In this temple dwells Jupiter: let its ruler convince you that it is to be reverenced.

Manilius, (c. 10 AD) Astronomica, II v.893

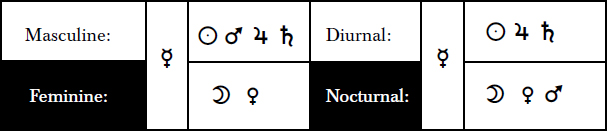

Although all houses derive some of their meaning from the Sun’s relationship to the earth, not all of them are as clearly dependent upon it as those discussed so far. Obviously other factors are involved and in searching for the origin of meanings it soon becomes apparent that there is no one single philosophy that can be used to completely illuminate the evolution of their significations. Our current house meanings are the product of amalgamated symbolic viewpoints whose integration has settled over many centuries. Significations attached to spatial sections are to some extent borne from diurnal revolution, but aspects have also played a part, as have inter-house relationships and proximity to the cardinal points. Another dominating influence was what we have now come to know as the planetary ‘joys’ or areas where the planets ‘rejoice’. These have been fleetingly mentioned so far and are illustrated in the diagram showing the rulerships of Firmicus, who referred to the eleventh house as ‘the house of Jupiter’ with the same sense of natural affiliation as when he refers to Sagittarius or Pisces as ‘the sign of Jupiter’. To classical astrologers the relationship between a house and its planetary ruler was very considerable. In modern astrology the associations have become all but forgotten.

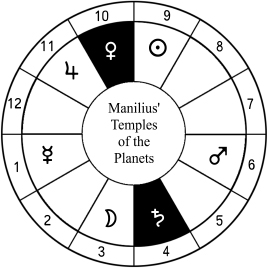

The use of planetary ‘house rulers’ is paramount in the work of Manilius, who referred to the houses as the temples of the planets. His scheme is notable (and often dismissed) however, because he differs from other authorities in attributing Venus to the 10th house and Saturn to the 4th. All later authors of the sources we have extant consider Venus to take residence in the 5th house and Saturn in the 12th. But this point could be of substantial importance, since it can be seen that an alteration in house meanings also occurred with the alteration of the planetary rulers. Consider first the description that Manilius offers of the 10th house, considered by him to be ‘the temple of Venus’:

“To this abode is fittingly given the power to govern wedlock, the bridal chamber, and the marriage torch; and this charge suits Venus, the charge of plying her own weapons. Fortune shall be this temple’s name; mark it well.”1

Manilius was not unique among the early astrologers in attributing marriage to the 10th house; other authors, including Ptolemy, followed him in that. But it is interesting to note how his understanding of this ‘abode’ ties in with the natural signification of the planet he associates it with. By contrast, his description of the 5th house is very brief and bears little resemblance to the interpretations of later authors who were to recognise it as the house of Venus. Speaking first of the 11th house, Manilius continues to describe its polar opposite:

“Like this temple [the 11th house], but with an inverse likeness, is that which is thrust below the world and joins the nadir of the heavens [the 5th house]. Wearied after completion of active service [as it passed through the 6th] it is again marked out for a further term of toil, as it waits to shoulder the yoke of the cardinal temple and its role of power [as it moves towards the 4th]: not as yet does it feel the weight of the world, but already aspires to that honour.”2

Some astrological historians suggest that Manilius’ variance on the association between houses and planets should be dismissed as an error, but deeper scrutiny of his text reveals the connection between a planet and its ‘temple’ to be much more emphasised and influential in his interpretations than we find in later works. More likely, the associations he described were very much in line with the scheme he was presenting, and they certainly seem central to the meanings he attributed to the houses. The evidence for this is also striking in the case of the 4th house, which Manilius described as the temple of Saturn:

“Where at the opposite pole [from the MC], occupying the foundations, and from the depths where midnight gloom gazes up at the back of the Earth, in that region Saturn exercises the powers that are his own: cast down himself in ages past from empire in the skies and the throne of heaven, he wields as a father power over the fortunes of fathers and the plight of the old.”3

Here the natural association between Saturn and the traditional rulerships of the 4th house appear too convincing to be brushed aside as a mistake. The 17th century astrologer William Lilly, for example, linked patrimony (ancestral wealth) with both Saturn and the 4th house; the same is true of agriculture, the aged, fathers, the earth, toil, mining, minerals, drowning, death, burial and tombs. In fact, almost everything traditionally linked with the 4th house is also naturally associated with Saturn.

Rather than concluding that Manilius’s astrology is flawed in its presentation, it seems much more reasonable to assume that this was part of the design. Manilius is the oldest source to which any house interpretations can be traced, so he perhaps portrays an earlier cultural viewpoint, one that was subsequently adapted to modify the way the houses and planets were linked together. Manilius states that he is introducing to the classical world “strange lore untold by any before” and his many references to oriental gods and myths suggests that he was more directly in touch with the philosophies of the older civilisations than the later classical authors whose works were to become the influential sources for western traditional astrology. In addition, the classical culture brought a move towards rationalisation and the impulse to emphasise the logic and science in astrology at the expense of the mystical. Philosophers of the classical period were concerned with neat, balanced and philosophically pleasing schemes, particularly in the case of aligning planets to sects, an issue which sets the astrology in Ptolemy’s Tetrabiblos apart from the more ancient texts of star lore.

