Out of the plane and onto the molten tarmac of Kotoka Airport, you smell it right away. Africa has a smell as distinct as the subway of Manhattan or the eucalyptus of Laurel Canyon—pungent and exotic yet vaguely familiar, like burley pipe tobacco or pontifical incense.

“Welcome to Ghana,” said Whit as we walked through immigration, past a large sign warning that pedophiles were decidedly unwelcome here, and into the January glare of my first morning on the oldest continent. The previous afternoon we had met at JFK—he from Seattle, me from Maine, along with Harper—to connect to Accra. Whit had been in Ghana, laying the groundwork for Burro, from August to November of 2008, and Jan had been in charge since he left. So far the company consisted of Whit, Jan, Kevin, the Tata pickup, and a few thousand batteries. My plan was to spend the first month of 2009 there with my son (who had been given an independent study project on recording Ghanaian field music for his high school), during which time I would annoy Whit as much as possible, explore the country, and, if things worked out, prepare for a much longer stay later in the year.

Outside the terminal, a gang of aggressively friendly touts immediately surrounded our luggage cart, fighting for the opportunity to guide us to a taxi. “No, no, no thank you, we’re okay,” said Whit, but nobody listened or cared. The rule seemed to be that anyone with his hand touching any bag on the cart was entitled to a tip, so a dozen dreadlocked men with outstretched arms frantically huddled around us, tripping over one another, grasping at luggage and arguing as we pushed through the crowd, looking like a giant moving tarantula. “We’re waiting for someone,” said Whit. “We have a ride. No taxi. No thank you.” Harper, dazed with jet lag, wandered off to the snack stand and came back with two Red Bulls. One was already empty and he was working on the second. “He’s gonna come down hard,” said Whit. “Charlie!”

Across the parking lot, waving from the door of an older Mercedes-Benz, was a big, tall, athletic man with a wide smile. He was wearing gym clothes and shaking his head at the gang surrounding our overflowing luggage cart. “Hey, Whit! Sorry, I can’t get any closer.” Whit’s Ghanaian business partner waited for us outside the security cordon. We piloted the luggage cart and the attached porters in his direction. Charlie (not his real name) yelled at them in Twi and tossed some brightly colored bills. He hugged Whit. “Welcome back!”

“You still driving this old wreck?” said Whit.

“Who can afford a new car?” said Charlie. “We have not rented enough batteries yet. Besides, it holds a lot of baggage.”

It did, amazingly, and we were off to Koforidua on a Sunday afternoon.

I liked Charlie right away. Like many Ghanaians I would come to know, he was generous, sincere, and completely unflappable, relying on an endless taproot of humor to cope with the daily indignities of African life. Stopped at a red light in front of Ghana’s new presidential palace, a curvilinear metallic ziggurat that is meant to suggest a traditional Ghanaian chief’s throne (called a stool) but looks more like a rocket launch pad from the 1939 World’s Fair, Charlie stuck his arm out the window and gestured to a tall young woman selling bags of fried plantain chips from a bowl on top of her head. He quizzed her in Twi in what was obviously some form of mock indignation, and the two exchanged pleasant banter until the light changed and we sped off.

“What was that about?” asked Whit.

“I asked her why she is not in church today,” Charlie replied, laughing. The son of a Unilever executive who was a part-time minister, Charlie, fifty-six, inherited the preacher’s ardent voice if not his precise spiritual calling. Although like most Ghanaians he is among the faithful (and married to a devout Catholic, a minority religion in this former British colony), mostly Charlie proselytizes for business. His upbringing was middle class by American standards but relatively privileged for Africa. After attending Accra’s Achimota School, a boarding institution from the colonial era and one of the most prestigious secondary schools in Africa, he majored in biochemistry at Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, anticipating a medical career. But the physician’s life was not for him, and he went on to study timber management. Most of his business ventures have been in the building trades—manufacturing high-quality construction materials—and he owns several properties around Accra and farther to the east, in the Volta Region of his ancestry. Charlie is a member of the Ewe tribe; besides English he speaks Ewe, Twi, and Ga, which is Accra’s indigenous language.

“Look at this,” said Charlie, this time in English, gesturing over the hood as we idled at another red light.

