CHAPTER 4

The Alchemy of Empire

Drugs and Development in the Americas

In July 1941, a United States Treasury officer checked out a pamphlet entitled “Coca: A Plant of the Andes” from the department’s library. Originally published in 1928 as part of the Pan-American Union’s “Commodities of Commerce Series,” the pamphlet described the coca leaf market with the intent of facilitating US international trade. In 1941, however, the government’s interest in the coca leaf had more to do with military applications than trade. The officer had gone to the library at the request of investigators in the US Army, and he returned the pamphlet to the librarian, having penned this lighthearted message: “I suppose the future will find each soldier chewing a wad of coca leaves as he repulses the attack of the invading hordes.”

The US Army was interested in exploring the stimulating properties of the coca leaf for potential use by its soldiers. In particular, the Treasury officer explained, “It seems that they have been discussing the stimulating effect produced by eating the leaves, as well as boiling them and drinking the tea.”1 Military researchers on all sides of the conflict during World War II sought to derive from plants or manufacture in laboratories an array of substances to heal, minimize pain from injury, and stimulate soldiers to make them more efficient fighters. Coca was just one of many such promising entities, although it seems that at least in leaf form it never gained a foothold in US military barracks.

The officer’s mirth over the humorous incongruity of coca-chewers filling the ranks of the world’s most powerful army was indicative of the growing cultural belief in the power of technology to transform raw materials (like coca leaves) into superior, and often more potent, products (like cocaine) and the presumed backwardness of older and simpler practices. This faith in “Man’s Synthetic Future” was on display at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) in a 1951 speech of that title delivered by the organization’s departing president: “Until half a century ago, medicinal products for treatment of disease were confined chiefly to plant or animal extracts or principles discovered originally through the cut-and-dry methods of the physicians of earlier ages. The chemist has now synthesized many of these principles and on the basis of this knowledge has been able to produce other products superior to the natural.”

This evolutionary vision portrayed the industrial world’s chemical laboratories as the utopian realization of human triumph over nature and, by extension, the inevitably dominant role the US nation itself must play as the engine behind the creation of “products superior to the natural.” Dividing the world into “smaller nations” and “greater powers,” AAAS President Roger Adams described a global order where the chemical sophisticate survived: countries “technologically unsuited to a future in a strictly chemical world” must be “grouped” with nations “which through two centuries have shown an innate ability to advance against all opposition.”2 Adams’s geopolitical hierarchy was shaped by a faith that the capacity to chemically alter raw materials was a marker of national superiority, and the ideal relationship between powerful and weak nations was one that ensured a steady flow of raw materials into US industrial laboratories.

In the aftermath of World War II, US importation and stockpiling of raw materials was pursued in the name of national security, accompanied by the promise of protection and benefits that US “resources for freedom” offered the rest of the world. The previous chapter described the solidification of the international drug control regime around efforts to limit the production and flow of coca leaves, one such raw material, channeling them into an export market geared towards US pharmaceutical stockpiles. Here the focus is on the “synthetic futures” of these raw materials: upon arrival in North American laboratories, drug control officials sought to channel and contain the productive power of these substances, even as they were chemically altered and synthesized into an array of other products. This chapter describes how the process of chemical transformation itself both extended and to a certain extent transformed policing practices; synthetic manipulations might catapult substances in either direction—legality or illegality—and government and corporate officials sought to capitalize on the need for scientific expertise to certify the “legitimacy” of the end product. It shows how narcotics control brought together efforts to manage the production of new drugs with scientific and government-backed efforts to cultivate the production of new types of people. A faith in the power of alchemy to transform the natural world into superior products linked chemical laboratories to experiments in human engineering as people and communities stretching from the United States to the Andes were drawn into grand projects that linked the testing of new drugs with efforts to transform peoples’ laboring and consuming habits as the basis for securing and expanding US hegemony.

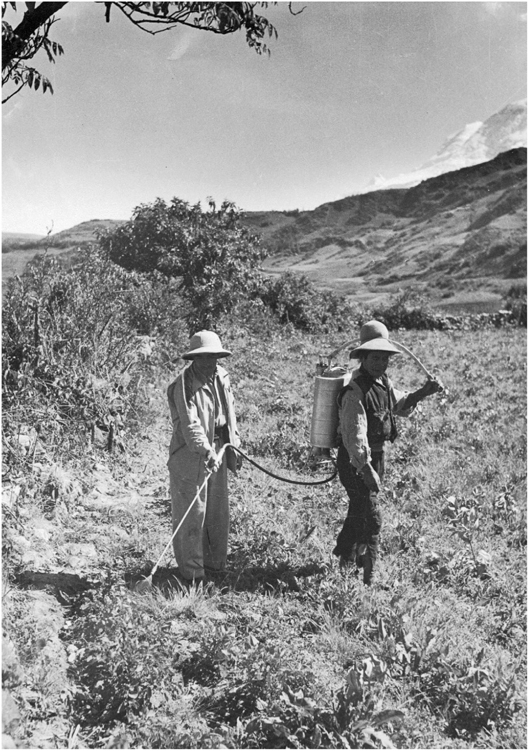

COCA’S SYNTHETIC FUTURE

The most formidable obstacle standing between US soldiers and the wad of coca leaves that could keep them active on long missions was the drug control and regulatory framework being effectively institutionalized at that time by the Treasury Department’s own Federal Bureau of Narcotics. The US Army’s laboratory-driven experimentation with chewing the leaves and making tea infusions reproduced the most common forms of indigenous Andean coca consumption—where the majority Aymara and Quechua communities had consumed coca leaves for centuries as sources of nutrition and energy, as a market medium of exchange, and also as an entity valued as a component of healing, religion, and ritual. And in simulating such activity the Army researchers threatened to undermine one of the central tenets of the emerging drug control regime: that there was no medical value, but rather numerous dangers, attached to the consumption of coca leaves in their natural state. The legal assault on raw materials consumption—the chewing of coca leaves—was a combination of the effects of US narcotics law and its determining influence on UN drug control initiatives. In relation to the legal narcotic drug trade, the US government allowed only the importation of raw materials; all controlled substances in domestic circulation (or for export) had to be manufactured within the country. The UN Commission of Enquiry on the Coca Leaf traveled through the Andes in 1949 and called for the elimination of indigenous consumption of the coca leaf in its raw material state. The “supply-side” control orientation of the increasingly powerful drug regulatory regime meant policing officials sought to confine the circulation of raw materials to internationally designated “legitimate channels.” UN and US experts defined legitimacy in this context according to the industrial world’s determination of “scientific and medicinal need,” entrenching a North–South global order where the industrial powers continued to lay claim to the raw materials of the “smaller nations.”

These considerations informed FBN Commissioner Harry Anslinger’s opposition to a planned 1950 study on coca leaves and fatigue led by scientists working for the US Office of Naval Research. Dr. Robert S. Schwab was directing the study at the Massachusetts General Hospital, and when he turned to Merck and Co., Inc. to supply him with coca leaves from their stocks, Anslinger intervened to halt the shipment. Anslinger was worried the research would undermine Andean acceptance of the regulatory framework being promoted at that time by the United States and the United Nations (where he presided as the US representative), and wanted to reassert the FBN’s influence over national drug policy. He explained his objection by highlighting “the primary aim of our government . . . has been to secure control of these drugs at the botanical source.” A series of exchanges between Commissioner Anslinger, Dr. Schwab, and Commander J.W. Macmillan of the Office of Naval Research provide perspective on contemporary debate over the promise of scientific research to American power, the definition of “legitimate” medical and scientific use of narcotics, the imperatives of international drug control, and the dangers of certain sites and forms of consumption. The incident reveals much about the nature and direction of US involvement in the coca commodity circuit and the intersection of science and drug control at that time. As Anslinger explained:

