CHAPTER 3

Raw Materialism

Exporting Drug Control to the Andes1

The unequal position in which nations found themselves with regard to access and participation in the international drug trade in the aftermath of World War II depended on more than the promotion of an ideology and economic model to advance and justify US global preeminence. It entailed the rigorous design and enforcement of an international policing apparatus. The US government sought to ensure the access of pharmaceutical manufacturers to the raw materials flowing from the global South into US pharmaceutical laboratories, and to promote the consumption and reexport of US mass-produced drugs. This required a concerted effort to implement an effective international drug control regime, including an often contested determination to revise laws and cultural practices in those nations where valuable drug agricultural crops were cultivated. While over the subsequent decades marijuana and an array of synthetic drugs came under the purview of drug control officials, initially the two primary raw materials targeted by regulators included the poppy plant and the coca leaf, used for manufacturing opiates, cocaine, and Coca-Cola. The production of opium involved an international network of economic, military, and political interests invested in a commodity chain spreading raw material from Southeast Asia and the Middle East into Europe and the United States (where it was transformed into pharmaceutical painkillers). The coca commodity chain, on the other hand, was more exclusively situated within a US imperial domain due to the fact that the principal geographic location of coca leaf cultivation was the Andes Mountain slopes of South America; a part of the hemisphere that US interventionists have long enjoyed proprietarily depicting as “America’s backyard.” Looking at postwar efforts to police the international coca trade offers a unique window onto the workings of US power through its considerable influence in shaping the principles governing international drug control. Advocates of drug control, led by US officials, focused their attention on limiting the cultivation of drug crops according to parameters established by the combined interests of the pharmaceutical industry and US national ambition.

Efforts to police the international drug trade were not new, but the novel balance of power in the postwar world, characterized by the US’s unprecedented position of global dominance, ensured that international drug control took on a new character. The determined effort to regulate the international flow of drug commodities was a twentieth-century invention. It was a structure that had been modeled on US domestic policy and it sought to establish regulatory oversight through a system of licensing and taxation to monitor the international trade. Until mid-century, global participation and reporting was haphazard and the drug control regime had relatively limited authority. By the onset of World War II, only in the early stages of implementation, international efforts to maintain the drug control apparatus effectively went into hibernation. At war’s end, the drug control functions that had previously fallen under the authority of the League of Nations were transferred to the United Nations, which established the Commission on Narcotic Drugs (CND) to oversee its implementation. The internationally renowned Harry J. Anslinger, the commissioner of the US Federal Bureau of Narcotics who had played a pivotal role in mobilizing and organizing the international drug trade to advance US interests in both war and peacetime, immediately assumed an influential position on the newly constituted CND as the official US delegate to that body. Anslinger’s impact on the CND’s work cannot be overstated, as he was the most prominent advocate for drug control of the most powerful nation working to steer the new commission’s agenda toward US priorities. As World War II transitioned into the Cold War, and with US officials exerting a disproportionate influence on international drug control, pressure grew for Andean countries, especially Peru and Bolivia, to limit coca leaf cultivation according to definitions of legality and illegality being established by powerful interests invested in the drug trade.2

The United States and the United Nations were the main architects of the drug control regime that sought to eliminate all production of coca in excess of those leaves grown and processed for what international drug conventions of 1925 and 1931 had designated as “legitimate needs.”3 The conventions defined “legitimate needs” narrowly to include exclusively those leaves destined for “medical and scientific” purposes. US national narcotics law since its inception in the 1914 Harrison Narcotics Act included an additional “legitimate” allowance that Anslinger successfully lobbied for inclusion in international regulations: “special coca leaves” destined for use in the manufacture of a “nonnarcotic flavoring extract”; in other words, for the manufacturing of Coca-Cola (illustrating the already formidable influence on the tenets of international drug control by US private companies and the state). Under the drug control system, first coordinated through the League of Nations, signatory countries submitted annual estimates of their “legitimate need” for narcotics to a board that monitored the trade by overseeing a system of nationally administered import and export certificates. Governments were responsible for granting authorizations to importers and exporters as a way of monitoring the volume of trade to prevent domestic stocks of controlled substances from exceeding a given country’s annual estimates. There had been a long history of US unilateral efforts to gain South American compliance with US priorities for the flow of coca commodities, relying particularly on what historian Paul Gootenberg refers to as “coca diplomacy,” whereby private corporations with investments in the trade manipulated purchases in collusion with the FBN’s efforts to pressure countries like Peru to “adopt US-style drug policies.”4 After the war, these private and national efforts became institutionalized internationally in the policies and priorities pursued by the CND.

THE TURN TO COCA LEAF LIMITATION

Of the various problems facing the Commission in regard to the control of the international traffic in narcotic drugs, that of limiting the production of raw materials needed for the manufacture of such drugs is the most urgent and important.

—UN Commission on Narcotic Drugs, 27 January 19475

At the CND’s very first session a reinvigorated focus on international trade was paired with “the most urgent and important” effort to limit and control a particular sector of the drug commodity chain: the production of raw materials. In practice this meant targeting the production of raw materials in the Southern Hemisphere: securing the access of European and American manufacturing countries to these raw materials while locking developing countries into the bottom rungs of global economic production. And to this end, one of the first major initiatives pursued by the United Nations was a push to control the production of the coca leaf—the one of two primary categories of narcotics (the other being opium) that resided firmly within a US sphere of influence. By July 1947, as part of the preparatory work for a conference to deal with “the possibility of limiting and controlling cultivation and harvesting of the coca leaf,” the CND noted that while the international trade in coca leaves fell under earlier drug control treaties, “the existing conventions did not attempt to limit the cultivation and harvesting of coca leaves in producing countries.” To that end, restricting coca cropping in the Andes to that destined for export became one of the first major projects launched by the CND.6 The official reliance by drug control advocates on a legal framework of limiting the international drug trade according to regulators’ definition of “legitimate needs” entailed recasting the largest legal market for coca leaves in the world as undesirable and illegal, namely the indigenous consumer market for the plant in the region where it originated.

In 1947 the world supply of coca leaves grew primarily on the Andean cordillera in Peru and Bolivia. Of those leaves not consumed locally, coca from the Andes was exported primarily to manufacturers in the United States, ensuring that any effort to limit and control the international coca commodity circuit was fundamentally structured by power inequities within and between nation-states of the Western Hemisphere.7 As described in the previous chapter, the United States refashioned itself in the name of Cold War national security as the primary supplier of global “resources for freedom,” and controlling the flow of raw materials into North American stockpiles became a policy priority. In the pursuit of this objective US government officials recognized that the new global order augured new roles to be played by institutions of international governance. In the drug field, US leadership guided priorities as the United Nations became a vehicle for assessing and then controlling the scale, scope, and context of “legitimate” distribution of the coca commodities (which included coca leaf, crude cocaine, cocaine hydrochloride, and coca flavoring extracts). The US unilateral drug control initiatives during the war, which linked control over the drug economy to the military, public health, and political priorities of wartime national security, found a prominent place in a Cold War expansionist vision. A concerted effort, both unilateral and through multinational forums like the United Nations, to extend the reach of narcotics control into countries that supplied the raw material imports for pharmaceutical manufacturing and national stockpiling became a key aspect of the system.

