CHAPTER 1

“The Drug Arsenal of the Civilized World”

WWII and the Origins of US-Led International Drug Control

World War II was waged in part as a war for control over commodity flows. As one contemporary expert in economic warfare observed, “in a total war practically every commodity entering into foreign trade is important, directly or indirectly, to the war effort.”1 Even before the United States officially entered World War II, the president authorized economic measures such as export and shipping controls, the freezing of foreign assets, blacklisting, and foreign aid programs to strengthen the Allied cause and weaken the Axis capacity to wage war. Some of the commodities targeted for control were deemed vital to war making; for instance, rubber was needed to make bombers, tanks, and gas masks, and tin was used to manufacture everything from circuit boards to the millions of cans provisioning food for Allied troops. The strategic value of other commodities, including items as diverse as beef, coffee, and cacao, lay primarily in the indirect calculus that US purchasing and stockpiling of such goods could offset war-caused trade disruptions that had the potential to generate economic and political instability, especially for Latin American raw materials export-oriented economies cut off from the transatlantic trade.2

In this context US officials wrestled to control the international circulation of one uniquely valuable group of commodities: pharmaceuticals. The US approach to drug control over the course of World War II constituted a defining moment in the longer history of US efforts to influence the international pharmaceutical trade, to pave the way for US corporate power, and to establish the nation as a formidable political player on the world stage. While World War II was far more than a conflict over commodity flows, the institutionalization of economic warfare policies in relation to the drug trade provide a revealing, if understudied, account of the convergent rise of American power, the war-making capacity of the state, and the economic and political foundations of the US-led “war on drugs” that remains a central feature of US foreign and domestic policy.

The modern history of international drug control dates back to the first decades of the twentieth century, when representatives of European and American colonial powers sought to establish regulatory mechanisms to monitor and channel the international drug trade in directions they deemed essential to their economic, social, and political security. The United States helped spearhead the effort, perpetually contentious, that led to the first international drug control convention in 1912. The International Opium Convention was merely the first in a long line of international agreements (some more widely adhered to than others), and it marked the beginning of what would become a century-long saga driven by drug manufacturing countries to gain widespread geopolitical acquiescence to the notion that their vision of drug control was a critical obligation of not only national but international governance.

While the contest to control the international drug trade preceded and outlasted World War II, the war marked a profound watershed. The war set the stage for a new era of drug control; since then, wars waged with drugs have persisted as the flip side to the misleadingly named “war on drugs.” World War II and the US wartime mobilization altered the balance of power among drug manufacturing countries and between manufacturing countries and states that produced raw materials for the international drug trade. The United States emerged from the war a global drug giant, the largest manufacturer, producer, and distributor of pharmaceuticals in the world. This gave it unprecedented leverage over former allies and enemies alike. By the war’s end, the country’s primary prewar manufacturing competitors, Germany and Japan, found their drug industries largely destroyed and under American occupation. In coca growing countries such as Peru and Bolivia, the war’s impact was also dramatic as the United States consolidated its position as the primary purchaser of drug raw materials, primary supplier of much-valued finished goods, and influential advocate for the aggressive regulation of the drug market. In the process, drug control became a powerful weapon for advancing American imperial might.

This chapter tells the story of these transformations by tracing the US government’s effort to control one particular group of drug commodities, those derived from the coca plant, as an anchor for a broader description of how the geography and political economy of the international drug trade was disrupted by the war, how US government economic warfare initiatives sought to capitalize, and how this shaped interactions with countries like Bolivia and Peru, both important players in the longer history of drug control. If we date the drug war to this era, almost a full three decades before President Richard Nixon famously declared a “war on drugs,” it becomes clearer how the drug war itself and the economic order it entrenched helped fuel the rise of an American empire.

DRUGS AND DEFENSE MOBILIZATION

The importance of drugs to war mobilization was self-evident to contemporary government officials and to representatives of the private sector pharmaceutical firms with whom they collaborated. Two days after President Franklin Delano Roosevelt called on the US Congress to declare war in response to the bombing of Pearl Harbor, the head of the Federal Security Administration (FSA) addressed members of the American Pharmaceutical Manufacturers’ Association (AmPharMA) at the prestigious Mayflower Hotel in Washington, DC. The FSA was tasked with managing health and safety programs related to national defense. In his speech, Administrator Paul V. McNutt celebrated previous government foresight in acquiring ample stocks of opium, quinine, and other drugs deemed essential to war making, such that by December 1941 the Treasury Department’s vaults stored a three-year supply of opium. Existing stockpiles were impressive, but not sufficient. The war threatened to disrupt the supply of “key drugs hitherto imported from abroad,” McNutt explained, and highlighted the urgency of developing new sources of supply, particularly in the Western Hemisphere.3 Earlier that year the FSA administrator had already called on drug manufacturers to emulate the armaments industry and work together to make America “the drug arsenal of the civilized world.”4 McNutt explained the direct importance of drugs for war: “Medical munitions these might be called; for they are munitions in just as true a sense as any held by our Government in military arsenals . . . they are as much a part of preparedness as tanks and planes and guns.”5

This description of drugs, as a weapons arsenal for advancing an American model of civilization, attests to the enormous value drugs held in 1941 for both state making and war making. War had always provided a stimulus to technological innovation in the drug field, but twentieth-century world war spawned what business historian Alfred Chandler has termed a “pharmaceutical revolution.”6 By the 1940s, this revolution produced a “cornucopia of new drugs,” with government-subsidized research and the mass production of vitamins, hormones, sulfonamides, penicillin, and other antibiotics radically changing wound healing, treatment for infectious disease, and government and corporate collaboration in the pharmaceutical industry.7 The war also galvanized research for synthetic drug alternatives to “replace natural products from the tropics” in an effort to avoid international dependency on materials deemed essential to public health and national power.8 Such vulnerabilities, for instance, spurred German research during the war that led to the creation of Demerol, a potent painkiller and synthetic substitute for opium. The US Army Medical Corps seized this research in Germany in 1945 and delivered it to American “chemists, pharmacologists and other medical scientists.”9 Access to pharmaceuticals (and industrial secrets) was one critical determinant of a nation’s capacity to thrive. War caused injury, hunger, and disease. Drugs promised to alleviate pain, cure infection, and stimulate a greater capacity of productive labor, whether in the mines, the factories, the fields, or on the battlefront. One contemporary neatly captured this widespread sense of the holistic interdependence of societal well-being and pharmaceuticals: “Competent protection of fighting men from disease demands the competent protection of civilians.”10

The US government began accumulating a drug arsenal as early as 1935, when the eventual thirty-year reigning head of the then five-year-old Federal Bureau of Narcotics (FBN), Commissioner Harry J. Anslinger, created government stockpiles of narcotic drugs in anticipation of war.11 These stockpiles ensured against shortages that occurred when international drug supply networks were disrupted by hostilities. They also contributed to US economic and diplomatic leverage, for example, when the nation “virtually cornered the opium market during the war years,” driving the price up by some 300 percent.12 As early as December 1939 Commissioner Anslinger reported that sufficient narcotics were stored in Treasury Department vaults to supply domestic demand and to “take care of the whole Western Hemisphere.”13 When the United States officially entered the conflict in 1941, these enormous stocks were already being used to “take care of the medical needs of a lot of our friends.” As Anslinger informed Congress: “I mean South America, particularly. We have helped out the Netherlands Indies, Russia, and other sections of the world which were formerly supplied by the manufacturing countries of Europe. I do not know what the sick and injured of some of these countries would do if it had not been for our reserve stock.”14

FIGURE 2. World War II propaganda poster for the construction of a pharmaceutical manufacturing facility.

