CHAPTER 5

The Chemical Cold War

Drugs and Policing in the New World Order

While anthropologists involved in social engineering projects in the Andes hoped their work might forestall upheavals in the mold of African liberation struggles, similar fears resonated on the floor of the United States Congress. During January 1952 annual appropriations hearings for the Federal Bureau of Narcotics, a World War II and Korean War veteran, and member of the House of Representatives, Alfred Sieminski, warned that international collaboration was urgently needed to prevent drugs being deployed as the fuel firing up global revolution: “I wonder, inasmuch as our fleet now, for the first time in history, is refueling in the Mediterranean, and great bases are being built in Africa and since Africa becomes of some interest to us, if you could pass on to your British counterparts that an Oxford graduate, later schooled in Moscow, is behind the colored unrest in the Kenya area and is no doubt the Kremlin’s No. 1 man to lead a race rebellion on that continent with the aid of drugs as fuel.”1

Rep. Sieminski’s vision, while misrepresenting Kenyan independence leader Jomo Kenyatta’s biography, nevertheless embodied the convergence of fear and global ambition that animated US discourse linking drugs to the Cold War, civil rights, and “race rebellion” in the 1950s and beyond. Persistent in this focus, Sieminski would later simplify his expression of concern: “Let us put it this way. Are drugs playing any part in the Mau Mau movement which seeks to throw the white man out of Africa?” FBN Commissioner Harry Anslinger confirmed that “riots” in Kenya had been traced to the “use of dagga, which is the same as hashish or marijuana, [and] has become widespread in Nairobi where the Government established a commission to look into the situation.”2 Referring to a recent article in Life magazine, the congressman explained his line of questioning was motivated by the worry that “American magazine and printed opinion deal well with the problem of communism and race tensions, yet little is said of the influence, if any, of narcotics in spreading both movements; in easing infiltration to carry out missions of plunder, torture, degeneration, murder and death.”3

This pairing of narcotics with communism, racial tension, violence, and political rebellion was widespread in US public life and helped drive the passage of increasingly coercive drug laws and enforcement measures at both the national and international level throughout the 1950s. Examining this heightened policing of drugs shows new mechanisms of social control that depended in large part on monopolizing the power of laboratory-manufactured commodities in both material and symbolic form.4 This discourse selectively linked narcotics to criminality in confrontation with an increasingly empowered politics of social change. The congressman’s invocation of Kenyatta depended on sets of associations increasingly articulated in a white American reaction to the threat posed by African liberation movements at home and abroad. While in fact Kenyatta did not attend Oxford (he graduated from the London School of Economics), did not use drugs to fuel rebellion (as reporter J.A. Rogers said, “They don’t need it. The indignities and the injustices they suffer are enough to drive them on,”5) and was neither a Communist nor the leader of the Mau Mau (the Kenya Land and Freedom Movement), in London he did meet with Pan-Africanists such as civil rights leader Paul Robeson, whose passport had only recently, and very publicly, been revoked due to his criticism of US foreign policy in Korea. Extensive coverage of the anticolonial uprisings fueled white fears and mobilized black solidarities. So for instance, jazz drummer Art Blakey’s “A Message from Kenya” paid tribute to the rebellion through Afro-Cuban musical forms, in a decade where the coercive powers of the state, mobilized in no small part through the pairing of drugs and war, confronted Soviet and Chinese Communism, the civil rights movement, “Negro” and Puerto Rican youth, jazz musicians, and Cuban revolutionaries.6

In the early 1950s, as the Cold War turned hot in Korea and the superpowers jockeyed for global influence across the nationalist, anticolonial Third World, the material and symbolic power of drugs was both celebrated and feared. The belief of diplomats, scientists, and pharmaceutical executives in the productive power of new drug developments was accompanied by intensified national and international efforts to identify and police the perceived dangers posed by these drugs circulating outside these authorities’ sphere of influence. The “wonder drugs,” described in the last chapter, when viewed as migrating beyond the reach of direct control, easily devolved into mediums for transmitting social and political unrest, a phenomenon frequently described by recourse to a language of disease, contagion, social dysfunction, political subversion, and criminality. This chapter follows US officials’ policing of the drug market as a constitutive element of efforts to consolidate a US-dominated capitalist economic system in the face of domestic and international challenges to its hegemony. It charts the role that “drug warfare” played in regulatory debates at the United Nations, in justifying the introduction of the first mandatory minimum sentences in the United States, and in shaping Cold War confrontations. The research reveals how a seemingly neutral logic linking science, law, health, and national security empowered policing officials to pursue perceived threats to the dominant cultural, political, and economic order. The selective policing of drugs became an important regulatory tool and rhetorically charged framework invigorating and defining the pursuit of US power.

COLD WAR DRUG WARS

World War II cemented the status of drugs as strategic materials and weapons of war. As alliances shifted in the war’s aftermath, the access of nations and people to participation within the legal market and their vulnerability to accusations of illicit trafficking, reflected the persistent power of drugs as tools for acquiring economic and political influence, as well as their symbolic importance in Cold War struggles over global dominance. By the early 1950s, US leadership at the United Nations Commission on Narcotic Drugs had established the centrality of the global drug control regime’s focus on the control of raw materials as well as ensuring that narcotic drugs, and synthetic substitutes for them, were subject to international controls. The work of the Commission of Enquiry on the Coca Leaf paired with ongoing diplomatic, political, and economic collaboration between the US and Andean nations produced in the early parts of the decade a sense of triumph at the FBN in relation to efforts to control the production of cocaine. This in turn prompted a shift in focus of US global drug policy toward efforts to extend a similar system of control over opium producing nations, nations that did not fall exclusively within a US sphere of influence. At the end of the decade when new threats to US hegemony would appear in the hemisphere, particularly Cuba, specific accusations tied to cocaine trafficking and hemispheric subversion would reemerge as central to drug policy and discourse. In the interim, the logical foundations of drug control, established during the previous decade with its alchemical power to target different substances, peoples, nations, and enemies, would be refined in polemical debates animated by Cold War and imperial rivalries.

These public debates about drugs, as agents of warfare and medicinal progress, provide a window onto the ideology of US imperialism. They also suggest the ways in which imperial ambition at mid-century, among both the United States and the Soviet Union, was articulated through a new logical framework that prioritized technological progress, scientific expertise, and economic productivity.7 The explicitly race-based arguments that had previously justified colonial conquest and genocide were increasingly replaced by arguments grounded in policing, public health, and the social sciences as the great powers battled for control and influence across the colonial and postcolonial world. The convergence of chemicals and the Cold War was on dramatic display when the United Nations convened in New York in the spring of 1952. The national and international press reported on debates at the UN General Assembly and in the US Congress as the United States, Soviet Union, and China publicly traded heated accusations over the deployment of chemical weapons in the context of the Korean War.

