THIS ESSAY DISCUSSES some large questions in Hobbes’s political philosophy. My aim is to identify what, if anything, Hobbes thought to be the central problem, or problems, of politics and to link the answer to an account of why the state of nature is so intolerable, of how we may leave it, and whether the manner of our leaving is well explained by Hobbes. I then turn to the implications for Hobbes’s account of the rights and duties of the sovereign, and then to the contentious issue of the subject’s right, in extremis, to reject his sovereign and rebel. In the course of that discussion, I also consider Hobbes’s account of the nature of punishment and the question whether his two rather different accounts are not one too many. In answering these questions, I shall say something about Hobbes’s conception of the law of nature, his theory of political obligation, and the role (or lack of a role) of religious belief in his political system.1 I say a little about Hobbes’s account of liberty and link its oddities to the politics of his own day.

It would be otiose to say much about Hobbes’s career here; that has been done elsewhere. I will emphasize some features of his life only to frame the discussion of the central arguments of his political philosophy and the interpretative problems they present. Hobbes observed that fear and he were born twins into the world because his mother had gone into labor upon hearing the (false) rumor of the approach of the Spanish Armada in the spring of 1588. “His extraordinary Timorousness Mr Hobs doth very ingenuously confess and attributes it to the influence of his Mother’s Dread of the Spanish Invasion in 88, she being then with child of him,” says Aubrey.2 Hobbes made much of this, treating caution as one of the primary political virtues, arguing that anxiety was the main stimulus of religious belief, and thinking that religious belief gave fear a useful focus.3 We shall see below how important fear is in explaining the causes and character of the “war of all against all” in the state of nature, in motivating persons in the state of nature to contract with one another to set up an authority to “overawe them all” and make peace possible, and in persuading them to obey that authority once it has been established.

Hobbes’s education at his grammar school in Westport and at Oxford was a literary one; in Oxford it was literary and “philosophical” in a traditional and non-Hobbesian sense. His first employment as a tutor and confidential secretary in the Devonshire household made use of the skills of a man of a literary and historical education; those are what he taught his charge, the young earl of Devonshire, and Hobbes’s first published work was a translation of Thucydides’s History of the Peloponnesian War. The publication was, in part, a compliment to Hobbes’s employer. It was not the only possible choice for a man who translated Homer into passable English verse in his extreme old age and wrote his autobiography in Latin verse (and much of his philosophy in Latin prose), as he did when he celebrated the marvels of the Peak District.4 He might have chosen many other ways to compliment his employer; the choice of Thucydides was a meaningful one, and its meaning was plain enough: “Thucydides is one, who, though he never digress to read a lecture, moral or political, upon his own text, nor enter into men’s hearts further than the acts themselves evidently guide him; is yet accounted the most politic historiographer that ever writ.”5 As to the implications of Thucydides’s work, Hobbes stressed that as far as Thucydides’s opinions of forms of government were concerned, “it is manifest that he least of all liked the democracy.”6

Twentieth-century readers admire Athens more than seventeenth-century readers did, and today we admire Pericles’s famous Funeral Oration without reflecting on the fact that Alcibiades (who urged the Athenians into the disastrous Sicilian expedition, the overwhelming defeat of which cost Athens the war) exerted more influence over Athens than Pericles ever did. We try not to notice when Thucydides observes that, under Pericles, Athens was a democracy in name only and a monarchy in fact because of the authority that Pericles could exercise. Hobbes emphasizes what we flinch from.

And upon diverse occasions he noteth the emulation and contention of the demagogues for reputation and glory of wit; with their crossing of each other’s counsels, to the damage of the public; the inconsistency of resolutions caused by the diversity of ends and power of rhetoric in the orators; and the desperate actions undertaken upon the flattering advice of such as desired to attain, or to hold what they had attained, of authority and sway among the people.

Not that Thucydides was a friend to aristocracy either.

He praiseth the government of Athens when it was mixed of the few and the many; but more he commendeth it, both when Peisistratus reigned (saving that it was an usurped power), and when in the beginning of this war it was democratical in name, but in effect monarchical under Pericles.7

Hobbes took to heart Thucydides’s message that democracies collapse into factionalism and chaos as their search for freedom and glory ends in civil war and self-destruction. Hobbes’s first work was historical and so was the work of his last years. Behemoth is perhaps a strange example of its genre, inasmuch as it takes the form of a dialogue in which the two parties exchange hypotheses about the causes of the English Civil War. Nonetheless, it was historical in form and in purpose; it was intended to unravel the course of particular events and to draw a moral from them: “the principal and proper work of history being to instruct and enable men, by the knowledge of actions past, to bear themselves prudently in the present and providently towards the future.”8 Since this essay considers Hobbes’s science of politics, and Hobbes explicitly contrasted that science with a historically based prudence, it is worth keeping in mind the fact that Hobbes also wrote history.

One last aspect of Hobbes’s career worth mention is his connection with the law during his brief career as amanuensis to Francis Bacon, inductivist and lord chancellor, and in his later excursion into jurisprudence in the Dialogue between a Philosopher and a Student of the Common Law. I shall argue that Hobbes’s political philosophy is “absolutist” in a slightly curious sense, namely, that perhaps his greatest wish was to show that a political system had to settle the question “What is the law?” with a clear, unambiguous, and indisputable answer; that the way to achieve that was to secure universal agreement that only one source of law existed; and that whatever that source declared as law was law. The so-called Hobbesian problem of order was cast by Hobbes in a particular light: how to escape from a situation in which there were no clearly enunciated and scrupulously enforced rules of conduct into a situation in which a determinate, ultimate, omnicompetent authority laid down the law and enforced it. Any authority with that standing and intended to perform that task must be legally absolute, that is, unchallengeable in the name of any other legal authority.9

There were many problems in the way of establishing such an authority; one was the arrogance of the common lawyers who held that “the law is such a one as will have no sovereign beside him.” The greatest of the common lawyers of Hobbes’s day, Sir Edward Coke, held that the “High Court of Parliament” was the only authority able to change the common law by statute, but he fell under the same Hobbesian anathema. The High Court of Parliament, in Hobbes’s account of the matter, could change the law only to the extent that the sovereign empowered it to do so. Qua court, its authority was derivative. Other obstacles included the foolishness of those who believed that only a republican, or “free,” government could be legitimate, and who therefore complained that the laws of a monarchy limited their freedom and had no binding force. They had simply failed to understand that all law limited freedom. The liberty at which republics aimed “is not the Libertie of Particular men; but the Libertie of the Commonwealth,” that is, its independence as a sovereign state, and “whether a Common-wealth be Monarchicall, or Popular, the Freedome is still the same.”10 A greater obstacle still was the arrogance or madness of religious fanatics who believed that God had spoken to them in their dreams, licensing them to legislate for others according to their inspiration or absolving them from the decrees of the unrighteous. Hobbes’s view of unauthorized inspiration is well known: “To say that he hath spoken to him in a Dream, is no more than to say that he hath dreamt that God spake to him;”11 his skeptical criticism of dissenters and enthusiasts reflected his view that religion must be subordinate to law so that law would not be subordinated to the ambition of priests. For Hobbes, the dividing line between religion and private fantasy was to be drawn by the sovereign authority as a matter of “law not truth.” It was to establish one unequivocal source of law, not to demonstrate the truth of some particular religious creed, that Hobbes waged his campaign to undermine the credibility of the unofficial prophets.