The fact that a domestic scientific project was in progress in the United States, involving the study of the effect of chewing of coca leaves on fatigue, would have a most unfortunate effect on our efforts to achieve international agreement on limitation of production of the leaves to medical and scientific needs. Accomplishments in this direction have been based on the tentative assumption that the use of coca leaves for chewing is neither medical nor scientific. Without knowledge of the official findings of the Commission of Inquiry, I nevertheless feel strongly that the practice of chewing coca leaves should never be recognized as legal.3

His insistence that coca leaf chewing “should never be recognized as legal” sought to shut down that line of scientific inquiry, and despite his use of the word “tentative,” due to his friendship with the head of the UN commission which had traveled through Peru and Bolivia in 1949, Anslinger in fact already knew the United Nations planned to recommend eliminating indigenous consumption of coca leaves in their 1950 report. And with this knowledge he argued that the principle of limitation was defined according to select medical and scientific ends, and that the coca leaf in its raw material state, “for chewing,” could not be—within the framework established by the drug control regime—a legitimate consumer commodity. Anslinger cautioned that the planned research might be used by proponents of coca leaf chewing to bolster their position: “It seems to me that those disposed to challenge such findings and to seek legal recognition and acceptance of the habit of chewing the coca leaf, would attempt to use your findings if successful, as an argument for their position.”4 Invoking international obligations—and a system of controls the United States did so much to influence—Anslinger argued that chewing the coca leaf undermined the tenets of the international system by appearing to validate claims of the unreworked raw material’s potential benefits.

Significantly, the commodity form was directly linked to legitimacy. Then and now virtually all coca leaves (legally) exported from the Andes were imported by US manufacturers. At the time Anslinger was presenting these arguments, the two pharmaceutical houses, Merck and Maywood Chemical Works, that held exclusive government licenses to import coca leaves, were both conducting research on the leaf’s active properties, reworking its form, parsing its constituent elements, and repackaging them in other states, or as elements of different commodities, before making them available for consumption. This process, in part, embodied the “alchemy of empire.” The raw material coca leaf was to be cultivated exclusively as an input into a North American manufacturing process; coca was to be transformed, derivatives extracted, and new products synthesized in laboratories, before it could become a legitimate commodity. The commodity itself then was presented as the triumphant output of US ingenuity—rather than as the product of the international network of labor and raw material from which it was derived.

The logic of control attached to the commodity form, worked to the advantage of US economic power, and was bolstered and depended on Western scientific authority. This further explains the urgency of the Commissioner of Narcotics to stop the Navy research project: it threatened to give the imprimatur of the most sophisticated scientific laboratories to the age-old practice of coca leaf chewing. The lead researcher on the project, Dr. Schwab, explained to Anslinger that “Merck Co.,” his supplier of coca leaves, had forewarned him that FBN objections might arise. “It was for this reason” that the study was carefully designed to be “an essential pharmacological investigation . . . using this drug as a means of ascertaining information and data in the general study of fatigue.” Dr. Schwab presented the raw material as a pharmacological input rather than the object of study itself. Drawing attention to the advanced technical equipment available to his lab, in contrast to the “apparatus available” to the UN researchers in the Andes, he suggested his work might have widespread scientific value, could be kept confidential if necessary, and wrote in bold underline to emphasize there was “no intention at any time“ to introduce coca leaves “into this country as a remedy for fatigue.”5 Despite this effort at reassurance, it was the very potential for scientific success that threatened to undermine drug control tenets. Anslinger urged the doctor to reconsider; affirming his belief in the research project’s limited intent, he emphasized the difficulty in keeping “such work confidential,” and argued “the natural consequence” of scientific study into the fatigue-relieving power of the leaf would “stimulate others to a practical application of the proved thesis.”

While elaborating the potential unintended consequences of such research, Anslinger’s argument exemplified how scientific authority was influencing the legal parameters of the drug control regime’s effective domain. While claiming “I deeply respect the importance of fostering rather than deterring scientific research,” Anslinger went on to say: “I am fearful of an attempt being made to expand a scientific use such as you have in mind into a so-called legitimate use which is neither medical nor scientific, and which can not fail to prejudice the proposed International Agreement to limit the production of these leaves to medical and scientific purposes only.”

The boundaries of legitimacy within narcotics control were defined by assessments of a substance’s “medical and scientific” value, even as the FBN sought to limit scientific research that might produce outcomes contrary to its own drug control goals. Coca leaves, according to the parameters of narcotics control, only gained medical and scientific value after being transformed into other substances. The dangers within the leaf could only be contained in this way—a proposition that was tied both to the commodity form and, more specifically, to an effort to channel the leaf’s potent alkaloidal content toward specific, controlled ends. What made coca leaves definitively illegitimate consumer items was the “strong probability that the chewing of these coca leaves, containing cocaine, has a potentiality for the establishment of addiction and possibly other deleterious effects.”6 Alchemical power here was twofold. First, the chemical laboratory exercised the exclusive power to render dangerous raw material legitimate. Secondly, in a circular fashion, the laboratory itself characterized coca leaves as vehicles for delivering the alkaloid cocaine, defined the drugs’ promise and peril (cocaine being “addictive”), and galvanized the system of control accordingly.

The scientific logic emerging from laboratories informed narcotic control efforts as regulators invoked the cocaine content of coca leaves to label them unsafe for indigenous consumption in the Andes. This was evident when the UN commission concluded, “the effects produced by coca leaf chewing are to be explained by the action of cocaine.”7 This equation of coca leaf with cocaine became common practice among drug control advocates. The substances valued, parsed, extracted, and synthesized from the coca leaf in the laboratories of industrial countries were imported back into the Andes not only as legitimate consumer goods, but as evidence of the dangers and need for control over the nonsynthetic. At the same time, the power of the laboratory to extract the alkaloid cocaine and channel the substance into “legitimate” medical and scientific channels also meant that the by-product from which the cocaine had been extracted was now safe once again to be synthesized into still other legitimate commodities: the most famous of which was, of course, Coca-Cola. Before returning to the outcome of the Navy research effort, it is worth considering for a moment the other synthetic futures extracted from the coca leaf. In contrast to the hypervisibility of cocaine (even when hidden in miniscule quantities within a leaf), the afterlife of various other alkaloids, vitamins, and flavor-rich substances that together constituted the original coca leaf disappeared from the regulatory landscape and from the public record for researchers probing the archive.

It is striking that at the very moment the United States was leading efforts to consolidate the drug control regime around controlling raw material, the largest single licit consumer of coca leaves at that time, the Coca-Cola Company, fell off the drug control radar. Coca-Cola, unlike raw coca leaves, was a legitimate and even desirable source of energy, and during and after World War II it underwent a massive global expansion, fueling the need for ever greater quantities of raw material for the production of its famously guarded formula. And yet, despite two decades of Coca-Cola’s “special leaves” being granted legal exemption for not qualifying as any “medical and scientific use” in international narcotics law, the UN board overseeing the international trade in narcotics reported: “Since 1947, no coca leaves have been used in the United States of America for the preparation of non-narcotic coca-flavoured beverages.”8 Perhaps the alchemy of empire made this technically true—Coca-Cola did not use coca leaves, but rather substances extracted from the leaves in a laboratory. When the Office of the United States High Commissioner in Germany heard such reports, he wrote to FBN Commissioner Anslinger, asking how Coca-Cola was now obtaining its flavoring extract. Apparently French and German resentment over the company’s “aggressive advertising campaigns” was fueling talk that their governments might import coca leaves to manufacture “similar beverages themselves.”9 Anslinger urged the officer to “discourage” such imports on narcotics enforcement grounds, emphasized the many failed attempts of competitors to reproduce Coke’s process in any case, and explained the absence of “special leaves” from UN tallies as follows: “[I]t should not be overlooked that flavoring extracts are also produced from the leaves imported for the manufacture of cocaine. In the cocaine extraction process the liquids bearing the alkaloids are separated at a very early stage from the waxes which contain the flavors and each then goes its own way to completion.”10

