‘It seems like a dream, having a child.’

VICTORIA’S JOURNAL, 20 DECEMBER 1840

VICTORIA’S JOURNAL, 20 DECEMBER 1840

PREGNANCY AND CHILDBIRTH were the greatest risks taken by women in Victoria’s reign. In 1840, when Victoria had her first child in her bedroom at Buckingham Palace, five in every thousand births resulted in the death of the mother. Women quite literally took their lives in their hands when they entered the birthing chamber. Surviving one childbirth was no guarantee of surviving the next, and many women also suffered difficulties afterwards. Victoria was well aware of several mothers in her court circle who had post-partum health problems – in 1839, the year before Victoria and Albert married, she mentions four such aristocratic women in her diary. High rank was no protection against complications, and medical help for women undergoing pregnancy and labour was limited. There was no pain relief and very few procedures available to help if things went wrong.

The spectre of what had happened to ‘poor’ Princess Charlotte – daughter of George IV and wife of Prince Leopold – who had died at the age of twenty-one in 1817 after the delivery of a stillborn son still haunted the court. Though this had happened before Victoria herself was born, she knew of it and had discussed Charlotte’s tragic death with Lord Melbourne. Until the birth of Victoria’s first child, Princess Charlotte’s lying-in was the last time a senior British royal had given birth. It’s easy to see why the young Queen was apprehensive and why she referred to pregnancy in her diary as ‘an unhappy condition’. Every time Victoria announced she was with child the whole court was forced to contemplate what would happen if the Queen did not survive.

IN VICTORIAN TIMES, both mother and child faced grave risks, especially if there were complications at or after the birth. The household guru of the day, Isabella Beeton, was a prime example of this – her first two children died in infancy and she herself perished, aged just twenty-eight, after giving birth to her fourth child. On average, a Victorian woman would have eight pregnancies in her lifetime, resulting in five living children. In 1842, when it became common practice for doctors to clean their hands before examining new mothers, childbirth mortality dropped from 18 per cent to only 6 per cent.

Medical knowledge of pregnancy and childbirth at the time was still dangerously lacking. There was, for example, no understanding that either alcohol or drugs were a danger to the foetus, or that wearing a corset might have medical implications for pregnant women. If they survived pregnancy, women were sometimes subjected to blood-letting on the birthing bed – a particularly damaging practice as many of them had ongoing nutritional deficiencies, as no prenatal vitamins were available. Indeed, Victorian nutritional advice for mothers-to-be was laughable – women were told that what they ate might affect their child’s personality and so were counselled against ‘sour and salty’ foods, like pickles, in case this resulted in a baby with a bad disposition.

