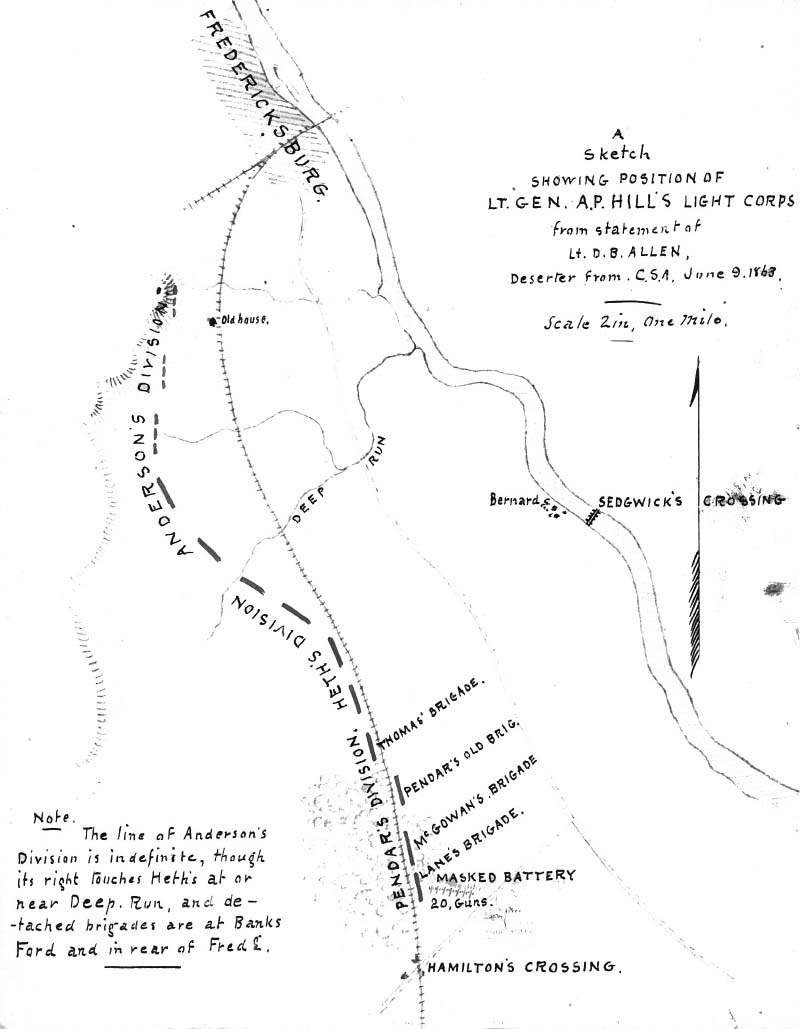

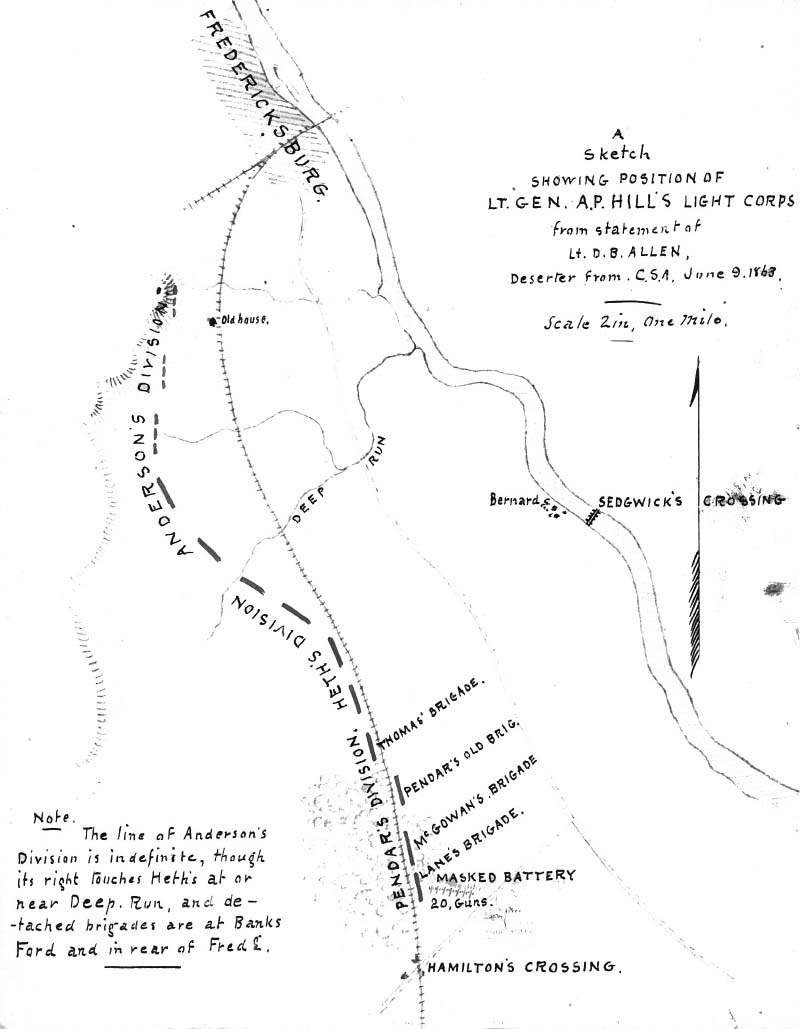

Sketch showing position of Lt. Gen. A. P. Hill’s Light Corps, June 9, 1863, drawn by John C. Babcock, BMI. Courtesy Huntington Library.

After Chancellorsville, Lee did not rest on his laurels. He sought to follow on the heels of his victory with an invasion of the North that could settle the war by defeating the Army of the Potomac on its own ground, seize Baltimore or Washington, and at worst strip the rich fields and barns of Pennsylvania in order to spare a ruined Northern Virginia another levy to support his army in the coming year. With Jefferson Davis’s permission, he reinforced the Army of Northern Virginia by 50 percent to 75,000 men, with brigades and divisions that had been in garrison of the ports and forts along the eastern seaboard of the South. On May 30, he increased the number of his corps from two to three, by creating III Corps and assigning Maj. Gen. A. P. Hill to its command. In Jackson’s old II Corps, he appointed Richard Ewell, who had been out of action for more than a year after losing a leg in battle.

Lee’s invasion plan was strategically elegant but simple. He would march his infantry corps up the Shenandoah Valley, cross the Potomac, and march through western Maryland and into the heart of Pennsylvania. His march would be shielded by the Blue Ridge Mountains in Virginia and its continuance in Maryland and Pennsylvania called South Mountain. His cavalry would ride east of the mountains to block the passes to shield that movement. Once in central Pennsylvania, he could threaten the state capital, Harrisburg, as well as Philadelphia, Baltimore, and even Washington. With any luck, he would steal such a march on the still-stunned Hooker and be in Pennsylvania before the Army of the Potomac stirred from its camps just south of the Potomac between Alexandria and Leesburg.