The final feature of Hobbes’s life to be borne in mind was his acquaintance with the greatest scientific minds of the day. He quarreled with several of them and was on the losing side on several occasions.12 Nonetheless, he was as deeply conscious of living in the middle of an intellectual revolution as he was of living in a period of political and religious revolution. The bearing of this fact on this essay’s concerns is simple: Hobbes’s political philosophy was distinctive in its ambition to be a science of politics. Hobbes’s positive understanding of what this involved is a matter of controversy. Hobbes explained what a science of politics was by contrasting it with political prudence; the latter was practical wisdom, practiced in the light of the best advice that we can draw from a storehouse of historical examples. Thucydides was a model of political prudence as well as the source of instructive examples, but Hobbes proposed to improve on him. The Romans, Hobbes remarks, rightly distinguished between prudentia and sapientia; we call both wisdom, but we ought to follow the Romans and distinguish them: “As much Experience, is Prudence; so, is much Science, Sapience. For though we usually have but one word of Wisedome for them both; yet the Latines did always distinguish between Prudentia and Sapientia; ascribing the former to Experience, the later to Science.”13 Prudence is the knowledge of events and affairs that comes from wide experience and reflection and from recapitulating the experience and reflection of others as recorded in history. Prudence is essentially experiential; its method is historical—whether it is a matter of retrospective reflection upon our own experience or upon that of mankind in general—and its object is sound judgment in particular cases. The best evidence of prudence is continual good judgment. Prudence is a genuine form of knowledge, yet it is always knowledge of particulars; it is a knowledge of how things have worked out in the past and what has happened, not of how they must work out nor of what must happen. Generalizations based on such experience are always in danger of being falsified by a novel, unexpected event.14

Sapientia is based on science. Science is hypothetical, general, and infallible. Most commentators have found nothing very surprising about the thought that science deals in hypothetical generalizations. Modern analyses of causal laws (water boils at 100°C, say) as universal propositions of the form (x) Ax → Bx (“If anything is water, it boils at 100°C”) treat them as just that. Yet nobody has offered an entirely persuasive account of Hobbes’s view that science is infallible; modern accounts of causal laws emphasize their fallibility, finding their empirical content in their capacity for falsification.15 Hobbes’s account becomes no clearer with his insistence that the only science we possess is geometry. For our purposes, we may decently avoid controversy and suggest that Hobbes’s assimilation of geometry and politics is best understood by analogy with economic argument. Economic theory explains the conduct of a rational economic agent by laying out the optimal strategy for such an agent to pursue. It is normative as much as descriptive because its explanations of what actors do do are parasitic on its accounts of what for them is the thing to do.16 I shall use an analogy I have used before and try to place no more weight on it than I must. Hobbes’s science of politics is a form of blueprint making; it sets out a rational strategy for individuals placed in the dangerous and anxiety-ridden state of nature, individuals whose goal is assumed to be self-preservation and whose means of survival are minimal. Politics so understood is a normative discipline, and in this resembles modern economics.17 The blueprint sets out what rational individuals must do if they are to form a political society; it does not predict that they will do. Far from offering a disconfirmable prediction of what they will in fact do, Hobbes’s politics relies for its rhetorical power on the fact that men have so often failed to do what the blueprint dictates and have thus caused themselves appalling misery.

Political science sets out what men rationally must do. Its relationship to empirical accounts of human psychology, anthropological investigations of nonpolitical societies, political socialization, and a great deal else that the twentieth century embraces under the general heading of “political science” is thus complex. It plainly has some vulnerability to factual considerations. If mankind were empirically so constituted as inevitably to fail to follow Hobbes’s prescriptions, we should at least lose interest in them—as we should lose interest in a theory of pedestrian safety that enjoined us to rise vertically ten feet above onrushing traffic. Short of that, it is hard to set out general rules for adjusting Hobbes’s science to the facts or the facts to Hobbes’s science. To the extent that actual agents pursue the recommended strategy, whether knowingly or unknowingly, their behavior will be both explained and justified by the theory; and to the degree that the world matches the world posited in the theory, their actions will “infallibly” produce the results predicted. The practice of modern economics suggests that Hobbes was right to link geometry and politics. Hobbes’s account of the horrors of the state of nature has, in recent years, often been interpreted as a prisoner’s dilemma problem, and contemporary economics places the analysis of strategic interactions at the very heart of its concerns.18

Hobbes’s contemporary Sir James Harrington, the author of Oceana, began the tradition of accusing Hobbes of slighting the historical understanding of politics in favor of his own scientific understanding.19 It is surely true that Hobbes thought that the scientific understanding of politics was superior to a historical one, and in that sense, he preferred “modern” prudence to “ancient” prudence.20 But this is far from implying that he despised historical analysis. What he despised was the habit he saw in many of his contemporaries of flaunting their historical erudition not to advance their understanding of their own age’s dilemmas, but to show off their learning. This was particularly foolish because it amounted to retailing secondhand experience in preference to their own.

And even of those men themselves, that in the Councells of the Commonwealth, love to shew their reading of politiques and History, very few do it in their domestique affaires, where their particular interest is concerned; having Prudence enough for their private affaires; but in publique they study more the reputation of their owne wit, than the successes of anothers businesse.21

He also despised the habit of taking past political actors, beliefs, or systems as authoritative models in current conditions. That the Athenians had practiced democracy was their misfortune; that the citizens of ancient republics had thought their governments free and all others servile was their mistake. To follow them blindly was to repeat their errors and to refuse to learn from experience. Learning from experience was not to be despised, particularly since it reinforced the lessons Hobbes’s political science taught. If Hobbes had not thought so, he would hardly have wasted his time writing Behemoth. Nor, for that matter, could he have published De Cive ahead of the rest of his projected system, on the grounds that it was “grounded on its owne principles sufficiently knowne by experience.”22

There was much that science could not prove. It could tell us that no society without an ultimate and absolute legal authority possessed a sovereign and that it was to that degree not a state at all; but it could not demonstrate that a monarch would make a better sovereign than an assembly. Experience tells us it is highly probable that monarchy is the best form of government, but Hobbes did not think he had demonstrated this conclusion, and he may well have doubted that it could be demonstrated.23 Demonstration handles large structural features of political life and leaves experience to deal with particularities. The science of politics tells us that anything we can properly regard as a state must have a certain constitution; to learn what a prudent empirical implementation of that constitution is, we must turn to experience. It could tell us what laws are, but not what the laws of any particular country are.24 Hobbes cannot have thought that a feckless monarch would be better than an assembly of thoughtful and prudent senators, any more than he could have thought that science could tell us whether a given judge would take bribes or listen to a case carefully. Science tells us what law is. In the light of that, we can appreciate the qualities to look for in a judge, such as a willingness to subordinate his private judgment to the commands of the sovereign. It cannot tell us whether Francis Bacon, Lord Verulam and a noted bribe taker, was a wise choice for lord chancellor.

This leaves much of the methodological detail of Leviathan unresolved. In particular, it leaves unclear why Hobbes should have devoted so much of the first two books of Leviathan to an elaborate account of human beings considered as elaborate automata. The emphasis on a speculative physiological reduction of the most important emotional and intellectual qualities of human beings does not, on the face of it, add much to what Hobbes might have achieved by starting with persons in the state of nature and elucidating the dangerousness of their condition as a preliminary to offering the only secure way out of it.25 To the extent that this physiological and psychological speculation provides a foundation for later arguments, it is by leading us to think, in a broadly constructivist way, that were we in the position of God, first creating the world, then man, and then exploring the consequences of putting man in such a world, there would be only one rational route to self-preservation available to man. This captures Hobbes’s talk of the way we create the state by analogy with God’s creation of the entire natural world; it is, after all, the very first thing he tells us: “Nature (the Art by which God hath made and governed the World) is by the Art of Man, as in many other things, so in this also imitated, that it can make an Artificial Animal.”26 It also leaves a great deal untouched. In particular, it leaves untouched Hobbes’s own skepticism about our knowledge of just how God rules the world. Hobbes elsewhere stresses that we can never know what God’s perspective on his creation is. We might draw up a system that seems rationally compelling to us, but God’s free choice cannot be limited by what seems rationally compelling to us.

