In September Burro had its first birthday and was still not breaking even; far from it. In fact, the trailing thirty-day revenue of about two hundred cedis was roughly one tenth of what Whit called his “burn rate” of two thousand cedis a month—another way of saying negative cash flow.* On the bright side, growth was phenomenal: revenue was doubling every two weeks. The new offering was catching on, so it appeared to be a question of conscripting enough agents, getting them trained, and getting the word out. Whit and Jan crunched the numbers and figured break-even (and possibly modest profit) would happen when the branch had roughly one hundred agents renting one hundred batteries each, so “100/100” became the rallying cry. Almost all of Burro’s “corporate” energy in late summer was focused on signing new agents. Every morning the staff split into teams and fanned out across the region. One day it might be Jan and Rose in the truck, heading up north toward Bomase, while Adam and Whit took the Kia Pride (another used car Whit had bought, known in the United States as a Ford Festiva) south, through towns along the road to Mamfe, a busy junction town on the Akwapim Ridge just before the road descends into the dust and chaos of Accra. Kevin, meanwhile, spent a lot of time managing the twenty-six agents still working under the old, monthly rental system, a job that included preparing them (and their clients) for conversion to the pay-go plan in early September. On some days Adam would stay in the office and work on the books while Kevin and Whit, or Whit and Rose, or Jan and Kevin went off on the routes. It was a rotating chain of teams, everyone vying for time in the two vehicles because the alternative was taking tro-tros. Sometimes we would get stranded in a remote village with no tro-tros or taxis, and then we would walk, down dusty roads that traversed cocoa farms, thick bamboo stands, and high, grassy plateaus.

Sometimes we saw snakes, mostly small neon green varieties—almost Burro green—that probably weren’t poisonous, but we didn’t know, so we kept our distance. Once a python—a small one but a python just the same—slithered lazily across the trail in front of us. Had a local farmer been with us, he would have surely hacked it apart with his machete. Visitors often find this brutal, but snakes in Ghana kill people in very ugly ways. The Armed Forces Pest Management Board of the U.S. Department of Defense lists twenty-four venomous snakes in Ghana, including, besides pythons, many varieties of cobra, viper, adder, and mamba. Some carry venom that is hemotoxic—causing internal bleeding and death—but most are neurotoxic, shutting down brain functions like breathing and heartbeat. Death in either case is agonizing, and not fast enough. Some venomous snakes won’t actually kill you; they just cause “tissue necrosis” (in the words of the Defense Department), requiring amputations. These are not anomalies. I couldn’t find numbers for Ghana, but it’s estimated that perhaps a thousand people every year die of snakebites across Africa, and many more thousands are wounded and maimed. Potentially deadly encounters with snakes are quite common in Ghana, and there is no 911, no ambulance to rush you to the ER for some antivenom. If you are in the bush in Ghana and you are bitten by an Egyptian cobra, you will die of respiratory failure within five hours.

Watching carefully for snakes, I tagged along with one or another of these groups (including the tro-tro excursions) on most days. We would pull up in a new town, survey the market and the shops, unload our plastic tubs full of batteries and flashlights, draw a crowd (not hard for a white person in these outposts) and start walking and talking—looking for the important people, the opinion leaders, maybe even the chief or at least a shopkeeper with a good reputation. Kevin and Adam and Rose would talk in Twi or Ewe or Ga; Whit and Jan and I would embellish in English (and sometimes French if the people were from Togo or Benin). Whit and I would make funny faces at the children who crept up to stare at us; they would run away squealing in laughter as we bared our teeth and shook our arms and pretended to be monsters. Then we would open our plastic bins and pull out our wares and demonstrate our batteries. Villagers would leave and return with radios and flashlights, and we would take them apart and pull out leaky Tiger Heads, sanding down rusty terminals (with scraps of sandpaper kept in our road kits) and inserting new Burro batteries. “Ahaahh!” they would say in appreciation as we turned on the radio and blasted them with their favorite station—hiplife or reggae or news or talk or soccer, whatever. “Ahaahh!” they would say again. And we would smile and say to the growing crowd, “Who would like to start saving money on batteries today?”

The towns had strange, exotic names like Huhunya, Agogo (as in “whiskey-a-go-go”), Tinkong, Nkurakan, Beware (Beh-WAH-ray), and Bosomtwi (Bo-SUM-chwee). But after a few weeks they could as well have been Moline, Youngstown, Danbury, or Duluth. After a couple of months they all started to blur together—an endless brown palette of mud huts, fire pits, flinching dogs, fly-covered goats, peanut stews, tattered and stained laundry draped limply over frayed nylon lines, and half-naked children with their ceaseless cries of “Obruni! Obruni!”

“That’s my name,” I’d say, “don’t wear it out.”

“Obruni!”

“Wo te brofo, anaa?” I would ask. Do you speak English?

“Yes,” they would say.

“My name is Max. What’s yours?”

“Obruni!”

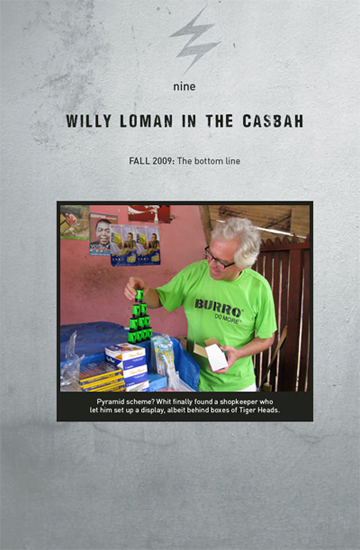

The daily word games with children devolved into a certain sameness, but at least it was fun to make them laugh. Far more tedious was the sales pitch. There were days when I felt if I had to listen to the battery spiel one more time I would crawl out of my skin, slither under a rock, and renounce my citizenship in the human race. But if you’re going to be a good salesman, you have to get excited about your product every day, with every customer. It’s new to them, no matter how familiar it seems to you. Before coming to Africa, I joked about finding Willy Loman in the Casbah. Now I was becoming him.

