The scope of nature photography is very broad, and almost every piece of photographic equipment ever made could be useful at some time when photographing the natural world. The aim of this chapter is to highlight the most useful equipment.

I also explain why I personally find the equipment useful. Although images shot on film have been used for some of the examples in this book because they best suited a particular situation, film is for all practical purposes dead, so all the equipment advice is based on digital cameras.

CAMERAS

It is possible to take landscape pictures using digital compact cameras, but these are not practical for wildlife photography due to their fixed lenses of limited focal length. Most compacts only produce images in the jpeg format, which severely limits the post-capture control you have over your images. There are some compacts that can produce RAW files, and I use one of these myself – the Canon G9. The great advantage of using a compact is that you never have a problem with dust. This is because the lens is fixed to the camera body, so the dust just cannot get inside it. On the negative side, because these cameras have very small sensors they tend to suffer considerably with sensor noise. I found that the pictures from my G9 were unusable above 80 ISO.

At the other end of the scale are digital mediumformat cameras. However, these are incredibly expensive at the moment, and with digital technology evolving so rapidly I do not feel they are a good investment. They are also bulky, and although great for landscapes are not very practical for a wide range of wildlife photography.

The best overall cameras for nature photography are the 35mm-equivalent digital SLRs (Single Lens Reflex) cameras with interchangeable lenses. The two big players are Canon and Nikon, who tend to lead the way in the constant improvements that are being made as digital technology continues to evolve. I have been a Canon user for many years, and great rivalry seems to exist between users of Canon and Nikon. In reality both systems are excellent, and the choice of lenses and other accessories for them far exceeds that of any other manufacturer. There are other systems, of course, but if you are just starting out I suggest you choose one of the two leading brands.

There are a number of factors to consider when choosing a digital camera body. I have attempted to avoid the technical detail as much as possible and to keep the advice very practical.

Sensor Size | In the days of film, every camera produced the same-size image on 35mm film, which was 36 x 24mm. When it comes to digital cameras, the image size is determined by the size of the sensor that records the picture. When this approximates the size of a single 35mm film image, it is known as ‘full frame’. Nikon and Canon produce 35mm-like digital cameras with smaller sensors that effectively crop the centre out of the full-frame image, giving the impression that the subject has been magnified.

Cameras with full-frame sensors are generally relatively expensive, but they are the most useful for landscape photography because they do not crop images and therefore retain the full effect of wide-angle lenses.

Cameras with smaller sensors are useful for wildlife photography, because they effectively magnify the subject as they crop the full-frame image. Problems can occur with small sensors when manufacturers try to squeeze too many megapixels on them, resulting in excessive noise that can seriously degrade the image at even moderate ISO settings (see under Megapixels, below).

Burst Rate | This is the number of frames that can be taken continuously before the buffer fills up and the camera can no longer take pictures, until the buffer clears itself by transferring the image data to the flashcard. This is rarely an issue with relatively static subjects, but can be restrictive when photographing wildlife in action. My full-frame Canon 1Ds Mark II has a burst rate of 10 frames, while the Canon 1D Mark II has a burst rate of 22 frames, making the 1D Mark II my camera of choice when photographing (for example) birds in flight.

Frame Rate | This relates to the number of frames per second that can be taken by the camera body. Like the burst rate, it is not relevant to static subjects, but being able to shoot at eight frames a second or more is very useful for photographing wildlife in action.

Megapixels | In simple terms, this is the number of pixels used to create a picture, and it directly relates to the size of the final digital image. Many people take the view that the more megapixels the camera produces, the better the quality of the image, but this is not necessarily the case. The camera sensor is actually an array of millions of tiny sensors, and when too many are crammed into a small space the resulting image can suffer from noise. This has a very similar effect to the grain found in film, and increases with ISO speed. In the relatively short time since digital cameras became widespread, the control of noise has improved enormously. Future developments are bound to produce further advances.

In summary, I would recommend a body with a full-frame sensor for landscape photography, and a body with a smaller sensor for wildlife photography.

