“A Skill So Deeply Hidden in the Human Soul”

Isn’t the eye part of the mind?

—David Hockney

The schematism by which our understanding deals with the phenomenal world … is a skill so deeply hidden in the human soul that we shall hardly guess the secret trick that Nature here deploys.

—Immanuel Kant

We are not the only interpreting animal. The fox interprets the sounds and smell of hounds as a threat, the hawk interprets the mouse’s movement on the ground as food, and so on. But no other species on our planet has developed any serious competitor to the discriminating powers of human language or to our scientific powers of interpreting the natural world. And we are unique in the subtlety of our interpretation of ourselves and each other.

For me, a landscape does not exist in its own right, since its appearance changes at every moment; but the surrounding atmosphere brings it to life, the air and the light, which vary continually …

Other painters paint a bridge, a house, a boat … I want to paint the air in which the bridge, the house, and the boat are to be found—the beauty of the air around them …

To me the motif itself is an insignificant factor; what I want to reproduce is what lies between the motif and me.

—Claude Monet

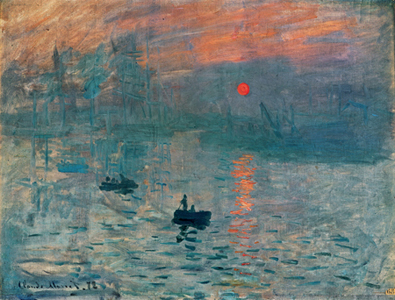

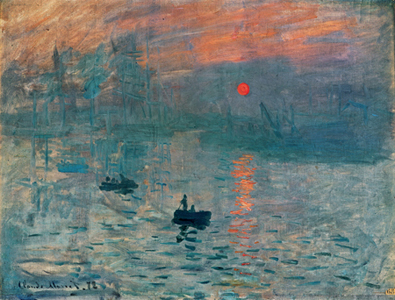

Figure 7.1: Claude Monet, Impression au soleil levant, 1872. Paris, Musée Marmottan. Copyright © 2012. Photo Scala, Florence.

The Impressionist painters hoped to strip off our framework, to show “what lies between the motif and me”: our fleeting glimpses of the world before we interpret them. The innocent eye saw a world of light and colors washing into each other, without the sharp edges of imposed categories: bridges, houses, and boats (Figure 7.1).

But a blind person given sight would not see the world as a painting by Monet. Seeing the world as intense patches of color where air, light, and water blur together can be wonderful. But it is still an interpretation. Ernst Gombrich said, “The innocent eye is a myth.”1 Some painters agree. David Hockney knows the limits of photographs in reflecting experience: “I’ve always assumed that the photograph is nearly right, but that little bit by which it misses makes it miss by a mile … Picasso and Matisse made the world look incredibly exciting: photography makes it look very, very dull … the camera sees geometrically. We don’t. We see partly geometrically but also psychologically … Isn’t the eye part of the mind?”2 The innocent eye is a myth because we see psychologically. Our experience is permeated with active interpretation.

Immanuel Kant saw the huge question this raises. How does the mind impose categories and concepts upon the flow of experience? Despite his own philosophical work of genius on the question, he was pessimistic about unraveling a skill so deeply hidden in the human soul. The question is still daunting. But luckily philosophers guessing at Nature’s secret trick are no longer on their own. The mechanisms of interpretation are yielding a bit to cognitive psychology and neuroscience.

How much we interpret our experience is shown by visual agnosia. In this cluster of neurological disorders, people still see colors and shapes but have problems interpreting them. Varieties of agnosia bring out the complexity of the processes of interpretation.

We see an object from a particular angle. Knowing how it will look from other viewpoints is part of recognizing it as a cup or a hammer. This depends on integrating the seen shape and color with remembered experience of the structure of objects. Sometimes what is impaired is this ability to “construct” an object such as a hammer from its shape and color. Tests show that people with this problem have trouble recognizing things photographed from unusual angles and recognizing letters or pictures from incomplete images.3 Cases of total agnosia are rare: a person may be able to tell mammals, birds, and insects apart, but not be able to discriminate within these categories. Or there may be problems with recognizing animals but not with recognizing flowers.

People with agnosia may come closest to the “innocent eye.” One such person, “John,” was left with visual agnosia after a stroke.4 He has difficulty describing his experience, but his visual world does not seem the same as that of an impressionist picture: “The nearest description I can get to is to say that everything is slightly out of focus, though not to my eyes you understand, but to my brain … although I can recognise many food items seen individually, they somehow seem hard to separate en masse. To recognise one sausage on its own is far from picking one out from a dish of cold foods in a salad: a case of ‘can’t see the trees for the wood’?”5 This was given some support by one test he was given. He was shown a large letter made up of a string of repetitions of another letter in smaller size. For instance, a sequence of the small letter s, laid out in the shape of a large H. He was quick at seeing the H, but—not seeing the trees for the wood—he was slow seeing the smaller letters that made it up.