In front of us, a truck carrying maybe thirty young men in its open cargo hold lumbered past, hiplife music blaring from speakers, the men dancing and waving red, white, and blue flags picturing an elephant and the letters NPP—the National Patriotic Party. “Let’s hope they are going home,” said Charlie as the music slowly faded and the truck disappeared into the heat, shimmering like a mirage. “Enough of this already.”

One month earlier, Ghana’s presidential election had been too close to call. The sitting president, John Kufuor of the NPP party, had served his two-term limit, and his potential successor, Nana Akufo-Addo, was running against John Atta Mills of the opposition National Democratic Congress (NDC). The dead heat had forced a runoff just a few days before our arrival, and Mills, a fifty-six-year-old lawyer and university lecturer with a gap-toothed smile that made him look like a black David Letterman, won. But in Africa, elections are never over when they’re over. While most Ghanaians were expressing pride that the country could now count two consecutive democratic transitions to opposition parties (a record for postcolonial Africa), plenty of NPP loyalists were still agitating, claiming the election was rigged, a challenge for any party not in power, to be sure. (Observers from the Carter Center said it was largely free and fair.)

Swirling under the surface was an undercurrent of ethnic animosity. Ghana has taken measures to ensure that its political parties are not tied closely to ethnic groups. National parties must have viable offices in every region, and parties may not include ethnic names or symbols in their regalia. Nevertheless, the NPP stronghold is the central Ashanti tribal region, while the NDC was founded by a member of the Ewe tribe—the former military head of state, Flight Lieutenant Jerry John Rawlings.* Although Mills is not Ewe, he was Rawlings’s vice president. And Rawlings—who sent three former dictators and five generals to a firing squad in June of 1979—was still very much on the scene, speechifying and prognosticating. Further stirring the pot was the country’s partisan tabloid press, which regularly ran block-type headlines proclaiming NDC THUGS RAID NPP RUMPUS OR NPP PLOTS NDC MAYHEM.

Compared to many African countries, tribal tension in Ghana burns at a very low flame; it rarely rises above the level of ethnic humor. Any serious tribal conflict seemed unthinkable, but the election did seem to be bringing out the worst in people, and some of the roving bands of political supporters acted more like street gangs cruising for a fight. These were not gangs you would want to engage in political debate.

“So what happens next, Charlie?” Whit asked. He had been home in Seattle for six weeks over the holidays, following the Ghanaian election on the Internet, and he was anxious to catch up on the ground.

“I think things will be okay,” Charlie said. “People are starting to calm down. But right now the problem is that Nana has not conceded. He needs to get up and say that.”

We were heading out of town on the main road north toward Koforidua, two and a half hours away. Whit had chosen the town for his test branch because it was within a day’s round-trip drive to the air and shopping hub of Accra yet far enough away to be out of the limelight. As our car switched back and forth up the Akwapim Ridge, Charlie pushed the accelerator to the floor and passed a banana truck on a blind curve. This was not a lightly traveled road; I estimated the chance of an oncoming vehicle to be high, perhaps once every few seconds. I closed my eyes, and when I opened them I noticed other cars doing the same thing, going both ways, as if it were completely normal to risk an explosive, dismembering head-on collision to gain a relatively small time advantage on a Sunday afternoon. Harper, who had just finished driver’s ed back in Maine, gave me a wide-eyed look. “Don’t try this at home,” I said.

We climbed higher, dodging trucks and taxis. Soon Accra and the Gulf of Guinea spread out below us, felted in dust and smoke. Along the highway, fields had been set ablaze by farmers clearing underbrush before planting. Adding to the haze were street vendors, who fanned flaming charcoal fires below rice pots and shards of sizzling cocoyam and plantain.

“Dad, they’re selling dope all along this road,” Harper said to me in a whisper, apparently not wanting Charlie and Whit, in the front seat, to know that he was onto an incredible scam.

“What?”

“Dope. Pot. Mar-i-juana. I can smell it. These guys are dope dealers, and they’re burning samples.”

“They’re not selling dope,” I said dismissively, ignoring for the moment how he knew what dope smelled like. “And even if they were, why would they be burning samples? This is not Jamaica.”

“Rita Marley lives up on this ridge,” said Whit on cue, playing tour guide, ignorant of our conversation in the backseat.

“That’s right,” said Charlie.