Perhaps the most famous single phrase in Hobbes’s entire oeuvre is his observation that life in the state of nature is “solitary, poore, nasty, brutish, and short.”27 The interest of Hobbes’s view emerges by contrast with the views of his predecessors and successors. Aristotle, whom Hobbes savaged throughout Leviathan, sometimes by misrepresenting him for the purpose, had claimed that “the polis is one of those things that exist by nature, and man is an animal made to live in a polis.”28 Hobbes’s break with the teleological perspective of Aristotle’s Politics made this claim not only false but also absurd. States exist by convention, and conventions are manifestly man-made, so states are self-evidently artificial and thus nonnatural. But Hobbes dissented from Aristotle on the substance of human nature, too, even though he cheated in his statement of the difference. Men, said Hobbes, were not political by nature as bees and cattle were; their association depended on an agreement to observe justice among men who disagreed about who ought to receive what, and thus they needed common standards of right and wrong to regulate their affairs.29 This was hardly a hit against Aristotle. He had claimed that bees and cattle were sociable or gregarious, but not political—for just the reason Hobbes cited against him.30 Bees and cattle simply congregated together, but men could live together only on the basis of agreed principles.

Still, the difference persists; Aristotle thought that there was some kind of natural attraction toward the good and toward life in society. Hobbes thinks that at best there is a common aversion to the summum malum (supreme evil), or death, and that we become “apt” for society only by being socialized into decent conduct. Almost equally important is Hobbes’s insistence on the natural equality of mankind. For Aristotle, the social order can—and when things go well, does—mirror a natural hierarchy in which the better sort of person is plainly distinguished from the less good: aristocrats from their inferiors, men from women, adults from children, free men from slaves, and Greeks from barbarians. Hobbes rejected this view of the world. Not only was it false, but it also violated two conditions of political peace: one, that we should reckon everyone our equal and demand no more from them than we allow them to demand from us; the other, that everyone should acknowledge the sovereign as uniquely the fount of honor.31 An aristocrat was anyone the sovereign declared to be an aristocrat, no more and no less.32 The pride of descent that aristocrats displayed was a threat to peace; it made them think they were entitled to demand political preferment, it made them touchy about their honor, and it provoked needless fights. Thinking of humanity as morally, politically, and intellectually on a level reinforced the view that the state rested on universal consent rather than on a tendency toward a natural hierarchy.

Hobbes’s successors held a variety of views about the state of nature, ranging from the view that there had never been a state of nature, so that considering what it was like and how we might have emerged from it was a waste of time, to Rousseau’s view in Discourse on the Origins of Inequality that it was a peaceful condition, prehuman in important respects, and perhaps a model for a kind of innocence that we might hope to recover in a social setting at the end of some very long process of change.33 I shall contrast Hobbes’s account of the state of nature with Locke’s and Rousseau’s accounts, and will, in passing, mention Robert Filmer’s patriarchalist theory of government as a contemporary, but diametrically opposite, view.

Hobbes writes of the “condition of mankind by nature” without anxiety about its historical accuracy. He is quite right. As he says, the heads of all governments live in a state of nature with respect to one another. The state of nature is simply the condition in which we are forced into contact with one another in the absence of a superior authority that can lay down and enforce rules to govern our behavior toward each other.34 Like many of his contemporaries, Hobbes thought that the Indians of North America were still living in the state of nature. More importantly, the inhabitants of Britain had been in that condition during the Civil War; so not only was the state of nature a historical fact, but relapse into it was also a standing danger. Indeed, the state of nature with which Hobbes is concerned is more nearly the condition of civilized people deprived of stable government than anything else. This can be seen by a simple thought experiment.

There are many societies that anthropologists call acephalous. They have no stable leadership; there is nothing resembling law or politics in their daily life. Such societies persist for long periods. They have no apparent tendency to self-destruction, although they are easily wrecked by contact with more advanced societies. Hobbes seems to suggest that their existence is impossible to explain. In the state of nature, he says, we are governed by no rules, recognize no authority, are therefore a threat to one another, and must fall into the state he describes as a war of all against all. But, we counter, if that were so, acephalous societies would self-destruct. It is easy to think of reasons why they might not. Hobbes plays down such possibilities by saying only that the concord of the American Indians “dependeth on naturall lust” and by going on to observe that they live in a “brutish manner.”35 The brutishness of their existence is, however, not the decisive point. The decisive question is whether they can—at least on a small scale—get by with the laws of nature alone. On the face of it, they can. Hobbes never suggests that we cannot know what rules we ought, both as a matter of prudence and as a matter of morality, to follow. The members of acephalous societies can understand the laws of nature.

For enforcement, the institutionalized practice of the blood feud may serve well enough. If you murder me, I cannot revenge myself, but my brother can do so on my behalf. In a small society, it is likely that the murderer would be immediately obvious; if he has killed me only because he is murderously inclined, he will not find allies to help him resist vengeance. The knowledge that he faces the vengeance of my family will, one may hope, act as a powerful deterrent when he contemplates murder, so the whole process of taking revenge need never start. For this to work, several things have to be true that will not be true in large and complicated societies. It is crucial that my death must be known at once to my family, on whom the burden of revenge falls, and the probable killer must be easily discovered and brought to justice. This is not true in larger societies: if I am traveling on business and am robbed three hundred miles away from home, I must depend on institutionalized police power for help or on my own unaided force. Many people have suggested that Hobbes’s state of nature is peopled with the men of the seventeenth century; properly understood, this may not be a defect in the theory. That is, the theory may be designed around the problem of sustaining and policing a large, prosperous society, in which most people are known well only to a few friends but want to transact business and hold intellectual converse with distant strangers.

What is Hobbes’s theory? We are to consider men in an ungoverned condition. They are rational, that is, able to calculate consequences; they are self-interested, at any rate in the sense that they ask what good to themselves will be produced by any given outcome; they are vulnerable to one another—you may be stronger than I, but when you are asleep, I can kill you as easily as you can kill me; they are essentially anxious.36 They are anxious because they have some grasp of cause and effect, understand the passage of time, and have a sense of their own mortality. It is these capacities that Rousseau, for instance, denies that we possess merely qua human animals, and in their absence, he claims, we would be like other animals, heedless of any but present danger. Hobbesian man is heedful of the future. This means that no present success in obtaining what he needs for survival can reassure him. I pick apples from the tree now, but know I shall be hungry in six hours; my obvious resource is to store the surplus apples somewhere safe. But the logic of anxiety is remorseless. Will the apples remain safe if I do not find some way of guarding them? I find myself in a terrible bind. To secure the future, I have to secure the resources for my future; but to secure them, I have to secure whatever I need to make them safe. And to secure it. . . . This is why Hobbes puts “for a generall inclination of all mankind, a perpetual and restless desire of Power after power, that ceaseth only in Death.”37

Such creatures encounter one another singularly ill equipped in the natural condition. Each appears to the other as a threat, and because each appears as a threat, each is a threat. This is not because of any moral defect in us. Hobbes wavers somewhat on the subject of original sin, but the miseries of the state of nature would afflict people who do not suffer from original sin but who do have the anxieties that Hobbes ascribes to us. Nor does our knowledge of the moral law, that is, of the laws of nature, make any difference. Each of us has the natural right and the natural duty to preserve himself. This right is an equal right. You have no greater right over anything than I have, and I have no greater right over anything than you have. In the absence of a secure system of law to protect us from each other, we all have a right to all things; that is, we have no obligation to defer to anyone else or yield to them. This equality of right is matched by a rough equality of capacity and, therefore, an equality of hope. It is this combination that brings us to grief.

