‘We all have our trials and vexations but if one’s home is happy, then the rest is comparatively nothing.’

LETTER FROM VICTORIA TO LEOPOLD, KING OF THE BELGIANS, 14 DECEMBER 1843

LETTER FROM VICTORIA TO LEOPOLD, KING OF THE BELGIANS, 14 DECEMBER 1843

IN THE CENSUS of 1841, Victoria, Albert and the Princess Royal are listed as living at Buckingham Palace along with a long string of staff, servants and courtiers. Victoria’s entry simply says ‘The Queen’, with no occupation stated. The palace had been in the royal family for generations by the time Victoria went to live there, having been developed into a royal residence by George III, and she and Albert were determined to make this sprawling 700-room palace into a modern home and to create as normal a family life as possible – both for them and for their children. To ensure the palace could accommodate their family plans they renovated it again to provide more nursery space, playrooms, schoolrooms and bedrooms through the addition of the East Front in 1847 – the newest of the four wings that surround the courtyard, forming the palace’s famous façade.

‘I wanted to put in as many staircases as possible because they make the dresses look really beautiful …’

MICHAEL HOWELLS, PRODUCTION DESIGNER

THE ROYAL FAMILY’s most famous palace began life as Buckingham House, a large townhouse built in 1703 for the Duke of Buckingham. The house was later developed by George III into a royal residence, and then George IV, who employed the foremost architect of his day, John Nash, to spend around half a million pounds on enlarging the building in the 1820s. The house still had its flaws, however. By the time George died in 1830, the house was still not furnished, and Nash did not relocate Buckingham House’s kitchen, which was built over a sewer and was therefore notoriously smelly. When George’s brother, William IV, came to the throne, he began to furnish the rooms, often using existing furnishings from other royal residences. In 1834, when the House of Commons burned down, King William offered Buckingham House as a new home for the country’s government, but it was turned down, and by the time Victoria came to the throne it had become the official London residence of the monarch.

Victoria and Albert part-funded their own remodelling of the house – by then known as Buckingham Palace. The central balcony from which our present royal family are often seen waving to well-wishers on the Mall was installed by Queen Victoria, who waved off and welcomed troops heading to the Crimean War from this vantage point. The royal couple bought furniture and accessories from the Great Exhibition at the Crystal Palace in 1851 and also reused fittings and china from the Brighton Pavilion, which was emptied when they sold it in 1845. The rebuilding undertaken by Victoria and Albert was the last substantial change to the layout of the by now 775-room palace.

Top: Façade of the East Front of Buckingham Palace, built during renovations in 1847 and part-funded by the royal couple. Middle: The Banqueting Room of the Royal Pavilion at Brighton, from which Victoria and Albert transferred fittings to Buckingham Palace.

11 December 1838

‘After dinner [I] told Lord Melbourne how Mama teased me about my drinking wine and told people I drank so much which schocked [sic] him much.’

VICTORIA’S JOURNAL, 11 DECEMBER 1838

ELIZA:

Sounds like an excuse for a party to me.

WHILE THE QUEEN and her family lived in luxury, surrounded by aristocrats and politicians, their family life was not far removed from that of their middle-class subjects. They loved to read, they wrote letters and sketched. The royal children, like their parents, delighted in new inventions like the bicycle and magic lantern and were diverted by piano recitals and theatrical presentations. They also attended church regularly and, among other outings, visited London’s parks and went out to shows and circuses. Within the confines of the palace, they played games and sports and all the children learned to ride. As well as these more private family pursuits, Victoria loved dancing and drinking and enjoyed parties. They were a family who loved occasions – no celebration went unmarked, from christenings and birthdays to Christmas and anniversaries – and state ceremonies were a normal part of royal family life. The Trooping of the Colour was, for the children, simply the normal way to celebrate their mother’s birthday.

VICTORIA WAS A woman of tremendous appetite. She loved to eat and drink and considered abstaining from alcohol ‘pernicious heresy’. She was not alone – Britain was a nation with an appetite for hard liquor.