Okay, maybe they were selling dope. Maybe the free samples were some native Ghanaian version of creative capitalism. But no, it didn’t smell quite like dope. Then I placed it. The smell of Ghana was the smell of burning leaves from my childhood, a time before anybody cared about mulching or recycling or even air pollution, when leaf piles were set ablaze at the curb every fall. The burning fields and the charcoal fires smelled the same. In my youth the cities and suburbs of America were regularly on fire, and autumn was delirious and orange and black with smoke. I was ten in the summer of 1967 when Detroit was in flames during the race riots, and it seemed perfectly normal to me, just a little early. Africa is still on fire.

“How did you guys meet?” I asked.

“Serendipity,” said Whit. “We met last May in Accra. I was still just kind of noodling the whole Burro idea back in Seattle, and I found out there was a World Bank conference called ‘Lighting Africa’ in Accra. I thought that was a perfect excuse to come over, do some initial market research, and scope out possible partners.”

“Why did you want a partner?”

“Well, it certainly makes things easier. You can be one hundred percent foreign-owned in Ghana, but it’s a bit tricky. I really wanted someone on the ground who knows the terrain. Anyway, I had arranged a meeting with this guy who heads up the Ghanaian branch of a U.S. NGO that helps jump-start small- and medium-scale business enterprises in developing countries. They do the largest annual business-plan competition in Ghana, so I wanted to meet with them to get the lay of the land. In the back of my mind I thought maybe they would be a sponsor, and maybe they would know whom I should talk to as a potential partner.

“So on the day of our meeting, the guy got called away on an emergency and he arranged for me to meet with another person from his group, a very smart woman named Afi. We met, and I could tell she was pretty excited about my idea. They hear all kinds of bullshit stories over here, and they’ve been through the wringer with snake-oil Western no-ops coming over. Charlie’s been screwed by these types in the past. So Afi was definitely sizing me up. I could tell we were connecting, and she was figuring this guy seems real and has integrity.

“She told me she knew a lot of potential partners. ‘Let me think about it and get back to you,’ she said. The next day she called and said she had a guy she wanted me to meet. So we all met at the Golden Tulip Hotel—me, Charlie, and Afi. Charlie and I hit it off right away. I was very impressed with his entrepreneurial background; he had tried a lot of things. I could tell he was passionate about creating things that make a difference while making money at it. And because of his forestry and construction background, he loves managing work in the field; he doesn’t want to sit in an office like a lot of Ghanaian businessmen.”

Charlie laughed. “Offices are so boring.”

“Well, about fifteen minutes into that meeting, Afi dropped the bombshell that Charlie was her husband.”

Charlie laughed harder. “She didn’t want that to influence anything.”

“Afi did say she knew a couple of other people as well, but my time was short and I felt great about Charlie, I felt this could work. So it wasn’t the most rigorous executive search in the world, but I think it turned out really well.”

“You could do a lot worse,” said Charlie.

“No shit. I could have gotten a total operator who’s just a crook, some flashy guy tooling around in a Mercedes—”

“What are you saying? I drive a Mercedes.”

“I meant a late-model Mercedes, the kind with air bags and a CD player.”

“Oh you are bad!”

Just when I thought that our luck in overtaking large vehicles up steep hills must surely run out, the gods took pity on us and we pulled into the traffic of downtown Koforidua, where passing became impossible even by the relaxed standards of Africa.