During the early years of the Cold War, the United Nations became a public international forum for the Soviet Union, United States, and their respective allies to articulate competing ambitions and political conflicts within a bureaucratic institutional setting where rules of procedure rather than battlefield tactics predominated. A new imperial rivalry was on display, for example, when the Soviet Union persistently challenged the seating of the Nationalist Chinese (Kuomintang) representative [exiled to Formosa (Taiwan) after defeat by the Communists in the civil war] in place of a delegation from the People’s Republic of China, and the United States defended the same. In 1952, the representative of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics began the UN’s Economic and Social Council’s First Special Session with a point of order declaring the presence of Kuomintang representatives “illegal” and “requested that that they should be expelled and replaced by accredited representatives of the Central People’s Government of the People’s Republic of China.” The US representative retorted by reiterating his country’s consistent opposition to Soviet efforts to unseat the “the Nationalist Government of China,” arguing that the proposal “should not even be considered in view of the fact that the Chinese Communist Government, in its international behaviour, and specifically in Korea, was showing open disrespect for the principles upheld by the United Nations.”8

Referring to the ongoing conflict on the Korean peninsula where US and UN forces battled the North Korean and Chinese armies, this confrontation embodied the rhetorical backdrop to a growing reliance on proxy war and the enfolding of liberation struggles within a US-Soviet bipolar global conflict. Allegations of drug trafficking played a surprisingly central role. The United States, whose influence in 1952 at the United Nations far superseded the USSR’s, triumphed through procedural maneuver, preventing the Soviet proposal to seat the Chinese government from coming to a vote. Not, however, before the USSR exacted public revenge. The Soviet representative noted “It was well known that the Kuomintang represented nobody but a group of mercenaries in the pay of the United States Government.” Furthermore, his government was “surprised to hear the United States representative mention the current situation in Korea as an argument in support of his proposal.” Countering, “As a matter of fact, it was rather the question of the bacterial warfare waged in Korea by the United States which should be discussed in the Council.”9

The United States disputed this allegation of deploying bacteriological warfare in an official report through the CND to ECOSOC only two months later, and countercharged the Chinese and North Koreans with smuggling heroin into South Korea and Japan.10 Standing accused of bacterial warfare, the United States suggested it was the accusers who sought to infect the West with dangerous substances: narcotic drugs. While on the surface there might seem to be a fundamental categorical distinction between narcotic drugs and agents of bacteriological and chemical warfare, the line in fact was quite murky when research and researchers explored the productive and destructive powers of various natural and synthetic substances; studying the destructive potential and how to cure infectious disease went hand in hand, and involved both natural and laboratory-manufactured agents.11 Moreover, Cold War rhetorical combat often relied on the implicit connection between the two.

China denied using heroin as an offensive weapon, backed by the Soviet representative’s denunciation of this “slanderous falsehood,” and attempted to have read into the record a refutation supplied by the People’s Republic of China (PRC), which being excluded from the commission, could not “defend itself against such accusations.”12 FBN Commissioner Anslinger later boasted in US congressional testimony, “I did not permit the Russian delegate to read the Chinese propaganda in the meeting. I called him on a point of order.” Anslinger contested allegations of “the use of gas and bacteriological warfare by American troops,” and the Soviet contention that when speaking of heroin, “under the barbarous conditions of United States warfare—including the blockading of Communist China—no smuggling in or out of China was possible unless conducted by the Americans.” This back and forth over the warring powers’ interest in controlling an array of scientifically synthesized substances, including narcotic drugs, became an attention-grabbing aspect of Cold War conflict. As control of chemical and biological entities became increasingly central to superpower rivalry, politically volatile debates joined market and military power to mimic the magic wrought by laboratories: one’s medicine became another’s poison as the celebrated potential of drugs also made them fearful weapons of war. For US officials involved in policing the domestic drug economy, as Anslinger explained, there “is a good answer to their charge of bacteriological warfare, because we can show that it is chemical (heroin) warfare which is being carried on.”13

Cold War conflict brought to the fore the power of natural and synthetic compounds to wreak havoc, whether overtly deployed as part of a military arsenal or covertly used to infect the social order and undermine military discipline of enemy nations. Simultaneously, these substances became increasingly valued for their potential to advance health and national prosperity. The physical substances deployed in chemical or bacteriological (or even atomic) warfare were distinct and varied; however, there was a widespread belief in both the promise and peril of technological innovation for human health and disease at mid-century. Bacteriological and chemical warfare had been deployed to devastating ends during World War II. While Nazi experiments have received much attention, the Japanese Imperial Army’s Unit 731, led by physician and Lieutenant General Ishii Shiro, also experimented with human subjects to develop and spread biological warfare agents in China. As Ishii later testified to US interrogators, “bacterial bombs had been made and tested and rather sophisticated efforts made to breed and employ disease vectors as well.”14 On the Allied side, the United States dropped incendiary bombs filled with magnesium and napalm, which “caused more widespread devastation in Japan than the atomic bomb.” As historian Ruth Rogaski chillingly assesses these policies, “Japanese citizens, like vermin, perished through the application of chemical technologies.”15 The charges of narcotics drug warfare also pertained. The US Army accused the Japanese during World War II of war crimes for peddling drugs in conquered territories.16 Citing information supplied by the United States, the CND announced it was “profoundly shocked by the fact that the Japanese occupation authorities in Northeastern China utilized narcotic drugs during the recent war for the purpose of undermining the resistance and impairing the physical and mental well-being of the Chinese people.” The UN narcotics body recommended to ECOSOC, “that the use of narcotics as an instrument of committing a crime of this nature be covered by the proposed Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of Genocide.”17

This back and forth augured the increasing centrality of drugs to contests over power in the decades following WWII. In fact it was the well-publicized US refusal to prosecute Lieutenant General Ishii at the Tokyo war crimes trials, in the interests of capitalizing on his research for the US government’s own biological warfare research program, which stoked Chinese suspicion that the United States was deploying bacteriological weapons in the Korean War.18 The conflict escalated to the point of becoming, according to the US Army Center of Military History, “among the more remarkable episodes of the Korean War” when “North Korea, China, and ultimately the Soviet Union [attempted] to convince their own citizens and mankind at large that the United States was engaged in biological warfare (BW). Then and later American officials denied the charge and accused the Communist states of embarking on a propaganda campaign in an attempt to conceal their inability to control actual epidemics. The debate played a prominent part in the ideological struggle for world opinion that accompanied the fighting.”19

Drugs were powerful tools in modern warfare and the specter of the deliberate spreading of disease, the potential “inability to control actual epidemics,” was accompanied by public campaigns to reassure populations of their governments’ preparedness. The US government contended with these issues in part through promoting pharmaceutical industry experimentation with concoctions that could be used as weapons or alleviators of deliberately spread devastation, whether biological or chemical. George W. Merck, as the head of the government’s biological warfare unit during World War II, described the nebulous line between “biological and chemical agents” that might be used to attack humans or crops, and could “prove of great value” to agricultural development, public health, and preparedness in case of postwar attack.20 The US countercharge that infection spread from Communist states’ “inability to control actual epidemics” rather than US biological warfare attacks, whether accurate or not, did demonstrate the new significance of drugs to national security. While there has been much disagreement over the legitimacy of biological warfare accusations, the belief in their accuracy fueled the massive expansion of vaccination and public health campaigns in China, Korea, and the United States.21 US newspapers broadcast the possibility that the Korean War “situation might be considered by the Soviets as a good one in which to stage a trial of such a weapon” and reassured the public that “mass immunization . . . is one of the weapons we are actively forging against germ warfare.” Science News Letter described the interest of “scientists and pharmaceutical manufacturers” in US nationwide polio vaccination trials in 1954 “as practice for what might have to be done if BW is ever let loose on the land.”22

This early 1950s US fear of future Communist biological warfare was accompanied in public accounts by a belief in the already immediate dangers posed by “chemical (heroin) warfare.” As the New York Times suggested in an editorial in 1953, the perception was widespread that Communist China was capitalizing on the revenue derived from the illicit sale of opium while also using “narcotic addiction as a weapon against the societies in which it can get a foothold”: “Opium as a secret weapon is considerably older than the Communist hullabaloo about bacteriological warfare. . . . This is not the time for timidity and soft words. . . . When we get the next bit of nonsense about [US] bacterial warfare the retort should be the documented charge against the Soviet Union and its puppets concerning something that is more deadly and that does not happen to be imaginary.”