TYPES OF LENS

Zoom Versus Fixed Lenses | Zoom lenses have improved so much in quality that I now use them for much of my nature photography. Individual zoom lenses are usually heavier that their fixed-length counterparts, but they combine a wide range of focal lengths in one lens. This enables you to carry far less equipment than you would need if you had a range of fixed-length optics. Zoom lenses also have the advantage of enabling you to use focal lengths that are just not possible with fixed lenses (whoever heard of a 33mm lens?). In addition, they permit you to make adjustments to your composition without having to move backwards and forwards. On the negative side, zoom lenses have smaller apertures for their weight and size than lenses with fixed focal lengths. For many subjects this is not a concern, and with ever-higher ISOs available on digital cameras it is even less of an issue.

Despite the improvements in zoom lens technology, I would recommend buying the best zoom lens that you can afford. I use Canon professional ‘L’ lenses whenever I can because I know they are of the highest quality. A cheap zoom lens is not going to be a good investment, although there are a number of independent lens manufacturers who do produce good-quality optics. If you are on a budget, these can be an option worth considering.

Super telephoto lenses nearly always have a fixed focal length, because the prime requirement of these large and heavy lenses is to have as large a maximum aperture as possible, which is best achieved using a fixed lens. Other specialist lenses, such as macro and tilt and shift lenses, are also only available with a fixed focal length.

Image-stabilized Lenses | Many lenses now have Image Stabilization technology, known as IS on Canon cameras and VR (Vibration Reduction) on Nikons. As their names suggest, these lenses reduce the effect of camera shake when taking photographs. The technology comes into play particularly well when hand-holding lenses of all sizes, and I often take advantage of it when using a tripod is unsuitable or inconvenient. IS can get confused when a camera is used on a tripod, so because it is not required in this situation I turn it off.

USED ON A FULL-FRAME CAMERA, A STANDARD ZOOM LENS IS VERY VERSATILE, AND PERFECT FOR LANDSCAPE PHOTOGRAPHY. IT CAN EASILY BE HAND-HELD, AS IT WAS FOR THIS PICTURE OF SNOW-COVERED MOUNTAINS AND SEA ICE TAKEN FROM A MOVING SHIP.

Canon EOS 1Ds Mark II, 24-105mm lens, 1/500th sec @ f9, digital ISO 400

Svalbard, Norway

THE THREE BASIC LENSES

From the technical details with the pictures in this book, you will note that I have used a wide range of lenses over the years. However, if you are just starting out you can easily get by with just three key lenses to cover the majority of situations in nature photography. These are the standard zoom, telephoto zoom and super telephoto.

Standard Zooms | The range of focal lengths that the so-called standard zooms can cover seems to be increasing all the time. My standard lens at the moment is the Canon 24-105mm f4L IS, which at the 24mm end provides me with a very wide angle, and at the other end a short telephoto. I use this primarily for landscape and plant photography, and never go anywhere without it.

Telephoto Zooms | These cover longer focal lengths and are useful for all types of nature photography. My favourite in this category is the Canon 100-400mm f4.5- 5.6L IS. It has an awful push/pull zoom mechanism instead of the normal rotating zoom found in most lenses, but I love the flexibility of use the range of focal lengths provides. It is handy for landscapes, particularly when working in forests, and ideal for places like Antarctica, where you often have to shoot landscapes from far away on a ship. It is also the lens I use more than any other for photographing wildlife in the Antarctic, where the animals are approachable and a big telephoto is unnecessary. Being so much lighter than a super telephoto lens, it gives me the freedom to wander around looking for pictures.

There have been reports from some quarters that this lens is ‘not sharp’, but I have taken many thousands of pictures with it and the results have never been less than superb. It also has the advantage of having a 77mm filter thread, so it will take a standard-sized polariser filter, which comes into play when photographing landscapes. Although it will physically accept a teleconverter, I would advise against using one because in my experience doing so results in a significant degradation of image quality. Nikon produce an excellent 200-400mm zoom lens, but although the f4 aperture is useful, it is well over twice the weight of the Canon optic, so far less convenient to carry around, especially if you also regularly use a super telephoto.

An alternative telephoto zoom is a 70-200mm lens, several versions of which are made by both Canon and Nikon. It does not have the reach of the 100-400mm lens, but works well with a teleconverter, which provides that extra reach. I have the f2.8 version of this lens, which is very fast and still gives you f5.6 if used with the 2x converter. This works well with this lens, although I still prefer the flexibility of the 100-400mm for general work.