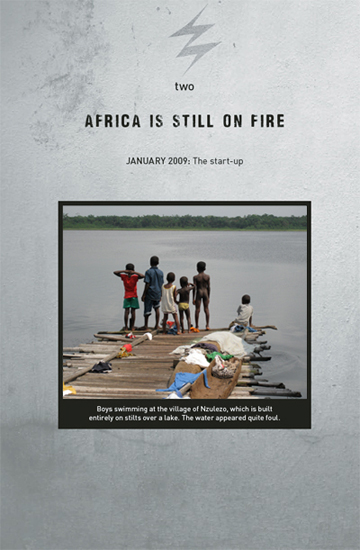

Ghana is a country of striking beauty, roughly the size of the United Kingdom yet considerably more diverse in climate and landscape. The lower third of the country is dominated by verdant rain forests teeming with neon-colored birds and orchestrated by the treetop chatter of the white-tailed colobus monkey. Along riptide-laced Atlantic beaches, hundred-foot-tall coconut palms (in their prime natural habitat) hover like extraterrestrials over raffia huts where fishermen tend their nets in brightly painted dugout canoes. Colonial-era rubber and palm plantations march along the coast road, which winds through beachfront villages huddled below the whitewashed parapets of slave castles—the oldest European buildings in sub-Saharan Africa, illogically bright and romantic, the kind of places that in the West would be converted into boutique hotels with horizon pools and mojito bars, but in Africa crumble inexorably, like decaying teeth. In the north, the rain forest gives way to drier savannah, and villages far off the missionary track are clustered around medieval mud-and-stick mosques—pincushion palaces with the uninhibited creative charm of a child’s sand castle. Herds of migratory elephants, hippos, and waterbucks roam vast reserves that are barely accessible and (unlike the travel-magazine game parks of Tanzania or Botswana) virtually un-touristed. Way up near the Burkina Faso border are communal lodges painted in striking geometric patterns, sacred colonies of giant hammer bats, and strange tribes where women still wear “lip plugs”—six-inch wooden discs inserted (one can only imagine painfully) in distended, pierced lips to create the effect of grotesque cartoon duck bills. The east of the country is defined by claw-shaped Lake Volta, the largest man-made lake in the world (created in the 1960s by the Akosombo Dam, which powered my brother’s battery chargers), where moldering steamers straight out of The African Queen chug hesitantly between forgotten outposts with pulp-novel names like Kpando and Yeji, and waterfalls sluice down jungle escarpments.

Koforidua is not one of these places. Koforidua—population roughly one hundred thousand, the same as Gary, Indiana, which could well be its sister city—is the kind of place that guidebooks euphemistically refer to as “a good jumping-off point” or “a decent enough base for exploring the wider region.” In other words, “the bus turns around at this backwater, so we are obliged to tell you something about it.” Perhaps it is unfair to say that Koforidua is to Accra what Gary is to Chicago. It is, in fact, the capital of the misnamed Eastern Region (the Volta Region lies farther east). In Europe, Koforidua would be the kind of busy small city, like Tours or Sheffield, that offered a range of hotels and restaurants to suit any budget, plenty of public transportation, and convenient access to nearby tourist attractions. But Kof-town (as it is called), while undeniably busy, is not in Europe. It offers no nearby tourist attractions save a couple of admittedly decent waterfalls and a weekly bead market of regional and, arguably, even international importance so far as handmade beads go; it boasts only three substantial restaurants, serving related pathologies of the same brown food; and it lays claim to just a few overpriced hotels inconveniently located several miles outside of town.

Hotels, at least, were not our issue. We had a home. Of sorts.

My brother’s rented quarters, which tripled as residence, Burro corporate office, and its first pilot field branch, occupied the entire second floor of a two-story colonial-era municipal building on a busy downtown street called Hospital Road. (The local hospital, may God have mercy on your soul, was indeed a short walk east.) The first floor accommodated a grocery store the size of a bus shelter and—taking up the remaining fifty feet or so of street frontage—a cluttered electronics concern, open until well after midnight, that mostly trafficked in gargantuan secondhand sound systems powerful enough to shake paint off the walls.

With the entire street façade devoted to commerce, entrance to Whit’s flat was through a paved rear courtyard shared by another block of buildings behind us. This communal outdoor living space served as a playground, laundry room, kitchen, and bathroom for perhaps a dozen large families. Along one side of the courtyard ran an open concrete sewer, perhaps eighteen inches deep and as wide, through which coursed a slow-moving stream of soapy gray effluvia and floating trash. While genuine sewage of the toilet-flushing variety did not appear to drain into this fetid trough, my brother’s kitchen and bathroom sinks could be plainly traced as tributaries, from drainpipes running down the side of the building. At any rate, the sewer’s status as a conduit of relatively innocuous sink water was undermined by the fact that most of the courtyard’s residents—men and women alike—freely peed into it. At least one uninhibited child regularly emptied his bowels into the babbling slipstream. The courtyard itself was sloped so rainwater would roll into the trench—along with every child’s ball and other toys, which then got picked out, occasionally washed, and put into play again. In short it was a pathologist’s nightmare, and a perfect example of why diarrhea is endemic to children in Africa.