In a portrayal of the culpability of drug users in helping fund the nation’s enemies (a tactic that became common to US antidrug campaigns through the early twenty-first century), the paper decried Communist strategy “when teen-age addicts in New York are helping to pay for the shells that kill American boys in Korea.”23 Similarly a Los Angeles police sergeant entitled a chapter of his memoir, “Dope Versus the Atom Bomb,” implicitly contrasting “free world” arsenals to those of “Communist saboteurs,” as he declared, “Red China is engaging ‘warfare by dope’,” infecting US teenagers to “undermine the moral strength of the nation.”24 Such interpretations illuminate how the narrative of criminal drug deployments shifted with the ebb and flow of diplomatic alliances. Until recently China had been the widely acknowledged victim of drug warfare dating back to European encroachment and the opium wars of the nineteenth century, culminating in the Japanese invasion during WWII. Cold War politics radically transformed this narrative in the wake of the US occupation of Japan and in response to the Chinese Revolution of 1949. Suddenly the United States recast the Chinese as purveyors of addiction, and Japan (as an occupied ally, rather than Axis enemy recently accused of peddling drugs as a wartime atrocity) joined the United States as victims of the nefarious drug warfare of Chinese Communists. In a “reverse irony” not lost on some members of Congress, US officials accused “Chinese Communists” of “a fantastic plot to ruin the US armies in Korea and Japan through the cheap peddling of heroin.”25

COLD WAR IMPERIALISM AND THE UNITED NATIONS

Anslinger, as head of the FBN, strategically deployed drug warfare allegations to influence drug control policy at both the national and international levels, particularly with regard to his championing of international passage and national ratification of the 1953 Protocol for Limiting and Regulating the Cultivation of the Poppy Plant, the Production of, International and Wholesale Trade in, and Use of Opium (the Protocol). Described by William McAllister as the “high tide of the original drug-control impetus,” the Protocol brought together the harsher aspects of US narcotics regulatory efforts, extending them to opium producing countries.26 With the two primary coca producing countries already collaborating to varying degrees with the drug control regime, Anslinger sought to extend its reach beyond the Western Hemisphere. The ongoing focus on securing the production and distribution of raw materials took on global proportions and might be viewed as a proving ground for the reach of US imperial ambitions in the midst of the decline of the European colonial empires. Politicized accusations of dope peddling unfolded in a global context where an East–West rivalry between capitalism and communism increasingly filtered through disparities in wealth and power between the industrial and nonindustrial world, and where a North–South divide was being transformed by widespread upheaval as colonized yellow, brown, and black peoples challenged and overthrew white colonial power. Exemplifying this dynamic, when Anslinger appeared before the Senate Subcommittee on Foreign Relations advocating US ratification of the Protocol, the chairman of the committee depicted the global nature of the problem: “And we, of course, are well aware that North Korea, or the Chinese in North Korea, simply have been the satellites of the Kremlin. Now, is there any place where the Kremlin has penetrated elsewhere, Guatemala or any of the other places that they have utilized the drug that you know of—[?]”27

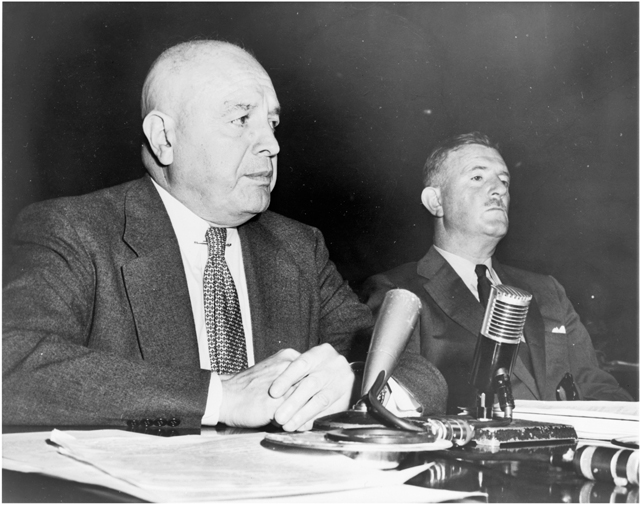

FIGURE 11. Harry J. Anslinger testifying before the US Senate Foreign Relations Committee, 1954. [Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, reproduction number, LC-USZ62–120804.]

Acknowledging a hierarchy of proxy control, North Korea by the Chinese and the Chinese by the Kremlin, Anslinger denied direct knowledge of the scope of Soviet penetration around the globe. Yet, the image of the Kremlin’s covert influence over “satellites” or “puppets” in relation to political subversion or, as with the earlier-described Mau Mau, fostering drug-induced rebellion, provided an ideological framework that at once represented the Third World as dangerously malleable, even unfit for self-government, while providing the rationale for US imperial expansion. Just twenty days before this testimony a US-backed military coup had successfully ousted the democratically elected government of Guatemala.

While drug control was only one ideological and institutional weapon in the Cold War arsenal, following these efforts does provide a perspective on the forces propelling the larger struggle for global influence. The Protocol incorporated many of the provisions of previous treaties and was designed to consolidate them under one instrument with escalated powers of enforcement.28 It limited raw opium production to seven states (a “closed list” including Bulgaria, Greece, India, Iran, Turkey, the USSR, and Yugoslavia) and limited purchases of drugs exported from these states based on national estimates of legitimate demand—estimates that would be set even for states not party to the convention. This was arguably an imperial effort to meet (and regulate), as Anslinger described, “the medical needs of the world” by targeting source, or supply-side, countries as the foundational tenet of drug control, and limiting the scale of the trade according to Western definitions of medical value.29 Along with the power to effect on-site inspections, any state “impeding the effective administration” of the Protocol could be subject to embargo.30 The treaty purported to introduce “the most stringent drug-control provisions yet embodied in international law.” It extended reporting provisions to raw opium and, in a “victory for Anslinger,” stipulated that opium be “restricted to medical and scientific needs,” a definition with built-in exemptions whereby “in a manufacturing country like the United States” military stocks were excluded from the estimate.31 Three of the seven Protocol-identified legitimate world suppliers of raw opium had to ratify the convention before it came into force, an event that did not happen until 1963 in the midst of heated UN debates over whether the Protocol or an alternative agreement known as the 1961 Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs (the Single Convention) should dictate international control efforts.

The Protocol embodied the core prohibitionist principles embraced by the United States, and, in the words of David R. Bewley-Taylor, “was symbolic of US prominence within the UN control framework.”32 The USSR refused to participate in the proceedings regarding the Protocol. Instead, Soviet officials threw their weight (with the support of many former colonial countries) behind efforts to devise another instrument, ultimately realized as the Single Convention, which slightly weakened, although did not fundamentally transform, the control model advanced in the Protocol. The decade-long process of unifying existing international drug control law under a single convention culminated in a standoff between Anslinger’s reluctance to weaken any provisions proposed by the Protocol and the ultimately more widely accepted Single Convention.33 Amidst superpower wrangling, drug control provided a platform for Cold War campaigning. Competing power blocks, largely aligned with the drug manufacturing countries on one side and drug raw material exporting countries on the other, negotiated to advance their own interests.

Anslinger, through some wily diplomatic maneuvering in the midst of negotiations over the terms of the Single Convention, succeeded in using economic and political pressures to have the necessary number of three opium-producing countries ratify the Protocol, which accordingly went into effect in March 1963. Anslinger wrongly hoped this would undermine the Single Convention, which went on to receive the necessary number of ratifications (Kenya provided the critical fortieth accession) and went into effect in December 1964. Once ratified, the Single Convention superseded the Protocol as the prime instrument of international drug control. Despite Anslinger’s initial chagrin, by the end of the decade he was urging Congress to ratify the Single Convention as an effective international enforcement tool, which it did in 1967.34 There were differences between the two treaties, yet both entrenched the fundamental tenets of supply-side control and, as a US Public Health Service officer explained, the Single Convention “continue[d] essentially the previous international controls restricting production, distribution and use of narcotics drugs to medical and scientific purposes.”35 Moreover, in a triumph for a central principle of drug control, long advocated by Anslinger himself, US prohibitions against marijuana consumption (first introduced in national legislation in 1937), and any other nonmedical consumption of organic raw materials (coca, opium), were solidified in the international treaty. The final outcome ultimately reflected “US dominance in the UN control system [and] ensured that the Single Convention created a Western-oriented prohibitive framework for international drug control.”36 However, the initial standoff at the United Nations over the US representative’s support for the Protocol and Soviet support for the Single Convention shows how a new geopolitical context infused drug regulatory conflicts with symbolic power.

