A week later I arranged a village stay in Sokwenya with Hayford Atteh Tetteh, one of Burro’s first agents and, at age sixty-four, the oldest. Hayford, a farmer, was a member of the Shai tribe, a subset of the Adangbe nationality, which is itself part of the larger Ga-Adangbe ethnic group. Although lumped together as descendants of ancient Nubian fishing people who settled in and around Accra, the Ga and the Adangbe now speak distinct languages—Ga and Dangbe—that are mutually unintelligible. However, as in Jonas’s village, Sokwenya was vibrantly multicultural; despite the presence of many Shai, the chief was Akwapim.

Sokwenya lies off a formerly paved, primary route that was now a virtually impassable dirt road several kilometers west of the market town of Adawso. The morning of my visit I met Hayford in Adawso, where he had been delivering batteries on his bicycle from a cheap zippered red shoulder bag emblazoned with the word FLORIDA; we loaded the bike into the back of the truck, shifted into four-wheel drive, and headed out of town.

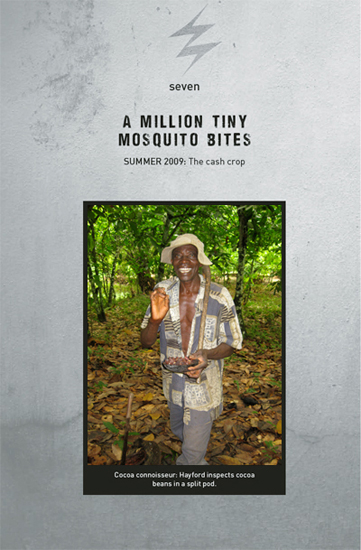

A wiry, gray-haired man with a long face and a seemingly permanent smile, Hayford was possibly the most pleasant individual I had ever met—and that’s saying a lot in Ghana, where people seem to be genetically good-natured. He had a mannerism that involved laughing and extending a handshake whenever conversation reached a point of agreement or empathy—as if to say, “I’m with you, let’s shake to that!” For example, told that I once lived in New York, Hayford replied, “I have a cousin in New York!” followed by a laugh and a conspiratorial handshake. To spend an hour with Hayford is to shake hands elaborately more than several dozen times, to the point where I started to wonder if it made more sense for us to simply hold hands and be done with it.

Unlike his cousin, Hayford had never been to New York. He had never been to neighboring Togo, or even to most places in Ghana. But he was proud of his ten years’ formal education (at the Old Mangoase Presbyterian School from 1956 to 1966) and he spoke English better than most younger Ghanaians—well enough to converse freely. As we drove, he expressed pointed curiosity about race relations in America. As an elected subchief of his village—his title was amankrado or “opinion maker”—Hayford was an important elder. He was also a leader in his Presbyterian church.

“Do whites and blacks mix?” he asked.

“That’s a hard question to answer,” I said. “It’s a big country. In some places they do, in others not so much.”

“Do they marry each other?”

“Sometimes. My brother is married to a black woman.”

“Whit’s wife is black?”

“Another brother. And many if not most African Americans have some white ancestors. They’re not as dark as you.”

Hayford laughed at that, and we shook hands. We drove on, slowly. The recent rains had turned an already bad road into a theme park ride of mudslides and yawning sluices. We passed several bush taxis and tro-tros fender-deep in muck, their passengers engaged in strenuous efforts to push and pull the vehicles free as the tires spun out ribbons of red clay. Occasionally we stopped to pick up a pedestrian or a waylaid taxi passenger—Hayford knew practically everyone along the road—and load their plantains and sacks of cassava into the truck. When the cab filled, more people jumped into the bed along with the produce; soon we were bouncing along under a mountainous load of human and vegetable cargo, plus several bicycles.

The passengers in the backseat did not seem to speak much English, so Hayford and I continued our own discussion. “Where are your Negroes from?” he asked, meaning where in Africa.

“All over. Some know, but most don’t,” I said.

“Really?” That seemed inconceivable to him.

“It was a long time ago, and slaves were not exactly encouraged to remember their past. At this point they just consider themselves African American. You know, I can’t think of a single black American I know who identifies with a particular African country or ethnic group.”

“Obama does; he is from Kenya.”