At the rear of the courtyard, a double flight of red-painted concrete steps led up to my brother’s flat. The door opened to a long perpendicular hallway off which two main rooms faced a colonnaded veranda, accessed through French doors, above the street. In the first room, makeshift wooden tables were covered with batteries, chargers, and extension cords, over which an industrial-sized metal fan throbbed loudly in a vain effort to keep the electronics cool. The other main room, larger, had a dining room table and chairs, and walls plastered with regional maps and whiteboards listing agent names and rental volumes. At either end of the hallway was a pair of smaller rooms, one front and one back. The back room on the west side was Whit’s bedroom; the street-facing room adjoining it was the Burro office, with two desks, bookshelves, and a massive built-in safe with a keyed lock that no one could open and contents, if any, that remained a tantalizing mystery. The office could be accessed from Whit’s room or the veranda. Over on the opposite side, the rear bedroom was occupied by Jan, and the front room, also accessible from either Jan’s room or the veranda, was to be Harper’s and mine. Behind Jan’s bedroom, forming a sort of ell, was the small kitchen (sink, narrow fridge, Lilliputian four-burner gas stove) and a shower room, toilet cabin (with a commercial jet–siphon flushing action that I came to appreciate after a few meals at the local dives), and separate bathroom sink.

These cooking and ablution facilities, while Spartan by North American standards, were in fact pharaonic according to the dim expectations of Africa—particularly the keg-sized hot water heater above the shower, which apparently had no temperature setting cooler than scald. (Months later, Whit found the thermostat.) By contrast the kitchen sink provided only cold water, so dishwashing was accomplished by transferring a bucket of hot shower spray into the kitchen sink. Having running water at all was a minor engineering miracle: the murky public supply ran only twice a week, so at great expense Whit had installed a pair of 1,800-liter plastic tanks on the roof, creating a 950-gallon reservoir. In theory these backup tanks would fill when the utility gods deigned to open the communal spigots; after the town water went dry, we would subsist on this bacterial oasis cleverly cached on our roof. (Less fortunate residents of the block got by on dry days by hauling water from a large communal cistern located in another courtyard behind ours. When that ran dry, they had to buy water, per bucket, from a vendor across the street.) In practice, however, with a full house including one American teenager who showered twice a day, we ran out of water often, so the normally routine act of turning on a faucet was freighted with suspense; you never knew if you would get water (or what color it would be), a blast of pressurized air, or a pathetic burp followed by nothing.

I had to commend my brother for putting up with these inconveniences; I can’t picture a lot of multimillionaire middle-aged American businessmen voluntarily living this way, particularly those happily married with a family eight thousand miles away. I regarded it as testament to his entrepreneurial commitment. In fact, he admitted, he would have gladly put up with even more straitened arrangements had he not been worried that Jan, who made no demands but also lived comfortably in the Northwest, might run out of enthusiasm for cold bucket showers. At any rate, the place was actually rather charming and comfortable in a rakish, retro way. It was clearly built at a time when the Brits were doing things right, with high ceilings, lots of cross ventilation, and hand-carved mahogany doors and transom windows. The building had originally been the regional office of the British American Tobacco Company; later it was the office of the state labor department, and it was still known to locals as “Old Labor.”

When Whit came into town looking for digs, the real estate agent drove him around to look at villas on the outskirts, down dark rutted roads and behind high walls. But that would never work for a business that was going to need a visible presence in the city. “I was like, ‘Dude, you don’t get it,’” Whit told me. “‘We want to be in town—right in town.’ The agent said, ‘Oh, there is no place suitable for obrunis in town.’ I said, ‘Try me.’”

The place was cheap—two hundred cedis a month, payable in advance for two years (typical for Ghana), which came to about three thousand dollars. But it wasn’t exactly in move-in condition. “Oh man, this place was three inches thick in dust when we first saw it,” said Whit. “The kitchen had no appliances, no counters or cabinets—just a sink hanging in midair from pipes. The toilet was there, I just had to replace the seat.”

“What was wrong with the existing seat?”

“It was there.”

Some problems ran deeper. Above the coffered plywood ceiling was a corrugated metal roof dulled by rust and thus incapable of reflecting the relentless tropical sun. With no insulation of any kind, the roof was a heat sink. So, despite ceiling fans in every room and huge louvered-glass jalousie windows, the flat was transformed into a living hell roughly fifteen minutes after sunrise every day. Closing windows was unthinkable; in that stifling cloister, the slightest breeze was greeted like an apparition of Our Lady of Guadalupe. As a result, the flat was so noisy—horns, roosters, music, screaming children, and motorcycles—that you had to stick a finger in your ear to talk on a cell phone. This was indoors. Out on the veranda, otherwise a lovely vantage point above the street commerce—young men splitting coconuts with machetes, women selling sliced papaya snacks in front of plywood stalls hawking used brassieres (something about the coconuts and the brassieres suggested a small-time burlesque routine)—conversation transpired at a yell. Although we could and often did cook our own dinners from provisions gathered at the town’s huge outdoor market, at the end of many days all we wanted was to go somewhere that had not been baking under a tin roof since six in the morning. Usually, that was the Linda Dor restaurant.

