When I told my African friends that I wanted to spend time living and farming in the remote, off-grid villages where Burro was doing business, they responded with polite laughter. When I convinced them I was serious, they reacted as if I were proposing missionary work in a leper colony.

“That is a very hard place to live,” cautioned Kevin. “No toilet facilities, no water, the food is very different from what you see in town; you will surely get sick. And the work is very hard. I am not sure you will like it.”

“It isn’t really about liking it,” I replied, sensing a bit of projection on his part. Kevin is in a small minority of Ghanaian men who might be called husky—not grossly obese, but a long way from six-pack abs; it would be hard to picture him scampering up a coconut tree with a machete. “It’s more of a learning process,” I added.

It was the summer of 2009; Whit was still in China talking to manufacturers. The new pay-as-you-go deposit system was proving a big hit in the new Krobo territories. Jan, Kevin, Rose, and Adam could barely keep up with growth. More batteries were on order. With Whit returning in a month, it seemed like a good time for me to get out of the stifling city and learn more about village life than you could glean in a one-hour gong-gong.

“In the rainy season?” said Charlie. “What you will learn is the meaning of a nightmare!” He went on to stress that—in the right season, of course—he too would love to get back to his “roots” with a village stay. It would be difficult to imagine Charlie thriving without the restaurants and international shops of Accra, or the fresh-baked bread delivered daily to his home. But put him in a small African village of mud huts and cook fires and he waxed as pastoral as a Hudson River School painter. “Ah, you can really breathe out here!” he would say whenever we traveled to a Burro village. “And the people are so real, so friendly. This is surely the life for me.”

With his worldly wisecracks and flirtatious humor, Charlie was an exotic urban sophisticate to these simple villagers. But at least he was Ghanaian. I, on the other hand, was a space alien. “We can receive you,” was the stiff reply from an agent for the village of Adenya named Ebenezer Yirenkyi Kissiedu—a former civil servant turned farmer. “But we are human.”

I think he meant human in the Paleolithic sense—Homo sapiens at his most essential. “We have no light,” he continued grimly, “and in the night there are small ants which will bite you and leave black spots all over your body. Then the mosquitoes will come, and you will get malaria.” His use of the nonconditional tense suggested this was an inarguable certainty, like a biblical plague on the pharaoh.

To all of these concerns I was tempted to reply, “No worries, I’ve been camping lots of times.” But equating their given lot of grinding survival to an enchanting frolic in a national park seemed to trivialize their very existence, and I couldn’t find the words. What would you say? “Yes, when I grow exhausted from a week of staring at my computer screen, and the Red Sox are playing some shitty National League team and there are no good movies and the restaurants are crawling with tourists, I love to get away from it all and recharge with a weekend in the mountains. This should be cracking good fun! Lawn darts, anyone?”

Instead I fell back on a more estimable chapter of my biography: “I used to have a farm in America.”

Ebenezer looked at me like I was a pair of Siamese twins. “It must have been a mechanized farm, no?”—spitting out mechanized like an epithet.

“No. I worked it by hand,” I replied, forgetting for the moment that once a year I did hire a local guy to come over with his tractor and till my larger plots. But mostly it was backbreaking hand labor. Still, I didn’t add that it was a “hobby farm” and my survival never depended on it.

“You have boots and a cutlass?” he asked, using the local term for a machete.

“I do.”

He seemed a bit more convinced that I might survive a brief sojourn in the bush, but you couldn’t say he was anxious to secure the arrangements.

Jonas Avademe, on the other hand, was practically falling over himself to arrange my visit to his village. So it was that I found myself one afternoon behind the wheel of the Tata, dodging craters on a washed-out dirt track to the distant village of Otareso, population 144 according to the recent census. (In Ghana, census data only counts adults of voting age; Jonas said that children probably brought the total number up to about 200.)

The sole written historical record for Otareso is penned in Jonas’s hand on a sheet of ruled school notebook paper, which he keeps in his mud-walled hut. It reads:

Otareso is a village located in the Akuapim-North District. It is said to have been established in the 1930s. The name of this village was named after a stream called “Otare.”

The origin of the people in this village are said to have come from Abiriw-Akuapem, led by Mr. Kwabena Botswe. Later, Mr. Christian Mensa Tugbenyo from Agorvee in the Volta Region, led a group of Ewes who also settled in the village.

Their main purpose of settlement was to tap palm wine and to distilled [sic] into alcohol as well as farming activities.

And not much has changed since then. “I am very proud in my village,” said Jonas in his pidgin English after I had transcribed the history into my notes. Whether he meant he was proud of his village or that his village is proud of him I cannot say, but both are plainly true. At forty-one (broad-faced, fair-skinned, medium build, with thin mustache and goatee) Jonas is hardly an elder—there are many older men and women in the village, including his own parents—but he is a respected leader and a diligent promoter of his community. He is also a lay leader in his local church, a parish of the Apostles’ Revelation Society—a seventy-year-old Ghanaian institution with its roots in the Ewe tribal region of Lake Volta. This is the same faith in which Charlie’s father preached.

