaller and fell below the threshold of statistical significance. Although the effects may be much larger in isolated instances, they are negligible in most cases and may be negative in others.

![]()

Anything beyond these points is speculation. Frustratingly, this includes the question of exactly how much benefit players like Giambi, Palmeiro, and Bonds have derived from using steroids. We cannot rule out the possibility that these players have gained tremendously from steroids. There may be a few players for whom steroids represent a “tipping point,” allowing a relatively minor gain in muscle strength, bat speed, or recovery time to translate into a dramatically improved performance.

However, it is best to reserve judgment on these players. Not in the “innocent until proven guilty” spirit; the evidence that Giambi, Palmeiro, and Bonds have used steroids would hold up in a court of law (though Bonds has testified that he used one such substance contrary to how a player seeking performance enhancement would use it). Rather, I mean it in the conservative sense of the scientific method: We cannot reject the null hypothesis that the spectacular performances of players like Barry Bonds is the result of something far different than steroid use, such as good, old-fashioned determination and hard work. One of the beauties of baseball is its unpredictability. Every time we thought we’d seen everything, we see something else, whether it’s the Red Sox and White Sox winning the World Series in consecutive seasons or a thirty-six-year-old shattering the home run record. In the Juiced Era, we have the right to be skeptical, but it would be a shame if we’ve become so cynical that we can no longer enjoy these achievements.