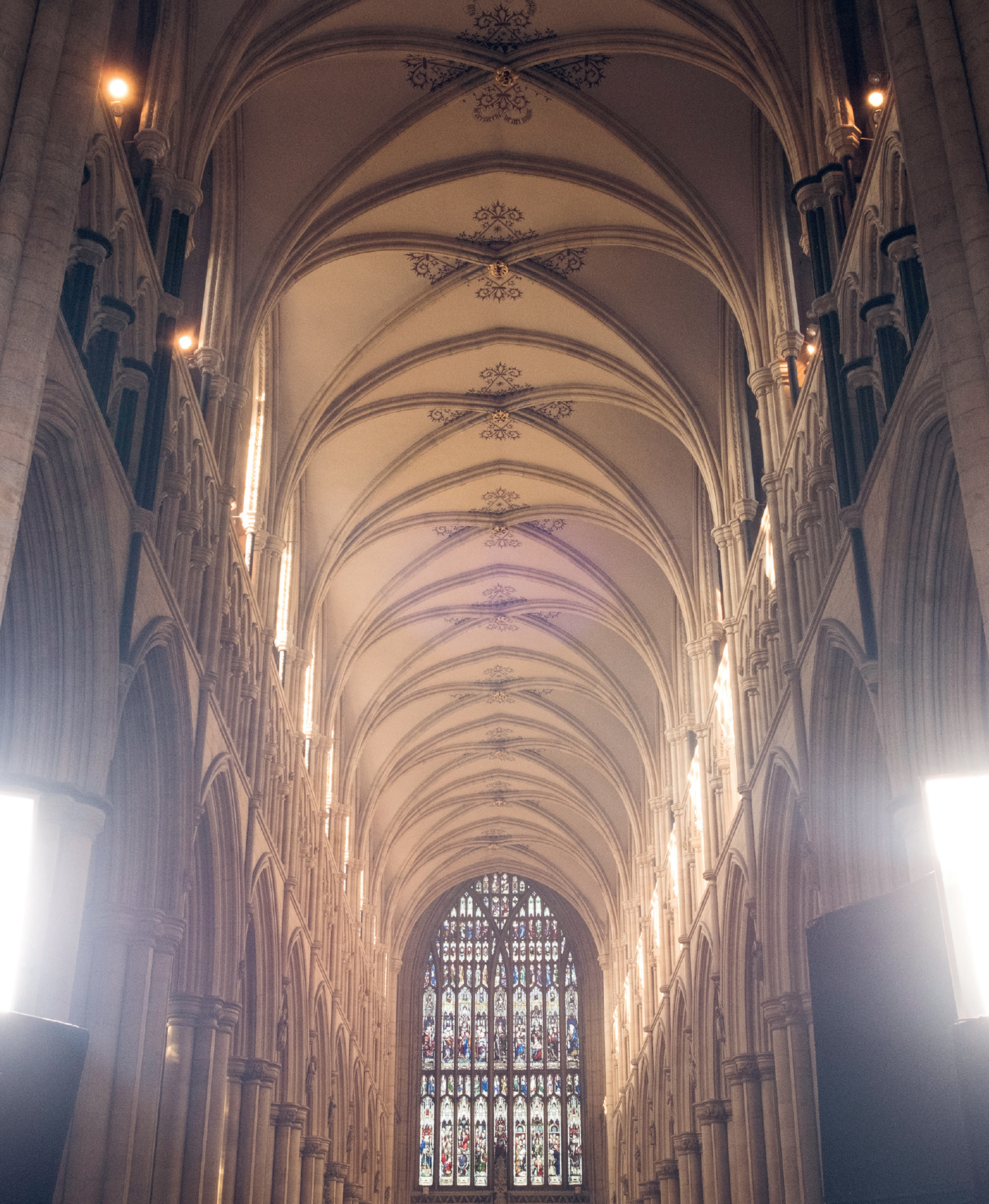

By the late 1840s the science of anaesthesia was beginning to revolutionise childbirth, offering women an escape from this so-called ‘punishment’. Victoria had wanted to try chloroform since she had first heard of it at the time of her sixth confinement, but her obstetrician, Charles Locock, had counselled against it. With Albert’s support, though, and the help of pioneering medical practitioner John Snow, the Queen availed herself of this new method at the birth of her eighth child in 1853. Incredibly, this was only possible by special permission from the Archbishop of Canterbury. Victoria inhaled the drug for fifty-three minutes from a handkerchief and was very happy with the results. She called it ‘that blessed chloroform’, said it was ‘delightful beyond measure’ and believed she recovered from the birth more quickly because of the pain relief. Her royal blessing ensured that many women then turned to chloroform to alleviate the pain of childbirth, and the Archbishop of Canterbury’s own daughter used it when she went into labour.

The recovery time for Victorian ladies after giving birth was commonly four to six weeks. Victoria refused to breastfeed her children and considered it the ‘ruin’ of intellectual and refined young ladies. But, in fact, breastfeeding provides the mother with a measure of contraceptive protection, so had Victoria breastfed she might have substantially reduced her chances of getting so swiftly pregnant again.

DUKE OF SAXE-COBURG:

Pity she is only a girl, but plenty of time, eh, Albert?

