It was mid-morning and the gong-gong man was drunk. We sat, visitors in cheap folding camp chairs from the back of our Tata pickup truck and villagers in molded plastic patio chairs, under the canopy of a mango tree thick with weaver nests that hung like Christmas ornaments. The village of Ampedwae, near the regional capital of Koforidua, is like countless others in Ghana—countless because many are not on the government maps or even on an actual road and may go by several different names, depending on whom you ask and whether they speak Twi, Ewe, Ga, Hausa, or one of the more than seventy other languages and dialects of the country, not counting the official English.*

Villages in Ghana often have names that are devotional or inspirational in meaning. Ampedwae means “you should not boast” in Akwapim (the dialect of Twi spoken here)—advice the village seems to have taken to heart. Other than a stuccoed blue-and-beige schoolhouse, the built environment of Ampedwae is barely removed from the natural world: just a few dozen rectangular wattle-and-daub huts with bamboo or raffia roofs, their mud walls slowly melting from the rain back into the landscape, as if smeared together in wet oils by an artist. There would be no rain today; January is the dry season, which is one of the only ways to distinguish seasons in a country where every day of the year is hot and begins and ends around six o’clock. In January all of West Africa is dry, and the wind known as the Harmattan picks up the Sahara Desert—all 3.5 million square miles of it, as far as I could tell—and blows it south to the Gulf of Guinea—a thick, choking haze that stings your eyes and clogs your nose with the same brick-red dust that coats the broad leaves of the banana palms. Ampedwae—no electricity, no well—is bisected by a road of the same red dirt, and whenever a beaten Nissan bush taxi bounces by at high speed (which is the only speed driven in Ghana), it churns up a wall of dust that breaks like a tsunami over the squat village, scattering chickens and goats.

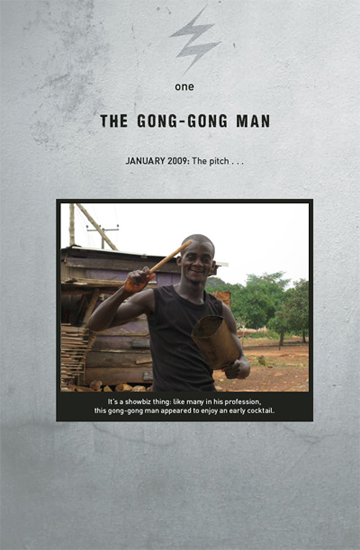

“Okay!” The gong-gong man rose shakily from his seat under the mango tree, stood at attention, and saluted us crisply with his right hand. In his left hand he held the village gong-gong, which is a hand-forged cowbell, and a foot-long stick. He wore brown polyester pants, sandals, and a filthy tan bowling shirt missing several buttons. In the back pocket of his slacks was jammed a liter-sized bottle of local gin, which must have made sitting as difficult as its contents had evidently made standing. He spoke rapidly in a slur as hard to grasp as mercury, while scribbling the air with his stick. I trained my digital camera on him and shifted the switch to video, which is why I know exactly what he said: “I know ya I say now listen up, so yo-yo come, ya make goo-gong. Okay.” (Two raps of the gong-gong with the stick.) “Good-morning-good-morning-good-morning! How are you? Thank you! You are always will be here. You come and speak to us in under the good to Arno. Jesus la-la, Ampedwae, that’s right. I going out now call every Jedi better come now and cure the sow.”

At least that’s what I got. It could have been a figure of speech. “Thank you,” he concluded with a low bow. “God bless!” And he staggered down the road banging the gong-gong and announcing in Twi, “Aggo! Aggo!” Listen up!

Soon more villagers, alerted by the dull clang of the gong-gong, joined those already assembled under the tree. It was Thursday, which is rest day in Ampedwae—meaning the men were not tending their small cassava and cocoa plots and thus available for a town meeting. In theory the children would be at school, but although public school is free, many Ghanaian families cannot afford the required uniforms and books; children are also needed for labor—caring for smaller children, hauling water and wood, and tending animals. So throngs of barefoot kids in underwear waved from across the road, squealing “Obruni! Obruni!” which is Twi for “beyond the horizon” but in Ghana universally means “white man.” (The Ewe slang for white man, yevu, seems to have originally meant “trickster dog,” although this is debated.)