Jonas’s local stature was enhanced in 2008 when he won the title Farmer of the Year for his district, competing against hundreds of other men in dozens of villages. The award is prestigious but also remunerative. This is what he won:

![]() five cutlasses

five cutlasses

![]() two bars of soap

two bars of soap

![]() one pair of rubber boots

one pair of rubber boots

![]() a polytank for storing water

a polytank for storing water

![]() a knapsack

a knapsack

![]() a backpack pump sprayer

a backpack pump sprayer

![]() some cloth

some cloth

![]() a six-battery tape player and radio

a six-battery tape player and radio

![]() a bicycle

a bicycle

![]() a certificate

a certificate

The award was based on productivity per acre, and after spending a few days with Jonas it was easy to see why he was a good farmer. The man was almost artisanally obsessed with detail, attentive to the point of fussiness. As he sat around his family compound before a meal, his eyes never stopped moving. While speaking to me in English he would stop mid-sentence and issue a stern observation in Ewe that caused family members to scramble in response—rearranging a wooden table, moving a lantern, fetching a pan of water, sweeping the dirt floor—in short, keeping the jungle feng shui of Jonas in order. This is an unusual trait in Ghanaians, who generally take a relaxed approach to life even when they are working very hard.

For his farm, Jonas maintained detailed rainfall records (“I have all the patterns,” he said). He worked with an adviser from the government agricultural station, who helped him learn green-manure techniques such as alternating soil-depleting crops like corn with nitrogen-fixing legumes like cowpeas. (Although green-manure practice is a cornerstone of organic farming, Jonas, like virtually all Ghanaian farmers, also used chemical fertilizers, pesticides, and herbicides.) He laid out string lines and planted his corn in perfect three-foot rows for maximum production, as opposed to simply scattering the seeds. (Other Ghanaians plant in rows too, but Jonas was the first in his village.) And he shared his knowledge with the whole community in a small demonstration garden he planted to teach other farmers.

On my arrival, Jonas led me on a tour of his land. We walked down a footpath through a plantain orchard, broad leaves bending in the breeze above thick green clusters of the large fruit, until the landscape opened to long, dramatic views across the corn to the distant heights of the Akwapim Ridge, ten miles away. There, high above the cultivated plots of the villages, sprawled the gated villas owned by the Big Men—the important government and business elites of Accra who kept weekend homes in the cool elevations. In the dry season of winter, the dust and haze obscured the ridge completely, but in summer the rains cleared the air and lifted the veil, and the poor farmers and the rich city men looked out on each other every day. Fast-moving thunderheads tacked like sailboats above the ridge, slicing shadows across the whitewashed mansions.

Jonas, who had only an elementary school education, did not envy the ridge dwellers. “I am very happy,” he said. “If I had gone on to second cycle,” the term for post-elementary school, “I would not be in this village; I would be working in an office somewhere.” He paused, then added, “Everything God does is good.”

Jonas’s father, a wiry little man with a crinkled brow, a silver Hitler mustache, and several missing fingers, emigrated from Benin; his mother is an Ewe from Ghana’s Volta Region. Jonas speaks Ewe first but also Twi, Ga, French, and English. “I can hear several more African languages,” he adds, meaning he can understand them but not speak in return. It turns out that many of the citizens of Otareso are from Benin and Togo—the pair of geographically narrow and politically fragile francophone countries east of Ghana—which explains why several residents (but not Jonas) smoked cigarettes, a distinctly foreign custom in Ghana.

Jonas farmed eleven acres outside of town, land on which his grandparents once lived. Their family compound—two tiny one-room houses, a cooking hut, a storage hut, and a bamboo corn crib—now belonged to Jonas; he called this place his cottage, distinct from his home in the village center, a five-minute walk away. His grandparents were tenant farmers, paying forty cedis a year in rent to a landowner; after they died, the owner offered the land for sale, and Jonas bought it in the year 2000, for sixty cedis per acre. It was a smart move: today, said Jonas, farmland like this along a road—as opposed to far back in the bush, where transport is difficult—sells for five hundred cedis an acre, when you can even find it. “Many more people are farming today than when I started twenty years ago,” he said, in part because people like his neighbors have emigrated from Togo and Benin, lured by Ghana’s stronger economy and greater freedom.

As we walked, Jonas identified trees and plants along the trail. There was odum, a hard red wood for making furniture, and ktsensen, a more common tree with white wood used for planks and scaffolding. Achampo is a medicinal herb that looks something like basil and is sold in bunches in the Koforidua market. “If you wound yourself with the cutlass,” said Jonas, “you rub the leaves in your hand with some water to make a paste, then you put it on the cut and tie it. It will heal more quickly.” We passed under a moringa, the wide, drought-resistant tree whose dime-sized leaves contain complete proteins and have saved Africans and their livestock from starvation when crops fail. “Also very good medicine,” said Jonas. “It cures ninety-nine diseases.”

We stopped to pick and eat large red berries from the asoa tree—“sweeter than sugar,” said Jonas, and he was right. He pointed out the four varieties of plantain trees on his land: apim, meaning “thousands,” yields a lot of plantains; sawmynsa produces three bunches; sawunu yields two very big bunches; and lowly pentu translates into “doesn’t give much.”

Sometimes his meaning got lost in pronunciation. “This tree is called ofram,” he said. “We use the wood to make the stew.”

“You make stew from wood?”

“Yes, is very nice for that.”

“It must be very soft wood.”

“Soft? No! Is quite hard!”

“You must have to cook it for a long time.”

“Pardon?”

“In the stew.”

“Stools.”

“Stools! You have hard stools from eating the wood. You should eat more mangoes.”

“No, no! We don’t make the feces. We make the stool—how do you say?—throne for the village chief out of this wood.”

And so it went, until we had returned to his cottage and he introduced his wife, Gifty, a shy and quiet younger woman who spoke neither English nor French, bent over sweeping the dirt courtyard with a whisk despite having lost her baby—and nearly her own life—a month earlier. Jan had told me that Jonas’s wife ran the village shop, so I inquired, through Jonas, how things were going at the store. “Oh no,” said Jonas, “my other wife runs the store.” My surprise must have been evident; polygamy is uncommon in the Christian parts of Ghana, although keeping a mistress is considered perfectly normal—what Ghanaians call tending the farm and the garden. “I will explain it all later,” said Jonas. “But now is time to help with building our neighbor’s house.”