If you were working class you probably drank either weak beer or gin. These were the only two alcoholic beverages cheap enough for poor people to afford and were certainly safer than drinking water for most of Victoria’s reign. As a result, beer was drunk all day and could be as weak as 2 per cent. Local pubs sprang up in working-class areas and many brewed their own beer and distilled their own gin, which was usually drunk at room temperature, neat or with a little sugar stirred in.

The upper classes had more choice when it came to alcoholic beverages. During the early part of Victoria’s reign, wine, champagne and brandy had to be bought in cases and were the preserve of the wealthy, though in the 1860s it became legal to buy a single bottle at a time. Mixed drinks were also popular, especially punch, which was regularly served at Buckingham Palace on special occasions. More fancy mixes like cocktails came to Britain directly from America. When Charles Dickens toured the US in 1842 he gleefully partook of Gin Slings, Mint Juleps, Sherry Cobblers and Sangree (Sangria). He wrote about the Sherry Cobbler in his 1843 novel Martin Chuzzlewit and smart Victorian society immediately adopted the cocktail – drinking it through a straw was considered highly glamorous. As ice became more widely available, the vogue for cocktails spread and by the end of Victoria’s reign upmarket cocktail bars began to appear in London, including the American Bar at the Savoy Hotel, which opened in the 1890s. A number of books containing cocktail recipes also sold well in the period, from which it can be deduced that the Victorian public liked to make cocktails at home, too.

Victoria’s favourite tipple, however, was whisky. William Fraser of the Brackla Distillery obtained a Royal Warrant from Victoria’s father, which Victoria renewed in 1838, shortly after coming to the throne. The Queen was not loyal to one particular distillery, however. In 1841, on the eve of the Prince of Wales’s christening, a member of the Royal Household wrote to Daniel Campbell of Islay to ask if he might ‘procure for the Queen’s cellar a cask of your best Islay Mountain Dew’. It must have gone down well. In a subsequent letter ‘another batch of the best Islay whisky for Her Majesty’s Establishment’ was ordered. Victoria was known to take whisky in her tea and also liked a glass of claret and whisky as a nightcap.

In 1848 the royal family took possession of Balmoral Castle, near the Lochnagar Distillery, and the owner, William Begg, who had sent a card of welcome to the Queen and her family, was delighted when Victoria, Prince Albert, two young princes and a princess turned up on his doorstep the next day. He eagerly showed them round and the Queen and Prince Albert tasted his wares, which then became a firm favourite not only at the family’s holiday home in the Highlands, but also at Buckingham Palace.

‘Bertie’s birthday table had been arranged by Albert, who is so really good & kind to the Children & so fond of them. Bertie got several toys, & a flag, in particular, caused him great joy.’

VICTORIA’S JOURNAL ON THE PRINCE OF WALES’S THIRD BIRTHDAY, 9 NOVEMBER 1844

BIRTHDAYS WERE ALWAYS a happy affair. Victoria notes in her journal on the Princess Royal’s third birthday: ‘We wished each other joy of our darling “Pussy’s” birthday, who is such a treasure to us, & we pray for her future preservation, to be a comfort to us all our lives!’ When the children were young, such celebrations were small family affairs with a few presents and perhaps a special nursery meal. Later, as they grew older, the celebrations became bigger. In 1846, when the Princess Royal was six years old, she was woken in her bedroom at Osborne House by a band playing under her window. The Princess joined her parents at her ‘birthday table’ and was presented with several pieces of jewellery and a writing box. That evening, Albert treated the whole family to a magic lantern show, and afterwards the Princess stayed up later than usual and had dinner with the adults. Victoria noted that the little girl stayed at the table till the end.

VICTORIA:

Shall we dance? After all, it won’t be long before my dancing days are over.

‘At the Service in the Chapel the Christmas Hymn was extremely well sung by our servants, accompanied by trumpets (“Posaunen”) & the Organ, which together have such a beautiful & festive effect.’

