And yet I am, and live—like vapours tost

Into the nothingness of scorn and noise,

Into the living sea of waking dreams,

Where there is neither sense of life or joys

—John Clare, “I Am”

Part of human interpretation in psychiatry is trying to get an idea of what a person’s disorder feels like from inside. Psychiatry textbooks and the flat prose of papers in journals can leave medical students unprepared for bizarre things they might encounter on a psychiatric ward. Even if all my conjectures were to turn out correct, what I’ve said so far about delusions would not do much to convey the feel of having a delusion. First-person accounts give a better idea. But people with psychiatric disorders sometimes find their inner world hard to express in words. Their art may get closer to conveying their experiences.

Here I will refer to a few paintings and drawings to illustrate certain common patterns, as well as the great variety of psychiatrically disturbed experience. This art does not have to be reducible to mere medical symptoms. It can be powerful as art, making vivid some experiences that are otherwise inaccessible. It can express totally sane moral or political responses to the person’s situation. Some major artists who have had psychiatric disorders have been able to turn this experience into a positive contribution to their art. William Blake and Vincent van Gogh, for example, put to creative use disorders few or none of us would choose to have.

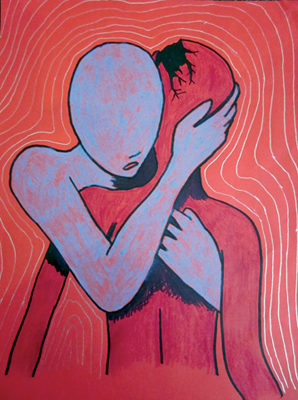

Sometimes people with psychiatric problems paint pictures that portray the living sea of waking dreams with such force and directness that no interpretation is needed. Laura Freeman, a university student with mental health problems, has a blog “How to Juggle Glass” reflecting this experience. Some of her paintings, such as the one shown in Figure 13.1, have an immediate emotional impact. Another of hers conveys more powerfully than words the disruption, darkness, and isolation of a state of depression (Figure 13.2). The forcefulness of these pictures dramatically reduces the “gulf that defies description.” The directness is linked to being clearheaded about a psychiatric problem, with no self-deception or “lack of insight.”

Figure 13.1: Laura Freeman, Broken Hug. Courtesy of Laura Freeman.

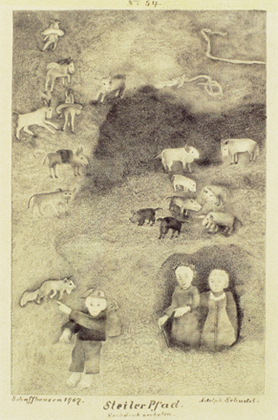

Not all psychiatric art communicates self-awareness of such clarity. Some paintings and drawings convey vividly but less directly the ways in which psychiatric disorder affects people’s feelings and how they see things. These can have a disturbing strangeness, giving only enigmatic clues to their inner lives. Figure 13.3 shows a painting by Adolf Wölfli. The painting is powerful, but we might wonder how much self-awareness Wölfli had about the strangeness of the experience it expresses. The little bits of writing included in Wölfli’s painting are one clue to its “psychiatric” origin. A lot of art reflecting psychiatric problems is filled much more with obsessive, tiny writing. This painting is mainly disturbing because of its pattern and “relentlessness.” It is symmetrical, precise, and detailed. There is an insistent rigidity, with no asymmetry allowing the eye to wander to any other focus. The picture seems to force itself on us, as Wölfli’s experiences may have forced themselves on him.

Figure 13.2: Laura Freeman, Hiding in the Dark. Courtesy of Laura Freeman.

In Heidelberg, a small collection of paintings and drawings made by psychiatric patients, probably started by Emil Kraepelin, was greatly expanded by Dr. Hans Prinzhorn. He published his book Artistry of the Mentally Ill, based on these pictures, in 1922.1 The collection is the great source for psychiatric art in Europe from the late nineteenth century to the first quarter of the twentieth century. The year after Prinzhorn published his book, Max Ernst showed it to artists in Paris. In the 1940s Jean Dubuffet collected paintings of psychiatric inpatients under the title of L’Art Brut (Raw Art). Through these and other channels psychiatric art influenced much other painting. Because of this, some slightly later work is perhaps too self-consciously aware of what it “should” look like. The Prinzhorn artists may have been more innocent in expressing their experiences.