He would be doing that, however, with a reorganized and expanded army that had not had time to shake down into a cohesive force. Two of his three corps commanders and half his division and brigade commanders would be new in command of their formations. He had not made the mental adjustment in his command style that such a cast of new leaders required. He continued to rely on the very personal and intuitive relationship he had had with Stonewall Jackson and Longstreet, whose well-judged initiative could be consistently relied on. He would find that Lt. Gens. Ambrose Powell Hill and Richard S. Ewell did not measure up to that standard.

Hooker still smarted from his drubbing at Chancellorsville. That drubbing had made him shy of another go at Lee in the immediate future. Bad timing, then, is probably a good reason why Hooker turned down his young aide-de-camp’s idea of a raid on Richmond. Captain Dahlgren submitted the outlines of such a plan to Hooker on May 23 at Falmouth. He wanted to wait until the Confederate cavalry was otherwise engaged and take the 6th U.S. Cavalry, cross the Rappahannock and Rapidan, dash south to Richmond, burn the arsenal at Bellona, and ride through Richmond, then south to Petersburg and to the safety of Union forces around Suffolk. The plan did not seem to have any great objective other than counting coup on the Confederacy itself by riding hell bent for leather through its capital. Interestingly, he added, “I know several men in the provost marshal’s service who feel confident of guiding such an expedition, and have offered to do so.” Dahlgren’s association with the BMI was obviously more than just the casual acquaintance of men on the same staff if he was discussing such an operation with them. It has the ring of just the sort of derring-do that men like Cline and Carney would relish. It is doubtful that Dahlgren would have introduced the willingness of BMI men to participate in the adventure without the at least tacit approval of its director. A lack of boldness was not one of Sharpe’s failings.1

As this episode indicated, the command’s reluctance to contemplate aggressive action did not extend to Sharpe. He continued to actively scout the enemy and to run his agent line behind enemy lines in Virginia. On the same day Dahlgren submitted his plan to Hooker, Patrick, turned over some $3,300 in Confederate currency captured by Pleasonton to Sharpe, “to use on the other side.” He would need the cash to keep the “other side” productive. Something was up.2

Sharpe was on to the reinforcement of Lee’s army between mid-May and mid-June. Sharpe’s first definite information came from a deserter who alerted him that the enemy had received orders for a long march. Surprisingly, the deserter was a fellow New Yorker, a recent immigrant to the South, and from Sharpe’s hometown as well. Sharpe’s suspicions had been aroused because Lee had been sending bogus deserters with false information in the form of men born and raised in New York in the hope that Butterfield and Patrick would find fellow Empire State men more believable. Information from other sources, such as Southern newspapers and reports from signalmen, balloonists, and agents, flowed in to form a corroborating picture. On May 27 Sharpe presented Hooker with a comprehensive and accurate assessment of Confederate troop movements, but the most important information was his assessment of the enemy’s intent. It was an impressive all-source effort. (See Appendix J for the full report.)

The Confed. Army is under marching orders and an order from General Lee was very lately read to the troops announcing a campaign of long marches & hard fighting in a part of the country where they would have no railroad transportation.

All deserters say that the idea is very prevalent in the ranks that they are about to move forward upon or above our right flank.3

What Sharpe was not able to do at this time was produce an accurate update of the order-of-battle and strength of the Army of Northern Virginia. The scale and speed of its reorganization, reinforcement, and movements created a situation that was too fluid to fix. At the same time, his right-on assessment of the enemy’s intent failed to have any timely impact on the authorities in Washington because there was an inexplicable delay of almost two weeks from its dispatch to its arrival in the capital. Lee, at least, was in a worse situation. He wrote to President Davis of the near total failure of his intelligence operation. But his security effort was working well. His picket system around his main infantry corps was so thickened that Sharpe’s scouts could not penetrate it.

That itself was an indicator, as Babcock would have noticed, since the same ploy had presaged a successful attempt in 1862 to steal a march on the Federals. Although Sharpe’s scouts could not penetrate Lee’s picket barrier, his other all-source elements filled the gap. Balloonists, Signal Corps observers, and Union pickets began noting extensive movement of Rebel forces. On June 5 a contraband claiming to be the body servant of Major General A. P. Hill, commander of the newly formed III Corps, was captured and interrogated between Hagerstown and Frederick, Maryland. He revealed that he had overheard Hill tell his officers of the planned invasion of Pennsylvania by a route west of the Blue Ridge Mountains. Sharpe was skeptical at first but became more convinced when the contraband’s story proved unshakeable. With no other information to corroborate the story, he tucked it away as a puzzle piece that might find its place a little later.4

Years later another scout, William J. Lee, would recall that “In order for Lee to get his army across the river it was necessary for him to take his pontoons from Richmond to Staunton, and from there on to the old ferry site…” He had learned that “Every engine, freight car, and coach in Northern Virginia was pressed into service to move the army and the supplies.” Lee made three trips between Richmond and Mineral City, now called Tollersville, gathering information that he thought would be useful. He would meet scout Edward McGee in Staunton, and from there McGee would take the information to the Potomac and pass it to a waiting steamer, which took it to Washington. On the way, McGee would pass his Unionist father’s farm and get a fresh horse. Whether or in what form this information reached Sharpe and Hooker is unknown, but it would have clearly contributed to the general picture that Sharpe had presented.5

Sharpe’s life was not entirely consumed by the observation of Lee. With his family in Washington, he found opportunity to visit them. He was also able to bring his wife, Caroline, to camp for visits on occasion, much to the distress of Patrick who noted how his deputy flaunted the regulations on bringing wives to camp. They made the rounds of friends, and in the manners of the time, both left their calling cards, as Colonel Gates noted when they dropped by his headquarters in his absence.6

Sketch showing position of Lt. Gen. A. P. Hill’s Light Corps, June 9, 1863, drawn by John C. Babcock, BMI. Courtesy Huntington Library.