Each of us is a potential threat to everyone else because each of us faces a world in which other people may cause us harm. The reasons for this are threefold. First, the state of nature is a state of scarcity. You and I may both want the same apple, and even if we do not, we both want to be sure of having enough to eat. This sets us at odds. This is the condition described by Hobbes as competition. However modest we may be in our wants, we face the fact that other people’s use of the world may deprive us of what we need. I may be happy to drink water rather than champagne, but if your anxiety about future water supplies has led you to sequester all the local water supply, I shall have to do something to extract from you enough water for my needs.

The second cause of trouble is fear or diffidence. The logic of fear is something with which humanity has become extremely familiar during the past fifty years. It is the logic of interaction between two persons or two societies that can each annihilate the other, and neither of which possesses second-strike capacity, that is, the ability to revenge itself on the other post mortem. Two nuclear powers that can each wipe out the other side’s nuclear forces if they strike first, and therefore cannot revenge themselves on the other side if they do not strike first, would be the post–World War II illustration of Hobbes’s theory. The point to notice is that the horrors of the situation do not hinge on either party’s wishing to attack the other. People in this situation are driven to attack one another by the logic of the situation, no matter what their motives. Thus, I look at you and know that you can kill me if you have to; I know that you must have asked the question whether you have to. Do you have to? The answer is not entirely clear, but a plausible reason is that you will have looked at me and have understood that I have every reason to be afraid of you because you might need to attack me. But if that is true, you do need to attack me, and if I know that about you, I can see that I must attack you. If I let you strike first, my loss is complete. So however little I incline to attack you, I have a strong incentive to do so. Or, as Hobbes puts it: “From this diffidence of one another, there is no way for any man to secure himselfe, so reasonable, as Anticipation.38

Both these first two reasons for conflict can be dealt with fairly easily. Competition can be dealt with by the achievement of prosperity; if I can be sure that my efforts to achieve subsistence will indeed secure my continued existence, I have no further reason to fight. It is sometimes suggested that Hobbes failed to understand that markets help overcome scarcity, but this is surely as false as the equally common view that Hobbes’s politics are only about maintaining markets. The obvious reading of Hobbes is that once mine and thine are defined and enforced, we shall successfully look after our own welfare: “Plenty dependeth (next to Gods favour) meerly on the labour and industry of men.”39 Similarly, once there is a system of police, fear makes for peace rather than conflict. I see that you have every reason not to attack me, so think you will not; you see that I have every reason not to attack you (because we are both threatened with the same sanctions by the sovereign) and think I will not; now we both know that neither of us has any incentive to attack, so we both have even less an incentive, and peace is established.

The third cause of conflict is not so easily dealt with. This is pride, or vainglory. Hobbes insists that a peculiarity of human desire is its indeterminacy. Not only do we constantly change our ideas about what we want; we are chronically unsure whether what we want is worth having. There is no tendency to gravitate toward the truly good, for our desires are the psychological outcrop of a physiological mechanism that is in constant flux. But one crude test of value is the envy of other men.40 This presents a worse problem than the other causes of conflict. “Vain Glory” is satiable only when we reach the top of the heap, and the criterion of success is universal envy; vainglory cannot be slaked by prosperity, and it creates a competition that security cannot defuse. There logically cannot be more than one top position; if that is what we seek, the conflict between ourselves and others is absolute. It is not surprising that Hobbes treats pride as the worst threat to peace and assails it both in aristocrats who take pride in their descent and in their social inferiors who strive for riches and social position. It is the one attitude that has to be suppressed rather than merely assuaged or diverted, and it is apt that Leviathan is the story of the genesis of the creature who was king over the children of pride.41

The combined pressure of competition, diffidence, and glory leads to the war of all against all and to a life that is poor, solitary, nasty, brutish, and short. To escape this condition, men must devise institutions that will enforce rules of conduct that ensure peace. To discover what those rules are is to discover the law of nature. We are so familiar with such an argument that we may fail to see how different its assumptions were from the political assumptions on which most of Hobbes’s contemporaries relied. Filmer, for instance, argued in his Patriarcha that men had never lived outside government; the Bible and secular history concurred in tracing political history to life in small, clanlike groups governed by the absolute authority of the father. The Roman patria potestas (the power of the head of the Roman family) was much like the authority of Old Testament fathers; it was a power of life and death, a power to sell one’s children into slavery. It was the proper model of political authority. Although few modern readers think much of Filmer’s history, there is something deeply engaging about his response to the assertion in state-of-nature theory that men are born free and equal: they are not. Many others of Hobbes’s contemporaries would have thought it simply needless to stray outside English history in looking for the foundations of government. The realm of England had a traditional structure: it was an organic community to be governed according to familiar principles by the king, the Lords Spiritual and Secular, and the Commons. Hobbes thought that it was essential to go behind these debates. The polity had to be founded on the laws of nature, not on habit or on local myth.

Hobbes’s account of the laws of nature is distinctive. “A LAW OF NATURE (lex naturalis,) is a Precept, or generall Rule, found out by Reason, by which a man is forbidden to do, that, which is destructive of his life, or taketh away the means of preserving the same; and to omit, that, by which he thinketh it may be best preserved.”42 Hobbes sees that their standing as laws is problematic; in both Leviathan and De cive, Hobbes insists that a law is the word of someone who by right bears command. The laws of nature, conceived as deliverances of reason, are thus not, in the usual sense, laws. Hobbes sees this; he calls them “theorems,” which they surely are. Laws, properly, are commands rather than theorems, and thus exist only when someone issues them as commands.

These dictates of Reason, men use to call by the name of Lawes, but improperly: for they are but Conclusions, or Theoremes concerning what conduceth to the conservation and defence of themselves; whereas Law, properly, is the word of him, that by right hath command over others. But yet if we consider the same Theoremes, as delivered in the word of God, that by right commandeth all things; then are they properly called Lawes.43

This approach contrasts in an interesting way with that of Locke. For Locke, the argument runs through the inferred wishes of God and could not be sustained otherwise. That is, in the Lockean state of nature, a man first comes to the view that he is sent into the world about God’s business as the creation of an omnipotent maker, and then concludes that such a maker requires him to preserve himself, and others as far as that is consistent with his own preservation.44 This is a process of ratiocination and is, to that extent, like the process Hobbes invokes; but it is not the same process.

Hobbes, then, claims that we can see that the rules we ought to follow lay down that we must preserve our lives, and that we have an absolute right to do whatever conduces to that end. What most conduces to it is to seek peace, and that is accordingly the first law, just as the statement that we have the right to do anything necessary for self-preservation is the fundamental right of nature. We can then infer that the way to achieve peace is to give up as much of our natural right as others will. It appears that we must renounce all our rights, except only the right to defend ourselves in extremis. It is to be noticed that Hobbes does not suggest that we shall generally have any psychological difficulty in seeking peace. Some people have bolder characters and perhaps a taste for violence; they will present a problem, since they will not be moved by the fear of death that moves most of us to desire peace.45 Most of us are not like them, but, in fact, wish to be protected against them. Hobbes’s account of the way we are forced into conflict explains the conflict not as the result of our wish to engage in aggression, but as the result of our wish to lead a quiet life.