Soviet strategy was to align with Third World countries (including many producer states that saw the Single Convention as the lesser of two evils, and as an opportunity to push back against some of the more onerous drug regulatory provisions emanating from the industrial world) and to publicly challenge the considerable US influence at the United Nations where it initially enjoyed a voting-bloc majority.37 Debates about the mechanisms necessary to institutionalize drug control must be understood in relation to the anticolonial revolutions of the era. The United Nations, in and beyond the CND, had rapidly become a forum for US and Soviet denunciations of each other’s imperial ambitions. Soviet representatives depicted US initiatives as a replacement for European colonial control, and the United States countered with accusations focused on the Kremlin’s alleged expansionist designs. The US delegation to the United Nations reported, “Increasingly, both the United States and the Soviet Union are coming to see that the outcome of their struggle may be determined largely by what happens in the uncommitted nations,” as debates over sovereignty unfolded concurrent with efforts to regulate the international drug marketplace.38 In the first decade of the UN’s existence, the USSR could only level symbolic challenges to US domination. The US ability to gain passage of the Protocol occurred in a context where the “Soviet bloc” was excluded from “all committees established to deal with colonial disputes.” The United States, on the other hand, as one contemporary observer explained, “has been deeply involved in most aspects of the UN’s work concerning colonialism, and it has been extremely influential.”39 Mobilizations for political independence confronted contested international models for economic development when “the colonial powers and their allies and associates retained a very strong position in the UN” and as the Cold War facilitated the transition of these allies into an international anticommunist bloc.40 US influence at the United Nations offered a welcome framework to “avoid drifting in the dangerous currents of colonial rebellion,” as one contemporary international relations scholar explained, “filtering an act of intervention in colonial affairs through an international organization may transform what would otherwise have been labeled ‘an imperialistic act’ into an action recognized on every side as necessary and fair to all parties.”41

Chapter XI, article 73, of the UN Charter recognized the principle of equal rights and self-determination of all peoples, ensuring the international body became a forum where the implications of these terms were debated. This was reinforced in 1952 with the passage of Resolution 637 (VII), reiterating “The Right of Peoples and Nations to Self-Determination.”42 The United Nations included thirty-five member states in 1946; by 1970 national decolonization movements swelled that number to 127 member states. As the march of successful independence movements began to shift the balance of power in the United Nations across the decade, the United States consistently voted with other colonial powers to resist intervention in what they viewed as “domestic” disputes that came before the Security and Trusteeship Councils (which had jurisdiction over colonial and trust-territory issues respectively).43 There were a number of factors influencing the US position. While the United States increasingly used economic and political pressure to exert influence, with drug control just one prominent example, the country continued to have both colonies and trust territories under its jurisdiction.44 It is worth noting that the lack of representational government in places like Puerto Rico and the Trust Territories of the Pacific made them particularly valuable sites for conducting tests of the new atomic, chemical, and biological weapons so critical to US Cold War arsenals. US economic and military alliances with European powers also militated against stances embracing anticolonial positions. While the United States ostensibly opposed imperialism in the name of democracy and the right to self-determination, such “principled U.S. positions were tempered by having to deal with the ongoing economic weakness of their European allies.” Furthermore, anticolonial movements often challenged the terms of foreign investment which placed the United States on the defensive, as did the resulting perception that they fostered instability and threatened the establishment of US military bases (a key component of its Cold War strategy). As historian Henry Heller argues, “anticolonialism was one thing, but opposition to economic imperialism by third world leaders was quite another matter so far as Washington was concerned.”45 Finally, with the USSR assuming the role of “most outspoken critics of colonialism at the United Nations,” US foreign policy became driven by anticommunism, a priority that often necessitated procolonial politics.46 The US representative on the Trusteeship Council, Mason Sears, explained this prophylactic vision, “We ensure freedom tomorrow by blocking Communism today.”47 This diplomatic maneuvering was widely perceived as the superpower struggle that it was. US delegates reported back to the Senate Committee on Foreign Relations that an emerging Afro-Asian bloc “wish[es] to keep ‘colonialism’ from being a ‘cold war’ issue. The Asian and African countries do not wish to give these European powers a chance to hide behind an attack on Soviet Imperialism and thus perhaps divert attention from their duty to promote self-determination pursuant to article 73 of the charter.”48

The United States used its disproportionate power to influence struggles defining and asserting self-determination. In 1952, for example, after most of the leadership of the nationalist forces had been killed or imprisoned, a constitutional convention established Puerto Rico as a US Commonwealth. Recognized by the United Nations, Puerto Rico’s status constituted a new category apart from the original interpretive framework outlined in the UN Charter, having ended colonial rule in a manner that “involved neither full independence nor full integration.” Puerto Rico’s semi-independent status became a model for European colonial territories such as Suriname, the Netherlands Antilles, and French Togoland among others.49 In terms of recognizing the power of newly independent states, the United States also played an important role in determining the international balance of power. Responding to growing domestic resentment over US expenditures on the United Nations, US officials “conceded that on an ability-to-pay basis we would owe in the neighborhood of 38 percent, but averred, in effect, that other states had better start showing some sense of sharing the burden.” The General Assembly “grudgingly” accepted in 1957 that “no state should pay more than 30 percent of the budget.”50 It was demonstrated at the time that relative to GNP the US payment was in fact “abnormally small” and that across the 1950s the “less-developed states” increased their contributions far more rapidly than the developed states, with African states in the period from 1946–69 contributing the most in relative terms.51 Nevertheless, the absolute value of the US contribution fueled US congressional disillusionment with the United Nations, particularly when votes did not go its way. In what might be seen as an updated version of nineteenth-century Euro-American paternalists chafing at the burdens of colonial administration, small states were accused of not paying their “share” in discussions over how to apportion representation in this international forum. Sovereign equality did not imply economic equality and, at least in terms of international governance, US representatives believed all states were not in fact equal.52

While the General Assembly could not dictate policy with the force of the veto-empowered Security Council (whose five members were the victorious Allies in WWII: the United States, United Kingdom, Soviet Union, China, and France), as an international public forum that included representatives from all UN member states it did exert considerable political and symbolic influence. By 1960 state membership at the United Nations soared to 114 states, and the new members, all former colonies (35 from Africa, 15 from Asia, 11 from the Middle East, and 2 from the Caribbean), constituted a solid two-thirds majority that often garnered support from the Soviet bloc.53 Contests over drug control unfolded in the midst of these revolutionary shifts in power, and fueled US skepticism towards the United Nations. In 1960 Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev launched an opening salvo calling for a UN declaration demanding immediate independence for all non-self-governing countries that ultimately evolved into a more moderate, yet nevertheless significant resolution passed by the General Assembly in December 1960: “The Declaration on the Granting of Independence to Colonial Countries and Peoples.” Calling for the end of all armed action against liberation movements, declaring colonialism a violation of people’s human rights and right to self-determination, and demanding “immediate steps to be taken . . . to transfer all powers to the peoples” of dependent territories, the declaration echoed sentiments first expressed by the non-aligned Afro-Asian world at Bandung, Indonesia, in 1955.54 Despite a moderating clause that stated any attempted “disruption” of the territorial integrity of a country went against the principles of the UN Charter, the major imperial powers (including the United States, the United Kingdom, France, Belgium, and Australia) all abstained. But they could not prevent the resolution’s adoption by the General Assembly.55 A special committee, known as the “Committee of 24,” was established to oversee the declaration’s implementation which, despite its lack of enforcement powers, managed to dominate much of the debate on the floor of the General Assembly across the decade and produced a number of resolutions on behalf of anticolonial forces. According to a former US representative to the Committee of 24, resolutions were “normally . . . worked out by a group of communist members and anti-Western African and Arab States,” often with the support of “Latin American” members who sought a middle ground so as not to alienate US officials. This inability of the United States to mobilize a majority in a context where “self determination is equated with independence” fueled public confrontation over US imperialism, such as when the delegate from revolutionary Cuba denounced US control over Puerto Rico and the US representative resigned from the committee in disgust.56