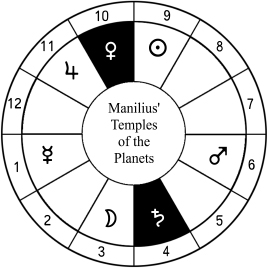

When Ptolemy classified the planets within their sects he defined them as either masculine or feminine, and either diurnal (of the day) or nocturnal (of the night). For the most part these terms, derived from Pythagorean philosophy, are synonymous: the day, characterised by light, heat, activity and force, is generally considered masculine; night, characterised by dark, cold, passivity and rest, is generally considered feminine.

But there is a variation in the particulars: the division of masculinity/femininity is primarily dependent upon the qualities of dryness (masc.) or moisture (fem.), whilst the division of diurnal/ nocturnal is more dependent upon the qualities of heat (diurnal) or cold (nocturnal).

Mercury is dual-natured; both masculine and feminine it is equally suited to the diurnal or nocturnal hemisphere, though appears particularly well placed in the ascendant, where night and day intersect. It was associated with the 1st house, to which ancient astrologers also gave rulership of the intellect. William Lilly notes that Mercury rejoices in this house:

“because it represents the head and the tongue, fancy and memory; when he is well-dignified and posited in this house, he produceth good orators.”4

Of the planets, the masculine planets, Jupiter, Saturn and the Sun, are considered diurnal; the feminine planets, Venus and the Moon, are nocturnal. Mercury, which is dual-natured, belongs to both sects, having an asexual nature that is responsive to its location in the sphere and its aspects with other planets.

We might naturally assume that Mars, a hot planet, is administered to the diurnal sect; and that Saturn, a cold planet, is nocturnal. However, this is not the case. Ptolemy argues that these two destructive planets should be assigned to sects opposite their own natures in order to temper their malefic influence because:

“When stars of the same kind are joined to those of the good temperament their beneficial influence is increased, but if dissimilar stars are associated with destructive ones the greatest part of their injurious power is broken.”5

This does not mean that Mars is strengthened in a nocturnal location; it means that its excess of heat is subdued and moderated, so that its power to destroy is lessened. The same is true of Saturn. These two planets are extreme and intemperate which is why they are considered naturally malefic. They become less likely to damage if Mars (excessive in heat) is located in a cooling environment and Saturn (excessive in cold) is located in a warming one. Therefore all the planets attributed to the diurnal sect (Sun, Jupiter and Saturn) express their energies more favourably in the diurnal hemisphere, whereas the nocturnal planets (the Moon, Venus and Mars) are more favourable in the nocturnal hemisphere.

The definition of planets according to the diurnal or nocturnal sect is based upon familiarity with the Sun and Moon, and the importance of sect in traditional astrological techniques can hardly be overstated. Part of the astrologer’s task was to evaluate the strength and dignity of each planet before any kind of judgement was made, and the affinity of the planets with their own sects was one way to do this. The 13th century Italian astrologer Guido Bonatus includes the following in his list of considerations for astrologers:

“The 47th [consideration] is to consider whether the Significator be in his light or no, that is, a diurnal planet in the day, above the earth, and in the night under the earth, and a nocturnal planet in the night above the earth and in the day under it: for this renders such planet more strong. But if a nocturnal planet be Significator of anything in the day above the earth, or a diurnal planet in the night, the same is thereby weakened and under a kind of impediment, that he can scarce accomplish what he signifies.”6

William Lilly termed the correspondence of a diurnal planet in a day chart, above the earth and in a masculine sign ‘hayz’, but he thought it more appropriate to find a nocturnal planet in the night in a feminine sign and under the earth. In horary questions the significator so found shows “the content of the querent”.7

Reading through the interpretations of planets in the houses given by the 4th century astrologer Firmicus Maternus, it is clear that he lays great stress upon whether or not a planet corresponds with its own sect, with diurnal planets suffering a measure of affliction in nocturnal charts (and vice versa). This example of his interpretation of Saturn in the 10th house illustrates the difference affected by a planet being in or out of sect:

“20. Emperors, generals, and praetorian prefects are the indication of Saturn in the tenth house, that is the MC. If Saturn is on the MC by day and in his exaltation with the Sun on the ascendant, this will make respectable farmers of good character, but wealthy, whose holdings are near the sea, rivers, or lakes. It will also provide large income, great glory, and inheritance from important persons, especially if Mars is not in aspect. But if Mars in strongly aspected he will diminish this good fortune.