It was Monday, which is rest day in Otareso—meaning it is taboo to farm. Friday is also a rest day, and Sunday is reserved for church, so actual farming only happens on four days. The taboo against farming on rest day is taken seriously. “If you are caught farming against the taboo,” said Jonas grimly, “you must pay seven rams to the elders.” (Otareso has no chief.) Upon closer questioning he acknowledged that the ram tax is more tradition than modern reality, but he insisted that no one farms on Monday or Friday.

That is not to say that rest day means no work. People have to eat, which means the women still have to cook. And men devote their rest day to communal activities. Today’s job was building a new house for a recently arrived Beninois family. The house had been framed with lengths of dried bamboo, split in half with machetes and nailed crosswise in a grid pattern between thick timber corners and door posts. The walls were being raised in mud—plain, red mud from a pit dug behind the house and filled with water from buckets and rain. I pulled on my Italian-made rubber farm boots (twelve cedis in the Koforidua market)* and took my place inside one of the rooms, where workers had piled a small Kilimanjaro of mud and were scooping handfuls into the spaces between the bamboo cross members. “You take it and push down, like this, between the wood,” said the Beninois man next to me in French, ramming a slab of mud into the wall. “If you see an air space, take like this and throw it in, comme ça”—and he demonstrated by hurling a mud pie into a cavity at close range. This was work that any kindergartner would love, and the men—it was only men—were having a grand time, laughing and shouting while getting covered with muck and sliding around the floor like hockey players.

Most of the men worked shirtless, and they all had biceps like steam-engine pistons, and chests that could have been carved out of onyx. Fourteen-year-old boys looked like young Cassius Clay. Here was an entire village of big musclemen who had never done any “exercise” in their lives.

The last step of the day’s work was texturing the walls by running our fingertips all over the wet mud to make deep grooves. After the mud dried, the grooves would hold the plaster, which was the final step before painting. (Homes are generally plastered smooth, inside and out, then painted; lesser shelters like storage rooms and outdoor kitchens are left as mud.)

We rinsed our hands and arms in a bucket of water and walked back to Jonas’s main family compound, where his other wife, Rebecca, was preparing dinner. She was an older woman of spherical build who, over the course of my three-day visit, appeared in a permanent state of bending over a fire. Until I came back to the village for a Sunday church service, during which she danced like Aretha Franklin, I don’t recall ever seeing her fully upright. Despite what must have been a life of backbreaking toil, Rebecca was cheerful to the point of disbelief. “You are welcome!” she said with a wide smile that revealed several missing teeth.

Then there was Jonas’s younger sister, Charity, perhaps in her thirties, tall and beautiful with the sultry pout of a 1930s blues singer. It was unclear to me if she had a husband, and I could not tell how many of the children in the compound were her own, but her primary job in life appeared to be serving as Jonas’s scullery maid, fetching him water for washing, and serving the meals that Rebecca had cooked.

Several men of the village had gathered around the Burro truck and were looking curiously at the GPS receiver on the dashboard. “Is it a compass?” asked one.

“Well, it can work like a compass,” I said, “but it does much more. There are twenty-four satellites in space, and they talk to this machine. They can tell you exactly where you are, anywhere in the world.”

“Satellites!” said another man knowingly, and they all nodded. I zoomed out the screen to show all of Africa, then zoomed back in to their village (which I had already labeled with a waypoint) and they gasped and pointed. “Africa! Otareso!”

Another man, older and animated, said something in Ewe. Jonas translated: “He says that’s why we call white men trickster dogs.”

It was now five-thirty on the day after the summer solstice. Back home in Maine it would be light until well after nine o’clock tonight, but here it was already getting dark, and quickly. I told Jonas I needed to pitch my tent while I could still see. “Okay, you have a choice,” he said. “You can set up here or at my cottage. Here you may find it noisy at night because I sell alcohol from the store, and the men come around.”

“I’ll take the cottage,” I said. We walked back down the path to his cottage compound, and I spotted a nice location under a mango tree on the perimeter of the courtyard. But Jonas insisted, “No no, you set up here, next to my house, under the roof.” There was indeed a small protective eave, and I had been worried how my twenty-dollar Walmart tent would hold up in a monsoon downpour. So against my first instinct to put some space between us, I relented and pitched under his eave.

Although I was looking forward to a big family meal, Jonas had decided that he and I would eat separately from the rest of the group, which was clearly meant to convey that we were two important men, discussing the affairs of the world, and not to be bothered by mere women and children. He issued an order in Ewe, and Charity sashayed over with a small wooden table. Children arranged our plastic chairs on either side; we sat down and awaited the repast.

Then he told me the story of his two wives. “Rebecca is first wife,” he said. “After many years she could bear me no children, so with her permission I also married Gifty. So I have old wife and I have young wife, who has given me four children.” I later learned from Charlie that Jonas’s church, while nominally Christian, is devoted to the Old Testament. “They are very tolerant of polygamy,” said Charlie, “because you have the biblical story of Abraham and his wives.”

Jonas’s kids range in age from thirteen to three. “My children live here with old wife,” he said (I didn’t need to ask which wife he slept with), which seemed strange since their real mother, “young wife,” lived a five-minute stroll down the path in an identical hut. But it didn’t take long to realize that the main purpose of these children, at least for now, was taking care of Jonas and helping prepare the family meals. Perhaps to demonstrate how it worked, Jonas removed his farm boots and yelled in Ewe. Within seconds, a boy of about six who had been sweeping the dirt compound (on Rebecca’s orders) dropped his broom and rushed to his father’s side. He took away the farm boots, went into the hut, and returned with sandals, carefully placing them, left and right, at his father’s bare feet.