The United Nations may have been viewed by some as a forum for moderating US power—as a place for both weak and powerful countries to assert national interests within a new, rapidly evolving, international order. It was nevertheless structured by the convergence of US capitalism and the colonial legacy of Great Power diplomacy. The CND’s attempts to delineate a “legal” coca leaf market by limiting production to selectively defined “legitimate needs” was part of a North–South global dialectic whereby the industrial powers continued to lay claim to the natural resources of the “developing” world, often by means of direct social, economic, and political intervention. The United States independently and through its influence at the United Nations sought to define the “legitimate” market for a natural resource, coca leaves, as exclusively one premised on the leaves being characterized as “raw material” for the manufacturing of other things. This entailed delegitimizing the widespread consumption of coca in its natural state, whether chewed, steeped as maté, or put to other cultural, spiritual, and ritual uses for which the plant was valued among indigenous communities in the Andes. In the process, the United Nations became a mechanism for pursuing US national security policy by extending the international policing of drug flows beyond national borders and into the domestic sphere of countries where coca leaves were grown.8 Coca leaves and cocaine were not illegal themselves; they—and other substances that came to be regulated and culturally characterized as “dangerous drugs”—straddled the licit/illicit divide, their legal status being dependent on their circulation within the marketplace, that is, on who grew, manufactured, sold, and consumed them. As the multinational reach of the US pharmaceutical industry grew, so too did the international reach of a renewed drug control regime to police participation within it.

The geographic home of coca leaf cultivation, the semitropical slopes of the Andes Mountains, grounded the international routes through which coca-derived commodities flowed. While exact statistics are not available, the vast majority of coca leaves grown in Peru and Bolivia were cultivated for domestic consumption, where the leaf was particularly valued by the Aymara and Quechua communities. In 1946 the United Nations estimated that at minimum 17.5 million pounds of coca were cultivated in Peru and an additional 11 million pounds in Bolivia. This only accounted for coca that was taxed by the respective governments, vastly underestimating the actual amount grown since much coca grown domestically was not tracked or taxed. Of this low-estimated 28.5 million pounds of coca leaves cultivated in the Andes that year, only roughly 4 percent was destined for export to manufacturing countries (all from Peru).9 The bulk of coca grown in Bolivia was consumed domestically or exported regionally, primarily to northern Argentina and to a lesser extent Chile (along with Bolivian agricultural workers).10 With the drug control regime now targeting “raw materials” and, in particular, seeking to eliminate the market for all coca that was not being exported to the North American market, Bolivia’s position as a producer exclusively for a domestic and regional market of largely coca leaf chewers meant its international leverage was negligible. This was in contrast to Peru, which was the primary cultivator of coca leaf for the international market constructed to meet North American and European demand for coca-infused beverages and pharmaceutical-grade cocaine since the turn of the twentieth century. Chewing and consuming the coca leaf in its raw state were practices limited to the Andes. Once exported from the region, industrial chemical manufacturers invariably transformed coca leaves when they used them as building blocks for other commodities, most notably Coca-Cola and cocaine hydrochloride.11 Setting aside the regional economy for the moment, the vast majority of coca leaves exported from Peru were imported by manufacturers in the United States.

The United States was the destination for 85 percent of Peru’s coca leaves export market in 1946.12 The United States dominated this market not only because of regional ties but also more importantly because of US narcotics law, which fell under the jurisdiction of the Treasury Department and operated through the taxation of trade. Coca, as a legally designated “narcotic,” could only be imported in its raw material state; all finished controlled substances in circulation within the country (or for export) had to be manufactured within the United States. Peru did manufacture small quantities of refined and crude cocaine for export to Europe; however, Peruvian-manufactured cocaine was barred from entry into the dominant US market. The Jones-Miller Narcotics Import Act of 1922 entrenched this system, banning all cocaine imports into the country. Thus national law within the United States already ensured that South American countries could only be suppliers of the raw material (coca leaves) to the largest world manufacturer of coca-derived commodities, despite failed efforts before and during World War II by Peruvian government and businessmen to challenge these limitations.13

The pharmaceutical manufacturers Merck & Co., Inc. and Maywood Chemical Works held exclusive government-issued licenses to import coca leaves. Merck imported the leaves for the purpose of manufacturing cocaine hydrochloride to be used by the pharmaceutical industry as a local anesthetic and for research. Maywood extracted cocaine from the coca leaves in the process of manufacturing a “nonnarcotic flavoring extract,” otherwise known as “Merchandise #5,” a component of the famous soft drink Coca-Cola.14 While today the illegal cocaine market’s scale dwarfs quantities produced for the pharmaceutical industry, in the postwar period the reverse was true. The legal industry’s production vastly exceeded quantities of illegal drugs seized, while all drug production appeared minuscule beside the quantities of cocaine destroyed or sold to the pharmaceutical industry as a by-product of processing the coca leaves as a flavoring extract for Coca-Cola. As early as 1931, even before Coca-Cola’s international operations expanded during and after World War II, Coca-Cola was using more than 200,000 pounds of coca leaves annually to manufacture some 10,000 gallons of “nonnarcotic flavoring extract.”15 As laboratories worked their magic, these internationally derived commodities were repackaged and sold as “national” American products, celebrated even as embodiments of the medical and entrepreneurial benefits of US capitalism.

The policing of South American coca cultivation worked in tandem with securing raw materials for manufacturing “American” drug products. The North–South hierarchy of national participation within the international coca economy—South America as the producers of raw materials, the United States as the producer of manufactured goods—filtered through power disparities within Peru and Bolivia. This was abundantly clear in the first postwar effort to limit Andean coca cultivation to those leaves destined for export that unfolded under the auspices of the specially convened UN Commission of Enquiry on the Coca Leaf. The CND sent a group of international delegates, chaired by the United States, on a fact-finding mission to the Andes in 1949 to investigate the “problem” of the coca leaf. The UN mission sought to study and ultimately control the Andean landscape of coca leaf production and consumption and in the process was intervening in local conflicts over the terms of national economic development, political participation, labor and land rights, and in particular, the place of the “Indian” in modern society.

Efforts to control and limit the coca trade exposed and in part depended on political, racial, and economic hierarchies in the Andes. In 1946, coca represented 90 percent of the revenue for La Paz’s Excise Office, and though of lesser significance in the more diversified Peruvian economy, the coca market was also formidable there.16 In both Peru and Bolivia the majority of coca was grown by small peasant farmers, the majority of consumers were indigenous communities in both agricultural and mining regions, and a politically powerful landowning elite dominated the export market.17 The UN investigators themselves struggled to comprehend the complex internal dynamics in both countries, although their goal of regulating the international market entailed collaborating primarily with a local “white” oligarchy. The UN study focused on the supposed nefarious practice of Indian coca leaf consumption: “No study can be made of the sections of the population in Peru and Bolivia which chew the coca leaf without specific reference to the various groups constituting the populations of those countries. These groups are ordinarily designated ‘white’, mestizo, and ‘Indian’ . . . almost all coca-leaf chewers are ‘Indians’, though this does not mean that all Indians are coca-leaf chewers. Moreover, the term ‘Indian’ is not a sharply defined one. The distinction between ‘Indian’ and mestizo is normally based on cultural, social, economic, and linguistic considerations.”18

Careful to recognize the cultural specificity of racial and ethnic designations, the United Nations nevertheless oriented their drug control initiatives toward the study of “Indian” culture through social scientific method. In the topics covered by investigators, including whole sections of their final report devoted to “geographical considerations,” “medical considerations,” “methods of consumption,” “race degeneration,” “effects of chewing,” “medico-biological research,” “coca-leaf chewing as a characteristic of the Indian’s life,” “the legal regulation of labor,” and the “economic value of coca-leaf production,” there was not a single mention that the region was in the midst of experiencing one of the most profound challenges to the centuries-long subjugation, exploitation, and political disenfranchisement of the Andean Indian majority.