Ominously, reports of a heavy concentration of Stuart’s Cavalry Division at Culpeper were piling up as well. The build-up had all the signs of presaging one of Stuart’s great cavalry raids that has so often humiliated the Union army. On June 6 McEntee had reported that Stuart had held a grand review of his cavalry at Brandy Station. On June 7 Sharpe reported to Hooker, “I respectfully suggest that a force of the enemy’s cavalry, not less than 12,000 and possibly 15000 men strong are on the eve of making the most important expedition ever attempted in this country.” Interestingly, a correspondent for The New York Times wrote a letter dated, “Headquarters Army of the Potomac June 8,” that repeated much of the details of Sharpe’s report and speculated that Stuart’s intention was to “make a grand raid into the North … Of the direction of Stuart’s march my information is not definite,” but then goes on to say whatever it is will take him “into Maryland and Pennsylvania.” It appears that Sharpe or someone else at headquarters had taken this correspondent into his confidence enough to brief him and show him the report with the intention that it be published.7

Hooker resolved to launch a spoiling attack on Stuart, and his timing was unintentionally perfect. The Cavalry Corps, under its new commander, Major General Alfred Pleasonton, attacked Stuart in his camps at Brandy Station on the morning of the 9th, the very day Stuart had planned to cross the Rappahannock at Beverley Ford. Noteworthy, in this, the greatest cavalry battle ever to be fought in North America, was the conduct of one of Sharpe’s fellow staff officers, the 20-year-old Ulric Dahlgren. He received the honor of being “praised in dispatches.” Pleasonton’s after-action report was effusive in its description of his conduct:

Captains Dahlgren and Cadwalader, aides-de-camp of Major-General Hooker, were frequently under the hottest fire, and were untiring in their generous assistance in conveying my orders.

Captain Dahlgren was among the first to cross the river and charged with the first troops; he afterward charged with the Sixth Pennsylvania Cavalry when that regiment won the admiration of the entire command, and his horse was shot four times. His dashing bravery and cool intelligence are only equaled by his varied accomplishments.8

Dahlgren wrote his father of the charge:

We charged General F. H. Lee’s brigade up to General Stuart’s headquarters, and within one hundred yards of their artillery … This brigade was drawn up in mass in a beautiful field one-third of a mile across—wood on each hand. On their side was a ridge, upon which was posted the artillery, and near a house in which Stuart had his headquarters. We charged in column of companies. When we came out of our woods they rained shell into us, and, as we approached nearer, driving them like sheep before us, they threw two rounds of grape and canister, killing as many of their men as ours; upon which they stopped firing and advanced their carabineers. All this time we were dashing through them, killing and being killed; some were trampled to death in trying to jump the ditches which intervened, and, falling in, were crushed by others who did not get over.

Dahlgren and the regimental commander were jumping a ditch when both their horses were cut out from under them by canister. Stunned for a moment, Dahlgren gathered his wits quickly enough to see the regiment turning about as the Confederates converged to surround it. He gave his horse a “tremendous kick,” which brought the animal to its feet as he spurred it out of the trap barely in time to avoid capture. More would be heard of this beau sabre in the coming campaign.9

Stuart’s planned departure on the eve of Pleasonton’s attack, however, was not the precursor to a great raid but to shield the movement of Lee’s infantry into the Shenandoah. The Union cavalry completely surprised Stuart, who was lucky to pull offa draw. But Hooker’s spoiling attack had succeeded in two ways. First, it delayed Stuart’s departure by a week. Second, it had brought down such criticism on Stuart for his handling of the affair that he was determined to redeem himself in the subsequent drive north, a motivation that would trump his good judgment. Sharpe was about to add injury to insult by personally going to Alexandria, Virginia, to interrogate and parole prisoners captured by Pleasonton at Brandy Station.10

On June 11 McEntee reported on a contraband captured and brought through the lines by one of his scouts. “A captured contraband, who was at Culpeper Court-House last Monday [June 8], states that Hood’s division was there, and that infantry was arriving in great force. The enemy have infantry picket all along the river to-day.”11 The next day he discovered another contraband that had come over from Culpeper. To his amazement, the young man, named Charlie Wright, had a surprisingly good knowledge of a dozen enemy regiments which McEntee cross-checked and confirmed. Wright reported the concentration of Lee’s infantry corps around Culpeper. This was corroborated by another contraband that had been brought through the lines by one of Sharpe’s scouts. On the 12th he reported: “A contraband captured last Tuesday [June 9] states he had been living at Culpeper CH [Court House] for some time past. Saw Ewell’s Second Corps passing through that place destined for the Valley and Maryland. That Ewell’s Corps had passed the previous day to the fight [Brandy Station] & that Longstreet was then coming up.”12

A second, then third, message from McEntee, each with more impressive detail of Wright’s knowledge of the troops passing through Culpeper, finally convinced Hooker that the army must be put in motion to the east of the Blue Ridge, thus paralleling Lee’s movement on the other side of the mountains. The result was that on June 13 the Army of the Potomac began to respond to Lee with a general movement north, even before two of three of Lee’s corps (Hill’s and Longstreet’s) were yet to pass through Culpeper on their way to Pennsylvania.13

Now, with Sharpe desperate to make sense of the enemy’s movements, Hooker’s failure to convince all his major commanders that they were part of the same intelligence system was again about to harm the army’s ability to respond to the enemy. McEntee found that his scouts were being arrested by the cavalry when they tried to return through Union lines even with the proper passes and that his access to prisoners and captured documents was restricted. The priceless Charlie Wright was lost to further possible use as an agent when he disappeared into the cavalry’s POW system. McEntee was beside himself as he watched cavalry officers reading captured mail for laughs before discarding often valuable documents such as company rosters. He also found his scouts commandeered by the corps commander to act as guides and couriers.

Sharpe’s task had become immensely more difficult now that the theater of operations had been vastly expanded. The limits of the BMI’s ability to function had been exceeded simply by the geographic scale of operations. A corresponding intelligence organization at the national level in Washington was needed to coordinate intelligence across the entire Middle Atlantic states region. Its absence would be sorely felt. Secretary Stanton and Chief of Staff Halleck, and even Lincoln, at times, became personally involved in attempting to coordinate intelligence to support the army, but the absence of a trained staff at the national level was painfully obvious. Stanton wired Hooker, “You shall be kept posted upon all information received here as to the enemy’s movements but must exercise your own judgment as to its credibility.” Lincoln himself followed this up with a wire that said the superintendent of the telegraph office was sending everything he received to Hooker.14 In other words, without a trained intelligence staff to conduct proper analysis, Washington would be dumping a huge amount of raw information on Hooker and Sharpe. At this time, for want of a Washington-level patron, the Balloon Corps was disbanded. Its absence at Gettysburg would narrow victory’s margin. Nevertheless, even in its absence it proved an advantage, for the Confederates went to extraordinary measures to conceal their artillery and infantry march routes because of the fear of observation they had acquired from the Balloon Corps’ efforts.15

