It’s hard to talk about this movie without talking about its director: Luchino Visconti was born into a noble Italian family, but he made his first big international splash with La Terra Trema, a chronicle of life in a Sicilian fishing village that was so authentically rendered that subtitles had to be added so that Italian audiences could understand what the amateur actors were saying. At the time, that naturalistic style was all the rage, but Visconti’s own personal style was always something a bit more . . . elegant. The Leopard, a historical epic chronicling the political turmoil of nineteenth-century Sicily, is saturated with color and moves fluidly from opulent scene to opulent scene—until the walls come crumbling down and a new, more democratic country is born. Through it all, the Prince of Salina, Don Fabrizio (played by Burt Lancaster) strides over this chaos with Bendicò (his loyal Great Dane) behind him. He is the perfect gentleman, and he is going down with the ship.

Jeeves is a man whose mother named him Jeeves; and, therefore, Jeeves is also, necessarily, a butler. Bertram “Bertie” Wooster, on the other hand, is not much of anything at all. He “is not” almost by profession. He is not employed. He is not unhappy. He is not especially intelligent. And he is not overly bothered by much of anything—except his overbearing aunts. But without Jeeves, Wooster would not be Wooster; and without Wooster, Jeeves would not be Jeeves. They are a master and servant, yes, but they are also a perfect pair. Bertie has the problems and Jeeves has the answers, over and over and over again. But the familiar setup operates in the same way that “the apartment” or “the coffee shop” operates in so many classic sitcoms: It simply allows us to settle in and pay attention to what really matters—namely, the interactions among the characters (and the inspired ways they denigrate each other).

It’s too bad that Evelyn Waugh was named Evelyn, because if he had simply been named “George” then “George Waugh” would be famous for having written one of the funniest and most truly enjoyable books in the English language, instead of being mocked for having a name that appears to have been stolen from an elderly English lady. But that’s just the way things go sometimes.

“Brideshead” is the estate of Lord Marchmain and his family—including, most notably, the young Sebastian Flyte and his teddy bear, Aloysius. (Note to Sebastian: If you are old enough to drink and troubled enough to brood over all of your many drinks, you are also probably too old to have a teddy bear, just as a general rule.) Sebastian’s difficulty in coping with his privileged existence is telling, however. This is one of the funniest books ever written, but it’s also deeply somber. The drunk scion’s teddy bear is a good indication of that tension. The family is old and rich and powerful, but they are also at the end of their rope. Luckily, ropes are much more interesting toward their ends, and the book’s narrator, Charles Ryder, is on hand to account for Flyte’s dissolution (via grain alcohol and whimsicality) and to give a full accounting of both what the family stood for and what they really were.

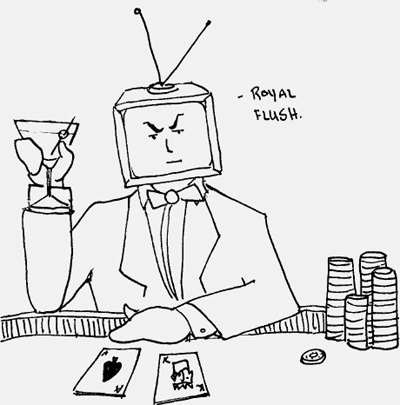

James Bond is not a member of the aristocracy in anything but the most metaphorical sense—but if anyone has ever had a stiffer upper lip than 007, I would like to meet this person, shake his hand, and offer to break the spell that has turned him into a statue. Ian Fleming didn’t waste any time in establishing the key elements in his first Bond novel. Casino Royale has it all: sangfroid, Russians, shaken martinis, expensive accoutrements, alluring strangers, dangerous new friends, sadistic villains, confusing plots, and torture. And on that note, if anyone ever invites you to strip down and make yourself comfortable on a chair that has no seat, DO NOT DO IT; but if you do sit down, and if someone does then cane you from below, take it like a spy. If you can get through that with style, then you truly have arrived.

It’s hard to imagine how Daniel Day-Lewis (the hyper-intense method actor), Martin Scorsese (the artiste behind America’s best gangster films), and Edith Wharton (the turn-of-the-century American author who obsessed over questions of decorum and social class) could ever find a common ground. Day-Lewis and Scorsese? That one’s easy: Gangs of New York. Wharton and Day-Lewis? Sure: They both share a genius for saying a lot with a little. Wharton and Scorsese, however . . . that’s where things begin to fall apart. But in an interview with Roger Ebert in 2005, Scorsese revealed the tie that binds them all together: “What has always stuck in my head is the brutality under the manners.” Sticks and stones may break my bones, in other words, but words may do the same. (And looks may do even worse.) If you want to learn how to stab someone to death with a pen (verbally, I mean) this is where you need to go to school.