This testimony, just ten days after the bombing of Pearl Harbor, revealed how war preparation and war increased the US government’s influence over the international drug trade. Anslinger echoed FSA Administrator McNutt when he rhetorically queried drug industry officials: “But is it our job—the job of you and our government—merely to supply the continental United States? Or will we become the arsenal for medical munitions on the public-health and medical front for all the Americas?”15 The capacity to supply drugs and enforce regulatory compliance was both a source and manifestation of economic clout in the drug market.

This economic influence was upheld in part through seeking enforcement of international drug treaties. The US FBN had taken measures to ensure “that treaties will not fall apart during the war,” in part by continuing to monitor the international narcotics trade through a system of import and export certificates. Moreover, “Being the only manufacturing nation in this hemisphere, we are able to keep international control functioning on this side of the Atlantic.”16 Wartime exigencies transformed what had previously been an international regulatory effort to control a few select pharmaceuticals, into a far more expansive effort premised on a vision of total mobilization. The FBN’s original mandate was to ensure adequate supplies of narcotic drugs for domestic scientific and medical uses and to police the unlawful importation and circulation of narcotic drugs.17 War brought other priorities to the fore. When the war broke out, opium was one of two primary categories of “narcotics” targeted for control by both national and international authorities. The term “narcotic” in this context was derived from a history of legal controls rather than medicinal qualities.18 Since the first international drug convention in 1912, “narcotic” drug control had targeted poppy plants, coca leaves, and drugs derived from them, including opium and cocaine. Following the ratification of the Convention for Limiting the Manufacture and Regulating the Distribution of Narcotic Drugs (also referred to as the 1931 Geneva Convention), this expanded to include a growing number of synthetic substitutes like codeine.19 In terms of the “narcotic” drug arsenal, along with its virtual opium monopoly, by early 1942 the FBN reported the United States had similarly secured adequate supplies of coca and rapidly became the primary supplier of cocaine to Allied nations and “liberated territories.”20 Relatively early in the conflict the United States secured adequate stocks of narcotic drugs with which to supply its own and Allied countries’ war efforts, while being in a formidable position to deny enemy access to these valuable commodities—something the FBN was actively doing.

However, the war dramatically expanded the reach of drug control to include an array of pharmaceuticals that, while not classified as narcotics, were nevertheless deemed crucial for waging war, and the FBN’s influence grew well beyond its previous jurisdiction. The National War Productions Board granted it authority over drug allocations for national defense and Commissioner Anslinger was directly involved in setting “wartime policy for the procurement of all drugs” and in decisions regarding “Allied drug requirements.”21 When asked to clarify his concerns over wartime budgetary constraints and whether the FBN’s activities were “not especially related to the war effort” but rather “national welfare,” Anslinger was quick to point out the interconnectedness: “Our work with respect to critical and strategic materials all ties into the war effort.”22 As the leader of a relatively young bureaucracy, Anslinger successfully argued the importance of drug control to national security and, in doing so, added to the FBN’s (and his own) growing influence.23 The labels “critical” and “strategic” were defined by the Army and Navy Munitions Board as being materials “essential to national defense,” with the strategic category referring to materials whose supply was dependent in whole or in part on sources outside the United States, while critical referred to materials essential for war but for which supply was not foreseen to be “as great a problem.” This directly influenced the government’s approach to the drug market. While world supplies of opium came from British India, Turkey, Asia, and Yugoslavia, the existing surpluses in US government stockpiles rendered the drug “critical” rather than “strategic.” The only drug appearing on the list of strategic materials was the antimalarial quinine, essential for inoculating soldiers deployed to tropical areas. Before the war 95 percent of the raw materials used to manufacture quinine, cinchona bark, was grown in the Dutch East Indies (now Indonesia) and concern over supply disruptions were well founded.24

In practice, contemporary officials considered a wide array of pharmaceuticals, both narcotic and nonnarcotic, to be essential to war mobilization, and the terms “strategic,” “critical,” and “defense material” were often used interchangeably to describe a wide array of drugs deemed important to maintaining national health, economic power, and strategic advantage. In addition to narcotics stockpiles accumulated under Anslinger’s early reign, in 1941 the US government identified a number of essential drug raw materials for stockpiling, including “50,000 pounds of aconite root, 200,000 pounds of belladonna leaves and 60,000 pounds of roots, 200,000 pounds of ergot rye, and 675,000 pounds of red squill.”25 The production, stockpiling, and market controls involving drugs during the war were driven by pharmaceuticals’ medicinal powers, but more importantly the focus and orientation on certain drugs was dictated by concerns over ease of access to raw materials prioritized for government war mobilization.

WAR AND THE WORLD DRUG MARKET

The war wrought a profound shift in the geography and political economy of the drug trade, and the US government and pharmaceutical industry gained the advantage. The principles and logic of international drug control became firmly tied to US national security and expansionist economic priorities. Before the war the world’s pharmaceutical markets were dominated by colonial powers—particularly the United States, the Netherlands, England, and Germany—that were dependent on the steady flow of raw materials from regions across the global South. From the coca-rich Andes of Peru and Bolivia, to poppy fields in India and Turkey, to cinchona plantations in the Philippines and the Dutch East Indies, drug raw materials grew in regions that were especially vulnerable to wartime trade disruptions; some were outright colonies, others were dependent on exporting cash crops to pay for the importation of many basic goods, including medicines. The war disrupted and transformed these trade networks. In the first months of 1942, Japan’s rapid military advance into the Philippines, Malaysia, and the East Indies cut off European and American access to raw materials from their colonies in the region, leaving them scrambling for alternatives, or languishing without drugs. In the West, the Allied blockade and German submarine warfare further impinged on a once-robust transatlantic pharmaceutical trade.

Examining the impact the war had on the circulation of one particular set of drug commodities—coca leaves and the various manufactured goods derived from them—offers a revealing account of the intersection of war, drugs, and US power. The war facilitated the consolidation of US control over all coca-derived commodities circulating on the international market, engulfing in particular German and Japanese competition. As one of two categories of narcotic drug targeted for international controls before the war, there is uniquely rich historical documentation recounting the international flow of coca commodities before, during, and after the war that provide insights into war-wrought change. Moreover, as one of two categories of narcotics located firmly in the Western Hemisphere, and with Latin American resources being newly valued as critical to US war mobilization, examining shifts in the coca market also provides perspective on the nature of US economic and political expansion at mid-century. Finally, while this account traces the circulation of coca commodities from the cultivation of coca plants through to the distribution and consumption of goods derived from them, it also offers insight into how any particular drug’s value was embedded in broader social, political, and economic visions that increasingly relied on laboratory-manufactured drugs to advance economic development and national power.

In the 1930s coca leaves had been circulating on the international market for more than half a century and constituted the basic raw material for the manufacturing of three other commodities: crude cocaine, cocaine hydrochloride, and a soft drink flavoring extract manufactured for the Coca-Cola Company.26 Despite competition from Japanese and Dutch farming on colonial plantations in the Pacific, the largest national cultivators of the coca leaf remained within the geography of coca’s origins, in the semitropical slopes of the Andes Mountains of Peru and Bolivia. When the war began, the Netherlands East Indies, Bolivia, and Peru produced an estimated four-fifths of the total world trade in coca leaves.27 Bolivia cultivated coca leaves primarily destined for a regional market sustained by indigenous peasant communities and mine workers. Peru also supplied the Andean market with coca leaves. The circulation of coca leaves in the Andes reflected patterns of traditional use and consumption, interwoven with the impact of the market value of the leaves internationally. In the Andes, coca was typically consumed in its natural leaf state. Coca leaves were chewed, steeped as maté infusions, constituted components of ritual practice, and circulated at times as currency, both in the form of wages or as payment in exchange for goods. The vast majority of coca leaves being cultivated were consumed in this market.28 Unlike in Bolivia, however, substantial quantities of Peru’s coca leaves were cultivated for export. Peru was the largest exporter of coca leaves on the world market and those leaves were exported primarily to manufacturers in the United States.29

Although most Peruvian coca leaf exports went to the United States, Peru was unable to export any crude or refined cocaine to the US market. US narcotics law, since the passage of the 1914 Harrison Narcotics Act, limited national imports to raw materials (coca leaves) and excluded refined drugs (cocaine hydrochloride) and semirefined drugs (crude cocaine)—the manufacture of any narcotic drug for the US market had to be done in the United States by registered importers and manufacturers monitored by the US government. Peruvians did have some limited participation in the manufacturing and export of crude cocaine to Europe, where pharmaceutical companies refined it. Thus, when the war began, the Andean coca leaf market was characterized by the production of raw materials for regional consumption, as in Bolivia, or, in Peru’s case, as also a primary supplier of raw material exports (coca leaves and crude cocaine) to US and European drug manufacturers.