Both Peru and Bolivia had large Aymara and Quechua populations, although Bolivia’s indigenous majority was unique in the Americas. The United Nations estimated that about half of Peru’s eight million population was Indian, and of Bolivia’s population of four million more than 50 percent were Indian, 13 percent white, and the remainder mestizo.19 In both countries Indians were denied basic voting rights and political protections and were subject to onerous land tenancy and domestic servitude obligations to a small and powerful landholding oligarchy. As historian Laura Gotkowitz documents, indigenous struggles for land and justice in Bolivia that stretched back to at least the nineteenth century culminated in 1947 in a number of both urban and rural rebellions at the very moment UN drug regulators focused their attention on the region. These indigenous rebellions challenged a political and economic order that produced conditions of extreme subjugation, which many observers and peasant rebels readily decried as slavery.20 While similar mobilizations for rights would occur later in Peru, it is striking that no mention was made of these upheavals in Bolivia by the commission, especially considering investigators traveled through key regions that had experienced the most violence and turmoil as peasants and mine workers organized to challenge severe labor conditions and profound inequalities in land ownership, where 6 percent of the nation’s landowners controlled 92 percent of all developed land. It is not clear how coca and the effort to control it may or may not have figured in to these regional challenges to the status quo, but the characteristics of the assault against Indian coca consumption were definitely embedded in this larger political context. “Between 1944 and 1946, the region witnessed processes of democratization, radical labor movements, and the rise of the Left. This political opening closed down quickly with the shift to cold war containment.”21 The effort to extend drug control was just one component of the reaction against mobilizations for agrarian reform, political rights, and trade union power that oriented attention away from Indian economic grievances and political demands and toward social scientific assessments of presumed cultural practices in need of transformation. Drug control in the Andes began as the province of international “experts” and national economic elites who accrued the greatest profits from coca leaf processing and export. Indians, on the other hand, dominated the cultivation and consumer side of the national economy and as such became objects of study and control. A complicated landscape of cultural, social, and political struggle was reduced to factoring select human lives as national resources, and more particularly labor power, effectively rendering them the raw material for debate about regulating the coca market in the name of the public good. Ostensible medical concerns, “the harmful or harmless” effect on the “human body,” in particular the bodies of Andean Indians, were recast as questions for business management and control over commodity flows; that is, as questions tied to “production” and “distribution” of the coca leaf, to the presumed need to modernize and civilize a backward population, and to the policing of new definitions of legality.

The discursive terrain of the UN commission, and its US leadership, reframed an effort to impose an economic and political order as a social scientific “enquiry” that mapped easily onto the deeply embedded racial and class hierarchies which structured Andean society at mid-century. Warwick Anderson and other scholars of US colonialism in the early twentieth century have noted how a new science of public health easily lent itself to a broader effort to refashion the “bodies and social life” of colonized people in a “civilizing process,” which was “also an uneven and shallow process of Americanization.”22 After World War II, drug control in particular, and the discourse that traveled with it, similarly became a “scientific” tool for extending US power by targeting the minds and bodies of populations deemed “uncivilized,” and promoting an economic order premised on the supremacy of US capitalism, even while these efforts depended on local collaboration and an embrace of a technocratic discourse of social science and public health. It was undoubtedly more palatable for national elites to participate in international initiatives if the most economically vulnerable and politically repressed populations were identified as the site of the “social problem.” Still, the UN commission became a battleground among political and economic interests in Peru and Bolivia over the terms of national incorporation into international markets and systems of regulation. While a degree of lip service was paid to coca’s historic cultural importance in the Andes, where it had been chewed for at least two thousand years, the commission’s prime objective was to bring about its limitation and control. The international emphasis on raw materials as the necessary locus of this control meant that the UN initiative and the Andean response to it consisted of a debate about the coca leaf and, in particular, the land, life, labors, and consumption habits of Andean Indians. Deploying a language of well-being grounded in Western scientific explanations and tools—whether policing strategies, laboratory techniques, models of economic development, or medical assessments—experts in the field of international drug control sought to direct the flow of coca leaves within an international commodities circuit defined and oriented by US priorities.

THE UN COMMISSION OF ENQUIRY ON THE COCA LEAF

The UN commission published its findings and recommendations in 1950, disseminating only the first of many official UN investigations and publications into the matter. The report’s publication came at the end of three years of organizational effort, fieldwork, and a considerable amount of debate both within and outside of the commission, in the Andes, and in the United States. These debates, to which we now turn, together with the various organizational structures and ties which framed both the issues at hand and the necessary “expert” qualifications for participation, provide a critical perspective on the parameters of drug control within a US sphere of influence in the mid-twentieth century. They show how racial, class, and national hierarchies inflected the work of experts schooled in the arts of policing, medicine, business administration, and the social sciences, shaping both the framing of “problems” and the proffering of solutions. They show how economic concerns relating to the control over international commodity flows and, in particular, a US-dominated vision for hemispheric development and trade, ensured that certain capitalist assumptions underwrote the logic of the drug control apparatus as well as the social and cultural arguments that it partially inspired.

The disproportionate power of the United States within the hemisphere (and the globe) influenced the leverage of coca growing countries in seemingly international forums like the United Nations, where hemispheric drug control was largely mediated by US actors. Even in the early stages of international efforts to monitor the coca economy, US political and corporate interests exerted pressure for South American compliance. When the League of Nations was having difficulty obtaining statistical information on Peru’s coca economy, Maywood Chemical Works intervened by dangling the possibility of the elimination of Peru’s coca leaf export economy if the information was not forthcoming. In a reply from Peru, forwarded from Maywood to the State Department and on to the League of Nations Secretariat, Maywood’s supplier in Peru, Dr. Alfredo Pinillos, brought the matter to the attention of the Peruvian Minister of Foreign Affairs “in order to forestall the possibility that the exportation of coca leaves may be prohibited—which would be very unjust and unfair, and which would mean the death of one of the most important national industries.” This corporate diplomacy had effect. In response, the Peruvian Minister of Foreign Affairs promised national compliance with the system, issuing export certificates and designating specific ports for the coca leaf and cocaine traffic. While Peru agreed to comply with monitoring the international trade, it sought to preserve the domestic coca leaf economy as a strictly national concern. The foreign minister asserted: “Peru as producer of coca leaves and crude coca will not make any concessions to restrict the cultivation and the production of coca leaves, nor prohibit the use of it for its natives, as it is actually a national problem which is now being studied by the Peruvian government.”23

This early resistance to the supply-side control paradigm being promulgated by institutions of international drug control continued during the UN era, and US importers and manufacturers continued to exert a disproportionate influence. The impetus behind the CND’s initiative for controlling raw materials may in part have emerged from concerns of US importers with regard to maintaining their coca leaf supply. Merck & Co., Inc. wrote to FBN Commissioner Harry Anslinger in January 1948: “As you know, we have been having trouble in obtaining adequate supplies of Coca Leaves.” Anslinger, who also served as the US representative on the CND, rejected their suggestion of setting up new plantations, emphasizing the drug control imperative of preventing “any further coca leaf plantings.” Yet, he reassured them, “I believe that as soon as the United Nations Commission of Enquiry finishes with its study of the coca leaf chewing there will be a tremendous surplus, because the amounts chewed approximate twenty-five million pounds.”24 The head of the FBN confidently anticipated that the success of the UN commission’s efforts to eliminate Andean coca leaf consumption would produce surpluses for US importers. Anslinger explicitly saw this projected outcome as a necessary precondition for securing ample supplies of raw material for US manufacturers.