While the Committee of 24’s work is beyond the scope of this chapter, it is indicative of the ways in which anticolonial movements by the 1960s were forcing the United States to reconsider its approach to international diplomacy, including narcotics control. Only a few months after the General Assembly issued the Declaration on Colonial Independence, the United Nations circulated the 1961 Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs for ratification. Describing the convention as a Soviet ploy to win anticolonial alliances, FBN Commissioner Anslinger initially advocated against US ratification, although with the sufficient support of other states it went into effect in December 1964.57 The Single Convention, from Anslinger’s perspective, reflected a Communist victory: a dangerous example of drug policy intersecting with Cold War and anticolonial politics. When Anslinger argued before Congress against ratification he characterized the elimination of the closed list of raw material–producing states (the major distinction behind his preference for the Protocol over the Single Convention) in stark terms:

The Soviet bloc took the bit in its teeth with the assistance of the neutrals and the newer African nations emerging into independence, by holding out the idea that they might be able to participate in this legitimate traffic. . . . The Soviet bloc even held out the proposition to the African nations, “You vote with us and you can produce opium.” That was not the worst of it. . . . The Soviet bloc made reservations as to the countries not there for political reasons. . . . I think Communist China forced the Russians into this position . . . the Russians felt the people who were not there should not be bound. . . . The Communist Chinese were always complaining about the fact Formosa was making the estimate for all these people. . . . What they are trying to do with these reservations, they are trying to break out of this tight control.58

In this dramatic accounting, Anslinger tapped into sentiments that held widespread appeal, reorienting conflicts over access to participation in the global drug economy toward questions of political legitimacy.59 Drug control as Cold War conflict marginalized the Third World challenge to the dictates of the industrial world, deploying a logic—embraced to a certain extent by both the United States and the USSR—whereby the alleged immaturity of the “neutrals and the newer African nations” made them vulnerable to bribery and political manipulation. US Congressman John R. Pillion (NY) responded by urging newspapers and television media to “publish [Anslinger’s] recital” about the Single Convention in order “to prove to the world that the Communist Soviet apparatus is primarily responsible for this proposed United Nations action.” He lamented the “consolidation of political voting power shifting from the United States and the free world into the control and direction of the Communists in the Sino-Soviet bloc.”60 In a context where the United States lined up with other colonial powers to contain the implications of “self-determination,” the fervent invocations of the need for US-guided drug control to protect “free nations” reflected Cold War competition and the anticolonial challenge to US dominance at the United Nations. The primary architect of the international treaty, Adolph Lande, was a US international civil servant, Anslinger’s close friend and confidant in the UN secretariat overseeing narcotic drugs, and by the early 1970s a representative of the American Pharmaceutical Manufacturers’ Association, echoed these concerns. At the United Nations Lande lamented challenges to US dictates, which he couched in racist assertions of cultural superiority when he worried that “the UN drug control apparatus was being staffed increasingly by non-Westerners,” and complained that their frequent opposition to the US prohibitionary stance was due to their “low intellectual level” and “violent anti-Americanism,” especially among Africans.61

Despite this (mostly symbolic and revealing) furor, the Single Convention consolidated into one treaty drug control mechanisms that had worked and would continue to work to US advantage. It incorporated the basic tenets of drug control that had been promoted by the United States since World War II: it institutionalized inequalities between the industrial and nonindustrial world, oriented control toward raw material–producing states, and privileged a capitalist international economic framework as the guiding principle behind it. By 1967, with Anslinger’s approval, the US government ratified the Single Convention to ensure, in the words of President Lyndon B. Johnson, the country continued to play a “leading part in international cooperation for the control of narcotic drugs.”62 For all the heated US-Soviet posturing, the drug control regime weighed most heavily on Third World and producing nations. The newly consolidated regime extended international efforts to control the production and circulation of raw materials backed by two key principles. First, it called for the main manufacturing countries, mostly colonial powers (including the United States, England, France, Germany, Switzerland, and Holland), to fulfill their obligations to the control regime by limiting drug output to global “legitimate” needs. As Anslinger explained the new thrust of the drug control regime, “Today, every one of those countries is fulfilling those obligations in relation to manufacturing. So instead of the manufacturing countries being the culprits today, it is the producing countries.” This then led to the second guiding tenet: that countries in the industrial world were “the principal victims of overproduction.”63 Even while industrial world laboratories churned out drugs on an unprecedented scale, the logic of drug control emphasized the need to control production in the nonindustrial world, embedding within it a new imperial framework for securing hierarchical economic flows, while invoking victimization to legitimize the extension of First World police oversight.

These were the substantive stakes behind disagreements described earlier over the seating of the Chinese Representative at the United Nations. Due to its ongoing support from the United States, the exiled and defeated Chinese nationalist government in Formosa (Taiwan) represented all of China at the United Nations, meaning it was responsible for submitting estimates on drug requirements for the continent ruled by the PRC. These estimates formed the basis for judgment on compliance and potential sanctions. This was why the PRC was “always complaining” that it was bound by drug-needs statistics submitted by a hostile regime. Political affiliations clearly influenced designations of legality and “legitimate” participation in the international drug trade. Since the PRC government was not granted political recognition, it had been denied a “legitimate” role in negotiating the drug market. As historian William O. Walker describes, Anslinger diligently sought to “cast the Chinese as international outlaws on the subject of opium.”64 When the Chinese government legally tried to sell stocks of opium, which had been seized from factories run by Japanese occupation forces during World War II, the US-led Western economic embargo against Communist China ensured its exclusion from the legal market. As Anslinger said, “They offered that legitimately, but no country would take it on.”65 While scholars have pointed to the lack of evidence behind heated accusations of illicit Communist dope pushing during the Cold War, they have tended to overlook the fact that by virtue of Communist exclusion from the narcotic drug market, any opium the PRC might produce for export was predestined for illegality according to the logic and regulations advanced by the international drug control regime.66 Drug control in this context offered both an ideological framework for challenging the readiness of colonized peoples for self-determination, limiting the economic and political power of Communist countries, while structuring participation and designating legality within the marketplace according to the interests of capitalist countries.

POLICING THE CRISIS

Cold War posturing and colonial conflict animated tensions at the United Nations in debates over competing visions for international drug control. These international dynamics also shaped US national drug policy, informing people’s beliefs about the threat posed by narcotics and people who consumed or trafficked in them. Fears of communism and racially inflected ideas about self-determination filtered into and fueled domestic anxieties producing a veritable “moral panic” in the 1950s about drug crimes. Stuart Hall and colleagues detailed how such panics are social phenomena and are “about other things than crime per se” when he detailed how the heady mix of race, youth, and crime became an ideological conduit for the widespread belief in Britain in the 1970s that the social order was disintegrating and “slipping into a certain kind of crisis,” which generated in turn an authoritarian consensus around the need for “law and order.” Two decades earlier, the United States was gripped by a similar sense of crisis with analogous ideological underpinnings that sparked a crackdown on drug “crimes.” The social construction of these crimes, the way they were understood and defined, as well as the social forces that were constrained or contained by, or benefited from, them, are essential for understanding the origins and underpinnings of the subsequent decades-long US “war on drugs.”67

As people lined up before Congress to testify in support of US ratification of the 1953 Protocol, the chair of the Senate Subcommittee of the Committee on Foreign Relations deployed a paranoid discourse increasingly common to Cold War public culture:68