The children knew better than to cross the road. Important town meetings are for adults, and children in Ghana keep a prudent distance from their elders—not just out of respect. In Ghana if you beat someone else’s child, his parents will thank you; the child must have deserved it. Other than Harper, my seventeen-year-old son, the only minor under the mango tree was an infant sucking at his mother’s breast. She was one of just three women in the group of more than thirty. “Where are all the women?” I whispered to Jan Watson, who was sitting next to me in one of our camp chairs.

“Busy,” she said. “Somebody has to pound the fufu,” she added, referring to one of the national staples—boiled cassava and plantain pulverized in giant wooden mortars and formed into dumplinglike balls that are eaten by hand, dipped in peanut or palm nut soup. But soon enough the women straggled up, abandoning their long fufu pestles, and the meeting began. Ghanaians respect traditional gender boundaries—women cook and carry towering loads on their heads, men farm and carry machetes, sometimes on their heads—but some ethnic groups, like the Ashanti, are matrilineal: status is determined by your mother’s family, a practical arrangement considering it is generally easier to be certain of your mother than your father. And in much of this predominantly Christian country, even Islamic women hold jobs, vote, frequent beauty salons (in roadside shacks on virtually every block), and allow the men to pretend they are in charge.*

Around strangers Ghanaians are formal, even courtly, so the first order of business was to shake hands with several of the important elders—ending with the village chief, a modest but mildly officious middle-aged man who seemed like the type who would refer to Robert’s Rules of Order at an Elks Club meeting. His attire, an orange sport shirt and impeccably pressed sage green slacks, would not have looked out of place at the Seal Harbor Yacht Club. Every handshake ended with the elaborate Ghanaian mutual finger snap, along with the standard greeting “You are welcome!”—used in Ghana as we would say “Welcome to my home” and not as a rejoinder to “Thank you.” The local dignitaries moved down the receiving line, ending with my brother Whit.

Whit was born a few weeks before Barack Obama, who at age forty-seven had been sworn in as President the previous week. He is four years younger than I yet even grayer, his hair having progressed at a relatively young age to Steve Martin silver. He was wearing trendy gunmetal eyeglasses, a batik print shirt, high-tech travel pants, and khaki Crocs—the standard uniform of the hip West Coast entrepreneur. “Ties are for losers,” Whit once told me.

Not that anyone in Ampedwae would have known that. In Ghana, a necktie means you are an important person, a college man, possibly even a Big Man, with a good job that doesn’t require a machete. You might even work in an office that’s air-conditioned and be able to sleep at your desk. Appearances matter: this is why Ghanaian men with office jobs tolerate ties and double-breasted woolen suits in blast-furnace climatic conditions. So Whit was bucking local custom, but he bowed formally as each village elder shook his hand. Then everyone sat down and waited for him to talk.

“Good morning,” Whit began. “Mente Twi.” His admission that he did not speak Twi seemed to amuse the villagers, both for its contradiction (didn’t he just say that in Twi?) and its self-evidence (white people rarely speak Twi). “We are starting a new company and we want to tell you about it,” he continued. “It’s a new way to use batteries that we think you will like. But first I’d like to tell you a little about myself. My name is Whit Alexander, and I am American.”

After each sentence a man I’ll call Kevin, Whit’s first Ghanaian employee—short, stocky, goateed, and a former stage and TV actor in the capital of Accra—would translate into Twi, which required approximately five times as many words as the English version. (“Sometimes people would not understand the meaning so I have to embellish,” Kevin told us later.) Most of the villagers spoke at least some English, so their reactions to Whit’s original words and Kevin’s translation reverberated like an echo chamber.

Whit continued: “I lived for many years all over West Africa. I did one year of university in Abidjan, Ivory Coast. After college I lived for a year in Niamey, Niger, working on a grain-marketing project. Then I spent two and a half years in Bamako, Mali, on a farming project. I have also traveled through Senegal, Gambia, Mauritania, and Burkina Faso. Now that my children are almost grown, I decided it was time to come back to Africa and start the business that I have always wanted to do.”