In the context of US pressure and international attention on the coca commodity chain, the immediate pretext for the UN commission’s creation and fieldwork emerged in an official petition from the Andes. Andean businessmen, government officials, and scientists collaborated with the drug control apparatus at mid-century. They were motivated by the economic and political advantages of aligning with the United States, as well as by an interest in retaining a degree of control over national economic development and political power.25 Responding both to an increasingly acrimonious debate among Peruvian scientists as to the relative merits or dangers of customary Indian coca leaf chewing and to the growing international pressure for Peru to enforce and maintain stricter control over their domestic and international coca production and trade, in April 1947 the Peruvian government submitted a proposal that the United Nations conduct a field survey on the coca leaf. Given the prominence of US power in the coca commodity circuit and the CND’s inaugural interest in limiting the production of raw materials in producing countries, Peru approached the United Nations in an attempt to moderate the impact of the coca control apparatus that was already being implemented.26 In a challenge to what many Peruvians and Bolivians believed was the hasty classification of the coca leaf as a dangerous drug, the Peruvian representative Dr. Jorge A. Lazarte explained “his government’s reason for making the request,” noting the difficulty of handling the situation due to the scale of consumption, the fact that the coca shrub grew wild, and the “highly controversial” nature of the issue. He emphasized the need for further investigation:

At no time had the Government of Peru been able to carry out an organized enquiry into the physiological and pathological effects of this habit or to ascertaining whether it was necessary to suppress it. The habit had endured for many centuries and the Indian population which indulged in this practice appeared to be healthy and prosperous, capable of very hard work with little nourishment. Many observers had remarked upon their agreeable disposition and healthy condition. The Peruvian Government was therefore faced with the dilemma whether to suppress it or not.27

Peru’s representative argued coca leaf chewing was a “habit” whose negative mental and physical effects had yet to be determined, even while it had the proven power to sustain workers on little food. Bringing together elite paternalism and an interest in Indian labor-value, Lazarte suggested coca enhanced the “Indian population’s” capacity to perform “very hard work,” a factor perhaps militating against prohibition. In fact, scientific investigations into Indian pathology and physiology would provide a common ground for proponents in the debate who all saw Indian labor productivity as a measure of coca’s impact on societal health and prosperity, even if they drew different conclusions. The leadership of the UN CND endorsed the project while presuming coca leaf chewing’s detrimental impact necessitated a focus on policing. The chairman of the CND, Colonel C.H.L. Sharman, the Canadian representative and close friend of the US representative, FBN Commissioner Harry J. Anslinger, “suggested broadening the scope of the study” to include “the possibilities of limiting the production and controlling the distribution of coca leaves.”28 This latter point would in fact become the main objective of the UN commissioners dispatched to the Andes. Looking back on these efforts, the Secretary of the UN Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC) (and later director of the Narcotics Division), Mr. G.E. Yates, declared that contrary to the Peruvian representative’s initial request, the commission “was not really a technical assistance mission. It was a mission to persuade or encourage these Governments [of Peru and Bolivia] to change their policy by recognizing that the coca problem was a thing to be tackled, and gradually suppressed.”29

The Peruvian proposal emerged from the United Nations in modified form. The original framework of public health and labor concerns was reconfigured as an initiative to control the scale and scope of the coca leaf economy, and eliminate the Indian practice of coca leaf chewing. This transformation ensured that along with two medical experts, the CND would appoint “two persons having experience in the international administration and control of narcotic drugs; one of these two members should preferably be an economist.”30 The final composition of the commission reflected the dominant influence of US capitalism on drug control efforts at mid-century. In particular, it embodied the combined interests of the US government and pharmaceutical industry, as well as the international network of “experts” upon whom it relied for legitimization. The president of the UN commission, Howard Fonda, was a US pharmaceutical executive nominated for the task by the head of the FBN, Harry Anslinger. Among other related institutional roles, Fonda was acting director of the American Pharmaceutical Manufacturers’ Association, director of the National Vitamin Foundation, director of the First National Bank and Trust Company, and the vice president and director of the pharmaceutical house Burroughs Wellcome & Company. Fonda’s directorship embodied the confluence of US financial, pharmaceutical, and manufacturing interests that assumed the helm of UN drug control initiatives in the Andes.

The extensive correspondence between Fonda and FBN Commissioner Anslinger during the commission’s fieldwork in the Andes reveals the close relations between the pharmaceutical industry and the international policing apparatus, as well as the formidable US influence on the work of the United Nations. In a typical exchange, Anslinger wrote to Fonda imagining the UN mission to be a welcome respite from his labors as a pharmaceutical executive: “I am sure that you are having a very refreshing experience after your many years in the drug industry.” Fonda in turn kept Anslinger informed of the commission’s progress, describing how he dealt with internal divisions and obstacles that emerged during the trip, having “in no uncertain terms let them [the other members of the commission] know I was boss.” In another dispatch, Fonda praised the work of the commission, highlighting his own role with the cocky nationalism and self-assurance of the successful businessman he was: “If I had not put some good old American salesmanship into this job and spread the honey this gang would have had one hell of a time.”31 The “gang” included three other appointees to the commission: the director of the Narcotics Bureau of France, a US-trained Venezuelan doctor and pharmacologist, and a Hungarian physiologist with ties to the UN Nutrition Division. The commission’s work did not proceed without some debate and disagreement, but their approach and conclusions reflected the dominant US influence on the emerging drug control apparatus.

Following the Peruvian representative’s petition and the subsequent convening of the commission, the United Nations resolved to send delegates to Peru, as well as to “other countries concerned as may request such an enquiry.” Bolivia, the second largest cultivator of coca leaves in the Andes, was the only other country to participate in the UN field survey.32 Colombia, the one other acknowledged cultivator of coca—exclusively for a small domestic market (reporting some 400,000 pounds compared to the almost 30 million grown in Peru and Bolivia)—had already implemented decrees to abolish the practice, while regional consumption in Argentina, Chile, Brazil, Venezuela, and Ecuador depended on small-scale cultivation or importations from Bolivia and Peru. Bolivia had been wary of international drug control initiatives since ratifying a 1925 International Opium Convention to be administered by the League of Nations, with the explicit disclaimer that “Bolivia does not undertake to restrict home cultivation of coca or to prohibit the use of coca leaves by the native population.”33 When word of the planned UN commission reached Bolivia, the politically powerful organization of coca plantation owners in the Yungas, the Sociedad de Proprietarios de Yungas (SPY), suggested Bolivia participate to prevent the control apparatus from undermining their influence. Across the Andes small peasant farmers grew the majority of coca, yet landowning elites dominated the export market. The SPY sought to ensure “that Bolivian coca not be included in the catalog of narcotic drugs and that, consequently, no restrictions be established regarding its consumption, production and exportation.” The SPY’s interest in pursuing the industrialization of coca products led the Bolivian government to seek inclusion in the UN enquiry, mistakenly believing the UN work might lead to the elimination of coca from the list of internationally controlled substances, opening up a new international market for Bolivian-manufactured goods.34

The head of the UN Division of Narcotic Drugs (which oversaw the CND), Leon Steinig, an American citizen of Austrian birth, revealed a different perspective when he appraised the Andean export economy in light of the pending field survey, indicating an apparent unwillingness to take Bolivia’s vision for industrial development seriously. “Bolivia,” Steinig declared, “was the only country exporting large amounts to other countries for consumption by addicts . . . all of the [coca] exported by Bolivia had gone to countries where the habit of chewing coca leaves prevailed.” Peru, on the other hand, was more favorably assessed, inasmuch as “half of the total [coca exported] went to the cocaine manufacturing countries and most of the remainder to countries manufacturing non-narcotic substances.”35 Thus in a context where international efforts sought to limit both Peru and Bolivia’s participation within the international coca commodity circuit to the production of raw materials for export to manufacturers (primarily in the United States), Bolivia as a producer only of “addiction” did not figure into the “legitimate” export vision of the UN commission at all.

