This chapter discusses photographing the freshwater marshes and rivers, and the wildlife that can be found in these habitats. Wetlands in particular are essential wintering grounds for millions of birds throughout the world.

Marshland is often regarded as ‘waste’ land by humans, and much of it has been drained for farming. Despite this, the small patches of marshland that are left still provide rich pickings for the nature photographer – they are certainly one of my favourite ecosystems for bird photography. Wildlife that you can encounter here includes countless birds such as waders, herons and ducks, and insects like dragonflies and butterflies.

THE OPEN LANDSCAPE

I find photographing the flat open landscape of wetlands difficult to execute well, and had to dig back as far as several years into my image library for the opening shot of the Biebrza Marshes in Poland. The trouble with this habitat is that there is very little in it, so producing an interesting image is challenging. The Biebrza Marshes are huge, covering around 1,000 square kilometres. I felt that the flowering plants covering the vast area of shallow water supplied sufficient interest to make a successful picture. In order to capture the scale of the place, I used a wide-angle lens. The blue sky was dotted with fluffy white clouds that added interest not only to the sky itself, but also to the water that reflected them.

In relatively featureless landscapes such as marshes, a way to create interest in a picture is to photograph at dawn, when the first rays of the sun give colour to the scene. The warmer the air is, the more moisture it can absorb, so as the temperature increases during the day more and more water from the marsh evaporates into the atmosphere. During the night, as the temperature falls, the moist air can no longer contain all the water, and in still conditions mist forms over the marsh. Shooting towards the sun at dawn on a still day, the back-lit mist adds drama to the scene, as can be seen in the picture above taken at Bosque del Apache National Wildlife Refuge in New Mexico. These conditions do not last long, so you have to be in position before sunrise and wait for the right moment. In this case the mist was rising some distance away and I had to use a long telephoto lens to make the most of it. The scene was impressive – the marsh appeared almost ablaze – but I needed a focal point to hold it together, and positioned a lone willow tree to the right of the frame to achieve this. As the sun rose further, the mist quickly burned off and the colour disappeared.

BIEBRZA MARSHES

BIEBRZA MARSHES

Canon EOS 1n, 24-85mm lens, exposure unrecorded, Kodachrome 64 ISO film

Poland

MIST AT SUNRISE

MIST AT SUNRISE

Canon EOS 1n, 500mm lens, exposure unrecorded, Fuji Provia film, ISO 100

New Mexico, USA

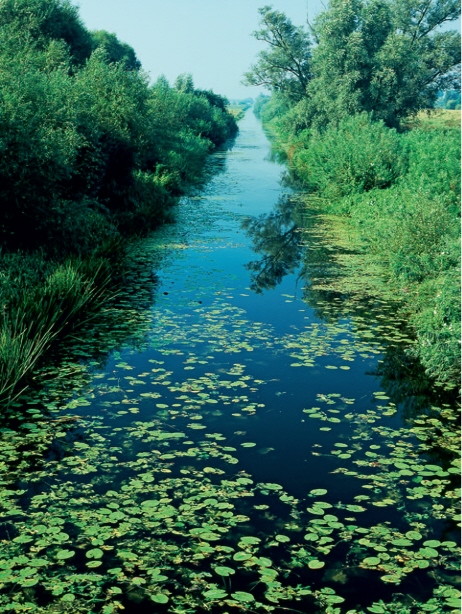

OLD BEDFORD RIVER

OLD BEDFORD RIVER

Bronica ETRs, 200mm lens, exposure unrecorded, Fuji Velvia film, ISO 50

Norfolk, UK

RIVERS

Ironically, the Old Bedford River in the picture is man-made, having been built to drain the fenlands of East Anglia in the early 1600s. With the creation of a deep straight channel from the Great Ouse River to the sea, the low-lying fens were starved of water and dried out. This act of ecological vandalism destroyed nearly all of the wild fenland that had existed here for many tens of thousands of years.

