It’s kind of funny that we still use the phrase “the known world”—as though there were a portion of the earth that was still unknown. Spoiler alert: There is not. If you wanted to, you could open up Google Earth right now and plot a route from the Arctic North to South Africa using nothing but public transportation. But of course, it wasn’t always that way. Once upon a time, all you could be sure about, as a tourist, was that sooner or later you were going to enter the land of sea-monsters, upside-down humans, and mutant beasts. They were on the maps of the time not as decorations, but as real warnings. They were out there, somewhere. Also out there somewhere, circa AD 1271: Kublai Khan, the Mongol Empire, and very well-established boundaries between Europe and Asia.

These truly were the dark ages in Europe, but Marco Polo braved all of these dangers (real, imagined, and imagined but real) to try and find some light. He survived shipwrecks, thirst, hunger, and barbarous borderlands, and made his way into the court of Kublai Khan, where he thrived, personally and professionally, for over 15 years. He encountered much that was unusual there (including the use of sand as money and poison as remedy), and much that was familiar (including political ambition and courtly intrigue), but by putting his experiences into words, he managed to not just expand the known world, but also enliven and augment it. Before Marco Polo there was Europe on the one hand and Asia on the other; after Marco Polo, there was the wider world.

Back in the old days—back in 10,000 BC, for instance—you didn’t need to have money to be an explorer. So long as you were a strong swimmer and brave enough to set out on the water before anyone else did, you could very well find yourself on an island that no other human had ever seen before. (And then, once the island was discovered, you could plant your land stick in the earth and declare yourself President and Sole Resident of Mud Rock Sea Place.) But after we figured out how to construct a boat and calculate longitude, exploration became a rich-person’s game. Nowadays, whether you want to plumb the depths of the ocean or rocket into space, you need to have capital first. Luckily, Pixar has that. And even more luckily (luckily-ier?), they know what to do with it, once they have it. They know how to spend it, and where to go.

In Up, Pixar goes to the undiscovered country of the mind. Ed Asner plays Carl Frederickson, aka Ed Asner (the archetypal grumpy old man). And after a heaving sob-inducing opener, in which we see Carl go from wide-eyed kid to starry-eyed lover to married gent to bereaved widower in the blink of an eye, it seems as though the dreams of Carl’s youth are dead and gone forever. His wife is dead. They never traveled. He is about to get assistance with his living. But then he sets his house afloat (via balloons) and dares to see the world. Metaphor alert: The dreams of our youth and the uncharted territories of the map occupy the same territory. They are both the lands of unfulfilled potential.

If you’re an explorer and you’re not able to tell a good story, then you’re really not much of an explorer. “Oh, yeah, I borrowed a few boats and we headed west, and then we wound up in a stormy set of islands.” NO. “My name is Cristobal Colon. I fought desperately against the King and Queen of Spain in order to secure the ships I needed to challenge the very limits of the globe and discover what I now call ‘The New World.’” YES. That’s the ticket. Facts + flair = a future in exploration. And in that respect, Jacques Cousteau was the man with the golden ticket. A born entertainer and a lifelong wonderer, he wasn’t the most brilliant scientist ever, but he certainly made a real contribution to his field (by inventing SCUBA gear, among other things), and he never, ever, stopped selling his brand. When we watch nature programs today and marvel at the shots they get and the straightforward manner of explaining technical concepts, we are watching the legacy of Jacques Cousteau: the most French of all possible underwater explorers.

So yeah, TV’s pretty weird. It used to be the case that if humanity couldn’t see something with its own eyes, it pretty much didn’t exist. Then, around the nineteenth century, humanity started taking pictures and stopping time in its tracks. And then, in the twentieth century, the pictures started moving and talking, and Lucy loved Ricky, and Ricky loved Lucy, and you could watch sports at home, and then man was on the moon, and then we were there with him, and then . . . WHAT?! That is where we went too far. The war was cold, the medium was hot, and everyone was confused.

But no, it’s true: When Neil Armstrong, Buzz Aldrin, and the Apollo 11 crew landed on the moon, we were there with them. We were on the moon. We also, of course, remained on Planet Earth. That is a strange thing. For All Mankind tries to make a kind of sense of that strange thing, showing how these people got there, what they thought there, and what we saw when they stepped off a spaceship (a ship that flies through space!) there. On the moon. Where that weird man lives. (PS: How did he feel when humans stepped on his moon-face? Will we ever know?)

It’s hard to top the mysterious aura of outer space. Or at least it would be, were it not for Antarctica—a place where frozen ants reign over us all! No, just kidding, but it’s still pretty bizarre. Ice is everywhere; cold is everywhere; murderous, camouflaged predators are everywhere; and oh yeah, no, seriously, the cold will literally murder you all on its own. Nevertheless, Captain Ernest Shackleton thought it would be cool to hang out down there, and in August 1914, he set sail for the great white South aboard his soon-to-be infamous ship, The Endurance. But before he and his crew reached the Antarctic mainland, they were trapped in pack ice. Then the ship was crushed by the surrounding ice, and sunk. Then they had to figure out a way to get home before everyone froze to death, or starved to death, or was bored to death, or all of the above. Then Shackleton got everyone back home alive, where he realized he was broke. Then he decided he had to write a book, and South is what we wound up with. Fair trade? Who knows. Exploration, huzzah!