The Bolivian government responded by accepting the technical assistance they believed would accompany the enquiry, while echoing Peru’s invocation of health and labor concerns: “Coca leaf chewing is not a vice in Bolivia, and no biological defects have been observed amongst chewers. . . . The loss of the coca plant would create a real problem in Bolivia . . . since it is an indispensable element in the subsistence of the agricultural and mine workers.”36

Reaffirming these concerns, the Peruvian delegate before the United Nations questioned the tendency to equate coca leaves with cocaine, an assimilation that produced the designation of Indians as “addicts” by “stress[ing] the fact that most of the research had been done on the harmful effects of cocaine and very little was known of the effects of chewing coca leaves.”37 National elites may well have been wary of attacking indigenous cultural practices at a time when exploited agricultural and mine workers were mobilizing for greater rights and in the process contributing to political instability; however, they couched their appeals to the United Nations in more moderate terms. Peruvian and Bolivian government officials contested the terms of their incorporation into the drug control regime by challenging whether coca should be regulated as a “vice” and instead emphasized both its potential to fuel national industrialization and its ongoing role in sustaining labor productivity in the fields and the mines. Debates about the harmful effects of the leaf, its role in local and international economies, and the quantities and dangers attributed to the ingestion of the cocaine alkaloid swirled around the commission and became central to the investigators’ work. The UN Commission of Enquiry on the Coca Leaf became a battleground for national elites over the terms of incorporation into international economic and control networks. Both Peru and Bolivia argued before the United Nations that coca might propel national economic development and modernization and claimed further study was needed. These debates unfolded for more than two years before, in 1949, the UN Commission of Enquiry on the Coca Leaf traveled through Peru and Bolivia, visiting regions tied to the cultivation, distribution, and consumption of the coca leaf.

FIRST STEPS: CONTROLLING COCAINE

The impact of the UN initiative—and the drug control framework it grew out of and extended—was felt even before the commissioners journeyed through the Andes and compiled their report. A division of labor was built into the hemispheric policing apparatus. The work of UN experts and scientists on the coca leaf “problem” unfolded in tandem with international police collaboration designed to “suppress” and “tackle” cocaine. Cocaine as a commodity—whose dangers, by the 1940s, were less disputed than those of the coca leaf—was quickly regulated in the Andes through the collaboration of Peruvian and US authorities, even while representatives continued to debate the appropriate mechanisms for dealing with the raw material, the coca leaf, on the floor of the United Nations.

By the time the UN commissioners arrived for their expedition in September 1949, the new president of the military junta in Peru, General Manuel A. Odría, had already invoked the work of the commission and the international demand for drug control to justify and explain a number of Supreme Decrees issued earlier that year. These decrees defined the illicit market specifically as the unregistered traffic in “cocaine” and introduced a paradigmatic shift in state-run drug control policy away from a question of public health and toward a new punitive approach centered on aggressive policing and market regulation. Defining and policing the “illicit” was facilitated by the establishment of a national coca monopoly to control “the sowing, cultivation, and drying of coca, its distribution, consumption and exportation,” and to limit coca’s industrialization, its processing for medicinal purposes, to the government.38

The United States publicly and enthusiastically welcomed these initiatives. FBN Commissioner Anslinger publicly praised Odría’s efforts in Time magazine. Collaboration between the FBN and the Peruvian police had in fact led to a much-publicized cocaine trafficking bust, which along with the pending UN “enquiry,” was used as public justification for the new harsher legislation introduced by the Peruvian government.39 Not mentioning the FBN’s involvement (perhaps so as not to inflame political currents opposed to US imperialism), the military government nevertheless situated these initiatives within an international context.40 El Comercio, a popular Lima newspaper and media outlet for General Odría’s government and the Lima social elite, reported that these decrees were passed because of the government’s “desire to extirpate drug addiction from the country and avoid the trafficking of cocaine by unscrupulous individuals, Peruvians and foreigners, that have assaulted the national prestige.”41

While previously Peruvian officials had invoked national sovereignty to challenge international efforts to control the domestic coca leaf economy, now Odría invoked the nation’s modernization and international prestige to justify consolidation of control over the domestic economy and the deeper integration of this economy into the international drug control apparatus. By instituting these decrees and taking aggressive action against “unscrupulous individuals,” Odría was capitalizing on international calls for drug control to garner domestic and foreign support for the new military regime. It also reflected one direct consequence of the UN- and US-inspired heightened policing of cocaine: the “birth of the narcos” whereby a “wholly new class of cocaine trafficker” appeared on the international scene after 1947, connected to a Peruvian cocaine industry that until that point in time had been legal.42 As the Peruvian economy and social control apparatus were further integrated into a US-dominated hemispheric order, the line delineating licit and illicit markets became a powerful economic and political tool, which relied on the demonization of cocaine and “cocaine traffickers,” even while securing supplies of coca leaves for export to US pharmaceutical manufacturers of cocaine.43

Political power accrued to those who embraced the drug regulatory regime. The military coup that brought Odría to power in October 1948 ousted José Luis Bustamente Rivera, who had come to the support of the nationalist (anti-imperialist), populist, though explicitly not communist, party Alianza Popular Revolucionaria Americana (APRA). When divisions between Bustamente’s government and Aprista dissidents resulted in a naval mutiny in the Lima port of Callao, the military intervened and installed Odría as Peru’s new president, foreclosing the possibility of an official political turn leftward. When the founder and leader of APRA, Victór Raúl Haya de la Torre, sought political asylum in the Colombian Embassy, General Odría argued the request should be denied on the grounds that he was a common criminal rather than political refugee, prompting a case that dragged on for years before the International Court of Justice. He based this charge on information gathered from his collaborations with the FBN in relation to the recent bust of a cocaine trafficker with Peruvian connections in New York.44 “Cocaine” then, as now, was a fungible commodity. For Odría, the battle against a “cocaine trafficker” (and founder of the socialist APRA party) consolidated his domestic power while augmenting his international political capital with the United States.45 Odría perhaps learned this not uncommon McCarthy-era tactic from FBN Commissioner Anslinger himself, who regularly invoked the spectacle of the “communist dope-pusher” to advance his agenda.46 More than simply currency in a play for US support, Odría traded in drug scandal domestically. The frequent spectacle of cocaine trafficking busts reported in the Peruvian media helped to criminalize domestic political dissent while giving legitimacy to the coercive measures the military junta was using to consolidate its control.47 The political manipulation of criminal enforcement was becoming an increasingly common tactic in the Andes (and throughout the world) as the drug control regime gained traction. It is worth noting that in the early 1960s Bolivian labor leader and Vice President Juan Lechín would be forced into quasi-exile, based on, as historian Kenneth Lehman has argued, “trumped-up charges of cocaine trafficking.”48

The spectacle of the drug bust was deployed as a political and economic weapon by the Peruvian government as it selectively licensed cocaine manufacturers and pursued criminal investigations to prevent seepage into the newly “illicit” realm. Government legislation and a series of spectacular media reports on criminal cases in the spring of 1949 helped delineate the line between licit and illicit cocaine, throwing former legitimate manufacturers onto the wrong side of the law. In one such incident, El Comercio published the mugshots of fourteen men, finely attired in business suits, accused of the crime of cocaine trafficking. The cocaine had been manufactured at the factory of Andrés Avelino Soberón in Huánuco. Soberón, a licensed manufacturer, was accused of producing cocaine in excess of his government contracts.49 The chief of police publicly attacked the “traffickers” for their luxurious lifestyles and their “ill-gotten wealth,” airing a populist appeal to the masses as the new regime sought to legitimate its rule.50 As the government consolidated its control, enforcing the new legislation, it literally created the illicit economy and numerous pharmacists, formerly legitimate manufacturers of cocaine, became embroiled in the “illicit” trade. This gave the government the power both to determine who could participate in the legitimate coca-commodities trade and to wield a powerful symbolic weapon attacking “criminality” in the struggle to consolidate political and economic control.