21. Saturn by night on the MC indicates misfortunes; loss of inheritance, no marriage, no children, especially if he is in the house or terms of a malefic planet. But if a benefic planet, that is, Venus or Jupiter, is in favourable aspect to Saturn thus located by night, those things which were denied will be given in another way. But in general, Saturn by night on any angle indicates the greatest evils. He destroys wives and children and always predicts grief from loss of relatives.”8

With these examples in mind, it can be presumed that once classical astrology adopted sect as a dominating influence, it would have been considered highly inappropriate for Venus – a nocturnal, feminine planet – to hold dominion over the pinnacle of the diurnal hemisphere; and equally inappropriate for Saturn – a masculine, diurnal planet – to govern the lower nocturnal angle. By re-assigning the ‘temples’ of these two planets from those described by Manilius, the whole scheme falls neatly into place: the diurnal planets reign in the diurnal hemisphere while the nocturnal planets reign below.

Naturally, it would be important to place a beneficial planet such as Venus in a suitably favourable house; and although all the houses below the horizon are considered secondary to those above, the 5th is the most fitting because of its harmonious trine to the ascendant. Similarly, although Saturn shares less of a natural association with the 12th house than it does with the 4th, they have familiarity because both are considered baleful and their influence is limiting and restrictive.

The preceding discussion shows that, in the case of the 5th house, we have an interesting example of how planets associated through the concept of house rulership or ‘joy’ have reflected their meanings into the houses, and how those meanings have modified in accordance with alteration of the planetary associations. Even if we accept that much of the 5th house’s fortunate reputation is derived from the trine aspect to the ascendant, the specifics of the meanings used by authors after Manilius are clearly Venusian in origin. Firmicus is quite clear in informing us that classical astrologers called the 5th house the ‘House of Good Fortune’ because it is the house of Venus. Consider some of its traditional associations: –

• The principle rulership of the 5th house is in signifying pregnancy and children, as befits Venus, the ‘goddess of fertility’ of whom the classical historian Pliny wrote:

“… its influence is the cause of the birth of all things upon earth; at both its risings it scatters a genital dew with which it not only fills the conceptive organs of the Earth but also stimulates those of all animals.”9

• The 11th century Arabic astrologer, Al Biruni, called it the house of joy, clothes, pleasure and friends – all of which fall naturally under the rulership of Venus.10

• The 12th century Hebrew astrologer, Ibn Ezra, describes an association with pleasure, food, drink, gifts and diplomats.11

• The 16th century astrologer, Claude Dariot, used the 5th house for signification of love, ambassadors and gifts.12

• The 17th century astrologer William Lilly called it “the house of Pleasure” and associated it with taverns, plays, recreation and sport – all of which he also ascribed to the natural signification of Venus (including sport as a pleasurable, recreational activity).13

In every instance the derivation from Venus is striking. Modern astrology books that suggest the 5th house is the house of pregnancy and ‘creativity’ because it relates to the 5th sign, Leo, disregard the fact that Leo is marked throughout tradition as a sterile and barren sign – in matters of pregnancy one of the main arguments to judge a denial of fertility. A little reflection upon historical literature shows that few, if any, of the principal rulerships associated with the 5th house derive from Leo; the house has been indelibly tinged with the aura of Venus. It is significant that Manilius did not mention any of these rulerships in his description of the house. He did not place Venus there so had no reason to do so.

The opposite house to the 5th, the 11th, was known to the classical authors as the ‘House of Good Spirit’. A planet appearing in the 11th house has distanced itself far enough from the ascendant to be seen in clear vision, and in the rising of the Sun will be free of combustion. Symbolically, it is perceived to have freed itself of the connotations of captivity and invisibility associated with the 12th house and to have moved into a condition of strength, freedom, release, hope, triumph, movement towards the attainment of desires and general good fortune. Naturally, this is the temple of Jupiter.

Today we call the 11th house the house of friends but that also implies benefactors and anyone who helps and supports our aims, as befits its planetary ruler. All of the symbolism underpinning the interpretation of this house is favourable. Besides its affiliation with the ‘greater benefic’, it forms a sextile relationship with the ascendant and, most importantly, enjoys an elevated position above the earth, rising in diurnal motion towards the summit of heaven. It is this movement upwards towards the midheaven which gives the house a connection with motivation and positive ambition. Manilius tells us that the 11th house is the most fortunate house of all, better even than the 10th; for whilst the midheaven represents completion and power, it has nowhere to aspire to – the only movement it can make is to decline:

“Consummation attends the topmost abode, and no movement save for the worse can it make, nor is aught left for it to aspire to.”14

Not so the 11th house, this “surges ever higher being ambitious for the prize”. Hence it is associated with hope, trust, and expectation – the working towards something whilst the goal is still ahead to garner inspiration. It bestows optimism, joy, faith and luck. Lilly knew it as the house of friendship, hope, trust, confidence and praise, and noted that if anyone asks if they will obtain the thing they hope for, or has a secret wish and is reluctant to tell you what it is, the condition of the 11th house ruler will reveal whether or not they will attain what they want.15 A favourable 11th house and a strong 11th house ruler is a blessing in any chart.