Outside the Andes, coca leaves grown on colonial plantations in the Pacific were the primary source of supply for all major drug manufacturing countries except the United States, namely Germany, Japan, France, and the United Kingdom. Japanese cultivation of coca leaves on colonial plantations in Formosa (Taiwan), Okinawa, and Iwo Jima supplied that nation’s pharmaceutical industry. Dutch-controlled Java, Borneo, and Sumatra furnished the bulk of coca leaves imported by European manufacturers (along with limited quantities to the United States). While the Andes was the ecological home of coca leaves, nineteenth-century Dutch colonists experimented with transplanting coca seedlings to the fertile soils of the East Indies (now Indonesia) and stumbled across a strain of particularly high-alkaloid-content coca leaf that they cultivated for export. These leaves were uniquely suited to manufacturing cocaine hydrochloride and rapidly came to dominate the international trade geared toward the manufacture of medicinal cocaine.30

Nevertheless, in the 1930s the United States remained the largest manufacturing global importer of coca leaves, and these came primarily from Peru. In terms of the North–South distribution of economic power, Europeans and North Americans controlled the manufacturing and international distribution of products derived from coca leaves grown in South America and Southeast Asia. But Americans could claim the most robust market for coca leaves since imports were destined not only for the manufacturing of pharmaceuticals, but also for the large-scale production of a flavoring extract for the Coca-Cola Company. In the United States, only two pharmaceutical companies were legally authorized to import coca leaves: Merck & Co., Inc. and Maywood Chemical Works. Merck imported coca leaves from both Peru and Java, which the company’s chemists used to manufacture pharmaceutical-grade cocaine. Maywood imported coca leaves exclusively from Peru, and after extracting and destroying the cocaine alkaloid (to comply with federal narcotics law), the pharmaceutical company transmuted the remainder into a “nonnarcotic” flavoring extract for Coca-Cola. A combined effort by lawyers for the pharmaceutical industry, the Coca-Cola Company, and Commissioner Anslinger of the Federal Bureau of Narcotics secured this concession for “special leaves” in the 1931 Geneva Convention, an exceptional regulatory moment when the legal uses of coca in the drug trade were defined internationally as encompassing both medical and scientific needs, as well as production of a coca-based flavoring extract for the iconic soft drink.31 By WWII, coca leaves imported into the United States for this purpose consisted of almost twice the volume of leaves imported for medical or scientific use. In both the United States and Europe coca-derived commodities were manufactured for domestic consumption and for reexport. And only at this last stage of the coca commodity circuit did Andean countries reenter as consumer markets for these finished goods, whether as medicinal cocaine, or in bottles of Coca-Cola.32

World War II disrupted and transformed the trade circuits through which coca leaves, crude cocaine, pharmaceutical-grade cocaine, and Coca-Cola all flowed. The Japanese occupation of Java, combined with British and American naval blockades of the Atlantic, cut off the European market from supplies of coca leaves and crude cocaine. Germany, the largest European manufacturer and wartime target of naval blockades, was hit hardest. Allied intelligence reports speculated that even reserve stocks inside Germany were being depleted: “Since 1941, Germany has certainly not been in a position to procure coca leaves . . . stocks must have been drawn upon in order to meet requirements in the years 1941 and 1942.”33 From 1936 to 1939, the European continental countries imported an average of 71 tons of coca leaves each year from South America and Asia; however, by 1941 the only trade consisted of a scant few kilograms reexported from one European country to another. By 1943, the League of Nations reported “the countries of the continental group” were unable to procure coca leaves.34 Europe’s access to crude cocaine was similarly disrupted. Before 1939, Europeans were importing from Peru an average of 1168 kg of crude cocaine annually, and German manufacturers constituted the largest market. By 1942 only Spain was reporting any imports, a relatively small 136 kg per year, and by the end of the war, the US commercial attaché in Peru reported that the “great bulk of the exports” were going to Allied countries, primarily England, “with Spain in second place.”35

With the Dutch East Indies under Japanese occupation, Peru remained the only producer of coca leaves for the world market, and cut off from Europe, the state found itself increasingly dependent on US purchases and subject to the US legal proscription against importing manufactured narcotics. In turn, the United States emerged from the war as the world’s largest importer of coca leaves and the largest producer and distributor of cocaine. The United States used this new leverage to dictate the scale and scope of the trade and to exert political influence. In doing so, the United States implemented the structures of its vision for drug control as a constituent element of its wartime policy, and guaranteed its dominant position in the international drug trade in the war’s aftermath. Two central animating principles seem to dictate US wartime policy toward the Peruvian coca trade. First, the United States insisted on retaining its manufacturing monopoly and refused to import anything other than coca leaves from the Andes. Second, in the broader effort to undermine Axis economic power and capacity to wage war, the United States interpreted any signs of ongoing Axis trade with South America as evidence of criminal conspiracy and threatened coercive measures to punish those responsible.

Despite mounting stocks of both coca leaves and crude cocaine in Peru, the United States denied repeated requests from Peruvian exporters to sell leaves that had already been converted into cocaine. The war placed the United States in a powerful position to hold onto its drug manufacturing monopoly and further entrench a relationship whereby Andean raw materials remained the region’s primary export. The US drug industry depended on an array of Latin American basic supplies: “Important items from Latin America include cinchona bark for quinine; ipecac, valuable for its alkaloid emetine; stramonium, an important substitute for belladonna and also a valuable source of scopolamine; coca leaves for cocaine; fish livers for vitamins, glandulars (thyroid, pancreas, and so on); and cocoa beans, of which the shells and residue are important for the production of caffeine.”36 This was a phenomena exacerbated by the war, but had historical roots in the impact of the 1931 Geneva Convention, which the Peruvian minister of finance and commerce complained had cut Peru’s share of the international cocaine market from 40–50 percent to as low as 3–4 percent.37 In 1940 the Peruvian commercial attaché appealed to the Federal Bureau of Narcotics, which had “the power to determine from which states US firms could buy raw material and to which countries American manufacturers could export,” to authorize more US companies to import Peruvian coca leaves.38 The FBN rejected the request and refused to grant any new import licenses on the grounds that it would make drug control more difficult, in effect a justification for maintaining a US manufacturing monopoly. It also dangled a thinly veiled threat by suggesting the United States had already done Peru a favor by ending a Department of Agriculture project to grow coca in Puerto Rico so as to “prevent upsetting the economic status between the United States and Peru.” This project, the FBN official noted, could be easily resumed.39

MAP 1. Coca leaf cultivation and derivative manufacturing, 1946.