While the Peruvian military junta joined US efforts to designate and then crack down on the illicit traffic in cocaine, it sought to reserve a realm of legitimate production by invoking national heritage in defense of the coca leaf. The government declared it was the state’s duty to “defend the national heritage, represented by investments in the cultivation of this valuable plant whose application by scientific means produces great benefits for humanity.”51 In the decree that created the national coca monopoly, the government conceded the dangers that the chewing habit might have for the Indian population, while insisting that the taxation and industrialization of the raw material was of value to the national economy. Both Peru and Bolivia sought to hold on to their sovereign ability to utilize coca leaves as raw material for national economic, industrial, and scientific development, even if they were more ambivalent about protecting Aymara and Quechua consuming practices. In this regard, both governments acceded to the policing of the illicit cocaine economy, but limiting the raw material—the coca leaf—posed more obstacles for national elites. Despite these reservations, it became increasingly difficult for Peru and Bolivia to influence the terms of national participation within the international “legitimate” drug trade once the entire commodity chain was incorporated into the international drug control apparatus and economy.52 This was accomplished on the one hand through hemispheric police collaboration and on the other hand through UN mediation. With the intervention of the UN commission, efforts to restrict coca leaf cultivation to that destined for export into the “legitimate” cocaine (and Coca-Cola) trade relied almost exclusively on attempts to control Indian land, labor, and consumption while marginalizing the aspirations of Andean country elites to develop their own industrially produced coca-derived commodities for the world market.

UN INVESTIGATORS AND PERUVIAN SCIENTIFIC DEBATES

From September through November 1949 UN representatives of the Commission of Enquiry on the Coca Leaf traveled through Peru and Bolivia, visiting regions tied to the cultivation, distribution, and consumption of coca. It became clear only moments after the commissioners descended from their New York flight onto the tarmac at Lima’s airport that the commission’s primary objective, couched in a social scientific language of “development assistance,” was to convince the Peruvian and Bolivian governments to structure the Andean coca market according to their emergent principles of international drug control. Howard Fonda, the US pharmaceutical executive and head of the UN commission, announced to the assembled reporters that his goal was to study the negative impact of coca leaf chewing on the indigenous population and determine what needed to be done to eliminate it.53 The chairman’s explicit comments ignited a fire in the Peruvian press; reporters publicly questioned why the UN investigators were there if they already knew the answers to the questions they were purportedly arriving to study. The commission quickly distanced itself from these statements by issuing a press release claiming the UN emissaries held no preconceived opinions; they were there to pursue an objective scientific study of coca’s place in society.

The UN delegates’ subsequent three months of travel through Peru and Bolivia proceeded relatively smoothly, with the active assistance and cooperation of national government officials and their specially delegated liaisons—the Chief of Narcotics of the Peruvian government and a representative from the Bolivian Ministry of Public Health.54 The Peruvian and Bolivian governments both established special commissions to study the issue in conjunction with the UN commission’s work, and regional newspapers reported regularly on the progress of all parties. The commission’s final report, the Report of the Commission of Enquiry on the Coca Leaf, outlined its work methods and described how the delegates sought out contact with local civil authorities, military personnel, and with “the medical profession, pharmacists and academic circles . . . in all the localities visited.” In addition, “whenever possible the Commission endeavored to make contact with existing agricultural, industrial and other employers’ or workers organizations,” although it is not clear in trip documentation or the final report how successful these efforts were or what impact they had on the ultimate recommendations of the United Nations.55 It seems the UN commissioners did not solicit opinions from Indian coca leaf cultivators or consumers themselves—except, as described below, in the form of scientific research into the physiological effect of coca leaves on their bodies.

Due to the paucity of documentation, it is difficult to gauge popular reaction to the UN mission outside official circles. It is clear many communities were very concerned. When Bolivia’s Minister of Public Health and Hygiene welcomed the UN commissioners to the country, he was forced to address the widespread alarm that talk of coca eradication had already generated. He assured the public the commission’s investigation should proceed, “Without apprehension or nervousness among any social classes, [since] the object [of the commission‘s work] is to try to determine as final proof, if coca is a great tonic as it is considered to be among our indigenous masses, or a toxin that must be eliminated.”56 Debates among Peruvian scientists about the effects of coca on the Indian body and social development became a critical frame of reference for the UN commission, which drew upon a scientific discourse to pressure for an economically based system of limitations and controls.57 This focus was not merely an external imposition, but very much a product of local scientists’ incorporation into a US-dominated drug research network. These scientists depended on private and public capital to finance their research and to sustain political support for their work. Both Dr. Carlos Monge and Dr. Carlos Gutiérrez-Noriega, the two primary adversaries in the Peruvian debate, had studied and taught at US universities and maintained ties with various North American institutions.

Monge drew upon his work as the director of the Institute of Andean Biology to defend Indian coca consumption as a natural, harmless component of a high-altitude environment inhabited by the racially specific “Andean man.” This line of reasoning, grounded in the racial stratification of Andean society, relied on the idea that “the Andean man is a climactic-physiological variation of the human race”58 in order to challenge the notion that coca leaf chewing reflected pathological behavior. He leveled this argument as an Indigenista, paternalistically protecting the Indians from those who would disdain them as uncivilized or backwards. Nominated by the government to preside over the National Committee on Coca, an investigative body created in response to the UN initiative, Monge’s views carried considerable weight. Monge’s prominence in scientific and political circles in Peru both bolstered and was facilitated by his international connections. Interest and support for Monge’s Institute of Andean Biology came primarily from US-owned mining companies, the US Air Force, and livestock breeders of the central highlands, all of whom were interested in maximizing (worker/ soldier/animal) productivity at high altitudes.59 Thus, a nexus of national and international medical, military, and business interests facilitated the scientific research that became so central to debates about coca.

These institutional ties were facilitated by personal contacts. When the UN commission arrived in Lima, Monge was on tour in the United States, where he attended the Congress of Americanists organized by the American Anthropological Association and gave a presentation before the UN Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization on “Physiological Anthropology of the Inhabitants of the Altiplanos of America.” He returned to Peru in the midst of the UN visit to preside over the International Symposium on High Altitude Biology sponsored by Monge’s own institute, the Rockefeller Foundation, and the Carnegie Institution. The symposium was convened “to understand the new Andean biology and anthropology and the social and racial conduct of high-altitude man.”60 It attracted not only the UN commissioners themselves who participated in a number of the sessions, but also an array of prominent US officials, including the chief of US Air Force Medicine and the directors of the US Naval Medical Research Center and Army Chemical Center.61

Gutiérrez-Noriega, based at the Institute of Pharmacology and Therapeutics of the University of San Marcos, Lima, did his own tour of US scientific circles in 1949, lecturing at the Society of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics and at the University of Wisconsin.62 His work turned to coca as an explanation for what he viewed as the uncivilized state of Andean Indian society, arguing, for example, that the “influence of the drug through many generations may have some importance as a creative factor in psychological disturbances and racial degeneration.”63 Gutiérrez-Noriega’s work fundamentally influenced the UN commission’s report and was well received in the United States, even being translated for publication in the popular magazine Scientific Monthly. Introduced by the editors as the “first sustained study of [Indian coca use] in English,” Gutierrez-Noriega’s work asserted that coca leaf chewing was detrimental “drug” consumption: “In general, coca chewers present emotional dullness or apathy, indifference, lack of will power and low capacity for attention. They are mistrustful, shy, unsociable, and indecisive. In advanced stages many of them are vagabonds.” This narration began by representing coca leaf chewing as a social dysfunction and flowed easily into its presentation as a veritable reflection of criminal proclivity, making people not just “unsociable,” but “vagabonds.” Such arguments blurred the line between cultural practice and racially based notions of cultural, or even genetic, supremacy that increasingly were being articulated—in both the United States and the Andes—through the extension of a coercive penal apparatus.64