“Well, he’s different,” I said. “He’s not from slaves, like his wife. I doubt if she knows where her ancestors are from. Whoa!”

I stepped on the brakes. Just ahead, around a bend, the muddy track ended at the shore of what looked like a small lake. The road simply disappeared into the murky, brick red tarn. In the distance I could vaguely make out the track as it reappeared from the far shore. I looked at Hayford. “Now what do we do?”

“It’s okay. Let’s go.”

“Through that water?” I glanced in the rearview mirror at the bed of the truck, overflowing with produce and people. I wondered if the Tata could float, and if not how I would explain a sunken truck to Whit. “You’re sure?” There were waves breaking across the surface of the water.

“Let’s go.”

I shifted from four-wheel high into four-wheel low and inched forward. In we went, deeper and deeper. The water swirled around the doors. I sensed a current pulling us sideways, then realized that what I thought was a lake appeared now to be a fast-moving river. At this point the mass of humanity in the bed of the truck struck me as an advantage; I hoped the weight would act like a sea anchor to keep us tracking through the gulf.

We made it, finally, and crossed a couple more streams before Hayford indicated I should pull over on the right, in a jungle clearing. “We shall walk from here,” he said. I parked, and our passengers began unloading their goods. Across the clearing, several men were laboring over steaming cauldrons that indicated a backwoods distillery. “This is where we make the alcoholic,” announced Hayford.

The nerve center of the operation was a sealed fifty-five-gallon steel drum perched on rocks over a searing wood fire. Inside the drum, palm wine boiled and evaporated into a length of copper tubing fitted into the lid. The tube then coiled around and circulated through two more drums filled with cold rainwater, which condensed the vapor into alcohol. At the bottom of the last drum, the tubing emerged over a filter funnel placed in a large plastic jug, which rested in a hole in the ground. The clear condensed alcohol dripped slowly from the tube, into the funnel, and down to the jug. The filter seemed to be a good idea because the surface of the liquid, which was backed up in the funnel, was covered with a silvery skin that looked like mercury. I wondered if metallic scum was a normal by-product of the distillation process, or if it had something to do with the use of old oil drums.

“Very strong alcohol,” said Hayford.

“What’s that stuff in the filter?” I asked.

“We take it away,” he replied dismissively, waving his hand in the direction of the jungle, like a public relations officer for a chemical plant. Fortunately, a tasting was not in the morning schedule. Like Jonas, Hayford was happy to make and sell moonshine but never touched the stuff himself.

“Let’s go,” he said, and we gathered our stuff and headed down a jungle path so narrow that I could barely put one foot in front of the other. Soon we came to the bank of the Osoponu River, a brown, fast-moving stream. There was no bridge, just a few rough-cut timbers balanced precariously on rocks and logs across the deeper parts of the ford. “Follow me,” said Hayford. “Step where I step,” and we proceeded slowly over the rickety boards. Hayford carried his bicycle, and I carefully held my sleeping gear above my head. Halfway across, the boards ended and we stepped into the stream, which began swirling around the cuffs of my calf-high rubber farm boots; I sincerely wanted to avoid having my boots fill with water, but for Hayford the problem was immaterial as his own farm boots had gaping holes in the toes and heels. We made it without incident, and on the far bank the overgrown trail continued half a mile to the village itself.

My earlier stay in Otareso with Jonas had left me feeling well prepared for the rigors of Ghanaian bush life, but I now realized that Jonas’s village was Shangri-La compared to Hayford’s grim outpost. Where Otareso was situated on a high, grassy plain with big views of the sky and cooling breezes, Sokwenya was claustrophobic, damp, and dark—a haphazard collection of compounds strung along the densely wooded canyon of the riverbed. The town had no well; water was carried in jugs from the muddy river or collected in rain barrels. The air, or what passed for it, was stiflingly humid, like breathing through a wet sponge. It was, ecologically speaking, a perfect malaria microclimate, and clouds of tiny mosquitoes vibrated like auras around our heads.

