CHAPTER THE THIRD

PERTAINING TO THE UNWRAPPING OF A STINKY CHEESE

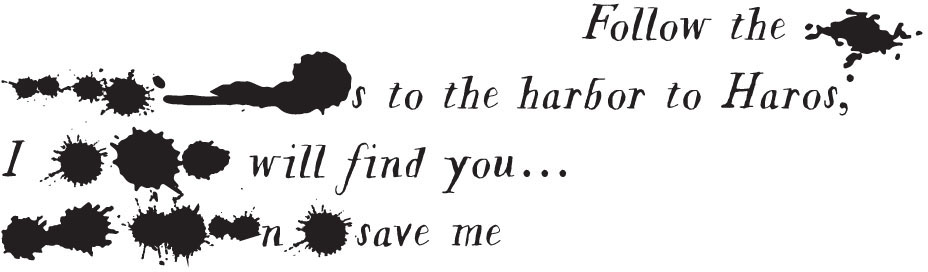

FOR A LITTLE WHILE, AFTER THE MUCK-COVERED SWINEHERD had disappeared, Clo continued to sit under the pine. She read and reread the ink-splattered letter and worked despairingly at the woolen knots on her father’s parcel while night thickened around her.

She turned the word sea over and over in her mouth.

She thought of returning to the town and finding her way to the barns and the swine among whom her father was said to have crouched, or of sleeping there, at the edge of the forest, and seeing what morning might bring. But the urgency of her father’s note—its hasty scrawl, its ink splatters—and the story of the cook, the worry that her father might have been recognized, compelled her to go.

A day’s walk through the woods. A night’s walk?

She would go to the harbor. The sea. If there was nothing there—no Haros, whatever that might be—if she could not find her father, she would return. It was a day.

She gathered her belongings and entered the dark of the woods.

Under a thick slice of moon, the forest was more gray than black—shades of darkness that suggested rather than defined forms. Clo followed the space in the darkness, the gray ruts of the wagon path, easily enough. The words of the swineherd, crouchin’ in th’ pens, hurried her along.

Another girl—wall-climber or no—or another boy—turnip-picker or no—really, most any inhabitant of the town might find the night of the forest too dark to enter. Too full of the shufflings of unseen creatures and windshook leaves. Too full of teeth and claws—of wolf, of bear, of bands of thieves. But Clo, wall-jumper, turnip-bearer, letter-reader, was not scared of the dark. Not truly. She had spent too many nights under the stars on her journeys with her father. The dry rustlings of the forest, even those of wolves and bears, had ceased to startle her long ago.

And the rustlings of thieves? Thieves with flashing teeth and flashing nails and flashing silver blades? Clo had journeyed too long and to too many distant lands with a thief really to be frightened of them.

Her father was not, Clo knew, of the knife-wielding brand of thieves. He did not crouch in the shadows and take poor travelers unawares. He did not threaten violence, frighten the innocent, terrorize the populace. He took only from those who had much… and most never noticed their loss.

Who would miss a pocket’s worth of pastries? A sausage link from the smokehouse? A sack of grain from the storerooms? Who would begrudge a father and his daughter a meal? Even a half dozen meals?

Who would notice the loss of an obsolete almanac or a well-thumbed primer? A chronicle left collecting dust? Who would berate a father for wanting to give his child some schooling?

Who would mind that he led away the oldest or lamest or stubbornest ass in the barns? No one would be sad to see those querulous beasts gone.

Of course, that wasn’t all…

Clo frowned and touched the cloak-wrapped package she was carrying. His thievery was not always so trifling. He always took one. At least one. A canvas. Some painted thing he found. Some piece of art he could sell. He could not help himself.

Clo tried to push away her misgivings. His work otherwise was honest. True. Above suspicion. A humble cleaner with his brushes and pots, an unassuming servant who kept to himself in the corners.

She thought of how he would present himself at the manor house whenever they arrived in a new village. At your service, he’d announce, bowing as deep as his crooked body would allow. Restorer of all decorative arts. He’d sweep his hat over the stones. Servile. Unassuming. For your lords and ladies, I can remove the dirt, the grime, the grease, the dust, the ash, the soot. I can erase cooksmoke and water stain, mildew spot and errant smudge; I can repair the yellowing of whites, the fading of pinks, the crackling of age. The smears along the ceiling frescoes, the tarnish on the gilded platters, the graying hues of family portraits—all can be made fair and bright and new.