Although circulating in the same institutional networks and sharing a debate centered on Indian coca consumption, Monge and Gutiérrez-Noriega viewed each other as rivals, and indeed, their work approached the question of Indian coca leaf chewing from fundamentally different perspectives. Gutiérrez-Noriega attacked coca as generating Indian pathology whereas Monge saw it as a legitimate cultural practice of a unique—even super—human species. There was, however, considerable room for convergence between these two poles; both scientists relied on either debasing or idealizing the scientifically objectified “Indian.” Members of the Peruvian National Coca Commission headed by Monge praised Gutiérrez-Noriega’s work while emphasizing the need for more study. Dr. Fortunato Carranza suggested that research thus far had only produced “a state of confusion.” He also emphasized a point central to the national and international debate: the role of nutrition. While Monge defended coca chewing as a necessary and beneficial practice of Andean man, Gutierrez-Noriega saw it as fueling a vicious cycle of malnutrition. Carranza took a line somewhere in between, reflecting the spectrum of the debate—and the currency of racialized thought—in Peru. He acknowledged coca’s usefulness in dealing with the physiological effects of high altitude, yet claimed it numbed Indians to the hardships of life, robbing them of their initiative to improve themselves: “after chewing coca, one feels compensated for all the frustrations one’s had in life.”65

THE REPORT OF THE UN COMMISSION

In the wake of its consultations with local scientists, government officials, and business leaders the UN commission recommended that national governments implement policies for policing coca circuits not tied to the “legitimate” North American market, creating through legislative action what came to be called the “illicit drug trade”: a legal framework for controlling the circulation of both cocaine and coca leaves. The United Nations also recommended that Andean governments set about eradicating the widespread indigenous practice of chewing the coca leaf. Despite some resistance, the general tenets of drug control were accepted in the Andes (even though the effort to eliminate coca leaf chewing was never successful and remains practiced and defended by indigenous people to the present day). At mid-century the Bolivian government agreed with international drug control officials that scientific investigations into chewing coca leaves constituted the appropriate mechanism for resolving the issue. And in Peru, after establishing a national coca monopoly, the government hoped to “to limit, for now, and eradicate in the future, this general custom, in defense of the indigenous population.”66 The “defense” of indigenous peoples through the eradication of age-old cultural practices drew upon an Andean elite paternalism shared by UN regulators who explicitly defined coca’s hazards in terms of the racial and economic status of its consumers: “Not all Indians are coca-leaf chewers, though the great majority are. Moreover, chewing is practised among the mestizos, although to a much smaller extent. The very few whites who chew coca leaf must be regarded as isolated cases, and not as a social problem.”67

The UN’s report echoed Gutierrez-Noriega’s emphasis on coca’s alleged production of Indian degeneracy, decrying the negative implications this held for national economic development. The commissioners determined, among other things, that coca chewing maintains “a constant state of malnutrition”; it produces, in some cases, “undesirable changes of an intellectual and moral character” and “certainly hinders the chewer’s chances of obtaining a higher social standard.” The report emphasized that coca leaf consumption “reduces the economic yield of productive work, and therefore maintains a low economic standard of life,” before going on to recommend that Peru and Bolivia institute policies geared toward its eventual eradication.68

These conclusions directly responded to officials in Peru and Bolivia who defended coca consumption as being beneficial to national development. Defenders of the leaf argued that coca’s “vitamin content plays a part in the nutrition of the Indian,” suggesting the leaf was a valuable source of nutrition necessary to sustain Indian economic productivity.69 When the Bolivian government circulated a report backing up this claim, the head of the UN commission privately wrote to Anslinger dismissing the “Bull-ivian vitamin report.”70 Despite this scorn, tests conducted by the US Treasury Department for the commission seemed to verify the Bolivian position. In particular the Treasury Department found that the “vitamin content” within an estimated quantity of coca leaves consumed daily was “remarkably high,” with vitamins B1, C, and riboflavin figuring most prominently. Nevertheless, the commission’s report ultimately concluded: “In spite of this fact, it would by no means be advisable to supply these requirements by coca-leaf chewing because it must be emphasized that the toxicity of coca leaves (due to their cocaine content) would never allow a safe use as a nutrient.”71 It is hard to know if US Merck’s pioneering synthesis of vitamin B1 and its initiation of large-scale vitamin production in 1936 had any direct impact on this recommendation. But, the hegemonic framework of medical science—tied in large part to the production lines and projected consumer markets of major US pharmaceutical companies—obviously influenced the commission’s analysis in this regard.72

The push for limiting the indigenous coca market focused on stigmatizing Indian consumer habits and asserting coca’s negative physiological impact (due to its cocaine content). Arguments for coca eradication stigmatized Indians while proselytizing the need to help integrate them into a model of “civilization” modeled on liberal visions of land ownership and hard work.73 The UN report explained the “concept of individual ownership is constantly spreading among the native landowning population,” while lamenting that “[m]any Indians, however, possess no land, and work for others.”74 Drug control was presented as a tool for advancing a particular vision of societal progress. Drug control officials also had to contend with the fact that coca leaves were a linchpin in the domestic cash economy. Eighty percent of Bolivian tax revenues were “derived from coca,”75 and according to Gutiérrez-Noriega, the “coca leaf [was] the single most important item of commerce in the Andes.”76 The UN report supported these claims, finding that “except in some cattle markets, business is on a small scale and generally limited to the exchange of products between the Indians. An exception is coca leaf; it is, as a rule, paid for in cash. In such markets coca leaf is sold by the Indian who grows his own crop.”77 Coca eradication thus entailed the radical transformation of the domestic cash economy, including the elimination of many Indians’ primary medium of exchange, subsistence, and access to money, outside of the wage-labor sector. In an effort to accomplish this, a medical discourse of addiction accompanied a positivist narrative of economic development. The final report dismissed indigenous claims that “coca-leaf chewing dispels hunger, thirst, fatigue and sleepiness, or gives strength, courage or energy” as “superstition” and attributed this belief to “the Indian’s poor living conditions” and “his lack of education.”78

Controlling the consumption of coca was an integral part of the civilizing and nation building project the United Nations (and the United States) hoped to promote in the region, in an effort to control the export market and stabilize the region for foreign investment.79 As the commissioners neatly summed it up, “since there is an intimate bond between the individual and the community, it is also clear that the effects of coca-leaf chewing must be considered as socially and economically prejudicial to the nation.”80 Both in the press and before the CND, representatives of the Peruvian and Bolivian governments questioned the UN recommendations and the conclusions that led to them—nearly a year after the initial publication of the UN report and only one week after the Bolivian representative was provided with a Spanish translation of it.81 Unlike Peru and the United States, Bolivia did not have a representative on the CND and had to respond to the UN report as a guest in the chamber. These national power disparities before the United Nations mirrored the even greater disparities between those made subjects of investigation, the Indian mine workers and peasants whose bodies and lifestyles were the sites of contention in diagnosing the “problem” at hand, and the internationally dispersed medical, military, and political elite the commissioners consulted with and reported back to, during and after their tour. Both Peru and Bolivia, in good diplomatic form, praised the work of the commissioners but suggested that the research had been too hasty and that three months of fieldwork was insufficient to draw conclusions, arguing that more scientific research needed to be undertaken to determine whether or not the practice of coca leaf chewing was in fact harmful.82