Two categories of legitimate uses for coca leaves technically existed in international law: the use of coca leaves for medicinal and scientific purposes and for the production of a nonnarcotic flavoring extract. These categories of legitimacy would persist and would later be consecrated in the landmark 1961 Single Drug Convention. It was an important and revealing transformation in the public administration of narcotics control, however, when in the aftermath of World War II the only “legitimate” nonmedical use of coca leaves (Coca-Cola’s flavoring extract) disappeared from the official record. Since the 1931 Geneva Convention, “special leaves” had international legal provision to be used in the manufacturing of a flavoring extract. Under the convention all such leaves had to be reported and verification provided by the FBN that all the resultant active alkaloids had been destroyed under government supervision. However, during and after the war this destruction stopped and all active alkaloids were reprocessed by pharmaceutical manufacturers for scientific and medical use—or relayed to warehouses where they filled a category of narcotics accumulation exempt from the oversight of international drug control: national security stockpiles. Once this occurred, in terms of legal reporting requirements the flavoring extract was strictly a by-product of drug production, left over from leaves that might be accounted for as imported entirely for scientific and medical use. The FBN no longer reported “special leaves” to the United Nations since they were accounted for within the tally of “medicinal” importations.11 Thus, with unintended irony, the production of Coca-Cola’s coca leaf–based flavoring extract largely disappeared from international regulatory oversight because it was now primarily derived from coca leaves imported for the manufacture of cocaine.

Coca leaf flavoring extract going “on its own way to completion,” out of the international regulatory gaze, had a number of important ramifications for narcotics control and for US government and corporate power. Initially the vice president of Coca-Cola worried this absence of tracking might eventually push them out of the legitimate market altogether. He wrote to the FBN, wondering if it would be better to report imports anyway. “My reason for this suggestion is that it would seem advisable to avoid such apparent non-use of the statutory provisions regarding ‘Special’ leaves as might cause them gradually to fall into an atrophied or inoperative status.” Anslinger successfully reassured the company’s vice president that there was nothing to fear and that reporting on “special leaves” might make it seem as if the United States was actually concealing medicinal production from international scrutiny.12 This was no small worry in a context where synthetic drugs were increasingly replacing cocaine in common medical practice, narrowing even further the domain of legitimacy. Soon thereafter, Coca-Cola began capitalizing on this absence of public scrutiny to conceal its involvement in the coca leaf trade.

The shift also had an immediate impact on the pharmaceutical industry. Merck & Co., Inc. stopped importing leaves destined exclusively for cocaine production, ceding the process entirely to Maywood Chemical Works, Coca-Cola’s supplier.13 Furthermore, Coca-Cola’s strong market growth across the decade and beyond helped ensure that the United States remained the largest manufacturer of licit cocaine in the world.14 In the realm of policing the illicit, the consequences were equally profound. The shift effectively eliminated recognition of any legal market for coca leaves outside the chemical laboratories of industrial powers. And so UN officials tracking the narcotics trade could advocate for stricter raw material controls, providing the following as evidence: “The use of coca leaves for medical purposes, namely for the licit manufacture of cocaine, absorbed only a fraction of the output . . . the balance . . . was consumed for non-medical purposes—that is to say, was chewed by certain indigenous peoples of South America.”15 The only reported “licit” manufacture was pharmaceutical cocaine production, and the only recognized illicit, “nonmedical” purpose was Andean coca leaf chewing. Coca-Cola’s nonmedical use of coca leaves no longer provided a public caveat to regulators’ insistence on “medical and scientific” value, as the company’s utilization of the leaves disappeared from FBN and UN annual reports, narrowing the visible landscape of “legitimate” uses of the coca leaf and making it easier for the Commissioner of Narcotics to make his case to the Navy for limiting their research into coca leaf chewing’s fatigue-relieving potential.16

Dr. Schwab envisioned that his work might “settle for once and for all the mechanism of the reduction of the sensation of fatigue from coca leaves,” and, by doing so, advance “fundamental knowledge of this substance.”17 And Anslinger quickly countered by invoking the potential regulatory nightmare such scientific research might provoke, potentially lending credence to claims emanating from the Andes that coca leaves were legitimate items of consumption in their natural state. For Anslinger the very potency of the leaf necessitated a strict system of control. Despite FBN concern, questions of national security influenced priorities within the realm of drug research and development, and it was for this reason that the Office of Naval Research won a rare triumph over Commissioner Anslinger’s objections to research on coca leaf in its unreworked states. “By direction of the Chief of Naval Research,” Anslinger was informed of the research project’s relevance to the country’s national security: “I am sure you are aware of the real interest of the military establishment in problems of fatigue,” Commander J.W. Macmillan wrote to Commissioner Anslinger. He went on to explain, “It is our belief that only through such programs can advances in naval power and national security be ultimately achieved.” Macmillan concluded with a lofty vision to bolster the coca leaf study: “I am sure all of us are interested in the continuation of freedom for our scientists in their efforts to further our understanding of the human organism.”18

Anslinger seems to have successfully forestalled the investigation until after the UN commission published its report in May 1950, preventing the diplomatic fallout he had feared. It was not until October 1951 that Anslinger personally submitted an order for the coca leaves to Maywood Chemical Works on behalf of scientists conducting “research on fatigue among Air Corps pilots [who need] these leaves for that purpose.”19 It is worth pointing out that while the research scientists had initially placed their order for leaves with Merck, by 1951, perhaps reflecting the industry shift in production which accompanied the shift in regulatory reporting, Anslinger turned to Maywood, Coca-Cola’s supplier, to provide the experimental stocks.

The military’s ultimate triumph over Anslinger’s objections in this case was an exceptional instance, resting on invocations of military necessity, “national security,” and scientific freedom. Most research in this field being conducted in the United States at the time involved the ingestion of the cocaine alkaloid extracted from coca leaves, or experiments with synthetic substitutes manufactured entirely in laboratories. Far from focusing on the qualities of the raw material in its natural state, American scientists and doctors, military personnel, company boardrooms, and even the mainstream media looked to the wonders of new drug development and experimentation for the capacity to advance American economic and political might, societal health, and medical knowledge. And this, unlike the Navy’s interest in keeping Air Corps pilots awake by chewing coca leaves, conformed completely to the strictures of international drug control within which North American manufacturers were primary transformers of raw materials into legitimate drug commodities for the national and world market.

DEVELOPING “WONDER DRUGS”

Cocaine’s important status within the drug regulatory regime was connected to its relatively early synthesis and revolutionary role in medicine. Tests involving coca leaves, cocaine, or synthetic substitutes in this regard were emblematic of the landscape of drug development at mid-century where a whole array of “wonder drugs,” including primarily antibiotics, vitamins, painkillers, and stimulants, promised a veritable therapeutic revolution. The introduction of cocaine into medical practice in the late nineteenth century had transformed surgery, being used very effectively as a local anesthetic. While the US Navy had been interested in the stimulating properties of the coca leaf, the cocaine alkaloid extracted from the leaf was most commonly used not as a stimulant but rather as a painkiller. Anesthesia has always been a hazardous aspect of Western surgical practice, liable to produce toxic reactions resulting in death. This toxicity—primarily tied to the dosage given and the variability of human reactions to it—sparked much research into finding less toxic substances. While cocaine continues to be “used as a topical anesthetic by ear-nose-and-throat surgeons,” numerous other synthetically manufactured drugs based on cocaine—drugs such as procaine (also called novocaine), lidocaine, prilocaine, and others—have also found their place in Western medical practice. Some laboratory-manufactured painkilling drugs, such as novocaine, continue to be widely used. Others, such as cinchocaine and bupivacaine, were discarded after discovery of their “considerable level of toxicity.”20