~VICTORIA’S JOURNAL, CHRISTMAS DAY 1845

THE ROYAL FAMILY generally spent Christmas at Windsor. Albert is popularly credited with bringing the tradition of the Christmas tree to Britain from Germany, but Victoria’s family was also German and Christmas trees had long been a British royal tradition. Victoria’s grandmother, Queen Charlotte, was known to bring yew trees inside as part of her yuletide celebrations

Traditionally, Victoria and Albert would decorate their tree together, tying on gingerbread and lighting candles before the children were brought in. It’s easy to paint a romantic scene with the young couple flirting as they chose where to place the ornaments. Albert also sent gifts of decorated trees to the local army barracks and the nearby school. There is an anecdote that tells of Lord Melbourne driving past at Christmas and catching a glimpse from his carriage of the royal couple lighting Christmas candles together, and then carrying on his journey alone. It’s unlikely to be true, but it certainly illustrates the fact that Albert had well and truly taken over the central space in Victoria’s life, which had previously been occupied by Lord M.

In reality it wasn’t only Lord Melbourne – the whole country was looking in on the royal couple, and when the Illustrated London News ran an engraving of the royal family around the Christmas tree in 1848 at the Queen’s Lodge in Windsor Castle, it was the first time most British people had encountered the idea of a whole tree being raised for Christmas, though it was common at the time for mistletoe or even branches of holly or yew to be brought inside. Christmas trees immediately became a sensation and soon almost every house had a fir bedecked with sweets and homemade decorations, the air scented with pine cones.

Creating a Victorian Christmas took production designer Michael Howells and his team months to perfect. ‘We knew we would have snow, even before we saw the script,’ he admits. The snow on set is in fact finely shredded paper – all of it biodegradable. For outdoor scenes, the ground had to be covered and then the ‘snow’ applied. Snow on trees required a different process. The team scouted for the location of the outdoor skating scene during one of the country’s hottest summers. Howells laughs, ‘It was a challenge to recreate the sub-zero temperatures. They built an ice rink and then dressed the snow scene around it. When one of the characters falls through the ice the team arranged a “tank stage” so the scene is shot in two different locations, which were later edited together.

‘Creating Christmas we relied heavily on the symbols we knew viewers would want to see. It’s all about tradition,’ Howells says. ‘We researched the way Christmas was – not like today at all – but very much about bringing plants inside – holly and ivy and spruce. All about the passing of the seasons. The result is beautiful – though a lot less glitzy than our modern Christmas.’ The team worked on two different briefs – the upstairs ‘German’ Christmas and the ‘English’ Christmas below stairs – and huge effort went into researching Victorian yuletide traditions so that everything from the garlanding to the Christmas toys shown on screen is authentic.

The Christmas tree was always going to be a focus. ‘It had to be spectacular,’ Howells says. ‘Christmas is a Pagan Festival, really, and we wanted to capture that. Though boughs of spruce or pine had been used inside royal residences since Queen Charlotte’s days, Albert was so important in establishing the decoration of the Christmas tree as a key part of the way most people celebrate, we focused on that.’ The decorations were made to order, including hand-made paper chains and 300 orange pomanders, studded with cloves. The team researched at the Toy Museum in Ilkley, where they rented original Victorian toys and also picked up ideas for designs. The resulting mixture of Jacks in the Box, rocking horses, castles, toy soldiers and toy theatres is absolutely authentic, many made by hand specifically for the episode.

Christmas dinner was also important, and on set the menu for the royal family featured beef, rather than turkey, as was more likely in the period. Though the upstairs shoot didn’t feature plum pudding, the team tried to find a way to include this traditional Christmas fare, if only below stairs. ‘We never know what will make the final cut,’ Howells says, ‘so everything has to be perfect. I don’t know if our plum pudding made it or not. We also had significant amounts of sugarwork to organise – cake was very important.’

Servants worked particularly hard during the festive season with the house full of guests so their Christmas celebrations took place towards the end of the season, sometimes as the decorations came down on Twelfth Night. ‘There would be a party for the servants. We wanted to show holly and particularly mistletoe – an opportunity for a stolen kiss,’ Howells says with a smile.