From a photographic point of view, it was the arrowstraight line of the river as it disappeared into the distance that attracted me. To make the most of the elongated shape I turned the camera on its side and shot in portrait mode, because this way as much of the river as possible could be included in the frame. A simple composition further emphasized the shape, and I placed the river slapbang in the middle of the frame. I used a polarising filter to reduce the reflection in the water and darken it, which made the floating vegetation stand out.

FLOWING WATER

Fast-flowing rivers can make very interesting subjects, because the movement of the water can be used to add interest to a scene.

Sol Duc Falls in Olympic National Park, Washington State, are reached by a well-marked trail, but the falls themselves are pretty unimpressive and not very photogenic. Even though it was late June when we arrived there, this far north the Aspen leaves were still a bright yellow-green, and their colours were reflected in the Sol Duc River, just above the falls. It was an overcast day and the light under the canopy was very poor, but the colours made the river look like a flow of liquid metal and it was crying out to be photographed.

I set up the tripod on the riverbank and chose an interestingly shaped rock in the river as a focal point. The resulting two images, shown above, illustrate how selecting different shutter speeds affects a picture when photographing moving water. The longer the exposure, the more movement is recorded, and the more blurred the water becomes.

In the second pair of pictures, shown above right, you can see how this effect is exaggerated when the water is tumbling over a waterfall because it is moving much faster. Personally, I much prefer the ethereal effect of the water that can be obtained when you are using a slow shutter speed, even though the faster shutter-speed image does look more natural.

SOL DUC RIVER

SOL DUC RIVER

1A Canon 1Ds Mark II, 28-135mm zoom lens @ 70mm, 1/4th sec @ f8, digital ISO 200

1B Canon 1Ds Mark II, 28-135mm zoom lens @ 70mm, 8 sec @ f22, digital ISO 50

Washington State, USA

LOWER LEWIS FALLS

LOWER LEWIS FALLS

2A Canon 1Ds Mark II, 28-135mm zoom lens @ 135mm, 1/60th sec @ f5.6,digital ISO 200

2B Canon 1Ds Mark II, 28-135mm zoom lens @ 135mm, 1.5 sec @ f22, digital ISO 50

Washington State, USA

Overcast days are best for this type of photography, because it is often impossible to get a sufficiently slow shutter speed on bright sunny days. To help achieve the slowest speed possible I use a polarising filter, which effectively adds a couple of stops.

A big advantage of digital is that you can change the ISO rating for each shot, which means that you can use the slowest ISO available to obtain the longest exposure possible, then up the ISO for the next shot when you want a fast shutter speed. On most digital cameras the minimum ISO is 50.

I used a small waterfall as the foreground in the next picture, which at first glance looks as though it was taken on the coast. It was quite a windy day and the waves were breaking along the shoreline, but this ‘coastal’ scene is in fact the southern shore of Lake Superior, the largest freshwater lake in the world.

The waterfall was not an impressive sight because it only dropped half a metre or so, but photographed up close with a relatively wide-angle lens it made an impressive foreground. I worked the scene using various focal lengths, although I could not go too wide because the position of the sun was such that I had to avoid obstructing the image with my shadow – it is just out of shot near the bottom of the frame.

The white clouds in the blue sky pick up the white surf in the waves, and this theme is continued in the white hue of the waterfall itself. All the elements are in place in this landscape shot, which is certainly my favourite waterfall image.

WATERFALL AND LAKE SUPERIOR

WATERFALL AND LAKE SUPERIOR

Canon 1Ds Mark II, 24-105mm zoom lens @ 40mm, 1/10th sec @ f16, digital ISO 50

Michigan, USA

AMERICAN WATER-LILY (Nymphaea odorata)

AMERICAN WATER-LILY (Nymphaea odorata)

Canon EOS 1n, 300mm lens, exposure unrecorded, Fuji Provia film, ISO 100

North Carolina, USA

PLANTS

A number of plant species thrive in damp boggy conditions in marshy areas or at the sides of rivers, but some, like water-lilies, grow in permanent shallow water and can be considered true aquatic plants. They are commonly grown in garden ponds, but in the wild can completely cover large areas of water. They do not like fast-moving water, so the still water in a cypress swamp in North Carolina is the perfect environment for the white-flowered American Water-lily featured in the above picture.