DESPITE THIS, VICTORIA seems to have enjoyed her early pregnancies more than those that came later, and initially her excitement at the prospect of having a child leaps off the pages of her journal. ‘How little I thought when I received him on the staircase that evening and beheld those eyes which seemed to go to my soul then, that I should not only be his wife but in the eighth month of my pregnancy on this same day, this year,’ she wrote in August 1840, clearly unable to believe how quickly she had gone from being a single woman to a wife and expectant mother – both paragons of what every woman should be, according to the society of the day. Her health was good – she didn’t complain in her diaries of morning sickness or other ailments associated with childbearing – she adored Albert and they were invested together in starting a family, so there was cause for optimism.

This does not mean that the Queen was not under pressure. Quite apart from the dangers associated with childbirth, Victoria was expected to produce a male heir to secure the line of succession. She admitted in her diary that she and Albert were ‘sadly disappointed’ when their first child was female, though after the birth she seemed quite bluff about the gender of her eldest and told Charles Locock, her obstetrician, that ‘next time it will be a boy’.

‘Dear Albert said he had never thought last year on this day, that his next birthday would be spent with his dear wife at his side and with the hopes of a coming child!’

VICTORIA’S JOURNAL, 26 AUGUST 1840

THE QUEEN LOVED the attention Albert showered on her during her early pregnancies – she found it romantic. Motherhood itself she found more contradictory. During pregnancy, Victoria was reluctant to allow doctors to examine her, and Eleanor Stanley, a maid of honour in Victoria’s service, describes medical men positioning themselves at the windows of the palace to watch the Queen getting into her carriage so they could guess how far gone she was. The truth was that medical knowledge was at such a primitive stage with regard to maternity care that though to the modern reader this seems cavalier on Victoria’s part, in fact there was little the doctors could do to either diagnose difficulties or avert them. The best action a pregnant woman could take at the time was to eat a healthy diet and maintain hygiene to prevent potential problems rather than cure them.

SIR ROBERT PEEL:

I am glad, Ma’am, to see you fully recovered. How fortunate you are to have such an able substitute.

ALBERT:

I try to be of service.

THE VICTORIAN ERA was filthy by modern standards. The well-known maxim ‘Cleanliness is next to Godliness’ was coined by the preacher John Wesley in 1778, but London had certainly not taken his words to heart. The upper classes generally bathed only a few times a month (and the lower classes even less frequently) and usually not at home. Instead, they headed to the Turkish baths that had become popular from the 1850s, particularly among upper-class men. By the end of Victoria’s reign over 600 Turkish baths had been built across the country. For women, costly bathhouses offered arsenic and lime washes to chemically burn off body hair if they did not want to shave, as the vogue for sleeveless evening gowns meant that upper-class women had to depilate.

Victoria herself was erratic in her personal hygiene and was told off on one occasion by Lord M for not having had a bath. Several visitors to court reported kissing the Queen’s jewel-bedecked hand and noticing that her nails were grimy.

Dentistry was also in its infancy. The French physician Pierre Fauchard, who died in 1761, is credited with being the father of the science; he pioneered fillings and braces and suggested swilling the mouth with urine to prevent cavities – which would, in fact, have been effective because urine has antiseptic properties. Even primitive dental implants were possible; the poor would sell their teeth to replenish the mouths of the upper classes (who had far poorer dental health because they had more access to sugar). The first toothbrush, however, was not patented until 1857, and as Victoria’s reign continued, despite advances in the science, it was still common even for the upper classes to have brown teeth and large gaps!

Head lice and bed bugs were also endemic. In the 1870s, a study suggested that 90 per cent of children had head lice, and these had to be picked out by hand. Victorian manuals suggest wiping sheets with kerosene to kill off bed bugs, while urine was commonly used by the working classes to disinfect clothes and blankets because soap was considered a luxury. For the middle classes, cleanliness became a social indicator and over time was even considered a moral duty, just as Wesley had suggested a century before. Household staff spent huge amounts of time keeping houses clean, as well as their employer’s family. The middle classes also instituted family bathtime, and as plumbed water and sewage became part of middle-class life, new products began to appear on the market. ‘Hair wash’ emerged from the 1830s onwards, based on recipes already in use in India, and in the 1850s the first commercial hair dyes became available.