Despite these apparently irreconcilable differences, however, there were in fact a number of shared assumptions and underlying concerns that seemed to animate all of the various participants. Officials sought to define the parameters of legitimate drug consumption while creating a logical framework for policing its boundaries. Scientific investigation seemed to represent the ultimate authority for determining policies relating to the control, distribution, and consumption of coca commodities. “Experts” in the fields of physiology, pharmacology, business management, policing, and medicine were the privileged participants in these debates. Those people most directly affected and concerned by the practice and the public and political response to it, Aymara and Quechua Indians, were excluded. This was forcefully apparent in a 1949 progress report from US Public Health Service scientists who were in the Andes studying coca chewing under the auspices of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). They constituted just one of an array of missions in South America at the time that collaborated with the United Nations and that together embodied the prominence of scientific investigators’ involvement in constructing visions for Latin American development—and in delineating the boundaries of legitimate participation in the coca market. This vision paired the valorization of scientific “objectivity” and “truth” while denying the possibility that the Indian point of view mattered. The NIH’s fieldwork at the Volcan Mines at Ticklio, Peru, involved analyzing blood and urine samples obtained from Indian workers to track cocaine absorption in the body. They noted their findings were ongoing and inconclusive, yet one thing was clear: “The statements in regard to the coca leaf habit given by the workers are not reliable.”83 This easy dismissal of the Indian perspective was also evident in the UN commissioners’ primary reliance on testimony provided by members of the Peruvian and Bolivian elite: government officials, military authorities, medical professionals, pharmacists, and academics. For the Andean elite and international regulators, the “Indian” embodied the hazards and promise of Andean economic development.

THE INDIAN QUESTION

This silencing of the Indian voice was in sharp contrast to the centrality of the Indian body as a primary object of investigation into the “problem of the coca leaf.” As drug control gained momentum, the physical and symbolic body of the Indian became central to the debate. Regulators studied the “Indian” in their attempt to convey the dangers of consuming the raw material coca leaf in its unprocessed form and implement a system of controls gearing all coca leaf production toward the export market. In this context “Indians” were both objects of science and policing and, increasingly, part of a North American popular imaginary about the Andes. Consequently in the effort to delineate new boundaries of legality, Gutiérrez-Noriega, the US public health scientists, and the investigators helping advance the work of the UN Coca Commission performed numerous tests aimed at exploring Indian bodies and minds.

Approaching Indians as almost natural components of the environment, researchers swooped down on mines, into the countryside, or even utilized the captive populations in penitentiaries and asylums, to study the absorption of cocaine alkaloids in the body—drawing blood, testing urine and excrement, and administering numerous IQ and other mental evaluative tests. An entire section of the commission’s report entitled “The Chewing of Coca Leaf” was devoted to analyzing what happens to an Indian body upon consumption of coca leaves. Investigators reframed the Indian cultural practice of chewing coca leaves as a process of cocaine ingestion that needed to be eliminated.84 This scientific faith in finding answers by probing into blood, stomachs, digestive tracks, and brains paralleled the easy objectification of Indians in popular literature, where Indians repeatedly were likened to animals, an eerie echo, perhaps, of the lab rats and dogs upon which Gutierrez-Noriega performed his first cocaine experiments. The provocatively entitled article “The Curse of Coca,” published in the Inter-American in 1946, exemplifies this contemporary mix of fascination and disdain for the Indian body in the context of criminalizing indigenous coca consumption in the name of drug control. A Swiss naturalist is cited describing a sixty-two-year-old man as walking “as fast as a mule could go, solely on coca,” and the coca fields “look too steep to climb, but barefooted men and women scramble up the steps like mountain goats.”85 An article in Natural History the following year described how coca leaves in the mouth “reminds one of a chipmunk with packed cheek pouches.”86 Objectification of the Indian body provided common ground for scientists, drug control officials, and a popular imagination that sustained policy initiatives of the time.

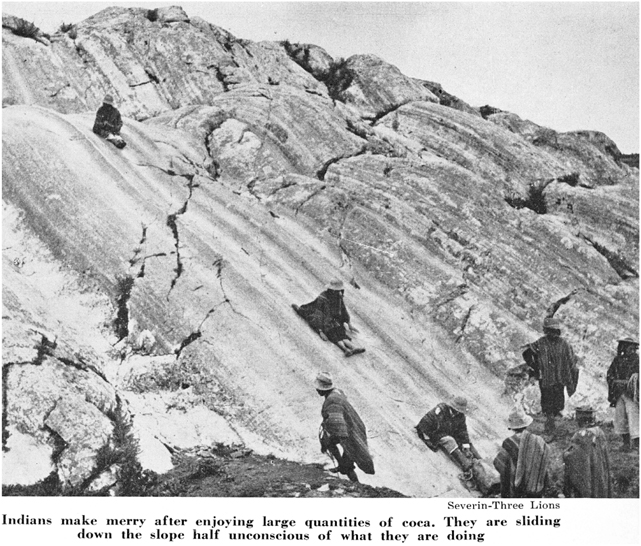

FIGURE 4. Photo and caption from a 1946 Inter-American article presenting coca leaf chewing as causing irrational behaviors by indigenous people.

The paired silencing of Indian voices and overproduction of Indian bodies in debates about coca provide a unique window onto contemporary ideas about national economic development and the selective policing of drugs. Discussions about coca drew upon long-standing ideological controversies over how best to integrate indigenous people on behalf of Latin American modernization and development. Linking coca chewing, “moral character,” and economic growth, drug control advocates drew upon a long colonial tradition of targeting Indians for cultural transformation, while providing a racially inflected social and economic rationale. At the second Inter-American Congress of Indian Affairs, held in Peru the same year as the UN commission’s visit, “the topic that raised more debate than any other related to the supposed physical degeneracy of the Indians,” an idea dismissed overwhelmingly by the attendees, although the question of the harmfulness of coca “was left undecided.”87 At the moment of this push for drug control, the notion of Indian racial degeneracy was becoming increasingly unpalatable. However, a new scientific language rooted in concepts like “addiction” supplanted more explicitly racialized debates, while re-embedding social, economic, and racial hierarchies through discourses of criminality and social dysfunction. The UN commission explained that it resisted the term racial degeneracy, which it linked to “the continuous outcry, heard all over Peru from the enemies of Coca chewing,” and rather suggested that their “analysis did not lead to the result that the Indian is degenerating; rather that mainly as a result of malnutrition, these valuable people addict themselves to coca chewing.”88

Finally, this recasting of the Indian problem, as a social rather than genetic issue, also was tied to US principles regarding hemispheric trade and economic development. The phrase “These valuable people” was as much an invocation of the commissioner’s “respect” for the Indians (as opposed to a caricatured Peruvian racial disdain), as it was an acknowledgment of Indians’ critical capacity as laborers and consumers within the postwar global economic order. Along with its other conclusions, the UN report argued that coca consumption “reduces the economic yield of productive work, and therefore maintains a low economic standard of life.”89 Drug control was presented as a means of overcoming economic backwardness. More specifically, the model of drug control advocated by the United States and United Nations tied the Andes into a hemispheric commodity chain in which coca leaves would ideally be grown exclusively for export (primarily to the United States). The Andes, then as the source of raw materials for North American manufacturers, ultimately might be further incorporated into a new international economic order as consumers of manufactured “American” goods. A member of the UN Secretariat overseeing the commission’s work articulated this larger economic vision when he suggested the fundamental issue underlying the investigators’ work had to do with the “main problem” of creating “a mass of consumers capable of supporting the new envisaged industrial and administrative developments.”90

MANUFACTURING CONSENT