Figure 13.3: Adolf Wölfli, Angel, 1920. The Anthony Petullo Collection.

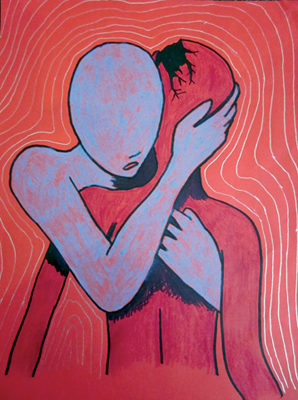

Sometimes the content simply depicts delusions already described in words. Jakob Mohr was paranoid. He described how transmitted electric waves turn him into a “hypnotic slave.” His drawing shown in Figure 13.4 is a diagram showing this influence by the arrows going toward him. (There is again the obsessiveness conveyed by the voluminous amount of minutely written text in his drawing.) The controller of the machine also extracts Mohr’s thoughts and listens to them through headphones: “Waves are pulled out of me through the positive electrical attraction of the organic positive pole as the remote hypnotizer through the earth.”2 The diagrammatic detail in the drawing, titled “Proofs,” may be meant to persuade others that the delusion is true.

Figure 13.4: Jakob Mohr, Proofs. Copyright © Prinzhorn Collection, University Hospital, Heidelberg.

Figure 13.5: Else Blankenhorn, Untitled. Copyright © Prinzhorn Collection, University Hospital, Heidelberg.

There are recurring patterns in the work in the Prinzhorn collection, but individual artists’ experience is not submerged in a collective “psychiatric” style. At the other extreme of style from Mohr, some of the work has little detail and few clear boundaries. A weirdly ethereal atmosphere is created, as in the painting by Elsa Blankenhorn of a woman surrounded by a halo of cloud perhaps blurring her view of others and their view of her (Figure 13.5).

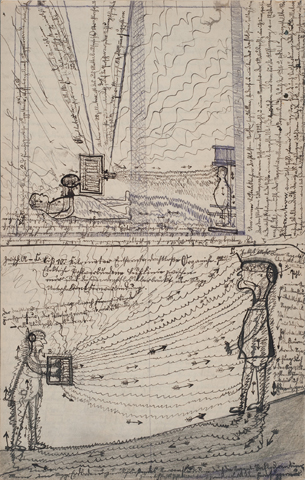

Many other works give a vivid impression of artists’ inner states. The drawing in Figure 13.6 was by Adolf Schudel, whose diagnosis was “hallucinatory insanity.” Dr. Prinzhorn seems to have found it baffling: “The picture has a strange and eerie quality because of the strangeness of the details and because we find it impossible to attribute any rational meaning to it. It crumbles into numerous single motifs, each of which seems to want to say something original without finding the saving expression. For whom is the pointing gesture of the pale dwarf intended—for the viewer or for the two women emerging from the cave? We gain nothing by posing such questions; the decisive element of this magic world lies precisely in its ambiguous impression, and its relative cohesion can be explained convincingly neither by the composition nor by any rational relationship between the figures.”3

Figure 13.6: Adolf Schudel, Steep Path. Copyright © Prinzhorn Collection, University Hospital, Heidelberg.

Perhaps the bafflement stems from looking for an interpretation at too detailed a level—at the “single motifs” and at the relationship between the figures. Seen less analytically, but as a whole, it seems a powerful expression of Adolf Schudel’s inner world. Two women emerge from some dark hole or tunnel, only to be pointed toward a steep upward path already possessed by strange and frightening animals, beyond which are snakes. Anyone seeing their own life like this has reason to despair, or at least to feel terribly daunted.