Unfortunately, when I came across the plants they were some distance away across open water with a few cypress trees dotted about. I wanted to fill the frame with water-lilies, but needed to use a telephoto lens to do this. I could not use a tripod because the only clear shot through the trees was too high, so I leaned against a tree trunk and took the shot hand-held. Due to the shallow depth of field of the telephoto lens, it was impossible to get the whole frame in sharp focus, so I concentrated on the foreground and let the background go, which was the best compromise. What I really needed was a 300mm tilt and shift lens to control the plane of focus, but such an optic does not exist.

The Marsh Orchid in the next picture prefers damp marshy conditions, and in appropriate habitats can be quite common. When I saw this particular flower on the Shetland Isles it was surrounded by rough grass, so it was difficult to get a clear shot of it. Rather than start ‘gardening’ the area around the flower, I decided to try and use the surrounding vegetation in the picture. I lay down on the rather wet ground in order to shoot at the same level as the orchid. This meant shooting through some of the grass. I did not want this to detract from the flower itself, so used a relatively wide aperture of f8 to restrict the depth of field. An even wider aperture could have been used, but I wanted to keep as much of the main subject in focus as possible. Working close-up, depth of field is minimal, so f8 was a good compromise. I liked the ‘V’ shape made by the grass in front of the orchid, which was mirrored by a similar ‘V’ in the grass behind and to the left of the flower. There were some daisies in bloom in the background. I kept them in the frame because their soft, out-of-focus shapes provided background interest.

MARSH ORCHID (Dactylorhiza majalis)

MARSH ORCHID (Dactylorhiza majalis)

Canon 1Ds Mark II, 100mm macro lens, 1/320th sec @ f8, digital ISO 400

Shetland Isles, UK

The final picture here, shown right, is of lichen – something I had not set out to photograph when visiting the Corkscrew Swamp Sanctuary in Florida, but could not resist when I came across it. The whole sanctuary is so wet underfoot that access is via an extensive wooden boardwalk that takes visitors into the heart of an otherwise inaccessible habitat. Much of the area is rather overgrown cypress swamp, so wildlife viewing is difficult and photography even more so. Some of the trees had large pink-coloured lichens on them, but these were difficult to photograph well because they were some way off the boardwalk. I noticed that some of the older parts of the boardwalk itself had colonies of the same lichen, which I later found out was called Baton Rouge. The smooth flat wood of the boardwalk was perfect for photography, so I set about searching for potential compositions.

I did not have a macro lens with me, but the 90mm tilt and shift I had put in the gadget bag focuses very close, and this was a good substitute for a true macro lens. Due to the dull light a slow exposure was required, which was not a problem because I was using a tripod. The biggest obstacle to getting a sharp image was other visitors – anyone walking along the raised boardwalk would cause it to move and the vibrations would spoil the shot. Eventually, though, we found a big enough break in the traffic to get some pin-sharp pictures.

BATON ROUGE LICHEN (Cryptothecia rubrocincta)

BATON ROUGE LICHEN (Cryptothecia rubrocincta)

Canon 1Ds Mark II, 90mm tilt and shift lens, 1/4th sec @ f16, digital ISO 100

Florida, USA

BIRDS

Rivers have birds that breed in this specialized habitat, but marshes are one of the best ecosystems in the world for birds and bird photography. Many species breed in marshland, and during the winter thousands of birds gather together in these often remote places that are vital to their continued existence. The Ouse Washes are one such wintering area. They are an artificially created habitat used to contain the floodwaters of the River Ouse, preventing the surrounding farmland from returning to the natural fenland that it replaced. In the winter they are an important wintering ground for several species of wildfowl. I chose a picture of a Mute Swan from this location as my first wetland bird image.

I had noticed the clear channel running through the reeds from the foreground, and thought it would make a nice picture of the washes themselves. As I set up to take the shot, I noticed the swan swimming around beyond the first bank of reeds, and thought it would vastly improve the picture if only it would pose in the right place. I watched it for some time as it meandered around, first swimming one way, then another. Eventually it started to swim across the gap in the reeds and I got the shot I was after.