Yes, honest night work, Clo thought, feeling the cloaked package in the dark again. Mostly honest, careful, modest work by candlelight. While the masters and servants of the house slept, he’d remove the grime that collected over years and years by wiping bread or potatoes across the painted surfaces, gently, painstakingly cleaning every detail. Or sometimes he’d mix a bit of color—steeping the woad leaves and madder roots that she grew for him in her garden or grinding a bit of lime or charcoal—and dab where paint had flaked away. “Honest night work,” she said quietly into the dark. Honest gardening. She was proud of the plants she grew.

They were not really thieves.

All about her, the woods were silent. The path opened in gray space ahead of her.

The harbor.

She hurried on.

Clo worried she might grow tired, but the farther she walked, the farther she seemed from sleep. Her sack and her father’s parcel both were hooked over her shoulder, and with each step, they shushed against her in a rhythm that said always, always, always. The always carried her deeper and deeper into the woods: it was just that sound, and her steps, and the grayness.

An hour passed, then another, and another. Her mind rested in a way that it would not have had she stopped: she was walking because she was supposed to walk. She felt full of the quiet and the dark. Always, shushed the bags. The moon, fragments behind the branches, sank deeper in the trees.

Only when a faint gold light began to rise and give shape to the forest did Clo start to tire and begin to wonder whether she had in fact fallen asleep, whether she was now dreaming of walking rather than actually walking. But by then, something in the air had changed. The woods were heavy with dew and the scent of pine, but there was something else as well. Clo could almost taste it, almost feel it, a stickiness on her skin. She sniffed. Something like salt—Did salt smell?—was thick in the air. You’ll smell’t afore sightin’ it, the swineherd had said. Was this the smell of sea? The idea hurried Clo forward. Asea, asea, shushed the bags at her quick steps.

In the half-light, the woods were opening up. The spaces between the trees grew larger, the light between them now more pink than gray. Clo’s legs ached with weariness, but still she rushed forward, the thought of sea and the thought that she might find her father there propelling her on. Overhead, a great gray-and-white bird flitted in the treetops. It gave a shrill cry—to Clo, a sound like rusty metal—and was gone. Seaseasea, thumped the bags against her.

The woods gave way to nothingness—no, not nothingness, pale blue sky and pale blue water on and on and on. Water that has no edge. Clo stared. She could not see where water or sky ended; each simply seemed to become the other. When she finally lowered her gaze from the horizon, she saw she was on a ridge, high above a town. Little houses perched alongside the water, and boats floated near the shore. Small figures, men with buckets and nets, moved between the boats and the buildings in a steady, busy pattern.

Cautiously, Clo followed the cart path down to the village. Harbor, she murmured. Having always skulked in the shadows, she found it easy now to slip into the town’s darker spaces, just out of sight of the figures carrying salt-stinking buckets and barrels and sacks from the boats to the shore. If any of the men, men as thick and sturdy and opaque as the barrels they carried, saw her, they saw only a disheveled boy, dirty and burdened, no different than any of the guttersnipes and urchins who scrounged in the town.

Clo, disheveled guttersnipe, slunk to the water’s edge. From here, the water was not a pale, flat expanse, but dark green with ripples and flecks of foam. It curled up the rocks, broke, retreated, curled again. Kneeling, Clo placed her fingers in a little pool at her feet and then touched her fingers to her tongue: full of salt. She dropped her bags and sat, feeling exhaustion settle over her limbs.

The sound of the water, its steady roaring, surprised her. It seemed to echo the sound inside her head now that she had done what her father’s letter asked her to do. She had reached the sea, she had reached the harbor: What was she meant to do here?

Pulling her father’s cloak-wrapped parcel onto her lap, she tried to undo the knots again. But the wool, damp from the night of walking and the salty air, seemed even tighter. If only she had a knife. She ran her hands along the rocks where she sat until she felt a sharp edge: a white shard, like a crescent moon. She pressed it into the fabric below one of the knots, pulling, sawing. The fabric split and came away.

Clo felt a pang of regret for having cut her father’s cloak, but she reassured herself: it was only a small corner, part of the bottom edge. She could repair it for him later. She pushed aside the bundled fabric; it opened and opened. To something orange. Something rank. A wheel of cheese.

A wheel of cheese?

Clo pulled the gap wider and raised out of the cut folds an enormous golden round. Its rind was dark and mottled, almost marbled, and its pungent smell cut through even the briny air.

Clo put the cheese down carefully on the rock beside her and stared at it, frowning. It was not unusual for her father to sneak provisions from the kitchens or the storerooms, and they had carried such wheels with them on their journeys before. But why would he send her this? How long would she be alone? How far was she meant to travel? How much cheese could she, Clo, spindle-shanked guttersnipe, eat?