“Farming projects” aside, as far as I was concerned Whit had been an Africa-based CIA agent. He’s never admitted it, but then they don’t tell their brothers, do they? After graduating from Georgetown’s School of Foreign Service, Whit and Shelly (then his fiancée) did live in West Africa for several years. During that period I couldn’t help but notice that for an African agricultural expert Whit knew almost nothing about farming. Yams, coconuts, carrots—all were the same to him. He called soil “dirt,” none of which could be seen under his fingernails. And he seemed to spend a lot of time off the farm, in places like Washington, D.C., and the United Nations. Who was minding the melons? Letters to him had to be addressed via the State Department diplomatic pouch. Sometimes, on his U.N. visits, he would stay in my apartment in Brooklyn. Once after he went to bed I riffled through his wallet and found all sorts of official embassy clearances and passes. Confronted, Whit said he would now have to kill me. Then he pointed out that all the credentials were in his own name and granted him access to low-level areas like the American recreation center and the shopping co-op. I wasn’t convinced. They practice saying that kind of stuff to throw you off track. In Bamako his private compound and swimming pool were guarded by a psychopathic monkey named Boo Boo who had fangs and was not afraid to use them. (He bit Shelly.) It was all right out of Dr. No.

At any rate, by 1990 Whit was back in the States and living in Seattle, Shelly’s hometown. He dropped out of grad school in 1992 to take a job at Microsoft, where he produced the maps for the first Encarta Encyclopedia and then led the design and development of the more detailed Encarta World Atlas. (CIA agents would know a lot about exotic foreign maps, wouldn’t they?) That was the stock-option heyday at Microsoft, when secretaries hired in the 1980s were retiring as multimillionaires. Whit came too late to win a game-ending jackpot, but after five years he too had “retired” at age thirty-five with enough options to sit back and plan his next move.

Within eight months he was off on a new venture, which became Cranium. After a ten-year ride to the top of the toy business, Whit, his partner, Richard, and their investors sold Cranium to Hasbro for more than seventy-five million dollars. With discretion reminiscent of his shrouded former “farming” work in Africa, Whit maintains that very little of that sum was available once investors and other debts had been paid off. All I know is, Whit then “retired” a second time.

The gong-gong man had returned. His bottle was empty.

“I respect how hard Africans work to provide for their families and build a better life,” Whit went on, ignoring the fact that at least one community member was inebriated before noon. “I know that sometimes there are better ways to get things done. I have been searching for new ways to help people in Africa do more with their lives.”

Growing up in a middle-class suburb of Grand Rapids, Michigan, Whit and I were not particularly close. He was the annoying kid brother who would tell your parents if he knew what was really happening after school. Whit was a techie nerd, before that term existed. He and some even nerdier buddies were programming a Wang microcomputer in high school, less than two years after Paul Allen had shown Bill Gates the first Altair microcomputer, which inspired them to launch Microsoft. By contrast I got through four years of college on an electric typewriter and a bottle of Wite-Out. Computers were forced on me by the workplace. “Here’s a press release,” said the editor on my first day as a salaried journalist. “Gimme a story by six.” I peered at the blank screen on my new desk. “You need to turn it on first,” he added.

Our parents divorced when I was seventeen. I got an apartment with a buddy, and Whit moved with our mother to Tucson, entering the slipstream of Sun Belt immigrants. That was the end of our life together, and for a while it seemed as though our paths would never again cross except at weddings and funerals. I was a rebellious loner, angry with my parents for their failed marriage and angry with myself for letting it happen. Anything my parents wanted me to do, such as college or even attending my high school graduation, I resolved to do the opposite. So I checked out. I drifted through jobs around the country. That might have continued forever had I not met Sarah, my future wife, an aspiring actress who was also trying to figure out who she was, albeit with considerably more poise and planning. Together we moved to New York, where I enrolled in college at age twenty-six.

Whit did everything in the proper order. He went to college right after high school. He never worked in a restaurant. He got good jobs, saved money, and tossed around phrases like “scalable business.” He had financial planners and the right kind of insurance. Our dad, who fancied himself a keen judge of character, used to say, “Whit will get rich but Max will be famous”—not realizing in his Midwestern way that except in the case of presidential assassins, fame and fortune generally go hand in hand. Whit seemed on a path for both, and I wasn’t strongly motivated for either.

And yet despite our differences, or maybe because of them, Whit and I grew closer over the years—or as close as two brothers could be who lived three thousand miles apart and saw each other once every few years. Our wives and children became friends. We shared a sense of humor, a love of wisecracks and mutual insults. Around me, Whit could loosen his (metaphorical) tie, shed the corporate jargon, and be a kid brother again. I wish I could say something lofty like we completed each other, but mostly what we did was make a safe place for fart jokes.

