I could handle the concept that batteries need good nutrition and regular exercise. It was the last sentence that got me: Each battery seems to develop a unique personality of its own. I was out on the veranda reading Isidor Buchmann’s battery bible, hoping to learn more about the product at the center of the Burro business. Buchmann is a Swiss-born Canadian inventor who, according to Whit, made a small fortune in the early days of the cell-phone business by helping phone manufacturers get a handle on runaway battery returns. He helped them figure out why seemingly good batteries went bad—that is, failed to take a charge—and how to analyze and recondition them. Being a techie nerd, Whit loved this kind of stuff; he went so far as to telephone Buchmann, twice, exchange several emails and, on one trip home to Seattle, have lunch with him over the Canadian border. I, on the other hand, expected his book to be eye-glazingly technical and dry as a camel bone. In fact it was surprisingly readable. To be honest, I soon found myself transported far from the dusty streets of Kof-town to a science-fiction netherworld where batteries were like HAL, the malicious computer with a mind of its own in 2001: A Space Odyssey.

If Buchmann can be taken literally (and the man is nothing if not a precise writer), batteries are not merely good or bad, strong or weak. He says each battery develops its own personality. Think about it: that’s a lot of personalities. Taking Buchmann’s analogy to its nightmarish conclusion, batteries have the potential to be temperamental, stubborn, melancholic, curious. And that’s just a four-pack. It gets worse. Much like a misunderstood lad who adopts a life of crime after meeting more hardened youths in reform school, it seems that a perfectly good battery can be spoiled by other, more delinquent cells in proximity. Bad personalities rub off. Imagine if all the batteries in the world banded together under one type-A personality battery (a triple-A making up for size?) bent on global domination. Chances are good it could happen here in Africa, which has bred despotic dictators since the colonial masters showed the Africans how it’s done. Then what? Look out is what. I could scarcely imagine the outcome, mainly because like most people I don’t think much about batteries until they die, at which point I curse them and move on.

By the fall of 2009 this whole battery personality business had become a big issue for Burro. Jan and Whit first started getting indications about battery problems in the summer—customers, the agents said, were complaining about noticeably shorter battery life. “I am worried,” said Kevin one day after his route. “The agents say they don’t want to go out and sell because they don’t want to hear the complaints.”

This was puzzling because in tests back at the office, the batteries seemed to be doing fine. Granted these early tests were not the most scientific; without sophisticated electronic analysis equipment, testing basically involved running batteries through a discharge cycle (a feature on the chargers that simply reverses the current flow) and timing how long it took. The batteries were rated to deliver 2.3 amp-hours of current, which in battery-speak is expressed in one thousandths of an amp-hour (one milli-amp-hour), written like this: 2300mAh. In practice, said Whit, it was more reasonable to expect around 1800 mAh per battery at this stage in their life cycle. (You could compare this to the difference between a car’s official gas mileage rating and its actual mileage in traffic after a little wear and tear.) Since the chargers had a metered discharge rate of 300 milli-amps per hour, it ought to take around six hours to completely discharge a healthy battery.

Which it did.

So the batteries seemed fine—but to be sure, Jan also tried running down fresh batteries in a variety of flashlights and radios, and timing the results. All these tests had begun as soon as we arrived in June, and the batteries seemed to be holding up well, certainly as well as Tiger Heads. Still, the complaints continued. What was going on? What kind of weird personalities were we dealing with?

The battery was invented in 1800 by Alessandro Volta, a physics professor in Como, Italy. Volta had studied the experiments of Luigi Galvani, a Bolognese physician who observed that a frog’s leg twitched when connected to two dissimilar metals. Galvani thought the phenomenon was due to what he called “animal electricity,” but Volta realized that the moisture in the frog’s leg was actually facilitating a chemical reaction between the two metals that caused a transfer of electrons—an electrical charge. Put another way, chemical energy was being converted into electrical energy. Volta refined the process, using brine-soaked blotter paper instead of a frog’s leg to create a steady electrical current between plates of copper and zinc stacked up within a glass tube. His battery, known as the Voltaic pile, was itself of little practical value. It was large, fragile, and prone to internal leakage of the brine (known as the electrolyte), which caused short circuits. It also had a tendency to generate bubbles of hydrogen gas which, besides being explosive, increased the battery’s internal resistance and limited its useful life to about an hour.