Almost every week brought a gong-gong, crucial for building brand awareness and acceptability in villages where new products, or better ways of buying existing products, were virtually unknown. The format had not changed since the first gong-gong in January—a formal introduction to the chief and elders, sometimes followed by a Christian prayer in the local language, then our pitch.

Not that any two gong-gongs were quite alike. In Mangoase, a cocoa-growing center of three thousand voters, the gong-gong man insisted that everyone speak through his new, out-of-the-box megaphone. This seemed of dubious necessity given that only nineteen citizens showed up for the gong-gong at the town well, and we could hear one another just fine without amplification. Maybe he felt a jolt of technology would help revive his town, which was long past its prime. Mangoase was once an important railway depot on the line between Accra and Kumasi, and its hilly streets were lined with stately colonial buildings. But the trains stopped running years ago—the tracks reverting to bush—and the only roads into town were washed-out dirt tracks. The colonial buildings were now faded and crumbling; despite an impressive public market basilica, Mangoase had the claustrophobic melancholy of a dying New England mill town.

Unfazed by his community’s wounded pride, the gong-gong man jumped energetically from speaker to speaker with his megaphone, as if working the audience of a TV game show. Most of us were largely unfamiliar with the operation of a megaphone, and its employment by untrained hands presented no small amount of danger. If the person next to you was speaking, you had to duck when he turned his head, to avoid getting whacked by the device or, worse, suffering permanent hearing damage from a point-blank acoustic blast of the speaker—powered, I might add, by Burro batteries.

The pitch for those batteries had evolved under the new pay-go system. No longer were batteries “fresh, anytime you want,” which reflected the monthly rental system of unlimited free recharges. Now our mantra was “better battery, half the price”—since a two-cedi Burro coupon book yielded sixteen individual refreshes, versus buying eight Tiger Heads for the same price. (To simplify the offer, the 1.50-cedi coupon booklet was changed to one cedi, which bought seven refreshes.) Whit and Jan perfected the pitch over several weeks, trying to boil it down to simple phrases, easily understood. They identified six reasons why Burro was a better battery:

1. Half the cost

2. More power

3. No-leak guarantee

4. Two in one (AA and D, using the adapter sleeve)

5. Cleaner and safer

6. First charge is free (you pay only deposit first time)

It seemed clear enough, but when Kevin, Rose, and Adam gave the pitch in one of the country’s native languages, we couldn’t understand what they were saying. And it often seemed like their spiel was taking a long time, even factoring in the consonant-laced African vocabularies. But over time we got better at recognizing their phrases, in part because many modern words have no local linguistic equivalent and are simply repeated in English—like battery, although in Twi the phrase we most heard was battery-nie, which means “these batteries.” And apparently there is no way in Twi to say “better for the environment,” because Kevin always said that in English.

After the pitch came questions and demonstrations. Then Whit would say, “So who wants to be the first person to start getting batteries for half the money?” Someone would step forward with a few wadded up cedi notes in his hand, and we would lead the crowd in applause.

Or not. Sometimes no one came forward. Sometimes no one showed up at all. One Friday in late August we arrived at two different gong-gongs in far-flung villages that somehow never got organized. This happened a lot, sometimes after driving for an hour down a road that was little more than a footpath. Sometimes the road itself ruined the gong-gong. One day, Jan and Rose were driving on a back road in the Kia when an exposed tree root punctured the sidewall of a tire. They jacked up the car and put on the spare—which was flat. They walked over a mile in the punishing sun to a village, where a man with a bicycle pump accompanied them on foot back to the car. They got home late, well after dark, hungry and tired. This sort of thing happened on an almost weekly basis.

Occasionally the gong-gong no-shows were understandable: someone had died in the village, and funeral arrangements had to be made quickly, out of respect and, in places with no refrigeration, sanitation. But sometimes the excuses boggled us: “It is cloudy, so the people lost track of the time.” Never mind that virtually every adult in the realm had a cell phone with a clock. Time is simply not tracked precisely by people who live by the sun and the planting seasons. When rural Ghanaians do think about specific times, it is usually in the past tense—as in the time of the ancestors. Time as a future concept is rarely considered. Meetings will happen when they happen; what is the point of worrying about it? Likewise it is nearly impossible to get a Ghanaian to give you a realistic distance between villages. The next village is as far away as it always has been, and you will get there when you get there.

This Zen-like concept of time and distance, while charming and possibly even wise, made it difficult to do business in the conventional sense. Often the closest we could get to pinning down a gong-gong was for “Friday” or “Tuesday.” We considered ourselves lucky if we could at least specify morning or afternoon.

You might think that the Ghanaians’ laid-back approach to time would make them readily available to start a meeting as soon as we arrived, but no. Often we sat around an hour or more, watching goats have sex, waiting for things to get going. We occupied ourselves playing our usual games with the children. We started responding to their calls of “Obruni!” by pointing at them and saying “O bebeni!” (Oh, black man!), which made them laugh. I learned how to say “I am not a white man; I am a black man” in Twi (“Menye obruni; meye bebeni”), which got them thinking. Whit and I decided to teach them some American rap lingo, so we invented a greeting, recited with the appropriate hip-hop arm gestures:

“Yobruni!”

“ ’Sup, bebeni?” And so on.