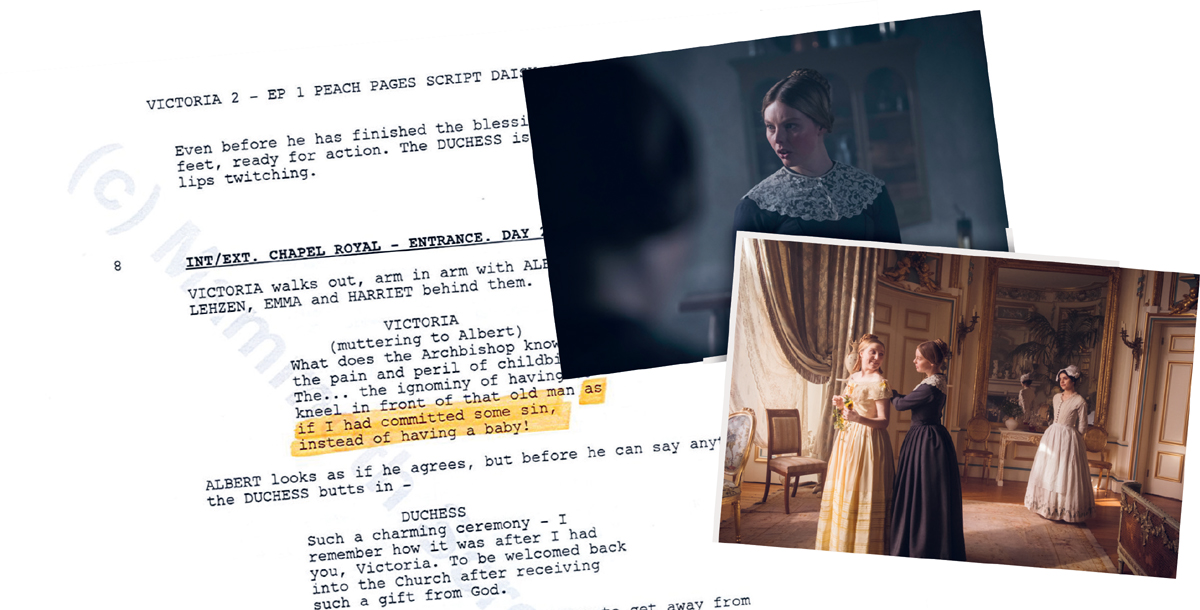

Scenes of the royal family at Christmas time.

THE ROYAL FAMILY thoroughly enjoyed Christmas. When Lady Bloomfield visited the royal nursery during the festive season in 1842, she reported that the Princess Royal was ‘in immense spirits … running in a state of childish excitement to show … two new frocks she had received from her grandmother … as a Christmas box’. The following year, in 1843, Charles Dickens published A Christmas Carol , now an enduring holiday classic, which immediately took the public by storm, with a hard-working family and a miser transformed by the Christmas spirit at its heart. In the same year Henry Cole commissioned the first Christmas card from John Callcott Horsley. This card cost a shilling – expensive for the time – but the idea quickly caught on and the royal children were encouraged to make their own cards, which they then sent to friends and family. The family also adopted the use of the newly invented Christmas cracker, or ‘cracker bonbons’ as they were known, which originally contained sweets.

A Victorian decorated Christmas tree, popularly credited to Albert as bringing the tradition to Britain from Germany.

SET IN THIRTEEN acres of grounds, Windsor Castle is the oldest occupied castle in the world. Victoria’s uncle, George IV, had undertaken remodelling work at Windsor, which came with a huge million-pound price tag. As Albert preferred the country, he enjoyed spending time there and getting out of London, where the air quality was not good and life was busier. Victoria, on the other hand, referred to Windsor Castle as ‘dull and tiresome’ and said it was like a prison, but she deferred to her husband and they used the castle during the visits of many dignitaries and on state occasions, as well as retreating there several times a year with the royal court.

The castle was not ideally suited to these state occasions, with visitors reporting that they were not always comfortable there – the rooms were small and difficult to heat. The kitchens were more efficient than those at Buckingham Palace, however, and during her reign Victoria made improvements to both the castle and its grounds, building a dairy to serve the castle kitchens and refurbishing the State Dining Room after a fire in the 1850s.

Both Victoria and Albert are buried in the Royal Mausoleum at Frogmore, just a mile or so from Windsor Castle.

Snowy scenes at Windsor Castle.