But the principle was revolutionary. When you consider that the electrical generator was not invented until 1831, by the British physicist Michael Faraday, Volta’s battery represented the first form of continuous electricity (as opposed to static charges) known to man. Today—at least in the modern West—we think of batteries as a convenient supplement to generated electrical power, yet in fact they came first. By the time Faraday was demonstrating his first electromagnetic generator, incremental improvements on Volta’s design had already led to batteries with steady currents capable of lighting rooms, albeit not for very long.

And then something special happened. In 1859 the French physicist Gaston Planté replaced the copper and zinc electrodes of the Voltaic pile with alternating plates of lead and lead oxide. Then he used an acid solution as the electrolyte. The acid interacted with the two forms of lead to generate a sustained current unlike any previous battery. Planté’s lead-acid battery had genuinely useful applications; his 150-year-old design was essentially the same as the battery in your car. But his findings went beyond inventing the first practical battery. Planté also realized that after the lead-acid battery ran down (converting the two types of lead into lead sulfate), it could be brought back to life by reversing the process and feeding a current back into it. Thus in one swoop, Planté had also invented the rechargeable battery.

The 1880s saw the development of dry cells (made of carbon and zinc), which made it possible to produce small, portable batteries. Dry cells are not totally dry—it’s a relative term compared to the watery liquid in lead-acid batteries. They do, however, leak a gooey, corrosive electrolyte when run down very low. In 1898 the National Carbon Company introduced the first D-cell, a carbon-zinc battery whose direct descendant is the Tiger Head sold in Ghana today.

A Swedish inventor named Waldemar Jungner created the first rechargeable nickel-cadmium battery in 1899, but it was expensive and impractical as it required venting of internal gases. It wasn’t until the late 1940s that sealed NiCd batteries (which recombined the internal gases) were developed, opening up the consumer market for rechargeables.

NiCd batteries proved to be workhorses that dominated the rechargeable market for decades. They are relatively inexpensive, tolerant of deep discharge, can handle high loads (such as those required for power tools), recharge quickly, store well, and last for more than a thousand charge cycles. On the downside, NiCds have low energy density, meaning power comes at a cost of weight and size. The batteries also develop crystals on the cell plates that reduce charge capacity over time—that familiar phenomenon called “memory” that can be especially problematic if NiCds are repeatedly charged without having been fully discharged. Finally, cadmium is extremely toxic in the environment, complicating transportation and disposal of NiCd batteries.

The next major battery improvement was the development in the 1980s of the nickel-metal hydride (NiMH) battery. NiMHs have several advantages over NiCds, namely far less memory effect, as much as 40 percent higher energy density (meaning smaller size for equivalent power), and only mildly toxic ingredients, greatly simplifying disposal and transportation. But there are trade-offs: NiMHs don’t last nearly as long as NiCds (you get roughly three hundred charge cycles); they can’t take high loads as well (making them less suitable for power tools); they are less tolerant of deep discharge; they take longer to charge and generate more heat while charging; and they have a greater propensity to “self-discharge”—that is, they lose their charge relatively quickly during storage. Oh, and they also cost about 20 percent more than NiCds, although the price difference seems to be narrowing as NiMH technology has improved and come to dominate the consumer market.

Given all the disadvantages associated with NiMHs, you might think the old standby NiCds would be the way to go in Ghana. But Whit ruled them out for one simple reason: because of the NiCd’s low energy density, it was impossible to get the power of a D battery in an AA-sized cell. This was a deal-breaker because a big part of Burro’s business model was the two-for-one offer: an AA battery that slips into an adapter for D-powered devices. Then there was the environmental issue: “Do I want to be the guy bringing tons of cadmium into Africa? I don’t think so,” said Whit.

NiMHs, on the other hand, were environmentally friendly and dense enough to deliver the big power in a small package that Whit needed. From the beginning, they were the only real choice.*

Whit arrived from China in July with an array of geeky testing gear—a battery analyzer with a serial port interface to his laptop, and a regulated DC power supply that could be adjusted to deliver a constant source of either amps or volts.† Using these machines, he could run calibrated loads on batteries to mimic the load of any device, such as a flashlight or a radio. Then he could monitor how long it took for the battery to run down—the point where the voltage dropped so low as to be effectively useless. The analyzer plotted the results as a graph on his laptop.