Super Telephoto Lenses | A big telephoto lens is pretty much essential for wildlife photography, and the 500mm f4L IS has now become the main workhorse in this field. The Canon lens weighs 4kg, and I nearly always use it on a tripod with a Wimberley head. The maximum aperture of f4 enables fast focusing, even when a 1.4x converter is used, since the effective aperture is then f5.6. Below f5.6, autofocus slows down considerably, and in some lower end cameras will no longer function at all. The IS feature is useful when working at slower shutter speeds on these long lenses, especially when using teleconverters, because the long focal length magnifies not only the subject, but also any camera movement or vibration, and IS helps to combat this.

A TELEPHOTO ZOOM IS VERY USEFUL FOR PICKING OUT DETAILS IN A LANDSCAPE, AS IN THIS COMBINATION OF BIRCH AND MAPLE TREES IN AUTUMN.

Canon EOS 1Ds Mark II, 100-400mm zoom lens @ 275mm, 0.5 sec @ f22, digital ISO 100

Michigan, USA

THE LONG REACH OF A SUPER TELEPHOTO LENS IS OFTEN ESSENTIAL WHEN PHOTOGRAPHING SMALL BIRDS SUCH AS THIS HAWFINCH (COCCOTHRAUSTES COCCOTHRAUSTES).

Canon EOS 1Ds Mark II, 500mm lens, 1/800th sec @ f4, digital ISO 400

Hungary

OTHER LENSES

Having covered the main three lenses that no nature photographer should be without, here are descriptions of several other more specialized lenses.

Macro Lenses | These are specialist lenses that enable much closer focusing than is possible with normal lenses. True macro lenses enable 1:1 or actual life-size images to be produced on a full-frame camera, and are perfect for photographing small insects and plants. Two focal lengths are most suited to nature photography, 100mm and 180mm (Nikon have 105mm and 200mm). For relatively static subjects, such as moths at rest and flowers, the 100mm lens is sufficient. The extra reach of the 180mm (or 200mm Nikon) is of great benefit for photographing more nervous subjects that are difficult to approach, such as dragonflies and butterflies, although these larger lenses are considerably more expensive.

For macro work, a camera with a small sensor, such as the Canon EOS 50D, is useful. With this, your 100mm macro becomes an effective 160mm macro at no extra cost.

Mid-range Super Telephoto | I would define this as either a 300mm f2.8 or a 400mm f4. Both these lenses come within the range of the 100-400mm zoom lens, and if you also have a 500mm f4 lens, why would you want one of these as well? The answer is: because of their combination of weight and brightness. For many years I owned a 300mm f2.8, but I sold this and bought the Canon f4 IS DO. The DO stands for Diffractive Optical, the use of which enables the lens to be smaller and lighter than a normal lens. This superb-quality lens weighs in at just under 2 kilograms, which is half the weight of the 500mm f4. When used with a 1.3x body and a 1.4x converter, it gives me the equivalent of a 728mm lens, which I can easily hand-hold. This makes it a perfect lens for photographing birds in flight, especially when you are attempting to capture small and fast-flying species. In such cases, hand-holding gives you the freedom of movement and ability to react quickly and track the often erratic bird flight. I have also used this lens when photographing from moving boats, situations where a tripod would be impossible to use. In addition, its relatively light weight makes it valuable in locations where you are wandering around a lot, but need a longer focal length than your long zoom can provide. It allows you to work without a tripod – and in this case the IS facility is very useful.

Ultra Wide-angle Lens | I would define ultra wide angle as any focal length smaller that 24mm, and lenses of this length are of value mainly in landscape photography. The difference of a few millimetres in focal length is very significant when working with wide-angle lenses. I use the Canon 17-40mm f4L, which overlaps quite a lot with my 24-105mm, but the difference between 17mm and 24mm is astonishing, with the angle of view increasing from around 73 degrees at 24mm to about 92 degrees at 17 mm. That is around 26 per cent more coverage for just a 7mm decrease in focal length. There are wider lenses than 17mm, but they have a limited use for nature photography and are costly.

A VERY WIDE-ANGLE LENS WAS REQUIRED TO INCLUDE THE FOREGROUND ROCKS AND DISTANT MOUNTAIN IN THIS IMAGE OF KICKING HORSE RIVER, YOHO NATIONAL PARK, DISAPPEARING THROUGH A NATURAL BRIDGE LIKE A GIANT WHIRLPOOL.