At this juncture the personal initiative of those outside Hooker’s direct command came to the rescue. Brigadier General Daniel Tyler, commanding the garrison at Harper’s Ferry on the Potomac in Maryland, with great initiative and zeal was employing every collection means at hand to gather and forward much useful information to Hooker’s headquarters.16 Major General Darius Couch, who had been Hooker’s second-in-command at Chancellorsville, and now commanded at Harrisburg, also was determined to reinforce the intelligence effort. Among the numerous groups of scouts he organized in Pennsylvania was one under the leadership of a local notable, David McConaughy, the founder of the cemetery around which the coming battle would be fought. By June 16 McConaughy had found and reported Lee’s cavalry advance at Greencastle in Pennsylvania, barely 25 miles from Gettysburg. Scouts sent out from the military commander in Baltimore also found Lee’s cavalry the next day. Uncoordinated as their efforts were, the aggregate of patriotic and intelligent initiative started to pay off.17 Other citizens were showing their patriotism in acts of defiance, which, though they did not add to the intelligence picture, at least reminded the Confederates they were in hostile territory. One woman had pinned an American flag across her bosom and flaunted it to the passing Rebel ranks. As the Texas Brigade marched by, one man cautioned her, “Take care, Madam. For Hood’s boys are great at storming the breastworks when the Yankee colors are on them.”18

Sharpe also determined to break through Lee’s security. He sent off Sergeant Cline and a party of scouts to pass through the Union cavalry and find their way into Warrenton to locate Longstreet. So far Stuart’s men were doing a better job. On June 17 they had captured Meade’s acting signal officer, Captain B. F. Fisher, out on a reconnaissance near Aldie right under Pleasonton’s nose.19 The opportunity to turn the table on Stuart arose with the arrival of Hooker’s orders to Pleasonton also on the 17th which directed that “you leave nothing undone to give [to Sharpe’s men] the fullest cooperation.” His orders also repeated the verbal message he had already dispatched through his aide, Captain Ulric Dahlgren. It directed, surely at Sharpe’s urging, the cavalry to break through the enemy’s pickets regardless of loss “to give him information of where the enemy is, his force, and his movements.” Cline and his party arrived at the same time and were quickly integrated into the attack plan. The cavalry promptly attacked the Confederates at the pass through the Bull Run Mountains at Aldie, Virginia. In the fighting they assisted Cline and his scouts surely in Confederate uniform to join the rear of a retreating Confederate cavalry brigade. Sharpe had achieved the penetration of Stuart’s cavalry that Lee’s tight security had so long prevented.20

Sharpe employed another artful expedient this time. In a lecture after the war, Brigadier General Kilpatrick recalled the tension in the army as events were unfolding and Sharpe’s anxiety to pin down Lee’s intentions. Sharpe personally crossed the Rappahannock below Fredericksburg to make contact with a “colored washerwoman, whose cabin was in sight of our most powerful field glasses.” The woman’s husband sold food in the Confederate camps of Hill’s III Corps.

[T]he instant he saw any signs of the enemy breaking camp he was to hurry home and tell his wife to put up red cloth for artillery, a blue one for infantry, and a white towel for cavalry, his wife to place them on the north end of the clothesline if they started north, in the middle if they went west, and at the southern end if going south. Taking a favorable outlook, Gen. [then colonel] Sharpe waited with the breathless anxiety the result of his daring scheme, and just at daybreak saw a red cloth on the north end, then another, then a blue one, and then a towel, until the whole north end was full, when he hastened to headquarters with the news that the whole rebel army was marching north. This timely information was afterwards confirmed by scouts…21

The movement of Hill’s Corps was especially important because its camps south of Fredericksburg were the furthest south of Lee’s army. Once they moved, he knew that the entire army was in movement.

In the midst of this fluid and highly charged situation, Sharpe found he had to deal with an increasingly difficult commander who disregarded his analysis and began to treat him in a contemptuous manner. Hooker, whose confidence had never recovered from the beating Lee had given him in May, was showing the strain and becoming more and more erratic as he lashed out at the very man who then had put victory in his grasp. Brigadier General Patrick noted that Hooker could not make up his mind what to do to counter Lee’s movements. An order had gone out on the morning of the 17th to put the army in motion but was then countermanded. He wrote in his diary on the same day:

[Hooker] acts like a man without a plan and is entirely at a loss what to do, or to match the enemy, or counteract his movements. Whatever he does is the result of impulse, now, after having failed, so signally, at Chancellorsville … He has treated our ‘Secret Service Department’ which has furnished him with the most astonishingly correct information, with indifference at first, & now with insult.22

This was not staff backbiting but the observation of a man who was in daily contact with both Hooker and Sharpe. In fact, all three shared the same sleeping tent. Sharpe, who was in daily close communication with Patrick, must have unburdened himself to his nominal boss.

By June 20 the picture of Lee’s deployment was becoming clearer. A mass of confusing information was yielding to painstaking all-source cross-checking and corroboration. Important pieces of information came from Sharpe’s scout, Mordecai P. Hunnicutt, who had slipped into Richmond. Hunnicutt was a perfect example of the type of man Sharpe picked for his scouts. He spent his early years in the area south of Richmond and joined a volunteer regiment to fight in the Mexican War. Ten years later he joined William Walker’s failed filibustering expedition to Central America and instead ended up as a pastry chef for the president of Costa Rica. Back in the United States, he took part in the fighting in Bloody Kansas before the Civil War and later enlisted in an Ohio infantry regiment in 1862.

Finding regular soldiering not to be of his taste, he positively leapt at the chance to volunteer for Sharpe’s scouts. And Sharpe had the good sense to snap him up. Sharpe had sent him earlier on a mission to penetrate Richmond and learn what he could. Posing as a Union deserter, he enlisted in a Tennessee regiment in Virginia which got him to Richmond. He left on June 9, and in order to skirt the moving mass of Lee’s army, moved by way of western and southwestern Virginia to Charleston in West Virginia, where he reported in to the local Union commander. That officer was so suspicious of him that he wired Sharpe for confirmation of his identity before forwarding Hunnicutt’s report. Sharpe was able to filter out the errors in reporting Pickett’s order-of-battle, but found several pieces of extremely useful information. The defenses of Richmond had been stripped to the bare minimum to defend the city from any attack by Maj. Gen. John Dix at Fort Monroe. Lee’s strength had been increased to 85,000, which was about 10,000 too high. The third item was of a higher order than the order-of-battle numbers he had discovered. It addressed Lee’s intent. He overheard from a corps staff officer that “The present move is to divide our forces and dash into Washington.” This last would have to be weighed as more became known of the enemy’s movements.23

Sharpe wrote his uncle that “I need scarcely add that the two armies are maneuvering for the best position, and that Lee was “trying to get upon the old field of Manassas. He must whip us before he goes in force to Md. or Penna. If he don’t, we propose to let him go, and when we get behind him we would like to know how many men he will take back.”24 But the one element of the picture that remained opaque was the location of Longstreet’s Corps, which was the key to discerning Lee’s objective. This only added to Hooker’s stress, for Longstreet’s Corps was the mightiest offensive force in American history. Hooker’s mental state continued to distort his judgment. Patrick’s diary entry for the 19th became even more scathing:

We get accurate information but Hooker will not use it and insults all who differ from him in opinion. He had declared that the enemy are over 100,000 strong. It is his only salvation to make it appear that the enemy’s forces are stronger than his own, which is false & he knows it. He knows that Lee is his master & is afraid to meet him again in fair battle.25

By now Sharpe apparently had lost all confidence in Hooker. He had already sent his family home to Kingston from Washington. Some clash with Hooker may have been reflected in Patrick’s diary entry. Now Sharpe asked to be returned to the command of his 120th New York. He may well have felt that his contribution at army headquarters was so circumscribed by Hooker’s state of mind that his usefulness was over He wrote his uncle that he had not replied to his recent letters, “but I have not the heart for it. I am too ‘near the throne’ to say much and yet I cannot help feeling what transpires so closely to me and all of which I know so well.” Sharpe was clearly trying to write between the lines because his natural sense of prudence and loyalty prevented him from going into detail about what was going terribly wrong at headquarters. Hooker may have had a keen appreciation for intelligence, but in his state of mind he forgot that in Sharpe he had an intelligence chief with many talents, and one of them that especially worked in Hooker’s favor at this time was that he could keep his mouth shut. Unlike so many officers in the Union army who thought the service was fair ground for cutthroat politics, Sharpe, who had sound political instincts himself, was also profoundly loyal. He concluded that, if Hooker would not let him do his job, then at least he could find useful duty in command of his Ulster and Greene Counties men. Twice he requested to be returned to his regiment. Each request was denied, and Sharpe found himself shackled to a commander fast losing his nerve.26

Hooker’s state of mind may be partially explained by the flood of mostly inaccurate information he was getting from the cavalry who continued to operate in competition with the BMI. However, a major cavalry attack on Stuart on June 21 allowed Sergeant Cline and party to slip back into Union lines. He was able to identify Longstreet’s concentration near Berryville, 20 miles south of Harper’s Ferry.

The day before, Butterfield had taken a vital step in creating a near real time communications and intelligence system.

On 20 June, by direction of the chief of staff, two signal officers were assigned to each army corps. Communication was opened by flag signals between the First Corps headquarters, at Guilford Station, the Eleventh Corps at Trappe Rock, and the Twelfth Corps at Leesburg. The officers at the last-named point worked successfully also with the signal station at Poolesville, Md., and through it with those at Sugar Loaf Mountain, Point of Rocks, and Maryland Heights direct to the commanding general at Fairfax Court-House, giving to him at the same time a rapid means of communication with all the corps named above. A reconnaissance was made for General H. W. Slocum by the signal officers attached to his command.27

Lee had nothing like this system.

Sharpe was finding out that the trouble with Pleasonton was that sometimes his reports were accurate. In the mass of confused reporting there were the occasional flawless gems. He reported to Hooker on June 20, “I have been attacking Stuart to make him keep his people together, so they cannot scout and find out anything about our forces.” He reported that cavalry east of the Blue Ridge was a covering force. “Longstreet has the covering of the gaps, and is moving up his force as the rebel army advances toward the Potomac…. Lee is playing his old game of covering the gaps and moving his forces up the Shenandoah Valley.” Pleasonton was full of confidence in his men’s performance and requested on June 20 the permission “to take my whole corps to-morrow morning, and throw it at once upon Stuart’s whole force, and cripple it up.”28

Hooker approved and ordered Maj. Gen. George G. Meade, commanding V Corps, to provide infantry support. Pleasonton pitched into Stuart the next morning and “steadily drove him all day, inflicting heavy loss at every step. I drove him through Upperville into Ashby’s Gap and assured myself that the enemy had not infantry in the Loudon Valley… I never saw the troops behave better or under more difficult circumstances. Very many charges were made, and the saber was used freely, but always with great advantage to us.” Pleasonton had just hammered Stuart back into the gap he was supposed to block in any case, but Stuart had resisted the temptation to replay Brandy Station and instead had stuck successfully to his blocking mission. He reported to Lee that since the day was the Sabbath, “I recognized my obligation to do no duty other than what was absolutely necessary,” and to rest his men. He had a more practical reason as well, noting that had he attacked, he would have met not just the Union cavalry but a strong force of infantry and artillery as well, “and the result would have been disastrous, no doubt.” Pleasonton admitted that Stuart still held the gap, noting, “Stuart has the Gap covered with heavy Blakelys and 10.-pounder parrots.”29

In the same message announcing his success, he stated that “Ewell’s Corps went toward Winchester last Wednesday.” Every newspaper in the country had already reported that Ewell had overrun the Union garrison in Winchester in a stinging defeat on June 15, something Pleasonton was obviously unaware of. Hooker’s penchant for holding information close to the vest was keeping his corps commander seriously uninformed, which was especially dangerous for the Cavalry Corps screening the army and attempting to penetrate the enemy’s own screen.30

Pleasonton’s haphazard intelligence collection was now to drop some appalling analysis on Hooker and Sharpe. On June 22 he reported, based only on the statements of two deserters, that “Lee is at Winchester and that Longstreet’s troops were on their way to that place; that A. P. Hill’s corps was on the road up from Culpeper, on the other side of the mountains…” Lee was actually at Berryville, southeast of Winchester. Longstreet was still some distance from Winchester, having just withdrawn from the Blue Ridge, where he had come to support Stuart’s defense against Pleasonton’s attack. Hill’s lead division had already arrived in Berryville to fall in behind Ewell on the march north. Pleasonton had already placed Ewell near Winchester, when Ewell had Rodes’s Division already across the Potomac between Hagerstown and Sharpsburg. That same day Lee gave Ewell orders to cross the rest of his corps over the Potomac and head for the Susquehanna River in northern Pennsylvania. He himself with Hill’s Corps would depart Berryville the same day.31

While McEntee was finding Charlie Wright, Babcock had arrived in Frederick, Maryland, on June 19 with a detachment of scouts on a special mission. He had assumed the cover of a reporter for the New York Herald. It was a good cover, for the Herald was an intensely antiwar and anti-Lincoln newspaper and one that Sharpe thought maintained a “usual character for lying.” Sharpe had determined on the 17th that he needed a trusted agent and executive on the spot to report on the crossing of Lee’s army into Maryland. Officially, Hooker exercised no command north of the Potomac, but Sharpe was taking the initiative to put his people in place. Frederick was a regional communications center, and the nearby South Mountain range gave vital observation for the area. On June 20, Hooker sent him detailed instructions which he had already put into effect. He was anxious that Babcock “employ only such persons as can look upon a body of armed men without being frightened out of their senses” and “Send me no information but that which you know to be authentic.” He need not have worried; Babcock knew his business and wired Hooker back that he had already anticipated those instructions.32