Whit connected a cheap Chinese LED flashlight—the kind many Burro customers use, bought at the market in Koforidua—to the DC power supply unit, using alligator clips. The flashlight was meant to be powered by two 1.5-volt D batteries, so he set the power at three volts. The beam was clear and bright. Then he dialed the voltage lower and lower, watching the light grow increasingly dim. At one volt (half a volt per battery), the flashlight gave off only a faint glow. We turned out the room light (it was nighttime) and could barely see ourselves in the orange cast. It was dimmer than a candle. “I would argue that’s the bottom end of useful light,” said Whit. “I mean, it’s beyond any functional task lighting; you couldn’t read by it. But I suppose you could argue it still works as a night-light. Basically it’s dead.”

“Agreed,” I said.

Knowing that the flashlight became useless at one volt, Whit could now measure how long various batteries could reasonably power the light—that is, deliver more than half a volt (considering there are two batteries) at the constant current being drawn by the bulb. He began by connecting a new Tiger Head to the battery analyzer, then entered the following parameters on the laptop interface: start at 1.5 volts and draw down steadily at the flashlight’s current load until .5 volts. “So we’ll time that and see how it does,” he said, “then we’ll do the same with a Burro battery starting at 1.2 volts, which is its top-rated voltage.”

By the next afternoon, we had the results. Both batteries had comparable duration: the Tiger Head dropped to half a volt in six hours and thirty-eight minutes; Burro hit the same target in six hours and fifty-seven minutes—about twenty minutes longer. But the big difference was in overall performance, as plotted on two graph charts. The Tiger Head was obviously brighter at first, since it starts out delivering 1.5 volts compared to Burro’s 1.2. But after just forty-eight minutes, the Tiger Head had dropped below 1.2 volts. By contrast, the Burro kept running at 1.2 volts for more than six hours—virtually its entire life. In other words, Tiger Head was brighter for forty-eight minutes, and then Burro outshined it for five more hours. The graphs made the difference clear: Tiger Head’s power drain charted a steady decline from the get-go, but Burro’s graph was essentially flat for six hours—dropping off rapidly at the end. Burro truly delivered on its promise of more power.

(Whit later learned that the popular LED-powered flashlights were not drawing a constant current but were in fact drawing less and less current as the voltage decreased. Recalibrating the test with that information showed that the Tiger Head–powered device was brighter for about six hours, then Burro was brighter for about thirty hours, at which point Tiger Head hobbled along at one tenth its original brightness for another couple of days.)

That was good news, but it didn’t explain the complaints about bad batteries. Obviously not every battery was performing up to snuff. Whit started running batteries through the analyzer and found that on average, the batteries had lost about 20 percent of their original capacity. This was not too surprising—it’s what happens to rechargeable batteries over time, and some of these were nearly a year old. Still, the drop-off was more than Whit had expected. “The business model is based on batteries lasting three years—two years at least,” he said ominously.

“What do you think’s frying ’em?” I asked.

“Could be a lot of things. Some of the original chargers we had might have damaged them; they were putting out way too much power. It didn’t help that the second load sat in a can for five months.” What he meant was that the shipment from China had been held up at port in Durban, South Africa, due to an incompetent shipping agent; the batteries spent months in an airless metal container. Heat can cause permanent damage to NiMHs.

“And they could just be low-quality to begin with,” said Whit, who was up at five every morning to email China, looking for a better battery manufacturer, among other product sources. “And frankly, I think usage patterns could be hurting them. People are using this fairly sophisticated battery in all these dumb devices, and they’re just running them until they quit working—which is how they use throwaways. Some are coming back at zero capacity, and NiMHs don’t like to be run down all the way to nothing. It’s best if you leave some capacity in them. In some cases I think these things are getting run down until they reverse polarity, which is really bad.”