Charity then served dinner, arranging two small covered casserole pans on the table. Before we started, she placed a pan of rainwater and a container of liquid hand soap on the table. (The village has a drilled well with drinkable water about a quarter mile down the road, but carrying water is hard work, so in the rainy season everyone collects rainwater in round clay cisterns fed by elaborate split-bamboo gutter systems around their roofs.) I held my right hand over the pan and she squirted a dollop of soap into my palm. Ghanaians generally eat with their hand, and always the right hand—the left being reserved for what one local guidebook calls “the filthy activities.” So after some one-hand scrubbing, I rinsed in the pan as Charity poured water over my hand from a cup. I felt like a Roman emperor; it was mildly embarrassing. I wondered if she realized that I was just being a polite guest and would never, in my own world, ask a woman to wash my hands—even one of them—before a meal.

Jonas removed the two lids from our dinner service. One pan held the usual brown peanut-based soup (which we would share), laced with spicy peppers and a few bits of bony chicken; the other contained two familiar starchy beige blobs. “Akple!” said Jonas, salivating almost audibly.

“Akple?”

“An Ewe specialty. My favorite food.”

It looked conspicuously like fufu, my least favorite African food, but Jonas explained that unlike fufu it was made with the addition of corn, and it did seem somewhat more palatable than the all-cassava goo I had come to know around Koforidua. “It’s all stomach filler,” said Jan later when I described it to her, which is true—a cheap gluten blast for people who do extreme physical labor, can rarely obtain meat, and have no oven in which to bake their carbs into crusty loaves. Fufu, akple, whatever, is in fact cooked; the cassava, plantains, corn, and other ingredients are boiled before being pulverized into mush. But to my palate it still managed to taste like raw bread dough.

In modern Africa, fufu and its relatives are both a required and an acquired taste. What I mean is, fufu is survival food in these subsistence villages, but even elite Ghanaians with access to pizza love their fufu—although, like Charlie’s family, they buy the just-add-water version from the grocery store. “We don’t pound,” Charlie told me dismissively. “All the neighbors will hear you,” suggesting a stigma attached to the labor-intensive pounding process.

All of this is not to say I dislike African cuisine. Charlie’s wife Afi is one of the finest home cooks I have ever met, in any culture; her versions of the classic Ghanaian dishes—peanut soups, tilapia stew, fried plantains (kiliwili), spicy rice and beans—are bright-tasting, deceptively simple, and stunning on the plate, like the best Mediterranean food. “Okay, now I get it” is about all you say after an all-day feast from her small home kitchen. Like all good African cooks, Afi knows how to extract deep flavor from one-pot meals that do not involve browning, traditionally a prerequisite of Western stews and braises. As with Indian cuisine, which also does not generally start with browning, Africans get flavor from spices and aromatics (dried chilies, onions, garlic) and from long, slow cooking, not from the carbonization that enhances Western meals. This stems from necessity: when you cook over an open wood fire, you are limited in the sauté arts. Also making up for the lack of browning is the earthy flavor of peanuts and the raw taste of bright-red palm oil, the primary cooking fat of Ghana. Palm oil production is a primitive and ancient village industry; all along back roads in southern Ghana, women tend giant boiling vats over charcoal fires, rendering the oil from the fresh crimson palm nuts, a fruit similar to olives that grows in tight clusters the size of beach balls. (What Americans think of as palm oil is what Ghanaians call palm-kernel oil, a clear and more refined product mechanically pressed from the pit, or kernel.)

Jonas said a brief grace in Ewe (concluded by “Amen” in English) and we dug in, tearing off small sticky pieces of akple, which we rolled in our fingers and then dipped in the communal dish of soup. We took turns fishing out pieces of chicken and gnawing off the meat and skin. As we feasted, Jonas explained the economics of farming in Ghana. He recited the annual expenses for his eleven-acre plot:

![]() Fertilizer, seventy-seven cedis

Fertilizer, seventy-seven cedis

![]() Pesticide spray, eighty-eight cedis

Pesticide spray, eighty-eight cedis

![]() Water delivery in drums for pesticide spraying, ten and a half cedis

Water delivery in drums for pesticide spraying, ten and a half cedis

![]() Herbicide (which he calls “weedicide”), ninety cedis

Herbicide (which he calls “weedicide”), ninety cedis

Other expenses include market transportation: the bush taxis charge twenty pesewa for driving his sister to market—plus twenty more pesewa for each bag of cassava that she stuffs into the trunk. (Virtually no farmers in Ghana own cars. Jonas has a Chinese motorcycle that he rides only on back roads around his village because he cannot afford the twenty-cedi registration fee and can’t risk the fifty-cedi fine if he’s caught by police on main roads.)

He pays two cedis per month in dues to his regional agricultural group (the organization that named him Farmer of the Year), called the Akuapem Award Winners Association.

A huge nonfarm expense is education; his three school-age children each cost about one hundred twenty cedis per year to attend private school, one in Accra (where she lives with another sister of Jonas’s) and two in Adawso, the market town ten miles away. Public school would cost slightly less, but the difference is not great because most private schools are church-subsidized, and even public education requires uniforms, books, and fees that parents must provide. The two boys who go to school at the Miracle Child Academy in Adawso ride their bikes to a junction and then take a bush taxi, which is yet another expense.