In one village, out of boredom, Whit caught a striking red-speckled grasshopper. Knowing the African child’s pastime of putting insects on “leashes” made of strings, Whit gave the bug to a small boy. He dropped it and stomped on it.

Often there would be something culturally edifying to watch, like the Krobo bead makers in Bomase. In the village of Twum, a man named Foster Appia made sturdy rattan market baskets while listening to his Burro-powered radio. One time I saw two men by the side of the road flip a live sheep onto its back, tie its legs together, load it into the trunk of a taxicab, and drive off. I thought that was pretty impressive, but the next day I saw a taxi with two sheep in the trunk. At one gong-gong, the chief, who had been drinking apio, was having trouble getting a sound out of the shell horn he used to start the meeting. Jan offered to try, and the villagers laughed. But Jan had played saxophone in school and was the bugler at her summer camp. They cheered when she belted out a perfect note.

One day Kevin asked if I could go with him to a gong-gong. “I promised this village an obruni,” he said, which always seemed to help drive interest in the batteries. “If you can’t, no problem; I can tell them my white man has traveled.”

“It’s fine, I can be your white man,” I said. But we got there and everyone was too busy: a government-sponsored malaria control program had villagers clearing brush from around their huts.

At a gong-gong in a school in Behanase, a man in an Obama T-shirt who had lost his right leg at the knee in a car accident was complaining to his neighbors that someone was stealing from his farm. “If I catch them I will cut off an arm,” he said. “If a cripple like me can farm, then able-bodied people should be able to do their own farming.”

Another time, Rose and I had a meeting with a chief in a small village called Meawm’ani. A gray-haired man in his sixties who wore a traditional African tunic, the chief seemed like a wise and thoughtful leader. But after examining a battery and listening to Rose’s introduction, he demanded twenty cedis for organizing a gong-gong, a request that bordered on extortion. If he thought Rose would be a pushover, he was very mistaken.

“Twenty cedis!” said Rose. “I have never paid more than five cedis for a gong-gong.”

“Okay, five,” he said, “but you must pay me now.”

“No,” she replied. “I will give you two now, and three later if you make it happen.”

“I want five now,” he insisted, “and I will give you back three if it doesn’t work out.”

Rose shook her head. “You know, where we live there is electricity. We can go home tonight and turn on lights. So we are just trying to help you and your people in this village. Yes, we want to make some money, but we are not making that much.” None at all so far, she might have added. The chief finally agreed.

The process of training agents was arguably even more important than the gong-gongs, because the agents would be on the front line of battery sign-ups every day. The gong-gongs were a key driver of initial interest in the program, but if the agents didn’t get it—and feel inspired to promote it—the whole thing would collapse.

One day we trained three new agents in Amonfro, a village on a main road out of Koforidua, toward the Akwapim Ridge. One of the agents, Enoch, owned a small chemist shop in town; the other two, George and Monica, were shopkeepers in nearby, smaller villages. Whit began the training session by outlining the company’s values:

“The first is respect—for you the agents, and the clients. We follow the Golden Rule of do unto others as you would want them to do unto you. We will always respect you and be honest with you, and we need you agents to show respect for the clients. And we hope you will have respect for us and the company and what we are trying to do.

“Number two is innovate. We are still learning. We are always looking for better ways to do things. We are a team, and we can go farther if we share ideas. So please do not hesitate to tell us when you have an idea for a way we can serve our customers better and help them do more.

“The final value is empower. Burro is about helping people do more. So talk to your customers about doing more. Our offering is very simple: better battery for the half the price. You need to spread the word that people can do more with our batteries.

“We will come to visit you two times a week to change batteries and collect names of new clients and money. Your commission is twenty percent on batteries, ten percent on merchandise like the phone charger. You can take your commission then, or if you like, we can hold it for safekeeping until you want it.* Are there any questions so far?”

“How do we sell the batteries?” asked George, a handsome, thoughtful man whose nearly identical (but not twin) brother was also an agent.

“That’s a very good question,” said Whit. “Let’s talk about selling. When someone comes the first time to get batteries, you need to take a deposit of one cedi for each battery. This is very important because the battery is very expensive. You need to tell the client two very important things. The first thing is that the battery is not for sale. They are borrowing it. The second thing is that they can get back their deposit any time they want if they bring the battery back and do not take fresh.

“Now, the client has to join the program the first time. That’s how you sell batteries. So the first time only, they must fill out the form.”

Whit pulled out a printed form the size of a filing card. “You have on this card client one, client two, and client three. First you get their surname—the name they gave at school. Then you write down any other names, their phone number—”

“Not all have phones,” said Monica, a quiet young woman.

“That’s okay,” said Whit, “but please ask. It will help us to market to them, which will mean more sales for you.” (Cell phone penetration in Ghana reached 75 percent by the end of 2010.)

He went on: “Then you get their birth date or age—if they don’t know how old they are, just make a guess. Check whether they are male or female, on grid or off grid; that means if they have light. You mark the date they started, how many batteries, and if they took them alone or with an adapter. That’s it. You only need to do this the first time they sign up. Any questions?”

George again: “What about the coupons?”

“Another very good question. When they use the batteries and come back for fresh, they have three choices. If they want to pay half the price of Tiger Head, they must buy a coupon book for two cedis.” He held up the book. “With this they get sixteen batteries, or eight pair. And now, for a short-time promotion, they get four extra. So twenty batteries for two cedis.

“They can also buy one battery at a time, for twenty pesewa each. We call this pay as you go. It’s still less than Tiger Head, but not as great a savings.

“Finally, if they can’t afford two cedis but want a better deal than pay as you go, they can buy a one-cedi book, which gives you seven batteries.