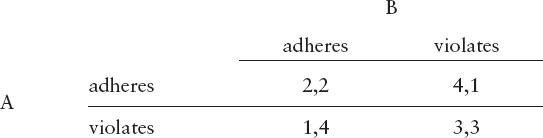

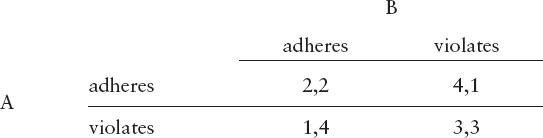

Moreover, we can see why it is a mistake to assimilate too closely Hobbes’s account of our situation to the prisoner’s dilemma of recent game-theoretical discussions. The prisoner’s dilemma is superficially very like the Hobbesian state of nature. The dilemma is that each of the two parties to the dilemma faces a situation in which, should he do the cooperative thing and the other person not, he suffers a great loss, whereas if they both do the noncooperative thing, they both do badly. A Hobbesian who, say, disarms himself without being sure others do so also may now be killed more easily by others; so he had better keep his weapons, even though everyone will be worse off if all are armed than they would be if all were disarmed. This looks very like the problem of a noncooperative, aggregatively inferior outcome dominating a cooperative, aggregatively superior one.

The matrix above does not put values on the outcomes, only on their ranking in the eyes of self-interested participants. Each participant ranks as his favored outcome the one in which the other party (party B) keeps his agreement and he (party A) benefits from that agreement while violating it. This occurs, for example, if the other person disarms himself and I take advantage of his unarmed condition to take what I want from him. Hobbesian man is supposed to repress this desire. This is why the state of nature is not a true prisoner’s dilemma. The essence of a prisoner’s dilemma is that because the parties to it are utility maximizers, opponents in the game will always try to exploit each other, and they know it. Hobbesian man will not. He is not a utility maximizer, but a disaster avoider. Your proper response to my disarming myself is to disarm yourself, not to kill me: to seek peace, not to maximize advantage. I do wish not to be vulnerable, not because I know you will exploit me if you can, but because I am not certain that you will not exploit me. In modern discussions, utility-maximizing assumptions ensure that none of the obvious ways of getting out of the dilemma will work. The most obvious is to agree to follow the cooperative route and to set up an enforcement system to enforce the agreement. But if we are utility maximizers, it will both be overstretched (because everyone will renege on their agreements when they can profit from doing so) and underoperated (because its personnel will not do their job as enforcers if they think they can do better by slacking off). In a manner of speaking, utility maximizers are rational fools, for they cannot but ignore agreements if it profits them to do so. Hobbesian man is obliged to keep his agreements unless it is intolerably dangerous to do so, and Hobbes does not suggest we will be tempted to stray, as long as we keep our eyes on the need to avoid the state of nature. Once Hobbesian men have agreed on the cooperative path, they will follow it not only until they can see some advantage in not doing so, but unless and until it threatens their lives.46 Hobbes relies heavily on his subjects’ fear of the return of the state of nature to motivate them to keep their covenant of obedience; as he says, fear is the motive to rely on, and he spent much of Leviathan trying to persuade them to keep their eyes on the object of that fear.

The explanation of this demands an account of the Hobbesian contract and its place in his political theory. Hobbes’s first two laws of nature tell us to seek peace and to be ready to give up as much of our right to all things as others are for the sake of peace. The third law of nature is “that men perform their covenants made.” This law is central to the entire edifice. It is also a slightly odd law. All the other laws, whether the basic injunction to seek peace or elaborate corollaries such as the requirement to give heralds safe conduct, are injunctions of a clearly moral kind. The requirement that we keep promises is peculiar because it seems to be both moral and logical. A covenant specifies now what we shall do in some future time; if it did not bind us (ceteris paribus), it would not be a covenant. Consider how often we try to evade a regretted obligation by saying something along the lines of “It wasn’t really a promise, only an expression of hope.” To know what a covenant is is to know that it is a way of incurring an obligation. This thought is what lies behind Hobbes’s claim that breach of covenant is like what logicians call absurdity, in effect saying that we shall and shall not do whatever it may be.47

The reason for Hobbes’s concern with covenants is obvious enough. If we are to escape from the state of nature, it can be only by laying aside our right to all things. That is, we can do that only by covenanting not to do in future what we had a right to do in the past—mainly by agreeing not to use and act on our private judgment of what conduces to our safety in contradiction of the sovereign’s public judgment, except in dire emergency. Hobbes sees that there are difficulties in the way of contracting out of war and into peace. Since we are obliged not to endanger our lives, we shall not keep covenants that threaten our safety, and a covenant to disarm would do that unless we could rely on everyone else keeping their covenant to disarm too. But how can we do that if there is as yet no power to make them keep their covenants? One of Hobbes’s more famous pronouncements was that “covenants, without the Sword, are but Words, and of no Strength to secure a man at all.”48 It seems that in order to establish a power that can make us all keep our covenants, we must covenant to set it up, but that the covenant to do so is impossible to make in the absence of the power it is supposed to establish. Hobbes, in fact, understood the problem he had posed himself.

He did not think that all covenants in the state of nature are rendered void by the absence of an enforcing power. The laws of nature bind us in foro interno (literally, “in the inner court”); they oblige us to intend to do what they require; a person who makes a contract is committed to carrying out his side of the agreement if the other party does and if it is safe to do so. If, upon making a contract, he finds that the other party has indeed performed and that it is safe to perform himself, then he is obliged in foro externo (publicly), too, that is, as to the carrying out of the act. It is no use pretending to recognize an obligation in foro interno but then failing to act when it is safe to do so. The only conclusive evidence of a sincere recognition of an obligation in foro interno is acting when it is safe. If I shout across the ravine that keeps us from injuring each other that I will place ten apples at some agreed-on spot if you agree to place five pears there when you pick up the apples, and I then place the apples there and retire to a safe distance while you collect them, you are obliged to leave the pears. If I can spare the apples and do not endanger my life by leaving them there, a Hobbesian, though not a twentieth-century game theorist, would think I did well to risk disappointment if you take my apples and leave no pears. Experimentally, of course, people behave as Hobbes suggests and try to create cooperative arrangements by engaging in tit for tat: if you take my apples and leave no pears, I “punish” you by not cooperating the next time; if you leave the agreed-on pears, I leave apples again.49

Can this explain the obligation to obey the sovereign and get out of the state of nature? Perhaps it can, even though most commentators have been sure it could not. Remember that not all of us are watching for an opportunity to take advantage of other people’s compliance with the laws of nature; we are watching only lest they take advantage of our compliance. It is, of course, absurd to imagine that we could literally make the sort of covenant that Hobbes describes as a “covenant of every man with every man, in such manner, as if every man should say to every man. . . .”50 It is far from absurd to imagine that we could, in effect, indicate to others that we proposed to accept such and such a person or body of persons as an authority until it was proved to be more dangerous to do so than to continue in the state of nature. In a manner of speaking, we do it the entire time inside existing political societies.

Hobbes was not apparently very anxious about such puzzles. Two reasons may be guessed at, although guessing is all it is. The first is that the usual situation in which we find ourselves is not that of setting up a state ab initio, but of deciding whether to swear allegiance to an existing government. That is, modern commentators are fascinated by the puzzle of how to create a sovereign by institution, but Hobbes paid more attention to the rights of and duties owed to a sovereign by acquisition. Hobbes published Leviathan when he came back to England and made his peace with the Commonwealth established by Cromwell after the deposition and execution of Charles I. He said that he thought the book had framed the minds of many gentlemen to a conscientious obedience, by which he meant that they had been moved by his arguments to understand that they could give allegiance to Cromwell without dishonoring their previous allegiance to Charles. So Hobbes’s topic was the “sovereign by acquisition” rather than the “sovereign by institution.” The second reason is that Hobbes’s most strikingly counterintuitive claim about the contract that binds us to the sovereign is that it is valid even if extorted by force.