The war only strengthened the international drug manufacturing hierarchy the United States sought to entrench. Thus, when Peruvian Minister of Finance David Dasso argued in 1942 that Peru should manufacture its own cocaine for the US market and proposed that the United States “should buy cocaine instead of the cocoa [sic] leaf from Peru since processing the leaf for cocaine was a relatively simple matter,” he was resoundingly rejected.40 In response to Peruvian efforts to expand access to the US market, the State Department declared, “It would seem the answer to Mr. Dasso should be that it is up to Peru to make the concessions, not the United States.” This claim was backed by the US accusation that any increase in Peruvian drug manufacturing “would merely go into the illegal trade,” which at the time was defined as a willingness to “sell illegally to Germany and Italy, which are in desperate need of cocaine.” Characterizing Peruvian export practice—meeting an acknowledged medical need (and hence Axis country strategic import)—as “illegal,” the State Department reframed an economic and political struggle into a language and practice of delineating (and ultimately prosecuting) criminality. The United States even threatened to cut “Peru off from all sources of narcotic drugs” and “stop its purchases of coca leaves” to force Peruvian compliance.41 Thus the United States was able to use its economic and political leverage to entrench a particular economic order that incorporated a definition of criminality premised on political loyalties.

But the US government also made some concessions. The US-Peru Trade Agreement, signed in May 7, 1942, lowered the import duty on coca, increasing profits for Peruvian exporters. When the FBN complained about this loss of tax revenue (a key component of its budget), the Treasury Department explained, “there were overpowering considerations from the point of view of policy which guided the Committee in approving the concession.”42 As this episode shows, profit was not measured exclusively in economic terms; the United States also sought to maintain control over the drug trade to secure the political stability of its trading partners and establish the long-term alignment of Latin American countries like Peru with the United States.

Drug control then had multifaceted value: at once economic, medical, and diplomatic. At the most basic level it promised to supply or obstruct the flow of medicinally valuable pharmaceuticals in the context of a widespread spike in demand generated by war. Cocaine, for example, was valued in part as an unparalleled local anesthetic. When Peruvian exporter Andrés Soberón’s crude cocaine stocks began to accumulate with the loss of access to the Italian and German markets, he invoked the drug’s wartime medical value in his failed bid to the US State Department and the FBN to sell his semirefined drug to the United States for further refining: “Cocaine is indispensable for attending to those injured in the War and we are sure, based on letters we’ve received from Europe, that in Russia and all European countries there is a great demand for this product.”

Soberón appealed on behalf of the war-injured, even while making an economic entreaty by suggesting this Peruvian-US trade would enhance the capacity of the United States to meet European and Russian “demand.” The United States was adamant in its refusal to import Peruvian crude cocaine, although it did flex its diplomatic muscle and offer to put Soberón in touch with interested buyers in the “Government of the Soviet Socialist republics.”43 A year later, Soberón expanded his appeal through an invocation of the trade’s importance for maintaining hemispheric solidarity: “[W]ishing to contribute to the defense of America, I offer 600 kilos of crude cocaine.” Again his request was rejected.44

The war augmented US power in the international drug trade, and officials did not need to circumvent or renegotiate the national drug regulatory framework’s long-term orientation toward protecting the interests of US manufacturers. This was especially true in relation to the coca leaf and cocaine market. The United States continued to import coca leaves from Peru, despite shunning Peruvian crude cocaine. Peru remained the “principal source” of US imports of coca leaves and the war boosted the volume of this trade.45 In March 1942, one week after the Japanese conquest of Java, the commissioner of the FBN gave an update on the state of the coca market: “As you know, coca leaves, an important defense material, are used in the production of cocaine, a narcotic drug which is indispensable in the treatment of diseases and injuries to the eyes. No substitute for cocaine has yet been discovered.”

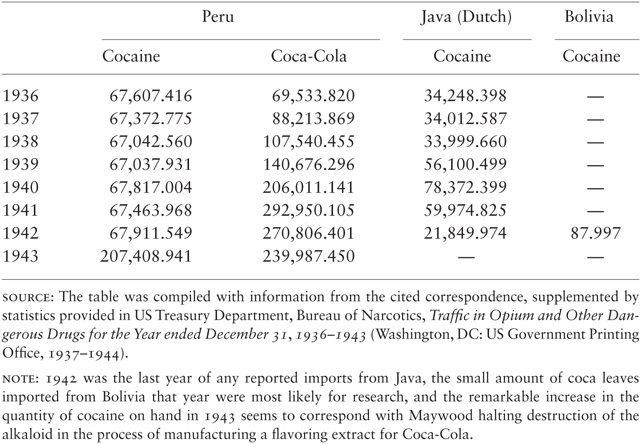

Anslinger wrote that despite the war-caused disruptions to Merck’s supply of coca leaves, “We now obtain from Peru a quantity of coca leaves sufficient to replace the amount formerly imported from Java.” As with the government-directed accumulation of other raw materials deemed valuable to war mobilization, and even though it anticipated “no shortage for the duration of the war,” the FBN authorized the expansion of coca leaf stockpiling. Anslinger reported, “The Bureau of Narcotics has instructed Maywood Chemical Works to recover all of the raw cocaine obtained from coca leaves.” In other words, even though existing stocks of raw materials could easily meet normal annual demand for medicinal cocaine, the FBN authorized Maywood to stop destroying cocaine alkaloid extracted in the process of making a flavoring extract for Coca-Cola. In this striking move, the United States invoked wartime necessity to stockpile quantities that exceeded the annual quotas it was entitled to hold under the 1931 Geneva Convention, and tapped large supplies of coca leaves that were easily accessible because of the “special” status Maywood’s leaves had been granted under the international treaty. The raw cocaine that could be obtained from these leaves imported for the express purpose of manufacturing a soft-drink flavoring extract, Anslinger reported, amounted to “approximately four times the normal medical needs of the country.”46

TABLE 1 US COCA LEAF IMPORTS AND USES, 1936–1943 (in kilograms)

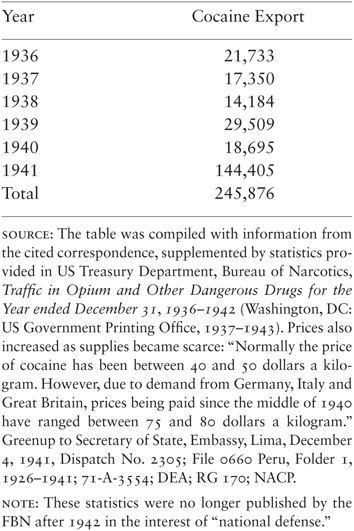

As raw material stockpiles began to accumulate, this reserve supply of drugs put the United States in a powerful economic and political position as the major world-supplier of cocaine. US manufacturers replaced European producers in the world market, and US cocaine exports increased dramatically. By 1941 US exports had increased by more than 600 percent over quantities exported just five years earlier. Before officially declaring war, the United States had been “manufacturing a large quantity of cocaine for Russia on the Lend-Lease program.”47 By 1944, as Anslinger testified before Congress, the United States was supplying “Russia with all her cocaine needs, both for military and civilian use, because Russia has been separated from her market. We have supplied Russia and India and a number of parts of the British Empire, and in the case of India, we have received in turn an equivalent amount of opium. We insisted upon that to keep from dipping into our reserves too deeply. We have been able to give this help. Now we are confronted with supplying some of the liberated territories.”48

TABLE 2 COCAINE EXPORTS FROM THE UNITED STATES, 1936–1941 (in grams)

The international consumer market for American-manufactured pharmaceuticals expanded considerably as US officials worked with private companies to “help” fill a drug vacuum in Europe, the Soviet Union (USSR), and colonial markets formerly supplied by the British Empire. This was true not only with regards to cocaine, but also in relation to another exceptional coca-derived commodity: Coca-Cola.