“One more thing on the commission: with the coupons, you get ten percent when you sell it and ten percent when the coupon is redeemed. So you should always redeem coupons, even from clients who did not buy them from you. If anyone has a coupon and a fallen battery, they are entitled to get a fresh battery—even if you don’t know them—and you will get ten percent commission on their coupon.

“Now, we would like to set you up with fifty batteries and twenty adapters. You put the fallen batteries in the red tub; we will pick those up and give you fresh. Keep the fresh in the green tub. Please do not mix them up! Are there any more questions?”

None.

“Okay, thank you,” said Whit. “If in four weeks you are still selling any Tiger Heads from your shops, you are doing something wrong.”

He was kidding, because he knew Tiger Heads had one clear advantage. One day we watched a man listen carefully to the Burro pitch in front of a shop, then plunk down one cedi for four Tiger Heads. Whit shrugged. “We are definitely not the cheapest battery today. You can get Tiger Heads cheaper the first time.”

Kevin said, “That man stood there for a long time listening. He wished he could get the Burros, but he needed four and did not have the money for the deposit.”

Batteries were not the only unpredictable technology in the business. Burro’s “Avon lady” model depended on vehicles to deliver fresh batteries to villages along routes that Whit, Jan, and the employees had designed. When the business was new and concentrated along just a few main roads leading out of town, route management was relatively simple. But as business expanded in several directions and Burro started racking up dozens of agents in an ever-widening circle around Koforidua, scheduling the cars became a math puzzle. In particular the route teams competed briskly for use of the Tata, which had four-wheel drive and high clearance and could go where the tiny Kia could not. There was little room for error in the schedule; if someone came back late from a gong-gong or a meeting with a new agent, events for the rest of the day tumbled off the calendar, like a blizzard at O’Hare rippling into flight delays across the country. Complicating matters were Ghana’s punishing roads, which sent both cars into the shop constantly. Flat tires were relatively easy to fix; a major breakdown was inevitable.

One Tuesday morning in August, Whit, Adam, and I were driving the Kia to Mamfe to train two new shopkeepers as Burro agents. It was a key expansion, the closest we had come yet to Accra: one shop was in the busy tro-tro station and another on the town’s main roundabout. Both had the potential to move tons of batteries, but we had almost no experience in urban, electrified markets, where customers would almost certainly be more transient and anonymous. Would they return the batteries?

Suddenly, rounding a tight curve at about fifty miles an hour, the Kia shuddered violently and swerved right. “Hold on, kids,” said Whit as he gripped the wheel and pulled hard left, trying to stay on the road.

“Whoa, that doesn’t feel like a flat,” I said.

“I think it’s a wheel bearing,” said Whit. He drifted to the side of the road and limped another hundred feet to get past the blind curve. Fortunately there was no open gutter along this stretch, but the shoulder was still nonexistent. Overloaded trucks, hauling tomatoes and bananas to Accra, were bearing down on us at high speed, horns blaring and stones flying. We pressed open the doors a crack and escaped into the tall elephant grass along the side of the road. The right front wheel was smoking from the hub. It was starting to rain.

“This business is hard,” said Whit in a mock whine. The metaphor nobody mentioned was obvious: were the wheels also falling off the business? “It was so much easier to sell board games,” he added.

“And as I recall you took the bus to work.”

“I did.”

Whit got Kevin on the phone. “We’re past Adenya junction, near Kwamoso. I’m wondering if we should call a mechanic in Kof-town or get Samuel up from Accra.” (There is virtually no concept of tow trucks in Ghana; most mechanics, few of whom have their own cars, travel with their tools by taxi or tro-tro and make repairs at breakdown sites, working in traffic. Often they have to travel twice—once to assess the nature of the repair, then back to get parts. If you can be sure of the problem in advance, your mechanic can arrive with the right parts the first time.)

Kevin advised calling Samuel, Charlie’s mechanic in Accra, who had in fact checked out this car and recommended it for Burro—not least for the very good reason that it is a common car in Ghana with readily available parts. Whit reached Samuel, explained the situation, and hung up. “He can’t leave Accra until noon, so he’d get up here on the tro-tro around two.” It was now nine-fifteen.

Whit called Kevin again and asked him to contact the Koforidua mechanic we’d used in the past. “Maybe he can get here sooner than this afternoon,” said Whit. We sent Adam back to the office in a tro-tro; no sense in three of us eating dust all morning when Adam could be working on the books. Whit and I walked ahead another hundred yards to a small turnoff—nothing more than a path to a small settlement in the forest—where a woman and her two young children were selling bags of gari under a bamboo shelter. “If we can get the car here, we can pull it off the road and jack it up,” said Whit.

“Well, the bearing’s obviously fried so I don’t think we can hurt it any more,” I said, conveniently ignoring the unpleasant possibility of toasting the entire hub with more driving. “Just take it slow.” We nursed the Kia up to the clearing, backed into a spot next to the gari stand, and hauled out the jack as the gari lady and her children looked on curiously. Kevin called back with news that he could come down in the Tata with the mechanic in an hour or so. “We got the tire off,” said Whit, “and it’s definitely the bearing, maybe also the hub. But I doubt he can pull the bearing without a press, so he should probably bring a whole hub. I’ll leave it up to him, but don’t let him come down here without parts.”

Whit and I hailed a taxi and sped up the ridge to Mamfe for our training session with the two shopkeepers. Obviously, we were late. Fortunately, shopkeepers are usually around their shops. We sat in the usual plastic patio chairs, but this time we weren’t under a mango tree in a village with a gong-gong man. This time we gathered under the awning of the Redeemer shop at the noisy tro-tro station. In case anyone might miss it, the store said REDEEMER REDEEMER REDEEMER across the cornice. Redeemer sold the usual mix of everything, Africa’s version of a New England general store—from aluminum bowls to spaghetti to matches to cans of Malta and penny candy in jars. And batteries—both Tiger Head Ds and Sun Watt AAs.