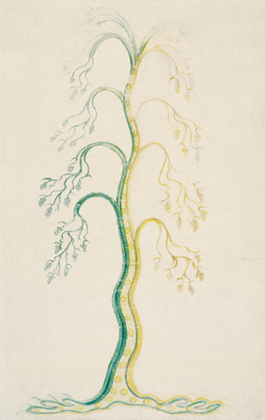

Figure 13.7: Heinrich Anton Mueller, A Proud Earthly Tree With Little Bunches. Copyright © Prinzhorn Collection, University Hospital, Heidelberg.

Figure 13.8: Aloise Corbaz, Palais Rumine. From the Musgrave Kinley Outsider Collection, The Whitworth Art Gallery, The University of Manchester.

Others express an inner world more obliquely, by showing physical objects seen differently. Curves in things normally straight, as in the tree depicted in chalk by Heinrich Anton Mueller (Figure 13.7), give an impression of a world in which firm objects become droopy and might just slither away.

Aloise Corbaz was diagnosed with schizophrenia. Her painting shown in Figure 13.8 powerfully reflects the strange and disturbing inner world of her disorder. There is the bright purple dress, which somehow flows into her breasts—not flowing into covering them, but into being them. It is the same with her arms and hands. The face is shaped like a stylized heart or shield. Do the strange, opaque blue eyes (or glasses?) suggest a barrier stopping the woman from seeing the world or a barrier preventing us from seeing inside her? Or both? On the left at the bottom of the purple dress is what looks like a pair of feet, of which only the toes can be seen. Looked at another way, these can be seen as the claws of a vulture-like bird, a view that turns the purple arms above into flapping wings. On the right at the bottom is another pair of feet with toes or claws apparently attached to the same purple “body,” which suggests that the woman’s head might be the front of a four-legged animal. Apart from the board at the bottom saying “Palais Rumine,” the picture is all flowing curves with no straight lines or square angles, which echoes Heinrich Mueller’s tree painting in creating the impression of a kind of permanent slithery motion.

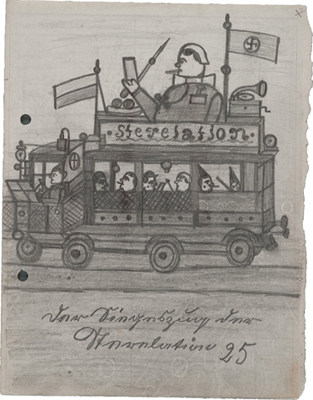

Figure 13.9: Wilhelm Werner, Sterilization Bus. Copyright © Prinzhorn Collection, University Hospital, Heidelberg.

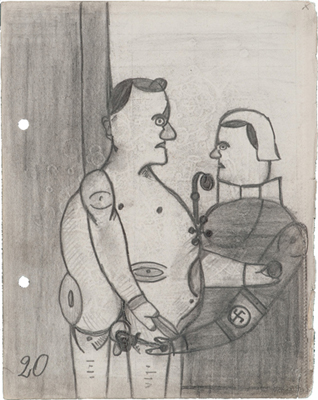

Figure 13.10: Wilhelm Werner, Forced Sterilization. Copyright © Prinzhorn Collection, University Hospital, Heidelberg.

Some “psychiatric” art is powerful in another way. Wilhelm Werner was a victim of the Nazis twice over. First the Nazis sterilized him against his will, and then in 1940, as part of the “euthanasia” program, they murdered him. His pictures on the theme of sterilization bring out the grim reality that contrasted with the cheery Nazi slogans fed to the public. Figure 13.9 shows a sterilization bus, with partying people inside, a Nazi flag flying, a gramophone playing music, and a nurse atop the bus holding a needle and a plate on which are two testicles.

Werner’s portrayal of himself in Figure 13.10 has some of the characteristic marks of art reflecting inner disturbance. The joints of his body seem to be held in place by the heads of metal bolts. And his hands have metal pincers instead of fingers. But these “psychiatric” aspects of the picture do not in the least diminish the emotional and political power of his depiction of the steely Nazi nurse as she forces the sterilization on him.