And yet this seemingly cruel human environment was perfect for growing cocoa, which thrives in warm, humid zones, generally within fifteen degrees of the equator. Cocoa was Hayford’s primary cash crop, and indeed the most important source of income for many of Burro’s customers; it made sense to see where their money came from. He also planted half an acre of maize and cassava, and he grew some plantains, okra, tomatoes, and peppers. But by his own admission he was getting too old to wield his machete across large fields of annual crops. Mostly he tended his valuable cocoa trees.

“You will stay here tonight,” he said as we rounded a bend in the trail and emerged in a clearing where a long tin-roofed hut, its beige stucco walls crumbling, slumped behind a cracked concrete patio on which cocoa beans dried in the sun. We entered the hut, which had two rooms. Hayford pointed to a spot on the floor where I could sleep. I set up my mosquito netting and unrolled my bedding. “I was born in this room,” he said, with his twin brother, which explains his name. In Ghana, the older of male twins takes the second name Atteh, while the younger is known as Larweh.

Now the compound belonged to Hayford’s sister Agnes, who was queen mother of the village. Contrary to how it sounds, a queen mother is generally not the mother of the chief. Her role is more that of wise counsel and keeper of all genealogical knowledge. As such, she plays a key role in choosing the chief. She is also treated with great deference—a custom not lost on Agnes, a physically substantial woman who apparently did not share Hayford’s easygoing nature. When I reached out to shake her hand, she pointed at my feet. “Give me those boots!” she said. “Mine are worn. I need new ones.”

“Umm, no thank you,” I said, not really knowing what else to say when the queen mother asks for your only shoes.

The silence was awkward, and I was glad when Hayford yet again said, “Let’s go.” We walked another hundred yards down a trail to his own compound, where his wife, Rose (small and quiet, gray hair under a green head scarf) was tending the cook fire and his grown daughter, Dora (tall, with straightened hair pulled into a bun) was washing clothes in a bucket. They smiled and waved. Hayford went inside to change into his farm clothes, apparently a different ensemble of tattered polyester slacks and golf shirt than those he was wearing. My phone rang and I engaged in a brief transatlantic chat with Sarah.

“I like your phone,” said Dora when I hung up.

“Oh, thank you,” I replied, finding the compliment strange, as even by African standards my cell phone was a no-frills el cheapo. Except for an obviously fake iPhone I once saw (spelled IPHOUE and bearing no resemblance to the real thing apart from its counterfeit Apple icon), my phone was about as crappy as they get in the developing world.

“Will you buy me one?” she said. Now I understood. In Ghana, praise is often a hint for a gift. Whit later told me he’d first noticed this years ago when learning that a single word in one of the neighboring lingua francas means both “to like” and “to want.” Clearly the gimme culture was alive and well in Sokwenya.

Whit and I made it a policy never to give in to begging in Ghana, except for cases of the obviously homeless and handicapped—conditions sadly on the increase, according to our African colleagues, as modernity erodes traditional family values and the weakest members of society lose their support system. But often healthy and secure Africans (in a relative sense, granted) will ask for money, or gifts, simply because they know some Westerners will “pity” them and take the easy path of tossing a few bills. Thus encouraged, they naturally beg all the more, which leads to cynicism and the opposite of the enterprising spirit that Whit was trying to develop. “If you give me forty cedis,” I said, “I will buy you a phone just like this one and have it brought to you.” She frowned and went back to her laundry.

Hayford’s dogs were even skinnier than Jonas’s, so slight and thin that at first I mistook them for purebred Chihuahuas. During my medical checkup before coming to Ghana I declined to buy the eight-hundred-dollar rabies vaccine (why is it forty dollars for dogs?), vowing to my doctor that I would steer clear of vicious village pets. But these starving and no doubt worm-infested mongrels appeared too fragile to bite anything; I worried that a strong wind would turn them to dust, like Egyptian dog mummies.

Hayford emerged with his machetes—three styles, each for a different task. He examined my own blade carefully. Even though Jonas had recently honed it to a razor’s edge, Hayford pronounced it hopelessly dull. He stooped over his sharpening stone and worked the blade back and forth for a good twenty minutes. “That’s better,” he said. “Let’s go.” He untied a goat that had been leashed to a tree and pulled and dragged the loudly complaining animal down a steep trail as I followed closely behind.