The owner, Emmanuel, was a gray-haired man in a bright red traditional African robe with fancy black piping that is typically worn for funerals. He greeted us with the usual Ghanaian smile and warmth—“You are welcome,” he said—and went off to get his wife, Janet Twumasi.

It soon transpired that Janet was the real boss, for as soon as we sat down she announced she was no longer interested in selling our batteries. “It’s too complicated,” she said. This was not a total surprise, as she had relayed as much to Kevin a few days earlier. He had talked her back into the program, and as far as we knew she was on board. But now she was waffling again. Whit whipped out his phone and dialed Kevin, then put her on. Several minutes of Twi later, she was back in the program, but I didn’t sense much enthusiasm. It seemed clear that the conventional Burro training process—starting with the inspiring rundown of the company’s values and commitments to empowering Africans—would fall flat here.

“You better cut to the chase,” I murmured to Whit.

“No kidding.”

We were joined by Christy, the daughter of the shopkeeper a hundred yards away in the roundabout. Christy seemed more plugged in to the concept. “If someone comes in to buy Tiger Head, I will tell them that Burro is a better deal,” she said.

No such insight from Janet, who seemed mystified by the whole coupon-book thing. She was, however, laser-focused on the twenty-pesewa individual purchase offer—even though that cost customers more money and earned her less commission. Undoubtedly she was planning to push individual recharges, and not even tell customers about the “complicated” money-saving coupons.

We walked over to Christy’s father’s shop, where she worked behind a five-foot-long glass display case that contained nothing but packaged cookies—I counted a dozen varieties of chocolate chips, ginger snaps, and others. I’m no expert in merchandising, but it seemed an odd use of prime retail frontage considering the cornucopia of wares on offer in the shop—especially as each cookie brand was piled several packages across. Assuming it was essential that her customers see every brand of cookie available, wouldn’t it suffice to display one example of each? I caught Whit’s eye and nodded toward the display case. He politely suggested to Christy that she might consolidate the cookies and make a little room for a stack of Burro batteries. She nodded in agreement. Whit and I looked at each other as if to say, “No time like the present!” But that’s not how time works in Ghana. Several days later, there were still no batteries on display—only cookies—and this was a merchant who seemed excited about Burro.

Whit and I clambered into a packed, sweaty tro-tro for the forty-minute ride back to Kof-town. “So you’re back on the bus after all, Whit,” I said. He ignored me and turned to the New York Times on his smart phone, looking up only to glance at our sad, broken-down Kia as we flew past it, still jacked up in the clearing by the gari stand.

A few days later, Kevin reported that both Mamfe shopkeepers were still pushing back on the process of taking down clients’ cell phone numbers and other information. “Christy says many people do not want to fill it out,” he said. “Also the people at Redeemer say it is too much trouble.”

“Okay, then let’s close them down,” replied Whit.

“So we lose that money?” asked Kevin.

“Yes, if they won’t do it our way. Look, I hear you—maybe long-term we do it some other way, but I’m just not ready to give that up yet, for several reasons. Fraud is one, also marketing and brand building. The sign-up makes it clearer that the customer is entering a program, not just buying a Tiger Head. That’s really important. I mean, I think we have a really compelling offer here, and frankly I don’t want to do what Cranium did with Walmart, which is when they say ‘Bend over,’ we say ‘How far?’ So you should tell agents that gathering this information will help us to market to their clients, which will earn them more money. And another way to put it is that people are giving us one cedi for a battery that’s worth like six or eight cedis. So we are essentially loaning the client several cedis. Ask them, would they give away five cedis to a complete stranger without getting some information from them?”

“But if someone wanted to steal,” said Kevin, “he could just give a false name and phone number.” Kevin was beginning to sound like Charlie.

“Right, but most people won’t,” said Whit. “There may well be some theft, but we don’t want to make it easy for them. And I think some people will just forget, or lose batteries, and this gives us a way to track them. Again, Kevin, I hear you on this. But we need to test it. If we never test it in a big urban market, we’ll never know if it works or not. We need leadership from you guys in the field on this. You can’t seem to be waffling and say, ‘I’ll go to the obrunis and see what they say.’ You need to be in charge and explain it.”

“Oh no no no,” said Kevin. “I will explain it to them.”

“Okay, good,” said Whit. “Keep in mind that when we get smart cards, which is the holy grail, it’s not gonna be any easier, because agents are still gonna have to fill out the card when they sign a new client so we track their usage and make offerings. So this information is a huge advantage to us and the agents, and you have to make that clear to them.”

Most of Burro’s business was still in small villages around Koforidua, where personal relationships with agents and clients made a huge difference. So even while expanding to the big city, we were talking about seeding goodwill in villages—the process of greeting chiefs, queen mothers, and youth leaders and giving them free battery coupons (they still needed to sign up and pay their battery deposit) in order to spread the word. “That’s a very good thing to do,” said Adam, whose late father was an Ewe subchief in the Volta community of Adaklu, actually a collection of thirty-nine villages around a sacred mountain of the same name. “The chiefs can be very helpful to us.”

Or not. One day we trained a shopkeeper in the largely Ewe village of Mintakrom, where the chief had seemed cool to us. After sitting through a one-hour training session, the man stood up and spoke to Adam in Ewe. “He says the commission is not enough for him.”

“Okay, I respect that,” said Whit. “We’ll find another shop owner.”

“He says they will all say the same thing.”

“Do you interpret that to mean they’ve been told to say that?”

“Yes.”