“The only good thing,” said Jonas, licking his fingers, “is I’m not buying foodstuffs,” which is not entirely true. To supplement his own corn and cassava, he buys a bit of dried fish in the market once a week for adding protein to soups, as well as tomatoes, which he does not have time to grow. (His own chickens, goats, and sheep provide occasional meat, although they are thin because all they get to eat is what they can forage; and he is fattening two wild grasscutters—with grass, of course—in a hutch.) Of course, he can’t grow his laundry soap, matches and other necessities.

In all, his family and farm expenses come to about seven hundred cedis per year, or five hundred dollars. In a good year, he said, he can make eight hundred cedis selling his produce in the market. In theory that leaves him with one hundred cedis in savings, which could be applied to expanding or improving his farm. But in practice, he said, “the rain can fail you at any time.” Last year it was dry, and he ended up losing money.

Jonas would like to improve his already productive farm. With a power tiller (three hundred fifty cedis) he could work more land. A palm-kernel press (one hundred eighty cedis) would let his family extract more oil, and thus profit, from their small palm plantation. But such investments were out of reach. He applied for a loan at the Akwapim Bank, where he saves a little of his profits, and the manager turned him down. In 2007, his agricultural association petitioned the government to provide low-cost loans for farm improvement projects. The 531 members were granted a total of five thousand cedis, or less than ten cedis each. “It wasn’t even worth doing the paperwork,” Jonas said.

While the government claims it does not have money for farm loans, or road improvement, or bringing electricity to these villages, in January 2009 it did find the cash to give outgoing President John Kufuor two fully furnished residences; six new vehicles, fully insured, fueled, and maintained, to be replaced every four years for the rest of his life; forty-five days’ all-expense-paid travel outside Ghana for him and his wife plus a staff of three, every year for the rest of his life; and the equivalent of twelve years’ presidential pay. Kufuor was president for eight years, the term limit, which means his pension will total more than he made on the job (at least officially). He left office voluntarily, which has been rare in post-colonial Africa. But after the payout was announced, critics wondered why anyone but a fool or an utter despot (and Kufuor was neither) would not go quietly given such a lucrative exit package. It could be argued that African leaders like Kufuor are, in effect, paid off to leave peacefully.

Jonas and Rebecca also made money from their store, a rickety wooden stall stocked with sundries and dry goods they bought in the Adawso or Koforidua markets and resold for a tiny profit. More remunerative was the nighttime business, when the store functioned as the village bar, selling only one libation: ten- or twenty-pesewa shots of Jonas’s home-brewed apio, a powerful moonshine distilled from palm wine, with a taste that resembled cheap tequila.

Then there is Burro, from which Jonas earned perhaps ten cedis per month in commission. He said he spent three or four hours a day servicing clients, but much of that time was multitasking—stopping by the huts of clients on his way to and from farming or while running other errands. Being the Burro agent for his village also clearly enhanced Jonas’s already high status. Now, besides being Farmer of the Year and local shopkeeper, he was the go-to guy for rechargeable batteries.

We had finished eating, or so I thought. As I rinsed my hand in the water bowl, signaling I was “satisfied,” as Ghanaians say, Jonas reached over and picked up one of my chicken bones, which I had stripped clean out of respect for the fact that meat is a special treat. He popped the joint into his mouth and crunched noisily. “The marrow is good, many calcium,” he explained. After extracting every digestible molecule from the bone, he spat the masticated shards onto the ground. His flinching dog, so thin you could almost see through him, stopped snapping at flies and rushed over to devour the bone fragments.

Dinner was over.

Jonas explained that Charity would now tend to my evening bath, at which point I confess my mind wandered. “Do you prefer hot or cold water?” she asked—twice, I believe, but possibly more. Appreciating that hot water would expend precious firewood, I finally vouched for cold, which also seemed wise in the event Charity’s responsibilities proved arduous. As things stood, it was a stuffy, humid evening—and after a big meal of steaming hot akple and soup, a cool bath sounded refreshing.

Although the idea of being sponged clean by a nubile Otaresan had its cultural appeal and could have been justified journalistically, it transpired that Charity’s sole task was delivering a bucket of water to my bathing stall. As in most Ghanaian villages, bathing took place in a simple enclosure of woven bamboo and grass walls while standing on a few flat stones. You dip a small bucket into the larger bucket of water and douse yourself. Then you soap up and rinse. As it was already well past dark, I did all this by the glow of a flashlight balanced on one of the walls.

Bathing accomplished and immensely refreshed in clean clothes, I returned to the compound and pulled a plastic chair up under the grass-roofed gazebo that defines the communal space of many African villages. Or rather, I allowed one of Jonas’s sons to fetch me the chair, which I then tried to move surreptitiously into position before he could see me and pounce to help. I have no idea if the Queen of England ever thinks about this, but sometimes I get a feeling that I’d just like to do a few things myself—a challenge when you are an honored obruni guest in an African village.

While Jonas bathed, villagers arrived from their own dinners, the dancing beams of their flashlights drawing closer. A table was pulled up under the gazebo, three kerosene lanterns came alive, and five children gathered to do homework from an arithmetic exercise book. The lantern light was dim and the music from Jonas’s Burro-powered radio (resting on two nails driven into the plaster wall of his house, left of the door) was loud, but life in Africa is naturally distracting and noisy, and I did not sense the children were at all disturbed. It was an average night.

A few men, some of them smoking cigarettes, sauntered up to the storefront and dug into their pockets. Rebecca went behind the counter and carefully poured each man a measured shot of apio, then took their small coins. They drank quickly, in one gulp, then shuffled over to the dirt courtyard and began to dance in the dark among themselves as the radio blasted a Congolese soukous rhythm. Oddly, in a country where homosexuality is a criminal offense, Ghanaian men interact physically without inhibition. Grown men often hold hands in public—indeed, Jonas held my hand as we walked through his village—and dance together, much as women do in the West. They have a completely different code of male bonding that does not rate the insult as the highest expression of affection. This can lead to confusion when traveling with my brother.