It’s no coincidence that so many classics from children’s literature and film take place in the animal kingdom. Animals are not human, so it’s magical when they act human; but it’s also deeply uncanny. And the closer we get to Homo sapiens on the evolutionary spectrum—and you can’t get much closer than the mountain gorillas that Dian Fossey studied—the more uncanny things become. (How uncanny, you ask? Answer: More uncanny than Fido’s guilty demeanor after his latest gas-blast.) Over her 13 years in the African jungle, Fossey was able to explore the prehuman world. She was able to see what friendship, love, fatherhood, motherhood, dinnertime, and war look like before a species has achieved a spoken language. And the answer is, it looks the same but very different. This is not a children’s book. Fossey navigated the worlds of two very different species simultaneously, and in the end, the world that she shows us is a new one: It’s not entirely human, and it’s not entirely animal, but it is entirely our own. (And she leaves it to us to decide who “we” are in this context.)

When it’s good, historical fiction is capable of two major benefits: It can either take a famous moment and offer an alternative or expanded account (as in Wolf Hall, for instance), or it can take an unexamined or obscure moment and attempt to shine a new light on it. Both options can yield thrilling results, and in The Long Ships, both options do. Swedish author Frans G. Bengtsson provides, on the one hand, an immersion into Viking life and culture (a topic of perennial interest and curiosity), and on the other, an illumination of the way European and Arabic cultures combined during the tenth century. Red Orm, the character at the center of this saga, is brave, hilarious, lucky, and, above all, Viking. But as you’ll discover, Red Orm has a very open (one could almost say “global”) notion of what it is to be a Viking, and what it means to be Red Orm . . .

From the very beginning, video games have always had an exploratory bent to them. Even when the screen rolled unrelentingly forward—in Super Mario Bros. for instance—there was always the chance that you could squat down on a pipe and pop into a netherworld (as one is wont to do when one is a Mario). But until video game technology really began to blow up in the late 1990s, you could only “explore” a video game in the way that you were able to “explore” a painting. In both cases, you were limited by what the artist wanted to show you. But then Ocarina of Time happened, and all of a sudden gamers all over the world were moseying along rolling hills, probing into dark corners, and moving on to the business of slaying enemies and saving the world when they well and truly felt like it. And as it turned out, the bumper stickers were right: a lot of people really would “rather be fishing.” Even virtually.

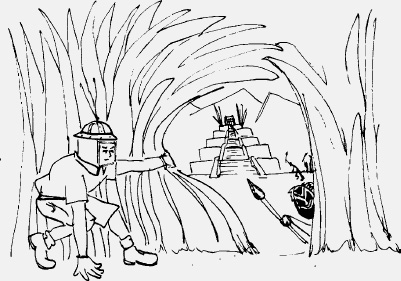

In 1527, any trip to the New World was a pretty intrepid act of exploration. The country was less than 50 years old to Europeans, and each trip required passing over what had previously seemed an infinite ocean, docking in a tumultuous harbor (usually in the storm-tossed Caribbean), and then trekking over strange new lands, peopled with strange new people. And that was what was on the menu if your trip went as expected. In Cabeza de Vaca’s case, the trip did not go as expected. First comes shipwreck; then comes hunger; then comes battle, slavery, escape, and a nearly unending trek across what we would now recognize as the southern United States. On every step of this incredible journey, from Cuba to Florida, Texas, Guadalajara, and Mexico City, de Vaca encounters an America that is pre-Spanish, pre-English, and pre-American. If ever there was a time-travel novel, this is it. It’s nonfiction as science-fiction, and it’s the craziest vacation ever.

It’s all well and good to fly to the moon, or dive to the bottom of the sea, or discover America, or be “first” to some place else, but let’s give credit where credit is due: namely, to the ducks of DuckTales—and, of course, to that king among ducks, Uncle Scrooge McDuck. These brave ducks do it all. In addition to traveling all over the animated world, they also pop into other centuries and other cultures at the drop of a hat. And in addition to fending off real-world dangers (like crooks, robbers, and thieves), they also readily confront imaginary perils from the world of pop culture (like harpies and the malevolent forces in Homer’s Odyssey . . . and the Beatles). It’s easy to get lost in such a post-modern landscape, but these ducks don’t care. To put it another way: They don’t give a flying duck. To rephrase: They don’t give a Launchpad McQuack. For all these reasons and more, they are the greatest explorers that the world (whether real and imagined) has ever known. DuckTales. Woo-ooh.