To frame the shot as I wanted it, I had to use a focal length of 145mm, but because both the foreground reeds and the mid-distance swan had to be in sharp focus I had to stop down, and ended up taking the shot at f20. It was a bright day and I shot at ISO 400, so was still able to use a reasonably sharp shutter speed to freeze the slow-moving swan.

MUTE SWAN (Cygnus olor)

MUTE SWAN (Cygnus olor)

Canon 1Ds Mark II, 70-200mm zoom lens @ 145mm, 1/250th sec @ f20, digital ISO 400

Norfolk, UK

Ducks are, of course, a group of birds that you would associate with wetlands. The picture of a drake Pochard flying low over the water was also taken on the Ouse Washes during the winter months. The Pochard winters in large numbers in this habitat, and nearly all the birds encountered are males. Surprisingly, the males and females winter separately, with the females gathering in the much warmer climate of Spain during the winter months. The colourful males are far more photogenic than the rather drab females, so this is really good news for UKbased photographers.

The Pochards can easily be viewed from the hides at the Welney Wildfowl and Wetlands Trust Reserve. Food is put out each day, mainly for the wintering swans, but the Pochards have got used to the free handouts and hang around for most of the day. It can get quite crowded at feeding times, so picking out individuals as they fly around in front of the hides can be tricky. A long lens is necessary, and taking into consideration the 1.3x multiplication factor of the camera body, I photographed this individual with the 35mm equivalent of a 910mm lens.

POCHARD (Aythya ferina)

POCHARD (Aythya ferina)

Canon 1D Mark II, 500mm + 1.4x converter, 1/1,000th sec @ f5.6,digital ISO 200

Norfolk, UK

The extensive wetlands at Bharatpur in India also attract vast numbers of birds, some breeding and many others wintering there. One common species is the Grey-headed Swamp-hen, a wetland specialist that spends much of its time feeding on aquatic vegetation.

Before taking the above shot, I found a spot where 20 or so of these birds regularly foraged during the morning. When I first arrived and set up my equipment at the edge of the marsh they moved away, but after ten minutes or so they ignored me and went about their business as usual. They fed almost constantly, and I took a few pictures of this behaviour and a few portraits, but nothing special. Suddenly, the entire group of birds panicked and ran for cover. This was completely unexpected, so I did not get any pictures and wondered what had happened.

GREY-HEADED SWAMP-HEN (Porphyrio poliocephalus)

GREY-HEADED SWAMP-HEN (Porphyrio poliocephalus)

Canon 1D Mark II, 500mm, 1/1,250th sec @ f4, digital ISO 400

Bharatpur, India

As I looked up a large bird of prey passed overhead. Clearly the swamp-hens had seen the raptor long before I had, and feeling rather vulnerable out on the open marshland had headed for the cover of the trees and bushes that grew around the margins.

It was only a few minutes before the swamp-hens returned to their feeding grounds. There are a large number of wintering raptors at Bharatpur, so I thought it quite likely that another one would appear and cause another panic. This time, however, I would be ready, and was determined to photograph the swamp-hens as they ran for cover. These heavy birds do not fly very much, but as they run they hold their wings high in the air. This was the shot I wanted. It took three mornings and several eagle fly-bys until the shot was in the bag, but I felt the effort was well worth it.

I could not write about wetland birds without including a couple of pictures from my favourite bird-photography location, which is Bosque Del Apache National Wildlife Refuge in New Mexico. Tens of thousands of Snow Geese spend the winter here, roosting in the wetter areas of the reserve, where they are relatively safe from land-based predators such as Coyotes. As the sky starts to brighten in the pre-dawn light, the geese start to get restless, suddenly taking flight and leaving the roost to head off to the surrounding fields to feed. To see this spectacle you have to be on site very early, and in winter the temperature is likely to be below zero. The biggest challenge to the photographer is the light, or rather lack of it, because sometimes the geese take off very early indeed. Do not let ridiculously slow shutter speeds put you off, though, because they can produce interesting results.