In the other major (though very rare) type of visual agnosia, the hammer is seen as the three-dimensional object that it is, but the ability to interpret its “meaning” (a tool for driving in nails) is lost. One person with this type of agnosia who was shown a stethoscope could describe its shape (a “long cord with a round thing at the end”) but thought it might be a watch. Asked to show what one might do with it, he treated it as a watch.6

Not all neurologists have agreed that what is disrupted in these conditions is recognition. Norman Geschwind once claimed that most classical forms of agnosia are disturbances of naming, caused by parts of the brain that receive the visual input becoming disconnected from the speech area. People with this disconnection may be reluctant to admit they cannot answer a question. The responses they confabulate may give the misleading impression of a perceptual problem.7 But this model of a naming problem does not fit all cases. John, mentioned above, was bad at recognizing pictures of famous faces. But he said that the Queen, the Duke of Edinburgh, and Princess Anne were politicians. His problem is about recognition, not just naming.8

Geschwind thought it was a mistake to accept a special class of “defects of recognition” somewhere between defects of perception and defects of naming. He argued that “recognition” is not a single function, but is seen whenever someone makes an appropriate response. This may be words, gestures, drawing, and so on. He claimed that “this view abolishes the notion of a unitary step of ‘recognition,’ ” and that we need to think in terms of the whole pattern of responses and of their failures.9

It is hard to dispute that a proper account of someone’s problem needs this fine-grained analysis of particular responses. But might there also be a behaviorist dogma here? Recognition is normally manifested in words, actions, and so on. But even when it cannot be manifested, it may still exist. (There are many ways to show you have heard something. But there is still such a thing as hearing.) We do recognize things, although doing so is more fine-grained and variegated than we once thought. Kant’s “skill so deeply hidden in the human soul” is coming into view as neuropsychologists unravel the implications of impairments caused by different kinds of brain damage, and use electrodes and neuroimaging to map the mechanisms of interpretation as they function in the undamaged brain.

Members of some other species can tell whether another animal’s movements are goal directed or random. Dog owners notice that a dog may react strongly to movements specifically aimed at getting hold of the dog’s leash. Primates make such interpretations. If a capuchin monkey sees two people, each with an opaque box, one moving a hand randomly inside the box and the other moving a hand inside the box as if making an unsuccessful attempt to reach inside and get something out, it will go to the second box but not the first one.10

What are the processes involved in recognizing actions? Motor cells, neurons firing when bodily movements are made, often have specific links, some to hand movements; others are finer-grained, linked only to grasping, tearing, holding something, or taking food to the mouth. Studies of macaque monkeys with electrodes in their brains showed some of these motor cells firing when someone else made a particular movement. A passive monkey seeing another monkey grasp something would have a burst of firing in a “grasping” cell. It is claimed that, in humans, these “mirror neurons” are involved in recognizing intentional action.

The claim is controversial. Human brain lesions that disrupt the motor processes used in sign language do not disrupt recognition of sign messages.11 And there is a problem about describing actions. There are different levels at which the “same” action can be described: squeezing a trigger, firing a gun, assassinating an archduke, starting the First World War, and so on. What exactly is it, to “recognize an action”?

Some mirror neurons generalize from one sense to another. Those firing when we kick a ball also fire when we see or hear a ball being kicked. Some make very subtle discriminations. Those firing when someone else is seen to grasp something also respond when a graspable object is seen “in person”—but not when its image is seen on a screen. They fire only when the object is near, and more strongly if it approaches fast. In a monkey, some of these neurons fire only when it sees the two-finger grasp used for small objects. Others fire at the sight only of the whole-hand grasp used for large ones. They do not fire when the action is mimed without the object. If the “object” is out of sight, firing is affected by memory of whether or not it is actually there.12

Although the link between mirror neuron firing and “action recognition” is still controversial, the selectivity does suggest that there is a link between their firing and recognition. Despite the many actions a physical movement may embody, these cells seem to discriminate between some intentions. Grasping something to eat and grasping it to put it in a box may look the same. But some cells fire only when food is grasped to eat and others fire only when it is grasped to put it into a box. Possibly the mirror neurons’ response is not the key neurological basis of interpretation but instead draws on interpretations or memories in some other brain region.13 Either way, this sensitivity to intentions goes beyond interpreting events as movements. A boundary is crossed, and movements are seen in terms of minds and actions.

