HOW SKEWED IS THE SENATE?

Republicans have held the Senate’s majority for eighteen of the last twenty-six years, leaving only six for Democrats and two when there was a tie. This disparity is likely to continue. Or will so long as Republicans can count on smaller states, with their two seats, regardless of population.1

As we are constantly reminded, California’s 39,747,267 residents and Wyoming’s 585,501 both get two senators. This gives Laramie householders sixty-seven times more say in the Senate than those in Santa Rosa.

The Senate wasn’t meant to represent actual people. The framers made clear it was there to safeguard the states, on the premise they all had equal status. Since its structure is embedded in Article I, there’s little chance it will be changed. One recourse is to spell out how far that chamber departs from a popular template.

Due to an interplay of ideology, history, and happenstance, Republicans tend to do better in less settled and more rural states. So the twenty-five smallest states command half the chamber’s seats, despite having only 17 percent of the nation’s population. And in this smaller half, twenty-nine are Republicans against twenty-one Democrats. That eight-seat edge can be decisive on Senate roll calls. Viewed the other way, the twenty-five largest states, which house 83 percent of Americans, have a closer ratio of twenty-six Democrats and twenty-four Republicans. In a word, the two-seats system doesn’t give the Democrats a comparable bonus.

As was noted, Republicans have had three times the odds of ending with most of the Senate’s seats, which means that they are more likely to prevail when rolls are called. Hence this question: when Republicans win on the floor, how many people out in the country are behind those tallies?

In fact, there’s no settled way of calibrating the Senate’s human constituencies. As was seen in the previous chapter, parsing the House of Representatives is easy. In November 2018, Democratic candidates won 54 percent of the major parties’ votes. Even with contorted maps and suppressive schemes, their party ended with 54 percent of the seats. A perfect fit.

Deconstructing the Senate is harder. One approach might be to assign each senator half of his or her state’s population. Since Ohio has a Democrat and a Republican, both would be seen as having a half-state base of 5,859,284. A problem is that this figure includes everyone inside Ohio’s borders, even babies and noncitizens. It also includes everyone who voted against these two incumbents.

Another method is to find how many votes each of them received. Ohio’s Rob Portman won reelection in 2016 with 3,118,567, while Sherrod Brown kept his seat in 2018 with 2,355,923. Does this mean that Portman has more of a mandate? Perhaps. But his higher figure was less a testament to him than because he ran in a presidential year, when turnouts are always higher. Also, there are 1,996,908 Democrats who turned out in 2016 and 2,053,963 Republicans who did in 2018, but who aren’t counted because they voted for the losing candidates. Are senators supposed to represent only the victors?

The best, albeit imperfect, way is to add up the votes cast on each party’s line in all the relevant Senate elections. After all, citizens who voted for losing candidates also wanted to record how they felt. So as the current Senate has one hundred members, we’ll include all votes for all two hundred contenders for those seats.

(Independents like Bernie Sanders are counted as Democrats because they caucus with that party. Other minor parties are not included in the totals because none of their candidates have ever won a Senate seat.)

Here’s a number you are unlikely to have seen, since as far as I know, it hasn’t been compiled before: 218,552,126. It is how many ballots were cast in three cycles—2014, 2016, 2018—in the contests that decided the current makeup of the Senate. The total divides into 121,971,401 (or 56 percent) for the Democrats, and 96,580,725 (or 44 percent) for Republicans. One bottom line is that the Republicans obtained their current majority of fifty-three seats with a minority 44 percent of the votes cast in Senate contests. Here is how these ratios played out when important chips were down.

• In April 2017, the Senate confirmed Neil Gorsuch by a fifty-four-vote majority, from fifty-one Republicans and three Democrats. (One Republican didn’t vote.) The fifty-four senators who elevated Gorsuch represented 46 percent of the electorate that gave them their seats.

• In December 2017, the Senate rushed through a regressive tax bill with fifty-one Republican votes. (One opposed it.) Those fifty-one represented 45 percent of the voting public.

• In October 2017, the Senate confirmed Brett Kavanaugh by a 50–48 margin. That majority had forty-nine Republicans and one Democrat, with two Republicans not voting. The fifty who anointed Kavanaugh represented 46 percent of the active electorate.

For the record, opposition to both Gorsuch and Kavanaugh came in at 54 percent, measured by the vote-base of senators who contested their confirmations. By the same gauge, 55 percent of voting Americans disapproved of the tax bill.

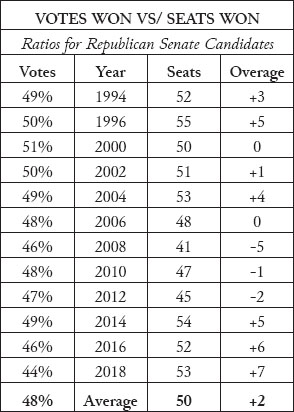

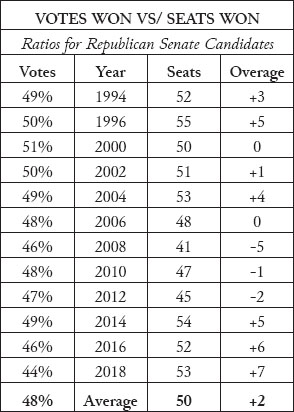

Nor is this an anomaly. I‘ve added votes-to-seats quotients for all twelve Senates, going back to 1994. Altogether, there were some four hundred races, including special elections, as when Al Franken was replaced.

As the table below shows, in four of the twelve years (2000, 2002, 2006, 2010), seats won basically paralleled the electoral results. Among the other eight, Republicans had more seats than their votes would warrant—I call this “overage”—in six of the sessions, leaving Democrats just one. (I’ll be returning to that one.)

Moreover, the overage has grown very visibly in the three most recent Senates, notwithstanding the Democrats’ popular sweep in 2018.

In sum, Article I favors Republicans. Since they carry more smaller states, they win their pairs of seats with fewer votes. Even when Democrats take 53 percent of the Senate’s popular count, they cannot control the chamber.

As matters stand, the only recourse for Democrats is a presidential triumph. The best model was 2008. (Prior to that, one must go back to 1964.) In Barack Obama’s first bid, he routed John McCain by 9,550,176 votes, three times Hillary Clinton’s edge.

His coattails helped Democrats win Senate seats in purple states like Colorado and North Carolina, in both cases by a comfortable 53 percent. More striking were Senate victories in South Dakota (62 percent), West Virginia (64 percent), Iowa (68 percent), Montana (73 percent), even Arkansas (80 percent). The party began 2009 with fifty-nine Senate seats. It had much the same margin in the House of Representatives.

As it happens, the states that had Senate contests in 2008 will be up again in 2020. This time, though, the focus is on Republican incumbents. At least four of them will have to be defeated if Democrats are to control both chambers on Capitol Hill. The final table in this chapter lists six states that belong in the competitive column. Here, as in earlier analyses, the emphasis will be on party commitment, gauged by off-year turnouts. As can be seen, Democrats were more likely to take the time and trouble in all six of the states, with their readiness well ahead in four of them.

| COMPETITIVE SENATE STATES | ||

| 2018 Turnouts Relative to 2016 | ||

| Democrats | Republicans | |

| 96% | Maine | 75% |

| 102% | Iowa | 76% |

| 60% | Colorado | 43% |

| 102% | Arizona | 91% |

| 97% | Georgia | 95% |

| 75% | North Carolina | 72% |