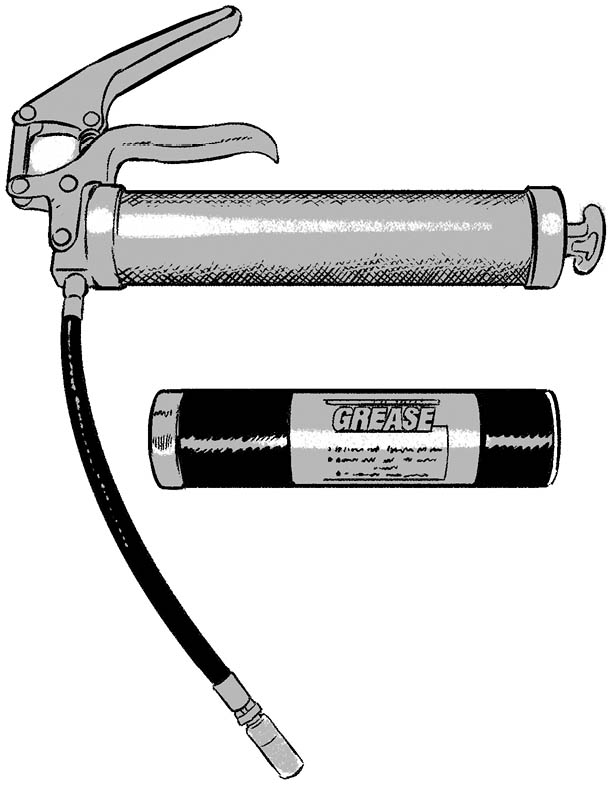

A loaded grease gun with a flexible nozzle is the most important tool on a daily basis for keeping equipment running.

Fluids are critical to keeping parts moving and systems functioning, and are the primary focus of a maintenance program. Engines require fluids in the form of fuel and air to operate. Both engines and implements require fluid lubricants — grease, lubricating oil, engine oil, and gearbox oil (transmission fluid) — to prevent unnecessary wear and breakdowns. Large engines additionally use coolant and hydraulic fluid. There is also a variety of fluid aids and additives for machinery and engines, used to protect or clean different systems.

Most moving mechanical (non-engine) parts rely on grease for lubrication: a combination of oil, soap, and additives formulated to work through a wide range of temperatures and loads. There are hundreds of kinds of grease available, but the only kind needed on most farms is any brand of multipurpose, or MP, grease, either lithium or petroleum based. Still, check your manual to see if a different type of grease is recommended for a particular piece of equipment or a particular mechanism. Tubes of grease are available at any farm store, and grease is applied with a grease gun through zerks, or wiped onto parts with a finger or paper towel.

A loaded grease gun with a flexible nozzle is the most important tool on a daily basis for keeping equipment running.

Lubricating oil is used on parts, such as chains, that need less bulk and more fluidity in their lubrication than grease offers. It also acts as a rust preventive; so that keeping a light coating of oil on nuts and bolts helps ensure that when you need to unbolt things they will come apart easily. Do not use oil on belts, which depend on friction to operate. Use a light oil, such as WD-40, on chains and more delicate mechanisms. On heavy-duty parts exposed to the elements, heavier oil is better; you can even recycle old engine oil for this purpose.

If you’re often running equipment in very dry and dusty conditions, or on very sandy soil, use a dry lubricant such as graphite or dissolved paraffin wax (White Lightning is one brand) instead of oil on chains, to keep grit from sticking to and wearing the chain. For nonmoving parts that must be absolutely dry to function properly, such as the seed bins on planters and drills, use a dry lubricant or a light coat of spray-on metal paint as a rust preventive. When bolts are frozen in place, a penetrating oil such as Liquid Wrench can be applied to help free them.

Most engines have a dipstick attached to the oil fill tube cap for checking the engine oil level, but some small engines instead use a check plug. Instead of checking the height of the oil film on a dipstick, you unscrew the check plug to see if oil flows out. If it doesn’t, the level is low. Check plugs are also commonly used to monitor fluid levels in hydraulic systems and gearboxes.