Wartime drug control provided an opportunity for select US corporations with an investment in the coca market, such as Merck, Maywood, and the Coca-Cola Company, to align themselves closely with the interests of the US government and benefit from the collaboration. Much as government intervention prevented the importation of crude cocaine into the United States, when the Peruvian commercial chancellor tried to offer the Coca-Cola Company “de-narcotized” coca for sale, the company’s president contacted the head of the FBN, suggesting that Peruvian interest in the market might be exploited to pressure for compliance with “international control authorities.”49 Coca-Cola, the drink itself, became officially allied with the national cause. Following Pearl Harbor Robert Woodruff, the head of the Coca-Cola Company, declared that all men in uniform could get Coca-Cola for five cents wherever they were serving. With a Coca-Cola executive appointed to the sugar rationing board, by 1942, “Coca-Cola was exempt from sugar rationing when sold to the military or retailers serving soldiers,” while the rest of the soft drink industry was forced to reduce their consumption. Helping to fulfill Woodruff’s promise, sixty-four Coca-Cola bottling plants were established “on every continent except Antarctica” during the war, largely subsidized by the US government. Coca-Cola representatives were given the status of “technical observers”—civilians servicing the military—while the army paid for the transportation costs of Coca-Cola and for military technicians who helped construct Coca-Cola plants for the deployed troops. German and Japanese prisoners of war were even assigned to work in these newly constructed bottling plants.50 The collaboration between the United States and companies supplying American troops on the battlefront was accompanied by an equally striking government program to capitalize on wartime disruptions in neutral countries far from the battlefront. Nowhere was this more apparent than in US efforts to promote the expansion of its pharmaceutical industries into Latin America.

WARTIME MARKET DISRUPTIONS

The war-wrought transformations in the circulation and flow of raw materials destined for North American and European pharmaceutical manufacturers produced fundamental disruptions in the flow of finished drugs. The impact on Germany was particularly dramatic. The world’s longest established and most profitable pharmaceutical industry could not acquire drug raw materials, had its industrial production under attack, and confronted US economic warfare campaigns against Germany’s drug production and distribution networks in neutral and Allied territories. Entering the war, Germany dominated the international drug market, including an impressive presence in the Western Hemisphere. While Germany trailed behind England and the United States as the third “major trading partner with South America,” the country was the region’s largest supplier of pharmaceuticals.51 A report to the secretary general of the League of Nations in 1943 noted the wartime dramatic shift in pharmaceutical manufacturing clout. “Germany, the chief distributor of drugs before the war, now exports only insignificant quantities of narcotic drugs.”52 By the end of the war American military assessments were more blunt. “German Pharmacy Kaput!” reported the Chief of the Medical Branch, US Strategic Bombing Survey after reviewing the impact of bombing on the infrastructure of the once globally dominant German pharmaceutical industry.53

Early in the war, however, German dominance of the drug trade was a serious cause for concern. Writer and investigative journalist Charles Morrow Wilson lamented in 1942 that unlike American businessmen, the “Germans took pains to capture Latin-American markets for legitimate medicines and pharmaceuticals” during the first half of the twentieth century. “Even during the war years of 1939, 1940, and 1941 the German position has been maintained. Actually the Nazis have been making use of their drug trade with South America to provide a source of revenue for propaganda and fifth column activity.”54 These frustrations and fears echoed those expressed by US officials dispatched to South America in December 1941 under the auspices of the newly constituted Board of Economic Warfare (BEW). The “entire Latin American economy was part of [the BEW’s] concern” because, as the director of the Council on Foreign Relations explained, the region was “a storehouse of strategic raw materials.”55 However, agents rapidly discovered that while Latin American countries for the most part were willing to cooperate with US economic warfare initiatives in the region, they encountered significant obstacles when it came to limiting the flow of German pharmaceuticals. As the US ambassador to Bolivia confided to the Secretary of State in 1943, “Indeed, it is likely that the failure to eliminate the Nazi dominance in the drug field will assist Nazi interests to continue to have their way in other commercialized fields in which they remain powerful.”56

Whatever success the United States achieved by dominating the drug raw materials market was undermined by its inability to dominate the consumer market for finished goods. As nations battled to control the flow of the world’s resources, raw materials and manufactured goods together constituted the critical inputs for maintaining overall societal health; both production and consumption mattered to this equation. Government planners embraced an economic calculus premised on balancing “the allocation of manpower and raw materials” in the service of war. The economic reasoning constituted an ideology that viewed humans and natural resources together as the raw material inputs to national power, and their healthy presence needed to be sustained for profit and national security. In the United States, before the war was over, “the nation’s economic machinery had been reorganized throughout, from the acquisition of materials to the final distribution of the end-products among our armed forces, our allies, and our civilians.” And to ensure a healthy flow of material inputs, as the US military explained, “it became necessary for us to exercise a stabilizing influence on the domestic economies of countries most affected, particularly in Latin America.”57 Thus economic warfare in the Andes grew out of this grand imperial vision where rivalries between the United States and Germany in the drug field were driven by the value these commodities held for cultivating human and natural resources in the global competition for national dominance.

The war marked a major economic turning point with the United States emerging as a net importer rather than exporter of raw materials.58 While the United States had always cultivated a hegemonic economic position in the Western Hemisphere, the war provided an unprecedented stimulus to trade when the conflict disrupted the flow of raw materials from Southeast Asia. As one observer commented, “we must have tropical products to win the war and to keep the peace . . . [which means] we are seeing the birth of an entirely new inter-American economy.”59 The Nation’s Business echoed this sentiment: “War needs of the United States have speeded up production in the South American countries . . . [and] we will help in adjusting the national economics of those which responded to the war effort.”60 Some saw the US effort to mold Latin American economic development toward US priorities as potentially coercive and unwelcome: “We must beware of the temptation to convert hemispheric defense into a new streamlined imperialism.”61 However, this did not slow the economic war, as the desire to undermine German power became firmly tied to the long-term development objectives of the United States in the hemisphere.

Battles over the drug trade in the Andes were waged in the context of the overall importance of these economies to the war effort. At the beginning of the war Bolivia and Peru had significant economic ties to both the Allied and Axis powers. As the United Nations would later report, “Before World War II there were substantial investments in Peru owned by German, Italian and, to a smaller extent, Japanese nationals.” However, by the end of the war, “the only substantial foreign business investments” belonged to the United States and Great Britain. Even before the war US investments exceeded German, Italian, and Japanese investments, and by 1935 the US mining company Cerro de Pasco Copper was “by far the largest foreign-owned mining concern in Peru.” The United States was the primary source of capital behind Peru’s mining industry, which accounted for 20 percent of world production. More than half of the total labor force worked for foreign-owned companies, and Cerro de Pasco alone accounted for over a third of the total, producing “more than half the metallic mineral output of the country.”62 In an overview of its raw materials policy in Peru, the US military even drew a comparison with the British Empire’s monopoly over tin production in Thailand, noting that in addition to domestic production the United States was intimately involved in the “commercial control over production in other countries” such as the Vanadium Corporation of America, which controlled almost “the entire Peruvian output” of the steel alloy.63

In Bolivia “the basis of the country’s economy was tin mining.”64 Before WWI, the “Germans [had] acquired a virtual monopoly in several branches of commerce and had made themselves almost indispensable to the economic life of the country.” Yet like Peru, the United States was also a formidable power in Bolivia before the war. The Bolivian tin mining industry was the main source of internal tax revenue in the country and the largest company, Patiño Mines and Enterprises, Inc., registered in the United States and financed by US capital, was responsible for 40–45 percent of the national output. Prices for Bolivian tin, which accounted for three quarters of the country’s exports, suffered during the Great Depression. “Foreign exchange receipts decreased sharply,” and increasing national debts acquired from “substantial borrowing abroad . . . practically all of it from the United States” placed the United States in a position of considerable economic influence. Tin prices recovered throughout the 1930s and shot up further during World War II. In 1940 the United States negotiated a five-year tin contract with Bolivian tin producers, and secured the country’s entire output of tungsten and surpluses of antimony, tin, and zinc.65

US investments in Bolivia and Peru in extracting antinomy, tungsten, tin, quinine, rubber, and petroleum were heavily influenced by the logic of economic warfare. When American policymakers devised wartime economic policy in the region, ensuring the conditions necessary to sustain these industries was paramount. For instance in Bolivia the United States launched public health programs that specifically targeted rubber and quinine producing regions in the hopes of maintaining a healthy workforce to extract resources essential for US war making.66 As the Bolivian ambassador to the United States explained, “Tin and rubber were needed for planes and tanks; the factories producing cannons and ammunition needed Bolivian tungsten; and other commodities, mainly foodstuffs for American soldiers, were required. In this way, the manual work of the Bolivian Indians of the Andes suddenly acquired a transcendental dimension for the life and the defense of that great nation.”