When there are clouds in the sky they are sometimes lit up by the rising sun, making the sky reasonably bright. However, on this particular morning the sky was pretty clear, and 1/6th second was the fastest shutter speed available to me at ISO 400. It goes without saying that at these speeds the camera has to be on a tripod. This prevents camera shake, but cannot possibly freeze the movement of the flying geese as they cross the sky. The result is a sharp background, but the geese are recorded as ethereal streaks across the pink-tinged dawn.

The following Bosque picture shows the other main winter visitor to the reserve, the Sandhill Crane. Unlike the Snow Geese, the cranes leave their roost sites in small groups rather than in one great flock, and do so over a much longer period of time. By the time this group left the sun was well up, although it was still around 7 a.m. There was no wind, so the small roost lake had a perfect reflection of the surrounding rather stark countryside. As I watched previous groups fly off, I noticed that although most of them would fly too high, sometimes they would be low enough to enable the lake and reflection to be included in the picture. Finally a group of four birds arrived at just the right height and I pressed the shutter.

The final image of birds is one of a Dipper, a species that has made rivers its home. The Dipper prefers fast-flowing streams, so hilly areas tend to be the best places to see it. I photographed this one in the Peak District in northern England during early spring. In this particular location the river is surrounded by trees, so it is best to photograph the birds before the leaves break on the trees and create too much shade. The Dipper regularly perches on its favourite rocks along the river. Once you have identified these, the best strategy is to sit quietly on the riverbank nearby and wait for the bird to appear. Dippers feed primarily on river invertebrates, wading into very fast water to catch their food. In this case the bird has caught a caddis fly larva, one of the Dipper’s favourite snacks.

SNOW GEESE (Anser caerulescens)

SNOW GEESE (Anser caerulescens)

Canon 1Ds Mark II, 24-105mm zoom lens @ 32mm, 1/6th sec @ f4, digital ISO 400

New Mexico, USA

SANDHILL CRANES (Grus canadensis)

SANDHILL CRANES (Grus canadensis)

Canon 1Ds Mark II, 24-105mm zoom lens @ 50mm, 1/2,000th sec @ f8, digital ISO 400

New Mexico, USA

DIPPER (Cinclus cinclus)

DIPPER (Cinclus cinclus)

Canon 1Ds Mark II, 500mm lens + 1.4x converter, 1/200th sec @ f5.6,digital ISO 400

Peak District, UK

MAMMALS

The vast wetlands of the Orinoco Delta in Venezuela are known as the Llanos. They support huge populations of Capybara, also known as the Orinoco Hog. These animals can grow to up to a metre long and are the world’s largest rodent. They are very much adapted to life in swampy areas, and even have slightly webbed feet. They can occur in large herds. If danger threatens while they are grazing on land, they rush into the water and swim away from the bank to where land-based predators cannot reach them.

I photographed the group shown below from a small boat after a horse rider had just galloped along the bank where the Capybara were resting. They dived into the water and swam towards us. As they got closer I wanted to capture the whole scene, so fitted a short lens to the camera. Although they did not panic when they noticed us, they turned slightly to avoid us, heading up a channel clear of vegetation. As the last animal came into shot I took the picture. The line of Capybara heading into the frame with the vast empty wetland behind it provides an attractive composition.

CAPYBARA (Hydrochoerus hydrochaeris)

CAPYBARA (Hydrochoerus hydrochaeris)

Canon T90, 50m lens, exposure unrecorded, Kodachrome 64 film

Venezuela

Some mammals, such as Racoons, occur in a wide variety of habitats, including towns, and when I saw a pair of youngsters sifting through the mud at the edge of a shallow wetland in Florida, I could not resist photographing them. We were sitting in the car eating lunch, when a Racoon mother and her two young appeared. The young were about half the size of the adult, and she seemed happy to leave them to their own devices as she wandered around searching for food. Because this was Florida, I reckoned that Racoons were probably as used to people as birds, so I fitted a telephoto zoom lens to my camera and quietly got out of the car. Being lightweight, the zoom lens gave me a great deal of freedom to follow the Racoons around, and I could easily hand-hold it, so did not need the cumbersome tripod.