Engine oil level is checked either with a dipstick or a check plug. Hydraulic fluid and gearbox oil are most often checked with a check plug.

Every engine is engineered to run best with a specific “weight” of oil, so check the manual to see what’s recommended, and use that. Oil weight is indicated by the numbers and letters on the bottle, which refer to viscosity — weight is the common term for viscosity — and quality. Viscosity is the measure of the thickness, or flow rate, of the oil. Lower numbers signify thinner oil; higher numbers mean thicker.

Thin oils work well in low temperatures or under light loads; thicker oils are necessary for high temperatures and heavy loads. Small gas engines work at high temperatures and full loads and generally require oil in the SAE 30 range (SAE stands for Society of Automotive Engineers, which sets viscosity standards). Cars, tractors, and other machines with large engines that are operated through a wide range of loads and temperatures do better with multiple-viscosity oil. This type of oil has two numbers on the bottle, such as 10W–30, and contains additives that make it thin at lower temperatures and thicker at higher temperatures. In this example, the W means this oil is appropriate for winter use, the 10 is its viscosity when cold, and the 30 its viscosity when the oil is warm.

Oil quality, or service rating, is indicated by the letters on the bottle. This rates the engine-protecting quality of the oil, indicating the presence of additives to prevent rust and corrosion; reduce heat, soot, and carbon left over from combustion; seal compression; and dampen vibration. All categories but SH and SJ are now considered obsolete; either of those two is fine for farm engines. A C instead of an S means the oil was formulated for diesel engines.

Finally, synthetic oil can be substituted for the same weight of petroleum-based oil. Though it’s more expensive, it may make engines easier to start in the winter and retain its protective and lubricating qualities for a longer time.

Because fluids can seep through small seams between parts, gaskets — rubber, paper, cork, or soft metal — are often used in fuel, oil, and hydraulic systems to tightly seal connections between parts. Gaskets are replaced if they’re leaking, or if they’re exposed by disassembly.

Oil, fuel, coolant, and other fluids can be a hazard to plants, animals, and groundwater if allowed to seep into the ground or poured down a drain. Always put old fluids in covered buckets for proper disposal. Old oil and hydraulic fluid can be dropped off at a hazardous fluids collection site in your area, or you may find an auto or engine repair shop with an oil-burning heater that will be happy to take the stuff off your hands. Antifreeze (sweet tasting and poisonous to animals and children) and other fluids should be turned in at hazardous waste collection sites.

Spills (and we all have them) can be covered with kitty litter or shop rags or even dirt to absorb the liquid, then scooped up and bagged until it can be properly disposed of.

The octane rating of gasoline should be appropriate for the engine. In cars, a high-octane gas allows for higher compression before combustion, delivering more power and less of the preignition that causes engine knocking. In a small engine, though, many mechanics say that a high-octane fuel will burn the valves and pistons and ruin the spark plugs. Fuels containing ethanol or alcohol also burn hotter and may have the same effect.

On the other hand, some mechanics and owners say that high-octane fuel gives better performance. See what your manual recommends for a particular engine, or try both types of fuel to see what works best for your equipment. We use 87-octane regular gasoline with 10 percent ethanol.

In old tractors with engines built to use leaded gasoline, add lead replacer each time you gas up. This costs just a few dollars a bottle at any farm store and protects the valve seats from rapid wear. Adding more than the recommended amount per gallon won’t hurt, so don’t skimp. If your tractor was built after 1975 or has had an engine rebuild, it probably has hardened valve parts, so lead replacer isn’t necessary.

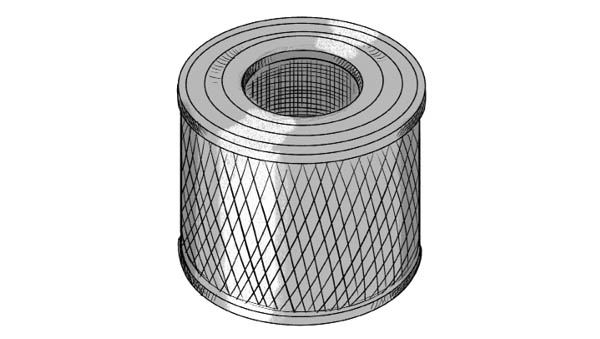

Fluids must be free of contaminants for optimal engine performance. Small engines have air filters and fuel screens for this purpose; large engines have air and fuel filters, plus oil and hydraulic filters. These should be cleaned or changed as directed in the owner’s manual.