First, if our American people can be made aware of the fact that Mao Tze-Tung is engaged in undermining the health and the morale and the strength of our boys in the services, and secondly, if they can get, as you say, a picture of this dirty business, that it is not just a few skunks around the corner that are handling it, but that it is the result of people in high places, like Mao Tze-Tung, who is using it [opium] as a weapon to deteriorate the morale and health of this country, then the people of this country will become aware that we have to “stop, look, and listen” and think about it.69

The Chair of the Committee on Foreign Relations, Alexander Wiley, warned the “American people” of subversion lurking in their midst, advising that they “stop, look, and listen” and be on guard against drugs being used as a weapon to attack “this country.” He invoked international enemies to call for internal vigilance and policing. A parade of witnesses echoed these sentiments, with a journalist testifying that “dope warfare” was an “instrument of policy with Red China,” followed by a New York City Police Department inspector, the president of pharmaceutical giant Merck & Co., Inc., and the Secretary of State for UN Affairs, all warning of the dire need for aggressive drug controls. Mrs. Duncan O’Brien of the New York Federation of Women’s Clubs cut to the chase: “Our Communist enemy has invaded. They are shooting our youth with drugs instead of bullets.”70 As the United States promoted its drug regulatory vision internationally, such images were mobilized in the 1950s behind the passage of extraordinary legislation that vastly expanded domestic police powers. In a decade marked by dramatic conflict over racial equality and civil rights, the social panic and attack on drug “crimes” could be used to recast dissent and nonconformity as dangerous “contagions” threatening the very fabric of American society—rhetoric grounded in the power of modern drug technologies and public health concerns regarding the spread of disease.71

Religious leaders, the media, teachers’ organizations, youth congresses, and state and local officials all echoed congressional fears that the “drug cancer operating among troops of the United Nations in Korea” was only one site of a broader illness infecting US society: “Red treasuries swell as free world consumption of drugs mounts. The social aspect of the menace is evident in its degenerating effects upon our youth, here at home.”72 Cardinal Archbishop Francis Spellman and evangelist Billy Graham both visited US soldiers in Korea and decried the “frightfully high number” of narcotic addicts among them.73 Journalists sought out firsthand testimony at places like the Stateville-Joliet prison in Illinois where almost half the inmates were veterans, the majority “Negroes,” and a significant minority “admitted addicts.” One Korean war veteran at Joliet, “who shall be called James, a Chicago negro, 26,” when interviewed explained, “I believe the Chinese Reds are to blame for making ‘junk’ so cheap and easy to get. . . . It’s one way to undermine the enemy soldiers. A lot of my friends thought so too, but we kept on using it.”74 The acknowledgment of enemy treachery raises interesting questions as to the private, political, or other reasons soldiers “kept on using it,” but for readers of the Daily Defender, the story ended there. Appealing to a similar curiosity, the New York Times tracked the number of soldiers sentenced and discharged “on narcotics charges.”75 The FBN reassured the public it was working to contain the threat returnee soldiers might pose by getting “the Army to notify the chiefs of police, where the boys return to their home communities, so that they do not become sources of infection and start peddling.”76

Depicting veterans as potential “sources of infection” was indicative of a broader tendency to link (illicit) drug consumption with the potential for criminal delinquency. There emerged a widely remarked-upon relationship between drugs, delinquency, racial identity, and social pathology. As one NYC prosecutor explained, “addiction, then, is a disease of high social contagion that not only may produce criminality . . . but also tends to attack those persons whose resistance to anti-social activity is, for a multitude of reasons, notoriously low.” He tellingly left it to “psychiatrists and sociologists” to explain its high incidence “among the negroes and Puerto Rican” youth.77 A Times Youth Forum meeting in Los Angeles on how to “improve the welfare of youth in the United States” illustrated the reach of this emerging consensus. Teenagers aired their belief that without a “happy home,” spiritual and vocational guidance, and good role models, “Communism will be used to fill in the gaps, narcotics to numb the sting of discouragement and delinquency as the counterweapon to fight the world.”78 The director of Chicago’s Crime Prevention Bureau, Dr. Lois L. Higgins, warned an audience at the National Biology Teachers’ Association: “While we join other free nations to resist the threat of Communism in other parts of the world, our Communist enemies are waging a deadly and tragically successful war against us here at home. Narcotic drugs are some of the weapons they are using with devastating effect.”79 At a health fair in Chicago, Higgins simplified this message: “Youthful narcotics addiction is one facet of the hydra-headed threat of crime and communism.”80 The image of corrupting forces threatening American youth was deeply embedded in the racial politics of the era. A 1956 article in Reader’s Digest entitled “We Must Stop the Crime that Breeds Crime!” warned readers: “Formerly concentrated in the Negro, Puerto Rican, Mexican and Chinese sections of a few large cities, addiction has spread during the last ten years to smaller metropolitan areas and taken in youths of every race.”81

Drug control in this context recast domestic upheavals as foreign infiltration while elaborating a strengthened system of social control and policing that particularly targeted African American, poor, and immigrant communities. It eschewed the language of race with a seemingly neutral and socially beneficial discourse of protecting (white) “youth” against criminal contagion.

Jacquelyn Dowd Hall describes that by the early Cold War, “antifascism and anticolonialism had already internationalized the race issue and, by linking the fate of African Americans to that of oppressed people everywhere, had given their cause transcendent meaning. Anticommunism, on the other hand, stifled the social democratic impulses . . . narrow[ing] the ideological ground on which civil rights activists could stand.”82 Much as red-baiting sought to sever black American political mobilizations from the international context out of which they came, so too did accusations of criminality. The Ku Klux Klan attacked integration as communist-inspired and attacked acts of civil disobedience as amoral flaunting of the law. A full decade before presidential candidates like Barry Goldwater and Richard Nixon would run on political platforms invoking “law and order” as a not-so-veiled appeal to white supremacist resentment towards black civil rights, a “rhetoric linking crime and race” had already become “fused in the public mind.”83 While officials distanced themselves from the position that crime was caused by biological or racial factors, the social sciences provided a seemingly race-neutral framework for explaining the preponderance of crime among certain racial groups. This slippage was a critical component of a new large-scale policing and prison system that grew in tandem with the victories of the civil rights movement. Appealing to fears of contagious subversion, law enforcement measures worked to recast cultural, racial, and political manifestations as criminal threats to public safety. Scientific presumption that pathology caused crime functioned as a mechanism for perpetuating the politics of Jim Crow segregation, denial of political rights, and the maintenance of economic inequality within a liberal articulation that elided its white supremacist foundations. This was nowhere clearer than in the manufactured drug crisis that led to unprecedented policing, escalation of criminal penalties, and the targeting of poor, immigrant, and especially black communities during the 1950s.