Whit began a reconditioning program for batteries that had been returned as faulty from the field. He stayed up for hours after dinner, sitting at a small desk in the battery room, discharging bad batteries, then applying small currents to jump-start capacity before charging them again. Mostly it worked—the reconditioned batteries performed as well as average and went back into service. But some were beyond repair, or even understanding.

“Max, check this out.”

I looked over Whit’s shoulder at the laptop. “So I just reconditioned this one, and it’s showing good capacity. But when I put any kind of load on it, it drops right off a cliff, down to nothing.” He pointed to what indeed looked like the profile of a cliff on the chart. “Then, when I put a charge on it, instead of gradually climbing, it spikes like a rocket, then it drops as soon as I take the charge off. I can’t get any accurate capacity reading, and the power curve is just nuts. And the really scary thing is, when I test it in the little hand tester, it reads fine. But the customer sticks this thing in a tape deck and it runs right down. They seem to have capacity, but they don’t produce current flow. What the hell does it mean?” said Whit.

“You’re asking me?”

“Only rhetorically, because you’re an idiot. Frankly, so am I. I only know enough about batteries to be dangerous, and I have no clue what this means.”

“How many are doing that?”

“I don’t know yet.”

“You’re so fucked.”

“Only if I can’t identify them. Right now I’m just trying to stem the damage to the brand and pull them out of circulation. I’m working on a quick, production-oriented approach to culling bad batteries.”

“English, please.”

“I’m starting with Jan’s idea of using the discharge function on the chargers—setting a timer and pulling any that discharge fully in under five hours and putting them in a bin for reconditioning later. The ones that last over five hours, I’ll put on the analyzer and run a medium-high rapid-load test to make sure they can pull a good amp out and still put out at least 1.1 volts. If it passes that test, I’ll put a blue mark on it and send it into the field. Any that don’t pass get shitcanned. When the batteries come back from the field, any that don’t have a mark I’ll run through the test. Eventually we’ll get every battery in the field through this level of certification. What stinks like a dead animal?”

“A dead animal. I bought an antelope hide in the market today. A bushbuck. I don’t think it’s fully cured.”

“That’s disgusting. Where is it?”

“I put it on your bed to air out.”

“You asshole!”

“Speaking of bed, I’m turning in. Good luck with those batteries.”

In fact, if it were my company, I would have locked up the office, thrown away the key, rolled up my antelope hide, and bought a plane ticket home. But not Whit. His nights in the battery room grew later and later. Surrounded by buckets of green Burro batteries and racks of blinking chargers, he worked, bent over his testers and coils of wire, like a mad scientist. Sometimes I could hear him talking to himself—grunting and sighing over his Sisyphean toils.

“How’s it going?” I asked him one night around ten, after my evening shower—the only time of day you could get clean and hope to stay dry for more than ten minutes in the oppressive humidity.

“Pretty good. I’m getting a handle on this. It looks like about ten or eleven percent of our stock is failing.”

“Wow. That’s not good.”

“Well, it’s certainly not sustainable. I mean, overall we’re hearing customers are very satisfied, but long-term, if you’ve got ten percent of your product not performing, that’s insanely high. It’s not gonna lead to ninety-eight percent customer satisfaction, let’s put it that way. And the problem is, the people it impacts the most are our best customers—the guys with these massive high-powered radios and tape decks that use lots of batteries. You know, these culls can run flashlights no problem—put a little fifty-or hundred-and-fifty-milli-amp load on them and they’re fine. But those boom boxes pull much higher loads; they take six or eight batteries, and it only takes one bad one to shut it down. So let’s say there’s a one in ten chance he’s got a stinker; if he changes batteries twice in an eight-battery device, he’s almost certain to get one stinker. The radio shuts down, and he thinks they’re all stinkers.”

“Ouch. So you get rid of the stinkers, but what’s the long-term fix?”

“Well, chipped batteries would solve the problem.”

“Chipped?”

“Add some circuitry to the battery that cuts it off at nine hundred millivolts, so people don’t run them down so low. And if you did that, you could have circuitry that prevented charging in unauthorized chargers, which would eliminate theft issues once we expand to big cities. For that matter, a chip could track cycle counts, capacity, total power in and power out—basically get a running health report. We’d probably have to order like a hundred thousand of them, so it’s big money. And I don’t even know if any of this is possible in a double-A; there might not be any room for the circuitry. I’m pretty sure you’d need another contact point too, for data. To my knowledge nobody else is using rechargeable double-A’s in a rental business model, so I doubt if anybody has even tried to make a smarter double-A battery. But I don’t know.”