None of which could have indicated that someday we would be doing business under a mango tree in a village in Ghana.

“Don’t fuck this up, asshole,” I said, trying to be helpful. “You should have learned more Twi.”

“Shut up,” Whit whispered. I blew my nose and voided several ounces of red dust. Whit continued with his spiel:

“Our company is called Burro, and our goal is to help people do more. But I have to be honest with you. I am also trying to make money.”

This brought polite laughter that, for a second, seemed in danger of breaking into a gale. It was unclear to me if the villagers were laughing with us or at us, but Ghanaians have a sharp sense of humor and are especially attuned to the absurd. When four obrunis show up in a brand-new pickup truck, they are either volunteers, Peace Corps workers, NGO reps, or governmental aid agents, all of whom are giving something away. But we were not building wells, digging latrines, or painting orphanages. In fact we were giving away nothing except a leftover stash of Obama campaign pins, and we were getting seriously low on those.

No, they understood that we had come to this village to convince thirty-three of the roughly one billion people on Earth who live on a dollar a day to give us some of their money.

As George Burns said, “If they laugh, it’s funny.”

“I believe Burro can only serve you continuously and sustainably if we make it a viable, profitable business,” said Whit, bravely pressing on. “Then we can always be there for you.” Although he didn’t come out and say it, he was alluding to the problem of NGOs mobilizing an ambitious “project,” then disappearing when the funding runs out—a problem all too familiar to rural Ghanaians. “We want to do many things, but our first idea is one that if you use a lot of batteries, you should be able to save money and do more. We want you to help us decide if the Burro offering is right for you.”

A village man stood and said in Twi: “Tell us what these batteries do.”

It would be hard to overestimate the obsession with batteries in African villages with no electricity. For rural Ghanaians who live off the grid (in a country just north of the equator where darkness falls between five-thirty and six-thirty year-round), batteries power two essential appliances: flashlights and radios. Flashlights allow villagers to hunt at night for snails or bigger game like antelope and large rodents (all a significant source of income and protein), for children to do homework after dinner, and for villagers to feel safe after dark. (Perhaps because they have so little faith in law enforcement, Ghanaians are obsessed with security. Even remote village crop depots have more locks and bars than a Forty-seventh Street jewelry store.) Flashlights are also important in electrified cities, where streetlights are rare and the pavements present minefields of pedestrian obstacles, from sinkholes to open sewers to the mangled carcasses of wrecked autos that no one can afford to tow away. When you are walking around a dark African city at night, a flashlight can mean the difference between life and death.

Portable transistor radios offer many Ghanaians their only source of electronic news as well as entertainment. They listen to homegrown reggae stars like Blakk Rasta, who recorded a hit anthem to Barack Obama; the indigenous “highlife” beat that evolved after World War II from American jazz and R&B; its modern rap-inspired version, “hiplife”; and a particularly skin-crawling version of gospel music that is unfortunately not limited to Sunday mornings. Then there is the news. Ghana has a lively free press, and radio news is delivered at a constant yell in several languages. Life in Ghana happens out of doors (as near as I can tell, everything except sex takes place under trees), most of it to the soundtrack of a blaring boom box. This is not regarded solely as entertainment; farmers who bring their radios into the fields—those who do not superstitiously believe that music attracts snakes—claim to have more energy and be more productive.

A new use for batteries is evolving along with the adoption of cell phones, which are inexpensive in Ghana and have become the first and only telephone for most people. Of course, cell phones have proprietary batteries that need to be recharged, and when you don’t have electricity this presents a problem. Enterprising locals gather up phones in remote villages, then take them to the nearest on-grid charging location. But with fees approaching a dollar for a single charge if you factor in transportation costs, Africans are eager for a better solution. A handful of Chinese manufacturers have introduced cheap portable phone chargers that use a single AA battery to charge the internal phone battery. But their quality is uneven (some refuse to work right out of the box), the adapters included don’t work on every phone, and the cheap non-alkaline AA battery available in Ghana isn’t powerful enough to operate them at all. Whit was already looking into producing better battery-powered phone chargers, a product line that would not occur to anyone operating from an office in Europe or America.

“How many of you use batteries?” Whit smiled; he knew almost every hand under the mango tree would go up. One man stood and held up his radio. He opened the back, revealing three Tiger Head brand D batteries—cheap Chinese carbon zinc models, sold everywhere in Ghana, that perform poorly and are prone to leaking.* The man said he changed the batteries about once a week. Even these crappy batteries are a big expense for rural Ghanaians, who must work about half a day to buy a pair.