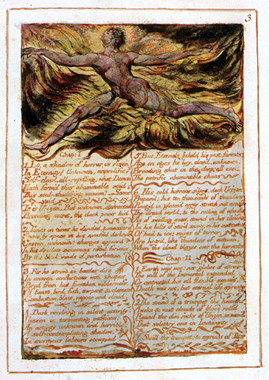

Figure 13.11: William Blake, First book of Urizen, plate 3. Lessing J. Rosenwald Collection, Library of Congress. Copyright © 2014 William Blake Archive. Used with permission.

Few would now doubt that William Blake was one of the most creative and interesting English painters and poets of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. But it is also hard to doubt that nowadays he would qualify for a psychiatric diagnosis. This might be encouraged by the “mad” side of his work. One way in which this comes out is in the look of some of his work and the suggestion it can convey of a private world. His Prophetic Books include many pages of minute writing, like that in Jakob Mohr’s “Proofs” (see Figure 13.4), though Blake’s calligraphy is much more beautiful. A casual glance at some of the many pages of voluminous writing about the bizarre world of Urizen, Los, and others can deter further investigation (Figure 13.11).

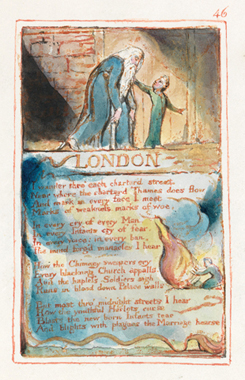

Figure 13.12: William Blake, “London,” from Songs of Innocence and Experience. Copyright © The Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge, UK.

But Blake transcends all this. In Songs of Experience he expresses with anger an utterly sane vision of commercial London’s indifference to victims like the soldier or the child prostitute (Figure 13.12). “Mind-forged manacles” are something close to a human universal, but they had to wait until Blake to be caught in this perfect phrase.

If Blake were alive now, another ground for psychiatric diagnosis would be his apparently psychotic experiences. He describes a complex and self-enclosed religious private world of quasi-biblical mythological people. Is this a ramified delusional system such that—as with Schreber—he literally thinks he is describing reality? Other interpretations might be that this is a consciously created fictional world like that of Tolkien, or that on the “belief spectrum” it lies somewhere between full belief and conscious invention. But the “visions” seem to have been at the “fully believed” end of the spectrum. He had no doubts about his many visions in the garden of his cottage in Felpham:

For when Los joined with me he took me in his firy whirlwind

My Vegetated portion was hurried from Lambeths shades

He set me down in Felphams Vale & prepard a beautiful

Cottage for me that in three years I might write all these Visions

To display Nature’s cruel holiness: the deceits of Natural Religion.

Walking in my cottage garden, sudden I beheld

The virgin Ololon and addressed her as a Daughter of Beulah …

In the catalog to his 1809 exhibition in Soho, Blake says that some of his paintings of the ancient world are copies of originals now lost. “The Artist having been taken in vision into the ancient republics, monarchies and patriarchates of Asia, has seen those wonderful originals … which were sculptured and painted on walls of Temples, Towers, Cities, Palaces … Those wonderful originals seen in my visions, were some of them one hundred feet in height.”4

The journalist Henry Crabb Robinson reports him again speaking of his paintings as simply recording what he saw in his visions: “And when he said my visions, it was in the ordinary unemphatic tone in which we speak of trivial matters that everyone understands and cares nothing about. In the same tone he said repeatedly the ‘Spirit told me.’ I took occasion to say ‘You use the same word as Socrates used. What resemblance do you suppose there is between your Spirit and the Spirit of Socrates?’ ‘The same as between our countenances.’ He paused and added, ‘I was Socrates.’ And then as if correcting himself, ‘A sort of brother, I must have had conversations with him. So I had with Jesus Christ. I have an obscure recollection of having been with both of them.’ ”5

These delusive “visions” about conversations with Christ and Socrates are not easy to separate from the human and moral vision that gives his work much of the power that still resonates. Some of Blake’s contemporaries saw this duality in him. After reading Songs of Innocence and Experience, Wordsworth said, “There is no doubt that this poor man was mad, but there is something in the madness of this man which interests me more than the sanity of Lord Byron or Walter Scott!”6 Henry Crabb Robinson wrote of “the wild and strange, strange rhapsodies uttered by this insane man of genius” and asked, “Shall I call him Artist or Genius—or Mystic or Madman? Probably he is all.”