Covenants entred into by fear, in the condition of meer Nature, are valid. For example, if I Covenant to pay a ransome, or service for my life, to an enemy; I am bound by it. For it is a Contract, wherein one receiveth the benefit of life; the other is to receive mony, or service for it; and consequently where no other Law (as in the condition, of meer Nature) forbiddeth the performance, the Covenant is valid.51

What Hobbes imagined was the situation in which we find ourselves, after the end of a war or the end of a decisive battle, at the absolute mercy of the victor. He is entitled to kill us if he wishes; we are in a state of nature with respect to him; we are, to use Hobbes’s terminology, an enemy. This does not mean someone actually engaged in fighting him, but someone who is not pledged not to fight him. The victor has the right of nature to do whatever seems good to him to secure himself, and killing us to be on the safe side is no injustice to us. In Hobbes’s unusual terminology, it cannot be unjust, since all injustice involves breach of contract and there is no contract to be breached. He may offer us our lives on the condition that we submit to his authority. Now we have a choice: to refuse to submit and so draw our death upon us, or to submit. What Hobbes insists is that if we submit, we are bound. To cite the fact that we submitted out of fear is useless because we always submit to authority out of fear: “In both cases they do it for fear: which is to be noted by them, that hold all such Covenants, as proceed from fear of death, or violence, voyd; which, if it were true, no man, in any kind of Commonwealth, could be obliged to Obedience.”52 The only thing that can void a contract is an event subsequent to the contract that makes it too dangerous to fulfill it. Nothing that we could take into account when we made the contract counts against its validity. Most readers find Hobbes’s view quite shocking, but it is, after all, true enough that when we go and buy food at a grocery, we regard ourselves as obliged to pay for what we purchase even though we are ultimately driven to eat by fear of starvation. Hobbes’s point was that both contracts—the contract of all with all, and the contract of the individual with the person who has his life within his power—are based on fear; and both are valid.

In some ways, the greater oddity of Hobbes’s work is the insistence that each of us is obliged only because each of us has, implicitly or explicitly, contracted to obey the sovereign. Of all the routes to obligation, contract is at once the most and the least attractive. It is the most attractive because the most conclusive argument for claiming that someone has an obligation of some kind is to show them that they imposed it on themselves by some sort of contract-like procedure. That route is uniquely attractive because promising is a paradigm of the way we voluntarily acquire obligations. It is unattractive for the same reason; few of us can recall having promised to obey our rulers for the very good reason that few of us have done so. American schoolchildren, who are obliged to pledge allegiance to the Stars and Stripes and “the republic for which it stands” most mornings of the school year, are an exception to this. It is odd that schools tend to drop this ceremony when children reach the age of reason and might be held to account for their promises.

The example of the pledge made by American schoolchildren shows one or two other problems. The most obvious is just what Hobbes tried to defuse with his claim that fear does not invalidate covenants. If we had approached a flag-burning dissident at the time of the Vietnam War and reminded him that he had once pledged allegiance, he would not have been much moved. For one thing, he might have said, he had had no option; if he had wanted to attend school, he had to say the pledge or face expulsion. How could a pledge extorted by such methods have any binding force? For another, students might plausibly complain that they had had no idea what was involved in pledging allegiance. How were they to know that the Republic for which the flag stood would subsequently turn out to be intent on sending them to get killed in Vietnam? Here, too, Hobbes’s response is that what we pledge is obedience to a person or body of persons, and in doing so we renounce any right to discuss the terms of that obedience thereafter. It is just because we renounce all our rights that Hobbes’s theory has the character it does. It is also what made it vulnerable to the complaints of Locke, who observed that it would be folly to defend ourselves from polecats by seeking the protection of lions; leaving the state of nature by exposing ourselves to the absolute, arbitrary power of the sovereign appears less than rational.

It seems odd that Hobbes should insist that obedience rests on a covenant, and that he should have so argued himself into a corner that he had to give a very counterintuitive account of the way in which coercion does and does not affect the validity of contract. One wonders what drove him to do so. Some aspects of his argument seem easily explicable; they were driven by the political needs of the day. It is part of his argument that when the person whom we acknowledge as sovereign can no longer protect us, we may look for a new ruler. The bearing of this on the situation of anyone who was formerly a loyal royalist and now had to consider whether to acknowledge Cromwell’s Commonwealth is obvious enough. To do this, though, he had to defuse the objection that a person who joined the service of a sovereign out of fear would feel himself permitted to leave it whenever things got hot. Hobbes denies this twice over. In the “Review and Conclusion” of Leviathan, he states:

To the Laws of Nature, declared in the 15. Chapter, I would have this added, That every man is bound by Nature, as much as in him lieth, to protect in Warre, the Authority, by which he is himself protected in time of Peace. For he that pretendeth a Right of Nature to preserve his owne body, cannot pretend a Right of Nature, to destroy him, by whose strength he is preserved: It is a manifest contradiction of himselfe.53

But he had earlier said clearly enough that what we do when we promise to recognize a given person or body of persons as sovereign is to sustain that authority in all necessary ways, particularly by paying our taxes willingly and by not quibbling over ideological issues.54

Less explicable is Hobbes’s insistence that obligation is self-incurred. Sometimes this insistence is diluted, as when Hobbes claims that by accepting our lives, property, and liberties from a sovereign who can lawfully kill us, we have in effect contracted to obey him. More commonly, it appears to have reflected a deep conviction that in the last resort, everything hinges on the thoughts and actions of individuals. Hobbes, we might say, saw himself as addressing his readers one by one, trying to persuade each of them to accept his case for obedience to an absolute sovereign. It is a vision that seems on its face not wholly consistent with his view that persons possessed of sufficient power can simply force others to subscribe to their authority. “The Kingdome of God is gotten by violence,” he observes; what that seems to mean is that because God’s power is irresistible, only he has unique authority not based on our contracting to obey him.55 But even then one wonders whether God’s dissimilarity to any human authority may not be the true point of Hobbes’s observation. At all events, Hobbes’s individualism is in the spirit both of the methodological tactics of the opening chapters of Leviathan and of the concentration on each individual’s fears for himself and his own concerns that underpins Hobbes’s account of the state of nature. And Hobbes’s individualism is important in his insistence that the limits of our obligation to obey the sovereign are set by our inability to give away our lives. We may say to him or them, “Kill me if I do not perform,” but not “If you try to kill me, I shall not resist.” It is one of the many peculiarities of Hobbes’s cast of mind that he insists that the rights of despotic sovereigns are just the same as those of sovereigns by institution, and yet still claims, “It is not therefore the Victory, that giveth the right of Dominion over the Vanquished, but his own Covenant. Nor is he obliged because he is Conquered; that is to say, beaten, and taken, or put to flight; but because he cometh in and submitteth to the Victor.”56

When the sovereign is instituted, or acquires his power by succession or conquest or some other conventional route, a strikingly lopsided situation arises. We the subjects have nothing but duties toward the sovereign, but he is not, in the strict sense, under any obligation to us. Hobbes’s argument for these alarming conclusions is a tour de force, but it has always struck critics as more bold than convincing. In the case of the sovereign by institution, Hobbes points out that we covenant with one another, not with the sovereign. Strictly, we are contractually obliged to one another to give up our natural rights in the sovereign’s favor. The sense in which we are obliged to the sovereign is somewhat tricky to elucidate. In one sense, he is the beneficiary of our contracts but not a party to them, as would be the case if you and I promised each other to look after a neighbor’s child. Are we obliged to the child as well as in respect of the child? Opinions vary. In Hobbes’s theory, it is a moot point, for the sovereign is the beneficiary of our promised intention to do whatever he tells us, which is just the position he would be in if our obligation was to him as well as to one another in respect of him. In any case, the central issue is Hobbes’s determination to show that the sovereign has no obligations to us.