Whit pulled a battery out of his pocket—vibrant green with a black logo of a donkey on it. “This,” he said, “is the Burro battery.” It was, in fact, a rechargeable nickel metal hydride AA battery. “It looks small, but it has as much energy as the Tiger Head.” From his other pocket he withdrew a matching green plastic tube the size of a D battery, then he inserted the AA battery into the adapter sleeve. “And it can be used like a Tiger Head.” The audience gasped.

“The cost is 75 pesewa per month, per battery,” said Whit. “Now, I know that is three times what you pay for a Tiger Head, but you are not really buying the Burro battery; you are buying the power inside. Burro batteries are fresh anytime you want. When the battery falls”—the charming Ghanaian term for a dead battery—“you take it back to your agent and get a fresh one—no pay. So if you use Tiger Heads and change them more than three times per month, you will save with Burro—and you can use ours all the time. So you can do more.”

Do More was the Burro slogan, which Whit had craftily worked into his pitch.

A man held up a lantern-type flashlight that took four D batteries. He was already a Burro customer, he explained, having arrived from another village. “I used to turn my light off before sleeping,” he said in Twi. “Now I leave it on all night for security.” We could not have asked for a more ringing endorsement had we planted him in the crowd.

“There are other advantages,” said Whit. “Has anyone ever had a Tiger Head leak and damage their device?” Many hands went up. “Burro batteries are better. If one ever leaks and spoils your device, bring us the battery and the device, and we will make it right. Finally, has anyone ever seen a child playing with a used battery they found on the ground?” Heads nodded. “It’s not safe. With Burro, you don’t throw them away.”

A hand came up in the crowd. “What happens if my battery falls at the end of the month?” the man asked. “Do I have to pay to get it fresh?”

Jan joined in. “Yes,” she said. “You are just using the batteries for a month; then you must pay for another month, whether the battery is fresh or fallen.” Resorting to terminology now widely understood from the burgeoning cell phone market, Jan clarified, “You prepay one month. You get power from the battery that whole month. Then you prepay for the next month.”

The man’s question got at one of the biggest challenges in the Burro business model. Ghanaians don’t really have a rental culture; despite the clearly compelling advantage of the offer, it takes time to explain to potential customers the basic idea of buying a service, as opposed to buying the physical battery. This is one reason why Burro was building its own network of trained agents who could explain the company’s unconventional offering. A direct relationship between client and agent also ensured a level of trust that would enable the rental model to work. In a country with no reliable legal system for dispute resolution, and where most people have no identification, no bank account, and no street address, renting valuable merchandise to them for a fraction of its cost carried considerable risk. “You can’t just set up shop on any street corner and hand out batteries to the first person who walks by,” said Whit.

So far the most promising agent was Whit’s man in Ampedwae—a local assemblyman named Gideon, with graying hair, a Fu Manchu mustache, and an entrepreneurial flair that impressed Whit and Jan. I found Gideon’s competence somewhat undercut by the fact that he worked out of a Spider-Man backpack, but after a while you get used to things like that in Africa, which is flooded with secondhand clothing and sports gear from America. I never saw a Brady Bunch lunch box, but it wouldn’t have surprised me. After Whit finished his presentation, Gideon, who had organized our village sales meeting under the mango tree, opened up his backpack and promptly signed up several more customers. Later he explained that many Ghanaians distrust other Ghanaians and are reluctant to part with cash for a promise of “fresh” batteries that may or may not materialize. “They might not believe me,” said Gideon, “but if the obruni shows up, they figure it must be real.” At least until the brand was established, it was becoming clear that village “gong-gong” meetings would continue to be a valuable sales strategy.

The downside to the Ghanaian’s good nature is that it can be hard to get at the truth; often, in the interest of politeness, deference, or perhaps some more calculated ruse that I have not yet gleaned, he will tell you what he thinks you want to hear. So Whit was working hard at training his associates to talk straight with him. “Tell me,” Whit asked Gideon as we were loading up the truck, “what could I have said better?”