IN THESE EARLY years there were some famously cold winters during the royal family’s Christmas sojourn at Windsor and the lake at nearby Frogmore House often froze over, enabling them all to go ice skating. Another diversion was to take a ride in their red sleigh – one year they got as far as Slough in it, a trip totalling eight miles there and back. Back at the castle, the traditional royal meal wasn’t turkey, but rather an array of different meats that varied from year to year. On one occasion a roasted swan was the centrepiece. Another time there was a boar’s head. Typically, the royal family would tuck into around twenty different dishes on Christmas Day. The celebrations continued until 6 January, when a ‘Twelfth Cake’ was shared – a huge, ornately decorated fruitcake to round off the holiday season. Victoria and Albert’s family sensibility and commitment to celebration established the tradition of Christmas as a family holiday that endures to this day.

As well as giving each other gifts, Victoria and Albert were generous with their staff and courtiers. When Princess Beatrice edited her mother’s diaries she took out many of Victoria’s references to servants as she felt it was not fitting for a queen to take an interest in the lower orders. But Victoria in truth knew the names of all her personal servants and was known to be something of a soft touch, so determined was she to give the people around her the benefit of the doubt. She generously gave away gloves she had worn, as well as items of underwear and nightwear and dresses, to her servants.

Victoria and Albert enjoying a sleigh ride.

Before every read-through with the actors I make a little speech: ‘“Ma’am” to rhyme with “ham”, not “smarm”; “Buccleuch” rhymes with “taboo”, and “Afghanistan” rhymes with “barn”.’ Trying to get actors to pronounce words the nineteenth-century way is hard, particularly as we don’t always know how words were pronounced (audio recordings came late in Victoria’s reign), but when we do know we try to be as accurate as possible. A Victorian aristocrat would pronounce ‘either’ to rhyme with ‘fibre’, not ‘leaver’, and woe betide any actor who forgets this.

I have now got so used to writing in nineteenth-century-friendly language that I would never dream of having Victoria say, ‘That looks okay to me,’ as the word ‘okay’ only came into common usage in the twentieth century. But despite my best efforts, the odd anachronistic expression does get past my nineteenth-century filter. At one point a character talks about ‘falling pregnant’ – Victorian women certainly didn’t talk about being ‘pregnant’, which was a medical term; instead, they found themselves in an ‘interesting condition’.

When I am writing an episode I always have the Oxford English Dictionary to hand so that I can check when a word or phrase first came into use. It’s one of the challenges of writing Victoria to come up with language that sounds authentically nineteenth century, but not so convoluted that modern audiences find it off-putting.

The great pleasure of writing nineteenth-century dialogue is finding words and phrases that have fallen out of use: I love the gloriously self-explanatory ‘button hole factory’ as a euphemism for a brothel, and the word ‘transpontine’ to indicate someone from South of the River. The Victorian era was a time when educated people would all have known great swathes of poetry and the Bible by heart, so I can have my characters quote Shakespeare or the Old Testament with total credibility. Sir Robert Peel was an Evangelical Christian, so I have peppered his speeches with biblical sayings. And I used the Bible when I was trying to find a way for Wilhelmina to understand the relationship between Drummond and Lord Alfred. The word ‘homosexual’ didn’t exist in the 1840s, and well-brought-up young ladies would not have been aware that such a thing existed – unless, of course, they had consulted their Book of Samuel, where David’s feelings for Jonathan are described as ‘surpassing the love of women’.

In reality, Victoria and Albert would often have spoken to each other in German, but as I don’t speak German, I decided against making this a feature of the show. Occasionally, though, I have used untranslatable German words such as träumerei (literally ‘dream state’) to show how difficult it is for Albert to express himself in a language that is not his own. And of course his pet name for Victoria is liebes , which roughly translates as ‘dearest’ in English.

Getting the language right is exacting but so important. If a Victorian lady starts talking about getting in touch with her feelings, it’s the equivalent of wearing a crinoline with trainers. There is no point in filming by candlelight if the characters communicate in text speak. There are times when I would love for Victoria to say, ‘Laters,’ but I have to make do with, ‘You have my permission to withdraw.’

VICTORIA:

The newspapers are saying horrible things.