Would Blake have had his human vision without his “visions”? We find it easy to warm to the vision while rejecting the “visions.” But about Blake himself the question is impossible to answer with any certainty.

The issue is more general, going beyond Blake’s visions to false beliefs in general. Those who are religious believers may seem, to those of us who are not, to be deluded. (Not in the psychiatric sense, but in the minimal sense of holding beliefs that are either false or at least not based on reliable means of tracking reality.) For those of us who are unbelievers, the question about Blake is paralleled by a question about the frequent goodness of character and action found among believers. These include the Quaker pacifists who have borne such impressive witness against war, Archbishop Tutu’s commitment to reconciliation with former oppressors, and Pastor Trocmé’s risking his life in leading his whole village in Nazi-occupied France to hide and shelter hundreds of Jews. It is possible that these good people, even without their religion, would have acted in the same way out of concern or respect for others. But surely it is not obvious that stripping away the religious basis would have left their character and actions unchanged. (Those who think unbelief mistaken—a negative delusion—have the parallel question about moral goodness linked to secular outlooks.)

Blake’s visions seem so central to his whole outlook. They gave him what he saw as a secure basis for an independent religion of his own: a personal standpoint from which to criticize the scientific and philosophical movements of his day and the institutionalized churches.

Perhaps because of a heightened sense of reality they brought, the visions presented themselves to him as indubitable. In this way they provided a fixed point around which his system of beliefs was shaped. This shaping gave him idiosyncratic views about plausibility, which made more straightforwardly empirical views seem distorting and limited. In The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, he wrote: “If the doors of perception were cleansed every thing would appear to man as it is, infinite— / For man has closed himself up, till he sees all things thro’ narrow chinks of his cavern.” Newton, Locke, Voltaire, and Rousseau were among those he thought had closed themselves up, seeing only through the narrow chinks. Their conceptions of the senses were too limited to include visions like his as a source of knowledge.

This highly personal epistemology parallels his confidently personal view of how the dead and formulaic religious morality of the churches drew attention away from the suffering that really mattered. The little boy, in whose voice Blake wrote the poem “The Chimney Sweeper,” who is “crying weep, weep, in notes of woe!,” says his father and mother are both gone up to the church to pray: “And because I am happy, & dance & sing, / They think they have done me no injury: / And are gone to praise God & his Priest & King / Who make up a heaven of our misery.”

Some modern psychiatrists think the problem with hearing “voices” is not the experiences themselves but how people cope with them. There are strategies to help reduce the disruption caused by “voices”: the encouragement of self-help groups, anxiety management techniques, advice to focus on the experiences and to monitor them, to keep diaries and to engage in dialogue with the voices.7 These strategies are claimed to help people to cope successfully with “voices” by integrating them into their lives. (In the case of horrible voices, surely this would be only a second-best strategy, for use only when they cannot be eliminated?)

Blake’s integration of his “visions” into his life can be seen as an unconscious parallel to this. As his visions were benevolent rather than hostile, and he thought they were not delusions, he needed no conscious coping strategy. But the role they played in supporting his highly independent view of the world beneficially integrated them into who he was. They gave him the feeling of solid ground. And this sense of solid ground is apparent in the confidence he always displayed in the vision whose expression was the heart of his life.

The fame of Vincent van Gogh’s “madness”—unlike that of his paintings—exaggerates the reality.