“Hold on, Einstein. Let’s say you can chip these batteries. And let’s say some woman is out hunting snails in the bush at midnight, and suddenly her flashlight battery clicks out when it hits your little voltage cutoff. She’s stranded in the jungle, with the pythons. Oops! Bad idea.”

“I hear you. But the thing is, by the time that battery’s only pushing nine hundred milli-volts, it’s practically dead anyway. It’s just not giving her much light at all, certainly not for walking around the bush at night. I don’t think she goes out to the bush with a flashlight that weak to begin with. And the time for an LED flashlight to go from nine hundred to four hundred milli-volts is less than ten minutes, so it’s not like the client is getting a lot less use. The client utility at that point is effectively nil.”

Batteries weren’t Whit’s only worry. During a company meeting the next day, Jan and Whit brought up another looming concern: the potential for counterfeit exchange coupons. The first coupons were simple black-and-white A4 printouts from Burro’s HP Officejet, which were then cut into individual coupons and stapled together. We knew that was asking for trouble, but it seemed like an acceptable risk for the first test market in Bomase, which everyone was anxious to get going. By mid-July, as the pay-go (short for “pay-as-you-go”) offering expanded across the test region, we had added a multicolored hand stamp with the Burro logo.

“Fortunately the value of a coupon is fairly low,” said Jan, “so the cost of photocopying and cutting may be prohibitive to a thief, but we need to take steps to make it more prohibitive.”

“I can see all kinds of solutions long-term,” said Whit, “printing in China with the Burro color, adding a watermark, finding a local printer who specializes in security printing. But we need something in three days.”

For now, Jan and Whit decided to engage the services of a local printer, using colored ink. That came with its own dangers, namely the potential for a dishonest employee at the print shop to take advantage of the relationship. “If we serialized the coupons, that would be a higher bar,” said Whit. “Adam, find out what the incremental cost is for that. And I’m thinking if we put a wavy pattern in the background it would be harder to pull out the stamp image and re-scan it. And maybe the stamp could be in a blue ink that doesn’t photocopy. Let’s see what all this does to our costs.”

On the road between Nkurakan and Amonfro, about a twenty-minute drive from our office, lived an Ewe fetish priest named Torgbe Ahluame. Fetishism is an ancient belief system that West Africans call Vodun, an Ewe word from which the word voodoo derives. It revolves around one god but with many “helper” deities or spirits—frequently the spirits of ancestors, who exist alongside the living. These spirits are manifested in talismans like animal parts and sculptures—the fetishes around which worship takes place. Voodoo and other fetish religions are still practiced in much of Africa, thriving alongside Christianity and Islam.

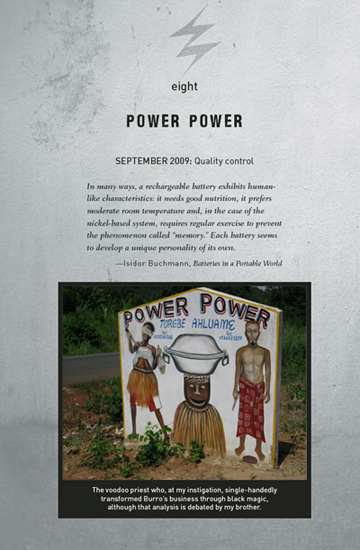

Torgbe’s site was impossible to miss, marked by a six-foot-square painted concrete sign that said POWER POWER on each side, along with his name and two mobile phone numbers. One side of the sign featured a pair of African mermaids with long, straight black hair that tumbled and curved around their exposed breasts. One of the mermaids was holding a white dove in her left hand and a long, straight knife in her right; the other was admiring her visage in a hand mirror. On the other side of the sign were painted two men. One wore a traditional grass skirt and seemed to be dancing, or writhing in ecstasy; the other had a kente robe around his waist and was standing erect. Both were brandishing knives. Between the two men was a bizarre composition whose iconography I can only guess at: a figure in the shape of an African drum, but with a human face and cowry shells for eyes, was balancing on its head two large metal bowls—the type African women carry on their heads to market. The top bowl was inverted over the lower bowl, as if to cover something inside. And here was the strangest thing: the rims of the bowls were clamped tightly shut with a pair of massive padlocks.