That afternoon, at 3:30 p.m., Babcock again wired Hooker, this time that Rodes’s Division of Ewell’s Corps and Jenkin’s Cavalry Brigade were all the forces that had crossed the Potomac at Williamsport, with most of the infantry at Charlestown. Ewell had left Williamsport for Harper’s Ferry. The rest of Lee’s army was not within supporting distance. Two hours later he sent a hurried wire that “Signal corps just driven in; and are flying through the town. Report that the enemy are 3 miles out. Everything in an uproar, and everybody leaving. I suppose I must go too.” He added that he would go to Monococy Junction and return when he could. Even in a crisis he smelled advantage. “It is only a raid, and may prove beneficial to me, as I can learn much on returning after they have left.”33

But things were about to get worse. He found himself trapped in Frederick. With the telegraph too dangerous to use, he sent off a letter to Sharpe:

[T] wenty-five of the 1st Maryland Cavalry made a dash into the city. I tried to get out but found all the approaches picketed and gave it up as dangerous. I have been dogged about all day as a suspicious character by several notorious rebels… I had sundry papers about me stating in very strong terms my business here. Being at the time the rebel cavalry entered, in front of the Central House, a notorious rebel hole, I could not hide my papers and had to carefully destroy them by piece-meal and throw them away. A large crowed having collected I made my escape from the parties on my track and put up in a private house in a remote part of town.

The danger did not dampen his sense of humor, as he penned, “I am not over-anxious to be ______,” putting in place of the blank a sketch of a man on the gallows. Nevertheless, the danger was real. The Confederates that had ridden into town were Maj. Harry Gilmore’s 1st Maryland Battalion, attached to Fitzhugh Lee’s Brigade. Gilmore’s men shifted back and forth between partisan and regular warfare and were particularly hard on anyone they discovered as a spy. Babcock was certainly not going to put them to the test. The next morning he slipped through the pickets on a railroad handcar in the direction of Baltimore, hired two men to take him further until he could find a telegraph office to communicate with Sharpe through the War Department in Washington.34

His efforts had not been entirely in vain. He had performed the vital service of locating Ewell’s movement across the Potomac into Maryland. Pleasonton had located Longstreet’s brigades supporting Stuart’s attempt to shut off the gaps to prying Union eyes. The greatest coup was carried off by Sergeant Cline and his scouts. After having slipped into the enemy rear in civilian clothing, they had moved freely among the Southern troops masqueraded as Confederate partisans, and four days later slipped out again with a wealth of information and were in Sharpe’s tent in Fairfax late at night on June 22. Sharpe reported the next day that Cline had found “Divisions of Pickett and Hood lying in rear of Snicker’s Gap, in position to defend it. Three companies of infantry at Millwood, opposite Ashby Gap, and the rest of Longstreet’s corps between Front Royal and Winchester.” To top it off, “they heard that Ewell was establishing a line, so as to draw stores from Maryland and Pennsylvania. Learned from a Confederate soldier, disabled in a house, that A. P. Hill was also in the Valley.” All three Confederate corps were now located and the direction of the movement clarified. His scouts also reported that Ewell’s Corps had concentrated and camped in Boonesboro Valley, in the area of the Antietam battlefield.35

On June 22 Lee ordered Ewell with the rest of his corps, with Hill following directly behind, to cross into Pennsylvania. By the 24th, Sharpe was able to trace a 40-mile column of the Army of Northern Virginia, though the location of particular units remained unclear. A major contributor to this all-source intelligence was the signal system set up only four days before which reported, “Large trains are crossing at Sharpsburg. Artillery and general trains are passing near Charlestown toward Shepardstown.”36 The anxiety level would have risen in the Union army headquarters had they been able to actually witness the enthusiasm with which Lee’s regiments crossed the Potomac, ringing out “Dixie” and “Nellie Gray” as they approached. As the regiments tramped across, their bands burst out with “Dixie.” Major General John Bell Hood would note, “Never before, nor since, have I witnessed such intense enthusiasm as that which prevailed throughout the entire Confederate Army.” Undoubtedly it was helped along by the whiskey ration he issued on the occasion.37

Unfortunately, for Hooker and Sharpe, the level of uncertainty was already high; heavy reporting from other commands dumped a good deal of erroneous information on Hooker, information that was not subject to Sharpe’s all-source processing. A telling part of that information was based on a Confederate deception that had Hill’s men in Maryland pretend to be Longstreet’s men. Hooker thus believed that Lee’s entire army was across the Potomac on the road to Pennsylvania when, in fact, Longstreet’s Corps was still in Virginia. Based on this unverified information, Hooker put his entire army in motion once again. By June 27, the blue columns had completely cleared the Potomac even ahead of the Army of Northern Virginia and began the northward movement to parallel Lee on the other side of the Blue Ridge and South Mountains across the Potomac. Hooker now had stolen a march and got the inside track that would allow the Army of the Potomac to intercept its opponent. It would be a tremendous advantage in the coming crisis; ironically, it was based on bad intelligence, which in turn was based on a Confederate deception that worked far too well. All in all, it was a telling example of the law of unintended consequences in high gear.

Lee was not finished with disinformation. In a series of letters to Jefferson Davis dated June 23 and 25, he elaborated on a plan he had obviously been thinking about for over a month. He urged Davis to assemble a small army under General Beauregard at Culpeper Courthouse to threaten Washington from the south while he threatened it from the north. Shortly after Chancellorsville, Lee had suggested bringing Beauregard to command a new force because “the little Cajun’s” reputation was strong in the North. As early as May 14, one of Sharpe’s agents traveling through Lee’s forces around Culpeper had picked up the rumor which Lee had probably planted. By early June Lee was discussing the plan with Longstreet. That plan called for scouring the Confederate Atlantic coast and Richmond garrisons of their brigades. At that time in the Department of North Carolina, there were six brigades and another body of troops at Cape Fear as well as three cavalry regiments. With these forces and what could be scrapped up in South Carolina, he thought a credible IV Corps could be created that could move on Washington. At the same time, though, he wanted Corse’s Brigade of Pickett’s Division—which had been left in Richmond as part of the garrison—to join him as well as one of the North Carolina brigades (Micah Jenkins’s). He was hopeful that such a force would pull at least one corps if not more from the Army of the Potomac to defend the national capital.38

As the armies crossed into Union territory, Sharpe began to receive a flood of information from his scouts. The length of Lee’s column loosened his hitherto tight security. At this time, Stuart was given an independent mission to cross the Potomac east of the Blue Ridge and keep in contact with Ewell’s right flank. His first problem was that in attempting to cross the Potomac River he had to move further and further east to avoid collision with the mass of Hooker’s army on its movement north. Hooker’s interposing army effectively put him out of range of supporting Ewell. At the same time, Stuart began to turn a flank security mission into another great raid that would reestablish his Brandy Station-tarnished reputation. Stuart had done Sharpe a great service in removing his cavalry from Lee’s flank. Up to this point, Stuart had done a splendid job keeping Union eyes off Lee’s unfolding operation. Stuart was not entirely to blame, as Lee left two of Stuart’s brigades guarding gaps in the Blue Ridge long after his army had passed north.39

Stuart was responsible for selecting Brig. Gen. Beverley Robertson (commanding his own brigade) as the overall commander of both brigades. Longstreet for one had had no confidence in him and wished Brig. Gen. John Imboden assigned this mission. Robertson’s instructions from Stuart, dated June 24, were clear:

Your object will be to watch the enemy; deceive him as to our designs, and harass his rear if you find he is retiring. Be always on the alert; let nothing escape your observation, and miss no opportunity which offers to damage the enemy.