All of these failures and successes were part and parcel of the methods deployed for the “advancement” of Western medicine. In the 1940s the promise such synthetic substitute drugs offered was great, spanning policing, economic, diplomatic, and medical worlds. Limiting US dependence on raw materials promised to eliminate what William McAllister characterizes as the drug control regime’s “excess production dilemma,” the overproduction of raw materials that might slip into illicit channels.21 The Chief of the Addiction-Producing Drugs Section of the World Health Organization (WHO) articulated this sentiment: “Many believe that, from the viewpoint of the efficiency of control, it would even be better to be, for legitimate medical purposes, not dependent on substances manufactured from agricultural products, provided, of course . . . drugs of purely synthetic origin, are at least as good.”22 Limiting the flow of raw material also had the potential to increase US economic and diplomatic leverage if it dominated the production of synthetics. The power of synthetic drug alternatives was evident from the circumstances of their genesis: Allied World War II embargoes that propelled German chemical innovations to overcome raw material shortages. The first generation of synthetic narcotics, hailed as harbingers of a “drug revolution,” were all “discovered in Germany during the war.”23 US observers believed that synthetic drugs might reduce dependence on foreign imports while also reducing manufacturing costs. In the war’s aftermath, “old sources of supply” had opened up again, but as Business Week reported, “labor costs for collecting the plants are higher now. So the trend is definitely toward replacing imported botanicals with US-made synthetics. Manufacturers can often produce these synthetics more cheaply than they can import the plants.”24 And finally, as embodiments of the technological wonders of scientific research and capital investment, laboratory-synthesized drugs seemed to offer a limitless potential of yet to be discovered benefits.

War policy and subsequent defense mobilization illustrated the power of the synthetic drug not merely in political and economic terms, but also, importantly, in terms of their potential impact on the human body. The US military was an important site for drug experimentation as well as a critical consumer market for US-manufactured drugs. Often research that began in the context of helping soldiers overcome ailments would subsequently become incorporated into civilian medical practice. It was often military needs initially that determined which drugs were developed and to what ends. Doctors began testing procaine (novocaine) on injured soldiers at Fort Myer, Virginia, to minimize the pain resulting from “acute sprains and strains of ankles, knees and backs.” The success of these initial experimental uses of the drug were made public by Newsweek as it enthused, “Men who had hobbled and been helped to the hospital were able to walk naturally immediately after treatment and were quickly returned to heavy duty with no ill effects.”25 Research on procaine’s possible uses was extensive and offered other advantages beyond its painkilling powers. Dr. Ralph M. Tovell of Yale University and chief of anesthesiology at Hartford General Hospital, “among the first to persuade the Army of the United States to treat soldiers’ wounds with procaine,” found in his experiments one advantage of the drug was that it “was less habit forming than morphine.”26 Dr. Tovell and other researchers at universities, hospitals, and military clinics, during and after the war, experimented with procaine for a wide range of therapeutic possibilities. By 1947 while “the subject was one on which much work by anesthetists and other doctors must still be done,” procaine as described by the president of the International Anesthesia Research Society “gave promise of developing into an aid for sufferers of arthritis, gangrene, diabetes and similar afflictions.”27

FIGURE 5. Merck and Co., Inc. Louis Lozowick's artistic depiction of an aerial view of a Merck chemical manufacturing plant, commissioned by the company for an advertisement. The lithographic print captures American modernist infatuation with the machine age and industrial innovation, and the pharmaceutical giant's iconic place within it [Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of Adele Lozowick © 1944, Lee Lozowick].

Clearly the ailments such drugs might relieve made them beneficial to realms outside of the military; however, it is important to note that this early emphasis shaped the landscape of drug production and was tied to an anticipated consumer market. Along with the creation of painkillers, the first major breakthrough in synthetic drug manufacturing, hailed as a revolution in pharmacy, was to combat malaria among the armed forces deployed to tropical countries during World War II. In a study of the history of this development the WHO explained: “[W]hen Anglo-American forces landed in North Africa, Indonesia [a natural source of quinine provided by the chinchona tree] was in the hands of the enemy. The health authorities no longer had free choice of drug and so quinacrine was prescribed. . . . It can be said that the ‘era of the synthetic antimalarials’ dates from that time.”28 The US Office of Scientific Research and Development (OSRD) launched mass production of penicillin during the war as part of the agency’s mandate to “initiate and support scientific research on medical problems affecting the national defense.” In a report to the US president entitled Science: The Endless Frontier (which became the basis for the establishment in 1950 of the National Science Foundation), the director of the OSRD, Vannevar Bush, linked government-sponsored drug production to the success of the war effort. What Bush termed the “physiological indoctrination” of soldiers (with drugs) provided critical support against “the disastrous loss of fighting capacity or life.”29

As military priorities led to innovations in drug development, the laboratory gained increasing importance as a source for manufacturing drugs synthetically, to avoid dependence on raw material flows which might be disrupted by war or political instability, and to empower soldiers in their work. The production of laboratory-synthesized drugs for military consumption also made them available for other consumer markets. Bush celebrated how the war’s “great production program” made penicillin “this remarkable drug available in large quantities for both military and civilian use.”30 In the civilian realm drug control and development priorities also reflected the unequal distribution of power internationally. For instance, while synthetic drug innovation would remain valuable for future military deployments, the same drugs became valuable resources especially for use by other travelers, most frequently tourists or business employees working for North American or European companies.31 The WHO described how by 1953 synthetic antimalarials made “possible traveling, staying or working in the endemic regions with results equal or even superior to quinine.” It was clear the benefits derived from such drugs were not distributed equally. The WHO advised that it was necessary to extend “this protection and not to limit it to non-immune, non-indigenous persons or those working for them.” As the study concluded, “Among the indigenous population the children are those who are non-immune. It is certain that so far few children have benefited from preventive medication. . . . Although the era of synthetic antimalarials has arrived, the social position has not greatly changed.”32

This “social position” of drugs was true of both the sites and bodies upon whom their development relied for testing as well as the populations initially envisioned as their primary consumers. Thus drugs tested on soldiers for soldiers and other military personnel would also become useful to the corporate and pleasure-seeking visitors in colonized or “undeveloped” countries, traveling from the countries out of which the soldiers initially came. The international “social position” of a drug was influenced by the objectives spurring its initial development, and also by disparities in distribution and popular access to it. Until the “distribution problem” was solved in less developed parts of the world, if present conditions were not “greatly changed and if economic development is not accelerated, only temporary and non-indigenous residents will greatly benefit from the advances made.”33 Scientists working in the field at mid-century were aware of inequalities in access to newly manufactured drugs, yet the promise such drugs held was not questioned. This then created an opportunity for drug diplomacy, whereby symbolic and material efforts to redress uneven access, particularly among populations in the non-industrial world, became a central component of US (and increasingly Soviet) efforts to foreground health initiatives as exemplars of benevolent superpower intent.

Public health diplomacy—including the celebration and distribution of wonder drugs as markers of the pinnacle of Western medical advancement—became a prominent public component of projections of American power in the world. In October 1950, Assistant Secretary of State for Economic Affairs Willard L. Thorp declared, “World-health improvement has become a major concern of American foreign policy. Health has become recognized as a major factor in economic and social progress throughout the world—and thus in the preservation of peace.” The US surgeon general echoed such sentiments, explaining that US Army and Navy wartime involvement in civilian health problems in “far-flung combat theaters” and in “liberated or conquered areas” provided a strategic precedent for the ways in which the “promotion of world health came to be recognized as a major instrument for attaining our goals of world peace and prosperity.”34 As the United States sought to step into the power vacuums left by World War II and collapsing European empires, public health initiatives provided a seemingly neutral and unimpeachable realm of intervention. In a geopolitical context animated by anticolonial movements and burgeoning Cold War rivalries, drug trade regulations ensured industrial powers’ virtual monopoly over the manufacturing of legal drug commodities, while providing a formidable weapon in competitions for global influence.