VICTORIA’S FAMILY LIFE is better recorded than that of any previous monarch – largely due to her collection of photographs, which runs to 20,000 items. The Queen placed such a high value on photographs of her family that before she died she instructed which particular images were to be buried with her. The huge collection includes pictures of royal family life, both posed and candid shots, that show an idyllic childhood of family pursuits. Victoria and Albert would often go through their photographic albums together in the evening. ‘It was such an amusement,’ Victoria wrote in her journal. ‘Such an interest.’ While sometimes these photographs can seem formal and give the impression that the family didn’t laugh or enjoy themselves, it’s important to remember that photographic processes of the day meant that the subjects had to stay still or the image would blur. Most photographs were taken in full sunlight, outside. On some occasions the Queen was not happy with the images, especially her own. ‘The day was splendid for it,’ she wrote of one session in her journal. ‘Mine was unfortunately horrid.’ She was known to scratch out her face on the negative or glass plate if she didn’t approve of the image.

Victoria and Albert chose to share some of these pictures with the public, making the royal family familiar to their subjects in an entirely new way. Certainly the family were watched eagerly and emulated in all things – even in their dress and accessories. When Queen Victoria wore a Sheffield tortoiseshell comb to the opera one evening, she practically revived the entire industry of British shellware. Similarly, new parents all over the country emulated the names the royal couple chose for the Princes and Princesses. The access the public had to Victoria and Albert was entirely new and it was a risk. Much pomp and ceremony surrounded being royal, and the royal family had up till then always been set apart from their subjects. By sharing even the most common family pastimes, Victoria and Albert succeeded in making themselves more human and easier to relate to, but they also opened themselves to scrutiny and invasion of privacy.

In 1849 the couple caused a scandal by going to court to block the publication of a volume of seventy-four etchings of their family life, which had been stolen by a journalist, Jasper Judge. Judge intended to have the etchings printed and put up for sale. For Victoria and Albert this was a step too far – the images Judge took were relaxed and very private. They show, among other things, the royal children playing with their pets. The book has personal annotations in Victoria’s own handwriting. The royal couple won their case in court and Judge was fined. On its return to royal hands, the book was given to George Anson, Albert’s personal secretary, and only became public over one hundred years later. This incident shows that the royal couple was in charge of their public persona and, while happy to share their family life to some extent, they understandably wanted to remain in control of what was released to the public and what was not.

THE ROYAL COUPLE had very different attitudes to food. Albert ate solely for fuel and did not relish the lavish spread of dishes that was prepared daily for the royal party’s delectation by Buckingham Palace’s forty-five kitchen staff. Worse, as far as many men at court were concerned, was that Albert refused to dally ‘with the chaps’ over port once the ladies had retired at the end of the meal. But he wasn’t really a drinker and was not interested in the kind of anecdotes that circulated once the ladies had left and the bottle was being passed from hand to hand – tales of soldiering, sport and infidelity. Many of the royal party were interrelated and had known each other since childhood, and Albert felt left out of their references to long-past incidents. He would leave the table after only five minutes and join the ladies, where he would sing duets with the Queen.

Victoria, on the other hand, relished mealtimes. She became upset if there wasn’t a sufficient spread of dishes and complained in her diary that it was a ‘miserable day – no pudding’. In her childhood, Victoria’s food had been rationed and the young Queen cut a slim figure as a result, but when she took over her own household that swiftly changed and she steadily put on weight. She also ate very quickly, cramming food into her mouth, and although she was aware that this was bad manners and tried to slow down, she didn’t succeed. As Queen, when she had finished what she was eating the plates were removed, so if you were at the table and did not eat as quickly, you would not get to finish your meal. And you certainly had to be fast to keep up – it was said that Victoria could polish off seven or eight courses in as little as half an hour.

Despite the Queen’s well-known love of sweets – she enjoyed all kinds of baked goods, especially tarts and cakes, and the wafer biscuits that her Uncle Leopold sent her from Brussels – she also liked savouries. She would pick up bones with her fingers and was very fond of mutton chops, eating them messily without using cutlery. On one occasion, a French visitor watched, open-mouthed, as she demolished three large platefuls of soup. Victoria also loved buttered toast – something a German newspaper had to explain to its readership, describing it as ‘slices of bread roasted on the coals and buttered hot’. The Queen ate vast quantities of it.