Philosophers discuss the classical problem of other minds. How do we know other people are conscious? Could they not be unconscious robots, programmed to behave as if they have experiences as I do? As a teacher of philosophy, I find this question fascinating. Outside philosophy, sane people no more worry about it than they worry about whether the physical world is a figment of their imagination. Philosophers do not disagree with the sane view on these questions—they take up the intellectual challenge to explain why it is right.

Although sane people are not anxious about whether other people are conscious, they do sometimes care about a more everyday “other minds” problem: How much do we really know what other people are thinking or feeling? People disagree about how easy or hard it is to understand other people. There is a continuum of views, which can roughly be said to stretch from Gilbert Ryle to Marcel Proust.

Gilbert Ryle wrote: “The ascertainment of a person’s mental capacities and propensities is an inductive process, an induction to law-like propositions from observed actions and reactions. Having ascertained these long-term qualities, we explain a particular action or reaction by applying the results of such an induction to the new specimen … These inductions are not, of course, carried out under laboratory conditions, or with any statistical apparatus, any more than is the shepherd’s weather-lore, or the general practitioner’s understanding of a particular patient’s constitution. But they are ordinarily reliable enough.”14

Marcel Proust was more skeptical. His own view was reflected by his autobiographical novel’s narrator. The question arose in his childhood: “When Françoise, in the evening, was nice to me, and asked my permission to sit in my room, it seemed to me that her face became transparent and that I could see the kindness and honesty that lay beneath. But Jupien … revealed afterwards that she had told him that I was not worth the price of a rope to hang me, and that I had tried to do her every conceivable harm.” He realized he could never know for certain whether Francoise loved or loathed him. This shock to his view of her made him have more general doubts about the pictures we form of other people:

And thus it was she who first gave me the idea that a person does not (as I had imagined) stand motionless and clear before our eyes with his merits, his defects, his plans, his intentions with regard to ourselves (like a garden at which we gaze through a railing with all its borders spread out before us) but is a shadow which we can never penetrate, of which there can be no such thing as direct knowledge, with respect to which we form countless beliefs, based upon words and sometimes actions, neither of which can give us anything but inadequate and as it proves contradictory information—a shadow behind which we can alternately imagine, with equal justification, that there burns the flame of hatred and of love.15

How far are our interpretations of other people’s mental states reliable? What is the right place on the continuum between Ryle’s inductions that are “ordinarily reliable enough” and Proust’s “shadow which we can never succeed in penetrating”? What resources can we draw on in making these interpretations?

All gaps in actual knowledge are still filled with projections. We are still almost certain we know what other people think or what their true character is. We are convinced that certain people have all the bad qualities we do not know in ourselves or that they live all those vices which could, of course, never be our own. We must still be exceedingly careful not to project our own shadows too shamelessly; we are still swamped with projected illusions. If you can imagine someone who is brave enough to withdraw these projections, all and sundry, then you get an individual conscious of a pretty thick shadow.

—Carl Jung, Psychology and Religion

We have seen how our experience is permeated with interpretation. We see a spoon or a hammer only through complex and subtle unconscious interpretation. The complexity and subtlety increase when we turn from things to people.

Our intuitive interpretation of people is not something we think through, but an impression that forces itself on us. These involuntary intuitions can be important in criminal trials. In a trial discussed by Janet Malcolm in The Journalist and the Murderer, the jury heard a recorded interview by the person accused of murder. One juror is reported to have said, “Until I heard that, there was no doubt in my mind about his innocence. All the evidence had just seemed confusing. But hearing him turned the whole thing round. I began to look at everything in a whole new way. There was something about the sound of his voice. A kind of hesitation. He just didn’t sound like a man telling the truth.”16

Of course we can go beyond these intuitions to more reflective interpretation. A skeptically minded juror might wonder about the reliability of the intuition about the accused person’s voice. One way of testing it might be to question some of the “confusing” evidence. Does the defense story seem coherent? Are there facts it does not fit? How well established are these facts? How well does the prosecution case do on these tests? And so on. As well as “external” tests about forensic evidence and alibis, there is the question of the relative psychological plausibility of each of the two cases. What motives and beliefs does each ascribe to the accused? Which version of his psychology makes more sense?

In this contrast, there may be a blurred boundary between intuitive and reflective interpretation. There may be unease about the intuitive hearing of the false note in the man’s voice. This might be the residue of basing earlier misjudgments on how people sounded. And the carefully reflective interpretation of the evidence may rest partly on beliefs about psychological plausibility that are more intuitive than rational. The intuitive-reflective contrast may be more of a continuum than an unbridgeable gulf. But here, with this in mind, we can consider the differences between interpretations toward each end of the continuum. Starting at the intuitive end will lead into reflective interpretation.