The Racoons mostly wandered around the side of the dirt road, possibly looking for discarded bits of food, so there was not much of a background for photography. Then they both moved into the shallows and started turning over rocks with their front paws.

I crouched low to get a good angle and waited until the two animals drew side by side. This gave a good image, and with both of them in the same plane the depth of field was enough for the two of them.

RACCOONS (Procyon lotor)

RACCOONS (Procyon lotor)

Canon 1D Mark II, 100-400mm zoom lens @ 330mm, 1/320th sec @ f8, digital ISO 200

Florida, USA

SAMBAR (Cervus unicolor)

SAMBAR (Cervus unicolor)

Canon 1D Mark II, 500mm lens + 1.4x converter, 1/800th sec @ f5.6, digital ISO 400

Bharatpur, India

The final wetland mammal image shows a Sambar deer in early-morning mist. As previously mentioned, such mists are a feature of many wetlands. At the world-famous Bharatpur Reserve in India they occur almost every morning and sometimes last most of the day. This can make photography difficult, of course, but can also provide opportunities for producing atmospheric images. The distinctive shape of the male Sambar in the distance made a nice silhouette. The shrubby background that would normally have looked a bit of a mess was rendered much softer by the mist.

When photographing silhouettes you cannot make out much detail on your subject, so it is essential that its outline is clear and distinct. You must wait for the right moment or change your angle to achieve this, otherwise all you will end up with is an indistinct-looking blob. The other major consideration when photographing in mist is the exposure. Misty scenes tend to be at least one stop brighter than mid-tone, and if you rely solely on the camera exposure meter you will end up with an image that is underexposed. Working with digital it is easy to make a quick test exposure, then dial in compensation to make sure you get it spot on.

REPTILES AND AMPHIBIANS

There can be little doubt that the crocodile family is the most impressive group of wetland-loving reptiles. Being such large predators, crocodilians are feared by humans; this, combined with the use of their skins for the vain and superficial fashions of certain humans, has led to their downfall in many countries, although nowadays the destruction of their habitat is probably the biggest threat to their survival. Although alligators were hunted to the brink of extinction in the past, Florida now holds large numbers, which are easily seen in many of the state’s excellent reserves. One of the best places to see them is the Everglades National Park, where both of the pictures shown here were taken.

AMERICAN ALLIGATOR (Alligator mississippiensis)

AMERICAN ALLIGATOR (Alligator mississippiensis)

Canon 1D Mark II, 100-400mm zoom lens @400mm, 1/250th sec @ f5.6, digital ISO 400

Florida, USA

We were working the Anhinga Trail and came across a heron that had caught a large fish and was standing by the edge of the water with its prize. I was focused on it when it suddenly dropped the fish, called loudly and flew off. At first I was puzzled by this behaviour, but as a huge alligator emerged from the shallows next to where the heron had been standing, realized that the bird’s behaviour had been quite sensible. The prehistoric beast reached over towards the abandoned fish, took it in its impressive jaws and disappeared with it, back under the water. I am sure it would have been more than happy to have taken the bird with it too had it stayed around. The alligator was too close for me to use the big telephoto, but fortunately I had the 100-400mm zoom set up on another camera body and quickly switched to that. It was a windless day and the reptile’s head was reflected in a small section of water at the very edge of the bank. I stood as tall as possible to capture as much of this as I could, getting a couple of shots before the action was over.

The second alligator image was also taken on a leaden-sky day at the Anhinga Trail. To explore the area we used several boardwalks that crossed very muddy wetland, as well as areas of open water that were populated by some enormous alligators. Occasionally they would swim under the boardwalk, which was only a metre or so above the water. This provided a rare opportunity to photograph them from directly above. Most of the body of each alligator remained under the water, so I decided to frame the picture to show just the head of a reptile. The grey sky reflected in the water added to the final image, which would have had far less impact on a sunny blue-sky day.