Canon EOS 1Ds Mark II, 17-40mm zoom lens @ 17mm, HDR image of several exposures

British Columbia, Canada

MY CANON 400MM F4 DO LENS AND 1.4X CONVERTER, WHEN COMBINED WITH MY 8 FRAMES PER SECOND EOS 1D BODY THAT HAS A BURST RATE OF 22, IS IDEAL FOR HAND-HELD IMAGES OF SMALL BIRDS IN FLIGHT, LIKE THIS SWALLOW (HIRUNDO RUSTICA).

Canon EOS 1D Mark II, 400mm lens + 1.4x converter, 1/2,000th sec @ f6.3,digital ISO 400

Suffolk, UK

Tilt and Shift Lens | Although these are specialist items, they can be of value to nature photographers in certain circumstances. Without going into great technical detail, the tilt control allows you to ‘tilt’ the angle of focus from the normal vertical to place it more horizontally. This is useful when photographing large and flat subjects such as fields of flowers. With a normal lens it can be difficult – and sometimes impossible – to achieve a sufficient depth of field to get both the foreground and background in focus, especially if you are using a telephoto lens and have the foreground flowers very close. This is because the plane of focus is vertical and the subject is horizontal.

To obtain the biggest possible depth of field, the subject needs to be parallel to the camera sensor. If you wanted to photograph a field of flowers, you would have to hover above the field and point your camera straight down to achieve this – a nice trick if you can do it. Using the tilt mechanism on the tilt and shift lens, you can tilt the plane of focus towards the horizontal and capture the scene in sharp focus, while keeping your feet firmly on the ground.

Even if you manage to get everything in focus by using a very small aperture on a normal lens, you will need to use a very slow shutter speed to obtain the correct exposure. If there is the slightest wind, the flowers will move around and will not come out sharp. With the tilt mechanism, you can use a much wider aperture and faster shutter speed. Although there are a number of focal lengths available with tilt and shift mechanisms, depth of field is much less of a problem with wide-angle lenses, so I find the Canon 90mm T/S lens the most useful.

The shift mechanism can be used to correct the tendency of a vertical lens to converge towards the centre when you point it upwards, which is especially the case with a wide-angle lens. It is often used for photographing buildings, but I have not found much of a use for it in nature photography, and much the same effect can now be achieved using software such as Photoshop.

Teleconverters | These are extremely useful, small, lightweight lenses. They fit between the main lens and camera body, and increase the effective focal length of the lens. They come in two sizes, 1.4x and 2x. The numbers refer to how much the focal length is increased when they are used. Thus a 500mm lens becomes a 700mm lens when used with a 1.4x converter, and a 1,000mm lens when used with a 2x converter. You do not, however, get something for nothing, and the downside is a reduction in quality and a loss of light. When using the 1.4x converter you loose one stop of light (so the 500mm f4 becomes a 700mm f5.6); with the 2x the loss is two stops (the 500mm becomes a 1,000mm f8). I only ever use Canon converters (if you are a Nikon user use only Nikon converters). There are less costly independent converters available, but these are unlikely to match the quality of the two prime brands.

In my experience, it is difficult to detect any loss in quality when using the 1.4x converter with most lenses (although as mentioned previously I would not use it with the Canon 100-400mm zoom). I use the 2x less frequently – although the image is good, the slight loss of quality is detectable. The quality of the image edge suffers more than that of the centre. Cameras with smaller sensors can thus give better results with the 2x converter than full-frame cameras, since in the case of the former the edges are cropped out when the picture is taken.

EXTENSION TUBES

These are hollow rings that fit between the camera body and lens, and reduce the minimum focusing distance of the lens. They can be of value when used with shorter lenses as an alternative to a macro lens, and if you only do macro work occasionally they are good for making large images of small subjects such as insects. Extension tubes are also useful when photographing small creatures such as hummingbirds with a long telephoto lens – on their own, most of these lenses will not focus close enough to enable you to produce a good-sized image of your subject.

FILTERS

The only filter I use is a polarising filter, which I find beneficial for several reasons. Its best-known effect is produced on a sunny day, when it darkens the blue sky and can bring out the detail in any white clouds present. I also use it when photographing forests whatever the weather, because it reduces the reflections from the leaves, in doing so making the colour far more intense.