Drugs and war fused in domestic politics as the public and government responded fiercely to sensational portrayals of the “narcotics menace,” and as the FBN successfully linked projects of international and domestic drug control. By the 1960s, congressmen celebrated Commissioner Anslinger as “the No. 1 American general in this fight against narcotics addiction in our United States,” along with the new “legislative weapons necessary to win this war.”84 Just a decade earlier, when the Welfare Council of the City of New York pursued an investigation “for the purpose of determining the nature and extent of ‘teen-age’ drug addiction in New York City,” the purported crisis of “teen-age” addiction was not common knowledge: “The project committee encountered difficulty in obtaining statistics from public agencies and soon discovered that most public agencies have not kept very close check of the incidents of ‘teen-age’ addiction. This failure was principally due to the fact that there was no such awareness on the part of most public agencies of the existence of such a situation.”85

A spate of local and national hearings and investigations helped raise “awareness” of the alleged crisis as part of an effort spearheaded by the FBN and fulfilled by Congress to revise the nation’s drug laws. Sensational media coverage fueled public uproar. As Newsweek reported in June 1951, “Last week the verbatim confessions of teen-age addicts filled up more newspaper columns than the MacArthur hearings.” Such youth testimonials of arrest for using “marijuana, heroin, morphine, or cocaine” underwrote the buildup to legislative action.86 By 1951, the crisis inspired radical proposals: “Recent disclosures of teen-age addiction may result in the passage of more stringent laws. Already there are demands for legislation which will make the sale of narcotics to minors punishable by death.”87 When a congressional committee held hearings that year to revise narcotics legislation, the chairman declared, “A drug addict is something more than a criminal. Because he is enslaved to dope he is, in a sense, also a ‘disease’ spreader. . . . Because their moral fiber has been destroyed, victims of dope, like victims of smallpox, must be quarantined for their own protection and for the protection of the rest of society.”88 The fear of an “epidemic of narcotic addiction among younger people” had a profound impact on national drug policy.89

Between 1951 and 1956, as historian John C. McWilliams notes, there was “a dramatic increase in the number of Washington legislators who proposed federal statutes for the greater control of narcotics,” with twenty-six bills presented in 1951 alone. The passage of the Boggs Act in 1951 introduced mandatory minimum sentences for narcotics law violations as well as a number of measures to “make it easier for prosecuting attorneys to secure convictions.”90 A radical law enforcement tool, the mandatory minimum sentence undermined judicial discretionary power and rapidly “more than doubled the average prison sentence of federal narcotics offenders.”91 Even prior to the Boggs Act, the FBN boasted that with only 2 percent of “Federal criminal law enforcement personnel,” bureau arrests accounted for “more than 10 percent of the persons committed to Federal penal institutions.”92 Between 1946 and 1950, a 20 percent decrease in people sentenced to federal prisons was accompanied by a 20 percent increase in those “sentenced for narcotic violations.”93 Five years later the Narcotics Control Act in 1956 once again escalated penalties dramatically. Selling narcotics to juveniles now carried “a maximum sentence of death upon recommendation of the jury,” and the act maintained mandatory minimum sentences, while extending their maximum duration: “For the first possession offense, the penalty was two to ten years’ imprisonment with probation or parole. For the second possession or first selling offense, there was a mandatory five to twenty years with no probation or parole; and, for the third possession or second selling and subsequent offense, the violator was sentenced to a mandatory term of ten to forty years with no probation or parole.”94

State laws largely mirrored the regulations adopted at the national level, with some dissent. In 1958, Missouri lowered penalties for a first-time drug conviction since, as the circuit attorney in St. Louis explained, “We found that juries simply would not send a man up for two years on the strength of a marijuana cigarette found in his possession.” Yet this incident, according to a journalist for the Nation, “marked the rare occasion when an agency of any government questioned the authority or wisdom of Anslinger” (who, it might be noted, quickly retaliated by withdrawing the bulk of FBN officers from the state).95

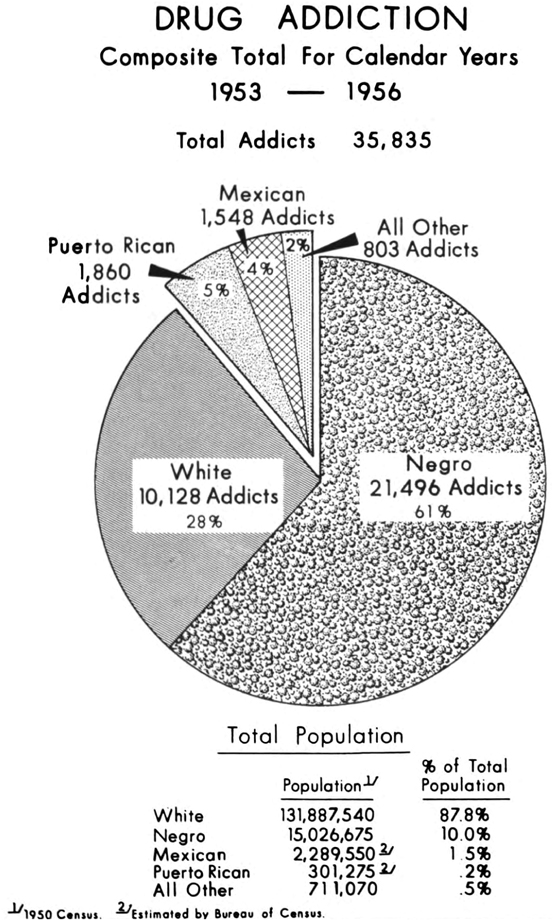

The escalation of penalties for illicit drug consumption had deeper roots than the sensational coverage that directly preceded the passage of legislation.96 While congressional testimony and media coverage seemed to confirm a popular demand for action, the FBN itself was a critical force cultivating the perception of a crisis. Statistics regarding the national incidence of addiction were based upon police reporting of arrests for narcotics law violations. All persons arrested for illicit narcotics possession were classified as “addicts,” and the increased number of arrests created the perception of an increasing incidence of criminality. As enforcement—and reporting—escalated, so too did the incidence of crime, leading in a circular fashion to the perceived need for more policing. In the wake of public hearings on addiction in New York in 1951, “the size of the Narcotics Squad was doubled.”97 With the passage of the Boggs Act in 1951 and the Narcotics Control Act in 1956, the FBN received the two largest budget increases in its history.98 The expansion of police powers was also connected to the presumed race of narcotics law violators. The FBN targeted “the teen-age problem [that] is in New York, Chicago, and Los Angeles” and focused most of its policing in the predominantly poor and black neighborhoods of those cities.99 As a consequence, throughout the decade, charts submitted to Congress to justify narcotics enforcement budgets reinforced the association connecting minorities, addiction, and crime.

In an era when the explicit deployment of race as an explanation for social inequality became increasingly unpalatable, congressmen delicately pointed to the overrepresentation of black “addicts” in FBN reports. A year after the passage of the Narcotics Control Act, Rep. Gordon Canfield (NJ) fretted, “I wonder if it is proper—if I am treading on dangerous ground I hope you will tell me—but I note in your charts presented today that the dope peddlers of the United States apparently prey to a large degree on our Negro population, and that I am sorry to hear.”100 In the midst of mass African-American protests, sit-ins, and marches for economic, political, and social equality, many congressional representatives knew that black people were disproportionately being charged with narcotics violations. It is clear from congressional exchanges that many sought to studiously avoid addressing race directly, even while presuming black criminality. The record of congressional hearings themselves reproduced this avoidance of race, even while it was clearly being given serious weight, as is evident in the notable frequency that conversations about race and drug use proceeded “off the record.” Rep. Otto E. Passman (LA) emblematically exclaimed: “I am not making any racial implications at all, but when you have statistics of this type, then there should be some explanation as to why there are five colored addicts to one white addict.” In response, before going off record, the Commissioner of Narcotics reiterated a frequent explanation that crime was “confined to certain police precincts where you have very bad social and economic conditions,” assuring the Louisiana congressman that “negro” addiction was not a problem in the South (as opposed to the North) —echoing perhaps a frequent assertion that increased levels of freedom for blacks brought increased levels of crime.101

FIGURE 12. Federal Bureau of Narcotics chart representing drug addiction statistics for 1953–1956, differentiated by race.

