Constantly monitoring her surroundings, Christina inserted her key into the research building at UCLA. Swiftly she drew her bike in behind her, like a sailor entering the pilothouse during a storm. She tugged at the door to hasten its latching. An uneasy quiet lay over the building. The lights and air conditioning were still on, and she saw no sign of vandalism. The elevator opened and she rode it to the Bioenergy Institute floor.

The door to Chen’s laboratory was closed and locked but the lights were on inside. To avoid startling her mentor, Christina first knocked on the door and called out to him before unlocking and entering.

Piles of unwashed glassware and unemptied trash cans testified that much work had been done in the days since she left. She heard sounds in the next room.

“Dr. Chen? It’s Chrissy,” she called and walked toward the sound. “I’m back.”

Robert Chen waved the mouth of a test tube through a Bunsen burner flame, capped it, and set the tube down in a rack. His haggard face lit up when he saw her.

“Chrissy! Hello! Welcome!” he said and gave her a hug. Then his expression clouded. “Is everything okay? Why did you come back?”

“Everything’s fine,” she said, ignoring the obvious complications of life in L.A. at the moment. “I just couldn’t sit at home being useless anymore. I had to come help you.”

“I’d be lying if I said I wasn’t glad to see you. I’ve made progress, tremendous progress, but together we can accomplish twice as much,” he said.

“I see you could use a dish washer. You’re going to run out of flasks.”

Dr. Chen laughed. “I have been going through quite a few bacterial cultures. Did a little research on the nutritional content of bacterial growth media, too. LB broth tastes a bit yeasty but it’ll keep body and soul together in a pinch.”

“You’ve been eating laboratory reagents?” she asked, shocked.

“Only a little, and all of it was sterile.”

She immediately reached into her backpack and handed him a fistful of energy bars. He beamed, tore one open, and ate it on the spot.

“How’s the work going?”

“I may be on to something, Chrissy. A possible cure.”

“Already?”

“A lot of work needs to be done before I can say for certain.”

“What is it?”

“An antibiotic that seems to affect Syntrophus.”

“I thought we tested all the antibiotic classes and none of them worked.”

“This is a new substance. I don’t have a clue what it is, I just know that it’s produced by one of the microbes in our collection.”

“From an oil field?”

“Yes. Presumably these bacteria compete with each other in the wild, and one species evolved to make an antibiotic that kills the other.”

“Like penicillin, which is made by a mold.”

“Right. The good news is, it doesn’t matter whether this chemical is toxic to humans because we won’t be using it as a drug. To use it against the petroplague, we have to identify the substance, and someone will have to find a way to manufacture it in large quantities.”

“But there’s a chance it can be done.”

“Definitely a chance,” Dr. Chen said. He touched Christina’s shoulder. “There’s still hope.”

“Tell me what I can do.”

“Your job is to work on Plan B.”

“Plan B?”

“A million things could go wrong with this antibiotic project. We need a backup plan. Remember your Ph.D. thesis project?”

“The photosynthetic E. coli for Bactofuels.”

“If we can’t beat the petroplague, we’ll have to learn to live with it. Jeff Trinley has been calling me every day to remind me that our E. coli-produced isobutanol could be a very profitable substitute for diesel fuel.”

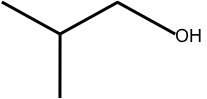

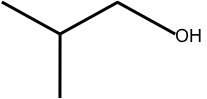

The X-car, Christina remembered. Its internal combustion engine had never run on gasoline. They always fueled it with biodiesel from their experimental E. coli production system. She sketched the structure of the molecule their E. coli produced using energy from the sun.

Isobutanol. Unlike petroleum diesel and gasoline, it wasn’t a hydrocarbon. It was a branched-chain alcohol.

And Syntrophus wouldn’t touch it.

“Trinley’s right,” she said. “The isobutanol will work even in an engine contaminated with Syntrophus bacteria. If it’s the only transportation fuel available, people will pay almost anything for it.”

“Which would solve Bactofuels’ main problem. Before the petroplague, the cost of manufacturing isobutanol using E. coli was much too high to compete with oil.”

“If price is no object, they can scale up the photosynthetic growth tanks.”

“But only if you can get the thermodynamics right,” Dr. Chen said. “We’re still feeding the E. coli sugar to get them to produce fuel. You must wean them off the glucose and make them rely only on the sun.”

This was a formidable scientific task, but she was undaunted. She plotted experiments, and while her ideas took shape, she pulled on some rubber gloves and washed the dishes.