Jonas returned from his bucket shower and took his place in the shop stall, portioning out liquor shots to the dancers. “I don’t take alcohol,” he said, “just a soft drink,” and he pointed to a bottle of Malta, the molasses-like carbonated beverage popular in Africa and the Caribbean.

We sat together under the gazebo and watched the dancers. The music changed to reggae, and Jonas sang along. At ten-thirty I signaled I was ready for bed, and we switched on our flashlights and walked down the path to his cottage. The sound of the radio slowly faded; crickets rose in chorus from the black jungle outside the narrow beam of our lights.

I said good night and crawled into my tent. The crickets were loud, but I didn’t mind because it was not the street noise of Koforidua. Alas, rapt appreciation of nature is not the Ghanaian way. In hindsight I might have guessed that Jonas had another Burro-powered radio in his cottage hut, and that the musical soundtrack that accompanies all life in Ghana (and for that matter death, when you consider the country’s raucous funerals) was not over just because it was bedtime. A night satellite image of Africa shows a dark and isolated continent. But if that photo could record sound waves—like the psychedelic blinking “light show speakers” I had in high school—Ghana would glow like a halo.

It was after midnight when Jonas clicked off the reggae music. Two hours later, the rooster started crowing right outside my tent, which I soon realized had been pitched in the middle of the chicken yard. Still, there were no downshifting trucks, no horns, no shouting tro-tro drivers or whining scooters, and I finally dozed off.

At five-thirty I woke to the rumble of distant thunder. A moaning wind beat against my tent, and I heard the sound of footsteps around the dirt yard. I stuck my head outside, under a charcoal gray sky, and saw palm trees arcing in a gale. Chickens scurried for cover and Gifty was quickly taking laundry off the line, which whipped in the wind. “Mister Maxwell!” said Jonas, emerging barefoot from his hut. “I think it’s going to rain—now!”

“I believe you could be right,” I said, leaping from my tent.

“Quick, come inside!” I ducked into his hut just as the monsoon hit. It was the hardest rain I had ever seen in my life, an epochal torrent so loud that we had to shout to be heard.

Jonas’s one-room hut was about ten by fifteen feet in size, with a concrete floor, plastered walls, and a corrugated metal roof supported by tree limbs. On the long side facing the courtyard was a simple plank door with a padlock. The door swung in; on the outside, a handmade paneled half screen door allowed mosquito-free ventilation and a view of the compound. The only other light inside came from a small window, eighteen inches square, on the opposite long side of the hut. This window also had a screen, which hinged inward; on the outside, a wooden shutter could be closed for privacy. Next to the door, a simple worktable, about three feet long, held Gifty’s manual sewing machine and a pile of fabrics. Under the window, a smaller, low table stored an assortment of nested aluminum cookware and plastic buckets. On one end of the hut, farthest from the door, a double-sized foam mattress was laid out on the floor. Above the mattress ran several rope lines, which sagged under clothes. On the floor, a few plastic laundry baskets held more clothes. There were three molded plastic lawn chairs, two adult-sized and one miniature child’s version. The only wall decoration was a calendar from the Apostles Revelation Society. If Jonas were to have cataloged his household goods for an insurance company, that would have been the long and short of it.

We sat in the chairs for half an hour, looking at the rain through the screen door and watching rivers of red mud branch and course like lava through the compound. Gifty had disappeared earlier, perhaps to the kitchen hut. Jonas said that while the rain in general was good, he worried that these gale-force soakers would knock down his corn stalks. “But I mostly worry about hail,” he said. “Hail is very bad.” And then the rain stopped and the sun came out. “Now we must pay our respects to the elders,” said Jonas.

“To thank them for the rain?”

“No no. Because you are an honored guest in our village.”

“Oh, that.”

We walked up the path, now slippery with mud, to the hut of Francis Ahorli, a tall gray-haired man with fine features and the distinguished countenance of an economics professor. From a shady calabash tree in his courtyard hung round gourds the size of basketballs, the type used to make bowls and scoops. “Life here is quiet, but isolated,” Francis said. “Now farming is good; we have the rain,” and he looked up at the sky. “But I have been around long enough to remember the times of no food. The politicians care about the people in the cities; they can organize and make trouble. Out here, we do not get heard. We need good leaders in our country who will keep us from hunger.”

Francis joined us for the short stroll to the home of the village’s most important elder, Kofi Adri. We sat on a wooden bench on his porch and were joined by Joshua Asinyo, the village linguist. (In a formal meeting, it is considered disrespectful to speak directly to a chief or elder; instead, you speak to the linguist, who then speaks to the chief. As the chief is sitting right there and can obviously hear you, it feels a bit forced, but that’s the tradition.) Joshua was a middle-aged man severely afflicted with late-stage yaws, the disfiguring African disease related to syphilis but not transmitted sexually (it generally attacks children). Of all the developing-world ailments, yaws is especially tragic because in its early, highly contagious stage it can be cured with a single dose of penicillin. Without that simple treatment, however, it advances to an incurable scourge. The result could be seen on Joshua, whose entire body, including his face, had been transformed into an unrecognizable mass of giant wartlike welts. It was frankly hideous—if he were a monster in a horror movie you would jump out of your seat—but the bigger surprise was how utterly cheerful and content he was, despite his unsightly plague. Like most Ghanaians he was deeply religious (also a member of Jonas’s church), and he had obviously found some transcendent inner peace that was enviable.