Such attitudes in the 1950s and 1960s bolstered funding for the FBN, and fueled the dramatic expansion of police powers. The Cold War tendency to pursue national security through international covert operations had a domestic counterpoint in the shift toward undercover narcotics enforcement. As Anslinger explained, “We decided to take advantage of the men and the money and the Boggs Act—we had all three—so we stepped into the underworld. We put most of our new men right out into the underworld.”102 By 1957, the commissioner testified that the vast majority of narcotics agents “work undercover. Even our supervisors, we try to have them work undercover.”103 This shift to undercover work depended on a number of transformations including the FBN need to “recruit Negro, Sicilian, and Chinese agents.”104 Along with changes in police personnel came the weakening of civil rights protections. Early in the decade Anslinger described a New Jersey law as “an excellent thing” for enabling officers to arrest “an addict as a disorderly person just like a common drunkard.” He lamented that in Washington, DC, “there is nothing that the police can do. They do not have the power to pick up a man because he is an addict. They must have probable cause. We have a search-and-seizure restriction in Federal jurisdiction.”105 Voicing a common complaint, police frequently demanded “the right to arrest without warrant; the right to search for and seize contraband before and after a valid arrest.” Without them, since 1950 the police had pursued other tactics to “offset some of these handicaps.” Undercover officers increasingly “shifted enforcement emphasis to the purchase of drugs from violators—a method which is slow, costly and inefficient by previous standards, but designed to avoid judicially imposed disabilities.”106 These tactics tended toward the apprehension of low-level violators. As the new drug policy’s most vociferous public critic, a professor of sociology at Indiana University, Alfred R. Lindesmith, described, “penalties fall mainly upon the victims of the traffic—the addicts—rather than on the dope racketeers.”107 Nevertheless, in 1956 many of these “obstacles” were removed. Anslinger celebrated the introduction of “witness immunity” in narcotics cases, explaining, “We never got this type of an informer who is now willing to trade his long-sentence term for turning in his connections.”108 And the Federal Bureau of Narcotics was “given the authority to carry firearms, serve search warrants, and make arrests without warrants” in their pursuit of narcotics law violations.109

To some contemporaries, the connection between racism, policing, and opposition to black political mobilizations was clear. In a Pulitzer Prize–winning series, reporter Gene Sherman remarked: “The methods of narcotics officers have come under fire lately by some moralists, attorneys and vociferous proponents of civil rights.”110 In a remarkable statement submitted to the newly constituted Federal Civil Rights Commission which the petitioners shared with the Los Angeles Tribune, the “Fellows of Tank 12A-1” of the Los Angeles County Prison protested that narcotics squad police tactics violated their “Constitutional guarantees, railroading men and women to the penitentiary.” Offering an indictment of the powers granted under narcotics legislation, these prisoners suggested their due process rights were violated by the use of secret informers against whom defendants had been denied the right of subpoena. Moreover they argued undercover agents used bribery, in the form of drugs and the promise of reduced sentences, to gain informers’ collaboration, a tactic openly celebrated by the FBN. Explaining that agents deliberately targeted “slum areas” to achieve their “specific goal,” they protested being made “objects for political popularities and gains,” and implored the Civil Rights Commission “to help save what the Constitution guaranteed us.”111 Drug laws were powerful, oppressive tools in a city where the police force “protected its white constituency, [by] keeping in check,” in Police Chief William H. Parker’s words, the “primitive Congolese.”112 This was true across the nation. In striking testimony, Cook County state’s attorney John Gutknecht described the racial politics and legal consequences of narcotics enforcement in his jurisdiction, which included the city of Chicago. Remarking on “the prevalence of Negro defendants among those charged” and noting police operations tended to target people who “operated mainly in the lower/middle branches of the illicit traffic,” the state’s attorney believed: “The white race is responsible for the distribution of narcotics in America, and let’s not kid ourselves. The others are the victims.” The perception that drug enforcement was a tool for maintaining white supremacy, while not popularly embraced, nevertheless seemed to lie just beneath the surface of policy debates. The governor of New Jersey drew upon this reservoir when, in the context of numerous states “passing laws which match or exceed the rigor of the national laws,” he vetoed a narcotic bill passed by the state legislature, “characterizing it as an example of a lynch law.”113

The racial logic behind the expansion of policing drew upon a seemingly apolitical professional consensus forged among sociologists, psychologists, and other experts that identified specific drugs with certain “types of people” and communities. The incredible expansion of new drug commodities propelled a public health debate about the relationship between habit, addiction, crime, and disease, which along with prison demographics, represented economic, racial, and cultural bias even while asserting scientific neutrality. When asked before Congress, “from what strata of society would you say the largest number of addicts come—the low, middle class, or upper crust?” the FBN commissioner replied, “Unquestionably from below. . . . These fellows mostly have been criminals first and then addiction follows. The type of people they live with, that is where you get addiction. You don’t see addiction where the individual has a good school, a good home and a church.”114 Suggesting poverty bred crime along with the absence of “good” schools and homes clearly appealed to the normative power of white middle-class beliefs. The definition of addiction devised by the World Health Organization for international drug control officials, which emphasized not its impact on the individual body but rather the threat that body posed to the broader community, was adapted to social control initiatives in the United States. Dr. Harris Isbell, the director of the Addiction Research Center of the USPHS, and Nathan B. Eddy, his colleague and former member of the WHO’s Expert Committee on Narcotic Drugs, clarified the intent behind the definition of addiction and its relevance for drug control:

It was not meant to be pharmacological, nor strictly speaking scientific, but practical, and was intended to include the diverse substances currently under international narcotics control. State and national narcotics laws and regulations and international narcotics conventions are designed to prevent or at least limit abuse of cocaine and marihuana as well as of opium and the potent analgesics. Though all of these substances are commonly and loosely termed narcotics, their properties differ so widely that they are similar only in being subject to abuse and in creating social dangers.115

This focus on “social dangers” left room for discriminatory application of the law according to subjective representations of what constituted a threat to the dominant social order. This definition led to the targeted policing of specific communities, and enabled the ongoing production, testing, and consumption of drugs by other people. Citing studies conducted on inmates at the USPHS narcotics farms, these scientists warned that the new synthetic drugs varied in their potential to generate addiction and implored a “need for flexibility” so as not to hamper research into a “nonaddicting pain-relieving drug.” They also went on to advise that “the amphetamines, the barbiturates, or other sedatives” not be subject to control since their “clinical experience leads us to believe that most persons will handle and use these drugs as prescribed.”116 These allowances for drugs most widely consumed at the time by white middle-class housewives or teenagers studying for exams speak to social bias. The hoped-for power of the laboratory to create nonaddictive painkillers was paired with the “clinical” belief that some drugs (and by extension, some people) did not pose a social danger.117

Debates about addiction sharply reveal this duality. Embedded in the process of designating legality was the recognition of the power of drugs to effect positive change and to pose threats, a calculus profoundly influenced in any given circumstance by the broader context of cultural, racial, and political conflict. One common fear was the alleged power of drugs to incite people to frenzy and economic depravity, as expressed by Senator Mike Mansfield of Montana: “As I understand it, the drug addicts, once they get into the habit, will do anything to get the drug, and that means of course, they will steal, they will rob, and they will do anything,” to which Anslinger responded, “That is very true, Senator, because they do not work. They just live a life of crime.”118 Such sentiments fueled belief in a drug crisis and sustained fearful enthusiasm for extreme coercive measures. In the words of a federal judge: “What would they do if a man came in bringing tuberculosis germs and infected the public with tuberculosis germs? A person like that should be executed. And yet by bringing narcotics in this country they were bringing in something worse than tuberculosis germs. I think the death sentence would not be an inappropriate sentence.”119 In another example, a prosecutor’s vision neatly contained the productive and destructive potential of drugs in a simple plan: “The plan calls for the hospitalization of addicts on a massive scale . . . some of these . . . might be work camps; others might be on farms . . . others—more immediately available—would be existing institutions, such as mental hospitals with beds that have been emptied through the miracle of tranquilizers and improved therapy, or tuberculosis sanitariums vacated by the new wonder drugs.” A clear line existed in this critic’s mind between the wonder drugs and those producing addiction: In “good conscience” the state “ought not engage in administering narcotic drugs to individuals for indefinite periods, when such drugs, ultimately . . . will impair health, and when, by lulling patients into euphoria, they will destroy ambition and industry.”120