I took a picture of the sign and showed it to several Africans I knew well. None could say exactly what it meant—it didn’t appear to be any conventional symbolism—but the general speculation was that it conveyed great power inside the bowls that had to remain under lock and key.

I wondered what kind of power this priest could unlock from the spirits. “Hey, Whit,” I said casually one afternoon, “what say we take some of these bad batteries and go see the fetish priest.”

“The fetish priest?”

“You know, the Power Power guy—up on the Amonfro road.”

“You’re joking, right?”

“Not at all. Maybe he can put more power into these batteries. Look, you said yourself you don’t understand what the hell is happening to the bad ones. They go up, they go down, it makes no sense. So maybe we need some voodoo. That guy who wrote the battery book says every battery has a personality all its own. Maybe this priest can tap into that.”

“Have you been drinking?”

“Of course not. Let’s go check it out.”

“I will do no such thing.”

“Oh, come on! What can it hurt?”

“Human sacrifice is what can hurt. I hear it hurts a lot.”

“They don’t do human sacrifice. Not very often.” I had heard lurid stories of fetish priests demanding blood sacrifices (called mogya sika duro in Twi) from customers who came in search of riches. In most cases, blood was obtained relatively harmlessly—from the menses of a woman, or a small cut—but in some parts of Africa, albinos have been murdered at the behest of fetish priests. Such crimes are rare; fetishism is broadly accepted in Ghana, and you don’t read about humans being sacrificed left and right. Still, in 2008 Ghanaian police arrested two men for selling a sixteen-year-old boy, who was being offered for body parts to fetish priests. At last report the police were having a hard time locating the boy’s family—raising suspicions that relatives had been complicit in the sale.

“I have no idea what they do, and I don’t feel like finding out,” said Whit. “Those guys are scary.”

The next day, I asked Kevin what he thought. “Oh, don’t get involved in that,” he said gravely, shaking his head.

“Why not? What could happen?”

He thought for a few seconds. “You will maybe get into something you had not expected. It will cost you.”

“You mean money?”

“That, and possibly more. Once you visit the fetish priest, it is hard to remove yourself. That is all I can say.”

This was starting to sound like heroin. I told Whit that if he didn’t come I would go by myself. I was bluffing: I had no intention of going alone. One blazing hot Sunday afternoon he finally relented. “Okay, I’ll go, but only to make sure you don’t do anything incredibly stupid that jeopardizes our business,” he said. “I’m not saying anything, and I’m sitting close to the door.”

An hour later we pulled into Power Power, partially hidden behind a bamboo fence. At first it looked like a typical rural family compound: metal-roofed square clay huts to the left and right were bunted with the usual assortment of drying laundry; children played under the shade of wide eaves. But straight ahead was something out of the ordinary: two more connected huts, their entrances veiled in curtains and shaded under eaves, were painted with more colorful scenes of knife-wielding mermaids and priests; these were obviously the temple rooms. The children shouted “yevu!”—Ewe for white man. A young woman approached. I asked for the priest and she led us into one of the family huts off to the side, where we sat in a bare room and waited for our consultation. On a small table rested three intravenous vials of ampicillin, a strong antibiotic. “There’s your ‘magic,’” said Whit with a sneer.

“Shhh, he’s coming.”

“Good afternoon. I am Torgbe Ahluame.” I was expecting a wizened old sage in a robe, but the figure who stepped through the doorway was an athletic man in his early thirties wearing gym shorts and a Nike T-shirt. Behind him followed a slightly younger man whom I took to be the sorcerer’s apprentice. Both shook hands with us, sat down, and smiled.

“So?” Torgbe asked.

I told him about Burro and the problems we were having with some of the batteries, extracting two bad ones out of my shirt pocket. “We need more power in these batteries,” I concluded, handing them over.

“Not just these, but all of them,” Whit whispered in my direction.