Minerals including tin, antimony, and tungsten accounted for 98.3 percent of the country’s exports, and demand for such metals was “always large during war periods.”67 Bolivia possessed the only hemispheric source of tin and, spurred by war-induced global tin shortages, the United States built a tin smelter specifically for Bolivian ores.68 Before the war the British had been the primary smelters of Bolivian tin, which they then sold to the United States. The war facilitated the emergence of a US smelting industry and the end of American dependence on British manufacturers.69 During the war the United States became the sole purchaser of Bolivian minerals, replacing the United Kingdom as Bolivia’s primary tin export market, which gave the United States considerable diplomatic leverage particular since wartime US stockpiling meant “that market power had shifted decisively from producers to consumers.” While there were rumblings among Bolivian nationalists (particularly strong among the mine-workers organizations) that the “country had become a virtual colony of the United States,” Bolivian officials also sought to capitalize on their newfound importance.70 The BEW mission reported in December 1941 that “Bolivian authorities feel that since Bolivia is contributing to the defense effort by making available vitally important minerals, it is a responsibility of the United States Government to see to it that the mining industry (eighty percent of Bolivia’s import needs) is promptly provided with whatever equipment may be necessary.”71 As the Bolivian ambassador emphasized to his US colleagues, the Indian mine worker “was a true soldier of the cause, whose function ran parallel to that of the soldiers who fought in the trenches, defending the ideals and interests of the Allies.”72

Such appeals gained traction in the wake of what came to be known as the Cataví Massacre in December 1942, when a tin miners’ strike demanding “better housing, wages and medical care” was violently repressed by the government, leaving many dead.73 Historian Laurence Whitehead suggests American officials saw their subsequent intervention as “Good Neighborly” rather than imperial, when they determined that “labor peace in the mines was of urgent concern for those in charge of Allied procurement” and helped organize an investigation headed by a Joint US-Bolivian Labor Commission.74 The Assistant Secretary of State invited Judge Calvert Magruder to chair the commission, describing its goal as being the “double end of improving conditions of labor in Bolivia and assuring a steady production of strategic materials for the United States.”75 The investigators found the “standard of living is notoriously low” among the mine workers and recommended changes in labor policy, which ultimately led to the insertion of labor clauses into the US tin contract. The report also noted one raw material input (coca leaves) that might be a contributing factor to the paltry conditions: “These leaves contain a small amount of cocaine and their chewing is claimed to deaden sensory nerves, quiet hunger pains, temporarily stimulate energy, increase the power of endurance, but do constitute a degenerating force that markedly reduces efficiency.”76 The issue was set aside as something needing further study (and would be taken up after the war by the United Nations), but the problem of labor efficiency and its dependence on healthy consumption was of central concern to US officials, and the circulation of drugs—deemed healthy or harmful—became central to questions of national security.

In this way, the war highlighted the already intimate connection between the mining and pharmaceutical industries. Increasingly a vital part of sustaining the “transcendental” contribution of Bolivian Indians to the war effort entailed steady supplies of pharmaceuticals. For instance, as part of a Bolivian effort to secure national benefits in an industry dominated by foreign capital, companies like Patiño Mines were subject to the Bolivian “Mineral Code.” The code stated that foreign “mining enterprises employing more than 200 workers and located more than ten kilometers from the nearest town must provide living quarters, health services and food to the workers.”77 A healthy industry required healthy workers, and here Germany’s early competitive dominance was stark. In the Andes the mining industry constituted the largest “consumer” market for pharmaceuticals and doctors working for the “large mining companies” continued, despite economic warfare proscriptions, to place orders with German pharmaceutical manufacturers. In January 1942, the US Embassy in La Paz lamented, “Bayer, Merck and Schering products had been specifically requested by the doctors working for these organizations.”78

ECONOMIC WARFARE AND PUBLIC HEALTH

US economic warfare initiatives encompassed a range of practices including the establishment of a blacklist forbidding trade with people and firms deemed to be enemy nationals or cooperating with the enemy, the preclusive buying of raw materials to prevent them from falling into enemy hands, a system of import and export controls designed to maximize trade in strategic goods, and programs geared toward developing new supplies of raw materials, such as the concerted effort to “revive a practically extinct quinine industry in Latin America” after Japanese military advances cut off Southeast Asian sources of supply.79 Thus, the BEW pursued two primary goals: weaken the enemy’s strategic materials arsenal and financial power, and reorient “Latin America’s economic activity . . . toward fulfillment of the war needs of the United States.”80

In the weeks after Pearl Harbor, the foot soldiers of the BEW traveled through Peru and Bolivia to “familiarize members of the Legation staff with the procedure in Washington for handling Proclaimed List problems.”81 In July 1941, Roosevelt had issued a Presidential Proclamation calling for the compilation of a list of people and firms who directly or indirectly aided the “enemy war machine” and participated in trade “deemed detrimental to the interests of national defense.” Between 1941 and 1945 the “Proclaimed List of Certain Blocked Nationals” was compiled and US firms and citizens were prohibited from doing business with those listed. In practice the blacklist impacted many enterprises regardless of national origin if they were accused of doing business deemed detrimental to the “national defense.”82 When the Peruvian minister of finance asked (perhaps nervously, being of Italian ancestry) for clarification on who should be put on the Proclaimed List, the BEW personnel explained it included “persons who, by their action and not by birth and such, were deemed to be nationals of Germany or Italy, and persons whose activities were inimical to the hemisphere as a whole.”83 In the effort to gain Andean cooperation, the United States framed its economic warfare policies as encompassing Axis agents, but also as a broad and flexible category that could target anyone deemed vaguely threatening to hemispheric defense.

While largely successful in relation to securing control over drug raw materials, the United States had a harder time intervening in a consumer market that until the war had been dominated by German drugs. The BEW agents discovered that manufactured drugs constituted a difficult front in US economic warfare initiatives in the Andes. Eliminating German business competition could only be effective if national governments—like Peru and Bolivia—were willing to target companies accused of ties to Axis powers, even if this entailed immediate short supplies of medicines deemed essential to public health and the smooth running of the countries’ economies. The goal of implementing the Proclaimed List in the Andes was complicated further by the fact that as of mid-1942, US pharmaceutical manufacturers had not yet extensively penetrated the South American market. Drug diplomacy therefore cut both ways. As public health was increasingly seen as a component of national security, allies like Peru could invoke the public interest to resist limitations on their trade with German manufacturers until “legitimate” substitutes could be provided. The Peruvian government refused to prevent the distribution of German and Italian “pharmaceuticals and medicinals,” and insisted an exception to the implementation of the US vision for economic warfare made sense “for such operations as might be necessary in the interest of public health and sanitation.”84 As late as February 1943, the US Embassy reported that the Peruvian government refused to cut off foreign exchange to German distributors “until we can supply American products to take the place of German preparations.”85

Similarly the US Embassy in La Paz reported its failure “to convince the Bolivian Government” to deny Proclaimed List nationals foreign exchange or to prevent the distribution of their drugs. The reason “that such efforts have so far proved fruitless is due, at least in part, to the fact the Germans control the drug trade in Bolivia and continue to import products essential to the country.” Cutting off foreign exchange to German importers would mean that the “country’s economy would be most seriously harmed.”86 By June 1942, German drug distribution had been disrupted by naval blockades and the closure of German Bayer and Schering drug firms in Brazil.87 And yet, as in Peru, by early 1943, “no replacement sources have appeared.” The US Embassy wrote explaining the gravity of the situation to the State Department: “The present drug situation is therefore most serious to Bolivia, as an absolute shortage of necessary drug products is dangerous to the general health of the country; and to the further prosecution of economic warfare policies because any dislocation of economy due to the war is immediately blamed upon the United States.”