‘What humiliation to the delicate feelings of a poor woman … especially with those nasty doctors.’

VICTORIA ON CHILDBIRTH, 27 JULY 1860

VICTORIA:

The birth was so distressing and nothing has become easier since.

WHILE VICTORIA AVOIDED medical attention, royal pregnancy and births were the subject of much ceremony and tradition, which had to be honoured. Eight of Victoria’s nine children were born at Buckingham Palace. Royal births traditionally took place in a very public fashion, with ministers, privy councillors, bishops and ladies-in-waiting all in attendance, because for many centuries there had been fears that royal babies might be swapped with ‘pretenders’ – babies from other families smuggled into the succession. Each royal birth was potentially the birth of a British monarch, so no chances were to be taken and it was therefore vital that lots of witnesses were present. Albert got rid of these bystanders although many royal office holders now simply attended the palace and waited outside the birthing room, rather than being present for the actual event itself.

Albert, however, broke with tradition. He protected Victoria by ensuring that staff did not talk about what was happening over the course of her pregnancy and he did not make the expected formal announcements about the progress of his wife’s condition. Many courtiers complained that they simply didn’t know what was going on. Albert also challenged tradition by attending the births of his children. Victoria’s first child, the Princess Royal, took twelve hours to appear and the Queen admitted that she ‘suffered severely’ at the birth. She later wrote that ‘there could be no kinder, wiser nor judicious nurse’ than Albert. He was clearly upset by her distress and sought pain relief on his wife’s behalf, but it would be more than a decade before Victoria was finally granted access to chloroform, to be administered as an anaesthetic.

Phrenology study – an 1840s craze that involved reading the skull for character. Phrenology study – an 1840s craze that involved reading the skull for character.

IN THE VICTORIAN era many drugs that are illegal today were commonly available, including cocaine, opium and marijuana, which were all used in household remedies, prescription and patent medicines. Women were often supplied with such drugs for ‘female complaints’ like menstrual cramps, pregnancy and neuralgia. One of the palace physicians, J. Russell Reynolds, was known to widely prescribe cannabis for various complaints, including period pain, and it is likely that he suggested the Queen try cannabis for this reason. Victoria hated the smell of tobacco smoke and banned the practice from her court, so if she did take cannabis it is most likely that she drank a tincture or tea made from the seeds.

There is also evidence that Victoria tried Vin Mariani. This was a Bordeaux wine or claret infused with coca leaves (from which cocaine is derived). It was a highly popular tonic and garnered testimonials from Jules Verne, Pope Leo XIII, the famous inventor Thomas Edison and the actress Sarah Bernhardt. Empress Elisabeth of Austria used cocaine for period pains.

As well as cocaine-based tonics, laudanum (or opium) was also widely available. The poet Elizabeth Barrett Browning used tincture of opium and had done from the age of fourteen. ‘The tranquilising power has been so wonderful,’ she wrote to her husband, Robert. She often said the drug helped her to be more productive. Sarah Bernhardt was also known to use laudanum to help her perform when she was ill.

As well as hard drugs, folk remedies and quack diagnostic techniques abounded, including phrenology – a craze that swept London in the 1840s that involved reading the skull for character traits and medical information. At least phrenology couldn’t actually cause any harm, unlike some of the Victorians’ wilder remedies. Medical dictionaries of the day, for example, suggest a mixture of warm, soapy water and gunpowder be ingested to cure stomach ache. Pipe ash was thought to cure wasp stings and hanging a dead mole around the neck of a teething baby was said to alleviate their toothache. Some remedies included actual poisons – Munyon’s Grippe Medicine, recommended for flu, was a combination of sugar and arsenic. One of the era’s less harmful remedies was Negus, a hot drink often taken at bedtime to help alleviate stress. It was made of port, sugar, lemon, nutmeg and hot water – and we know Victoria enjoyed it.