The wonder drugs were hailed by private and public spokespeople alike as critical tools for gaining allies and securing US power and influence in the world. In 1955, Business Week celebrated the “fantastic growth” of US drug sales in foreign markets by emphasizing the humanitarian implications: “Millions of people in the underdeveloped parts of the world . . . have become acquainted with ‘miracle’ drugs since the end of World War II.”35 The advances of Western science were ultimately (if unevenly) to be exported to the rest of the world to assist in its “development.” The article’s message was dramatized in a split image where a graph depicting the growth in US exports is directly related to the work of Western medical practitioners in the “underdeveloped” world, in this case with the administration of eyedrops on a small “desert child.” The ideology that accompanied US economic expansion often relied on such representations of the benevolent and unquestioned progress US products brought to peoples of the world—people who were depicted as being unable to provide for themselves. While many drugs developed did indeed transform life expectancy and alleviate illness, often the resources invested in them inherently structured drug development not only initially toward helping the ailments of privileged populations, but also toward creating a global dependence on Western manufacturers whose drugs replaced indigenous medicinal plants in the very regions where they were cultivated.

Beyond this structuring of the international drug economy to the disadvantage of raw materials–producing countries and providing powerful diplomatic leverage to drug-manufacturing countries, it also valorized Western science often in disregard of local belief, custom, and experience. As Marcos Cueto has described initiatives to introduce Western medical practice and medicines in Peru: “In many Andean localities Western medicine was absent; and where it was available, it was applied in an essentially authoritarian way, with an unlimited confidence in the intrinsic capacity of technological resources and little regard for the education of the Indian people. Practitioners of modern medicine . . . assumed that in a ‘backward,’ nonscientific culture, disease could be managed without reference to the individual experiencing it.”36

FIGURE 6. Graphics from a 1955 Business Week article celebrating the “fantastic growth” of US pharmaceuticals' foreign market.

Within an emerging international system for the manufacturing and controlled distribution of drug commodities, such issues were not of central concern to the confident circle of scientists and experts working in the field of development connected to poverty, nutrition, and health. Indigenous populations’ own beliefs about the foundations of medicine and health were rarely taken into consideration. Nevertheless, as with the “desert child” invoked above, they often embodied in the US public imaginary proof of the beneficence of US capitalist expansion, even reframing it as bringing health and progress to “less fortunate” parts of the world. The regime not only increasingly entrenched an international economic hierarchy between states but also provided a rationale justifying and perpetuating inequality between peoples within states. The ready objectification of the “desert child” as a site for the performance of Western benevolence and the easy dismissal of alternative cultural understandings of health were indicative of the ways in which drug control policy infused race, class, and geography into a new imperial ideology. While the history of science as a bolstering force behind European and American colonialism stretches back at least into the nineteenth century, as Ashish Nandy has argued, the post–World War II moment marked a shift as science and development became increasingly central categories of national security, and science itself became “a reason of state,” potently on display in US Cold War policy.37 As Shiv Visvanathan further elaborated: “Progress and modernization as scientific projects automatically legitimate any violence done to the third world as objects of experimentation.”38 As scientists, government officials, pharmaceutical executives, and international organizations debated the parameters of drug control, they approached indigenous people of the Third World and the poor and marginalized of the industrial world much like the raw material coca, with a laboratory-like gaze where these people were not considered independent political actors, but rather as (often childlike) malleable objects ripe for socially and chemically engineering other synthetic futures. This dynamic was clear as debates over drug control provided a setting for the working-out of great power rivalries, while reasserting the First World’s dominating influence over the economic and political trajectories of “underdeveloped” countries and peoples.

COLD WAR PROTOCOLS

For US and UN officials concerned with international drug control, the profusion of wonder drugs posed a new regulatory challenge as they worked on devising oversight mechanisms to channel manufactured drugs’ productive power—their promise and peril—to their own sanctioned ends. The dreamer behind “Man’s Synthetic Future,” the “scientific statesman” Roger Adams who was deeply involved in advancing chemistry’s role in both government and business, having served among many other posts as consultant for the National Defense Research Committee and the Coca-Cola Company,39 captured the fear lurking at the edges of the wonder: “The future may bring us a series of drugs that will permit deliberate molding of a person, mentally and physically. When this day arrives the problems of control of such chemicals will be of concern to all. They would present dire potentialities in the hands of an unscrupulous dictator.”40

This dystopian vision of nefarious forces using drugs to manipulate human bodies and social organization was the logical counterpoint to celebrations of their ability to bring “peace and prosperity.” Both projections accepted the proposition—at once celebrated and feared—that governments might use drugs to influence society (and implicitly, that the consumption of drugs—the physical impact—had predetermined social consequences). The distinction—one good, one bad—between the US military’s reliance on drugs for the “physiological indoctrination” of soldiers and a “dictator’s” use of drugs for the “deliberate molding of a person,” rested on moral, cultural, and political arguments to justify the regulation and policing of drugs, even while advancing a belief in the power of drugs to transform publics.

Such arguments held enormous weight when drug control officials sought to dictate the trajectory of drug production, distribution, and consumption, from the raw materials through to the finished goods. The “two serious new problems” first identified by the UN Commission on Narcotic Drugs (the primary body governing the international drug trade) stemmed from the “habit of chewing coca leaves” and the new abundance of “man-made drugs.” Reporting on the CND’s activities for the Washington Post, Adelaide Kerr explained how a duality intrinsic to the drug revolution generated the need for regulation: “Rightly used, many of these drugs are boons to mankind, but wrongly used they can wreck health, destroy men’s moral sense to such an extent they often turn into criminals, ruin their ability for constructive work, impoverish them, reduce them from producers and wage earners to charity charges of the state and because of these and other reasons, produce extremely serious economic and social problems for their countries.”41

The belief in the capacity of drugs to improve “mankind” relied on the depiction of drugs as powerful agents: capable of turning people into wage earning, productive members of society, or, in contrast, of transforming them into destructive elements and economic drains on the state. The government had a primary interest in securing economic advantage within the drug trade, which entailed influencing the consuming habits of the population. When framed in this way, the challenges confronting the drug control regime were twofold in the quest to realize “boons to mankind.” First was the question of determining which drugs were most valuable. Second was the need to implement regulations and oversight to ensure consumer demand for all drugs remained in legitimate channels. Drug control was not geared towards eliminating dangerous drugs; rather, it was oriented toward harnessing the productive potential of drugs and delegating the relationship of various countries and populations to the “legal” international drug trade. Controlling the flow of raw materials to limit the nature, extent, and geography of manufactured drug production was one component. Controlling the circulation and consumption of manufactured drugs themselves was another. And so, along with initiatives in the Andes to control coca leaf production, a concerted international campaign was launched, spearheaded by US representatives at the United Nations, to extend the regulatory regime’s jurisdiction to encompass new synthetic “man-made” drugs.

Public officials attending the United Nations aired these preoccupations in late 1948 when they convened to draft, debate, and ultimately adopt the Protocol Bringing under International Control Drugs Outside the Scope of the Convention of 13 July 1931 for Limiting the Manufacture and Regulating the Distribution of Narcotic Drugs (the 1948 Protocol). This treaty launched international regulation of synthetic drugs—substances previously “outside the scope” of legal supervision. Eleanor Roosevelt, the former president’s widow and US delegate in attendance, contributed to the sense of urgency as she recounted how synthetic drug production “was so easy that a single factory could flood the world market with products of that category,” and insisted, “the machinery for controlling narcotic drugs should be extended and modernized.” Roosevelt reported that the “United States would give its full support to the draft protocol,” and delicately tried to overcome a central point of contention among world powers about whether the protocol would apply to colonial and other non-self-governing territories: “It is hoped that the General Assembly would approve the protocol during the current session and that all Governments would apply it without delay in their dependent territories.” In a series of exchanges that augured the role drug control would increasingly play in anticolonial and Cold War conflict (addressed more extensively in the next chapter), conflict surrounding passage of the protocol mirrored those accompanying global power realignments.