“You might have talked about the environment,” he said thoughtfully. “You know, you mentioned how the old batteries are dangerous for children, and that was good, but I would also talk about how our batteries do not litter their village.” It was a good point, albeit one riddled with contradiction. Ghanaian cities are filthy, and people litter with abandon. For all its Eden-like rain forests, vertiginous waterfalls, and flocks of exotic birds and butterflies, modern, urbanized Ghana is no paradise. But these small ancestral villages are conspicuously tidy. The trees along the main roads are often pruned into aesthetic submission, and purple bougainvillea vines are artfully trained over entranceways. The floors of the village huts may be of dirt, but they get swept several times a day. Even the outdoor spaces are swept daily, leaving the unintentional broom tracks of a Zen garden. I wondered if it was part of the Ghanaian ownership culture: big cities don’t really “belong” to anyone, but these villages represent home and family, even for Ghanaians who have left the farm. I wasn’t sure yet how Burro would fit into that proud, poor culture, but I was beginning to see that the only way to do business here was to respect the simple logic of village life. When we sat under the mango tree and followed the rhythm of the gong-gong, we did well.

“Now, before you go, I have a present for you,” said Gideon. From the bed of the truck he hauled out a four-liter plastic jug with a loose-fitting cap and sticky white foam oozing from the lip. “Fresh palm wine, very sweet!” Gideon poured the unfiltered milky brew into a plastic cup; specks of dirt and a small bug or two floated like coffee grounds on the surface. “Don’t worry about the dirt, we always pour the first sip on the ground for our ancestors,” he said. “They don’t mind.” He tipped the cup in front of him and poured off the dirt, took a slug, and passed the cup to Whit. “Today we rented many batteries,” he said. “To Burro.”

As Bill Gates freely acknowledged, he did not originate the idea of doing good by doing well. As far back as 1959, the Pakistani activist and social scientist Akhter Hameed Khan realized that charity on its own was unsustainable as a model for third-world development. He pointed out that infrastructure such as schools, wells, and sewers needed ongoing maintenance; simply building them wasn’t enough. Who would pay for their upkeep after the volunteers left town? Working with the Pakistan (now Bangladesh) Academy for Rural Development, Khan initiated the Comilla Cooperative Pilot Project, a system of local cooperatives that integrated public and private enterprise to improve roads and irrigation systems, train administrators and accountants, and develop village economic plans that would carry improvements forward. Other programs followed.

Khan’s initiatives had varying degrees of success but were ultimately hampered by a lack of central control. In the 1970s, building on the work of Khan, the Bangladeshi economist Muhammed Yunus began developing a model for a centralized bank that would finance small rural businesses at more favorable rates than those offered by local moneylenders. Traditional banks ignored this market because it was difficult to enforce repayment contracts. But Yunus realized (this was his breakthrough) that when loans were made to groups of villagers (mostly women), repayment was essentially self-enforced by peer pressure. If someone did not pay back her loan, no one else in her group could take out a new loan. Thus was born the concept of microfinancing. In his book Banker to the Poor: Microlending and the Battle Against World Poverty, Yunus wrote: “We were convinced that the bank should be built on human trust.” Yunus’s Grameen Bank (which means “village bank”) has now loaned more than ten billion dollars to poor families while experiencing very low default rates; his success has inspired similar banks all over the world.*

In 1980 the American management consultant Bill Drayton founded Ashoka: Innovators for the Public, a sort of nonprofit venture capital firm dedicated to encouraging innovations that serve the world’s poor. Drayton popularized the catchphrase “social entrepreneurship.” In this context, entrepreneur did not necessarily mean someone looking for financial profit, but rather someone who sought opportunistic solutions to seemingly intractable social problems like hunger, infant mortality, illiteracy, and environmental degradation. Drayton and his associates traveled the globe seeking pioneers, then looked for ways to support them through grants, professional services, and joint ventures. He recalled his simple but audacious goal to David Bornstein, author of the recent How to Change the World: Social Entrepreneurs and the Power of New Ideas: “Was it possible to create a system that would, with high reliability, spot major pattern-changing ideas and first-class entrepreneurs before either were proven?” The answer was yes. With a current annual budget of thirty million dollars, Ashoka has supported more than two thousand fellows in over sixty countries.