In a few minutes we arrived at a field of elephant grass under the power lines, which traversed his property but of course did not provide any electricity to Hayford’s village and probably never would. He tied the goat to a bush and left him to graze while we continued on. Soon we came to his cocoa plot, spread out along the bank of the narrow river.

Cocoa trees are small and gnarly, almost like overgrown bushes, with long, oval leaves. The cocoa beans grow inside strange football-shaped pods that emerge from flowers on the trunk. The pods grow to around ten inches long and start out green but turn lemon yellow or bright red (depending on the variety) as they ripen. In the right environment, a cocoa tree can produce beans for seventy-five years, but they are finicky. Besides heat, they need around eighty inches of annual rainfall and filtered shade, which is why they do well along sheltered riverbanks and under larger trees with broad shade-producing leaves, like plantains and bananas.

Hayford whacked a pod off a tree with his machete, then deftly wielded the blade to split it open. He held out the dissected pod in his long, creased fingers. Inside, rows of thumb-sized purple cocoa beans—the tree’s seeds—were embedded in a fibrous white pulp. To yield the cocoa, Hayford explained, he would ferment the bitter-tasting beans between wet banana leaves for six days, which removes the pulp and develops flavor. Then he would dry them in the sun for five days before selling them to processors, who roast the beans, then remove and discard the outer shell. The remaining portion, called the nib, goes through further elaborate processes (including the addition of milk solids and sugar) to become chocolate. To someone like myself who could eat chocolate at every meal, Hayford’s cocoa plot was the Garden of Eden. “Let’s go,” I said.

“First we shall pray,” said Hayford, bowing his head. “Oh Lord, we have come here to work, so you shall abide us so that we don’t have any troubles.”

As it happened, Hayford’s cocoa trees were having some troubles of their own—an outbreak of powdery mildew after the rains. “I need to buy copper spray,” he said.

“Fungicide,” I said. “We use the same stuff on fruit trees in Maine. But, Hayford, look at this.” I pointed to the base of the trees, ringed with thick mats of brush and weeds. The river had obviously overflowed its banks recently, and all the floating debris had been trapped around the trunks of the cocoa trees. “Look, I don’t know beans about cocoa, but that can’t be good for the trees,” I said. “It’s probably choking them, and I think it’s encouraging the mildew.”

“Yes yes, I see,” said Hayford. “We should remove it.”

So we did, pulling away the brush with the curved points of our machetes, then chopping down the surrounding vegetation. Next Hayford walked through the grove pulling up tiny cocoa shoots that had sprouted under mature trees. “We will plant these in better places,” he said, explaining that the new shoots need more sun. We carefully cleaned and trimmed the roots, stripped off the leaves to encourage new stem growth, then poked holes in the ground with a sharpened stick and replanted the shoots.

“So next week you’ll have new trees here?” I said.

“Hah!”

“Seriously, how long before these yield beans?”

“About two, three years,” he said.

“That’s all?”

“They grow very fast,” he confirmed. “Some hybrids, even faster.”

We moved downstream, clearing more brush with our machetes. It was pleasant work in the shade of the trees, even with the mosquitoes. “Are you tired yet?” Hayford asked.

“No,” I said. “I’m fine.” Which I probably would have said even had I been close to sunstroke, but this time I actually meant it.

A few minutes later he asked again. “Do you need to rest?”

“I’m fine.”

The third time he asked, it dawned on me that maybe Hayford himself was tired and was trying to save face, so I agreed to head back.

At Hayford’s compound, we drank tea and listened to a soccer game on the radio; Accra’s Phobia was playing the All-Stars of Wa, a provincial capital in the north. Hayford had become his own best Burro customer: he told me that he used to ration his radio use carefully, but since signing on as an agent he played it all the time—mostly gospel music.

After an hour or so, Dora’s sons—four of them, all under ten or eleven—returned from school. Hayford has seven offspring and an indeterminate number of grandchildren because, he says, “some of my kids live in the forest, so I don’t know how many children they have.” While Hayford resharpened my machete, I sat down on a bench with Maxwell, Adjei, Amos, and Samuel as they worked on their math books. Adjei, the youngest, had bare pink spots the size of nickels all over his head—ringworm. All the boys had scabby insect bites all over their bodies.