Dr. Peyron, the doctor at the asylum, diagnosed epilepsy, though that hardly seems to cover the range of “psychiatric” symptoms described by those who knew him and by van Gogh himself. Karl Jaspers thought the diagnosis should have been schizophrenia.8 But Kay Redfield Jamison, citing the family history of severe mood instability, more plausibly suggests manic depression. She points out that in nineteenth-century France the distinction between that and epilepsy was not clear.9

There are obvious problems in “diagnosing” people long dead. But there is no doubt that van Gogh had a major psychiatric problem. He had recurring depressions. In his first breakdown in 1888 he threatened Gauguin with a knife, which he then used to cut off his own ear. After this and after other breakdowns he spent periods in the asylum. At these times he heard voices and, as others told him, “it seems that I gather dirt and eat it.”10 Those around him wrote to his brother expressing acute concern. In December 1888 one wrote, “I think he is lost. Not only is his mind affected, but also he is very weak and despondent.” Two months later another wrote, “He has imagined that he is being poisoned and is seeing nothing but poisoners and poisoned people everywhere.” He became mute and hid under the bedcovers, sometimes crying.

With all this, is it really plausible to say that the legend of his madness exaggerates the reality? These acute outbreaks of violence and paranoia were self-contained psychotic episodes. In the rest of his life he was clearheaded about them. His reaction was the opposite of Blake’s endorsement of his own visions. In what Karl Jaspers called “his sovereign attitude towards his illness,” van Gogh saw it as something to reject, to escape from by creative work: “It is perfectly true that last year the attack returned various times—but then also it was precisely by working that my normal condition returned little by little. It will probably be the same this time.”11

A month later he wrote about part of his vision of his own work, and again about its role in resisting his illness: “Aurier’s article would encourage me, if I dared let myself go, to risk making a kind of tonal music with colour … But the truth is so dear to me, trying to create something true also, anyway I think, I think I still prefer to be a shoemaker than to be a musician, with colours. In any event, trying to remain true is perhaps a remedy to combat the illness that still continues to worry me.”12 And three months after this he wrote, “At the moment the improvement is continuing, the whole horrible crisis has disappeared like a thunderstorm, and I’m working here with calm, unremitting ardour to give a last stroke of the brush.”13

The letters also sometimes have a down-to-earth sanity that includes a good ear for the apt mocking phrase, whether used to puncture things overrated or applied to himself. He praises a character in Daudet for saying that, “achieving FAME is like when smoking, sticking your cigar in your mouth by the lighted end.” And in another letter of the same year, in which he reports that “large SUNFLOWERS” are his subject matter, he says, “I’m painting with the gusto of a Marseillais eating bouillabaisse.”14

What is mainly found in the letters is the opposite of madness. Van Gogh comes over as having had a clearheaded sanity about his periods of illness and a passionate commitment to his painting: “Strictly speaking I’m not mad, for my thoughts are absolutely normal and clear between times, and even more than before, but during the crises it’s terrible however, and then I lose consciousness of everything. But it drives me to work and to seriousness, as a coal miner who is always in danger makes haste in what he does.”15

He had a vision of what he hoped to do: “Sometimes I know clearly what I want. In life and in painting too, I can easily do without the dear Lord, but I can’t, suffering as I do, do without something greater than myself, which is my life, the power to create … And in a painting I’d like to say something consoling like a piece of music. I’d like to paint men or women with that je ne sais quoi of the eternal, of which the halo used to be the symbol, and which we try to achieve through the radiance itself, through the vibrancy of our colourations.”16

What his disorder almost certainly did contribute to his painting came from his “heightened sense of reality.” John Custance’s use of this phrase for his own manic episodes came in an account with strong echoes of both van Gogh’s paintings and his letters. Custance describes lights being deeper and more intense, sometimes like the Aurora Borealis. And people’s faces had a special quality: “I will not say that they have exactly a halo round them, though I have often had that impression in the more acute phases of mania. At present it is rather that faces seem to glow with a sort of inner light which shows up the characteristic lines extremely vividly.”17

Figure 13.13: Vincent van Gogh, Van Gogh’s Chair, 1888. London, National Gallery. Oil on canvas. Copyright © 2012 The National Gallery, London/Scala, Florence.