The source of controversy was Article 8 of the proposed UN protocol, which delegated to imperial powers, including the United States and United Kingdom, autonomous determination over whether the protocol’s rules would extend to territories under their nations’ control. The Soviet delegates challenged the proposal on a number of grounds. They argued it was a mechanism for metropolitan powers to bypass oversight and it exemplified a negligent lack of concern for “unhealthy conditions prevalent in those Territories.” What followed was a back-and-forth verbal exchange in response to this assertion that Article 8 rendered drug control imperially selective and self-serving. British officials defended the clause as protecting the right to representative government in its territories (which could choose to sign on or not), challenged Soviet depictions of it as “an escape clause” (that would allow the United States and United Kingdom to have unregulated drug markets in regions under their control), and explained, “the United Kingdom did not wish and was not able to impose its own point of view on the territories placed under its trusteeship.” US representatives supported the British; however, they emphasized the distinctiveness of their colonial administration whereby “in accordance with their usual practice,” the protocol would automatically apply “to all territories for the foreign relations of which they were responsible.” The Soviets persisted in their opposition, exhibiting their own paternalist ambitions as they accused the United States and United Kingdom of malicious colonial neglect: “The abolition of such colonial clauses would convince the Native peoples that the metropolitan authorities were seeking to improve their administration; their retention, on the other hand, indicated a lack of desire to promote the real interests of colonial peoples.”

As the exchange heated up, the fault lines of postwar diplomacy were clearly on display. The symbolic jostling around the concern of superpowers for the peoples of colonial territories reflected a geopolitical division whereby the United States defended its own and England’s imperial administration while the Soviet Union postured as an ally of “colonial peoples.” All three presumed the superiority of industrial world power and expounded the benevolent possibilities of exporting their own visions of progress to other parts of the world. It was not the system of control being contested, all sides agreeing that drug control “would be of such obvious benefit to them [colonial peoples],” but rather the political principles delineating its effective domain. Symbolic posturing became central to negotiations over drug control. The USSR proposed eliminating Article 8 “based on a desire for equality for all peoples,” and the British argued the “steady advance towards independence for non-self-governing peoples” meant they “should be allowed to decide whether they wished the protocol to be applicable to them.”42

The balance of power at the United Nations ensured that the interests of colonial powers carried the day; the protocol was adopted, including Article 8, despite Soviet reservations. In the midst of postwar reconstruction, colonial readjustments, Cold War tensions, and the political challenge posed by a growing number of newly independent states, drug control efforts provided one way for industrial countries, particularly the United States, to secure international dominance through a selective regulatory apparatus portrayed as an act of international benevolence. The delegate from India remarked on the unprecedented embrace of drug control, comparing it to burgeoning efforts to control atomic power:

It was easy to imagine the sensation it would cause if the First Committee were to adopt unanimously, after a single day’s discussion, a convention for the control of atomic energy. Yet the difference between the two problems was not so great. Both were the result of progress achieved through science, progress which might be put to either good or bad uses. The destruction which the atomic bomb could wreak, though more limited in its extent, was more spectacular, whereas synthetic drugs were able to do great damage insidiously and continuously, on a larger scale. They destroyed the mind before they destroyed the body.43

Political, economic, and cultural factors influenced which drugs under what circumstances would fall under the system of control, something implicitly acknowledged in this declaration that scientific “progress” could be put to both “good and bad uses.” It was the drug control regime itself that delineated the boundaries of legality—when an individual, official, institution, or government was putting drugs to “good” or “bad” uses—and officials administering the system based these determinations on the authority of Western scientists, inevitably and profoundly shaped by power hierarchies and cultural bias. Arguments over colonial authority exhibited this tendency. So too did the language and categories of enforcement enshrined in the 1948 Protocol, particularly the assignation of the label “addictive.” The idea that opium and cocaine were “addictive” provided the foundational justification for the entire drug control regime. The deployment of this term in negotiations over the 1948 Protocol showed the ongoing manipulation of the concept to augment the capacity of industrial countries to influence the lives of people and communities around the world in very concrete ways.

The CND drafted the 1948 Protocol, which introduced regulations to limit the manufacture of and monitor the trade in certain synthetic drugs to be overseen by the Drug Supervisory Body (DSB). It delegated to the WHO the authority to determine which substances should be controlled based on whether “the drug in question is capable of producing addiction or of conversion into a product capable of producing addiction.”44 National governments adhering to the treaty had to report to the UN secretary general the discoveries of synthetic drugs that might prove “liable to the same kind of abuse and productive of the same kind of harmful effects” as those attributed to coca and opium, and the secretary general in turn would notify the CND and the WHO. The WHO made a scientific determination of a substance’s potential danger and the CND launched regulation when necessary. The Preamble to the 1948 Protocol summarized the treaty’s origin and function: “Considering that the progress of modern pharmacology and chemistry has resulted in the discovery of drugs, particularly synthetic drugs, capable of producing addiction,” the treaty placed these drugs “under control in order to limit by international agreement their manufacture to the world’s legitimate requirements for medical and scientific purposes and to regulate their distribution.” The 1948 Protocol did not apply to all synthetic drugs, but exclusively to drugs deemed to have addictive properties similar to opium and cocaine. The two original “narcotic drugs” subject to international control, the poppy plant and coca leaves and their valued derivatives (opium and cocaine), remained entrenched as the benchmark for all other drugs in determining whether they should be deemed addictive and regulated as “narcotics.”

Drug control officials identified “addiction” as the object of their regulatory and policing endeavors, and defining the concept became an important aspect of establishing the regime’s effective domain. Determining the “addictive” properties of synthetic drugs became the designated responsibility of the WHO’s Expert Committee on Drugs Liable to Produce Addiction, which in 1949 defined its task as follows: “The Expert Committee . . . is to investigate the extremely complicated situation created by the production of a whole group of new synthetic products whose analgesic properties produce an effect analogous to that of morphine and are habit-forming or which lend themselves readily to conversion into drugs capable of producing addiction.”45

Synthetic opiates were the largest category of drug leaking into illicit channels at that time. Drug control authorities, particularly in the United States, also worried about the illicit circulation of synthetic versions of cocaine. As early as the 1930s, studies were done to help “government chemists . . . identify both cocaine and novocaine separately.” This grew out of police anxiety that “illegal cocaine seized by the Narcotics Bureau . . . had been adulterated with novocaine,” or even completely substituted by it.46 In 1945 the FBN failed to secure a conviction for illicit novocaine seized at the border when the defense attorney successfully argued the drug was not a derivative of the coca leaf and consequently did “not come within the purview” of federal narcotic law.47 Anslinger raised alarm and, concurrent with international efforts to control synthetics, the United States amended its narcotic law to “redefine the term ‘Narcotic Drugs’ to include synthetic substances which are chemically identical with a drug derived from opium or coca leaves.” As an FBN circular described the adjustment to its agents, “it was decided to amend the law so that such distinction [whether synthetic drugs were ‘narcotics’] would be unnecessary.”48 According to the FBN, the time for policing synthetically manufactured drugs as “narcotics” had arrived.