As Whit had predicted, Harper was down for the count by sunset; while he slept off his Red Bull bender, Whit and I ambled out for dinner at the Linda Dor, a few blocks down Hospital Road. “Watch every step you take, and don’t ever stop watching,” he said as we shuffled down the dark road, jumping over open sewers and dodging the jagged metal stumps of former signposts. “There is no concept of liability in Africa, and no one to blame if you fall into something. Also, I can pretty much guarantee that your medevac coverage won’t airlift you to Germany for a twenty-inch gash in your leg; you’ll be stuck with the local clinic, followed by a very unpleasant ride home on that shitty Delta plane. Or you could fork over four grand for a first-class seat.”

Like our living quarters, the Linda Dor possessed a faded colonial charm. It had certainly seen better days, and its dingy décor and dark recesses suggested that there was much concerning this establishment that you really didn’t want to know about, at least not before dinner.

We sat near the door and I opened the menu warily. Much to my surprise, laid out across its greasy pages was the promise of an intercontinental repast without equal. Steak frites, pasta Bolognese, boeuf Bourguignon, and Chinese stir-fry, not to mention African delights like peanut stew and the ubiquitous fufu, were all possible. Years of living in New York had trained me to be suspicious of restaurants that “specialize” in more than one ethnic approach; purveyors boasting simultaneous expertise in Korean and Mexican were not likely to create edible versions of either. But the menu at Linda Dor took multicultural cuisine into bold new territory. Clearly, behind the stove of this unassuming chow house reigned a polyglot chef of global ambition, a Baedeker of the broiler.

“What do you recommend?” I asked Whit.

“Nothing. But don’t worry, they won’t actually have any of this stuff—well, maybe one Chinese dish, but it won’t be anything like Chinese food you’ve ever seen. I’d stick with the Jolof rice.”

Rube that I was, I had not yet learned that in Ghana, restaurant menus are merely aspirational. Any given establishment, no matter how remote, may boast on its menu anything from Castilian tapas, Lebanese mezze, Auvergnian biftek, and Venetian fritto misto, none of which has ever been prepared within two thousand miles of the place, even if the ingredients were available. A request for any of these exotic belt-stretchers is invariably met with the response “It’s finished.”

Looking over the pages devoted to reliably available local fare, I saw something even more curious. “What’s grasscutter?” I asked Whit.

“Rat. Well, a ratlike rodent. They eat regular rats here too, but grasscutter is big—bigger than a rabbit but with a ratlike tail. Maybe like a muskrat. Lives in the tall grass. It’s a delicacy. Men hunt them with shotguns and sell them by the side of the road for extra cash.”

It turns out that the grasscutter market is the subject of ecological controversy because hunters typically flush out the animals by setting grasslands on fire, contributing to the alarming deforestation of West Africa. Reckoning that one sample of the tender viand (in the interest of journalism) was unlikely to raze the African savannah, I pressed ahead bravely: “I’ll have the grasscutter stew with fufu, please.”

“Fufu is finished,” the waitress replied meekly. “We have banku.”

Whit explained that banku is a fermented version of fufu. I consented. He ordered the Jolof rice.

“Is the food better in the former French colonies?” I asked Whit.

“Considerably.”

“So why are we here?”

He shot me a weary look. “Well as much as I like good food, there were some other considerations, some of them obvious, others not. Before last summer I had never been to Ghana, although I came close on New Year’s Eve of 1981. I was in a bush taxi at the border in Burkina Faso, which was still called Upper Volta. That was the night of the second, and successful, J. J. Rawlings coup, when they sealed the borders.”

“Whit, you were in the CIA. You let a closed border stop you?”