“I thought you weren’t talking.” He glared at me.

“These and many more,” I added. “These are just two examples.”

Torgbe held the batteries and pondered the problem for about two and a half seconds. “It can be done,” he ruled. “The spirit can help you.”

“Oh, thank you, sir,” I said respectfully, bowing my head. “What must we do?”

“It will require alcohol,” he replied.

“Ah, so we should go buy alcohol and return?” I asked, mentally kicking myself for not having thought of that. Of course it would require alcohol.

“No,” said the apprentice. “We will take care of it. Give us two cedis and we will bring the alcohol for the spirit.” I unfolded two cedi notes from my pocket and handed them over, relieved that the price of entry was so reasonable. “Please follow me,” said the apprentice as Torgbe disappeared into another room.

We stepped back into the sun and crossed the dirt yard to the first of the two temple rooms. “Remove your shirts and shoes,” he said at the entrance. Whit and I glanced at each other. The apprentice was now holding a knife very similar to those in the paintings. We disrobed and entered the temple.

The windowless room was dark and stuffy. The only light came from a candle burning in a large metal bowl on the tile floor, which was mostly covered by animal hides. From the glow of the candle we could see more wall paintings. One showed a bearded Old Testament priest with his hand on the forehead of a prone man who was obviously sick. Next to that was another buxom mermaid, this one I think modeled after Charo. On the next wall was a bearded man sitting under a tree with a snake in the branches. Over to one side, the room opened into a small alcove, which was hidden from view by a gauzy curtain. Next to this alcove was a carved wooden bust of a woman almost completely covered in hardened drips of candle wax—the fetish.

We sat in plastic chairs next to the man with the knife, sweat pouring down our exposed chests. Soon Torgbe entered. He was now shirtless himself, with a muslin wrap around his waist. He sat in front of the gauze curtain. He had a bottle of schnapps. “The spirit has requested three hundred to be summoned,” he said.

“Three hundred cedis?” I asked, fairly choking.

“I think he means three hundred thousand old cedis,” said Whit.* This confusion, combined with the fact that English-language numbers could be difficult for uneducated Ghanaians to master, often complicated financial negotiations. “Is that right?”

“Yes,” said Torgbe.

“So you mean thirty new Ghana cedis?” I said.

He thought for a minute, doing the mental math. “Yes.”

“Wow,” I said, peeling off three ten-cedi notes, about twenty dollars, from my bankroll. I handed them to the assistant, who passed them along to Torgbe, who stuffed them into a small woven basket. Then he draped the curtain over his head, rattled a shekere (a percussion instrument made from a gourd covered with cowry shells), and began chanting what sounded like gibberish in a strange tongue. He poured a shot of the schnapps into a small plastic cup, recited some invocation, and poured the liquor over the wax-covered fetish. This was presumably the offering to the spirit. He poured another shot and downed it himself. His apprentice took the bottle, poured a generous shot on his own account, and then poured one for Whit and finally me. The liquid was strong and coarse, and I had to choke it down. I felt bad for Whit, who had been suffering an all-too-common bout of intestinal dysfunction; the last thing I’m sure he needed was a long slake of moonshine. But it seemed clear that to refuse the alcohol would anger the spirit. Plus we had paid for it.

The libation completed, Torgbe was ready to engage the spirit. His face was still concealed behind the curtain. There was more shekere rattling, lots of strange yelling, and suddenly a cloud of “smoke” that smelled remarkably like talcum powder filled the air around the curtain. I was beginning to feel like Dorothy meeting the Wizard of Oz. And then the spirit spoke.

Or I should say, squeaked. The all-powerful spirit, it turns out, had a voice closely related to one of those plastic dog chew toys that squeaks when you squeeze it. And the spirit apparently had a lot on his mind, because the squeaking went on for some time. I looked at Whit. His eyebrows were approximately on the ceiling, and his jaw was stretched tighter than a drumhead. He was trying his best not to roll over laughing.

“The spirit says you are welcome,” said Torgbe, emerging briefly from behind the curtain.

“Please tell him thank you for us,” I replied.

Torgbe drew the curtain closed again and chanted some more, which was followed by more spiritual squeaking.