We drove on. “Adam, what about the whole schnapps thing?” Whit asked. The traditional gift to a chief is a bottle of Dutch schnapps, which costs anywhere from five to ten cedis, depending on quality—and the chiefs know the difference. “We’ve been burning through cases of schnapps, and I’m not sure it’s really necessary.”

“If you are just stopping by to meet a chief, then I would say no,” said Adam. “That’s more for a formal meeting with the chiefs and the elders.”

“They won’t be offended if we don’t always bring schnapps?”

“Oh no.”

“That’s good, because I see huge value in this approach Jan has been using of just pulling off the road, finding a group of people, and building enthusiasm. That creates a very different dynamic than showing up and immediately going to the chief. All of a sudden it’s very proscribed—you know, the chief says, ‘This guy will work with you, he will show you around.’ We don’t get to tell our story and pick who we would pick to be the agent. We get stuck with the chief’s son or something. So we need to balance the formal approach and the gong-gongs with the guerrilla tactic. And yeah, I can see where we should then go greet the chief and say hello—you know, ‘If you have time next week we’d love to sit down with you and the elders and explain the program.’”

When the routes started overlapping, banter between the teams grew more pointed. Jan and Rose came back one evening with the news that they’d secured a potential agent in the key junction town of Nkurakan. “You know, the guy in the polio shirt,” Jan said.

“Polo shirt?” said Whit.

“No, polio shirt, like Hayford wears—the polio eradication Rotary Club shirt. Well, actually it is a polo shirt, so a polo polio shirt. Anyway, he was great, showed us all around town, actually made us late for a meeting.”

“Wait a minute,” said Whit. “This is gonna cause problems because Nkurakan is a nexus for both our routes, and Kevin and I already had our sights on Yoko Ono in that town. She has the best shop.”

“There’s a woman named Yoko Ono in Nkurakan?” I asked.

“Yes. We drive through Nkurakan twice a week,” said Jan.

“So do we,” said Whit.

“Well, Kevin already said it was okay.”

“Look, Jan, keep your mitts off our turf in Nkurakan.”

I never settled the issue of the woman named Yoko Ono. The guy with the polo polio shirt turned out to be a dud.

Out in the rural villages, we started ramping up the guerrilla forays—touching down in a new location and identifying our agents and shops first, while still being careful to pay respects to the leaders and schedule gong-gongs, which usually led to lots of new sign-ups.

One day Jan, Rose, and I headed north from Huhunya, following a dirt road that runs past Boti Falls, a one-hundred-foot cascade and one of the country’s major scenic attractions. Joining me in the backseat of the Kia was our newest agent, a smart young man I’ll call Nkansah, who plied these roads weekly (on foot and by bush taxi) as a “medicine man,” delivering drugs to villagers.

“What kind of drugs do you deliver?” I asked Nkansah as we bounced along.

“Mostly painkillers,” he said. “Farmers hurt their backs a lot. Also Chinese herbal medicines for hypertension. You drink it in tea. I bring a machine to measure blood pressure.”

“That’s really a problem here?” I asked, wondering how people who did so much hard physical labor could be hypertense.

“It’s a very big problem in Ghana,” he said. “Too much palm oil in the diet. There is also a lot of diabetes.”

Nkansah’s genuine concern for the health of these villagers belied his long-term goal in life, which was apparently to become the Sammy Glick of Ghana. He was diligently saving his money, he said, so that he could afford tuition for business school in Accra. He wanted to study marketing. Already he was combining his health-care expertise with business acumen: “My uncle and I have brought some moringa cuttings from Tamale, and we are raising our own crop to sell for diabetes patients.” (Studies have shown that the leaves of the moringa, the so-called miracle tree, which Jonas had told me cured ninety-nine ailments, can help control glucose levels.)

We turned left at the Don’t Mind Your Wife Drinking and Chop Bar,* then headed deep into the bush on a bad road to the twin villages of Opesika and Sutri (the first was an Akwapim tribal stronghold, the second Krobo). Jan was getting concerned that these villages were too far off the route track, too difficult to service, but Nkansah insisted: “I will come every Thursday and the people will be ready then. There is a lot of opportunity here.” Jan relented, and we drove on to the villages, which turned out to be unusually pristine. Almost every house looked freshly plastered and painted, as was the shared school. A small health clinic seemed well stocked and was staffed by two workers. The children spoke excellent English—sign of a good (meaning well-paid) teacher. Opesika and Sutri felt like Hollywood movie versions of African villages.

We got out of the car, and Nkansah immediately started moving from door to door and shop to shop, showing batteries and launching into his spiel. Just about every person got it immediately and promptly whipped out cash for several batteries—lots of cash. Typically, when poor villagers make the important lifestyle decision to sign up for Burro, they carefully unwrap their savings from a handkerchief or skirt tie—a few filthy cedi notes and pocket change. But these people were flashing the Ghanaian version of a Philadelphia bankroll. Just about every customer paid with a crisp, new ten-cedi note, quickly draining our cash box of change. When one guy pulled out a twenty (the first I had ever seen in Ghana outside of a bank), I shot Jan a look; she raised her eyebrows. On the drive back, Jan asked Nkansah where these villagers got all their money.

“Oh, they have secret farms,” he replied.

“Secret farms?”

“Indian hemp. Marijuana. They grow marijuana.” Nkansah said this as if the crop in question were rutabagas, or pomegranates—a curious specialty item in the grocery store perhaps, but nothing out of the normal agricultural sphere. This was surprising because Ghana is not some stoner’s paradise; Bob Marley may be the most popular musician in the country, but his drug of choice is strictly illegal here—possession can bring a sentence of ten years’ hard labor—and not at all common outside a few Rastafarian enclaves in beach communities frequented by student travelers. “A farmer can sell a sack of Indian hemp for one hundred fifty Ghana cedis,” Nkansah the entrepreneur added. “Very good business.”