Aldous Huxley’s description of his own heightened visual experience after taking mescaline is also reminiscent of van Gogh: “I was looking at my furniture, not as the utilitarian who has to sit on chairs … but as the pure aesthete whose concern is only with forms and their relationships within the field of vision … But as I looked … I was … back in a world where everything shone with the Inner Light, and was infinite in its significance. The legs, for example, of that chair—how miraculous their tubularity, how significant their polished smoothness! I spent several minutes—or was it several centuries?—not merely gazing at their bamboo legs, but actually being them.” Later Huxley opened a book on van Gogh: “The picture at which the book opened was The Chair—that astounding portrait of a Ding an Sich, which the mad painter saw, with a kind of adoring terror, and tried to render on his canvas.” Although Huxley thought the painting inadequate to the vision, he thought van Gogh’s chair (Figure 13.13) was “incomparably more real than the chair of ordinary perception” and “obviously the same in essence as the chair I had seen.”18

Figure 13.14: Vincent van Gogh, Wheat Field with Cypresses, 1889. New York Metropolitan Museum of Art. Oil on canvas. Copyright © 2012. Image copyright The Metropolitan Museum of Art/Art Resource/Scala, Florence.

The intense sense of reality so visible in the paintings is also there in van Gogh’s letters: “Ah, while I was ill, damp, melting snow was falling, I got up to look at the landscape—never, never has nature appeared so touching and sensitive to me.”19 The intensity fired his energy to work: “Today I worked from 7 o’clock in the morning until 6 o’clock in the evening without moving except to eat a bite a stone’s throw away. And that’s why the work is going fast … At the moment I have a clear head, or a lover’s blindness towards my work. Because being surrounded by colour like this is quite new to me, and excites me extraordinarily. Fatigue doesn’t come into it; I could do another painting tonight, even, and I could bring it home.”20

Van Gogh’s inner disturbance is one reason his paintings do not have the serenity of, say, Vermeer’s. But it gave the blazing passion and the intensity that is part of what makes them great (Figure 13.14). As Karl Jaspers said, “The ground of the landscape appears to be alive, waves seem to rise and ebb everywhere, the trees are like flames, everything twists and seems tormented, the sky flickers.”21

Unlike Blake, van Gogh understood his own instability and his susceptibility to madness. His response to it was utterly sane:

I am a man of passions, capable of and given to doing more or less outrageous things for which I sometimes feel a little sorry. Every so often I say or do something too hastily, when it would have been better to have shown a little more patience … This being the case, what can be done about it? Should I consider myself a dangerous person, unfit for anything? I think not. Rather, every means should be tried to put these very passions to good effect …

So instead of giving in to despair I chose active melancholy, in so far as I was capable of activity, in other words I chose the kind of melancholy that hopes, that strives and that seeks, in preference to the melancholy that despairs numbly and in distress.22

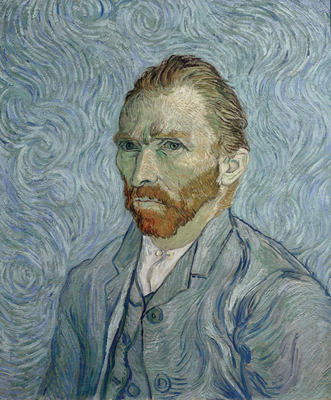

Both sides of van Gogh—the troubled passion and how it is put to good effect—are in the brilliant self-portraits. The tautness and intensity are visible in Figure 13.15. In his right eye (on the left) there is a glint of disturbance. But it is not an insane painting. It is a sane portrait of a sometimes tormented man by a painter of genius.

Near the end of van Gogh’s life, the illness is more visible in the letters. They show despair closing in. One of his last paintings, the Wheat Field with Crows (Figure 13.16), may be the most powerful expression ever given to one despairing view of the world. The dark crows seem sinister. The field and sky are seen as being in violent motion and, at the same time, as claustrophobically oppressive. The greatness of the painting comes partly from its making one kind of desperate state of mind intelligible from the inside.

Figure 13.15: Vincent van Gogh, Self-Portrait, 1889. Paris, Musee d’Orsay. Oil on canvas. Copyright © 2012. Photo Scala, Florence.