Almost every commentator is so intrigued by this argument that it usually passes unnoticed that in the case of the sovereign by acquisition, the contract is made with the sovereign, who does therefore have—momentarily—an obligation to us. The step to be attended to is that the sovereign’s obligation can be instantly fulfilled. The sovereign in effect says to us, “If you submit, I will not kill you.” When he spares us, he has fulfilled his obligation. Our obligation, on the other hand, endures indefinitely. So the same situation comes about as comes about in the more complex case of sovereignty by institution: “In summe, the Rights and Consequences of both Paternall and Despoticall Dominion, are the very same with those of a Sovereign by Institution; and for the same reasons.”57

Nonetheless, the sovereign has duties. Indeed, he has obligations to God, although not to any earthly authority. For the natural law binds the sovereign, and as long as his or their subjects are more or less well behaved, this law binds the sovereign not only in conscience but also in action.

The Office of the Sovereign, (be it a Monarch, or an Assembly,) consiseth in the end, for which he was trusted with the Soveraign Power, namely the procuration of the safety of the people; to which he is obliged by the Law of Nature, and to render an account thereof to God, the Author of that Law, and to none but him. But by Safety here, is not meant a bare Preservation, but also all other Contentments of life, which every man by lawfull Industry, without danger, or hurt to the Common-wealth, shall acquire to himselfe.58

The inference is hard to shake: we are obliged to obey the laws of nature except when it is too dangerous to do so, and if the sovereign is moderately effective, it will not be dangerous for him to do so. No doubt a conversation might be imagined between Machiavelli and Hobbes on the question of what the sovereign should count as danger and how scrupulous he should be in following natural law.

For all that, Hobbes insists quite energetically both that there is no question of our holding the sovereign to account for anything he might do, and that he should be guided by the moral law. It is not too much to claim that Hobbes’s ideal sovereign would be absolute in principle, but indistinguishable from a constitutional sovereign in practice. Or, to put it otherwise, we cannot demand constitutional government as a matter of right, which is why Hobbes is never going to turn into a Lockean; but a ruler, when it is safe to do so, ought to govern in a constitutional fashion. This is, to belabor a point, a place where the coincidence of utilitarian and deontological considerations is very apparent. What other writers might demand as a matter of right, Hobbes derives from such obvious considerations as the fact that threats of punishment, say, will enhance the well-being of society only if people know what will happen to them under what conditions, and know how to avoid them. Retroactive punishment is thus contrary to the purpose of civil society, and so is to be deplored regardless of whether we have a right not to suffer it. Hobbes, in fact, comes close to letting a right not to be so punished back into his lexicon by a sort of conceptual sleight of hand.

Harme inflicted for a Fact done before there was a Law that forbad it, is not Punishment, but an act of Hostility: for before the Law, there is no transgression of the Law: But Punishment supposeth a fact judged to have been a transgression of the Law; therefore Harme inflicted before the Law made, is not Punishment, but an act of Hostility.59

The sovereign’s duties under the law of nature fall into three roughly distinct categories. On the one hand, there are restraints on his actions that stem from the nature of sovereignty, of which the most important are those that forbid the sovereign to divide or limit his sovereign authority. He can transfer it whole and undivided, set out rules for its transfer to his successor, and do whatever does not destroy it, but any action that seems to part with a vital element of sovereignty is void.60 The second class of actions embraces those things that the law of nature forbids or enjoins. A Hobbesian sovereign who observes these requirements will go a surprisingly long way toward recognizing everything that human-rights advocates demand of governments, except for one thing—conceding subjects a share in government as a matter of right. I shall return to that point almost at once, since it bears on Hobbes’s understanding of freedom. It is perhaps not surprising that the requirements of the law of nature coincide with the requirements of most human-rights theories; but it is worth noticing that those requirements forbid disproportionate punishments, forbid the ex post facto criminalization of conduct, forbid anyone to be a judge in his own case, and much else besides.

The final class of actions occupies most of Hobbes’s attention in the second book of Leviathan, in which he discusses what one might call the standard political tasks that a prudent and effective sovereign will have to perform. For the most part, they contain no surprises. We might wonder at the vanity that leads Hobbes to suggest that the sovereign would be well advised to have the doctrines of Leviathan taught to the entire population in order to keep their minds on the horrors of war and the blessings of order, but these chapters are in general not unpredictable in their concentration on the need for adequate taxation, security of property, and so on. They do contain two possible surprises for the modern reader. One is the prominent place Hobbes gives to the sovereign’s role in judging what doctrines may be publicly taught and defended. It is, says Hobbes, against the sovereign’s duty to give up the right of “appointing Teachers, and examining what doctrines are conformable, or contrary to the Defence, Peace, and Good of the people.”61 Hobbes’s views on religion were very complex, but two simple things can be said of them. The first is that Hobbes was so appalled by the way religion led men into civil strife that it was obvious to him that the secular powers had to control religious institutions and decide what might and might not be preached in the pulpit. Hobbes was in general an antipluralist, in the sense that his insistence on the sovereign’s unique standing as the source of all law meant that no subordinate body such as a church or university could claim any independent authority over its members, other than what the state might grant it. But what they could not claim as a right, they might well be given as a license to engage in harmless and possibly useful inquiry. As far as the church went, Hobbes was entirely opposed to ecclesiastical claims to the right to impose secular penalties. Hobbes anticipated Locke’s Letter on Toleration by arguing in his essay on heresy that a church should have no power over its members beyond that of separation from the common worship and, more contentiously, that the first secular laws against heresy were intended to apply only to pastors, not to the laity.62

The other thing one can say of Hobbes’s view was that he saw that the degree of religious uniformity the state needed to impose would vary with the temper of the people. If there was much doctrinal dispute, the state must settle at least the externals of behavior, such as whether altars were or were not to be used and whether we must pray bareheaded. These were conventional signs of honor, and it was a proper task of the state to set those conventions. Beyond that, Hobbes hoped that with the return of common sense, men might return to the condition of the early church and to “independency.”63 Too much intervention would be destructive of felicity.

The second surprise comes not at what Hobbes proposes to regulate in a way we might think excessive, but at what he proposes not to regulate. Hobbes was not a “capitalist” thinker, nor a theorist of commercial society; in many ways, he was hostile to the life of moneymaking and had a thoroughly uncapitalist preference for leisure over labor. Nonetheless, he advised the sovereign to concentrate on defining property rights, cheapening legal transactions by such devices as establishing registered titles to land—something not achieved for another two and three-quarter centuries—and encouraging prosperity by leaving his subjects to look after their own well-being. This was not a pure laissez-faire regime. Hobbes’s proposal was much nearer what we would call a welfare state, with provision for the sick, the elderly, the infirm, and the unemployed.64 Yet it shows once more how insistent Hobbes was that the central task of politics was to settle who had the ultimate legal authority and to make sure that the possessor of authority could get the law enforced. It did not follow that busybody legislation was prudent or useful. Indeed, once the matter was framed in such terms, it clearly was not.