Drugs had become critical to “national health” and critical symbols of the potential abuses and limits of US power. The US Embassy lamented, “German interests can effectively force the Bolivian Government to grant them the financial and other facilities they need.”88 The US government concluded: “in addition to being a matter concerning Bolivia’s public health, pharmaceutical products become a most important weapon of economic warfare.”89 Three months later, pharmaceuticals still remained the “knotty segment of the supply problem.”90

Two key objectives emerged in US drug warfare initiatives in the Andes.91 The first was the push for Latin American implementation of sanctions against Proclaimed List businesses involved in the drug trade. The second, a necessary accompaniment to the first, was the concerted effort to ensure a reliable replacement supply of US-manufactured drugs. The challenge was formidable as new agencies within the US government jockeyed for control over the program, as American drug companies had not yet penetrated the region, and as regional governments resisted taking action until public health (and by extension, economic production) was guaranteed. In his study of economic warfare and the pharmaceutical industry, historian Graham D. Taylor emphasizes bureaucratic wrangling between the State Department and the BEW as generating enormous inefficiency.92 In fact battles between the secretary of commerce and the vice president over delays in acquiring Latin American sources of quinine led President Roosevelt to dissolve the BEW in 1943 and replace it with the Office of Economic Warfare under new leadership.93 Despite the infighting, there was considerable agreement on the value of drugs to national security and a shared belief in the need for US intervention in nations across the hemisphere on this account. Government officials and pharmaceutical businessmen also reportedly shared skepticism “about the commercial benefits of contributing to local chemical manufacturing development in Latin America.”94 The program had to be driven by expanding both supply and demand for US-manufactured drugs.

To overcome these obstacles, staff at US embassies in the Andes worked with local governments and businesses to assess drug requirements and asked US pharmaceutical firms to compile and disseminate lists of comparable American drugs.95 Drug control brought together commercial and strategic interests while creating a network of public and private collaborators. The BEW mission reported, “Our whole program depended upon getting good commercial intelligence,” and informed the US commercial attaché in Peru that “he should use every means to get commercial information.”96 This “commercial intelligence” helped the United States gauge demand for pharmaceutical products and implement what it termed a “Drug Replacement Program,” a strategy to replace Axis products with US-manufactured drugs. Embodying a logic that continued to shape international drug regulation, it was not the chemical substance itself that made a drug desirable or undesirable, but rather the political and economic affiliations of its manufacturer. Obtaining information about national essential drug requirements was critical to the program since governments were hesitant to cut off German suppliers of pharmaceuticals until the United States was able to provide “Allied” goods—the very same drugs—as substitutes. While it began as a program initiated during the war, this market reconnaissance strengthened the US government’s desire and capacity to facilitate the ongoing expansion of US corporations into those markets.

On the Andean government side, the US commercial attaché suggested that the Peruvian Ministry of Finance create a “Commercial Department” to facilitate “greater oversight and control over stocks of drug commodities and their distribution.” As of January 1942, this new department “now has a staff of approximately sixteen men who are devoting all their time to gathering information on essential requirements, stocks, prices and related matters.” But as they began their work, US representatives complained the estimates they provided were “greatly exaggerated and that the investigating and analytical ability of the Commercial Department is not high.” Believing the capacities of US personnel to be superior, and perhaps as a way of gaining greater access to information, the BEW successfully suggested that a US officer “be placed in the Commercial Department not just to advise with but in reality to organize and direct its work.”97 By March 1943 US economic warfare objectives were gaining ground in Peru, although German-manufactured drugs continued to circulate. The Peruvian government remained unwilling to shut down German drug distribution, but did help the United States gather commercial intelligence to facilitate the replacement program. A Supreme Decree required reports from all government agencies to determine essential drug requirements and medicinal needs, and instituted a system of controls to track stock quantities and direct distribution.98 The Peruvian Ministry of Public Health also delivered product sales information for various Proclaimed List firms, which the US Embassy handed over to US business interests. Despite these efforts some imports of Axis pharmaceuticals persisted until as late as November 1943.99 There was no law requiring the private sector to report its drug stocks, and the US Embassy remained frustrated in its efforts to “ascertain the present inventories in Peru of German Drugs.”100

This type of collaboration was harder in Bolivia. There too the United States believed essential requirement figures were “grossly exaggerated,” but unlike in Peru, the BEW lamented, “There is no American community on whom the Legation can rely for help.”101 In a panicked plea to expedite licensing of US drug shipments, an embassy official wrote the State Department in January 1943: “Scarcity of American pharmaceutical products in Bolivia reaching critical stage.”102 However, by April, the embassy in La Paz had a more optimistic assessment of the prospects for economic warfare coordination. Following a brief tour of the US Vice President through the region in an effort to shore up hemispheric solidarity, US Ambassador Henry Ramsey was confident: “It appears almost certain that Bolivia will declare war and if it does we should move quickly to present a comprehensive [drug] replacement program before the country’s initial and belligerent enthusiasm abates.”

The very next day, April 7, 1943, Bolivia officially declared war on Germany. Viewing war “enthusiasm” as a boon to US objectives, Ramsey went on to suggest that the financial aspects have to be handled “before we will have much bargaining power on the matter of adequate control.” To that end, he recommended the Export-Import Bank finance a Bolivian subsidiary bank to fund the drug replacement program, setting aside government funds to help US pharmaceutical firms distribute in the Bolivian market. The campaign to finance the replacement program was taken up by the Bolivian Development Corporation (BDC), established in 1943 to stabilize the Bolivian national economy through US-Bolivian financial arrangements. The BDC was governed by a board, half of whom, including the president and vice president, were appointed by the Bolivian government and the other half, including the manager and assistant manager, by the Export-Import Bank in Washington. In a letter addressed to the US vice president seeking support for the bank proposal they explained, “[The BDC’s] most effective field of action lies in the program of economic warfare through which the democracies are attempting to eliminate the financial potency of commercial and industrial interests inimical to the democratic cause throughout the Hemisphere.” The BDC, invoking hemispheric solidarity, wanted to be able to “finance Bolivian firms” so that they might take the business of “distributing merchandise throughout Bolivia out of Axis hands and return it to Bolivians.”103

The United States was especially concerned that Proclaimed List firms were able to continue to operate by using intermediaries to disguise, or “cloak,” Axis involvement. As the United States pursued its replacement programs, dispatches continued to lament German use of business intermediaries. For instance, in November 1943 the US Embassy in Lima notified the State Department that a known “cloak for Schering interests” was importing drugs into Peru.104 In contrast, national affiliation with the United States offered legitimacy in a context where US economic warfare policies drew the line between legal and illegal participation within the economy, and by extension delineated the legal and illegal status of drugs from various origins. The embassy asked Washington for US corporations to devise a list of medicines to replace “undesirable brands” with the “names of American, British and other acceptable equivalents” as a necessary step “prior to the initiation of an offensive against these products.”105 Not only did the promotion of a “national” identity for a drug collapse the international supply networks of raw materials into the ideological property of “national” manufacturers but also, as a consequence, these manufacturers became key players in the field. The most readily available source of US pharmaceuticals necessary to replace German product lines were those manufactured by former subsidiaries of German firms in the United States, most of which had been severed from the parent company after World War I and transformed—via national affiliations—into legitimate, newly “American” companies.