“Indeed,” said Jan, no doubt mentally comparing hemp profits to Burro’s languid balance sheet. “Do they hide it in between their regular crops?”

“Oh no, they just plant the whole field with it,” he said. “When the police come, the farmers pay them.”

Coincidentally, the very next day Whit saw an article in one of the papers headlined POLICE WILL “NOT RUSH” IN YILO KROBO NARCOTIC CASE. Yilo Krobo was the district we had been driving through the day before. “The Police Administration says it would ‘not rush’ to prosecute police officers alleged to have been taking bribes from Indian hemp farmers at Yilo Krobo,” the article began. Officials said they would instead follow due process and conduct an orderly investigation, after some politicians complained that police bribery had encouraged more farmers in the region to take up hemp farming. Given that the crop has brought obvious prosperity to Krobo communities and (to my observation) no local drug problem whatsoever, it seemed likely that any political pressure to “clean up” the district was window dressing.

If only every new village were as flush as the secret farmers. After a one-hour gong-gong in Twum, a village on the other side of the route, with no secret farms, the large crowd fell silent. “I guess what I want to know,” said Whit, “is why would anyone still use Tiger Head?”

A few people finally straggled up, mostly out of curiosity. Others admitted they simply had no money at the time. And for others, the issue of timing loomed large: someone who has just bought a new set of Tiger Heads needs to wait until those run down before buying Burro replacements. As we drove off in the dusk, lunking down a warped dirt road, Whit reflected: “It’s increasingly apparent that this business is brain-dead stupid simple and really hard at the same time.” It was getting dark fast, we’d never had lunch, and we were looking at nearly an hour’s drive home. It was a road we knew as well as one another, but you can never get to know the potholes because they change daily, so we stayed vigilant, trying to avoid fatal complacency. “But we’re gonna change this country,” said Whit, banging the steering wheel. “We’re gonna change this country one battery at a time.” That was when I began to see Whit as the gong-gong man.

Lunch on the road was usually the most basic street food: salty boiled peanuts ( just like the kind you get in the American South), grilled plantains, an ear of grilled corn, sometimes a hard-boiled egg with homemade hot sauce (tomatoes, rock salt, onions, and searing Scotch bonnet chilies, pulverized with a mortar and pestle), all of it washed down with purified water in five-hundred-milliliter plastic “sachets.” But this simple repast was rarely enough for Kevin, whose knowledge of Ghanaian cuisine was encyclopedic and in constant need of fact-checking. He ate perpetually and with abandon. Entire dried mackerel, heads and all, disappeared into his mouth like a sea lion. I too enjoyed the ubiquitous dried fish of Ghana (in a country with very little refrigeration, every size and species of marine life, from minnows to tuna to shrimp and clams, is preserved by smoking or salting), but eventually swore off it on sanitary grounds; it was simply impossible to know how it had been handled. Whit simply hated everything about it. For him, the very smell of dried fish—and it was pungent—filled him with inchoate revulsion, although we both liked the fresh tilapia from Lake Volta.

Not everything Kevin ate agreed with me. He exhibited a passion for deep-fried chunks of cocoyam that to my palate tasted (and to my eyes looked) like Ivory soap. And he reserved his greatest ardor for fufu, the gooey Ghanaian staple that Whit and I both agreed was not so much awful as forgettable. Kevin could go only so many days without tucking into a massive sticky ball of fufu, and I’m not counting his dinner, which for all I knew included fufu every evening. One day, scouting new territory up on the ridge with Whit, the fufu jones got ahold of him.

“Kevin browbeat me into fufu for lunch today,” said Whit that night over dinner at the Capital View Hotel. “I told him, ‘Dude, I’ll be honest with you. I’ve got a real problem eating with my hands.’”

“You’re eating with your hands right now,” I pointed out.

Whit dropped a French fry on his plate and glared at me.

“I told Kevin I’d eat fufu if I could use a knife and fork, but if that was gonna cause an international incident, we better forget it. He said fine. So we get to this place and there’s like two choices: fufu with brown goat soup and fufu with brown fish soup. The goat looked like pieces of gristle. The fish soup at least had recognizable cross-sections of fish, but there were also lots of heads and fins floating around in there. You had a choice of one or two pieces of meat. I ordered the fish with two pieces, figuring the chances were fifty-fifty that I’d get some meat and not just heads.”

“Maybe you could flip a coin and get heads or tails.”

“I think the tails are for garnish. Anyway, Kevin got the goat. I couldn’t tell what the hell those pieces were. It was like goat kneecaps or fetuses or something. Of course he wolfed it down. I think he ate the bones.”

Yet even Kevin had his limits, his culinary no-go zones. One day, in the village of Nyame Bekyere (which means “God will provide” in Twi, and is the name of possibly six dozen villages in Ghana), Whit was meeting our agent, Nana Bekoe, while Kevin and I waited in the car. Nana, an Ewe, ran a local drinking spot whose walls were plastered in posters of Flight Lieutenant Jerry Rawlings, the former military coup leader. Like his political hero, Nana was a man of status, albeit in a very small village—a distinction that in his mind excused him from a life of drudgery and toil. He spent most of his time engaged in heated games of checkers under a palm-frond canopy next to his drinking spot, surrounded by his acolytes and multiple litters of mangy, featherweight cats. When it became apparent that being a Burro agent meant distracting interruptions of actual work, Nana recruited a gang of older boys and young men to be his battery runners. The details of this business arrangement remained obscure to Whit, but he assumed Nana collected a hefty percentage as the godfather of this makeshift syndicate.