In a letter he wrote at the time, he said, “What can be done—you see I usually try to be quite good-humoured, but my life, too, is attacked at the very root, my step also is faltering … There, once back here I set to work again—the brush however almost falling from my hands and—knowing clearly what I wanted I’ve painted another three large canvasses since then. They’re immense stretches of wheatfields under turbulent skies, and I made a point of trying to express sadness, extreme loneliness.”

Figure 13.16: Vincent van Gogh, Wheatfield with Crows, 1890. Amsterdam, Van Gogh Museum. Copyright © 2012. Photo Art Resource/Scala, Florence.

These different works of art reflect the wide range of psychiatrically disordered experience, as well as the personalities and skills of the artists. Some of the pictures (those in Laura Freeman’s blog, Wilhelm Werner’s sterilization protests, and van Gogh’s paintings) express an undeluded view of the artist’s situation. At the other extreme is Jakob Mohr’s diagram of how his persecutors were reading his mind and controlling him. Others come somewhere in between. Adolf Schudel’s Steep Path or Aloise Corbaz’s Palais Rumine reveal disturbing inner worlds. The artist may or may not be in the grip of such a world at the time of painting, but clearly has experience of it.

The pictures are reminders of platitudes that matter. Not all psychiatric disorders involve delusions or insanity. The person who does suffer from delusions usually does not experience them all the time and may produce undeluded political protests or powerful—sometimes even great—art. And the power, sometimes greatness, of the art may owe something to the person’s psychiatric disorder.

The contribution of the disorder can be made in very different ways. If the account given earlier of Blake is somewhere near right, lack of “insight” about one’s delusions may even be helpful. Blake’s uncritically accepted “visions” and his ability to integrate them into his life may have had great importance. Their role in his quite unconscious creation of his own charged view of the world helped shape him and so his art.

If the account given of van Gogh is somewhere near right, his disorder contributed in a very different way. Between his mental breakdowns, he was entirely sane and was undeceived about his delusions. He used his painting to defend himself against insanity. He also used it to partly create himself: not numb despair but active melancholy. He had a deep need to be creative, together with ideals about the value he hoped his work would have in revealing things to others. But the role of his disorder was not just the negative thing his art was pitted against. (Though that gave to his work the urgency of the coal miner hurrying to escape danger.) Above all, it gave him the heightened sense of reality, the charged vision so many of his paintings express.

It may seem that these comments treat van Gogh’s paintings as mere symptoms of disorder, and reduce a great painter to merely a person with a particular psychopathology. That is a mistake. To say that a painter is expressing his or her own experience of psychological disturbance is not to discredit either the artist or the work. Aloise Corbaz’s painting gives the rest of us a glimpse of the inner experience of schizophrenia through being such a powerful expression of it. She was a considerable artist in being able to achieve this.

Having delusions, or knowing severe depression or mania, are aspects of human experience. As with fighting in war, only a minority have these experiences. But, again as with war, the experiences are often particularly intense. Someone is not belittled by being called a war artist, and it is no slight to say that someone’s art expresses the experience of psychiatric disorder. Vicariously, the rest of us grow deeper in our experience and understanding through the works of painters and writers who manage to convey something of either war or psychiatric disorder.

People who are bereaved, unemployed, persecuted, humiliated, or treated unjustly, or whose physical or mental health is damaged, respond to disaster in contrasting ways. Some are diminished: becoming passive, defeated, vengeful, or bitter. Others respond with resilience, courage, generosity, or creativity. When the disaster is mental disorder, the world can be enriched. Van Gogh or Dostoyevsky might not have created their great works if some ideal cure had been available. The tension is clear. We would not wish to be without their work. But major psychiatric disorder is so horrible, we would also not wish it on anyone. Methods of prevention and cure (medication, therapy, different ways of treating children, and such) should be developed. Of course we do not want to retain conditions blighting lives, even if they are a stimulus to great art. But while these conditions do exist, we are right to feel pleasure—and sometimes awe—at the ways, both creative and self-creative, in which people can put these very passions to good effect.