The Queen’s medicine chest is still on display at Osborne House to this day and thankfully does not contain any of the more dubious remedies on the market. Over the course of her reign there were huge advances in medical practice, but in the second series we see how some archaic practices were still very much in use, such as Lord Melbourne being bled with leeches. This treatment was only abandoned in the mid nineteenth century – a good decade into Victoria’s reign – and would not have helped Melbourne recover from the strokes he suffered latterly.

Killer diseases such as cholera, smallpox and tuberculosis were rife when Victoria took the throne, and though mortality rates slowly improved throughout the century, in the 1840s working-class men lived on average only into their twenties. Middle-class men fared a little better, with an average life expectancy of forty-five, but the fact was there was little doctors could do in the case of acute illness, and it wasn’t until well into the twentieth century that medical treatment truly became effective.

VICTORIA:

What does the Archbishop know about the pain and peril of childbirth! The ignominy of having to kneel in front of that old man as if I had committed some sin, instead of having a baby!

AFTER GIVING BIRTH the Queen was expected to spend several weeks recovering before attending a ‘churching’ ceremony to welcome her back into court life. Though she was the Head of the Church of England, Queen Victoria was not overtly religious. However, we do know that she prayed in private to thank God that she’d survived the births and that all her children were delivered safely. Ultimately, it was a cause of wonder among her subjects that Victoria produced nine children who all survived to adulthood – an almost unheard-of feat at a time when mothers commonly lost over 30 per cent of their children to disease in infancy. In 1839 it was estimated that half the funerals held in London were of children under ten years of age; being a child was even more dangerous than being a mother. Victoria’s children were lucky, though, and once safely delivered, they were handed straight over to a wet nurse for breastfeeding. These women were treated well – Princess Victoria’s wet nurse was paid £1,000 and given a pension of £300 a year (around £150,000 in today’s money).

Painted by Franz Xaver Winterhalter, this 1846 family portrait was purportedly one of Victoria’s favourite paintings of the prince.

THE CHURCHING CEREMONY was an ancient religious ceremony to bless a woman after childbirth that by Victorian times had been practised after royal births for centuries. Women were required to come to church decently dressed, which traditionally meant wearing a veil as a symbol of modesty. The service gave thanks for the mother’s safe delivery (even if the child was stillborn) and welcomed them back into the community. Churching marked the end of a woman’s ‘lying-in’ time, when she might be confined for a period after the birth to recover – often about forty days. For royal women and particularly for queens, giving birth was a duty to their family and to their country, and royal churching ceremonies reflected this. It’s not surprising that she found churching old-fashioned and resented the fact that it highlighted her function as a royal ‘milk cow’.

VICTORIA:

I should be pleased, I know, but it’s too soon. I feel like I am going back to prison.

INFORMATION ABOUT VICTORIA’S pregnancies is hampered by the fact that, after she died, the Queen’s diaries were heavily edited by her daughter, Beatrice, and it’s impossible to tell what details may have been removed. Still, in this early period, the diaries show no sign of Victoria’s later despairing and negative approach to pregnancy and childbirth. In fact, she declares herself quite charmed by the novelty of this new experience and was extraordinarily devoted to her firstborn, Princess Victoria, whom she often kept next to her throughout her working day. George Anson, Albert’s private secretary, noted that ‘the Queen interests herself less and less with politics … and … is a good deal occupied with the Princess Royal’. As the years went by, Victoria restricted her time with her children to two visits a day.

After the birth of her second child, Albert Edward, the Prince of Wales, Victoria did not write in her diary for several weeks. When she finally put pen to paper, almost a month after he was born, she expressed feelings of despair and misery, admitting that she had been ‘feeling rather weak and depressed’ and that she was ‘suffering so from lowness’. Many years later the Queen would write to her daughter, ‘I own it tried me sorely; one feels so pinned down … our sex is a most unenviable one.’ It is quite probable Victoria was suffering from postnatal depression. She was a woman who loved punctuality and order, and the nature of bearing children left her feeling alarmingly out of control.