The cheese smelled like despair.

Hoping this could not be all her father had sent, Clo reached again into the folds. She found a small square wound all about with rags, as though it were bandaged.

With growing dread, she unwound the scraps of cloth.

No. She pulled the wrappings over the object again.

Had anyone seen?

She looked around. Satisfied that the barrel-men were concerned only with their barrels, she lifted the rags once more just enough to see the object beneath.

It was a painting. Of course it was a painting. Fruit. A cluster of grapes, their dark skin marked with silver bloom and water drops.

It was not, as far as her father’s usual thievery went, a terribly remarkable painting. Usually, he took pieces that were obvious in their value. Look, Clo, he’d say, his fingers hovering reverently over a newly pilfered prize. The brushwork. The use of color. Masterful. The value would be obvious enough that the painting fetched a good trade or a handful of coins when he was finally ready to sell it. Though these grapes were well painted, beautiful even, the painting seemed too small to earn much—it was scarcely larger than her hand.

But its frame…

Usually he only took the canvas.

And this frame…

Her stomach turned.

Clo had never seen what might be called a jewel; she had never known ruby or emerald or pearl beyond their names, but here, she was sure, decorating the flowers carved in the wood, were rubies and emeralds and pearls, deep red and green and silvery gems glinting even in the slanting morning light.

Don’t worry, Clo, her father always said to her when he unrolled his stolen canvases. They won’t even notice it’s gone. He would reassure her: It was hanging in a forgotten corner. It was tucked in the shadows. It was stowed alongside a nest of mice in a cupboard. Don’t worry; it won’t be missed at all.

But this… surely this would be noticed. Surely this was the swineherd’s jewels missing out of th’ lady’s chamber.

What was she meant to do with this? She looked back at the barrel-shaped men. Was she meant to sell it? To them? She felt ill. She rewrapped the rags around it.

One last object remained in the cloak. Reaching into the wool again, she felt a leather corner, a soft edge. “Oh… oh, no…,” she whispered. She knew what this was even without seeing it, and she withdrew it with trembling hands. Her father’s notebook.

This book was part of his very person: he never parted from it. And here it was, tucked beneath a wheel of reeking cheese.

No, my lambkin. She could almost hear her father’s voice in the leather. You mustn’t touch this.

No, my dove. No, no. This is not for you.

The simple leather book—the only thing her father had ever kept from her. She ran her hand over its cover, thinking again of the rage that had come when, once, as a small child, she had crept up behind her father with the book open on the table in front of him.

He had been drawing, or trying to draw. Clo, silent, hardly breathing, had watched him try to outline the profile of a woman. His gestures were awkward, hesitant; the drawing, too, was awkward, hesitant—more a lopsided collection of angles and corners than a woman. But Clo, a child, had been delighted.

She had reached over him to touch the lines of the sketch. Is that my mother?

Why she had asked this, she did not know. Even then, small as she was, she knew it was the wrong question.

He had snatched the book away.

Clo, confused, had asked again. Is that—

But white, red, trembling with a rage that seemed to overwhelm his small frame, her father had not answered.

This is all I ask of you, he had finally said. All I ask, Clo. This is not for you. I forbid it.

The depth of his fury—his widened eyes, his shaking voice—was enough that she never touched the book again.

Even now, feeling the book still forbidden, she held it gingerly in her fingertips.

This was all. A wheel of cheese. Her father’s notebook. And a stolen painting that was surely the reason her father had been crouchin’ in th’ pens.

Clo felt the earth tilt a little under her.

Hesitantly, she turned over the notebook. It was tied, as her father kept it, with a band of leather. A slip of paper had been tucked under the band. Clo, it read, and then, in smaller letters beneath, be brave.

She worked the paper out from under the leather and unfolded it. Heart sinking, she saw at once it was not a letter from her father. She saw nothing familiar or expected at all.

What was this? How could she even begin to understand this? Her head swam. She felt as though something were unspooling deep within her.

The writing was strange, stretched, not her father’s dense, neat script.

1/2 paffage only! was scrawled and underlined in the corner, next to a wavery signature, CMDRE Haros, and a thick gob of red wax with an imprint of an oar. Clo ran her thumb over the raised impression on the wax.

Haros? Haros? The words of her father’s ink-splattered letter came back to her: travel alone. Passage? Passage where? Or half paffage where? What, who was Haros? Where was her father sending her?

Clo felt something tighten on her shoulder. “Girly,” said a voice next to her ear.

Clo jumped. Startled, confused, she could only think that the sea must have grabbed her.

“Girly,” said the voice again. “Yer wit’ me.”