Victoria often preferred to breakfast privately in her room and then drank a glass of hot water at 10 a.m. to settle her digestion. She also loved to drink, and records show her particular fondness for wine and whisky. There’s no question that, unlike her husband, Victoria had a hearty appetite.

AFTER QUEEN VICTORIA’S chef, Charles Elmé Francatelli, left her service at Buckingham Palace on 31 March 1842, he went on to manage kitchens at both Crockford’s Club and the Reform Club. Francatelli was of a naturally liberal disposition and wanted to help improve the diet of ordinary people, while cooking for the upper crust. He wrote four cookery books, including The Modern Cook and A Plain Cookery Book for the Working Classes.

‘Her Majesty confesses to a great weakness for potatoes, which are cooked for her in every conceivable way.’

ANONYMOUS ACCOUNT OF VICTORIA’S FAVOURITE DISHES, 1901

FRANCATELLI:

There was a quart of cream in the pantry last night, for the syllabub tomorrow, all gone. And don’t tell me it’s rats, Mr Penge. Any more pilfering and I’m going to the Baroness.

THE HANDWRITTEN MENUS embellished with a St George’s cross at both Windsor Castle and Buckingham Palace reveal the royal family’s favourite foods, including dishes served especially to please Prince Albert (rice pudding – his particular favourite – is sometimes written on the menu in German). Albert was difficult to please at the table – he was more interested in doing things and considered eating a waste of time. Victoria, on the other hand, loved to eat and was known to ‘gobble’. She didn’t like to linger too long at the table and famously had a sweet tooth, enjoying:

… chocolate sponges, plain sponges, wafers of two or three different shapes, langues de chat, biscuits and drop cakes of all kinds, tablets, petit fours, princess and rice cakes, pralines, almond sweets, and a large variety of mixed sweets … Her Majesty is very fond of all kinds of pies, and a cranberry tart with cream is one of her favourite dishes.

~THE PRIVATE LIFE OF THE QUEEN , BY ONE OF HER MAJESTY’S SERVANTS, 1897

Victoria controlled the menus served in all the royal residences and ordered plain soups and roasts to be served in the nursery, though the children’s favourites (like Osborne Pudding – a bread and butter pudding made with brown bread and marmalade) also feature. However, the royal children were allowed and even encouraged to join the adults at mealtimes, dipping in and out of one of the most cosmopolitan dining tables in the world. It would be good preparation for their future lives as kings and queens of Europe.

Production designer Michael Howells’ team make sure that every prop on set looks perfect – from silk flowers to the huge gilded mirrors in Buckingham Palace – but nothing requires more attention to detail than the food that dresses Victoria’s special occasions, from christenings to the Plantagenet Ball to Christmas. One thing’s for sure: not everything is as it seems.

The platters of oysters served at the Plantagenet Ball were made out of lychees. ‘We need to accommodate actors’ allergies and their food preferences,’ Michael explains. ‘We work very hard on that.’ There are also modern-day laws to consider – it’s now illegal to eat the tiny birds that were actually served by the King of France when Victoria and Albert visited him in 1843, so Howells’ team had 200 tiny marzipan birds created, each one painted individually by hand to look like the real thing.

In many cases, however, the food on set is real. The glamorous ice sculpture of a swan that graced the Plantagenet Ball feast, for example, was in fact two ice sculptures, both made in Cardiff, driven to the set and then swapped around so that they would last the three and a half days of filming under hot studio lights required for the ball scenes. The biscuits, cakes and marzipan on display at the ball were all sourced from local people. ‘There are some phenomenal bakers up here in Yorkshire,’ Howells enthuses. He worked closely with local companies, referencing the original recipes of Victoria’s head chef, Charles Elmé Francatelli. Unlike in the first series of Victoria , in which Victoria and Albert’s huge wedding cake was mostly made of plastic, the cakes and puddings at the ball were real. Howells’ team also worked with taxidermists on the glorious display of poultry dishes, which included peacocks, swans and geese.