In response to these worries about a German “cloak for Schering interests,” the State Department and US Embassy in Lima coordinated efforts to pass on information regarding the annual Peruvian importation of Schering’s drug products to its former US subsidiary: Schering Inc., based in Bloomfield, Indiana. The embassy deemed the information “particularly timely and helpful to it in adjusting its production and sales program to the needs of Peru.”106 These efforts clearly showed a process of criminalizing certain economic participants and select proprietary drugs premised on political and economic affiliations. To prevent German Schering from operating through “cloaks,” US Schering, a national “cloak” of sorts, was called upon to intervene. A similar policy was pursued in Bolivia. The embassy there notified the US secretary of state in 1943, “From the standpoint of enforcement of Economic Warfare policies, and realizing that the outright expropriation of German Drug interests is impractical at the present time, the only way to overcome the [Bolivian] Government’s inertia and to obtain the desired cooperation, is to actively encourage and increase the export of ethical products by United States Drug concerns. . . . Any comprehensive plan in this direction would necessarily also include an increase in exports of the American controlled Merck, Schering and other companies.”107

Expropriation reflected one wartime tactic for undermining the enemy’s economic power, a process that had already transformed both US-based drug houses, Merck and Schering, into legitimate drug providers. The effort to extend the distribution network of US pharmaceutical companies’ products (including “ethical” drugs, a contemporary term for drugs that required a doctor’s prescription to purchase) reflected another.

US economic warfare initiatives depended on US collaboration with Andean governments, but also on US government and business coordination. The largest obstacle the BEW confronted was the failure of American firms to supply the adequate quantity of legal substitute drugs or “acceptable equivalents.” As the US Embassy in Bolivia reported, “The general lack of interest in the Bolivian market which is being shown by American exporters of drugs and pharmaceutical supplies is encouraging continued purchase of German products of this nature.” The embassy repeatedly observed that the efforts of Bolivian importers to do business with US firms were thwarted by American pharmaceutical houses “not interested in the Bolivian market.”108 And the lack of American drug replacements undermined US efforts to exert pressure on Andean governments to comply with economic warfare initiatives: “As the [State] Department is aware the Embassy has been promising local merchants an acceptable product to replace German drugs for some time and the Embassy’s failure to do so is becoming increasingly embarrassing as the available supply of German drugs dwindle.”109

To deal with this problem, the embassy called for government intervention and asked the State Department to put pressure on US drug companies to distribute their products as a wartime imperative.110 The government’s outline for overcoming the drug replacement problem seemed to be a combination of a business plan and a national security directive:

1.That American pharmaceutical firms be induced as a patriotic duty to enter the Bolivian market.

2.That American firms already having representatives in Bolivia change to representatives who will push their products.

3.That the Board of Economic Warfare, War Production Board, and War Shipping Administration be shown the critical importance of American pharmaceutical products to the economy of Bolivia and to the economic warfare of the United States, so that provision may be made for shipments of these commodities.111

Behind such economic appeals to “patriotic duty” lay the coercive capacity of the state. Just before the formal US declaration of war, the State Department had issued its “Instructions of September 20, 1941,” amended on December 13, 1941 after Pearl Harbor, that set out a standard of conduct for US firms that instructed them to stop doing business with Proclaimed List firms and warned them that “strict compliance with such standard was required.” The BEW mission brought these “Instructions” with them to the Andes and gave them to US embassies for distribution to “All American concerns.” The State Department asked to be kept informed of US companies not cooperating with economic warfare policy, explaining the government was in a “position to exercise a number of sanctions against any American concerns not cooperating.”112

The US government could force US businesses to comply with economic warfare initiatives; however, there was in fact a considerable degree of collaboration between the government and the private sector in implementing the pharmaceutical replacement program in the Andes. This collaboration came in a number of forms. The US government worked with other governments and industry players in the Andes and the United States to compile lists detailing national medicinal needs, current drug stocks, and competitors’ products and delivered this “commercial intelligence” to American pharmaceutical companies.113 To improve US drug distribution networks, for instance, the government distributed to US manufacturers a list of “firms, organizations, and individuals,” including government offices, the Pan-American Sanitary Bureau, and the Peruvian military, that were “interested in importing drugs and pharmaceuticals from the United States.”114 When US firms refused to work with distributors who also handled competitors’ products, the embassy tried to get more local distributors to enter the market (in striking contrast to the comparable refusal to diversify drug importers on the US end).115 Fostering business relations between American and Andean firms was paired with coordination among agencies of the US government. The BEW and the State Department together tracked reductions in German drug sales and kept US companies abreast of increased demand. Government agencies also expedited licensing and drug shipments to tackle the replacement problem.

American companies also coordinated with one another to advance US economic warfare initiatives. In Bolivia, one of the oldest US merchant businesses in South America, WR Grace, offered to transport Parke, Davis & Company drug products to parts of the country where they traveled for their own business. As WR Grace representatives explained, they were “happy to haul” pharmaceuticals “if such would aid the replacement program.”116 Pharmaceutical companies also worked to expand drug sales by cultivating ties with local physicians. Parke, Davis & Co., for instance, hired a “resident representative . . . [for the] sole purpose of acquainting the medical profession with Parke, Davis products,” and the US Embassy prodded other US pharmaceutical houses to do the same: “American manufacturers of ethicals will be encouraged to compile and distribute such compendiums . . . [in] Bolivia and other Latin American countries.”117

These public programs and policies were paired with more covert levels of collaboration between business and government officials. The United States gathered intelligence through business contacts acting as undercover agents across Latin America. Even before the United States officially entered the war, US businessmen had access to extensive market information that they shared with the government.118 For example, in 1940, responding to a request from the Federal Bureau of Narcotics, Maywood provided information about the state of the coca industry in Peru, including statistics on quantities of cocaine exported as well as a list of cocaine manufacturers in the country.119 After the BEW’s initiative began, these business intelligence networks were more aggressively used. As an expression of his “loyalty to this country,” Maywood’s Peruvian supplier began providing the company with information on businessmen in the region, and Maywood in turn passed the information on to the US government to facilitate the implementation of the Proclaimed List.120 The government actively coordinated these covert intelligence-gathering efforts, as recommendations made by the Board of Economic Warfare made clear: “To handle the job effectively for the whole country, however, at least two experienced Spanish-speaking American business-men should be employed for field investigation. It is suggested that these men ostensibly retain their private positions as representatives of American business so that their moving about the country unobtrusively will be facilitated.”

These “undercover agents” were only one part of a much larger “corps of unofficial observers” culled from “friendly firms” who monitored Proclaimed List matters for the US government.121 All of these sites of public and private collaborations ultimately placed the US government and pharmaceutical industry in a decisive position to capitalize on the drug trade and the regulatory principles and powers that traveled with it in the war’s aftermath.

SCENE SET FOR DRUG CONTROL

The experience on the ground in Peru and Bolivia during the war served as a laboratory for US-promoted drug control policies around the world. By the end of the war, the economic warfare policies had effectively squeezed German-manufactured pharmaceuticals out of the Andean market, replacing them with the more “desirable” US-manufactured equivalents. In Peru, economic warfare policies not only helped US corporations triumph over German business in the realm of pharmaceuticals, but even before the end of the war the United States “ranked in the first place as a supplier of merchandise” and was “by far the principal source of Peruvian imports,” while also being the most lucrative export market for Peruvian raw materials.122 US pharmaceutical companies gained knowledge and access to the Andean market and acquired a preferential trade status for US “pharmaceutical specialties.”123 Bolivia similarly emerged from the war increasingly dependent on exports to the United States, particularly as the price of tin began to drop and Southeast Asian sources of supply returned to the market. Glenn Dorn has described the testy negotiations between the State Department, the Foreign Economic Administration, large mining companies, and the Bolivian government over a new tin contract, where the desire to maintain labor protections was counterbalanced by the power of large mining companies, the sinking price industrial countries were willing to pay, and the vulnerable negotiating position of the Bolivian government (which would subsequently fall in a coup) ever dependent on tin revenues.124