The filter can be used for reducing the shutter speed when making long exposures of subjects such as waterfalls, because it results in the loss of around two stops of light. You could, of course, use a neutral-density filter to reduce the light reaching the sensor, which is what it is designed for, but I prefer the convenience of a polarising filter because it is usually on the lens anyway.

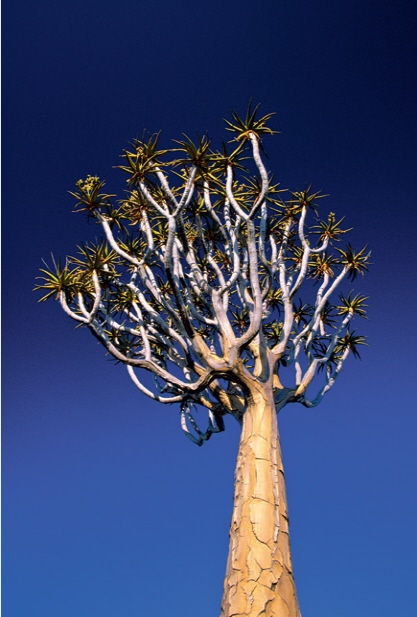

A POLARISING FILTER DARKENS A BLUE SKY AND PRODUCES A RATHER DRAMATIC IMAGE, AS IN THIS SHOT OF A QUIVER TREE (ALOE DICHOTOMA).

Canon EOS 1n, 24-85m lens, polarising filter, exposure unrecorded, Fuji Velvia film, ISO 50

Namibia

TRIPODS

Although I enjoy the freedom of hand-holding my camera, particularly when photographing wildlife, I still consider a tripod to be an essential piece of equipment and would not leave home without one. I have used a Manfrotto 055 tripod for many years. It is very sturdy, yet of a reasonably light weight, and has quick-release legs, something I would not be without. I cannot get on with tripods that have twist-lock legs and avoid them, and do not use carbon-fibre tripods. In my view the high cost of these tripods cannot be justified for the small weight savings to be gained. Of course, many people are happy with twist-lock legs and carbon-fibre tripods, so it comes down to personal taste and how deep your pockets are.

TO PRODUCE THIS RATHER ETHEREAL EFFECT WHEN PHOTOGRAPHING WATERFALLS, A VERY SLOW SHUTTER SPEED IS NEEDED, SO A TRIPOD IS ABSOLUTELY ESSENTIAL.

Canon EOS 1Ds Mark II, 24-105mm zoom lens @ 45mm, 5 sec @ f16, digital ISO 50

Michigan,USA

Why is a tripod essential for nature photography? There are perhaps more reasons for using a tripod than you might think.

Preventing Camera Shake | The most obvious reason for using a tripod is to prevent camera shake during the exposure. This facility is clearly most useful when making long exposures due to either low light conditions or using small apertures to increase the depth of field.

Long Waits | Nature seldom does what you want it to do, and when taking photographs of nature you will frequently spend a great deal of time hanging around waiting for something to happen. You may have to wait for the sun to appear from behind the clouds for a landscape, for a bird to return to its nest, or for a mammal to appear and carry out a specific action. Even if you are using a normal lens, it is far easier to have your camera set up on a tripod ready to use, than to hold it for a long time.

Taking the Weight | Unless you are built like Arnold Schwarzenegger, some of the super telephoto lenses are just too heavy to hand-hold and really do need a tripod just to support them. The Canon 500mm f4 weighs about 4 kilograms, and I very rarely use it without a tripod.

Remote Control | There may be occasions when you want to operate your camera remotely, and in such cases a tripod is usually required to support the camera close to your subject.

Aligning Images | If you want to produce HDR images (discussed in later chapters), you will need to take several different exposures of exactly the same scene. A tripod is essential to ensure that the camera remains in the same place for each exposure, so that each image in the sequence is precisely aligned.

Composition | A powerful creative reason for using a tripod relates to composition. Once you have your camera set up on the tripod and in position, you can take your time and carefully consider the shot, making small adjustments by moving the camera around or by zooming in and out. Obviously, the luxury of having the time to do this only really applies to rather static subjects, and is particularly relevant when photographing landscapes.