‘When I think of a merry, happy, and free young girl … and look at the ailing aching state a young wife is generally doomed to … which you can’t deny is the penalty of marriage …’

~LETTER FROM VICTORIA TO HER DAUGHTER, PRINCESS VICTORIA, 16 MAY 1860

HARRIET, DUCHESS OF SUTHERLAND:

It is easier for a man. But for us — having a baby is a sacrifice as well as a blessing.

VICTORIA’S STATE OF mind wasn’t helped by the closeness of her first two confinements and also her physical size – the heir apparent, in particular, was a large baby and this put pressure on the Queen, who, at under five feet tall, would have found such a pregnancy extremely uncomfortable. Indeed, she later complained of just that, remembering the ‘aches … and sufferings and plagues …’ It is also likely that Victoria’s difficult relationship with her own mother meant she felt overwhelmed by the enormity of the task of motherhood and by her feelings of love for her children. The differing attitudes evidenced in the Queen’s journal and correspondence are consistent with bouts of postnatal depression, which severely altered her outlook on the difficult and dangerous business of bearing children from the birth of the Prince of Wales onwards. Reading what she wrote, it is easy to believe that, had contraception been available, Victoria would have stopped after her first two children. However, no such help was at hand.

Thus Victoria came to despise being pregnant and giving birth. She called these ‘female duties’ the ‘Schattenseite ’, or shadow side, of her marriage and often compared them to something animalistic or bestial, saying she felt ‘more like a rabbit or a guinea pig than anything else’. The issue of loss of control did not only refer to the physical side of childbearing; during her confinements Victoria also lost control of her royal duties. Albert was duly appointed Regent and took over from her during the more advanced stages of her pregnancies until well after the births themselves. A few months after the birth of the Prince of Wales in November 1841, Victoria’s spirits were so low that Albert arranged to take his wife to Scotland for a few weeks to give her a break (see here–here). The trip by sea and the subsequent holiday visiting Scottish nobles, particularly her new Mistress of the Robes, the Duchess of Buccleuch, who quickly became a firm friend, seems to have restored the young Queen, who came home to Buckingham Palace and shouldered her duties as a wife, mother and queen once more. However, after only a few weeks it was clear that she was pregnant again. While she continued to enjoy her children (particularly as they grew older – Victoria did not much like babies), she objected strongly to the trials of such frequent pregnancies.

‘I am really upset about it and it is spoiling my happiness; I have always hated the idea and I prayed to God night and day to be left free for at least six months, but my prayers have not been answered and I am really most unhappy.’

~LETTER FROM VICTORIA TO ALBERT’S STEPMOTHER, the dowager duchess of saxe-coburg and gotha

In essence, Victoria was caught between the traditional feminine role of wife and mother, and her public life as queen. Ultimately, though, her role as queen was more important to her sense of self than her role as a mother. As she continued to fall pregnant again and again, she felt frustrated at being ripped away from what she wanted to be doing. On a personal level, this was the same dilemma that meant Albert, as Victoria’s husband, was her ‘master’ but conversely also her ‘subject’. Victoria and Albert were not only man and woman, husband and wife, but also queen and consort. She was aware of this dilemma and commented in her diary that ‘good women … must dislike these masculine occupations’. And yet she was the Queen and as such was not comfortable giving up her royal role or power. It was deeply contradictory. The situation would probably have been intolerable if she hadn’t loved Albert so deeply and the bond between them had not been so strong. While Victoria had proved herself a competent political player more than able to reign, Albert had proved himself an excellent consort, who had his wife’s and children’s best interests, as well as the concerns of the country, at heart. There is some suggestion that he enjoyed Victoria’s confinements, as they gave him more power to make decisions, but Victoria and Albert were, above all, a formidable couple , more powerful together than they could hope to be separately.

ALBERT:

She has changed so much since the baby. It has made me so happy to be a father, but Victoria seems almost to resent being a mother.