Drug control now targeted synthetic drugs believed to mimic the presumed addictive qualities of opium and cocaine. The international drug control regime’s emphasis on “drugs capable of producing addiction” bolstered international efforts to limit the circulation of particular substances, like coca, and in the process justified policing people deemed threatening to the social, political, and economic status quo. This was evident when the CND investigated the “problem” of coca leaf chewing in 1949 and turned to the WHO Expert Committee for help. The CND asked to be furnished with “definitions of the terms ‘drug addiction,’ ‘addiction forming drugs,’ and ‘fundamental structure of addiction-forming drug’ . . . to illustrate such definitions by references to appropriate drugs.” In response to this request, the Expert Committee explained that essential to defining the notion of “addiction” was distinguishing it from the term “habit-forming.” The head of the Expert Committee elaborated this point in an exchange with its US delegate: “In the Paris Protocol of November 1948, and even as early as in the 1931 Convention, the word ‘addiction’ has been used in preference to ‘habit.’ In my opinion, ‘addiction’ corresponds better than ‘habit’ to the meaning. There are many habits which have nothing to do with addiction. Therefore, ‘addiction-forming’ drugs might be a more appropriate expression than ‘habit-forming.’”49

The US delegate, Nathan B. Eddy—who served as a medical officer at the US Public Health Service (USPHS)—concurred and emphasized, “at least for control purposes ‘addicting drug’ is a more exact term and nearer the meaning intended than ‘habit-forming’; as you say, the latter is too comprehensive.”50

“For control purposes,” then, “addicting” was determined to reflect the greater social menace posed by the consumption of certain drugs. The Expert Committee went on to officially “caution against the erroneous characterization as addiction-producing, of such substances or drugs which in fact do not bear a real addiction character, but merely create habituation. The use of tobacco is an example, alcohol is another.” The “real addiction characters” of certain drugs as defined by the WHO was unique in many ways “from many earlier ones, given by pharmacologists and psychiatrists, in the sense that they include the social aspect, the harm done not only to the individual but to society.”51 So, the dangerous aspect of drug consumption, according to the parameters of the emerging drug control regime, resided not only in an individual’s consumption habits or even the physiological action of the drug on a person’s body, but also in the threat these bodies posed to the larger society. As such the definition inherently structured into the drug control regime the power of cultural, racial, class, gender, national, and other biases to influence the determination of what constituted a menace to the community.

Such biases were evident in the work and conclusions of the UN Commission of Enquiry on the Coca Leaf, as discussed more extensively in the previous chapter. It was widely acknowledged at the time, as described in the US publication Natural History in 1947, that “the coca habit is more universal among Andean Indians than the tobacco habit is among civilized people.”52 And the fact that the habit of coca leaf chewing, unlike tobacco, was prevalent among a racially distinct and economically impoverished population who were not considered “civilized,” made the attack on coca seem all the more necessary. The WHO’s logic reflected larger structures of power operative in the world at mid-century. And the parameters of the drug control regime—those drugs (and people) that got targeted—were flexible in defense of this larger vision. When specifically asked to address the question of coca leaf chewing, “The Expert Committee came to the conclusion that coca chewing is detrimental to the individual and to society and that it must be defined and treated as an addiction, in spite of the occasional absence of those characteristics.”53

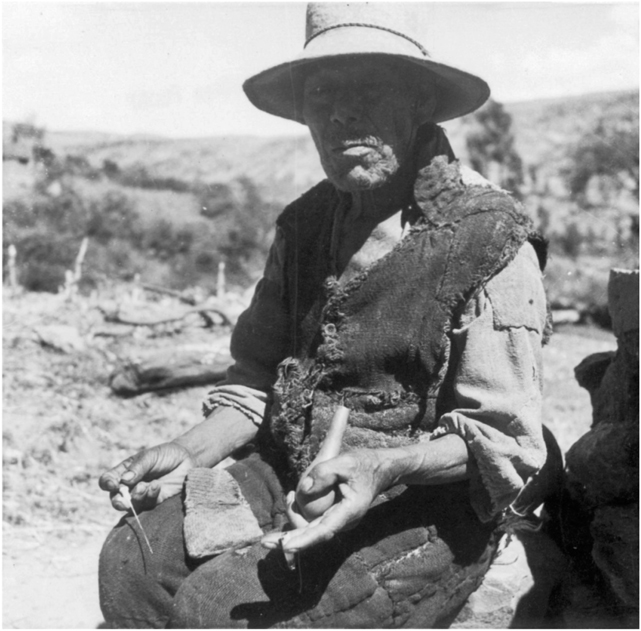

FIGURE 7. A Peruvian peasant in Vicos in 1952 holding a coca leaf bag, lime dispenser (to dip into while chewing the leaf), and a cigarette in his hand. According to drug control officials, tobacco use constituted a “habit” while coca consumption was an “addiction.” [“Vicosino Holding Coca Bag, Lime Dispenser.” Photograph by Abraham Guillén. Allan R. Holmberg collection on Peru, #14–25–1529. Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections, Cornell University Library.]

Scientists declaring coca addictive, despite “the occasional absence of those characteristics,” suggests the definition was more socially than scientifically based, a phenomenon long true in the history of the policing of cocaine.54 As early as the 1920s scientists drew clear distinctions between the physiologically addictive properties of opiates—where symptoms of withdrawal were manifest—in contrast to cocaine. Nevertheless, cocaine users in scientific and popular representations continued to be identified as “addicts.” In a 1929 article in the Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics the social aspect of addiction trumped the “absence” of physical symptoms: “Although, therefore, in contrast to morphine, we consider a tolerance to cocaine in the pharmacological sense as unproved, we are compelled to recognize the fact of a passionate addiction.”55 The threat posed by such addiction, first diagnosed among consumers in the industrial world in the 1920s, was similar to that which would animate attacks on coca leaf chewing in the Andes in the 1940s and 1950s. It resided in the perception of the related uncontrolled behaviors deemed “irregular” or socially undesirable. As the author of the textbook Practical Pharmacology characterized the threat, cocaine was “a substance to produce complete abandon and an utter disregard for consequences and future . . . the normal person gets no pleasure from injections of cocaine.”56 And elsewhere, “Chronic cocainism produces marked sexual irregularities in man, usually increasing libido by allowing freer play of the imagination; most female cocainists exhibit nymphomania.”57 Beyond the implicit gendered hierarchy of presumed independent thought even among addicts in this particular characterization, the politics of declaring and identifying a “passionate addiction” was rooted in racial, gender, and class conflicts in both the Andes and the United States. The medical concept “addiction” was a category most meaningful among the field of international experts who defined and enforced it, not exclusively as a scientific phenomena, but as a social construction of the object, behavior, or population to be controlled—through imposed isolated or refashioning into productive members of society.

By the 1950s such definitions of addiction drew upon scientific research in both the Andes and the United States. Studies of indigenous coca consumption helped establish the baseline for the drug control regime’s policing of “addiction.” In the industrial world, other vulnerable populations would become the objects of scientific inquiry into the addictive properties—and attendant need for regulation—of an array of new synthetic substances being churned out by pharmaceutical laboratories.

THE NARCOTIC FARM

At mid-century, drug development and experimentation (particularly when involving the use of human subjects) tended to occur (or at least get documented) within public institutional settings. In both the Andes and the United States the test subjects for such research were drawn primarily from military personnel, prisoners, asylum populations, committed “narcotics addicts,” and poor people in need of medical assistance or cash. This was dramatically on display at the US Narcotic Farm run by the USPHS in Lexington, Kentucky. As the Commissioner of Narcotics testified before Congress about the work being done at this institution:

We are having a drug revolution. New drugs are coming into the field of medicine, all of which, so far, were discovered in Germany during the war. . . . Every country in the world is now going to ascribe to the protocol on synthetic drugs. We will put these new drugs in the same compartment as morphine and heroin and other derivatives of opium and the coca leaf. All of those organizations are looking to one place, and only one place, where we can get accurate information, and that is the work at Lexington.58

And indeed, the CND, the National Research Council, the WHO, and a range of pharmaceutical firms all drew upon the work done by scientists working for the USPHS at Lexington to determine the addictive potential of various new substances and, by extension, the reach of drug control. The Narcotic Farm was jointly run by the USPHS and the Bureau of Prisons and it housed a research unit—the Addiction Research Center which was at that time the only research center in the world that was conducting studies on “addiction” using live subjects—i.e., prisoner-patients who had previously been identified as “addicts” and were deemed, as such, extremely valuable for testing the addictive potential of new drugs. FBN Commissioner Anslinger exulted, “There is no question about the research work there. It is the finest in the world. The research is not conducted upon animals, but upon individuals who are themselves addicts.”59

A new politics of value was being advanced with the growth of American power and it was profoundly on display in the market’s influence on laboratory agendas. At Lexington, market and scientific value merged in the efforts to cultivate valuable people and to cultivate valuable drugs. A guiding principle of the research done at Lexington was to develop drugs that might be substitutes for other drugs—value, as with money, relied as much on a substance’s fungibility, on the capacity to replace existing drugs with similar, but more strategically valuable versions, than on any intrinsic health benefit. And value in this context was part of a complex diplomatic, economic, and legal calculus.