“The spirit says he can give the batteries much power,” confirmed Torgbe, again pulling aside the curtain. “But there must be a sacrifice.”

“Of course,” I replied.

“We must kill a cow,” he said, and at that moment his apprentice demonstrated by drawing the knife close to his own throat. “From the blood will come the power. Also three bottles of alcohol and fifty million cedis.”

“Fifty million cedis?” I asked. “So that’s, let me see … five thousand new Ghana cedis?”

“Yes.”

“Five hundred, right?” suggested Whit hopefully. “You mean five hundred new cedis.”

Torgbe, whose English was rudimentary, seemed confused. (We learned later that he was in fact Togolese, although his French was also weak.) He reached behind the altar and withdrew a ruled student notepad and a ballpoint pen. On the pad he wrote the numeral five, followed by four zeros—no commas or decimal points. “That is how much,” he said. So did he mean fifty thousand? In old or new currency? Now it was our turn to be confused.

“Can I see the pad?” asked Whit. He took the pen and started writing. “So ten thousand old cedis equal one new cedi, right?” He wrote down the equation. “And one hundred thousand old cedis equals ten new cedis, okay?” He wrote the numbers below the first set.

“Right,” said Torgbe, looking on closely.

“Okay. So one million old cedis equals one hundred new cedis, yes?”

“Yes.” Whit wrote down the numbers.

“Now. That means five million old cedis is the same as five hundred new.” He wrote it down.

I was getting slightly embarrassed for the spirit, who was waiting patiently behind the curtain while this currency conversion played out. “So the spirit is asking for five hundred new Ghana cedis, right?”

“No,” said Torgbe firmly. “Fifty million old, five thousand new.”

“Really?” said Whit.

“And a cow.”

“Oh, the cow is not included in the price? How much is a cow?”

“Maybe three hundred cedis,” said Torgbe.

“Old cedis?”

“New cedis.”

“Wow,” I said. “I don’t have that much, and I’m not sure I can get it.”

“When can you come back?”

“Well, I can come back any day, but I don’t think I can get that kind of money.”

“You will check and come back tomorrow,” Torgbe commanded. I was starting to see what Kevin had meant when he said it’s hard to extricate yourself from these guys. “Now, we will pray for you. Come.”

Torgbe and his man Friday led us out of the hut, back into the glinting sun, next door into the other windowless temple room. We stepped into the dim light and almost fell over from the stench of rotting flesh. After our eyes adjusted to the dark, we saw, in the center of the floor, a large pile of cow horns and jawbones, still slippery with dark, coagulating blood. In a far corner I made out nine African peg drums of different sizes, stacked up. On the other side was a high altar topped by several wood sculptures of African priestesses and other traditional figures. In the center of the altar, piled almost to the ceiling, was another gruesome tableau of rotting animal bones—at least I hoped they were animal bones.

“You must kneel,” said Torgbe, pointing to a goat hide in front of the altar. I got down on my knees over the blood-matted fur, trying to breathe through my mouth so as not to vomit from the vile odor of the room. “The spirit needs twenty cedis.”

“I have only ten,” I said.

“Okay.” Clearly the spirit, as channeled through Torgbe, was negotiable.

I fished out the note. Torgbe set the crumpled bill on top of the cow bones. He chanted for several minutes. “You may go now,” he said.

“Can we have our batteries back?”

We took our batteries and left, but not before Torgbe’s apprentice got my cell phone number. We drove out, past the bamboo fence, past the sign with the mermaids and the knives, and we did not stop until we got home to Koforidua.

“You asshole!” said Whit, speeding into town.

“What?”

“What?” he repeated in a mocking falsetto. “This guy’s on our route, and if we blow him off he’ll be pissed, and he’ll totally fuck my business—not with his lame Donald Duck spirit but in real ways, like telling people not to buy the batteries. You asshole! This is all your fault. You need to talk to him and figure out how to get out of this gracefully. Maybe the spirit will need five hundred cedis, I don’t know, but you need to figure it out before you slink out of here, asshole.”

“I’ll talk to the man tomorrow.”

That night, the power went out. Torgbe called me twice over the next few days. I told him both times that I didn’t have the money. I never went back.