“Do you have mosquito nets for your beds?” I asked.

“No,” said Maxwell, the oldest. “We get sick.”

Dora snapped an order at the children, and they scurried to round up fallen coconuts from the surrounding trees. They took turns hacking away at the shells with a machete, preparing them for tomorrow’s market day. It looked incredibly dangerous; I figured no amount of practice could give ten-year-olds the physical coordination to use a machete safely. After a few minutes I turned away, unable to watch. An older boy in a school uniform, whose name I didn’t get, came home, pushing a bike with a flat tire. He went into the hut, came out changed, and proceeded to repair the flat tire on his bike. His mobile phone went off; the ring tone was the Shaker hymn “Simple Gifts.” He set down the tire and spoke on the phone in Twi for several minutes.

It was dinnertime. Hayford and I ate first, sharing fufu and a bowl of bright red palm nut soup with a few chicken livers and gizzards. Hayford made sure to offer me the livers first. After we ate, he carved a couple of toothpicks from twigs and handed me one. He went to bed at eight, and so did I.

A goat in my room woke me early the next morning. I shooed him out, then followed through the door to brush my teeth. I was greeted by a boy of about nine named Sammy, who handed me a plastic cup of rainwater. The index finger of his left hand, or the half that was left of it, was wrapped thickly in gauze. “What happened?” I asked. He spoke no English. I pointed to the wound and he made a chopping motion with his other hand.

Breakfast with Hayford was a shared bowl of sweetened porridge and tea bread. “When did the boy lose his finger?” I asked.

“Last Tuesday. He was in a cocoa tree with the cutlass, holding a branch with his left hand. He’s a lefty so he was trying to cut with his right, which is not good.”

I wanted to add that perhaps it wasn’t good for ten-year-olds to be pruning trees with machetes, but I held off. A billboard seen along roads all over Ghana said AGRICULTURE WITHOUT CHILD LABOUR IS POSSIBLE! Maybe so, but for most Ghanaians it certainly wasn’t practical. A September 2010 report by Tulane University’s Payson Center for International Development said hundreds of thousands of children work on cocoa farms in Ghana and next-door Ivory Coast; many are trafficked and forced into labor.

“Did he get medical care?” I asked.

“There is a clinic in Adawso.” Remembering the road we had taken, I imagined a long, agonizing trip.

I had to get back on the road to Koforidua, but first Hayford wanted me to meet one of his brothers who was a preacher—not his twin, another brother, named Kwesi, which means “born on a Sunday.” We walked up a hill to Kwesi’s house and sat in chairs under a raffia awning. It looked like rain; Hayford was wearing a long trench coat and complaining about the cold, even though it was in the eighties.

“Are you Christian?” Reverend Kwesi asked me.

“I grew up Catholic.”

“Do you believe in the Holy Spirit?”

“It’s an important part of Catholicism,” I replied, trying to stick to the facts as I remembered them from Sister Madonna’s second-grade classroom.

That seemed to satisfy him, and he abruptly changed the subject. “Do you grow cocoa in America?”

“Oh no,” I said, somewhat relieved that we had moved on from the Holy Spirit to agriculture, a subject on which I felt firmer terra. “Too cold. Not even in the far south. Not even Hawaii.”

“Does it snow where you live?”

“Very much. And the lakes freeze so thick you can walk on them.”

“No!”

“I swear it. Like Jesus on the water.”

“Hah! Like Jesus!”

“You can even drive cars on the ice when it gets really cold.” This was a bridge too far, beyond Ghanaian comprehension, and I gathered they thought I was joking.

“Of course, every year, someone’s car goes through the ice,” I added. Kwesi thought that was hilarious, which it sort of is, if not to the driver.

Hayford’s brother had a Chinese bike that needed fixing—not a Walmart Chinese bike with sparkle paint and a pseudo-English name, but a real made-for-Shanghai bike, plain black with Chinese writing. Could I take it into the shop in town? I agreed, and accepted a ten-cedi note for the repairs. The bike was a mess—flat tires, bent rims, missing brake cables, no doubt much more. In America and probably even China it would go to the dump, but not here. I was looking forward to meeting Dave Branigan, the American who ran the bike shop around the corner from us—the former Peace Corps worker who had been beaten in his own home by Nigerian gangsters.