If social entrepreneurship was a religion in search of a bible, the scripture came in 2004 when the Indian-born University of Michigan business professor C. K. Prahalad published a seminal book called The Fortune at the Bottom of the Pyramid: Eradicating Poverty Through Profits. Prahalad, who died in 2010, was brave enough to argue that Westerners needed to stop pitying the poor as victims and start respecting them as value-conscious consumers and even small-scale entrepreneurs. He defined the bottom of the economic pyramid as those earning less than two dollars a day—some four billion people worldwide. Obviously these poorest of the poor do not consume at the level of Westerners—their buying is overwhelmingly focused on needs, not wants, and impulse purchases are mostly on the level of snacks and trinkets like key chains—but their total spending power amounts to trillions of dollars. “This is not a market to be ignored,” wrote Prahalad. Indeed, even a casual visitor to all but the most destitute and autocratic third-world countries cannot help but be amazed by the vibrant local food and clothing markets—to say nothing of the roving snack and trinket sellers who ply traffic jams—where buying and selling takes place in environments of such unfettered chaos as to seem physically unsafe. And of course some Western corporations, like Coca-Cola, have done very well by selling to the world’s poor.

All of these observations suggest that the idea of poverty is highly relative and impossible to separate from context. In Ghana (as I was to learn), small-plot cocoa farmers and other cash-crop growers are in fact diligent savers. They often barter for daily needs, breaking into their cash hoard only when something they regard as extraordinarily desirable comes along. Put in business terms, their balance sheet is sterling. Such people certainly do not think of themselves as poor, especially when their own measurement of happiness is less contingent on material possessions and more heavily weighted toward the security and support of family and friends. These are the billions of Africans and Asians and Latin Americans who appear “poor” to us but in reality bear no resemblance to the belly-swollen refugees with outstretched hands that epitomize the Western image of the developing world’s population.

But from one village to the next can be night and day. Plenty of rural Ghanaians really are poor, even by their own standards, often desperately so, and in debt to boot. The point is, you can’t tell who is truly poor and who is not just by looking at them. And you certainly can’t tell by giving stuff away to them; who wouldn’t accept a free well or clinic? The only way you can tell who has money and who doesn’t is by offering to sell them something they want and need at an honest price.

By the time Gates gave his speech at Davos, backlash against conventional foreign aid was growing. In 2006, the year microlender Yunus won the Nobel Peace Prize, economist William Easterly published The White Man’s Burden: Why the West’s Efforts to Aid the Rest Have Done So Much Ill and So Little Good. As the title suggests, the book is a scathing polemic on the failure of governments and nonprofits (including Easterly’s former employer, the World Bank) to make any significant dent in the problems of the developing world. “The West spent $2.3 trillion on foreign aid over the past five decades and still has not managed to get twelve-cent medicines to children to prevent half of all malaria deaths,” he wrote, comparing this tragedy to the marketing push in the summer of 2005 that sold nine million copies of the sixth Harry Potter book in a single day. “It is heartbreaking that global society has evolved a highly efficient way to get entertainment to rich adults and children, while it can’t get twelve-cent medicine to dying poor children.”

According to Easterly, one problem is that well-meaning but clueless bureaucratic “Planners” have created a culture of freebies in the third world that makes it difficult for market forces to find a viable niche. When a charity gives away mosquito nets, what happens to the local entrepreneur who is trying to make and sell mosquito nets at a reasonable profit, running a business that employs villagers and sustains itself? Easterly compared the Planners to those whom he called “Searchers.” The Searchers are experimenters who don’t claim to have all the answers but are willing to hit the ground and find out—especially if it leads to some personal reward. “Searchers have better incentives and better results,” he wrote. “When a high willingness to pay for a thing coincides with low costs for that thing, Searchers will find a way to get it to the customer.”

It’s a compelling argument—but searching takes time. Gates himself recognized the challenge: “Sometimes market forces fail to make an impact in developing countries not because there’s no demand, or because money is lacking, but because we don’t spend enough time studying the needs and limits of that market.”

Which helps explain why so many market-based innovations for the developing world are large-scale corporate mobilizations. Gates mentioned the efforts of GlaxoSmithKline to develop affordable drugs; Prahalad wrote about Unilever’s success inventing a more effective way to iodize salt using molecular encapsulation, preventing mental retardation in Indian children while making money. These are multinational behemoths that can easily drop a few million into research and development with relatively little overall risk. Their developing-world missions are the corporate equivalent of the World Bank, or the Peace Corps—admirable business ventures, but hardly adventures. I was looking for the place where venture and adventure intersect. As I was about to learn, it was a dangerous crossroads with no traffic light.