With the increasing pressure on the remnants of wetlands, garden ponds have become more and more important as refuges for wetland wildlife, and my rather small pond is certainly a haven for frogs in the early spring. The surface is covered in frogspawn, and later in the year tiny froglets can be found hopping around everywhere. I have a water-lily in the pond, and the tiny frogs clamber over the lily pads and the flowers themselves. They look very photogenic in the large flowers, so I set up the shot with a macro lens and flashgun and ‘encouraged’ a couple of the little amphibians onto the nearest bloom to get the picture.

AMERICAN ALLIGATOR (Alligator mississippiensis)

AMERICAN ALLIGATOR (Alligator mississippiensis)

Canon 1D Mark II, 100-400mm zoom lens @160mm, 1/160th sec @ f5, digital ISO 400

Florida, USA

COMMON FROG (Rana temporaria)

COMMON FROG (Rana temporaria)

Canon EOS 1n, 100mm macro lens, autoflash, 1/200th second at f16, Fuji Velvia film, ISO 50

Essex, UK

INVERTEBRATES

Large numbers of invertebrates are completely dependent on rivers and wetlands for their existence. Many species of flying insect, for example, spend nearly all of their lives underwater during their larval stages, and only crawl out when the adults are ready to emerge. The dragonfly family is one such group, and being relatively large it is possible to photograph its members without specialist equipment. I have always loved the challenge of photographing birds in flight, so could not resist having a go at dragonflies as they flew around a local slow-flowing stream. The species in question was the Common Darter. With a body length of just over 40 millimetres this is not the largest of dragonflies, but there were a lot of them about and a target-rich environment is important when you are trying something with such a high degree of difficulty.

COMMON DARTER (Sympetrum striolatum)

COMMON DARTER (Sympetrum striolatum)

Canon 1D Mark II, 70-200mm zoom lens + 1.4x converter @ 280mm, 1/1,600th sec @ f4, digital ISO 400

Essex, UK

Dragonflies can change direction in a fraction of a second, so they are very tricky to follow with a camera. Being so small, photographing them is difficult, because the depth of field gets narrower the closer you are to your subject. They also move very quickly, so a fast shutter speed is essential – you cannot stop down to increase the depth of field available. My favourite lens for this type of work is the 70-200mm f2.8, which is very bright, will focus quite close and is also fast focusing. At its maximum of 200 millimetres you still have to get too close to your subject for a good-size image, so I add a 1.4x converter and use a camera with a 1.3x magnification. Putting all this together you end up with the equivalent of a closefocusing 364mm f4 lens, which allows a reasonable working distance from the subject.

The image shown above is of a pair of Common Darters flying over the stream looking for suitable places to lay their eggs. The male grips the female on her head and holds her up as she dips her abdomen into the water to lay her eggs. It is quite a remarkable piece of behaviour.

I was sitting in a public hide on the Ouse Washes in Norfolk photographing birds one mild winter’s afternoon, when I saw some dancing mayflies a distance away. They looked good in the soft sunlight, but I could not exactly get out of the hide to get closer because this would have frightened all the birds away. Determined to get a shot of some sort, I used my biggest lens, a 500mm telephoto, and fitted it with a two times converter, giving me the equivalent of a 1,000mm lens. The winter sun was not very bright and I used a 1/15th of a second shutter speed, ridiculously slow for such a large focal length. I steadied the lens on the Wimberley head, turned on the lens IS facility to combat camera shake and took a few shots. I have to say that this is the only time I have ever used a 1,000mm lens for photographing insects – you never know what lens might come in useful for a subject.

The result is an interesting image – although it does not seem to suffer from camera shake, the slow shutter speed was not, of course, sufficient to freeze the mayflies’ movements as they danced in a group. Interestingly, many of the mayflies were recorded as four separate images during the exposure, each one slightly higher in the picture than the last. This would indicate that to stay airborne they carry out a series of little mid-air ‘jumps’ at the rate of around 60 a second, another amazing piece of behaviour in the small-scale world of invertebrates.

MAYFLY (Ephemeroptera species)

MAYFLY (Ephemeroptera species)

Canon 1Ds Mark II, 500mm lens + 2x converter, 1/15th sec @ f11, digital ISO 400

Norfolk, UK