Back in Kof-town I coaxed the bike across the street—the rims were so bent they thumped like a djembe on the pavement—and down the alley to the shop for Ability Bikes, the nonprofit venture that Dave ran. Three Africans—one woman, two men, all of them polio victims on aluminum crutches, were hard at work on various disabled bike frames. At the front of the shop, working on another bike, was a blond white guy in his mid-thirties with a nasty fresh scar under one eye.

“Excuse me,” I said. “I need to get this thing ready for the Tour de France.”

He looked up and extended a hand. “You must be Whit’s brother.”

“I’m Max. You must be Dave.”

“Pleasure. Where’s Whit?”

“He’s in China on mission impossible—trying to get factories to make twenty-dollar flashlights for fifty cents. Speaking of China, I’ve got one of their finest for you.”

Dave looked at the bike and exhaled deeply. “Bad timing. I’m on my way to Tema. Container of bikes just came in. I’m swamped. But let’s take a look.”

The way Dave’s business worked was he got charity bikes sent over from the States—wrecks that somehow escaped the dump—which he reconditioned on the cheap for local consumers. In the process he trained disabled Africans to repair bikes, building skills for people who might otherwise end up as beggars. His venture was affiliated with a Boston organization called Bikes Not Bombs that promotes bike empowerment in poor countries around the world, as well as in American cities.

“Thanks, Dave,” I said. “By the way, our agent gave me ten cedis to fix this thing.”

“That’ll be tough,” he said, stooping to examine the twisted carcass. “Let’s see … definitely needs tubes and tires. I’ve got some used tires I can throw on, and if I buy the cheap Chinese tubes he’ll save a couple cedis. We can probably straighten the rims rather than replace them; they’ll be good enough to ride, anyway. Brake cables, I’ve got some used over there. Looks like the whole front brake assembly needs replacing.” He started writing down figures.

I wanted to ask Dave about getting cracked over the head with a mahogany plank in his own bed (“What’s that like?”), but it didn’t seem like the right time. “We’ll need some grease, maybe an hour of labor …,” he went on. “I’m guessing this all comes to about nineteen cedis.”

“Let’s do it,” I said.

Dave looked up at his workers. “Anybody have time to do this job over the weekend?”

“I will do it,” said a tall man on crutches with toothpick legs and a bodybuilder’s chest popping out of a bright red Arsenal soccer jersey.

I thanked Dave, made a mental note to ask him later about Nigerian thugs, and walked back across the street to home and a hot shower. On the way I ran into Kevin, who had just come back from his route.

“Hayford says you worked very hard on his farm,” Kevin said.

“Well, I wanted to work even more, but I think he was tired.”

“Oh, he told me about that,” said Kevin. “He said he was afraid you were going to cut your leg off with the cutlass.”

Back in our flat, I stood under the shower and watched the mud of Sokwenya swirl around the drain, and I felt deliriously comfortable and guilty. A white person in Africa can feel guilty about almost anything. I felt guilty that I could be enjoying a hot shower when people like Jonas and Hayford had to bathe in a bucket; guilty that I used conditioner in my hair; guilty that after dark I could turn on lights and cook over a shitty but serviceable gas stove, or (if I wanted) drive to get a shitty but edible steak in a hotel restaurant; guilty that I didn’t chew my chicken bones; guilty that I accepted ten cedis from Hayford for the bike repair when I could easily afford to foot the whole bill myself; guilty that I did not give my farm boots to the queen mother and go barefoot like so many Africans I saw every day; guilty that we were trying to make money off people who were so poor they needed to let their children work with machetes; guilty that I could go home.

Yes, it’s easy to feel guilty in Africa, but it was also easy to forget that Whit was giving people jobs and teaching them skills; that I was paying for half the bike repair; that I gave Hayford and Jonas nice gifts (heavy-duty Coleman flashlights unavailable in Ghana) and that I helped them on their farms without cutting off any body parts; that I was a long ways from home in a dangerous place. All these conflicting feelings rose and fell like a blush, and soon they disappeared like the red dirt down the shower drain, and all that remained was a million tiny mosquito bites.