All this is set out with no suggestion that the sovereign’s political self-control reflects the subject’s rights. Indeed, Hobbes is at pains to deny it. As we have seen, the subject, having given up his rights, cannot now appeal to them. Moreover, the one area in which Hobbes breaks entirely with later writers on human rights is his insistence that we have no right to have a share in the sovereign authority and that any system in which we try to set up a collective sovereign embracing many people will almost surely be a disaster. His grounds for so thinking are partly historical; that is, he believed that democracies characteristically collapsed into chaos and factionalism, and doubtless thought himself vindicated by the behavior of Parliament in his own day. Even more interesting, he broke with the tradition that held that one form of government, and one form only, pursued freedom. His view was summed up in a sentence from a passage we have quoted already: “There is written on the Turrets of the city of Luca in great characters at this day, the word LIBERTAS; yet no man can thence inferre, that a particular man has more Libertie, or Immunitie from the service of the Commonwealth there, than in Constantinople. Whether a Common-wealth be Monarchicall, or Popular, the Freedome is still the same.”65

Hobbes defines liberty in two not entirely consistent ways. First, in the state of nature, “by Liberty, is understood, according to the proper significance of the word, the absence of externall impediments.”66 Second, civil liberty, under government, is the absence of law or other sovereign commandment: “The Greatest Liberty of Subjects, dependeth on the Silence of the Law.”67 Both accounts make it entirely possible to act voluntarily only from fear, and neither suggests that freedom has anything to do with the freedom of the will. Hobbes disbelieved in free will and conducted a running battle with Bishop Bramhall on the contentious issue of freedom, necessity, and foreknowledge. His two chief purposes are clear enough. As we have seen already, he wanted to argue that a contract made out of fear for our lives is made freely enough to be a valid contract; the common view that coerced contracts are invalid ab initio he explained as a reflection of the fact that we are normally forbidden to force people into making contracts by the positive law of the sovereign. That civilized societies will forbid coerced contracts makes perfect sense. It is clear that there are sound reasons of policy for keeping force out of economic transactions.

The second great aim was to enforce the claim that freedom was not a matter of the form of government. In one sense, freedom and government are antithetical because we give up all our rights when we enter political society, except, as Hobbes observes in his discussion of the liberty of subjects, the right to defend ourselves against the immediate threat of death and injury. Had we reserved any rights upon submitting to a sovereign, we should have left open endless occasions for arguments over the question whether a given law does or does not violate one of those reserved rights. This would have frustrated the object of entering political society in the first place and so would have been absurd. Once we are members of political society, there is a further issue, which is the extent of the control our sovereign wishes to exercise over us. A despot who largely leaves us alone leaves us more liberty than a democracy in which the majority is constantly passing new legislation. This is the point of Hobbes’s reference to Constantinople. Being part of the sovereign does not add to one’s liberty; Hobbes is not Machiavelli, nor is he Rousseau. He felt strongly that the classical education of his day and religious enthusiasm could, in this area, combine to delude people into thinking that they could be free only in a republic: “And as to Rebellion in particular against Monarchy; one of the most frequent causes of it, is the Reading of the books of Policy, and Histories of the ancient Greeks, and Romans.”68

The thought that killing one’s king is not murder but tyrannicide is, says Hobbes, an encouragement to anarchy. To the degree that classical republicans talk sense at all, the freedom they have in mind must be the freedom of the republic as a whole from domination by outsiders. This plainly was a large part of what Machiavelli admired in the Romans, but hardly all of it. Here as elsewhere, Hobbes is not entirely scrupulous about painting his opponents in the colors that most flatter them.

Hobbes was not a liberal, and this statement goes beyond the observation that “liberal” is a term not employed in English politics until around 1812; Hobbes was strenuously opposed to many of the things that define liberalism as a political theory. Nonetheless, many things about his political theory would sustain a form of liberalism, and he held many of the attitudes typical of later defenders of liberalism. It is easy to feel that as long as nobody talked about their “rights,” a Hobbesian state would be indistinguishable from a liberal constitutional regime. The sovereign has excellent prudential reasons for listening to advisers, allowing much discussion, regulating the affairs of society by general rules rather than particular decrees, and so on indefinitely. Allied to the natural-law requirement to respect what we might call the subjects’ moral rights, something close to a liberal regime emerges.

Still, the antipathy to claims of right is a real breach with liberal political ideas. Whereas Locke insists that we enter political society only under the shadow of a natural law whose bonds are drawn tighter by the creation of government, Hobbes relegates that law to the realm of aspiration. If the sovereign breaches it, we are not to resist but to reflect that it is the sovereign whom God will call to account, not ourselves. It is an unlovely view, for it suggests all too unpleasantly that if Hobbesian subjects are told to kill the innocent or torture prisoners for information, they will do so without much hesitation. They may think it very nasty, but they cannot engage in conscientious resistance, or if they do, they must not incite others to resist with them. They may embrace martyrdom, but not engage in rebellion.

This is the aspect of Hobbes that many readers find repugnant. It cannot entirely be got round either. Still, we may in conclusion see whether even in this area there is something to be said for Hobbes’s views. We may approach an answer by way of Hobbes’s account of punishment. Hobbes has two accounts of punishment; they serve much the same purpose, but they are very different. The purpose they serve is to insist both that there is a real difference between legal punishment and the treatment of “enemies,” and that we are not obliged to submit to punishment without a struggle. The difference lies in whether the right to punish is a right the sovereign has gained upon the creation of the state or a right we all had in the state of nature that everyone but the sovereign has relinquished on submission. The first view would be an ancestor of Rousseau’s and Kant’s; the second view would be very like Locke’s were it not for the fact that Hobbes does not anticipate Locke in distinguishing the state-of-nature right to punish from the state-of-nature right to do whatever we need to defend ourselves from our enemies.

The first view follows from Hobbes’s discussion in chapter 30 of the nature of the obligation to obey the sovereign. He says unequivocally that the obligation imposed by civil law rests on the prior natural duty to keep covenants:

Which naturall obligation if men know not, they cannot know the Right of any Law the Sovereign maketh. And for the Punishment, they take it but for an act of Hostility.69

The second is offered in chapter 28, where Hobbes insists that

to covenant to assist the Soveraign, in doing hurt to another, unlesse he that so covenanteth have a right to doe it himselfe, is not to give him a Right to Punish. It is manifest, therefore, that the Right which the Common-wealth (that is, he, or they that represent it) hath to Punish, is not grounded on any concession or Gift of the Subjects.70

In the state of nature, we all have the right to subdue, hurt, or kill anyone we think we need to in order to secure our own preservation; what the covenant does is commit us to helping the sovereign to employ that right. What then distinguishes punishment from hostility is the regular, predictable, lawful, and public nature of the harm so inflicted.

The reason why any of this matters is straightforward. On the one hand, Hobbes must mark a difference between our vulnerability to punishment if we enter political society and then violate the rules, and our vulnerability to being treated as an enemy if we remain in a state of nature with those who have entered political society. Unlike Rousseau, who suggested that we might remain in something like state-of-nature relations and still be treated decently, Hobbes insists that if we were to remain in this situation, we could be treated in any way the sovereign thought fit, ignoring his own insistence that the law of nature at least urged the recognition, in foro interno, of acting with no more than the barely necessary force. By signing up for political membership, we sign up to suffer no more than the penalties prescribed by law if we break the law at some future point. This supposes that punishment is something other than the ill-treatment properly applied to enemies for our own protection.