Jonas spoke to Joshua in Ewe, and Joshua then repeated to the elder. I had brought along the traditional offering of a bottle of schnapps, and it was ceremoniously presented to him. He thanked me for my interest in his village and, through Joshua, ordered a gong-gong meeting for the next morning to discuss the use of Burro batteries. After receiving his permission to leave, we shook hands and walked back to Jonas’s main compound for breakfast. Jonas’s children served us steaming cups of tea sweetened with Milo (the Nestlé malted chocolate drink) followed by delicious omelet sandwiches in sweet tea bread. At the window of Jonas’s shop stall, several men were getting fortified for their morning farming with a shot of apio. I thought of rural France, where I had often seen men knocking back “eye openers” of pastis before heading to the vineyards.

Soon Joshua returned to announce tomorrow’s gong-gong. He was also the village gong-gong man, a job he had redefined with modern technology. Instead of the typical cowbell, Joshua’s “gong-gong” was a battery-powered megaphone—the sort that might be used by the fire marshal in a small-town Fourth of July parade. While Jonas sharpened my machete on a flat rock next to his shop, Joshua turned on his megaphone and marched up and down the dirt track, announcing tomorrow’s meeting through the tinny, crackling loudspeaker.

Moments later Jonas’s children, who had evidently bathed after preparing our breakfast, emerged from their huts in crisply pressed school uniforms. They grabbed their knapsacks and headed off, on foot and bicycle, to secondary schools in the outlying market towns and larger villages. Otareso has its own informal elementary school (there is no building), but its status is in limbo. Jonas introduced me to Georgina, the young woman who is the teacher for the village. “When does school start?” I asked her.

“We don’t start,” she said. “I expelled the students last week because the parents don’t pay me.” She said this without anger or malice, simply as a fact. “And when we have a PTA meeting, they don’t come. It’s very painful, but I have to feed and clothe myself. Until the parents come up with something reasonable …” She shrugged.

It was time for work. Jonas and I slipped on our boots, grabbed our machetes, and walked to the fields. The morning job was planting cassava cuttings—inch-thick stalks that take root in the rainy season. To use his land most efficiently, Jonas interplanted cassava between the corn stalks, which were perhaps a month away from harvest. By the time the slow-growing cassava was ready to harvest early next year, the corn would be long gone. So by timing his interplanting, Jonas was able to grow two crops on the same plot at once.

Along the path, Jonas marshaled two women to join us, speaking in Ewe. We arrived at a field that had grown cassava last year and was now fallow. A few days earlier, Jonas had gathered two large bundles of five-foot-long stalks and tied them with strips of palm frond. “The women will carry these to our field,” he said.

“What do we carry?” I asked.

“Our machetes.”

I shook my head. “What if we made four bundles and we helped? Then the women would not have to carry so much.”

“In our African culture,” he replied in a tone that brooked no argument, “women carry.” Chivalrous African men like Jonas, however, do make it a point to arrange the loads properly on the ladies’ heads. We hefted the giant bundles aloft and followed the women as they walked—erect, straight, and perfectly balanced—to the cornfield ten minutes away.

Jonas had a distracting habit of gesticulating wildly with his machete as he talked, and I was careful to keep some space between us on the trail. Finally we reached the corn, about knee-high, and he ordered the women to drop the bundles. They left, and our work began. Jonas showed me how to bore a shallow hole in the soil with the tip of the machete, push the cassava stalk in at a slight angle, and deftly whack off the stalk about a foot from the ground. Then he moved to the next space between the corn, dug another hole, pushed in the stalk, and whacked it off as well. It took practice to make a neat slice of the stalk in one cut; even though my machete was razor-sharp thanks to Jonas (I jokingly tried shaving with it, and it worked), I was too timid in my attack. The result was a mangled stalk. I also had to practice not making the hole too deep, which Jonas said would cause the cassava root (which is the edible part) to grow too far under the surface. On my own, I recognized the additional importance of avoiding my feet on the downstroke; my rubber boots were not steel-toed. But after about an hour I was almost keeping up with Jonas’s steady rhythm of dig, poke, whack … dig, poke, whack.

I was also foaming with sweat like a draft horse. My clothes, the latest in high-tech “wicking” fabrics from REI, were as soaked as if I had stood out in the morning monsoon, the memory of which had now long faded. The sun attacked without mercy; I felt we were on some other planet, several million miles closer to the fiery ball in the sky. As I bent over my machete, perspiration dripped like steam from my brow, stinging my eyes and fogging my glasses. I had a small digital camera in my shirt pocket, which was now soaked through; I tried to find a dry pocket, but there was none anywhere on my body. There was no shade within sight. It was still early morning.

“Are you hot?” asked Jonas.

“Just a bit,” I allowed, between panting breaths. “How about you?”

“No.” Jonas was wearing corduroy pants and a pilled polyester golf shirt under a heavy wool gabardine top, buttoned at the cuffs. His brow was completely dry. “The rain has cooled the day nicely.”

Although I cannot back this up scientifically, I am certain that after three hours planting cassava, my machete had gained approximately ninety pounds, and I had lost perhaps half that in water weight. I did not protest when Jonas decided it was time for lunch. We had planted perhaps half an acre; only about ten more to go.

Lunch back at the compound (cooked by Rebecca and served as always by Charity) was banku and fish soup, deliciously spicy.