Mr. Ripley is very talented at knowing what he wants and then pursuing it. According to many self-help books, this should make Mr. Ripley a very healthy, very wealthy, and very wise man, indeed. And by the end of the book, Mr. Ripley has in fact made himself far better off and far better situated than he was at the outset, but his greatest attribute is luck. His compulsion to take what he wants and be what he desires (and to do so without delay) makes him very prone to errors, but time and again a little stroke of luck stands between him and his always imminent (but never actual) punishment. The devil is in the details, however, and there are a lot of details in Mr. Ripley’s story. (Principle among them is the fact that he is not afraid to indulge in an occasional bout of murder.) From the selfishness to the cynicism to the strange blending of love and homicide, this is the story of a budding aristocrat, if ever there was one . . .

Russia has its counts and countesses, England has its dukes and duchesses, and we in America, what do we have? Well, high-powered trial attorneys for one, corporate kingpins for two, and media celebrities for three (and the win). Damages gives us all of the above. If you’re wondering what the American struggle for power looks like when it’s dressed up and ready for dinner, this is it. And if you want to know what the American struggle for power would look like after it has been shoved into an alley, handed a broom, and told to get ready for a knife fight, keep your eyes fixed on Rose Byrne in every single season premiere. Each new season plunks her down in a rat-infested bag of trouble, and the plot twists don’t let up until the finale, the cliffhanger upon which a new season will begin. Because this is America, where winning matters more than blood (and where blood only matters if it kills you). This is the rebirth of the aristocracy, all dressed up in red, white, and blue.

Once upon a time there was a thing called the aristocracy. It was a loose affiliation of nervous people who did what they could to “keep it in the family” so as to maintain their wealth and prestige. The aristocracy was not always loved, and people called it names, but it was feared and admired for a while (due to its success), before it was violently overthrown. Once upon a time there was also a television show called The Brady Brunch, which chronicled the conflicts and resolutions that occur when two distinct families (a father with three sons and a mother with three daughters) try to combine their respective parts in the California suburbs. This show was not always loved, and people called it names, but it was feared and admired for a while (due to its success), before it was violently overthrown. Then it was put into syndication and turned into a movie franchise, because duh.

Keeping Up with the Kardashians is the sum of these two ideas. The show is a fairly bald means of increasing the Kardashian family’s fame and prestige, but it’s also a sitcom, a reality show, and a place where reality seems to play no significant role. Most but not all of the children born to Kris Jenner (the matriarch) have names that begin with the letter K. Kourtney is the oldest, Kim is the famousest, Khloe is the most accented, and Rob is the K-lessest; but there’s also Brandon, Brody, Kendall, Kylie, and a rotating cast of American celebrities and superstars, from Reggie Bush to Kanye West to Lamar Odom. Some people love this family, other people hate it; but all in all, it has to be said that they are a pretty big deal. They are rich, attractive, famous, self-involved, and crass. They are who America wants to be. (But imitate them at your own peril.)

Season 1 of Downton Abbey was phenomenal because it was like being allowed to spend even more time on the grounds of Gosford Park (the setting of the film of the same name where Julian Fellowes first made his reputation). It was a place where rich people made decisions slowly, judged people rapidly, and fought against any and every possible change to the status quo—no matter how big or small. It was the entertainment equivalent of a rearguard action. But if Lady Grantham (played by Dame Maggie Smith) is playing defense for you, then hope is far from lost. For proof of this fact, see Season 2, in which Europe is ravaged by the First World War, influenza, and a variety of upstarts, but in which Downton also remains a stoical, implacable host to all. (And if you’re looking for proof of how sadistic an entertainer Fellowes really is, see Season 3.)

So with the possible exceptions of Keeping Up with the Kardashians and Casino Royale, all of the works mentioned above are really more about the death of the ruling class than they are about the existence of the same. They are all looking back at aristocracy. Thus, in order to find something that engages with the nobles on more or less equal terms, we have to move to a parallel universe: We have to move to the Seven Kingdoms, and play the Game of Thrones . . .

And in order to avoid losing ourselves in the murky political waters of this impressively epic TV series, let us just say that here, in this universe, might is almost always right. The only problem is that it’s often very hard to tell who is mighty and what exactly makes them so. The family that seems to have the firmest grasp on what it takes to achieve real dominance is the Lannisters. They are unquenchable in their thirst for power and merciless in their execution of it (no pun intended). There are many families who possess some share of political significance, or money, or dragons, but the Lannisters are the only real aristocrats in the show. (And how do we know this? Just listen to their accents!)

Like any number of great fables, Game of Thrones never strays very far from its central idea, but it is never held in thrall to that idea either. So to put it another way, Game of Thrones is about power in the same way that Peter Pan is about boyhood—that is to say, entirely and not at all. And although GOT is ostentatious where Peter Pan is wry, they both use the leash of their central theme as a means of keeping nearly everything relevant.

Game of Thrones takes place in a world where, like ours, anything is possible because everything is up for grabs—with sufficient means, that is. And thus, in a family that contains an uncompromising father, a charismatic son, a domineering daughter, a Joffre, and a dwarf, the Lannisters contain something for us all. Like the aristocracy, the only thing the Lannisters don’t contain within their ranks is the populace they trample underfoot. Oh, and dragons. (Which could be a problem . . .)