‘This Duchess is fictional. Buccleauch is stuck in her ways – very proper, conscious of protocol and standards and she doesn’t like the Germans very much, which is very amusing because she’s surrounded by them. She’s very English and tells it as it is. She would appear to be very proper but there is a little twist in the story where she shows great understanding of a situation that you wouldn’t think she would understand.’

‘… an agreeable, sensible, clever little person.’

VICTORIA ON THE DUCHESS OF BUCCLEUCH

VICTORIA ON THE DUCHESS OF BUCCLEUCH

CHARLOTTE, DUCHESS OF Buccleuch, became Victoria’s Mistress of the Robes in 1841, taking over from Harriet, Duchess of Sutherland. The role of Mistress of the Robes was a political one – when a new government came to power, a new Mistress of the Robes was appointed – always chosen to be of the same political persuasion as the ruling party. Victoria had found this tradition difficult to accept in 1839 during the famed Bedchamber Crisis just after she came to power. She refused to dismiss her ladies and replace them with women chosen by the new Prime Minister. So when the government changed from Whig to Tory after Lord Melbourne’s resignation, Charlotte was appointed by Victoria on the recommendation of the new prime minister, Sir Robert Peel.

In the series, Charlotte is portrayed by actress Diana Rigg as a much older, curmudgeonly character. However, Victoria and the real Charlotte were contemporaries and there is no suggestion that the Duchess was anything other than light-hearted and supportive in her relationship with the Queen. Charlotte helped Victoria to prepare for her visit to Scotland in 1842 when Prince Albert took his young wife away for a holiday in a bid to lift her postnatal depression. The Duchess of Buccleuch and her husband met Victoria and Albert at Dalkeith during the trip, where the Duke and Duchess had built a church for the local community. With extensive property in Scotland, the Duchess also supported many Scottish charities.

When Charlotte resigned in 1846 because the Conservative government lost to the Whigs, the post returned to the Duchess of Sutherland. Charlotte, however, remained in correspondence with Victoria, and much later in the Queen’s reign the same post would be filled by Charlotte’s daughter-in-law, Lady Louisa Hamilton.

WOMEN’S FASHIONS IN the Victorian era are defined by one article of clothing – the corset. Corsets formed female bodies into what was considered the perfect silhouette, though the definition of this shape changed over time. Early in Victoria’s reign the ideal was considered a ‘cone’ shape, but by the 1850s the more traditional ‘hourglass’ had come into vogue. Corsets were originally made by skilled seamstresses, who constructed them from different pieces of material held together by lacing, adding whalebone strips to give support. A ‘busk’ or piece of wood (or sometimes metal) could be inserted down the centre front of the corset to give a smoother line. Later, the whalebone was replaced by steel strips, which were cheaper and more flexible.

Studies of Victorian women’s clothing preserved in museums have shown that women were on average smaller than they are today – in both height and girth. The young tended to wear their corsets tight, with older women allowing themselves more room to breathe! Most women only ‘tight-laced’ on formal occasions. Corsets came in a variety of shapes to accommodate different activities, including horse riding and pregnancy. While tiny waists were valued highly (Victoria had a twenty-two-inch waist on her Coronation Day), many corsets also had padding in the breast area to provide the ‘heaving’ bosom that was the natural corollary of the tiny waist.

With the advent of the sewing machine, the corset industry grew: production speeded up, turnover increased into millions of pounds and corsets became more effective and elaborate. Skirts widened and in the 1850s the ‘crinoline craze’ swept the nation, so it soon became impossible for a fashionable woman to get dressed without the assistance of a skilled lady’s maid. Later in Victoria’s reign the shape of skirts changed again and ‘bustles’ came into fashion. Towards the end of her reign, in the late 1870s, what’s known as the ‘Natural Form Era’ defined a more ‘natural’ silhouette shape as the ideal – though this was still corseted. High heels were also popular in this era to give the impression of a longer leg as the corsets inched lower, binding the upper hips as well as the torso. This style of bodice was known as the ‘cuirass’ because it felt like wearing an armour breastplate.