“Only that one time, and only because I left my decoder pen and shoe phone at the hotel. So I always felt kinda ripped off, like my Ghana trip had been taken away from me somehow. For years I toted around my unused Ghana visa as a shameful badge of travel curtailed. But since then, Ghana has gone through a pretty phenomenal evolution. There’s a very free press; in fact the press is rated freer than in some of the Eastern European countries. There are very strong democratic institutions, albeit still fragile at times, as we are learning in the election just finished. But the country has now had five presidential elections, at least the latter three of which were widely acclaimed as substantially free, fair, and transparent. The first one, when Rawlings won in ’92, was rigged, but the second one, in ’96, was much more fair, and they have been since then.”

My stew arrived, bony chunks of skin-on grasscutter in a thick brown slurry. On the side were two softball-sized gray dumplings—the banku. Whit explained that traditionally one eats the banku (or fufu) by hand, small pieces dipped in the soup like a doughnut in coffee. It is also considered rude to actually chew it, which, upon tasting the gelatinous paste, did not seem much of a sacrifice. “Go ahead and eat,” said Whit a bit too forcefully, as if addressing a reluctant child staring at his vegetables. “There’s no telling when mine will come. Ghana has no traditional restaurant culture; they just bring food out whenever it’s ready.” I nodded and tucked in to my rat, which, as I had hoped, tasted much like rabbit.

“So you’ve got strong democratic institutions, and a strong civil society as well,” Whit continued. “There are a lot of professional organizations and associations and church groups that really push for a better society and are working in various ways to improve things. And it’s a relatively well-educated society. Ghana used to have the best education system in Africa; it’s probably suffered in the last twenty years. It’s also got a history of a monetized rural economy, so that was very important. You go to some countries, like Ethiopia, and the rural economy is very much at the subsistence level, maybe with some barter. Here there’s a long history of cash-cropping and monetization, so people are used to earning money in a wide variety of ways and living in a cash economy.”

This commercial bent seems ingrained in the Ghanaian culture, a legacy of the country’s rich gold mines—the region’s most valuable natural resource before the transatlantic slave trade, and still the second most important export after cocoa. The Brits of course called Ghana the Gold Coast; under their rule, Ashanti tribal leaders were groomed as business partners, a transformation that accelerated in the early twentieth century. In 1930 one of them, Kofi Sraha, described the situation in terms that would sound familiar to the most acquisitive baby boomer: “We turned ourselves from Warriors into Merchants, Traders, Christians and men of properties, [kept] moneys in the Banks under British Protection and began to build huge houses.” It was easy to see Whit’s Ghanaian partner Charlie as the modern descendant of this legacy.

A loud crack ricocheted inside my skull, and pain I had never felt outside of the dentist’s chair bored through a maxillary molar. I reached inside my mouth and extracted a mangled shotgun pellet. “Fuck, look at that.”

“Holy shit,” said Whit. “I knew there was a reason I never eat the grasscutter. Chew carefully.” Indeed; by the end of the meal I had extracted five pellets. (I later learned from Charlie that you want your grasscutter to have pellets. “That proves they were properly shot, and not killed with rat poison,” he said.) Whit’s rice arrived just as I was finishing up.

“Ghana is a beautiful country too,” Whit continued. “That’s also important because I’m trying to attract and retain American and other partners as we grow. And obviously the English language here helps with that as well. The business climate is also very friendly to foreign investment. There’s guaranteed repatriation of profits, albeit with an eight percent dividend tax. So you’ve got a very positive and improving business climate for outside investors. Put all those factors together and it just makes sense.”

It was late, still quite hot. Jet lag was winning. I paid the check, gathered up my shotgun pellets, and we left for home. “Let’s take the scenic route,” said Whit. “I’ll show you a bit of the town.”

We tramped down gloomy side streets, where African men leaned against sheds, sharpening machetes along smooth stones and eyeing us with curiosity. I briefly weighed the relative benefits of getting hacked up by a sharp versus a dull machete, deciding the difference would be largely esoteric in the moment. White people are a rare sight in Koforidua, and it felt strange to be such a visible minority. For the first time in my life I felt some visceral awareness of what it must be like to be black in a largely white society, to be stared at like a freak. I wasn’t sure if our route was prudent; these were not streets I would walk down at night in, say, Detroit. But we weren’t in Detroit, and it was fine. Whit said “Good evening!” to everyone we passed, and the sullen faces would suddenly beam. My dopey kid brother was at home here, and I was glad to be with him.