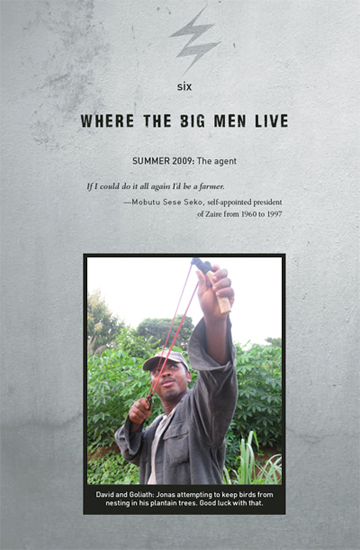

For our afternoon work, Jonas apparently took mercy on me and decided we would work in the shade of the nearby plantain grove. As we walked down the path, he unsheathed a slingshot from his back pocket and fired rocks into a mango tree, causing hundreds of weavers to scatter in a cloud so large it momentarily blotted out the sun. “Those birds, they spoil the plantains,” he said spitefully. I wasn’t sure if his slingshot attacks would do much to prevent them from nesting in his plantain trees, but they seemed to make him feel better. A few yards farther down the path, a goat was busy uprooting cassava stalks Jonas had planted last week. He loaded his slingshot and fired a rock into the goat’s hindquarters, which sent it braying across the field. You don’t mess with the man’s crops.

The plantain grove was spread out along the main road to the village. Here too, Jonas was attempting to use his land as efficiently as possible. “These are orange trees I have planted between the plantains,” he explained, pointing out the two-foot-high saplings with their shiny leaves. “We need to clear the brush around them”—a foot-high shag carpet of grass and woody clumps that grow like mildew in the relentless heat and sun of Ghana. He demonstrated how to use the machete like a scythe, swinging wide arcs parallel to the ground—ideally without lopping off the orange seedlings.

We got to work and I was soon dripping again, despite being in the shade. This time, however, our labors were highly public, as villagers passed in a steady flow of foot traffic along the road, carrying water jugs on their heads. As far as I can tell, few entertainments are as capable of sending Ghanaians into knee-slapping hysterics as the pantomime of a white man performing manual labor, and I endured several hours of exuberant laughter and catcalls. Sometimes people would simply stop and watch for several minutes, as though taking in a sporting event. This is understandable when you consider that the African’s relationship with the white man has long been one of servant and master, and I’m not even talking about slavery. During the colonial era, it was considered perfectly normal for Africans to carry the British around on throne-like hammocks. In his 1883 book To the Gold Coast for Gold, the British explorer Sir Richard Francis Burton decried the incompetence of his Ghanaian porters, whom he felt were overpaid:

As bearers they are the worst I know, and the Gold Coast hammock is intended only for beach-travelling. The men are never sized, and they scorn to keep step, whilst the cross-pieces at either end of the pole rest upon the head and are ever slipping off it. Hence the jolting, stumbling movement and sensation of feeling every play of the porters’ muscles, which make the march one long displeasure. Yet the alternative, walking, means fever for a newcomer.

An arduous journey, indeed. When you consider that Burton was in fact a seasoned adventurer and keen student of indigenous culture—he spoke many African and Asian languages and once visited Mecca in disguise as an Arab—you can imagine how a less dogged Western traveler would expect to be coddled by the Africans. No wonder the locals marvel when a white man swings a blade.

By the end of the day, I had earned my farm credentials. “You know,” said Jonas at one point in the afternoon, “I believe Americans are stronger than Europeans.”

“Yeah, those Europeans,” I said, looking up from my labors. “What a bunch of pussies!”

“Pussies! Ha!” said Jonas.

“To be honest,” I said, “my grandparents were European.”

“Really?” he said, as if I had suggested they were Uighur herdsmen.

“Yes, from Eastern Europe, like many immigrants to America. And it’s pretty unlikely the gene pool has evolved much over two generations to make me noticeably stronger. Besides, there are many strong Europeans. Look at Andre the Giant. He was French.”

“I don’t mean giants,” he said, “just regular people.”

The conversation segued into a discussion of the American melting pot. Jonas pointed out that Otareso is also a melting pot, being a haven for migrants from Benin and Togo. “That explains why we are so friendly,” he said. “We like foreigners because we are foreigners.”

Back at the compound, we peeled off our farm clothes and bathed before dinner. “You should not leave your boots in the bed of your truck like that,” Jonas told me as I combed my hair by the side-view mirror. “Someone could come by and take them.”

It struck me as an odd concern in a village of two hundred people who know one another like family. “Is there a bad man in this village?” I asked.

“Oh no, there is no bad man,” said Jonas. “But you never know.” (A few months later, someone broke into Jonas and Rebecca’s store in the middle of the night, on a looting rampage.)

Dinner was more starchy mounds, more brown soup. Again the women served us. A soccer game played on the radio, announced in Twi. I tried to strike up a conversation with a young village boy who had been eyeing me with curiosity. “He speaks no English,” said an older boy. “He doesn’t go to school.” The boy kept staring at me. I asked the older boy if he liked football, and he said he listened to the Phobia games; Phobia is the nickname for the Accra premier-league team. I asked if he liked to play football himself. “I would,” he said, “but the village has no ball.”

Five degrees above the equator, the sun does not linger at the horizon, and darkness descended quickly on Otareso. My energy faded with the light; I was exhausted. As Jonas and I headed down the path, twirling our flashlights, I remarked on how the whole village seemed to just disappear into the sudden blackness of night. “We will get light soon,” he said. “It is coming to our village.”

Actually it isn’t, no matter what the politicians promise. Electricity will not come soon to these villages. But wherever I went in Ghana, that’s what people said: It is coming soon. We are next. Very soon.

Instead of light, they get stars. There was no moon and the night was clear, and the Milky Way split the sky in two. The stars faded along the southern horizon, where the glow from electrified Accra washed out the black sky. And along the western horizon, high up on the Akwapim Ridge, the lights were coming on in the houses where the Big Men live.