After a few minutes, Whit returned to the car and said, “That was weird. I was petting one of Nana’s kittens and he said, ‘When they get bigger I will give you one.’ I said ‘Yeah, just what I need is a cat.’ And he said ‘Don’t you eat cat?’”

Whit turned to Kevin, who was driving. “He was kidding, right?”

“Oh no,” said Kevin. “The Ewe, they eat cats.”

“Oh come on,” said Whit. “You’re not serious!”

“Yes, they do. They call it Joseph.”

“Joseph? You mean, like pig is pork, cow is beef, cat is Joseph?”

“Yes.”

“I don’t believe you. I’m calling Charlie.”

“He will confirm it.”

Whit picked up his phone. “Good afternoon, Charlie. I’m calling you with a quick question. Kevin says that the Ewe eat cats, and they call it Joseph. Is it true?”

There was a brief pause.

“Really! Do you eat it yourself? Okay, thanks, Charlie.”

He hung up. “Charlie says it’s true. He said, ‘Don’t ever leave your cat with an Ewe.’”

“I told you it was so,” says Kevin.

Back in the office, I decided to confirm this revelation with a second Ewe source. “Adam, do you eat cat?”

The young accountant looked up from his laptop. “Yes.”

“Joseph, right?”

“Yes. It’s very nice.”

“Nice? Yes, most people would agree that cats are nice. Why is it called Joseph?”

“I don’t know why,” he replied, pondering the question as if for the first time.

“How do you prepare it?”

“Oh, in a stew,” he said with a tone of surprise at the inanity of the query. Everything in Ghana is prepared in a stew.

“What does it taste like?”

He thought for a minute. “I don’t know how to describe it.”

“Like chicken?”

“No, it doesn’t taste like chicken. More like rabbit. Do you eat rabbit?”

“Indeed,” I replied, which made me wonder why we find it so repulsive to eat certain pets (assuming one eats any kind of meat at all). The Ewe also keep cats as pets, but they are somehow able to compartmentalize Tabby while dining on Joseph. But they regard the consumption of dog as absolutely barbaric. I posted the whole Ewe cat food thing on Facebook and got a lot of responses. My friend Steve Vickery suggested serving cat topped with dried cat food, “for extra crunch.” Don Rainville wondered why we abhor eating pets since we have no problem eating vegetables, even though we keep house plants. It’s a good question, but I decided I would politely turn down offerings of Joseph, unless doing so would cause grave offense to a village chief.

The first counterfeit coupons showed up on 9/11. To a casual observer they were not obviously fake, but Jan was no casual observer. It was Friday, the end of a hectic week and her last day in the office before a three-month trip home. Over the summer, while Jan worked in Ghana, she and her partner Leslie had bought a house in Medford, Oregon—four hundred miles from her previous home in Seattle—where Leslie had taken a job as pharmacy manager for a local hospital. Between packing for her trip and looking forward to seeing her new home, Jan could easily have been distracted enough to miss the eight fake coupons in the cash box from that day’s route. But she thought they looked funny, so she looked again. They were the right size—one and a half by two and three quarter inches—with the right words (“ONE BURRO EXCHANGE, FRESH BATTERIES ANYTIME”), but the font looked just a little too small. And the image of the Burro battery with the donkey logo was grainy. What’s more, the fakes had a dotted-line border around the edge, like a cutting guide, which the real coupons did not. Also there was no staple mark; these coupons had never been part of a booklet. Obviously someone had made a copy of an original coupon, then copied it several times more, compromising the resolution just enough to be noticeable if you took the time to compare. “Hey, Whit, look at this,” Jan said.

“Holy shit,” he replied, staring at the bogus slips, holding them up to the light. “Wow. That didn’t take long.”

“Definitely from Bomase,” said Jan. “It’s the only place we collected at least eight tickets today. And they came from either Seth or Dorothy,” two Burro agents there who had redeemed a bunch of coupons. Seth was a smooth-talking farmer with a cool straw hat whom we had met on that very first day in Bomase; Dorothy was the wife of a former assemblyman and the town’s youth leader. Both were high-performing agents and among the first under the new system.

“Do you think Seth or Dorothy know?” I asked.

“I don’t know, but I doubt it,” said Whit. “Most likely one of their clients, without their knowledge.”

“Just one?” I said. “Don’t kid yourself. Those Krobos have been copying Venetian glass beads since the fifteenth century. Even the Arab traders couldn’t tell them apart. Have you ever looked at some of the patterns on those things? Faking up some Burro coupons would be child’s play to them. You’re in deep shit. And did I mention they also grow dope?”

“This is nuts,” Whit said. “As if this business weren’t hard enough.” He slumped in a chair and opened a beer. “Today I drove for ten hours, covered a hundred and eighty kilometers, and came home with forty cedis and some counterfeit coupons. Totally nuts. We need a lot more volume.”

We were all feeling a bit violated by this breach of faith. Charlie always said, “You try to help poor people in this country, they just take advantage of you.” Whit and I had always hoped he was just being overly fatalistic, but maybe he was right. Maybe you couldn’t help poor people. Obviously bad guys were out there watching us, looking for ways to game us. Fix this leak and they’ll spring another one, somewhere else in the system. Do More, indeed. They were mocking us!

“What are you gonna do?” I asked Whit.

“Nothing yet. Wait and see. Let’s monitor the situation, see who’s turning them in. I don’t even want to tell the agents yet. When we find out who it is, maybe we pay them a visit with the assemblyman and the police. We may need to do a currency call-in—you know, exchange your old coupons for new ones, and after thirty days we won’t honor any coupons without the new stamp. Shit, I don’t know. This business is hard.”