After the enemy has moved beyond your reach, leave sufficient pickets in the mountains, withdraw to the west side of the Shenandoah, place a strong and reliable picket to watch the enemy at Harper’s Ferry, cross the Potomac, and follow the army, keeping on its right and rear.40

These instructions were so clear that, had Robertson executed them with alacrity, Stuart’s subsequent absence at a critical time of the campaign would not have deprived Lee of his eyes and ears. The cavalry he left with Robertson would more have compensated for his absence. In fact, the junior of the two brigade commanders, Brig. Gen. “Grumble” Jones, was considered the finest outpost officer in the Army of Northern Virginia. Instead, Robertson lingered over a week in the quiet mountain passes after both armies had moved on, far too long for the cavalry to play any significant role after they were finally recalled to join Lee.

Lee had a few other intelligence assets with him. In June he had appointed Major John H. Richardson, commander of the 39th Battalion, Virginia Cavalry, of 200 officers and men, to his staff. The battalion’s duties included scouting enemy positions and finding efficient routes in the army’s line of march. At least one company accompanied Lee’s headquarters, with the other companies assigned to each of the three corps headquarters.

The 1st Battalion, Virginia Infantry, of 250 men, was assigned as the army provost guard and marched behind the army, rounding up stragglers and deserters. Lee assigned its commander, Capt. David B. Bridgford, as his acting provost marshal. In addition to its military police duties, the battalion was charged with collection and interrogation of prisoners of war. The battalion was to collect order-of-battle information by collating from prisoners and deserters the “names, regiments, brigades, and corps.” When Lee reached Winchester on June 24, he could not ascertain the whereabouts of the 1st Maryland Battalion with which he had intended to garrison the town. Instead, he left the 1st Virginia Battalion as its garrison. This effectively took his provost guard out of the operation. Thomas J. Ryan comments, “In the absence of his headquarters provost guards, Lee would have to rely on those units at brigade, division, and corps level to interrogate prisoners and acquire order of battle and other intelligence. He thus lacked direct control over the process that would be needed to derive timely intelligence in a combat situation.”41

Lee’s ad hoc provisions for his provost marshal operation are in stark contrast with those of the Army of the Potomac. Lee’s provost marshal was a captain commanding a battalion of 250 men. His Union counterpart, Patrick, was a brigadier general with the equivalent of an infantry brigade—1,787 officers and men—in his provost guard.42

As Lee was blinded by Stuart’s ride around the Army of the Potomac, Sharpe began receiving more and more accurate information. The wires were pouring in reports from 13 separate army and government sources. Even more important was the information from refugees and patriotic citizens, such as those in Chambersburg, Pennsylvania, who set out to gather information even while under occupation. Amazingly, about 75 percent of it proved accurate, which Sharpe’s all-source methodology was able to substantiate. One citizen provided a highly accurate count of Lee’s artillery and an overall strength figure that was also very close to actual strength as of June 27. Other reports located Lee and his subordinate commanders at Chambersburg and marked their departure on the road to Gettysburg. On that same day, Hooker, who had demanded control of the Harper’s Ferry garrison on threat of resignation, got his subliminal wish. Lincoln relieved him.

His replacement was the V Corps commander, Maj. Gen. George Gordon Meade. Lincoln passed over his first choice, Maj. Gen. John Reynolds, because the general had stipulated that he wanted a completely independent command, but he had recommended Meade. When the assistant adjutant general of the army woke him in his tent well before dawn on June 28, Meade thought it was to arrest him, his mind racing over what he had possibly done to merit this. At first he protested that the command should go to Reynolds, his respected senior. But the bearer of his promotion insisted that the president wanted him, and Meade dutifully accepted. It would be a sound choice. This Pennsylvanian was a consummate and reliable professional who had the confidence of the army. He was also a friend to the intelligence effort and a man McClellan rated as “an excellent officer; cool, brave, and intelligent.”43

Unfortunately, Hooker’s habit of keeping his senior commanders in the dark not only on operational matters but also on the coordination of intelligence required Meade to spend a day being intensively briefed by Sharpe. The experience established a mutual self-confidence and certainly removed the load of anxiety Sharpe had been bearing. After the increasingly erratic Hooker, the cool-headed Meade was an enormous relief. Meade immediately put Sharpe’s analysis to good use by fanning the army corps out over a 60-degree angle between Emmitsburg and Westminster in Maryland, with the aim of intercepting at least part of Lee’s army. Information from the Gettysburg group of citizen scouts had identified the march of Early’s Division of Ewell’s Corps through their town and northward. Meade aimed to cut right through it. At this time Babcock and his scouts returned from the Frederick area; Butterfield personally introduced him to Meade and fairly sang his praises and received the compliments of the new commander for the value of his service. Meade, at this time, was welding a team and certainly won Babcock over.44

As Stuart rode east of the Army of the Potomac on June 29, he severed all the telegraph communications with Washington. However, scouts had already reported on that day that the Confederates had marched out of Hagerstown and marched toward Chambersburg, Pennsylvania.45 Loss of the telegraph cut off Sharpe from sources of information in-theater. He was now thrown on his own resources, but Meade was working closely with him and ordered all of the BMI’s scouts out to gather more information. Butterfield’s order to Sharpe read: “The major-general commanding desires that you send to Gettysburg, Hanover, Greenscastle, Chambersburg, and Jefferson to-night and get as much information as you can of the numbers, position, and force of the enemy, with their movements.” Unbeknownst to Meade, that had already been done by Sharpe’s intrepid scouts. Sergeant Cline again had slipped in among the Confederates in Hagerstown and was forwarding valuable information. Another of his scouts, Ed Hopkins, had ridden ahead with the cavalry and entered Gettysburg, where he sought out McConaughy’s group and established liaison with Sharpe. It was a decisive action. Hopkins’s report, which he delivered to Reynolds at Emmitsburg, was amazingly accurate:

… a scout of Sharpe’s, has just returned from Gettysburg, with a statement of affairs in that quarter yesterday. Early’s division passed there in the direction of York, and the other division (Gordon’s, I think), with the trains, was in the Valley, and moved along a road nearer the mountains. Another division (Rodes’) of Ewell’s was up by Carlisle, and Hill (A. P.) was said to be moving up through Greencastle, in the direction of Chambersburg. The cavalry with Early was sent off to Hanover Junction, and up the railroad to York.46

McConaughy’s efforts and those of other citizen groups in Chambersburg were telling Meade the location of Hill’s and Ewell’s Corps. Sharpe had already appreciated the great value of McConaughy’s earlier information as had Meade, who would write in a circular on the first that “All true Union people should be advised to harass and annoy the enemy in every way, to send information, and [be] taught how to do it; giving regiments by number of colors, number of guns, generals names, &c.”47 Sharpe now pressed the Gettysburg agent for more in a letter on the 29th:

The General directs me to thank you for yours of today. You have grasped the information so well in its directness & minuteness, that it is very valuable. I hope our friends understand that in the great game that is now being played, everything in the way of advantage depends upon which side gets the best information. The rebels are shortly in advance of us—but if thro’ the districts they threaten our friends will organize & send us information with the precision you have done, they may rest secure in the result—and we hope a near one. The names of the Generals, the number of the forces, if possible, are very important to us, as they enable us to gauge the reports with exactness.

The General begs, if in your power, that you make such arrangement with intelligent friends in the country beyond you to this effect, and that you continue your attention to us as much as your convenience will permit.

Hoping at some future day to have the pleasure of meeting you, I am, dear sir, yours very truly,

Geo. B. Sharpe

Col. and of Gen’s Staff, Army of the Potomac.48

McConaughy’s reports more than any other source drew Brigadier General John Buford and his cavalry division toward Gettysburg on June 30. Buford was an experienced and aggressive commander with a keen appreciation of the intelligence role of the cavalry. He also firmly believed in the timeliness of information, as his rapid stream of dispatches to higher headquarters showed. His division was guarding the army’s left flank as it moved north. These were the three corps (I, III, XI) under the operational control of the I Corps commander, Maj. Gen. John Reynolds. Reports on the enemy—which was closer to Reynolds and Buford than army headquarters itself—were arriving from Sharpe because they had come directly from McConaughy.

Lee at Chambersburg was oblivious to the flurry of intelligence that was concentrating the Army of the Potomac against him. He fully shared the invincible enthusiasm of his men. He had heard of Meade’s appointment at least by this time and commented to Major General Hood, “Ah! General, the enemy is a long time finding us; if he does not succeed soon, we must go in search of him.”49

It was a reflection of hubris that was about to be quickly answered. By June 29 Buford had reached the village of Fairfield about 5 miles south of Gettysburg where he received an order from Pleasonton, based on Sharpe’s intelligence, directing him to move to Gettysburg by the following night. That very night, while still in Fairfield, his scouts captured a Confederate courier near Oxford with a dispatch from Confederate Major General Early that showed his location and the rest of Ewell’s Corps north of Gettysburg. Buford was especially exercised that he had missed the opportunity to bag two Mississippi regiments camped nearby because of the complete lack of cooperation from the townspeople:

The inhabitants knew of my arrival and the position of the enemy’s camp, yet not one of them gave me a particle of information, nor even mentioned the fact of the enemy’s presence. The whole community seemed stampeded, and afraid to speak, often offering as excuses for not showing some little enterprise, “The rebels will destroy our houses if we tell anything.” Had any one given me timely information, and acted as guide that night, I could have surprised and captured or destroyed this force…50

Happily, the citizens of other towns, such as Chambersburg and Gettysburg, were made of more patriotic stuff.

The last day before the collision of the armies at Gettysburg was June 30, a day when all-source intelligence had already fused a coherent picture of the enemy. Scouts, civilian informants, and the cavalry were all contributing to Meade’s intelligence summary of that day, which he sent to all his corps commanders. “[F] rom present information, Longstreet and Hill are at Chambersburg, partly toward Gettysburg; Ewell at Carlisle and York. Movements indicated a disposition to advance from Chambersburg to Gettysburg.” With this order, he put his corps in motion, directing I and XI Corps to Gettysburg and the others to within supporting distance.51 Meade was also being served by the synergistic effect of the determined initiative and efficiency of his sources, of which, at this point, John Buford would outshine all others.

Buford rode into Gettysburg, arriving at 11 a.m., well ahead of schedule. He was preceded by a detachment of scouts of the 3rd Indiana Cavalry, Hooker’s old Horse Marines, as well as men of the 8th Illinois Cavalry, led by Sgt. Harry B. Sparks of Company C. They charged “into the streets in a full, pounding gallop, surprising and capturing several Confederate stragglers from their earlier expedition into the town four days prior.” Buford arrived to find the town in a state of hysteria generated by the imminent arrival of a Confederate force. It was barely a half-mile away. Buford wrote that the local civilian description of the enemy force “was terribly exaggerated by reasonable and truthful but inexperienced men.” He had no trouble driving the Confederates back toward Cashtown when apparently he made contact with McConaughy. “On pushing him back toward Cashtown, I learned from reliable men that one of Hill’s divisions was marching in this direction heading for York to the east of Gettysburg.” He immediately sent out patrols, one of which found a pass signed by Lee that day putting him at Chambersburg.52

That night, at 10:30 and 10:40, he wrote two highly accurate reports that he sent to Reynolds and Pleasonton who were with Meade at Taneytown. He identified Hill’s Corps at just west of Cashtown with his pickets only 4 miles from Gettysburg. “Longstreet, from all I can learn, is still behind Hill.” Finally, he fixed Ewell’s movements, “Near Heidlersberg today, one of my parties captured a courier of Lee’s. Nothing was found on him. He says Ewell’s corps is crossing the mountains from Carlisle, Rodes’s division being at Petersburg in advance.”53 In effect, he had identified all three of Lee’s corps and their evident movement in the direction of Gettysburg.

That same evening in Emmitsburg, the commanders of I and XI Corps met to discuss the intelligence they had received throughout the day. Major General Howard recalled that the reports “were abundant and conflicting. They came from Headquarters at Taneytown, from Buford at Gettysburg, from scouts, from alarmed citizens, from all directions. They, however, forced the conclusion upon us that Lee’s infantry and artillery in great force were in our neighborhood.”54 Intelligence clearly was pulling the Army of the Potomac to Gettysburg like a magnet. Reynolds would have had a better grasp of the situation because John Babcock and Captain McEntee and a number of his scouts were traveling with the headquarters to provide collection and analysis support.55 That night, Meade ordered the two corps to the little crossroads town in Pennsylvania.