Air filters come in all sizes and shapes to fit the variety of engines found on most small farms. They’re cheap and simple to replace on small engines; on tractors, you may have to disassemble and clean them once a year.

Larger tractors generally are designed to use diesel fuel instead of gas. Diesel will thicken and gel at low temperatures; if you plan to use that engine during the winter, use a winter diesel blend if available, and store the machine in a heated shed, or install a plug-in block heater on the engine.

When storing gas engines for long periods, add a gas stabilizer to the tank. This prevents gumminess, which can make the needle valve on the carburetor float bowl stick so the engine won’t start. After you’ve added stabilizer (we use Sta-Bil), run the engine for 5 to 10 minutes so the additive has time to work its way through the carburetor. Then top off the gas tank; this keeps water from condensing in the tank and fuel line as the engine cools, another frequent cause of engine problems.

Without air, fuel will not ignite; up to 9,000 gallons of air are needed to burn a gallon of gas. If the air is full of dust and grit, this will scratch and abrade the combustion chambers and work its way into the rest of the engine to cause more wear. For this reason, air intakes on all engines are equipped with some type of filter. Air also carries away the by-products of combustion through the exhaust system.

Bigger engines, like those on tractors, need more cooling than is provided by air movement, and so utilize liquid cooling systems. A mix of one-half antifreeze and one-half distilled water is the standard coolant formula; to maintain the right ratio you can premix the two and store in labeled jugs. Coolant is circulated around the engine to absorb and carry off excess heat to the finned radiator.

Using tap water rather than distilled water is okay, but you’ll get more deposits and corrosion in the radiator core. If you dilute the antifreeze with too much water, the coolant is more likely to freeze in cold weather and boil over at high temperatures. Lastly, never remove a radiator cap until the engine has cooled off, and don’t add cold coolant to an overheated engine, since this can crack the block.

Note that antifreeze is highly toxic and sweet tasting to animals; spills should be immediately wiped up, or, if your shed has a dirt floor, scoop up the contaminated dirt and dispose of it where no animal can find it.

Gearboxes are lubricated by heavyweight transmission oil, and no substitutes should be made for the weight specified by the owner’s manual. Large engines may also use power steering fluid and brake fluid to operate those mechanisms, and though engine oil may be substituted in an emergency, the system should be repaired and refilled with the correct fluid as soon as possible.

A hydraulic system works by pushing noncompressible liquid through hoses, fittings, and hydraulic cylinders to lift or swing an implement or attachment. Use only hydraulic fluid in a hydraulic system, although in cold weather in small systems (such as a hydraulic wood splitter), lighter automatic transmission fluid can be substituted, for easier starting.

Fluid aids for engines include lead replacer for old tractors, fuel additives to clean carburetors, and flushes for radiators and crankcases (the lower part of the engine block where the crankshaft is located). Another type of additive promises to plug radiator leaks; this is not recommended by most manuals since it may also clog the smallest channels in the radiator, and it is only a temporary fix.

Aids for non-engine parts include penetrating oils to free frozen bolts; adhesive coatings (such as Loctite) to keep bolts from vibrating loose; and degreasing solvents such as mineral spirits, kerosene, and the like (don’t use gas — it’s too flammable), for cleaning such things as seed tubes, and to remove gummy deposits. Some spray solvents for carburetor and brake drum cleaning have more aggressive solvents, such as toluene or acetone, which can be hard on plastics and paints.

Even small farm operations can wind up with many engines and implements, each with its own capacities and requirements for oil, fuel, and other fluids, as well as belt sizes and tire pressures. Listing this information on a single page and hanging it next to the tool bench is much quicker than paging through owner’s manuals for the information whenever you want to change oil or do other maintenance. Also helpful is keeping a diary of what maintenance and/or repairs were done on what date to which machine (see this example of a Maintenance Log).