TRIPOD HEADS

There is a vast array of tripod heads to choose from. I have tried a few over the years, but have now settled for two. When employing long and heavy telephoto lenses for wildlife photography, I use a Wimberley head. This is a very specialized gimbal-type head, which rotates the lens around its centre of gravity, instead of the whole thing being balanced on top, as is the case with other types of head. The lens is attached using its tripod collar via an Arca Swiss-type mount. This can be adjusted backwards and forwards until the lens and camera combination you are using is perfectly balanced. Once this has been accomplished (which only takes a minute or so), the entire weight is taken by the tripod and the camera simply hangs in place ready to be moved around with ease. If you have a large telephoto lens such as a 500mm or 600mm f4, you really must get a Wimberley head.

For all other tripod work I use a small and lightweight ball-and-socket head made by a US-based company called Really Right Stuff. This also comes with an Arca Swiss-type clamp, and the same company additionally supplies specially designed plates for a wide range of camera bodies that fit into the clamp. The plates are well worth buying, because they are designed to prevent the camera body from twisting once it is on the head – a problem with quite a few ‘one size fits all’ tripod-mount systems, many of which are more trouble than they are worth.

FLASHGUNS

I am not a great user of flash for much of my nature photography, although I do use it quite a lot for macro work, especially when photographing invertebrates. I often use fill flash when photographing static insects such as moths at rest. During the day many moths are inactive and can be found sleeping on a variety of surfaces, although they tend to always be in relatively cool shade because they dislike bright sunlight. Photographing them in these rather dull conditions does not bring out their subtle colours and textures, so I use a standard flashgun to provide additional light in the form of fill flash, setting the flash compensation at between -1 and -1.5 stops to prevent the flash from overpowering the ambient light.

This approach works well for static subjects that allow you time to set up the camera on a tripod, but I tend to use full flash when photographing more active insects, such as bees and hover-flies. The depth of field in macro photography is minimal, so a small aperture is required to increase this as much as possible. This in turn requires a slower shutter speed, so ambient light will not be strong enough to allow a fast enough shutter speed for a handheld shot. I find this technique particularly beneficial when using a ring flash, which fits around the end of the lens on the filter ring. Ring flash is of value when photographing small insects, because the flash is concentrated directly on the subject and gives a very even light with few shadows.

FILL FLASH IS USEFUL FOR BRINGING OUT THE INTRICATE DETAILS OF INSECTS LIKE THIS MARBLED CARPET MOTH (CHLOROCLYSTA TRUNCATE) AT REST DURING THE DAY.

Canon EOS 1Ds Mark II, 100mm macro lens, Canon 580Z flashgun, 1/3rd sec @ f22, flash compensation at -1 1/3rd stops, digital ISO 100.

Essex, UK

A RING FLASH IS IDEAL FOR PHOTOGRAPHING SMALL INSECTS LIKE THIS MARMALADE HOVER-FLY (EPISYRPHUS BALTEATUS) FEEDING ON A GAZANIA FLOWER IN MY GARDEN.

Canon EOS 50D, 100mm macro lens, ring flash, 1/250th sec @ f16, digital ISO 100

Essex, UK

USING A REMOTE RELEASE ENABLED ME TO GET UP CLOSE AND USE A WIDE-ANGLE LENS TO TAKE THIS PICTURE OF A WOODPIGEON (COLUMBA PALUMBUS) AT A GARDEN BIRD BATH.

Canon EOS 1Ds Mark II, 24-105mm zoom lens @ 38mm, 1/40th sec @ f14, digital ISO 400

Essex, UK

REMOTE RELEASE

A remote release enables you to fire the camera shutter from a distance, which can be useful when photographing wildlife. Clearly you need to predict exactly where your subject will appear, and I have used it to photograph birds visiting a bird bath in my own garden, as shown in the image of a Woodpigeon above.

It is easy enough to photograph birds from a distance with a long telephoto lens, but in this particular instance I wanted to get in close and use a wide-angle lens for a more intimate view that showed the garden as well. The camera needed to be less than a metre away from the subjects, so a hide would almost certainly have put them off. I therefore set up the camera on a tripod with a remote wireless trigger, and went indoors.

The birds ignored the camera and came down to the bird bath almost immediately, enabling me to use the remote to trigger the camera through the window and get some nice images of a familiar scene.