As the tenets of international drug control were being construed around the policing of “addictive” substances, the National Research Council’s National Committee on Drug Addiction made it a priority to collaborate with the pharmaceutical industry in an effort to “systematically set out to review all compounds that promised to achieve analgesic effects without producing physiological symptoms of tolerance and withdrawal.” Science and pharmacology promised to relieve social conflict. “The committee maintained that through substitution, industrial production of alkaloids could be ‘reduced to a minimum,’ thus lessening the police authority necessary to control the situation.”60 Thus the research at Lexington was not so much designed to rehabilitate “addicts,” who were largely considered to be unredeemable, but rather to test out new synthetic substitutes being cranked out by American pharmaceutical laboratories. Experimental drug trials for new compounds being put out by companies including Merck, Eli Lilly, Parke-Davis, and many others benefited from the research conducted at Lexington. This research reverberated through the drug regulatory regime. In justifying annual appropriations to continue the work at Lexington, the FBN commissioner reported to Congress in 1947: “Not so long ago I went to get demerol, a new synthetic drug, under control, and I had to prove that it was a habit-forming drug and it was only because of the work at Lexington that I was able to convince the Ways and Means Committee that this drug should be under control.”61

Demerol was just one of a number of drugs that fell under the purview of the international 1948 Protocol based on research into addiction being conducted at the Lexington Narcotic Farm.62 The work at Lexington helped establish both national and international definitions of “addiction” that influenced the orientation of international drug control. For a country intent on cultivating mass consumption, the policing of addiction offers a striking window onto the political economy of US power. Not only was the category of “addiction” notoriously difficult to define when detached from social and cultural understandings of it, but as a legal category it structured enforcement according to the power of racial, national, cultural, and other biases to determine whose consumption practices were targeted as a menace to the larger community. Unsurprisingly at Lexington, “The researchers were almost entirely white, upper- and middle-class professional men who experimented on poor, lower- and working-class, ethnically and racially diverse addicts.”63

This hierarchy was a direct consequence of the seemingly neutral science that had been brought to bear on the definition of addiction. The medical director of USPHS at Lexington, Kentucky, described his research conclusions on the nature of addiction before an audience of the American Psychiatric Association in 1947: “The term ‘addiction’ need not be confined to the use of substances. Persons who pursue certain practices to their own or the public’s inconvenience, harm or peril are sometimes a greater problem than those who misuse a substance. It may well be that internal or external difficulties responsible for the unwise pursuit of a practice and those responsible for the misuse of a substance are similar.”64

The social and the biological were intimately linked, he suggested, and addiction was a manifestation not merely of a drug’s impact on the human body, but of a person who already exhibited socially dysfunctional behavior. It is striking how notions of social conformity rooted in a particular model of consumer capitalism were prominently on display. As historian Nancy Campbell explains, the test subjects at Lexington were deemed socially irredeemable and, as such, incredibly valuable as “research material”—a sobering refashioning of people as human raw material inputs into the chemical laboratories of US capitalism. “Drug addicts, who occupy the social category of unproductive or even antiproductive, were rendered ‘useful’ through the exercise of scientific discipline at the [Addiction Research Center].”65 Echoing this logic, the medical director at Lexington testified before Congress in 1948, “Narcotic addiction is a public-health menace inasmuch as without control addiction spreads and persons addicted become submissive, ambitionless and abject.” The “typical symptoms of drug addiction” are evident in the “loss of self-control.” The doctor went on to describe the promise of social transformation such research might bring about: “In addition to this unconditioning and as a substitute for old habits, new habits must be built up; and for this reason the addict under treatment should be kept busy in some useful way during all his waking hours.”66

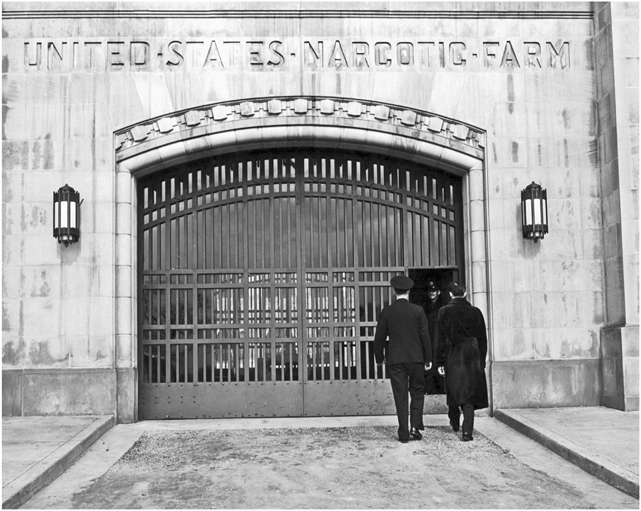

And Lexington provided an experimental context to do just that. As its original title suggests, the Narcotic Farm as a penal-research institution was also operated as a labor farm. Its institutional name would be changed to “Public Health Service Hospital” when “people began to ask where the narcotics were grown,” although it never shook the nickname “Narco.”67 Arguably narcotics were indeed being grown, or at least tested on the premises; however, the confidence behind the entranceway’s dramatic inscription (“United States Narcotic Farm”) was based on the idea of the redemptive value of productive labor. Inmates at Lexington operated a clothing factory, a furniture factory, a farm, and a patient commissary.68 The farm was intended to be self-sustaining and the other capital industries produced products “utilized by government agencies.”69 In fact, during the war the Army received articles manufactured at Lexington of “value in excess of $100,000.”70

FIGURE 8. Federal Narcotic Farm, Lexington, Kentucky. [Photo by Arthur Rothstein.]

With the revolution in drug development underway, synthetic drugs offered the opportunity to replace drugs deemed dangerous (addictive) with nonaddictive substitutes and alternatives (of course, many of the drugs produced like methadone and others turned out to be just as addictive as the drugs, in this case heroin, they were intended to replace). Similarly people deemed “antiproductive” threats to the community (convicted felons) could be put to work and, if not completely transformed themselves, might contribute to the greater social good. The logic of the laboratory was intimately linked to a vision for policing drug production and consumption, and the way this new drug market incorporated people’s bodies reveals much about the cultural and social implications of capitalist-driven modernization.

ALCHEMY IN THE ANDES

Policing and regulation were not tied simply to limitation and repression, but also to the positive production of capitalist consumer habits. This was true in both the United States and the Andes, at both ends of the economic circuit through which coca commodities flowed. In particular the policing of drug production and consumption was guided largely by identifying “addiction” as the benchmark for designating select drug consumption “illegitimate.” The deployment of a language of “addiction” to attack certain contexts of drug consumption relied on identifying the bodies of people deemed socially threatening to become the test subjects for drug development and social engineering across the Americas. The research conclusions devised from human drug experimentation in the United States would be replicated in US-led Andean projects of social engineering. US national strategic priorities incorporated a commitment to US-manufactured drugs as a component of encouraging specific models of modernization and development, defining the rights of citizenship, and controlling the physical bodies of people targeted for necessary social and cultural transformation in the United States, Peru, and Bolivia. The alchemy of empire consisted of more than simply the control of plants and physical material. It was also a process of cultivating the necessary social order, modeling the laboring and consuming habits of populations to quite literally fuel and sustain the envisioned economic transformations. In this regard, drugs were not merely valued as “commodities of commerce” but were deemed critical tools of international diplomacy and even, for an array of public and private officials, the very basis for pursuing US national security.